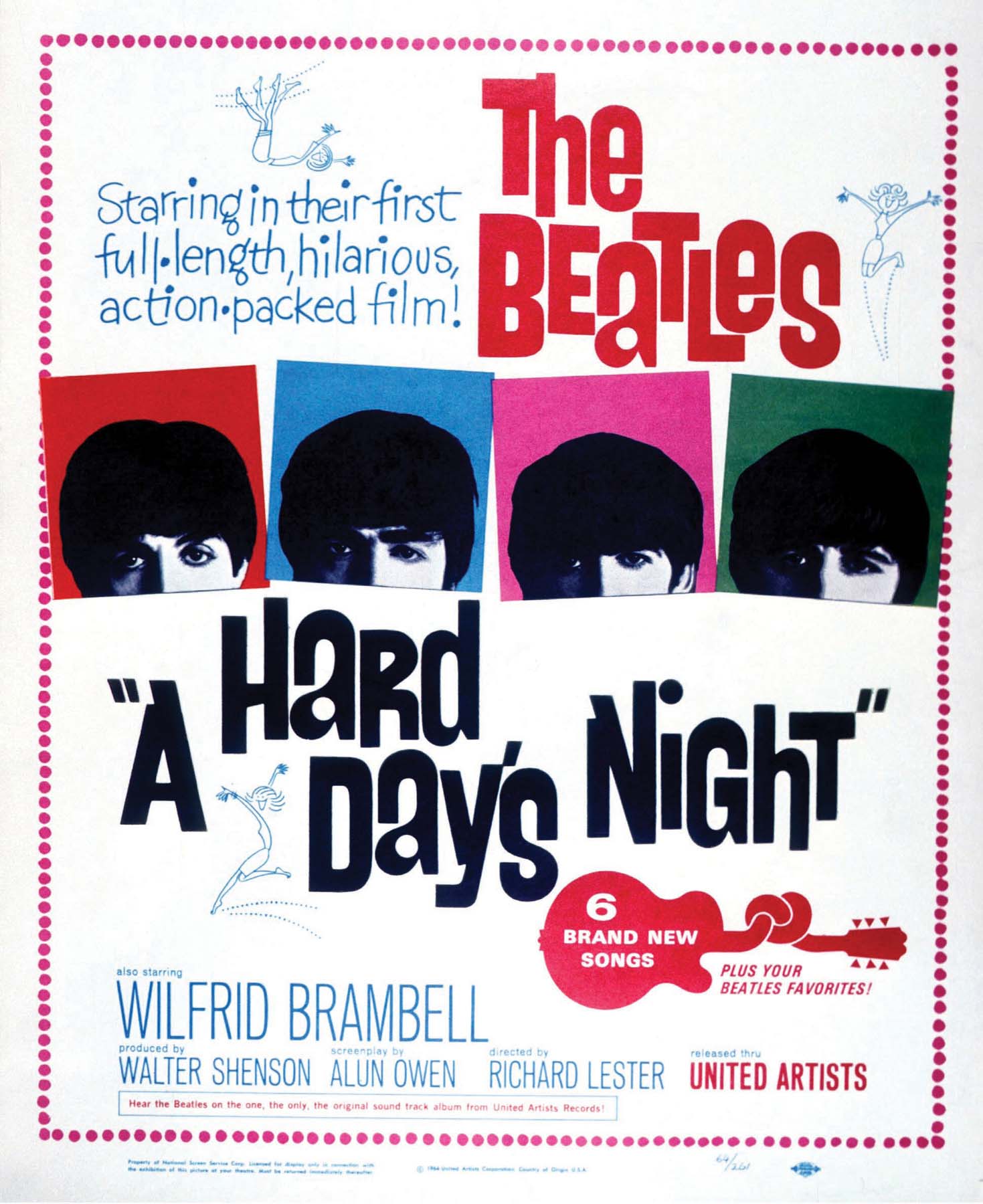

A HARD DAY’S NIGHT

SHENSON/UNITED ARTISTS, 1964 | BLACK AND WHITE, 87 MINUTES

DIRECTOR: RICHARD LESTER PRODUCER: WALTER SHENSON SCREENPLAY: ALUN OWEN SONGS: JOHN LENNON AND PAUL MCCARTNEY STARRING: JOHN LENNON (JOHN), PAUL MCCARTNEY (PAUL), GEORGE HARRISON (GEORGE), RINGO STARR (RINGO), WILFRID BRAMBELL (GRANDFATHER), NORMAN ROSSINGTON (NORM), JOHN JUNKIN (SHAKE), VICTOR SPINETTI (TV DIRECTOR), ANNA QUAYLE (MILLIE)

A day in the life of the Beatles, with interference from Paul’s grandfather.

A Hard Day’s Night is an everlasting delight, and not simply because it stars probably the most famous rock group of them all. It was, and is, the nature of pop phenomena that fame and idolatry hit fast, burn brightly, and peter out. Even in these, the Beatles were different: their music had far more craft and substance than usual, and their personalities and look were engaging without seeming affected. There were also the fans: endless millions of mainly young women screaming and swooning with an intensity that put earlier mobs to shame. Given the furor, it was inevitable that the Beatles would star in a film, just as Elvis had done and other singers would do throughout the entire history of sound film. Far less predictable was the fact that their movie was a work of wit and joy.

Depicting a slightly fanciful version of the real quartet, A Hard Day’s Night takes an amused look at sudden celebrity and its impact on four nice, if occasionally bewildered, young men from Liverpool. Paul is reasonably self-aware, George lives on his own island, Ringo has a chip on his shoulder, and John is something of a benevolent, impudent madman. Together and sometimes separately, they must cope with cosmic fame, near-rabid fans, unreasonable professional demands, and Paul’s appallingly mischief-prone grandfather. Their inherently good natures always see them through, at least enough to keep them grounded and able to perform some truly wonderful songs written by John and Paul.

Paul McCartney, George Harrison, Ringo Starr, John Lennon

The Fab Four would have read well on film under nearly any circumstances, but it is director Richard Lester who turns them into cinematic conquerors. Working with the same low budget as other rock movies, Lester made a virtue of the imposed limitations by bringing imagination and energy to the fore, using the songs as background scoring and in performance, without bogus integration. The music, as depicted here, is what keeps the quartet grounded, along with their senses of humor and of the absurd. Only on rare occasions are they allowed to escape the chaos and screaming, as in their playground romp to “Can’t Buy Me Love.” Here, especially, is where Lester cuts loose as much as the Beatles, with the same manic editing that, in less than two decades, would form a cornerstone for the new realm of music video. This is one of many repercussions A Hard Day’s Night would have on film and rock music. It looked ahead to the documentaries of later years, even “mockumentaries” like This Is Spinal Tap, and to new ways to promote and market musicians.

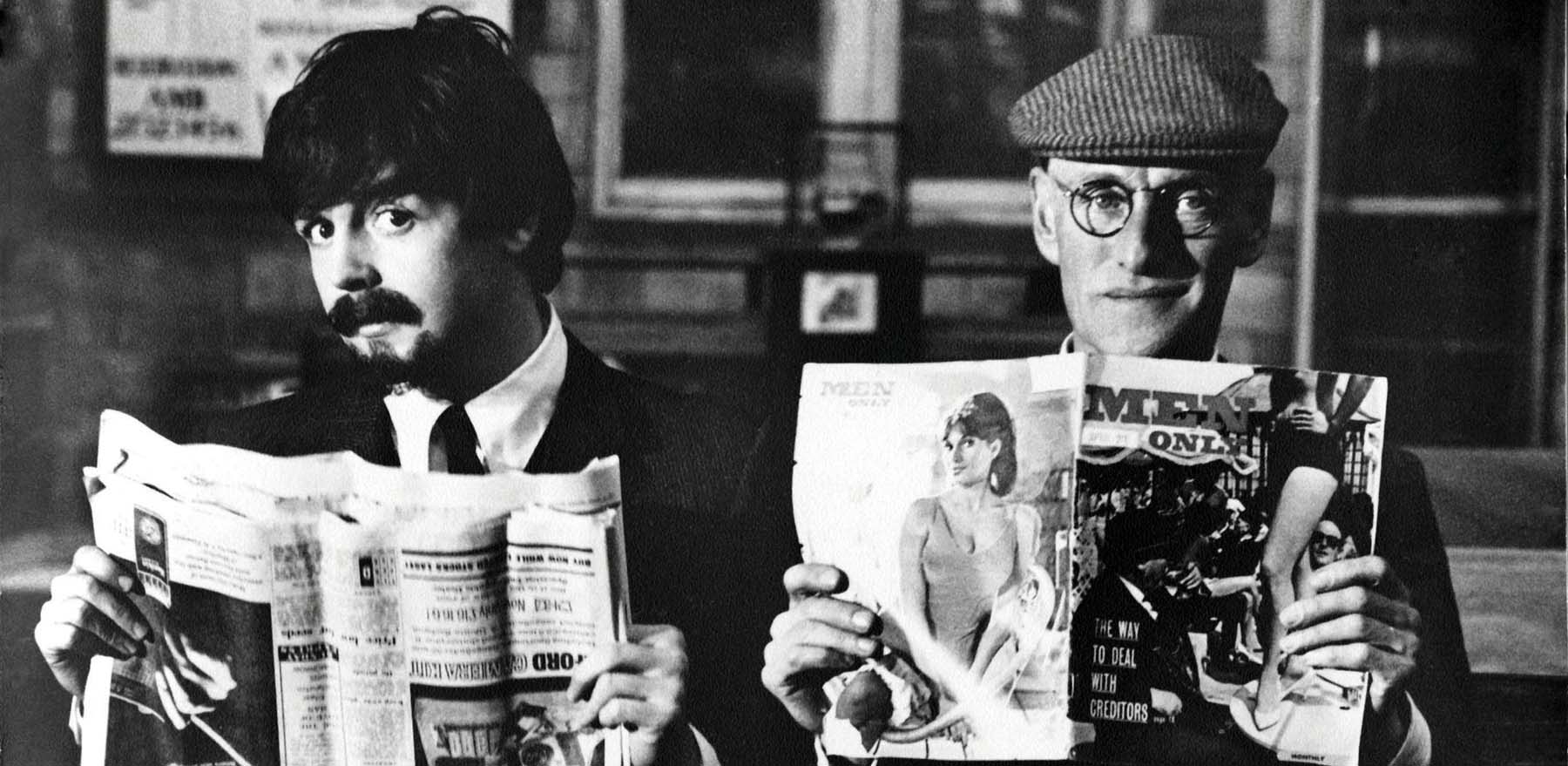

Paul McCartney and Wilfrid Brambell

Most importantly, it showed that, where pop music was concerned, film could be far more than simply an ancillary prop. Seldom did its emulators come close to the original, not even when the Beatles reteamed with Lester a year later for a follow-up. In Help!, the frenzy of the fans is replaced by a great deal of running around, and the near-documentary feeling has morphed into brightly colored nonsense. (Still, however, with really good songs.) Only the later animated Yellow Submarine and the documentary Let It Be lay ahead, on film, before the Beatles disbanded. And what a legacy.

When A Hard Day’s Night was being initially planned, someone probably had the notion that a Beatles film could be done fast and cheaply, make some money, and be fast forgotten. No one, it’s safe to say, envisioned that it would be a groundbreaker, let alone a classic movie musical. The Beatles broke all kinds of rules, didn’t they?

WHAT’S MORE

The near-poverty-level budget for this film was a sure indicator of how little United Artists believed in it. The company was, in fact, far less interested in producing a movie than in releasing a soundtrack album, to be issued on United Artists Records instead of the group’s usual label, EMI/Capitol. Few involved would have predicted that in its first week of play in the United States, in a time long before make-or-break opening weekends, A Hard Day’s Night grossed something like sixteen times its original cost.

If the film’s off-the-wall brilliance was a surprise to everyone, there was some advance notice that this was an unconventional project. The coming-attractions trailer, shown in many theaters, interspersed clips from the film—mostly of screaming fans—with a scene of the Beatles discussing the film while comfortably seated in a pair of baby carriages. Imagine Elvis, or anyone else, doing such a thing.

MUSICALLY SPEAKING

The concert near the end is both a valuable record of the early-prime Beatles style and an accurate depiction of how their audiences behaved. It was shot in London’s now-demolished Scala Theatre on March 31, 1964, with, as is quite apparent, a live audience. (“You Can’t Do That,” filmed as part of the set, was cut at the last minute. The footage survives.) Among the male minority in the crowd is a future star: the thirteen-year-old Phil Collins can be spotted if you know where to look. It took little direction to get the audience to yell uncontrollably and cry hysterically; they were at a Beatles concert, and such things came naturally.

Ringo Starr, John Lennon, George Harrison, director Richard Lester, Paul McCartney on the set