III. The New Victims & the Power of the Public

A classic definition characterises the scandal as a communicative event that reveals a “moral lapse of high-ranking persons and institutions”[1] - and whips up the moral outrage of a public whose judgement is otherwise considered more or less irrelevant. It can thus be assumed that the scandal requires a plunge from a certain height simply for dramaturgical reasons and that it owes the attention it generates particularly to the ruin of once celebrated heroes whose reputation suddenly and spectacularly implodes. According to this concept of the old mass-media dominated world, the journalists are the scandalisers, the mighty and the well-connected are the favoured objects and victims, and the members of the public form but the tail end of the communication process. They form the elements of a largely diffuse and rather passive mass whose influence is limited to honouring a bid of scandalisation with media consumption and occasional commentaries.

“No scandal breaks loose against powerless or little people” is a representative statement in an early publication on the Phänomenologie des Scandals [Phenomenology of the Scandal].[2] This kind of absolutist diagnosis is certainly no longer adequate, and probably never was. The popular (“gutter”, “yellow”) press - tabloids and broadsheets - has always scandalised the behaviour of the powerless and the so-called little people. They have attacked purported or actual offences and produced innumerable victims by infringing their private sphere (which is, of course, part of the business strategy of this kind of popular press).[3] The reality in today’s digital age is, however, that revelatory stories are directed at powerless and completely innocent people to a previously unimaginable extent. The stories and destinies of these victims are changing our conceptions of causality and proportion because they often show a seemingly strange asymmetry of cause and effect, occasion and consequence, offence and punishment. Even trivial things may now be given the scandal makeover, independently of the emotion-mongering industry of the popular press. Even completely unknown people may gain doubtful ad-hoc celebrity if the public reacts accordingly. The public may, for instance, unimpressed by the relevance prescriptions of the mass media, independently demand accountability for a self-defined grievance and thus turn from a recipient into an originator of scandals.

How should the stories of a sudden public outrage be assessed? Do they express the wisdom of the many extolled by James Surowiecki?[4] Or do individuals tangled up in a mass lose their sense of moral judgement, as Gustave Le Bon argues in his psychology, which is permeated by a pessimistic view of culture and a profound hatred of collectives?[5] Who is right? James Surowiecki or Gustave Le Bon? The answer: there is evidence to support both positions. Media consumer audiences in the digital age demand information and enlightenment at breakneck speed. Those seeking outrage gang together in a flurry and succumb to the storm of their cravings for revenge. In the extreme case, such clamouring for norm control leads to self-administered justice and anonymously-driven manhunts. Consequently, the morally inspired effort to perform control fails to control itself. Scandals of a second order arise - perhaps again registered and commented on by an attentive and morally sensitive public that now declares the means and manner of scandal mongering to be the real scandal. However, this does not always help the victims of an attack directly and immediately, even though they are unexpectedly given protection, because the stigma and the injuries will tend to linger on, albeit in altered circumstances, and all the critical commentaries and counter-commentaries may tend to fan the flames for even higher surges of outrage. The situation is only saved when the attention of all the participants begins to wane, at some later stage, and finally fades away.

1. The hounding of Gao Qianhui and the emergence of a cybermob

Careless self-demolition

On 12 May 2008, a dramatic natural disaster occurs in the province of Sichuan in southwestern China. An earthquake of magnitude 7.9 on the Richter scale kills more than 69,000 people, injures about 375,000. The Chinese nation is shocked by the catastrophe. A week later, the government decrees three days of national mourning in remembrance of the victims of this earthquake. For three days flags fly at half-mast in the entire country, for three days discotheques and karaoke bars remain closed. Even the Olympic torch relay is interrupted. In addition, big Web portals present themselves in the Chinese colours of mourning. Access to games and other entertainment sites is blocked.[6]

This reaction of the state to a catastrophe prevents 21-year-old Chinese woman Gao Qianhui from Shenyang, the capital of the province Liaoning in the northeast of China, from playing her favourite game. She is sitting in a computer room - or possibly an Internet café - and is simply furious. She is not only angry with the government that has blocked her game but with the victims of the earthquake who, to her mind, are to blame for the Net shut-down. To vent her anger she switches on the webcam of her computer and films herself while indulging in a thoughtless outburst, a so-called rant, an uncontrolled fury and hate speech that will ruin her reputation forever and will also soon after lead to her arrest by the Chinese police. In this soliloquy, which she herself publishes later, she vents her views on the earthquake and its victims. She is sitting there with folded arms talking to the camera with no sign of compassion: “I turn on the TV and see injured people, corpses, rotten bodies. [...] I don’t want to watch these things, I have no choice.” She carries on talking monotonously without pause, swearing and railing. “Come on, how many of you died?”, she asks. “Just a few, right? There are so many people in China anyway.” And then: “You’re driving everyone crazy. [...] What are you doing! Do you think you’re all that good-looking?” Qianhui states that the earthquake was not strong enough for her. She makes it clear that she would not have had anything against a few more victims. She also complains about the donations for the people in the affected region: “People are giving you cash and giving you food. And you guys are doing nothing?”

The hate diatribe of the young woman lasts for about five minutes. From time to time other people appear in the background, who watch Qianhui ranting against the earthquake victims. The resulting film is eventually published by the 21-year-old on the video platform YouTube on 20 May 2008.[7] The very act of publication demonstrates a peculiar blindness towards media and situations. Her technical skills to create publicity stand in no relation to her communicative competence and her ability to anticipate the potential effects of her actions. Obviously, Gao Qianhui does not realise that her film can now be watched the whole world over. Obviously, she completely lacks the sensitivity to appreciate the effects of her effusions in a phase of national mourning to remember the victims. She seems unaware that there are utterances that are restricted to the discrete backstage sphere and will produce harsh condemnation when presented in the front region. Her story is an exemplar of a great number of self-documented and subsequently even self-revealed norm violations that elicit processes of scandalisation on the Net, which precede the unleashed scandal and simultaneously supply the necessary material to the community of scalp hunters.

Figure 7: Gao Qianhui during her hate speech against victims of the earthquake.

The search for human flesh

The wave of outrage rolling over the young woman in the days after 20 May exceeds all expectations. The event reveals, at the same time, what the conditions are that generate a vengeful cybermob.[8] The prerequisites for the emergence of such a community of outrage and fury are: a broad consensus about the repercussions of the observed norm violation; an unconditional readiness to indulge in outrage fed by moral rigorism in a collective; the belief shared by the members of this collective in being able to achieve a great common goal by using easily available means of communication - without running any risks themselves - the goal being to harm the culprit, and to redress her offence through a common act of self-administered justice. The prompter for the collective hounding of Gao Qianhui is the epidemic spreading of her video. It is posted rapidly on all the significant Chinese discussion forums and duplicated repeatedly on YouTube. Several variants are produced, including different versions with English subtitles, all increasing the number of international viewings. The Chinese woman is berated in specially produced video replies; during the first night after publication, at least a dozen of such clips are uploaded onto YouTube.[9] Under the online article of the Chinese news agency Xinhua alone more than 29,000 commentaries accumulate.[10] It is a so-called shitstorm that has broken loose.

Shitstorm

In Germany the expression refers to a storm of outrage that is sparked off online and rapidly escalates on the Net. It may be directed at individuals but also at groups and enterprises.

However, the shitstorm does not stop at the mere articulation of disgust and outrage. “Now humiliate her”,[11] an agitated Internet user demands - and with this appeal documents the decisive reorientation and radicalisation of the cybermob. The enraged swarm is now rooting for compensation in real life - but without even a moment’s hesitation to consider the essential feature of the criminal justice process in Western democratic societies: the requirement that crime and punishment be placed in an adequately balanced relationship. A sentence is passed only according to a strictly regulated formal procedure by a judge who has heard evidence and arguments from prosecution and defence. The judicial and the executive powers operate independently. At this stage of relentlessly rising self-righteous anger, at the latest, a peculiar paradox manifests itself: the attempt to control and sanction insubordinate behaviour by way of self-administered justice derails itself. The hounding of the scandal targets becomes scandalous in itself, and the desire to persecute the angrily commented violation of a norm changes into the violation of a norm in its own right. “Why did so many nice and innocent people have to die. And she is still alive?” a user asks under a copy of the YouTube video. And another one: “You are full of shit! Every Chinese hates you now! You have no place to go to!” “If she is really serious we should simply shoot her in the head”, writes someone from under the safe cloak of anonymity. And: she should suffer a slow and painful death! Qianhui’s family is equally targeted by the hate of the mob, e.g. “I hope your entire family is killed by the insulted relatives of the victims”. Numerous rumours about Qianhui circulate on the Net. She is at first wrongly identified as Zhang Ya.[12] Then clearly faked messages and declarations of remorse from her family appear, still using the wrong presumed name, however, and therefore identifiable as fakes even from a distance. There is this passage, for instance: “Zhang Ya is my daughter, and as parents, we have failed in educating her. [...] I can only say to the people of Sichuan, the people of China: I’m sorry!”[13] Then the purported mother implores everyone not to harm her daughter. In another message a user claims to be the young woman’s brother: “Hello to all netizens, I am Zhang Ya’s brother. [...] After watching this video, to tell you the truth, I’m also disgusted.”[14] But it does not take long to correct this because the outraged group collaborates closely in order to establish even the minutest details about the life of the 21-year-old woman and to distribute everything in numerous chats and forums.[15] Soon her private and her work address are known and that her parents are divorced. Even the number of her identity card is published - and all this in hardly a day![16] The example also allows us to observe the detective work of the cybermob, which operates according to the principle of crowdsourcing, in Chinese referred to as the search for human flesh (“Renrou Sousuo”).

Therefore, we are not dealing here with an ordinary query that just happens to be launched by many people more or less simultaneously. The intention of the outraged collective is much rather to publicise the identity of individual persons in order to render them directly vulnerable in greater measure. The aim is to transform the online hounding into a real life hunt in order to harm the incriminated persons in every conceivable way: by threatening calls to the family, by denouncing them to employers or colleagues, by exposing and humiliating them in their immediate social environment.[17] On 21 May 2008, i.e. only one day after the online publication of her video, Gao Qianhui is arrested by the police in her home town of Shengyang[18] - allegedly in an Internet café. The reason remains unclear. Some sources say that the police did not indicate what law she had broken. Other media report that the young woman was arrested on a charge of “malicious gossip“[19] or “on charges of endangering public stability”.[20] She is supposed to have been held by police for three days. It is unclear what happened to her after that. She disappears abruptly and without trace from the media following the days of her arrest.

The search for human flesh

Originally, this expression - with its apparently menacing undertones - (Chinese “Renrou Sousuo”) did not have any sinister ring; it simply meant an operation of research carried out collaboratively by several people. Gradually, however, the search by people turned into a search for people who had committed a purported or actual offence. Today the expression stands for an aggressive form of self-administered justice, a witch hunt according to the conditions of modern media. Its goal is to search out and publish private information and intimate details, to identify accused persons in an act of vengeful cooperation in order to harm them and possibly also their families as severely as possible. Numerous cases of this Chinese search for human flesh have since become known. And the old and harmless meaning of the expression “Renrou Sousuo” has slowly disappeared.

2. The fate of the student Wang Qianyuan and the clash of cultures

Cause and effect

Amongst our conceptions of a calculable, controllable world is the notion that our intentions can be realised through actions that generate reasonably predictable effects within the field of human relations. The underlying assumption is that a cause produces an effect in a linear progression. We can refer an effect to a specific cause. Cause and effect stand in some adequate relationship with each other, following a kind of rule, as it were: weak triggering forces generally produce marginal effects; strong massive causes, by contrast, generally produce strong effects.[21] In the scandalisation processes of the digital age this common sense concept of ordered causality, relying as it does on popular views of clear sequences of steps, proportionality, and a hierarchy of forces, is not necessary applicable any more because now things tend to happen in circularly enmeshed chains of effects so that completely unexpected feedback phenomena may occur. In addition, even stimuli that may at first glance appear minimal (some spontaneous behaviour, an ad-hoc utterance, sudden flashes of insight that ultimately prove disastrous) can potentially have massive consequences. These consequences may turn out to be contrary to the original intentions of the participants, but also contrary to the intentions of persons whose autonomous activities are suddenly unhinged and whose goals are thwarted in a blatant manner. This is aptly illustrated by the story of the 20-year-old Chinese woman Wang Qianyuan, language student at Duke University, USA. On the evening of 9 April 2008, she is on her way to the library and encounters two groups, or better clusters, of demonstrators.[22] On one side, there are a few dozen supporters of the liberation of Tibet. They wave Tibetan prayer flags and banners with the inscription “Free Tibet!”, distribute flyers and draw attention to the destruction of Tibetan culture and the massive infringements of human rights. On the other side are more than 100 Chinese demonstrators, who are enraged by this act of allegedly anti-Chinese propaganda because they consider Tibet to be part of the Chinese state. They thus feel provoked and humiliated by the pro-Tibet demonstrators. Lies are being spread here, they shout. Both groups face each other with increasing signs of intransigency.[23] Slogans are chanted, both sides berate each other. At times the confrontation seems on the brink of turning violent.

A balancing act between the front lines

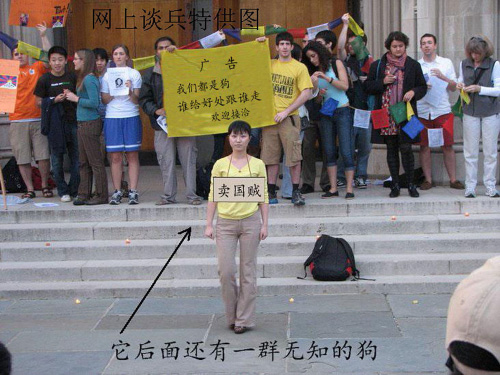

The threatening escalation is not the result of a conflict between the Tibetan people, the followers of the 14th Dalai Lama, and the Chinese nation alone - a conflict that has been smouldering for decades. It is also the result of a concrete historical moment, the manifestation of an extremely heated atmosphere in the preparatory phase of the Olympic Games in Beijing, which is characterised by Chinese nationalism, on the one hand, and many actions of protest in non-Chinese countries, on the other.[24] The torch relay with the Olympic flame, which runs through different continents, has to be repeatedly interrupted and redirected in the days and weeks before the events. In London, demonstrators stop the torchbearers, in Paris the torch relay is cancelled, in San Francisco the routes are varied, in New Delhi the public is for safety’s sake prevented from viewing the solemn handing over of the flame in order to avoid causing unrest. Wang Qianyuan, student and ad-hoc protagonist of an inter-cultural conflict and an ultimately dramatic communication failure, is not aware of the demonstrations on the campus of her university on the evening of 9 April. She runs into them quite by accident and tries to mediate because she spots familiar faces in both camps and assumes that her knowledge of languages might help to create mutual understanding on both sides. She is filmed and photographed running back and forth between the two groups, gesticulating excitedly, trying desperately to initiate a dialogue. One of the pro-Tibet demonstrators eventually asks her to write the slogan “Free Tibet!” on his back with a felt pen - which she does, but not without wresting the promise from him to make contact with the pro-China students afterwards. In the end, however, she cannot placate him either, she is attacked as a “traitor” because she speaks English, because she uses the language of the adversaries and is therefore seen as a supporter of the causes of the Tibetan government in exile. The bystanders ask for her name and her place of origin. Unsuspecting at first but increasingly worried she provides the information and tells them about her school in Qingdao. The threats become more and more massive, however (“You should be careful, you could be killed!”), and as a result she finally has to be escorted back to her student lodgings under police protection. In the early hours of the morning, she commits a momentous mistake by trying to explain her actions, to eliminate misunderstandings and to calm emotions. In the online forum of Chinese students and lecturers at Duke University she writes an open letter to her “dear compatriots”.[25] It is a communicative balancing act between the hostile camps, an effort to create understanding for both sides. Wang declares that she is not at all for the secession of Tibet, she criticises the lop-sided reporting of Western media, quotes Taoist and Confucian ideas and refers to the traditions of wisdom that suggest working with the forces of the enemy in order to realise one’s purposes in a quiet and considerate way and manner, not with loud screaming and by way of aggression and repression. She pleads for tolerance and for treating her Tibetan fellow country people in a more friendly and equitable way because their repression would only fuel rebellion and hamper their smooth integration. The next morning she registers, as she will say later, “a storm was raging online”.[26] Most of the photographs published on the Net show her on the side of the Tibetan demonstrators. There are defamatory montages showing her half-naked. There are images similar to a “Wanted” poster with her face on them, which accuse her of betraying her people and her nation. A video of the demonstration is circulated that shows her attempts at mediation but has now turned into evidence for an anti-Chinese attitude. Wang has finally lost control over the meaning of her utterances. What she said and what she tried to do is now no longer determined by herself but by others - due to the transfer of the data and documents to another cultural space and thus to another sphere of meaning and interpretation.

The loss of inhibition in online communication and its effects

The commentaries published in popular Chinese forums are examples of the negative effects of online communication dominated by anger and hate, which the American psychologist John Suler has investigated.[27] They document the comparatively risk-free discharging of the aggression of a cybermob that can at least be facilitated and enhanced by different features of that form of communication. The attackers believe that they are safe from persecution because they do not have to reveal their identity and shoulder any responsibility in real life. Whatever they say online is not connected with their offline existence as their own personal life remains invisible for the others and cannot be touched by potential feedback from those persons that have been labelled as enemies. They agitate from under the cloak of anonymity (or perhaps more precisely what may be called: pseudonymity),[28] they have no face-to-face contact with the accused that might lead to more discriminating and empathic communication. They have themselves no feeling for the suffering of their victims and they are not confronted in their own immediate personal world with the consequences of their actions, they cannot and are not forced to see what they have set in motion. Some of them possibly consider the digital universe as a parallel world that is governed by their personal inclinations and experimental desires and in which they do not have to feel bound by accepted conventions and authorities. A brief selection from the list of threats and insults that were published as early as 10 April 2008, the day after the demonstration, may illustrate the dimension of the aggression: “I want to see photos!” - “I shall not let that bitch even five metres near me.” - “Croak it, shameless thing.” - “What? From the Qingdao Middle School? Makes us lose face in this way? Execute her on the spot.” - “Inform the Ministry for State Security, the Chinese Embassy and her home district.” - “Call the machine for the search of human flesh!” - “Evidence is important! We do not want to damage anyone who is innocent. But we shall never leave the wicked in peace!” - “Alarm the Customs officers to catch her, and if she has family seek them out and beat her shameless children to death, so that they can no longer harm the Chinese people.” - “Traitor of our race! Traitor! Sooner or later your whole family will pay for this.”[29]

However, the reactions do not remain restricted to verbal attacks; meanwhile the so-called search for human flesh has begun. The mob aims now at exposing her family and her person, seeks the existentially jeopardizing attack, the destruction of a life’s career. Shortly after the first enraged attacks her telephone number, her mail address, and the numbers of her and her parents’ identity cards all circulate on the Net. Wang is convinced that this kind of information can only have come from the Chinese police. Detailed navigating instructions to the house of her parents are discovered, also information on where the parents work. It is even detected without any difficulty what kind of musical instrument Wang once learnt and played. The consequences are massive. In her home country, the Qingdao Middle School revokes her final exams and vows to practice a more patriotic education in the future. It is rumoured that the authorities of the state have put her name on a sort of blacklist containing the names of people who are to be punished severely when returning to their home country. As she cannot be apprehended directly - the police controls on the grounds of Duke University are increased in the days following 9 April - various individuals attack her parents directly, forcing them to go into hiding. Their windows are smashed, their house entrance is smeared with excrement and slogans: “Kill the whole family! Kill traitors of our country!”

Figures 8 + 9: The enraged mob acts online and offline. The first figure shows a digitally re-edited photograph of Wang Qianyuan with a sign “Traitor of the country” around her neck; in the background one can recognise the pro-Tibet demonstrators. In the second image, one can see the slogans on the wall of her parents’ home: “Kill the whole family! Kill traitors of our country!”

The scandalisation of scandalisation

What makes the case so illuminating, however, independently of its dramatic private-personal features, is the fact that the outrage on the Chinese side is contrasted by a diametrically opposed assessment on the side of the Americans. It becomes clear that the sensibility for scandal - as the sociologist John B. Thompson notes - depends on the particular historical moment in time, on the general cultural and moral climate of this historical moment, and on the value orientation and the hierarchy of the values of specific groups or even whole nations.[30] The action that is so angrily attacked by a Chinese public as the violation of a norm is glorified in the United States of America as a norm-confirming behaviour worthy of special praise. A group of Cuban American students of the University therefore takes Wang’s side: “We admire Wang for standing up for her beliefs, in spite of the personal repercussions inflicted upon her by an oppressive regime. She does not stand alone.” The Washington Post publishes an extensive reaction by her and even prints special reports on the case.[31] Other leading newspapers devote prominent space to the case; the New York Times even deals with the topic on its front page.[32] These reactions illustrate that the Net has provoked this ideological conflict of weltanschauungen and a clash of cultures that is enacted on a globally visible stage. On one side are the Chinese nationalists who hound a traitor and who insist on interpreting her interviews given to US media as signs of a hostile attitude. On the other side are the representatives of Western democratic values to whose central canon of values belongs the right of free speech and the free voicing of opinions. But this is not yet the end of the story. Reconstructing this process of scandalisation makes abundantly clear that the scandalisation of the purported treacherous position of Wang’s from the American side is answered by a reactive pattern of outrage that could be termed scandal of the second order. Individuals, specific groups, or even whole nations may view a process of scandalisation as scandalous in itself and consequently perform the scandalisation of a scandalisation. The actual scandal, it is assumed, is the way and manner in which the other side proceeds, vents its anger, and - it is thought - practises its outrage in an unjustifiable way due to the disregard of central values and norms. The implication is: the observation of scandalisation leads to the scandalisation of the scandal that is, consequently, contextualised, evaluated, and classified anew in a totally different way.[33] Thus, there is praise for Wang’s education and her effort to argue for a compromise. Some commentators describe Wang as an icon of the right to freedom of speech and the commitment to enlightenment. Her concern for an open dialogue must be protected at all costs. The commentators on the Chinese side are called downright barbarians. The organisers of the pro-Tibet demonstration, the Duke Human Rights Coalition, published the following statement: “Duke Human Rights Coalition condemns, in the strongest possible terms, the threats made against Grace Wang and her family. As fellow Duke students, it is our responsibility to foster an atmosphere of tolerance, respect and academic freedom. The fact that a Duke student has been targeted for speaking her mind at the University is an incredible violation of that same freedom. We should not be bickering, or searching for someone to blame; we should be banding together as a community to protect a fellow student.”

This student Wang, who is praised in a foreign country and hated in her home country, again reacts in an extraordinary way in her letters and interviews, in her statements and analyses, and publicly declares that she has rejected her father’s suggestion to apologise. She insists that she does not wish to retract anything, and she explains and promotes her perspective in a surprisingly unruffled way, anxious to stall any further escalation in the sphere of communication. Only two days after the éclat on the university grounds she publishes an extensive essay in the pro-Western China Digital Times which is produced by students in Californian Berkeley. This essay, a masterpiece of dialectic argumentation, is entitled The Old Man Who Lost His Horse and starts with the following parable:

During the Han Dynasty - in the third century B.C. - an old man living on China’s border one day lost his horse. His neighbours all said what terrible luck that was, and sympathized with the old man. But Sai Weng said: ‘Maybe losing my horse is not a bad thing after all.’ Lo and behold, the next day the old man’s horse returned, together with a beautiful female horse alongside him. All the neighbours exclaimed: ‘What great luck!’ But the old man responded: ‘Maybe this is not such good luck after all.’ The old man had a strong young son. The boy fell in love with the new horse and rode her every day. One day the new horse got spooked by a wild animal and threw the boy from her back. He broke his leg very badly and was permanently crippled. All Sai Weng’s neighbours said: ‘What a tragedy, your strong son will never walk without pain again.’ But the old man again said: ‘Maybe this is not such a bad thing after all.’ And so it went that when the New Year came, the emperor’s army passed through the border region and recruited all able young men to fight in the frontier war. Because the old man’s son was crippled he could not fight and was left in the village to farm with his father. Sai Weng said to his neighbours: ‘You see, it all turned out okay in the end. Being thrown from the horse and breaking his leg saved my son from fighting in the war and almost certain death. So it was in the end a lucky thing after all.’ Whenever a bad thing happens in China, someone will say ‘Sai Weng Shi Ma’ (Remember ‘The Old Man Who Lost His Horse’) to remind themselves and others that apparently bad things sometimes have a silver lining.

At the end of her essay she provides her own dialectically founded justification of the norm violation. The violation of the norm, she explains, is an occasion to understand the value of the norm and to learn to appreciate it, an opportunity of directly experiencing the crossing of a frontier, of appreciating the meaning of the frontier.[34] “Like the old man who lost his horse”, Wang Qianyuan writes, “I am determined to turn this apparent misfortune into a positive experience and equal opportunity for learning and growing for my fellow Han Chinese, Tibetans and Americans.”[35]

3. The humiliated husband and the divorce battle of Tricia Walsh-Smith

The chameleon and the mirror

It is a strange question.[36] In the year 1974, the journalist Stewart Brand pays a visit to the cyberneticist Gregory Bateson. Stewart Brand, who makes the pilgrimage to this old man like many others, wants to know what colour a chameleon assumes when you put it on a mirror. Bateson has no answer. Nevertheless, he - the cyberneticist, the master of circular thinking - is fascinated by the question and circulates it amongst his students and the scientific community. Various researchers enter the debate. A technically gifted writer constructs a cabinet of mirrors and places a real reptile in it to find out what actually happens if you put a chameleon on a mirror. What colour will it assume? Will it retain its original colour tone? Will an iridescent and characteristically unstable kind of oscillation emerge? Will the chameleon be driven into a sort of colour madness in this world of mirrors? Will it for the sake of self-defence finally settle for a sort of basic colour, a kind of colour identity? The fascinating aspect of this question is that the chameleon and the mirror seem to fuse, that the logic of linearity is replaced by a circular network of effects.[37] Perhaps the actual outcome is not of such great importance. We prefer to imagine that we are involved in a thought experiment that throws a dazzling light on the development of the modern media, throwing into relief some of the relevant questions in connection with the current situation of the omnipresent digital media. What happens to people who live in the awareness that they are surrounded by mirrors and that the mirroring of their very personal selves may be exploited for strategic purposes? In what ways, for example, do we medialise our own history as soon as we have realised that the most visible, the most intensive mirroring, requires a specific colour code? How do we generate attention and communicative connections, and how do we scandalise for private purposes?

A reality soap for one’s own ends

The actress Tricia Walsh-Smith from New York answered this archetypal question about effective self-presentation in the modern media’s hall of mirrors in her own way in the year 2008. Her strategy: self-staging according to the current rules of medial staging as practised by independent external professionals, in particular, targeted self-medialisation following the pattern of a reality soap. Tricia Walsh-Smith tried to use the concentrated power of Web 2.0 to terrorise her husband, who was pushing for a divorce, to scandalise his behaviour, and to transform the approaching court proceedings into a tribunal in the public sphere intending to shore up points in the divorce poker and secure a television career afterwards. Her story, or all that one knows about her, is terribly banal - but nevertheless instructive. It demonstrates in what ways one can exploit the rules of the games of show business and reality television by adapting to them chameleon-style, in order to generate attention and communicative connections - at least in the short term - by polarising the public. The medial script thus becomes the apparently authentic self-expression of her individuality and her private history. The background story of the reality soap that she fabricates for herself is easily summarised: when her husband Philip J. Smith files for divorce after nine years of marriage, she chooses the best known of all multimedia platforms for defaming him. She underlines that he has, of course, the best contacts with the most important mass media in New York, whereas she has no access to these media and is therefore dependent on other channels. The then 52-year-old actress publishes a first video in April 2008, in which she divulges intimate details from the life of husband Philip J. Smith, millionaire Broadway impresario, who is 25 years her senior, and presents herself as a pitiable victim.[38] She had specifically engaged a professional cinematographer for making this barely six-and-a-half-minute YouTube video, so that the result was a professionally cut film with a proper sound track. In this film Walsh-Smith accuses her husband of planning to evict her from the shared Park Avenue apartment in New York within the next 30 days. She admits that he was entitled to do that on the grounds of their marriage contract, although only for legally just causes - that, however, did not exist. “I don’t know why”, she sobs with tears in her eyes. The image is faded out. Then she adds abruptly: “Another thing. We never had sex.” He had always used his purportedly high blood pressure as a pretext and she had naturally accepted this. However, she had discovered a year back that he must have used potency drugs, unambiguous films, and condoms. Walsh-Smith passes on these private-intimate details to her husband’s secretary on the telephone. She thus chooses, quite generally speaking, a popular strategy used by obscure persons and minor celebrities, who do not really have an important story to tell or cannot offer any item of information or piece of news of public relevance, but who are terribly keen on parading themselves in public before the world, cost what it may. This kind of strategy is only too familiar from the affect-and-scream shows of afternoon television, from shows with celebrities, and from celebrity magazines. Their goal is to arouse attention and to promote the medial mirroring of the involved persons’ egos. And their basis is a kind of exchange liaison in its own right: intimacy, curiosity, and vulgarity for publicity.[39] In accordance with this scheme and by way of the direct implementation of such an exchange Tricia Walsh-Smith on camera asks her husband’s secretary, who is totally outfaced by this approach, to enquire with Smith - her husband still - what she should do with the Viagra, with the pornographic films, and the condoms.

Figure 10: First instalment of a reality soap for her own ends: the YouTube video with which everything started.

Then the show goes on. In the living room, Walsh-Smith shows photographs from the wedding album. She pithily comments on the images of members of her husband’s family: “This is Philip’s oldest daughter. She is the evil one. She wants my pension. [...] A bad, bad, bad person.” She then leads the spectator through the luxury apartment and turns melancholy. “This is my home”, she says. “Or was my home, which I am being evicted from.” She does not intend to give up, however. At the end of the video she says with wide open eyes towards the camera: “I am trying to be a warrior, maybe I’ll win.” Her video ends with an apparently ironic-satirical cliffhanger in the form of questions, which is probably, judging by the overall context, intended to really be serious: “Will poor, vulnerable Tricia be evicted? Or will mean bad husband do the right thing? Stay tuned!” The soap is designed to go on, it will and it must go on. It appears to have found its audience, at least with this very first instalment.

Polarisation resulting from successful communication

In the first week, on YouTube alone about 150,000 users watch the video, one month later three million have seen it, and to this day just short of four million people have got to know Tricia Walsh-Smith’s first publication.[40] About 8,500 comments have appeared, and users have multiply duplicated the revenge video and uploaded it in other places. The YouTube divorce can thus also be found on platforms like MySpace.[41] On Break.com the video attracts a further 550,000 viewers,[42] and in addition parodies and photo stories on the case as well as angry critical films are now in circulation. For the traditional popular press this YouTube divorce is an extremely attractive subject: here a minor celebrity actress voluntarily fights her war of the roses publicly in front of thousands of people - an as yet unheard-of ploy and manner of using platforms like YouTube. Moreover, Walsh-Smith even manages to publicise her story on international media, especially in Great Britain, her home country, and in other countries.

The reception of the divorce video shows that reactions move between extremes (approval and admiration, disgust and hatred) proving that the communication has been successful. The resulting polarisation of the public, shaking it out of its complacency and forcing it into a debate about the right kind of evaluation, is the decisive prerequisite here for the creation of hype, the sudden excess of attention. On one side, several commentators gather within days that support Tricia Walsh-Smith and admire her attempt to initiate an extrajudicial tribunal in the lobby of the media inferno. This group of people thinks that the alleged behaviour of her husband - the only available description of which is of her, his accuser’s, making - must definitely be rated as scandalous and as significantly more serious than her revenge campaign itself. “What a stupid bum this idiot of a husband must have been” is printed under the original video. “I love what you’ve done!”, another user writes. And another one eggs Walsh-Smith on: “Come on girl warrior, get on with it! We all want a happy ending.” Finally, there are about 2,600 positive comments vis-à-vis about 2,800 negative comments on the original video. A large number of written commentaries and video replies are frankly critical of Walsh-Smith. Someone writes: “I am very sorry about what happened in your marriage but this is absolutely not the way to solve your problem.” Another one formulates very clear disapproval: “Egoistic, brainless gold diggers like her make me sick.” There is a lot of abusive criticism in the commentaries, which shows a characteristic unbalanced change in the dynamics of outrage, an emotional atmosphere, and a climate of opinion that are difficult to control. Precisely because the public now determines the timing of the processes of scandalisation in a hitherto unknown measure, the spectrum of variation of assessments can no longer be harmonised and standardised by the pronouncements stemming from merely a few select media. The consequences may consist in unexpected and sudden fluctuations in positions and images. The active scandaliser may be turned into the victim of a scandal at the drop of a hat. The subject publishing information on nuisances and grievances may all of a sudden become the object of defamation. Moreover, the further resonance - following the sudden excess of attention - will remain comparatively incalculable and subject to enormous fluctuations - another lesson that can be learnt from Tricia Walsh-Smith’s trivial mini-soap. She carries on producing YouTube videos of a similar kind,[43] reports on the development of her story, provides teasers for the instalments to come, organises a donation campaign, asking for money to be sent through the online service PayPal.com. She wants to create a foundation with the name Women Warriors of the World United with the amount of money remaining after the costs of the divorce case against her husband have been met. In another clip she advertises her first pop song “I’m going bonkers!” She underlines repeatedly that the song is available for purchase on iTunes. It is a music video that she stages in the costume and the studio of a dominatrix; and it illustrates the self-conscious and strained effort to capitalise on the achieved attention as rapidly as possible, to cash in on the still considerable public appeal. However, not one of her curious and aggressively body-centred self-advertising videos matches the success of the first one. In the final and decisive divorce court hearing - in a court of law, not on YouTube and not in the public arena - the judge Harold Beeler calls the videos part of a “calculated and callous campaign to embarrass and humiliate her husband”.[44] The marriage contract is valid. She must vacate the apartment in Manhattan and will receive $50,000[45] - a fraction of what she had demanded and hoped for.[46]

Following this court decision, Tricia Walsh-Smith has only sporadically been heard of during the last few years. It is rumoured that she has founded an organisation which is supposed to help women in divorce suits. However, the number of clicks on the videos posted by her after the first successful one appears to be pretty modest. Neither an admiring nor an abusively ranting public pays attention any longer. The simple reason is that she has only partially internalised the categorical imperative of a media chameleon, which is: transform biography and personality into stories that are ever new, that are ever more dramatic! She did not even have enough good subject matter for the second instalment of her video soap. In the first edition of her reality soap, she succeeded in generating attention in audiences of millions. Her news and narration factors were the private-intimate violation of boundaries, the public defamation of her husband, a well-known man in New York, and the weird technical and content innovation of using YouTube as the channel for the new genre of the divorce video. Everything that followed was, dramaturgically speaking, merely the rehash of one and the same content - an endless remix, utterly unsuitable for the wildly fluctuating demands of variation and novelty of a public that is quickly bored. Tricia Walsh-Smith eventually attempted, it was reported, to continue her reality soap with the help of professionals and to secure a show of her own on American television. She sought to change her sudden Net celebrity into a basic version of genuine traditional television celebrity so as to make money in the dominant reality of the market. According to information published in the magazine of the New York Times, the negotiations that initially appeared promising have long broken down. It is not known whether anyone - except the self-crowned protagonist - in any way regrets this.[47]

4. The pillory website for Amir and the joys of defamation

The digital doppelgänger

In the year 2005 Thomas Sawyer is tricked by a swindler and, without being fully aware of it at the outset, avenges himself in a most brutal manner. Everything starts with an auction on Ebay, in the course of which the 23-year-old student from Exeter manages to purchase, under the pseudonym spikytom, a Hewlett-Packard office notebook from a certain amir6626. Sawyer pays the demanded £375 - and then has to wait, so he says, for nearly two months. After this long wait the notebook finally does arrive, but it proves to be inoperable and in essential points does not match the description given by amir6626 on Ebay. “Amir’s” account has meanwhile been deleted, however, and every attempt to contact him leads nowhere. About half a year later Sawyer makes a fool of the cheating trader in front of an audience of millions and administers asymmetric justice. The appropriate proportionate relationship between cause and effect dramatically gets more and more out of kilter in the course of his attempts at scandalisation and his acts of revenge. He first manages to reconstruct extremely private sets of data on the hard disk of the damaged notebook. Then he registers a weblog with the name The Broken Laptop I Sold on Ebay with a free provider and starts a cruel role-play with the following statements: “Hello. My name is Amir Massoud Tofangsazan and I live in Barnet. I’m 19 but pretend to be a lot older and like to pretend that I’m a big businessman when I’m not actually that clever.”[48] The story of the laptop sale follows, allegedly written by Amir Massoud Tofangsazan himself. “Haha genius! Selling a ‘working’ laptop that doesn’t work!”, he pretends to praise himself. Despite the polite requests by the buyer, he declined to return his money. Then he pretended to have moved to Dubai, hoping the buyer would forget about the case. “But he didn’t forget about it. He took the hard disk out and behold! One laptop crammed with pictures that I really should have deleted before trying to sell it!” Ten images follow showing pornographic, foot-fetishist, and bisexual scenes - taken from the hard disk of the laptop, according to Sawyer. All the photos come with short ironic commentaries; some are slightly modified or pixelated. In addition, there are pictures of Tofangsazan himself, there is a scan of his passport, and there are suggestions of what else can be found on the hard disk, for instance banking details and the access specifications for Tofangsazan’s e-mail account with Hotmail.

Here, at the latest, the reader will realise that the blog entry cannot have come from Amir Massoud Tofangsazan himself. Who would voluntarily publish photographs and data of this kind? And the following sentence reinforces the impression that somebody has hijacked another person’s identity in order to wreak revenge: “What else could he do but publish this information on the Internet for the whole world to see what a sad man I really am!” In May and June 2006 updates of the blog post follow as well as a further entry with new risky data from the hard disk. Sawyer publishes private correspondence. And he adds pornographic photographs, pictures of women’s legs on the underground and family pictures to the entries. In June 2006 he reveals his real identity for a moment because now Sawyer writes an entry with the title “A message to Amir” - an attempt to use public exposure for purposes of blackmail, to pronounce his judgement and to execute it.[49] “You know as well as me that you sold me faulty goods”, he writes. However, he now no longer wants Tofangsazan to return the money; he tells him to donate the £375 to a charity organisation and to apologise officially and publicly in order to protect his reputation. In return, Sawyer would remove the photos from the site and replace them with information about the donation and the letter of apology. Nothing of this kind happens, though. In February 2007 he announces - now again under the pseudonym of his antagonist Amir - that he is working on an update of the site. But all that is in fact published about a month later are three mash-ups - obviously retouched photographs that show Tofangsazan, amongst other things, as a goggle-eyed voyeur in front of dancing and sparsely clothed women.

The digital pillory

They are called reportyourex.com, people2avoid.com, iShareGossip.com, or rottenneighbor.com. They emerge and vanish, are suddenly offline one day because their providers have clashed with the laws of their country, because a group of hackers has attacked them, or simply because their producers have lost interest. Despite all their diversity they only serve one single purpose: defamation by scandalising purported or actual violations of certain norms. They are pillory websites, platforms for anonymous mobbing, disgrace on suspicion, ambush attacks. Sometimes bounties are offered, or chases are initiated. The topics to be found here comprise the whole spectrum of behaviour worthy of criticism - depending on ideology and political conviction. There have always been and still are “Wanted” posters exposing pimps and prostitutes and their clients, the opponents of homosexual marriage, drug-taking students, or that show police photographs of alleged or actual criminals (so-called mugshots). There are sites where violence against the opponents of abortion is advocated in an only flimsily disguised way and on which targeted manhunts are promoted. One can find photographs on these pages, also names and addresses, personal data or suggestions that may turn out to be handy when further investigations are required. It is, as a rule, impossible to determine what is correct and what not. There is no opportunity to reply or protest or consider a second opinion; there are only monologues of directed aggression.

Emergence of an epidemic

Sawyer sends an e-mail to all the contacts in Tofangsazan’s Hotmail account - that is all he does to make the site known.[50] Nevertheless the blog is accessed 2.3 million times within three and a half weeks.[51] Four years later nearly 4 million visits have been registered.[52] If all the paths of information are searched out and recovered in detail, then the case illustrates a form of distribution that the publicist Malcolm Gladwell, in his book on the tipping point - the moment of tipping over and collapsing, the dramatic moment of the quality leap - has metaphorically described as an epidemic, without however applying the concept systematically to the sudden excesses of attention in the digital age. “To appreciate the power of epidemics”, Gladwell writes, “we have to abandon this expectation about proportionality. We need to prepare ourselves for the possibility that sometimes big changes follow from small events, and that sometimes these changes can happen very quickly.”[53] Information and messages that spread in this massive and disproportionate way must have specific properties. They must be infectious - to remain with the chosen imagery - not necessarily relevant yet interesting, and precisely for this reason of importance to many. They must definitely be comprehensible and they must permit connection with and within diverse worlds of experience. They must also encourage forwarding, retelling, and commenting, i.e. stimulate communicative processing that will again increase dissemination. However, if the new quality of the tipping point is finally to be reached, something more is needed. Malcolm Gladwell suggests in general terms something which is demonstrated in detail by the case of the successfully scandalised notebook vendor, namely: one or more connectors.[54]

Prominent connectors

They are agents on the Net and in the media, well-known and in the proper sense of the word optimally connected networkers. What they achieve by means of suggestions and recommendations, commentaries and reports, is to ennoble the topic under discussion, as it were, and to establish contacts between different groups, subcultures, and audiences in different networks due to their own multiple participation in all sorts of networks.

In the case of Amir Massoud Tofangsazan, the prominent mediators are primarily bloggers who link the site and inform other selected newsgroups, and journalists who play the role of central connectors. There is also a well-known newsletter that spreads the link to this site, and numerous forums discuss this revenge blog and refer to it.[55] A certain toto reports in the commentary area on Sawyer’s blog that he has posted photographs from the site together with a link to the blog in the seven - according to him - most active newsgroups. “This should generate some hits”, he writes. In addition, Wikipedia develops an extensive entry on Amir Massoud Tofangsazan. After a most instructive debate in which the principle of relevance is contrasted with the principle of interestingness, the entry is deleted by an administrator, but it may still be found on other sites.[56] If the web information service Alexa is to be believed, then even more than four years later links from a total of 231 websites will still lead to the blog of the Ebay revenger.[57] Apart from blogs, forums, and newsletters, the traditional mass media also function as prominent mediators and help to spread the information and break down barriers among the public - not without the powerful support of an interested Net community that addresses specifically selected potential multipliers. BeatPoet announces that the link will be sent to all national newspapers: “Wonder who’ll pick it up first?” And indeed numerous national and international media pick up the story, without however carrying out further investigations of their own; they simply reproduce the case without any further and more in-depth analysis. Only the British tabloid newspaper, the Daily Mail, deserves credit for giving Amir Massoud Tofangsazan a voice and, in fact, his very own voice.[58] Tofangsazan is quoted there with the following words: “I am shaking all over and I fear my reputation is going to be ruined.” The laptop was not damaged and he had nothing to do with the pornographic photographs or the images of women’s legs. “The last few days have been a nightmare, some of my friends have seen it and my father is very angry.” Tofangsazan’s father, Mohammad, tells the reporter of the Daily Mail that this story is extremely upsetting for the family.

The loss of proportion

For Thomas Sawyer himself all this is in no way cause for getting agitated but rather more a proof of his effective work, which he registers with satisfaction. With the help of ClustrMaps.com, the student with an obviously extremely high competence in media technology documents not only the number of visitors to his blog but also reconstructs their origins. The maps make clear that The Laptop I Sold on Ebay has achieved worldwide publicity. People on all continents visit the blog, most of them from Europe and North America. He clearly had not expected such an enormous wave of attention. “Wow”, he writes, visibly surprised in his blog, “this really is going swimmingly isn’t it?! I never could have imagined such a response. [...] anyway, I’m off to keep staring at the hit counter; I just can’t believe how popular this site is getting! Can we break the million?” In other commentaries he actively urges people to spread the link to his site, opens a PayPal account for donations, and places advertisements in his blog, which earn him about £900. It is illuminating, furthermore, that numerous commentators support his approach and method, although the dubious morality of this form of self-administered justice is obvious: the pilloried Amir Massoud Tofangsazan is given no opportunity to defend himself and to comment on the story from his point of view in some adequately organised procedure. The presumption of innocence is made to appear meaningless; the suspicion nourished by one single individual replaces proper evidence of guilt, the punishment by public defamation is executed without hearing the accused.[59]

Some of the numerous commentaries by supporters are occasionally downright euphoric as to what opportunities to cause public damage are revealed and demonstrated here. “Such sweet revenge! Laptopguy, you’re one clever bloke”, one can hear, for example, from RooRoo. Others try to heat up the emotional atmosphere. He has the hope, one commentator writes, who naturally wants to remain anonymous, that Amir will be deported with his family. As an alternative he wishes for the death or the suicide of the young man. “I hope the slimy bas*ard jumps in front of a bus so no one will ever have the misfortune to come into his presence again [...] Please Amir, Kill yourself”, he writes under the pseudonym Wazzer. In another mocking reaction we read: “Good luck with the plastic surgery and name change Amir.” Only very few of the intensively debating commentators on the website cautiously vote for a different view of things and pose the question whether the actual offence and the publicly executed punishment still stand in an adequate proportionate relationship.[60] So the voices do still exist, albeit only very few, that stress that here is a characteristic asymmetry of cause and effect. “I think that revenge should be equivalent to the offence”, one can read from qawsedrf. Some writers advise Sawyer to engage the police and the judiciary instead of administering self-justice. “The Internet is a very powerful instrument”, a contributor writes, “and it seems that many people use it for their personal interests on a global level that never existed before. What we have to learn as Internet users is that this power requires a profound awareness of responsibility on the part of the users.” For a moment even Thomas Sawyer develops doubts and reflects in one of his commentaries on the experience that he might very well have lost the control over his revenge campaign, that he was able to trigger this campaign but has now to admit that he had no power or ability to control and determine its effects. “I’m starting to think that this has gone far enough”, he writes and hints at stopping the revenge campaign in the digital universe. Yet nothing of this kind actually happens. The site is still online today although it has changed hands and the present proprietor uses his web presence to advertise self-brewed beer and cigarettes. However - luckily for the accused - the case has since lost in attractiveness. There are no new entries any more. The chase has ended.

1 Hondrich, Karl Otto (2002) Enthüllung und Entrüstung. Eine Phänomenologie des politischen Scandals [Disclosure and Outrage: A phenomenology of the political scandal], Frankfurt on the Main: Suhrkamp, p. 40.

2 Gross, Johannes (1965) Phänomenologie des Scandals [Phenomenology of the scandal]. In: Merkur, vol. 19, no. 205, p. 400.

3 Media victims, according to an illuminating definition, are all those who do not push into the media and live in self-determined anonymity - and who are nevertheless exposed against their will. See: Schertz, Christian/ Dominik Höch (2011) Privat war gestern. Wie Medien und Internet unsere Werte zerstören [Privacy Was Yesterday: How the media and the Internet destroy our values], Berlin: Ullstein, pp. 58f. On the business strategies of the popular newspapers see ibid. pp. 64ff.

4 Surowiecki, James (2005) The Wisdom of Crowds, New York: Anchor Books.

5 Le Bon, Gustave (2002/1895) The Crowd: A study of the popular mind, Mineola/New York: Dover Publications, pp. 6ff.

6 Anon. (2008) Drei Tage Staatstrauer in China [Three days of national mourning in China]. In: NZZ Online, 28 May 2008, http://www.nzz.ch/nachrichten/international/drei_tage_staatstrauer_in_china__1.736979.html (Retrieved 24 September 2013).

7 It is unlikely that the original video can still be found online. However, numerous copies of the film are accessible. See e.g. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bPDhZJmRB4A (Retrieved 27 September 2013). With English subtitles: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IeWRTcaXYNU (Retrieved 27 September 2013).

8 Groundbreaking on the processes of mob formation: Rheingold, Howard (2002) Smart Mobs: The next social revolution, Cambridge: Perseus Publishing.

9 Lin, Qiu (2008) Where angels and devils meet. In: Xinhua General News Service, 23 May 2008, http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2008-05/23/content_8237906.htm (Retrieved 23 September 2013).

10 http://comment.news.163.com/news_shehui6_bbs/4CGS78P900011229.html (Retrieved 23 May 2010).

11 Quoted from: Fletcher, Hannah (2008) Human flesh search engines: Chinese vigilantes that hunt victims on the Web. In: Times Online, 25 June 2008, http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/technology/article1858917.ece (Retrieved 10 July 2013).

12 Lin, Qiu (2008) Where angels and devils meet. In: Xinhua General News Service, 23 May 2008, http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2008-05/23/content_8237906.htm (Retrieved 23 September 2013).

13 Quoted from: Tan, Kenneth (2008) Online lynch mobs find second post-quake target: Liaoning girl detained by the police. In: Shanghaiist, 22 May 2008, http://shanghaiist.com/2008/05/22/online_lynch_mo.php (Retrieved 24 September 2013).

14 Quoted from: Tan, Kenneth (2008) Online lynch mobs find second post-quake target: Liaoning girl detained by the police. In: Shanghaiist, 22 May 2008, http://shanghaiist.com/2008/05/22/online_lynch_mo.php (Retrieved 24 September 2013).

15 The French magazine Le Tigre impressively demonstrated towards the end of 2008 how many items of information about an individual person can be spotted on the Net today, and how easily they can be put together with the help of search engines to form a comprehensive image of that individual. “Best wishes, Marc“, the magazine wrote in a letter published in one of its issues. “On 5 December 2008 you turn 29.“ The magazine reported numerous details from Marc’s life - from the name of an ex-lover to information about the last holiday in Canada with Helena and Jose. The irritating thing is: all this information could be found on the Net and was thus freely accessible. See: Meltz, Raphaël (2008) Marc L***. In: Le Tigre, November/December 2008, no. 28, pp. 36-37.

16 Feng, David (2008) The Chinese Web in action: Netizens of infamy. In: Shanghaiist, 28 May 2008, http://shanghaiist.com/2008/05/28/netizens-of-infamy.php (Retrieved 25 September 2013).

17 On the “search for human flesh“, see also: Sondermeyer, Juliane (2011) Clash of Cultures im Web 2.0. Der interkulturelle Scandal um Wang Qianyuan [Clash of Cultures in Web 2.0: The intercultural scandal around Wang Qianyuan], unpublished manuscript, pp. 18f.

18 Bureau of Democracy (2009) 2008 Human Rights Report: China (includes Tibet, Hong Kong, and Macau). In: U.S. Department of State, 25 February 2009, http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2008/eap/119037.htm (Retrieved 24 September 2013).

19 Duhr, Michaela (2008) Chinesen auf Menschenjagd [Chinese on the manhunt]. In: Netzeitung, 29 May 2008, http://www.netzeitung.de/politik/ausland/1033617.html (Retrieved 23 September 2013).

20 Lightman, Alex/Rachel Coleman (2009) Search (and destroy) engines. In: H+ Magazine, 02 June 2009, http://www.hplusmagazine.com/articles/politics/search-and-destroy-engines (Retrieved 24 September 2013).

21 On the triadic structure of the idea of causality (there is a cause, an effect, and a rule of transformation which changes the cause into the effect and the input into the output) see Foerster, Heinz von/Bernhard Poerksen (2002) Understanding Systems: Conversations on epistemology and ethics, New York/Heidelberg: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers/Carl-Auer-Systeme, pp. 46ff.

22 The authors would like to express their gratitude to Juliane Sondermeyer for manifold stimulating thoughts for this chapter and the exchanges concerning the case treated here.

23 Wang herself wrote the extensive report on the events: Wang, Grace (2008) The old man who lost his horse. In: China Digital Times, 11 May 2008, http://chinadigitaltimes.net/2008/05/grace-wang-the-old-man-who-lost-his-horse-video-added/ (Retrieved 26 September 2013).

24 On the worldwide protests against China’s Tibet politics and the extremely nationalist reactions of Chinese politicians at the time see: Lorenz, Andreas (2008) Engel im Rollstuhl [Angel in the wheelchair]. In: Der Spiegel, 28 April 2008, no 18, p. 122.

25 The letter can be read at the following Net address: Qianyuan, Wang (2008) Wang Qianyuan’s open letter. In: China Digital Times, 10 April 2008, http://chinadigitaltimes.net/wp-content/uploads/2008/04/grace-wang-english-ver-3.pdf (Retrieved 25 September 2013).

26 Wang, Grace (2008) My China, my Tibet: Caught in the middle, called a traitor. In: Washington Post, 20 April 2008. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/04/18/AR2008041802635.html (Retrieved 25 September 2013).

27 Suler, John (2004) The online disinhibition effect. In: CyberPsychology & Behaviour, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 321-326.

28 In most cases, Phillip W. Brunst explains, there is no real anonymity in forums, chats, blogs, and social networks, but rather pseudonymity, because the contributing participants can still be identified via their IP-addresses. Pseudonymity is therefore a felt anonymity, although utterances can - even if with some difficulty - be connected with a person. Anonymity, strictly speaking, entails that the unmasking of identity is impossible. See: Brunst, Phillip W. (2009) Anonymität im Internet. Rechtliche und tatsächliche Rahmenbedingungen. Zum Spannungsfeld zwischen einem Recht auf Anonymität bei der elektronischen Communication und den Möglichkeiten zur Identifizierung und Strafverfolgung [Anonymity on the Internet: Legal and factual frameworks. On the field of tensions between the right to anonymity in electronic communication and the possibilities of identification and criminal prosecution], Berlin: Duncker & Humblot.

29 See: Strittmatter, Kai (2008) Trainieren für Olympia. Die Menschenfleischsuche [Training for Olympia: The search for human flesh]. In: Sueddeutsche.de, 17 April 2008, http://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/trainieren-fuer-olympia-die-menschenfleischsuche-1.204850 (Retrieved 25 September 2013).

30 Thompson, John B. (2000) Political Scandal: Power and visibility in the media age, Cambridge: Polity Press, p. 15.

31 See: Wang, Grace (2008) My China, my Tibet: Caught in the middle, called a traitor. In: Washington Post, 20 April 2008, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/04/18/AR2008041802635.html (Retrieved 25 September 2013). Furthermore: Cha, Ariana Eunjung/Jill Drew (2008) New freedom, and peril, in online criticism of China. In: Washington Post, 17 April 2008, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/04/16/AR2008041603579.html (Retrieved 25 September 2013).

32 Dewan, Shaila (2008) Chinese student in U.S. is caught in confrontation. In: New York Times, 17 April 2008, http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/17/world/americas/17iht-17student.12081327.html?pagewanted=all (Retrieved 20 September 2013).

33 The logic of observing and the distinction between observations of the first and second order, underlying this conceptualisation, is described in the following book: Poerksen, Bernhard (2011) The Creation of Reality: A constructivist epistemology of journalism and journalism education, Exeter/ Charlottesville: Imprint Academic, pp. 24ff.

34 These reflections refer to the figure of thought outlined before, which hails back to Emile Durkheim. The confrontation with the outlandish, the immoral and scandalous, this father figure of modern sociology asserts, in the end allows for the re-enforcement of moral norms. It is an opportunity to make frontiers visible by crossing them.

35 Wang, Grace (2008) The old man who lost his horse. In: China Digital Times, 11 May 2008, http://chinadigitaltimes.net/2008/05/grace-wang-the-old-man-who-lost-his-horse-video-added/ (Retrieved 26 September 2013).

36 The following draws on a previous publication by Bernhard Poerksen and Wolfgang Krischke: Poerksen, Bernhard/Wolfgang Krischke (2010) Vorwort [Foreword]. In: Bernhard Poerksen/Wolfgang Krischke (eds.) Die Casting-Gesellschaft. Die Suche nach Aufmerksamkeit und das Tribunal der Medien [The Casting Society: The desire for attention and the tribunal of the media], Cologne: Herbert von Halem Verlag, pp. 7ff.

37 The question as to what colour the chameleon really assumes is unanswered. Detailed answers to this parable, which is most illuminating for theories of the media can be found in: Kelly, Kevin (1994) Out of Control: The new biology of machines, social systems, and the economic world, New York: Basic Books, pp. 69ff.

38 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hx_WKxqQF2o (Retrieved 06 March 2010).

39 Poerksen, Bernhard/Wolfgang Krischke (2010) Die Casting-Gesellschaft [The casting society]. In: Bernhard Poerksen/Wolfgang Krischke (eds.) Die Casting-Gesellschaft. Die Sucht nach Aufmerksamkeit und das Tribunal der Medien [The Casting Society: The desire for attention and the tribunal of the media], Cologne: Herbert von Halem Verlag, pp. 14ff.

40 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hx_WKxqQF2o (Retrieved 03 October 2011).

41 http://vids.myspace.com/index.cfm?fuseaction=vids.individual&videoid=32624312 (Retrieved 03 October 2011).

42 http://www.break.com/index/tricia-walsh-smith-crazy-divorce-woman.html (Retrieved 23 September 2013).

43 http://www.youtube.com/user/walshsmith1 (Retrieved 23 September 2013).

44 Quoted from: Gammell, Caroline (2008) “Callous” YouTube rant divorcee criticises £350,000 settlement. In: Telegraph.co.uk, 22 July 2008, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/2445563/Callous-YouTube-rant-divorcee-criticises-350000-settlement.html (Retrieved 23 September 2013).

45 Dreyer, Patricia (2008) Scheidungskrieg per YouTube. Richter kanzelt rachsüchtige Ehefrau ab [Divorce war via YouTube: Judge gives vengeful spouse a roasting]. In: Spiegel Online, 22 July 2008, http://www.spiegel.de/panorama/0,1518,567298,00.html (Retrieved 23 September 2013).

46 Schaertl, Marika (2008) “Fünf Millionen Dollar!“ Interview mit Tricia Walsh-Smith [“Five million dollars!” Interview with Tricia Walsh-Smith]. In: Focus.de, 21 July 2008, http://www.focus.de/kultur/leben/modernes-leben-fuenf-millionen-dollar_aid_319079.html (Retrieved 23 September 2013).

47 Eaton, Phoebe (2008) The YouTube divorcée. In: New York Magazine, 01 June 2009, http://nymag.com/news/features/47389/ (Retrieved 23 September 2013).

48 Amir (2006) The very bigging of the Amir Tofangsazan story. In: The Broken Laptop I Sold on Ebay, 08 May 2006, http://amirtofangsazan.blogspot.com/2006/05/jump-to-amirs-leg-zone-visit.html (Retrieved 25 September 2013).

49 This blog post is obviously a letter to Tofangsazan, although it was published under the pseudonym Amir:

Amir (2006): A message to Amir. In: The Broken Laptop I Sold on Ebay, 05 June 2006. http://amirtofangsazan.blogspot.com/2006/06/i-only-have-very-limited-Internet.html (Retrieved 25 September 2013).

50 Interview by the authors with Thomas Sawyer, 19 June 2010.

51 Corinth, Ernst (2006) Rache ist online [Revenge is online]. In: Telepolis, 01 June 2006, http://www.heise.de/tp/artikel/22/22797/1.html (Retrieved 23 September 2013).

52 http://amirtofangsazan.blogspot.com/2006/05/jump-to-amirs-leg-zone-visit.html (Retrieved 02 July 2010). A hit counter lists every visit to the website even though it may come under the same IP-address.

53 Gladwell, Malcolm (2001) The Tipping Point: How little things can make a big difference, New York/Boston: Little, Brown and Company/Back Bay Books, p. 11.

54 This concept is used by reference to Malcolm Gladwell’s concept of connector that denotes persons (outside the Internet). See: Gladwell, Malcolm (2001) The Tipping Point: How little things can make a big difference, New York/Boston: Little, Brown and Company/Back Bay Books, pp. 38ff.

55 See e.g. http://www.technofriends.de/thema-wie-ein-englischer-student-einen-Internet-gauner-blo%C3%9Fstellt-1948.html; http://www.p45.net/boards/showthread.php?t=82727; http://forums.macnn.com/89/macnn-lounge/296887/how-not-sell-broken-laptop-ebay/ (Retrieved 08 March 2010).

56 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amir_Tofangsazan (Retrieved 08 March 2010).

57 http://www.alexa.com/search?q=http%3A%2F%2Famirtofangsazan.blogspot.com%2F&r=site_screener&p=bigtop (Retrieved 08 March 2010).

58 Anon. (2006) Revenge of the Ebay customer sold “faulty” laptop. In: Daily Mail Online, 30 May 2006, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-388189/Revenge-eBay-customer-sold-faulty-laptop.html (Retrieved 28 September 2013).

59 See here also: Solove, Daniel J. (2007) The Future of Reputation: Gossip, rumor, and privacy on the Internet, New Haven/London: Yale University Press, p. 117.

60 Solove, Daniel J. (2007) The Future of Reputation: Gossip, rumor, and privacy on the Internet, New Haven/London: Yale University Press, p. 95.