IV. The New Technologies & the Opportunities of Ruthless Documentation

Anyone desiring to launch a proposal for outrage or trigger a scandal in this day and age has all the opportunities for doing so. The instruments are waiting to be used, the technologies are available. All that is needed is maybe a Smartphone, an unobtrusive digital camera, and access to the Internet for transmitting or posting the images and the audio clips, the videos, and the text files. It is not difficult to set up a blog or even a pillory site, to combine texts, photos, and videos. It is no problem to explain even more complex states of affairs and corroborate them with original documents. The available storage capacity for material data is theoretically infinite.

The instruments and the technologies for investigating norm violations, for documenting these comprehensively, and for finally publishing the resulting materials - with a possible worldwide echo - are within everybody’s reach. Search machines relieve everyone of the drudgery of on-the-spot investigations and facilitate comfortable ad-hoc research. Mobile phones, digital cameras, and voicemail services make the boundaries between the private and the public fuzzy. With their help, we can document and prove what has actually happened, and we can thus prop up even the most nebulous of suspicions with evidence that cannot be easily rejected. Occasionally, just one symbolically loaded image or just one crucial minute of a mobile phone video showing everything is sufficient. YouTube, blogs, forums, and personal websites may be used to publish materials and to distribute them. They can, whenever needed, also be used as bypass media, making it possible to circumvent and foil the orders of relevance of the gatekeepers and to grant personal perceptions of individuals a previously unknown publicity. Whatever one has done or somebody else has done or said may someday be transformed into data, documents, and thus potential evidence of scandals. Sometimes it is difficult to ward off the impression that we are dealing with zombie information because the data - in permanent storage - may not only be retrieved but updated at will, posted anew, recombined and revitalised in infinitely extended and repeated cycles. They can suddenly re-emerge and in their new contexts they can abruptly turn into proofs of scandals and documents of offences.

Digitalisation itself is the decisive factor here, changing scandal cultures worldwide. The Net philosopher Peter Glaser writes in the essay already quoted that “the transition to the digital aggregate leads, first of all, to a kind of highly reactive primeval soup composed of fragments and atomised cultural goods. It resembles the free radicals of chemistry that seek to combine in an aggressive manner.”[1] And as soon as there are freely circulating radicals they may possibly spread at great speed and finally be available in the form of infinitely re-combinable bits of data and items of information, as long as there is the hankering after scandalisation in at least a few people and as long as there is a public that is bent upon outrage. It must simply be acknowledged that data can now be more easily acquired, connected, transferred, reconstructed - and permanently stored - than ever before.[2] The extreme implication is that the distinction between past, present, and future evaporates and a new and simple plane of time emerges and remains, a strangely frozen present of enduring, eternal actuality.

1. The photographs of Abu Ghraib and modern eyewitness testimony

From simulation theory to reality shock

In January 1991 bombs were being dropped on Iraq, it was the time of the first Gulf war, a war that was advertised as a tightly focused surgical operation and a military action of extreme precision. One of the standard arguments advanced by prominent media theorists and image critics, at the time, consisted in the diagnosis of the disappearance of reality. The agony of what was conceived of as real was vociferously proclaimed, entailing the assertion that the very rush of the images, of the aseptic filmlets and the hectic twitching bombardment clips of the war, would obliterate the traditional distinction between reality and illusion. On the occasion of that war, the French philosopher and media theorist Jean Baudrillard granted an interview to two journalists of the leading German newsmagazine Der Spiegel. It still makes instructive reading today as a document of intellectual mischievousness and postmodern lightness of touch that would probably be fairly impossible to carry off in today’s age of pitiless documentation, and that would therefore appear utterly pathetic. Jean Baudrillard’s thesis in 1991 was that authentic reality representation had become impossible, that the media had replaced the indicative by the irrealis and that the mechanisms of appearance had installed their reign in a totalitarian way. Even the images of dead and injured people were no longer capable of unsettling the atmosphere of a great spectacle and an entertaining stage management; one could never be sure that the presented pictures of injured and dead people had not been manipulated by someone. Baudrillard: “In the realm of the images there are no [...] criteria for truth and falsity. We experience everything like a script. We are part of a great production.”[3] Right at the beginning of the interview, Baudrillard introduces the simulation theses that he has elaborated in many of his essays in a radically overstated form. He claims that it is not the media that turn the war into a virtual event - the war is not taking place at all. At the end of the interview, the two journalists ask him to comment on the rumour that he had been invited to join the war as a reporter in order to acquire first-hand experience on the ground. Baudrillard laughs at being confronted with this idea and says that he would not be suited for this kind of job. After all, he would “nourish” himself with the “virtual”[4] - a declaration of intellectual bankruptcy from a distance, which redefines the refusal to test hypotheses by primary personal experience as a philosophical position. The author Susan Sontag has sharply attacked this kind of “[f]ancy rhetoric” in her astute book Regarding the Pain of Others.[5] “To speak of reality becoming a spectacle”, she writes about Jean Baudrillard and related thinkers, appears to her to be “a breathtaking provincialism. It universalizes the viewing habits of a small, educated population living in the rich part of the world, where news has been converted into entertainment.”[6] And further: “It [this small population] assumes that everyone is a spectator. It suggests, perversely, unseriously, that there is no real suffering in the world.”[7]

It is of course questionable whether the followers of Jean Baudrillard would still be able to trade the same philosophical gags about the disappearance of reality and the non-existence of medially transmitted suffering with equal nonchalance today - and whether they would still find an audience via the newsmagazines of modern democratic states. The simulation theorists would not even have to leave the secure environment of their European universities today should they wish to check their diagnoses developed at a great distance by taking the risk of being emotionally affected by all the devastating counterexamples. According to their theory, they would not really have to go to war; they would not necessarily have to board a plane for Baghdad in order to stand face to face directly and personally with the cruelty practised there and to subject the news messages to the reality test. The immediate testimony of eyewitnesses would be superfluous because the effects of such eyewitness testimony can today be produced from a distance and in medialised form. To test their theses of simulation and stage management, Jean Baudrillard’s followers can now simply open their laptops and enter an address in their browser, e.g. http://www.salon.com/2006/03/14/introduction_2. They will find a survey and a catalogue of the emblematic images of the second Gulf war that would make any rash and overhasty self-distancing impossible even at such great distance. They would be able to see the torture photographs and the torture videos from the prison of Abu Ghraib, whose authentic quality cannot reasonably be doubted. Several thousand imprisoned Iraqis were interned in this prison at the end of 2003: real and alleged criminals, mentally ill individuals, men, women, and young people, people who happened to be at the wrong place at the wrong time during a raid or a spate of arrests. They were tortured pitilessly and sadistically due to the unconditional conviction that they had to be “boiled soft” - as was stated later in the investigation protocols - that they had to be destabilised by brute force so as to make them give away secrets in the ensuing interrogations.[8] It does not require prophetic gifts to see that the grand theses about deception and manipulation, the invocation of shows and spectacles, can only be rejected with horror in the light of such documents - or can only be maintained at the price of totally irresponsible dogmatism. The reality shock provoked by these images and videos is too massive; it would make any similarly sweeping talk about simulation appear as nothing but a cynical denunciation of knowledge.

Images and ciphers

The American Internet magazine Salon that had prepared and published the above quoted comprehensive documentation in 2006 provides its own statistic of the horror. Salon correspondent Mark Benjamin writes, with reference to an internal report, that there are 1,325 photographs of prisoner abuse, all taken between 18 October 2003 and 30 December 2003. Furthermore, there are 93 videos documenting the abuse, 660 pornographic pictures, 546 pictures of apparently dead prison inmates, 29 pictures of soldiers simulating or performing sexual acts, 20 pictures of a soldier with a swastika painted between his eyes. 37 pictures show military dogs used for intimidating prisoners. The photographs of slaughtered animals give a strange impression.[9] The Salon journalists decide on a selection of pictures that are judged to be acceptable to the public; they present it as “The Abu Ghraib files”. 279 photos and 19 videos are easily accessible by everyone. The editors have added reports to the “archive of horror” (Spiegel Online) that are kept in a deliberately factual tone, summarising the outcomes of the diverse court cases, diary notes by soldiers, and interrogation protocols, with a view to providing context and clear meaning to what is represented.[10]

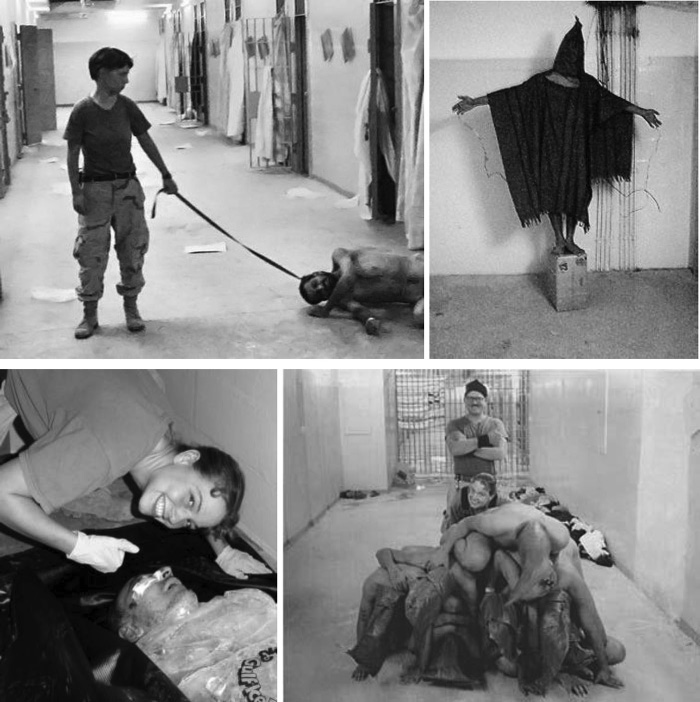

On these pictures, taken during weeks and months - their time codes allow the precise chronological reconstruction - one can see naked or largely unclothed prisoners who are kept tied to bedposts in unnatural and painfully dislocated body positions for hours and, furthermore, wear women’s pants on their heads - a method of humiliating Muslim men that was common everyday practice in the prison of Abu Ghraib. Some of the prisoners show injuries. Other prisoners are attacked by agitated dogs, worked up for the purpose, and bitten on their legs and genitals, and others again are heavily beaten up by guards with the utmost force. Some are obviously psychotic. On one of the photos, one recognises a man who has smeared his face and his body with sludge and excrement. Other pictures show an Iraqi who is beating his head bloody on the door - without being subjected to the use of force, it is said. One video documents that Iraqi prisoners are forced to masturbate in the group. Then there are, of course, also all those photographs that have entered the collective visual memory, photos that are bound to remove the last alibi for any mind that is still geared towards purposive ignorance and light-hearted escapist thought games.[11] These pictures are tangible evidence for the fact that an effective scandal is dependent on a relatively small number of rapidly retrievable images. These very images then become the symbols and the ciphers for the totality of the norm violations in question; they can evoke the events in a compact form provoking strong emotional reaction.[12] The photograph of the so-called “man in the hood” is possibly the best-known emblematic image of this kind from Abu Ghraib. It shows an Iraqi wearing a hood and a prison blanket like a poncho, standing on a small box and holding electric wires. Should he lose his balance and fall, the torturers threaten, he would execute himself with electric shocks. Another picture shows Private Lynndie England who has achieved dubious fame as the so-called “leash girl”. Lynndie England here leads a prisoner, nicknamed “Gus”, from his isolation cell with a belt slung around his neck, having him crawl on all fours across the bare floor. Another equally startling picture shows the pleasure obviously derived by the torturers from sadistic choreography and stage management. The photo, another emblem of the mercilessness of the American military, shows the entwined naked bodies of several prisoners piled upon each other to form a pyramid, with their torturers Charles Graner, Lynndie England, and Sabrina Harman posing for the camera with big smiles on their faces. The photograph of the so-called iceman that can also be found in the Salon collection documents a scandal that has not yet been properly redressed. It shows a still unidentified man, who was killed during an interrogation and whose dead body had to be kept for some time on a bed of ice in a shower room of the prison wing. As the melting ice water began to collect in front of the shower rooms, some of the soldiers working in this wing discovered the corpse; they even recalled hearing screams during the night without, however, worrying about them. They first examined his wounds and then photographed him. They removed the blindfold from the corpse in order to look at his face, which had been horribly disfigured by the heavy beatings. The crucial photograph shows the American Sabrina Harman bending over the dead body, grinning happily and triumphantly sticking her thumb up in the air. This picture, too, displays its characteristic power and dreadfully shocking impact because it short-circuits two contradictory spheres of meaning: the cruelty of torture and the mischievous cheerfulness of a young woman whose amusement is reminiscent of a holiday.

Figures 11 + 12 + 13 + 14: Emblematic images of the torture scandal of Abu Ghraib circulating worldwide: “the man on the leash”, “the human pyramid”, the so-called “man with the hood”, and the “iceman”.

The self-fabricated panopticon

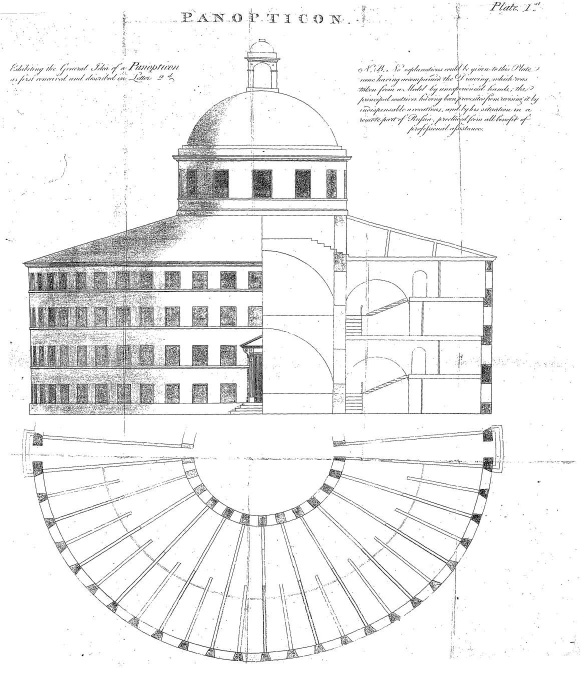

It is one of the topoi of image-critical analysis in connection with the work of the French philosopher Michel Foucault to refer to the thought model of the panopticon of the philosopher Jeremy Bentham developed at the end of the eighteenth century.[13] Bentham’s aim was to perfect the surveillance of prison inmates. He therefore conceived of a circular prison building with all the single cells arranged around its centre in the pattern of a fan. This design permitted the guards and other staff to observe every single inmate from an inspection house in the centre without being seen themselves. The inmates are aware of this state of potentially total visibility although they cannot possibly know whether they are actually observed in every moment of their imprisonment. They consequently adapt their behaviour correspondingly, so the theory implies. They internalise the idea of potential control and allow themselves to be disciplined accordingly; and they behave as if they were actually observed all the time simply because this might indeed be the case.

If the thought model by Jeremy Bentham is made the basis for an analysis of the torture pictures in the present digital age, a fundamental change becomes apparent that has to do with the relationship between guards and guarded, between observers and observed. The omnipresent digital media have become and are still becoming ever smaller and ever more powerful, cameras, mobile phones, and video cameras in particular. They make it possible (independently of the personal goals of the agents) to interchange roles and perspectives in a radical way. Observers are suddenly observed themselves, guards likewise guarded, and prison warders become prisoners by virtue of their very lust for documentation that manoeuvres them into the prison while forgetting that the pictures and film sequences they produce might one day jeopardise their very existence.

Figure 15: The drawing of Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon - from the centre of the building, every single cell may be inspected.

They observe themselves as well as others, but are unaware of the possible consequences of their being observed and without taking into account the mobility of data and documents in the digital age.[15] This form of mental innocence and naïveté counteracting anticipation in a self-fabricated panopticon can be shown up compellingly by the concrete examples under discussion. The procedures and motives of those who fabricated the pictures and videos in Abu Ghraib have meanwhile been analysed in detail. A special, in parts apologetic, film about the torture photographers (Standard Operating Procedure) is in its entirety available on the Net. A book based on this film has been published. It reconstructs the history of the origins of these modern icons of horror without, however, reprinting a single picture. It exclusively follows the perspective of those perpetrators who were later taken to court and who make up a core group consisting of only a few of the persons shown in the pictures. Only these few are sentenced to imprisonment, by the way - an illuminating detail, again demonstrating the power of images. All the many others who must have been involved, for instance in the torturing and killing of the “iceman”, who have attended to wounds, transported injured persons, and bullied other prisoners, got off scot-free. No pictures of these persons exist that could be made public. Personnel of the CIA or the Defence Intelligence Service are not prosecuted, anyway. Put succinctly, this means: each one of the torture photographs highlights one single specific moment of aggression - but the overwhelming impact of these photographs masks and conceals a hidden subsidiary world of unobserved crimes and events.

The medium of blameless participation

The reservist Jeremy Sivits, who took the picture of the human pyramid, is amongst those who are prosecuted in a court of law. His punishment consists in one year in jail and a dishonourable discharge from the army. The American private Lynndie England took several pictures - and can be seen in them. In one of them she leads a prisoner, who is forced to crawl on the ground, from his cell with a belt around his neck, thus visually documenting an archetypal scene of brutal, sexually connoted dominance.[16] In another one, she is shown laughing and pointing at the genitals of prisoners who are forced to masturbate. Then she photographs fellow soldiers without a flash so that they remain unaware of being photographed. She finally gets a prison sentence of three years and becomes, as is reported, the “face of Abu Ghraib”.[17] The Rolling Stones sing about her; she is parodied in an episode of The Simpsons. She becomes the personification of the torture scandal. The example of Lynndie England shows that a scandal always needs concrete persons, culpable individuals that can be held responsible for their actions, because they could have acted differently and could have chosen alternatives.[18] Portraits and interviews in big magazines have been upsetting people because they made quite clear that Lynndie England did not recognise and accept her own responsibility, that she did not feel any remorse for what she did, that she shrugged off the pain and suffering of the torture victims and much rather considered herself as a victim of unfair deception. It is a common procedure of rejecting guilt by subjects of scandalisation to re-define their actions as externally determined events and their former power as factual powerlessness due to appalling circumstances and oppressive forces.[19] Many pictures were taken by specialist Sabrina Harman, a military police woman from Maryland, with a traditional digital camera. She was also the one who laughingly bent over the disfigured face of the killed “iceman”, triumphantly sticking up her thumb in her rubber glove. Her sentence: six months in prison. Staff sergeant Ivan Frederick - sentenced to eight and a half years in prison - had his picture taken sitting on an Iraqi detainee. He also admitted tying the electric cables to the hands of the so-called “man in the hood” and to having threatened him with lethal electric shocks; in addition, he admitted forcing prisoners to masturbate.[20]

He can be seen with a camera in his hands in a picture of the man in the hood, whose horribly helpless suffering reminds some observers of the image of the crucified Christ. This is most instructive because the act of taking a photograph is obviously seen as granting the persons with cameras a particular form of justification and a sort of moralising rationalisation of what they are doing. Taking up the camera thus obviously allows the perpetrators a (fictitious) change of role and an act of briefly distancing themselves - allowing them, furthermore, to suppress rising scruples. In some of their letters and statements the torturers give the impression that they understand the camera - perhaps only in some semi-aware way and manner - as a medium of blameless participation, as an instrument of distance-creating documentation. The camera is supposed to relieve its user subjects of their role and responsibility for what is happening: its users are only recording what is happening, they are only agents of transmission, and not active aggressive perpetrators of crimes.[21] Even Charles Graner, the leading performer of crimes, who was sentenced to ten years in prison, occasionally justified his actions towards Lynndie England with the statement that somebody had after all to document the events in Abu Ghraib in as credible as possible a way. War veterans would need documentary evidence for traumatising experiences after their return home, for the purposes of free therapy and adequate treatment, without which they might perhaps be ignored and rebuffed. A large number of photographs, namely 173 of the 279 pictures published by Salon.com, were taken with his Sony FD Mavica. And it was he who spread the photographs showing the tortures. Graner boasted about them, copied them on CDs, passed them on to acquaintances in his unit, showed them openly to his superiors and to higher-ranking military persons who had no objections - and so actually used his camera as an instrument for the documentation of his own crimes. His brutal treatment of the prisoners is described in an interview by the Iraqi Mohanded Juma Juma, which was first published by the Washington Post and is still accessible online. “They stripped me from my clothes”, he said, “and all the stuff that they gave me and I spent 6 days in that situation. [...] Approximately at 2 at night, the door opened and Graner was there. He cuffed my hands behind my back and he cuffed my feet and he took me to the shower room. When they finished interrogating me, the female interrogator left. And then Graner and another man, who looked like Graner but doesn’t have glasses, and has a thin moustache, and he was young and tall, came into the room. They threw pepper on my face and the beating started. This went on for a half hour. And then he started beating me with the chair until the chair was broken. After that they started choking me. At that time I thought I was going to die, but it’s a miracle I lived. And then they started beating me again. They concentrated on beating me in my heart until they got tired from beating me. They took a little break and then they started kicking me very hard with their feet until I passed out. In the second scene at the night shift, I saw a new guard that wears glasses and has a red face. He charged his pistol and pointed it at a lot of the prisoners to threaten them with it. I saw things no one would see, they are amazing. They come in the morning shift with two prisoners and they were father and son. They were both naked. They put them in front of each other and they counted 1, 2, 3, and then removed the bags from their heads. When the son saw his father naked he was crying. He was crying because of seeing his father. And then at night, Graner used to throw the food into the toilet and said ‚’go take it and eat it’. And I saw also in Room #5 they brought the dogs. Graner brought the dogs and they bit him in the right and left leg. He was from Iran and they started beating him up in the main hallway of the prison.”[22]

These are the moments and scenes that Graner records on photographs in order to save them from oblivion and to keep them for a global public to view at a later date. Paradoxically, he evidently does not really know himself what he is photographing when he is taking his pictures.[23] He has no idea that the pictures will forever connect him with the horrors of torture, will make him a hate figure as soon as they are placed in a different, in a new context. He is constantly at the centre of the excesses of violence and loves to present himself in the pose of a victorious conqueror. He can be watched beating prisoners, his hands protected by rubber gloves against the blood of the maltreated, he can be seen sewing up the wounds of tortured persons or holding down a prisoner on a stretcher like an animal killed in a hunt.

The uncanny clone

The pictures essentially document - apart from the substantial violence - a semantic universe in its own right, a peculiar world of meaning of its own. In this world, superiors right up to the American Minister of Defence, Donald Rumsfeld, and the President George W. Bush, promote the humiliations, possibly even recommend them, and certainly tolerate them. Thus they provide a fundamental and not totally implausible pattern of self-justification for the perpetrators on the grounds that there had been different pronouncements by the American leadership that made the prohibition of torture appear more or less obsolete.[24] In this other world, torture is perhaps not completely legal but in any case legitimate, and those who are made to suffer are not accepted as human beings with equal rights but are defined as aggressors and terrorist warriors. They are a menace, and not an equal opponent that deserves a minimum of respect. In this other world, pictures of violence can be made more attractive by adding sexual humiliation carried out allegedly for the preparatory purpose of optimally effective interrogation, but perhaps also in order to furnish the pictures circulating amongst the comrade soldiers with additional stimulation and kicks. But this self-created semantic universe, this specific reality of torturers and photographers, only exists for a select public. This peculiar reality must be sealed off in precisely determined ways in order to control information. This undertaking is, however, doomed to fail for a double reason. For one, the material has become extremely mobile, it can easily be copied and transferred, stored and archived independently of any locality. Furthermore, it is passed on in the most breathtakingly sloppy way and in no way treated with the scrupulous care it requires. When the then Staff Sergeant Joseph Darby returns to Abu Ghraib from a family holiday, he is told that he has missed a bloody shoot-out but that it has been preserved on film.[25] He asks Charles Graner for information and is given two randomly picked CDs that, however, do not contain the expected pictures of the mentioned shoot-outs but the torture photographs that will soon circulate round the world. Presumably, he was given the torture images by mistake or simply because of the characteristic negligence that illustrates how secure and safe everybody felt that the crimes committed would be understood as something normal, that the semantic universe would not really be taken to be something obscene, bizarre, or just downright criminal.[26] Darby copies both CDs and returns them to Graner. At first, he cannot classify and contextualise the images. But as soon as he recognises on a photograph his fellow servicemen behind the “human pyramid”, he realises that the pictured scenes have been played out in the prison and therefore in his very own personal world. He understands that he is not looking at some perverse joke amongst American soldiers but at the humiliation and torturing of prisoners. After some hesitation - well aware of the potential consequences of such a betrayal, particularly the possible bullying - he decides to inform his superiors, who start investigations in January 2004 and, as far as one knows, immediately inform the US Minister of Defence, Donald Rumsfeld, and soon after also the American President.

In the prison itself, a hectic search for other pictures begins; questionnaires are distributed. For a short time amnesty boxes for questionable material are set up, probably not even, and possibly not even primarily, with the intention of carrying out a more thorough investigation and examination, but mainly with the purpose of securing as many pictures as possible in order to contain the damage and prevent the further spreading of discrediting material.[27] Even the relatives of soldiers who are living in the USA are contacted and asked for pictures that might have reached them via e-mail from Iraq. It is as yet not known who passed the torture documents to the media but the final collapse of the semantic universe of Charles Graner and his collaborators can be pinned to an exact date: 20 April 2004. On this day the US television station CBS shows the first pictures from the whistle-blower that travel around the world within days and produce an outcry of indignation. The reputation of the US is damaged immensely because the official justification of the Iraq war - consisting not only in the search for weapons of mass destruction but also in the removal from power of the dictator Saddam Hussein and the securing of human and freedom rights - is here blown to bits before the eyes of the world. High-ranking military personnel, the Minister of Defence, Donald Rumsfeld, and the Secretary of State, Condoleezza Rice, offer their apologies. The American President, George W. Bush, has himself quoted with the statement that he had never ordered torture.

At this point in time, the pictures have long become ubiquitous and have become the codes of a reality that can no longer be denied. They can be found in the marketplaces of Iraq. Enlarged to poster size, they are stuck to the walls of houses, they are passed from hand to hand in photo albums, they are spread as e-mail attachments, stored on CDs[28] - and they naturally provoke horrible forms of retaliation as well as images of revenge and counter-images of immense cruelty.[29] Even caricaturists and artists take up the by now worldwide available motifs. The silhouette of the man in the hood, according to the art historian W.J.T. Mitchell, changes into an “uncanny clone“, a symbol of public remembrance, which remains intelligible even in the context of a parodying advertisement.[30] Only a single example must suffice here to show this method of creative estrangement and explicit violation of context. One day anonymous activists in New York distribute the image of a silhouette placed against a monochrome background, thus reminding observers of the iPod dancer and the corresponding advertising campaign by Apple. This time, however, the dancer stands on a small black box - and he has a hood on his head, wires in his hands, a poncho draped round his body. The Apple logo has been substituted with a bomb and instead of “iPod” it now says “iRaq”.

However, these forms of an aesthetic and inevitably somewhat light-hearted variant of the accusation do not succeed in establishing themselves as new emblematic images because they are simply not strong enough to approximate let alone surpass the shock effect of the original photographs. But it is still instructive that the dramatic original images obviously produce their impact much more directly than anything that is written. And the images are, furthermore, not open to contradiction in a comparable way.

Figure 16: The fusion of two iconic images - the so-called “man in the hood” and the iPod dancer.

That images may outdo words and texts, that visual signs may prevail over linguistic signs and may even surpass them with instant persuasive power, is endorsed by the fact that the crimes in Abu Ghraib had already become known in December 2003 through a note smuggled out of the prison. However, Iraqi lawyers had raised questions as to the trustworthiness of what was described. In the note from the prison, a woman reported that several female prisoners had been raped by American prison warders and were now pregnant. She asked Iraqi resistance groups to bomb the prison in order to spare the inmates further shame. The correctness of her allegations was confirmed officially after an internal investigation. However, the report of the desperate woman - lacking as it did any documentary image - did not trigger equally shocked reactions amongst the public, and even amongst the essentially sympathetic lawyers scepticism prevailed. By contrast, photographs still seem to guarantee reality and truth. They are not assertions that can easily be denied and explained away but pieces of evidence that can stand on their own - although they do require linguistic explication.[31]

From the authenticity of the material to the reliability of the source

Nevertheless, the ascription of unqualified authority to photographic images may appear surprising because a long-lasting debate, not only within academic circles, has been concerned with the loss of authority of the documentary image, a debate that has in fact been aiming at the destruction of its quality as evidence and its aura of pure and immediate factuality. The central argument is the following, to put it briefly: a photograph is a paradoxical construct of subjectivity presenting itself pseudo-objectively, pretending to be realistic appearance and authentic staging. The reasons are simple: a photograph can be edited with little effort and faked without trace, particularly with currently available image processing software tools.[32] In addition, any photograph inevitably incorporates a particular perspective. It therefore cannot claim to be a representative section of the world because it systematically obscures a huge and tremendously multi-faceted residual reality. The crucial question is then whether this undoubted fact makes it impossible to trust the torture photographs of Abu Ghraib. Do they lose their evidential force; is their authority reduced by such a general suspicion of their having been stage-managed? This is not at all the case, as all the reactions to the visual material show. A review of the publications and reflections on the power of images with regard to the Abu Ghraib case yields the following results: there is no criticism of images and stage management. All too massive is the overwhelming impression of reality, all too shocking and obscene the content of the documents. Pure naked horror prevails. There is no comment from the simulation theorists; no disciples of the philosopher Jean Baudrillard can bring themselves to test the master’s theses about the agony of what is conceived of as real in a confrontation with the freely floating material from Abu Ghraib. Only Tony Blair, the former British Prime Minister, is said to have voiced the assessment that the images could not possibly be genuine. But his view remains the exception. Why? What features of the material and its communicative context could possibly block the common ad-hoc doubts and the fundamental suspicion of stage management (a well-tested defence strategy to ward off guilt)? Or to pose the question differently: what are the reasons that make the impression of authenticity and truth irrepressible? The first and material-related answer is that the photos and videos exhibit their very own aesthetics of authenticity. This aesthetics of authenticity, however, consists in its anti-aesthetics - this is the decisive paradox. Each one of the pictures lacks the trappings of perfection and that is the reason why they appear so genuine, so real.

It is more than obvious that the cameras were not worked by professionals. The photographs have turned out blurry and smudgy, the persons are badly caught, their faces are frequently truncated, and the scenes are only dimly lit. The second and context-related answer is that in the digital age the photographic document no longer carries evidential force because it is too easily manipulated. The trustworthiness of the source of images and the authority of the persons and institutions reacting to the publication of the images have since become the decisive kind of qualifying meta-information. In the present case, the reactions of the American government and the statements by Donald Rumsfeld, Condoleezza Rice, and George W. Bush - the public apologies, the proclamation of disgust, the insistent assertions not to have known anything about the situation in the prison of Abu Ghraib - have certified the genuineness of the material in a derivative way, as it were, and thus reinforced its evidential force. And even the finally sentenced perpetrators were and are, of course, particularly credible witnesses for the prosecution. Photographs and films have made innumerable human beings in the whole world eyewitnesses of a crime. Consequently, it is not the images themselves that still outrage and shock today; it is, quite tangibly, quite directly, the reality of what they show.

2. The camera phone film from Hong Kong and the mobile phone as an all-purpose weapon

The triumphant advance of an indiscrete technology

Hong Kong is one of the places in this world that is teeming with mobile phones. For every thousand inhabitants there are 899 mobile phone contracts; adding prepaid cards raises the number to 1712. This means that many people living in this Asian metropolis use more than one mobile phone. The majority of these mobile phones are, as is now customary with many models, fitted with a camera. Mobile phones have long ceased - universally by now - to be a status symbol or a plaything for elites; they have become integrated in everyday communication. They are used for appointments and the writing and sending of e-mails and short messages (via SMS or WhatsApp), they serve to record the normality of people’s lives, to shoot photographs of things and events to remember, to make wacky videos, to manage addresses, to access Facebook, Twitter, or YouTube, and to listen to music. And they can also be used as multipurpose weapons of scandalisation, and can thus be understood, in the true sense of the word, as a mass medium that defies the traditional constellation of surveillance - only a few powerful people observe a large number of comparatively powerless people - with “total surveillance from below”.[33] Mobile phones can be used unobtrusively to document actual or alleged norm violations committed by other people and to make these documents accessible to an interested public on suitable platforms. And this very thing happened in the case of the unemployed Hong Kong man Roger Chan Yuet-tung, who has since become known worldwide under the name Bus Uncle.[34] His story exemplifies a kind of communication that vacillates between genuine outrage and quirky fascination. Without the mobile phone and without the globally growing lust for mutual observation it would certainly never have taken off.[35]

Everything starts on the evening of 27 or maybe 29 April 2006 - nobody really knows when exactly because the dates and references in circulation vary. At about 23.00h, 51-year-old Roger Chan Yuet-tung is travelling on the double-decker express bus 68X in Hong Kong in the direction of the Yuen Long district, where his home is - all this is held to be correct - and he keeps speaking on his phone in a very loud voice the whole time. A passenger sitting behind him, later identified as Elvis Alvin Ho, feels disturbed, taps Chan on the shoulder and asks him to lower his voice.[36] In doing so, he uses the Cantonese word for uncle, which in Hong Kong is a polite way of addressing older men. Despite this, Chan throws a tantrum and begins to berate the 23-year-old real estate agent. “Why did you tap on my shoulder?” he wants to know from Ho. “I’ve just been speaking on the phone.” Ho reacts in a conciliatory manner, but this makes Chan even angrier. “I don’t know you. And you don’t know me. So why are you doing this?”, he furiously questions him, turning back and bending over the seat to face Ho, his finger stopping only a few centimetres away from Ho’s face. The elderly man in his white shirt repeatedly challenges him to apologise. When Ho does so, however, Chan still cannot stop. He goes on screaming that the quarrel has not been resolved. Six minutes his outburst of anger lasts, for six minutes he screams at Ho without intermission, while Ho remains sitting there in a strikingly relaxed manner, his arm lazily stretched over the back rest of his seat. This posture fuels Chan’s rage even more. “I am under pressure, you are under pressure. Why are you provoking me?”, he wants to know. Swear words fly, Chan reviles Ho’s mother, roars vulgar insults through the speeding bus - until his mobile phone starts ringing again. He mumbles “Blast!”, turns away and starts talking on the phone again.

Figure 17: Roger Chan Yuet-tung’s angry outburst in a Hong Kong night bus - recorded by a mobile phone camera.

Chan and Ho have no idea, simply do not realise that another passenger, Jon Fong, accountant and student of psychology, is filming Chan’s tantrum and his tirades from the other side of the aisle. He is using his mobile phone as an indiscrete technology - in the precise wording of the sociologist Geoff Cooper - as an instrument of effective scandalisation, as it is globally omnipresent nowadays.[37] 4.6 billion people own a mobile phone, a 2010 estimate says. More than a billion handsets are fitted with a camera function, a technology that lends its users the power to function as amateur reporters, spies, or evidence gathering witnesses.[38] It blurs the differences between once strictly separated spheres of communication, between the private and the public spheres, backstage and front region, everyday world and working world - as here illustrated by the story of the Bus Uncle in Hong Kong. Only two days after the encounter on the bus, the then 21-year-old Jon Fong publishes the pixelated camera phone video on YouTube under the pseudonym sjfgjj, without however naming the two performing central agents.[39] It is his hobby, he says later. And he wanted to save the material in case the two men started to fight and hit each other.

The camera phone film as evidence of a scandal: the downfall of John Galliano

It is not a question of rumours and assumptions but of certainties. Camera phone films and their own peculiar anti-aesthetics increasingly function as providers of evidence of scandals, evidence that is viewed as particularly authentic. A prominent example is the Dior designer John Galliano. He had to leave his job because in December 2010 (and shortly afterwards again), drunk in a Paris café, he had screamed anti-Semitic tirades - and was filmed by a camera phone on at least one of these occasions. On a video that is accessible on the Net a voice from behind the scene asks him: “Are you blond, with blue eyes?” He replies: “No, but I love Hitler.” And he goes on: “And people like you would be dead today. Your mothers, your forefathers, would be... gassed and... dead.” When the British tabloid newspaper The Sun published the video online, his career with the renowned fashion house was over, and everybody hastened to explain that racism and anti-Semitism would not be tolerated under any circumstances. His sudden downfall illustrates the power of an indiscreet but omnipresent technology that can destroy an image within the shortest conceivable span of time.

Hype around a marginal piece

However, the video is not only watched by a few of Fong’s friends and acquaintances. It turns into a YouTube hit and thus becomes an example of how an essentially unimportant incident can be scandalised by a single individual and consequently, thanks to the concentrated power of Web 2.0, develop into an event and a curious Internet meme that attracts worldwide attention. The very banal and infinitely trivial content of the story throws into sharp relief the formal features that tend to shore up an excess of global attention or at least render it likely. In May 2006, the video had already become one of the favourite viewings on the platform. It continued to gain in importance because of a self-reinforcing mechanism of attention grabbing, a ranking principle, whose essential feature is to reward achieved attention with even greater attention. It is an all too well-known phenomenon that books ranking high on a list of bestsellers sell even better simply for that reason alone. The same applies to hit lists on their corresponding Net platforms. YouTube (loading an average 48 hours of video material every single minute) automatically computes rankings and recommends videos by their viewing frequency, thus obviously in turn attracting even more viewers to the high-ranked films. The reception career of Bus Uncle can no longer be reconstructed in precise detail. An author of the news agency Associated Press sees the film in position 2 in this month,[40] other sources claim it had made it to position 1.[41] Be that as it may, the fact is that the video - the meme - has reached millions of people within an extremely short time - and that, due to the process of permanent feedback, more and more people have increasingly become interested in Chan.

Memes

Memes are units of information that diffuse through a culture and a public, keep seeping continually, are often endlessly varied and copied, but essentially retain their identity. According to the inventor of the concept, sociobiologist Richard Dawkins, memes may consist in a single slogan or sentence, a song line or an entire song, an idea, a religious concept, a whole ideology or weltanschauung. Images and even distinct film sequences may become memes and populate our world of imagination, possibly ousting other concepts. This age of the Net has seen the renaissance of the doctrine of memetics, itself now a meme.

About three weeks after the upload, 1.2 million hits are registered, a week later 1.9 million. By the end of June 2011 the video lists nearly 4.1 million hits. Users rate it 3,968 times, 4,322 visitors store it amongst their favourites. As there are numerous copies on YouTube and other platforms, it is impossible to establish the total number of hits. The number for all the circulating copies of the film is supposed to have already reached 5.9 million on 29 May 2006, one month after the upload of the original video.[42] How many millions of viewers have clicked it since then up to the present day remains unclear. Obviously, the subtitles in English and in Mandarin have been of decisive importance for the international circulation and the global impact of that outburst of anger. Even viewers not fluent in Cantonese can thus understand the content of the dialogues and the expressions of defamation and the video can, consequently, cross the language barrier and reach its enormous audiences. The subtitled copies are also clicked several million times. By the end of September 2013 the two most popular Bus Uncle videos with bilingual subtitles list about 4.1 million hits.[43] The comments on YouTube make clear how enthusiastically the users are reacting to the video. “Hahahahahahaha, so funny!!!!!!!”, DonLi utters, for example. There is a particularly intensive debate on who is actually to blame for Chan’s angry outburst. Opinions differ widely, showing characteristic battles for opinions and interpretations in a public that articulates itself uninhibitedly but with freely discharged aggression, clamouring for the validity of its own positions without any previous tests of relevancy by gatekeepers. What has in fact happened, how should it be assessed? The majority of commentators criticises Chan and his behaviour. Some even think that the norm violation is a particularly grave one and demands the public pillory. “Oh man”, we read, “this type is crazy [...]. He has the worst behaviour in the world, he is ridiculous.” Many of the comments are extremely aggressive. One - obviously anonymous - hoyun writes: “Damn it, every time I watch this video I would like to hit this old man.” Some comments are directed at Ho. “In my opinion, this guy has behaved like a dirty swine. You can see how impertinent he was when the uncle threw his tantrum”, writes highcontrast. Others call Ho a coward. He should have fought with Chan, several users demand.

The observer’s blind spot

It is interesting to note that, despite the diversity of the reactions, all the comments are directed exclusively at the people performing in the film. Fong’s behaviour - the secret filming and the upload of the video - is rarely questioned or made a topic of discussion. This reflects a general pattern, a normal and typical narrowing of vision that shifts the observer and the discloser of an event into a blind spot. The question is no longer what he has actually done when bringing his camera phone into position, when he took on the role of a self-created norm police and made no attempt to mediate and pacify but instead mulishly concentrated on his filming - and also whether one would like to live in a world of possible total transparency.[44] The public takes the final video product for granted, without investigating the story of its origins and development, without analysing the way and manner of its publication and without, in the extreme case, scandalising the procedure itself.

It is also striking (though not typical) that the hits continue to increase and the number of video viewings keeps rising. Instead of reporting massively on the mobile video and debating it for a few days or weeks, both Internet users and the traditional media deal actively with different aspects of the incident for nearly three years. Then, finally, stagnation sets in, only then the public apparently turns its attention to other topics. The questions immediately arising are now: Why? What is so captivating about such an unimportant norm violation? How is the stabilisation of such an inherently fragile kind of attention achieved? A first and rather generally formulated answer is: the absolute prerequisite in any event is new stimuli. Furthermore, there is a possibility of constantly updating and modifying interests and enthusiasm by transforming the original seriousness of the outburst of anger into a more or less cheerful game with public participation. In this way, the original medially fixated content might at the very least be given a new form; it could, for instance be parodied and alienated. This kind of ironical-creative processing of the material obeys a central commandment, orients itself by a fundamental requirement that must be met if the attention of the public is to be retained. It is first of all necessary to offer something new, something extraordinary and unconventional. Secondly, what is offered must remain comprehensible and connectible at all costs so as to avoid frightening the public away with merely warped and hermetic incomprehensibility. The special challenge is to find a schema, a recollection, on the one hand, and to break and frustrate it in a comprehensible and perhaps even exhilarating way, on the other, in order to produce a kind of stimulation surplus. This kind of communicative balancing act can be captured in a tentative formula in the following way: vary what is known in such a way as to turn it into something unknown; but still allow the unknown to be recognised as something known.

Remixing and resampling

In this very understanding of playful variation creating new stimuli for reception, for instance by parodying and alienating what has long been known in an inspiring way, some YouTube users soon generate manifold mash-ups of the video. They fabricate collages and recombinations of images and sounds, data and video sequences, which set the core event of the tantrum into ever new, ever different contexts. There is, for example, a Star Wars version of the key scene, in which Chan and Ho fight with lightsabers, or a Taxi Driver variant. A rap song combines the most popular utterances in the quarrel between Chan and Ho with a song of the Hong Kong singer Sammi Cheng, and a karaoke remix invites listeners to join in a sing along. The upshot is: according to research published in the Asian Journal of Communication, all in all 127 different mash-ups of the Bus Uncle film have appeared on YouTube between 29 April 2006 and 18 June 2007.[45] In this timespan alone, the video inspired 77 users to react to the original film with one or more creations of their own. The majority of the variants and variations consist in remix versions with popular music (37.9%), but there are also completely novel, creative products by YouTube users (the study just mentioned quotes a share of 22.7%). Some of the mash-ups (9.8%) connect the original recordings with excerpts from films. Most of the video replies exhibit a joking and sarcastic undertone; there is no serious commentary at this stage.[46]

The traditional media, curiously enough, adopt a special role. Local and regional media are the first to report; they even instigate a regular chase for the central performers, going so far as to offer financial rewards for their detection. This kind of local-regional reporting carries on for weeks on end. When the quarry Bus Uncle is finally spotted and presented in diverse exclusive interviews, he is transformed into a public personality. For this reason, it is now obviously a subject of general interest that he is offered a job by a steakhouse chain. And it is indeed an international news agency that distributes the news message that three masked nameless persons turn up at his new workplace and beat him up so badly that he has to be taken to hospital.[47]

However, it is not just the artistic-creative mash-ups, it is not just the medially driven chase or the sudden attack on the neo-celebrity Chan that keeps the interest in place. Certain supplementary events are staged with the intention of completing the dramaturgical script and injecting a little more tension into what is happening. Therefore, a media enterprise arranges a meeting of the protagonists. A group of journalists persuades Chan (allegedly for money) to pay his former antagonist Ho a visit at his firm in Mongkok in order to apologise for his behaviour and to offer him the business proposal of a “Bus Uncle Rave Party”. Ho, however, throws the group out of his office and complains not to have been informed beforehand. At the end of May, the case finally creates an international stir. First of all, a message from the news agency Associated Press is published that triggers a spate of articles.[48] But this is no longer mere news reporting on the case; the incident is analysed and reinterpreted as a symptom - and it therefore again increases in value having thus been furnished with intellectually more demanding elements and interpretations. “’Bus Uncle’ is cinéma vérité”, the Washington Post columnist Eugene Robinson writes, for example. “It’s amazing that in nanoseconds, a slice of Hong Kong life can be experienced in Washington, Johannesburg or Moscow.”[49] Often in these reports the question is posed as to whether there may be some deeper meaning somewhere in his vulgar actions, or that his outburst of anger could perhaps be understood as a significant event in the sense of a diagnosis of the times. “Chan’s phrases”, writes Marianne Bray of CNN, for instance, “reflect the pressure that comes from living in a city where 6.9 million people are squeezed into 1,104 square kilometers [...] of land.”[50]

Democratisation of celebrity

Repeatedly other YouTube videos are compared with the Bus Uncle video; there is suddenly a Police Uncle, a Train Uncle, or a Bus Auntie. In other words: the case has set up a peculiar schema of observation in its own right and has made Chan a celebrity that is famous for no other reason than for being famous. His ad-hoc career provides extensive illustrating material for the generally noticeable democratisation of celebrity. “The control of attention and importance is no longer available to only a few professionals”, the diagnosis runs, “but it is potentially and at least in the perception of many free for all.”[51] Now, there are the traditional stars that have acquired their status through professional work, competence, and a carefully cultivated image. They are bathed in an “aura of inaccessibility”.[52] But, as the present example shows, there is also an increasing number of people who present themselves publicly, who have acquired no competence or are not in any way singled out by an interest-arousing social position (high office, famous name).[53] They have no secrets, no special aura, no specific talent, but they generate fascination because they have more or less accidentally stumbled or been pushed into the garish light of publicity. They generally behave without social skills and therefore occasionally evoke - as representative figures of a mass public without professional qualities - sympathy, but also gloating and envy. Their central and striking commonality is simply to have somehow become medially conspicuous at the right point in time and to have aroused public interest, although it cannot easily be established what their particular skills are and how the butterfly effects of attention-creation function in detail. This radical separation of prominence and competence also characterises Chan, whose real achievement is his secretly recorded tantrum - the initial spark setting off his media and celebrity career absolved in record time. As soon as he is famous and notorious, the traditional mechanisms of the celebrity business kick into action and increase his publicity according to the fundamental principle of the so-called Matthew effect: unto every one that hath shall be given.[54] Or put differently: publicity enhances publicity. Interviews with Chan are published that are elevated to the rank of lead stories. He is nominated by a public service radio station in Hong Kong for the election to Man of the Year 2006; and he makes it to second position just barely failing to reach the top position! Collaborators of Wikipedia produce entries on this incident that are since available in Cantonese, English, French, and Swedish. Fan articles have begun to circulate. An online shop in the USA sells T-shirts, teddy bears, and also handbags with an engraved Chan head. Boxer shorts and buttons with translations of Bus Uncle statements are also to be had, also mobile ringtones for download with the best-known quotations that have become proverbial in Hong Kong (“I am under pressure. You are under pressure.”). In brief: the story of the night bus in Hong Kong, the scandal that was never a scandal at all and was nevertheless treated as such by an enthused public, lives on and has turned its protagonist into a Net celebrity, a star of the new age. Entering the expression Bus Uncle in Google in English or Cantonese, thus enacting a modern proof of existence, will still generate an enormous quantity of hits - even after several years. To be precise, the number of hits today as these lines are being written is 64,700.

3. The calamitous e-mail and the easiness of misfortune

Change of modes of communication

Innumerable e-mails are sent every day. In most cases, the electronic mail reaches the intended addressee. From time to time, an e-mail happens to end up with the wrong recipient - which is usually of no great further consequence. Often such a message is ignored; occasionally its sender is informed. However, selecting the wrong mail address, i.e. the wrong recipients, for one’s mail may cause extremely embarrassing effects. Sometimes a single mouse click proves to be a serious error because it suddenly and unexpectedly creates totally unwanted publicity, the effects of which cannot be negated despite immense effort. One moment of inattentiveness suffices. On 22 June 2006, at 09.43h, 21-year-old Susanne Klauser sends her first e-mail of the day, “Morning slice!”, to her colleague Tina Braun[55] - both at work for the German Federal Labour Agency - and receives the reply “Hey Baby, everything okay?” at 09.44h. “Am just sort of tired and have earache. Fred came last night for three quarters of an hour. Had shaved specially! And then he didn’t want me. No sex for practically two weeks. Well, nothing doing. How was your evening then??” An animated dialogue about most intimate affairs unfolds between the two women. Ten e-mails whizz back and forth, quickly adding up to a sizeable collection of texts. And then Susanne Klauser inadvertently mistypes her friend’s e-mail address before sending message number eleven, and at 12.01h sends the whole accumulated package of e-mails to the central mailing list of her department - triggering an extremely “juicy affair” (Bild newspaper).

The story is illuminating not so much for the content it confers but because it provides the opportunity of a detailed examination of the changes in modes of communication and the stepwise expansion of a communicative circuit. At the beginning, the two women obviously practise a highly private one-to-one communication, the status of which, however, is fragile and strangely porous due to the peculiar character of the medium. A single typing error, not spotted in time, will immediately integrate other addressees. An e-mail program will usually make ad-hoc suggestions of possible recipients, anyway, as soon as the first few letters are being typed in. Furthermore, any sent e-mail can be forwarded to other persons at lightning speed. In the case of the two women, the unfortunate sending of the e-mails to all the addressees on the department’s mailing list is first followed by a phase of some-to-some communication, still taking place within the narrowly circumscribed circle of colleagues. E-mail publicity still remains restricted to a fairly limited kind of public whose members all know each other and work together. Eventually, however, the packet of e-mails reaches the Internet and, in a last phase of the dissemination process, the popular press and other mass media. This momentous change of the communicative circuit now lends the story potential reputation-damaging explosiveness. In this phase, different modes of communication are united. On the one hand, the mass media follow the classic one-to-many logic; the Net, on the other hand, functions also according to the principle of many-to-many communication, in practice primarily on a regional and local, but potentially also on a global, scale. The different phases of dissemination can now be precisely reconstructed. The colleagues are the first to be informed promptly and comprehensively about the sex and love lives of the two young women. Soon afterwards, the mails spread quasi-epidemically and at great speed, they are forwarded, copied, linked, commented on, and finally even translated. It is possible that one of the women’s colleagues - allegedly one Andreas Schmidt, as is maintained by a blogger with the name of Woodstock - sends the mails to friends and acquaintances for fun and amusement, who in turn spread them further afield, and so on and so forth. In this way, the mails reach other, ever new and ever larger communicative circuits - they actually transmute into a sort of digital chain letter, multiplying according to the principle of the snowball effect. Names and e-mail addresses of people who make intimate communication accessible to an amused, gloating, and outraged public are often retained in a long list preceding the correspondence and may therefore easily be spotted. So it becomes clear once again: the act of publication and distribution is of marginal interest to the Net community; it is not considered an action worthy of criticism nor is it considered necessary to delete its traces. The ruling idea is that the messenger is absolutely innocent.

The spectrum of reactions

The intimate correspondence can be found on many sites of the Net, in most cases even carrying the proper names of the women. Bloggers report on it, copy the text to their sites, or offer it for downloading. On the platform Scripd, a German version is made available online together with a version in English, in order to increase and accelerate its further distribution. Its success is unspectacular, however, and certainly not global. In numerous forums users set links to the downloaded texts or copy them into threads, chains of consecutively arranged postings of messages and commentaries. Finally, the traditional mass media, in particular the popular gutter press, discover the story. The reporting there is largely driven and coloured by schadenfreude - and the two women are only scantily anonymised. Here is one exemplary quote from the newspaper Berliner Kurier: “Now there is only one thing left for the two gossip chicks: bag on the head and forward. Or emigrate. Faaaaar away...”[56] Only Spiegel Online manages a year later to present an analysis of the case with the necessary depth. One can read there, for instance: “Never before could a single human being have found so much fame with a gigantic public in such a short span of time - and never before could a person have plummeted so low from such a height.”[57]

What are the consequences of such massive attention? What motives may be exposed, what reaction patterns established? To clarify these questions it is worthwhile looking at the numerous comments offered by people in forums, in blog posts, or in attachments to the continually spreading mail. Here one can discover a broad spectrum of opinions and forms of reaction. One group is outraged, another gloats, and a third group shows recognisable voyeuristic interests in the contents. Some discuss the genuineness of the correspondence, others prefer an analysis, some voice sympathy, and a few prophesy the two women a media career.[58] The suggestion that the e-mails could have been composed during their working time produces indignation. “Such intimate things have no place at work. [...] the question for me now is whether they do not have enough work to do at the FLA”, one of the commentators asks angrily. Numerous outraged reactions are provoked by the language of the mails. “In what kind of trash language are they talking to each other?!”, one Prusse-Liese asks who herself does not display a quite perfect sense of style, either, and Simon remarks: “They surely do not need particular linguistic abilities for their jobs!” Many users think, moreover, that the incident simply confirms the bad reputation of the FLA: “Extrapolate from these dumb office clucks to the totality of the FLA employees, then one can only draw the consequence that one’s application papers are better directed anywhere else than to this kind of institution!” NoHartz demands the dismissal of the two women: “Stupidity must be punished, and that can only mean and will hopefully mean in this case that the two dim-witted frusties are fired right away!” A very widely shown reaction is schadenfreude. There are numerous comments like the following: “I can’t contain myself ha ha ha ha!” Another user adds the following subject heading to the e-mail forwarded by him: “Guys, this is pure embarrassment... the joke of the month!” The voyeurs, no fewer in numbers, naturally react to the intimate revelations with salacious notes, for example: “I would very much like to get to know those two. They would be satisfied and relaxed in no time!” Blood titles his blog post on the case with the line: “Horny pussies at the FLA.”

The evidence is now: anonymity causes inhibitions to crumble. Repeatedly, a fraction of the sceptics raises the question as to whether the dialogue can really have taken place in the documented form. “I think that this is a fake (silly season)!”, writes Goldelse - like numerous other discussants who share the same opinion. Others reject this view; they do not believe in a hoax. “Definitively no fake. Have a friend in the FLA, and she told me last night via SMS that they are no longer allowed to go online at work”, communicates one Ciccio. Quite apart from all these diverse outraged, obscene, and sceptical comments, one can discover a few that show a kind of analytical-reflective character. In one blog the case is said to illustrate “the far reaching influence of modern means of communication” because it shows that the Internet can destroy lives. “Barely 15 years ago such an outcome would have been unthinkable and very difficult to achieve.” User Uwe concludes that some employees were given an e-mail crash course free of charge by the incident. He warns: “E-mails are electronic postcards! Write nothing in a mail that you would not write on a postcard!” Only very few voice their compassion with the victims and show empathy. A small number of users predict unexpected riches to come from the undesired attention, a career as talk show guests and advertising stars: “Millionaire at a stroke through TV presence, and then advertising money.” Nothing of this sort actually happens. The consequences for the two women involved are largely negative. “We are constantly being goggled at, and people are whispering about us behind our backs”,[59] an online medium quotes Susanne Klauser. It is alleged that the incident cost the colleague who forwarded the e-mail his job. It is also alleged that one of the women has since moved to Bavaria to take a job in a bank. It is alleged that after the publication of the éclat about the two women all the employees of the FLA have been forbidden to write private e-mails during their working hours. The truth in all this is impossible to ascertain in detail. Suggestions, assumptions, and rumours abound. One thing is, however, certain - despite all the questions about truth and factuality, the documentation of a calamitous typing error in the summer of 2006 as well as the identity of the two women can still be researched and established today without major difficulty. Communication intended for the moment is all but transitory. The digital stigma remains. There is no chance of its deletion. It will stay, unchanged.

4. The tell-tale SMS and the economy of morality

From rumour to evidence

An SMS is the medial instrument of relaxed focusing. It enforces condensation. Whoever writes SMSs comes right down to brass tacks and, as a rule, formulates in ways that do not obey the demands of standard language or written communication. An SMS is congealed purpose-driven orality, easily produced, but potentially secured for duration. The medial form itself provokes the representation of what is private; it favours the presentation of contents and intimacies which could potentially be used as evidence of norm violations in other contexts. In new contexts, SMSs could thus rise to the status of written documents thereby losing the character of trivial sensationalism or ephemeral utterances whose reality content might be subject to controversial debate. SMSs are, as a rule, directed at a defined addressee. They are ad-hoc messages stored on the mobile phones of the sender and the recipient. Due to their hybrid status, they tend to provoke a potentially risky oblivious disregard of the medium. This disregard of the medium - the lacking sense of the conditions of its exploitation and the actual properties of the medium used - is illustrated by the diverse scandals and affairs that owe their particular explosiveness precisely to the SMS as evidence.[60] Whoever texts in quick succession tends to overlook all too easily that the activity creates pieces of writing that may survive the moment, that the texts may not necessarily be formulated for the moment only but in fact constitute written records that will continue to exist unless they are deliberately deleted. These texts can, once torn from the original context of their intended use, become documents of defamation and demolition. They have the capacity to support flimsy rumours with definitive proof. They can, once published, endanger world stars and billion dollar industries - as is shown by the story of Tiger Woods, golfing star with a nice guy image and the first self-made billionaire in the history of sport, icon of a market ultimately dependent on his decent behaviour and the intact stage management of his public existence.

The first news item threatening the idyllic PR world, the first indication that there was something wrong with Tiger Woods, derives from an event in the early hours of 27 November 2009.[61] At 02.25h the golfer crashes his Cadillac Escalade first into a fire hydrant only a few metres from his house in Florida and then into a nearby tree. His wife Elin Nordegren smashes the tail window of the car with a golf club to rescue her husband who had lost consciousness, she later tells the police. She claims to have helped in an accident, but her story fails to convince a great number of the media that favour the description of the event as an eruption of marital violence. A few days later, on 2 December 2009, the American magazine US Weekly publishes the confessions of the waitress Jaimee Grubbs. They provide the decisive trigger for a spate of reports running for months about a plethora of affairs. The story is now run under the title Tigergate. Grubbs explains that she had had a 31-month long affair with Tiger Woods. The proof: 300 SMS messages, many of which can subsequently be read on the Net and on websites of popular mass media. They are erotically allusive short dialogues quoted in many media and blogs, brief statements with the sole purpose of ascertaining mutual availability and sexual readiness.[62] They give the British columnist Alexander Chancellor cause for pessimistic laments in an essay that is of fundamental interest to media theory. In his essay dealing with love letters by the “romantic lecher” John F. Kennedy he compares and contrasts the gently courting love letters that Kennedy wrote by hand and sent by post to the Swedish woman Gunilla with the sex SMSs by Tiger Woods that are geared towards the quick satisfaction of his wants, alerting his playmates and urging them to send him nude photos. Chancellor writes: “But mobile phones must be partly to blame for the chilling nature of contemporary mating rituals. It is as difficult to be oafish in a handwritten letter as it is to be romantic in a text message. Letters are for keeping and re-reading. Text messages are for getting to the point in the speediest and most direct way possible. Some people who have assumed that text messages are discarded as fast as they are written are now finding to their cost that this is not necessarily so.”[63] Alexander Chancellor describes the shift from the invocation of nuances to the crude command, the transformation of the desired counterparts from adored subject into objects serving only one purpose. Handwritten letters and SMSs are for him metaphors for particular relationships between the personal self and the outside world.

Be that as it may. It is not just the SMS messages - disqualified as stylistically inferior - that show up and disgrace Tiger Woods. It is in particular a message from the voicemail of the mobile phone of Jaimee Grubbs that appears on the Net. Everybody who cares can listen to it. In it, Tiger Woods requests her to delete her name on her voicemail intro as quickly as possible because the contact data of his mobile phone have fallen into the hands of his wife and she might possibly ring all the numbers including hers (Grubbs’). Grubbs does indeed delete her name, she insists. However, she does not cooperate further in any way in the desperate attempts of Tiger Woods to obliterate the traces of their relationship. On the contrary, she dances through talk shows, offers interviews, poses for erotic photos, and apologises in a sentimentally staged television programme to the betrayed wife in order to stabilise the sudden peak of attention. The declaration of remorse serves only as a scant legitimation and merely apparent moral justification of further public appearances as well as the excesses of the follow-up reporting during which new intimate details are spread out.

Gradually, many other affairs are made public. Other women follow the example of Jaimee Grubbs; in retrospect, one could say that she had set the standard and the style. The porn star Joslyn James publishes infinitely more crudely formulated intimate SMS messages, speaks about the details of the sexual encounters with Tiger Woods. “I can only imagine the pain she’s feeling now, and I’m sorry”, divulges the model Cori Rist in the US television programme Today - once more a staged declaration of remorse. Photographs of diverse lovers appear. Some of these lovers arrange press conferences or appear on the radio. Fantastic numbers begin to circulate, including stories and claims that elude assessment. Ever new purported or actual lovers emerge who try very hard to market their confessions by reporting alleged erotic predilections and shared parties - handing over any available material to the popular mass media and the aggressively-operating, chequebook-swinging gossip portals like TMZ.com - all labouring systematically to exploit the scandal as thoroughly as possible.[64]

The dramaturgy of the public confession