Yummy…Fact Families!

If you’re like a lot of kids, then you prefer your sandwiches plain—no goopy mustard or anything else with a weird texture, thank you very much! Just plain bread and plain turkey, perhaps? Or ham? Or maybe you’re a cheese-sandwich type, like Mr. Mouse? In any case, I’ll use turkey for our example because it’s my favorite and you can’t stop me. (Just try.)

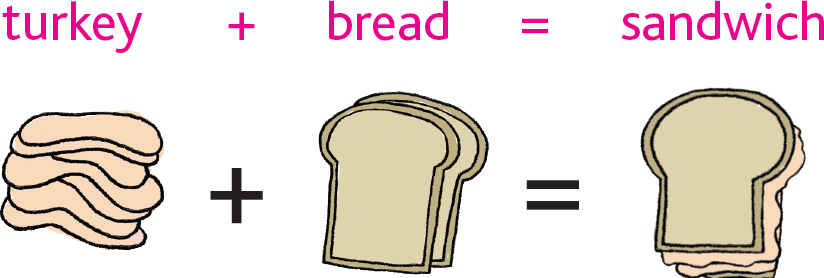

We’ll add some turkey to some sliced bread, and lookie, we get a sandwich! Yep, that’s a fact.

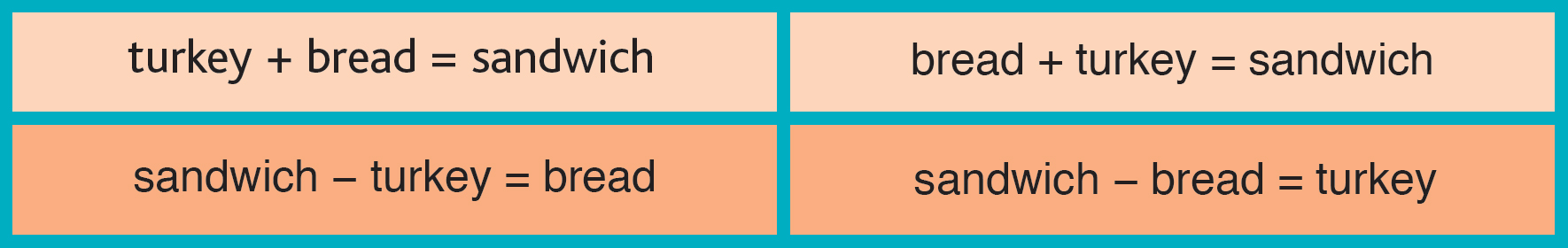

We could write this fact as a “sandwich sentence”:

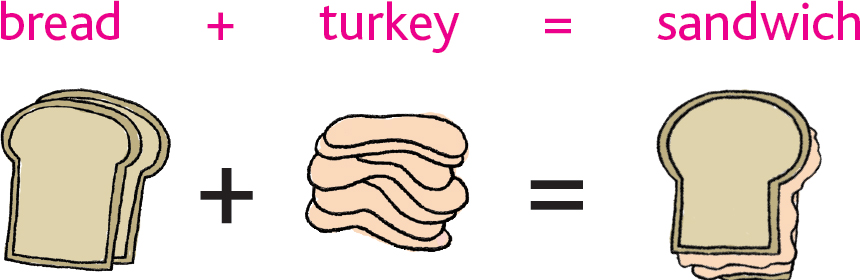

I guess we also could have written:

And that’s another fact. Well, it’s sort of the same fact—they’re saying the same thing, after all!

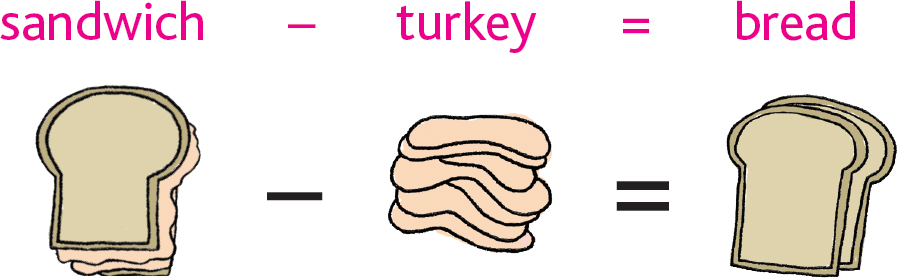

Okay, but what if we wanted to take apart the sandwich? I mean, if we took the turkey off, would we still have a sandwich? Nope! We’d just be left with the bread.

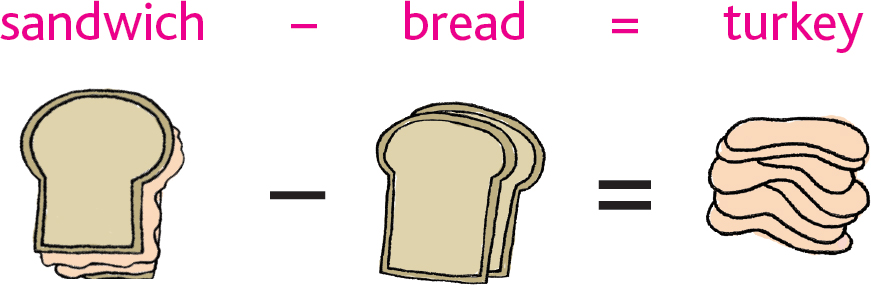

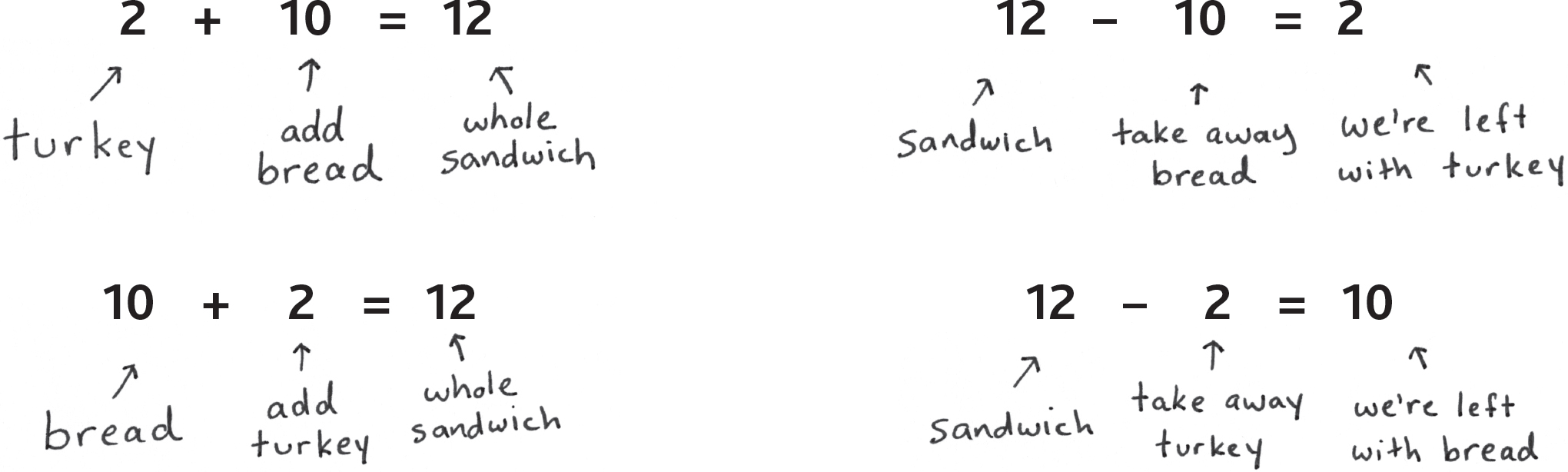

See what we did there? We had a sandwich, then we took away (or subtracted) the turkey, and we ended up with bread! And that’s another fact, isn’t it? What if instead we started off with a sandwich and we took away the bread? What would we be left with? Yep! Just the turkey! That “sandwich sentence” looks like this:

Yet another fact. We’ve now created four facts out of the same three things—all of these facts are related to each other. So we could call this a fact family, you see?

And we can make fact families out of math sentences, too!

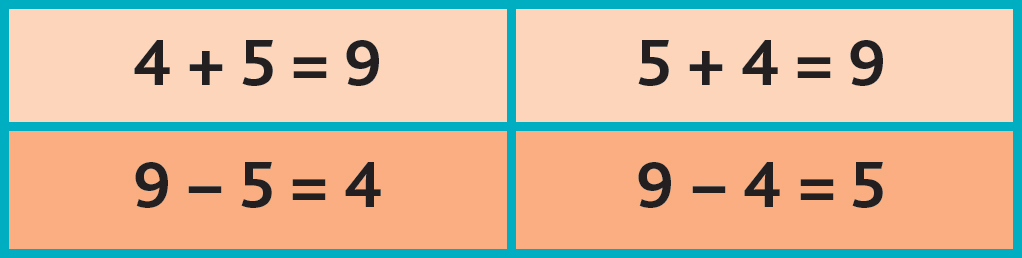

A fact family for addition and subtraction is a group of addition and subtraction facts that all use the same numbers! For example:

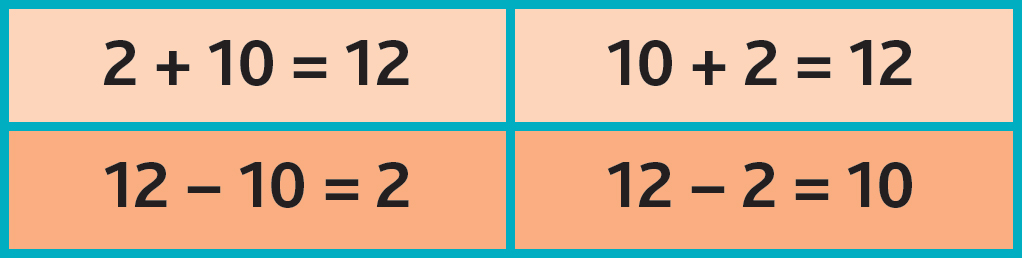

The subtraction sentences start with the biggest number. Makes sense, right? We have to start with the whole sandwich before we can destroy it. Here’s another fact family:

And here’s how this fact family would look in terms of sandwiches. Easy, right?

Lunch Boxes: Part-Part-Whole!

Can you imagine just carrying around your sandwich, apple, and water in your arms at school all day? A lunch box sure is a lot easier, right?

When it comes to fact families, a box can make things easier, too….

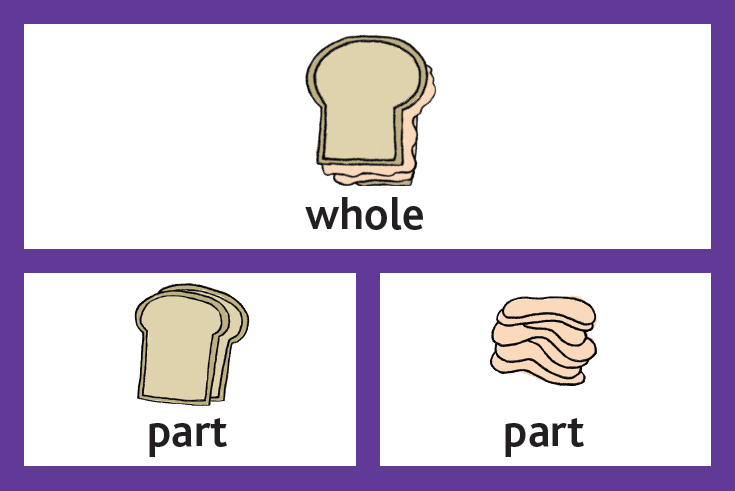

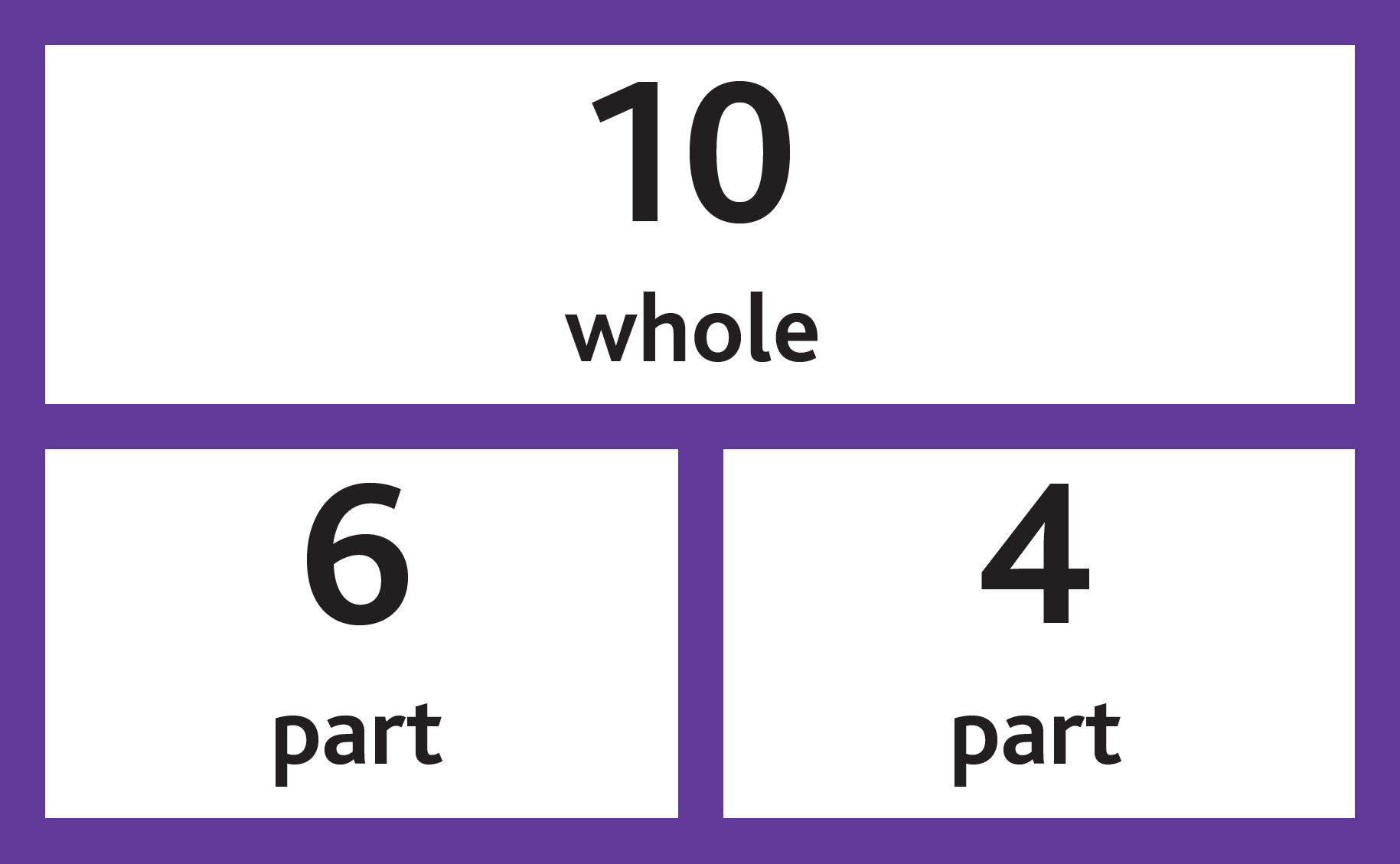

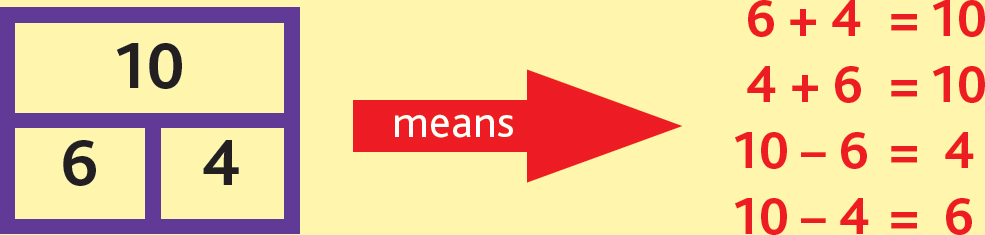

Some people call these part-part-whole boxes, since the two parts (of the sandwich) add up to the whole (sandwich). It still means the four math sentences—it’s just a much shorter way to write it!

Many textbooks now say there are eight facts in a fact family, not four—all they are doing is rewriting the same four facts, but putting the answer in front. In this case, we’d include 10 = 6 + 4, 10 = 4 + 6, 4 = 10 – 6, and 6 = 10 – 4. Seems like a lot of extra writing to me, but do whatever your teachers ask you to do (or they might get mad at me)!

A part-part-whole box uses three numbers to show a fact family. The biggest number goes in the biggest box, and the two numbers that add up to it go in the smaller boxes. Together, they stand for an entire fact family. For example:

Sometimes the “whole” will be on top with the “parts” underneath, and sometimes the “whole” will be on the bottom with the “parts” on top. But the biggest number—the “whole”—will always be in the biggest box!

It’s just two ways of writing the same thing!

In any case, it’s all really just sandwiches. And remember, the biggest number is always the whole sandwich.