In the previous chapters, we admired the many fascinating relationships that were created by inspecting triangles and the points, lines, and circles that are related to them. In this chapter, we will focus on the many common and surprising areas created by triangles and their lines, points, and circles. Triangle areas or their portions hold many fascinating surprises, which we will discover as we journey through this chapter.

Appropriately, we shall begin by first establishing ways in which we can find the area of a triangle. From the most primitive basis, we would begin by considering the area of a square and then the area of a rectangle—that is, if possible by just counting the number of square units they contain, or just multiplying the length by the width. We then progress to the right triangle, which can be seen as half of a rectangle. In figure 7-1, we notice that the right triangle ABC is half the area of rectangle ABCD. This allows us to state that the area of a right triangle is one-half the product of its legs. Here, in figure 7-1, AreaΔABC =  ab.

ab.

As we consider the area of a general triangle, we can separate it into two right triangles as shown in figure 7-2. (By “general triangle” we refer to a randomly drawn triangle of no particular shape or property other than being a triangle.) Here we can find the area of each of the two right triangles that compose the given general triangle and then add them to get the area of the complete general triangle, which leads us to the well-known formula for the area of a triangle: one-half the product of a base and the altitude drawn to that base.

In figure 7-2, the sum of the areas of the two right triangles (ΔADB + ΔADC) is  . However, a + b is the base of the general triangle; therefore, the area of triangle ABC is

. However, a + b is the base of the general triangle; therefore, the area of triangle ABC is  (altitude · base).

(altitude · base).

An analogous development of the formula can be made for an obtuse triangle as shown in figure 7-3.

Here we consider the areas of two overlapping right triangles: triangle ADC and triangle ADB. The area of triangle ABC is equal to the area of triangle ADC minus the area of triangle ADB. Therefore,

We are not always given such convenient triangle parts to find its area. There may be times when we will be given only the length of two sides of a triangle and the measure of the included angle, as shown in figure 7-4. In this case, we will engage some trigonometry to help us develop a formula to find the area of the triangle. We just established that the area of triangle ABC =  hb. In right triangle BCD, we have sin γ =

hb. In right triangle BCD, we have sin γ =  , or h = a sin γ. By substituting this value for h into the previously established area formula, we get Area ΔABC =

, or h = a sin γ. By substituting this value for h into the previously established area formula, we get Area ΔABC =  (α in γ). b =

(α in γ). b =  ab sin γ, which gives us yet another formula for the area of a triangle.

ab sin γ, which gives us yet another formula for the area of a triangle.

Were we to have been given the lengths of two sides of a triangle and the measure of an angle not included between these two sides, we would not have been able to determine a unique triangle, and hence would be unable to get a definitive area. With such given information, the triangle could be obtuse or acute, thus not allowing us to determine the area of the triangle—since it could be either one of two triangles—each with a different area. We show such a case in figure 7-5, where triangle ABC and triangle ABC′ have two pairs of corresponding sides equal, and a pair of corresponding angles (∠A) equal—ones not included between these sides in each of the two triangles. Obviously, they have different areas, as one triangle is acute and the other is obtuse.

COMPARING THE AREAS OF TRIANGLES

The formula Area ΔABC =  ab sin γ leads us to a rather unusual way to compare the areas of two triangles that have a pair of corresponding angles equal. Namely, the ratio of the areas of two triangles, having an angle of equal measure, equals the ratio of the products of the two adjacent sides. So that in figure 7-6, where ∠B = ∠E = β, we have

ab sin γ leads us to a rather unusual way to compare the areas of two triangles that have a pair of corresponding angles equal. Namely, the ratio of the areas of two triangles, having an angle of equal measure, equals the ratio of the products of the two adjacent sides. So that in figure 7-6, where ∠B = ∠E = β, we have

It should be clear that two triangles that have the same lengths of their respective base and altitude have equal areas. Also, two triangles that have the product of their altitude and base the same also have the same area. Furthermore, if two triangles have two sides that have equal products and the angles included between these two sides are equal, then, again, the triangles have equal areas.

Now here is a nice and less well-known relationship: The ratio of the areas of two triangles inscribed in equal circles equals the ratio of the product of their three sides. To justify this bold claim, we first have to consider another triangle relationship, which we show in figure 7-7, where triangle ABC is inscribed in a circle with diameter AD, and the altitude to side BC is AE. Then we claim that AB · AC = AD · AE.

This can be shown by noting that, since angle B and angle D are both inscribed in the same arc, they are equal. Since triangle ACD is inscribed in a semicircle, it is a right triangle. Thus the right triangles AEB and ACD are similar, and thus  , or AB ⋅ AC = AD ⋅ AE.

, or AB ⋅ AC = AD ⋅ AE.

We are now ready to justify the comparison of triangle areas mentioned above, namely, that the ratio of the areas of two triangles inscribed in equal circles equals the ratio of the product of their three sides. For figure 7-8, where the two circumscribed circles are equal (each with diameter d), we would then want to conclude that

From the previously demonstrated relationship, we have b ⋅ c = AE ⋅ d, and q ⋅ r = PT ⋅ d.

Therefore,  and

and  Thus,

Thus,  , which can be rewritten as

, which can be rewritten as

We are now ready to compare the areas of the two triangles:

We know that when we are given the lengths of the three sides of a triangle, a unique triangle is determined. Therefore, in such a case we should be able to establish the area of the triangle. Heron of Alexandria (ca. 10–ca. 70 CE) developed a nifty formula to enable us to find the area of a triangle when the only information that we are given about a triangle is the lengths of its sides. This formula for the area of triangle ABC (figure 7-9) is

AreaΔABC = , where

, where  , which is the semiperimeter of the triangle.

, which is the semiperimeter of the triangle.

The development of this formula is provided in the appendix. Applying this formula is quite simple. For practice, we shall apply it to a triangle whose sides have lengths 13, 14, and 15 units long, which then has a semiperimeter of 21. Thus, with Heron's formula, we get the area of the triangle as

There are lots of other formulas for finding the area of a triangle, each requiring the measure of various parts of the triangle. We offer just some of these triangle-area formulas here (referring to figure 7-10):

There are also area formulas for special triangles. We already encountered the right triangle—whose area is simply one-half the product of its legs. For an equilateral triangle, we have two convenient formulas. When we are given the length, s, of a side of an equilateral triangle, we have the formula

However, when we are given only the length, h, of the altitude of the equilateral triangle, then we can use the formula

PARTITIONING A TRIANGLE

Now that we have developed ways of finding the area of a triangle, given the measures of its various parts, we can begin to determine how to find the areas of portions of a triangle. For example, when we draw the median of a triangle, we will have divided the triangle into two triangles of equal area. In figure 7-11, where AD is a median of triangle ABC, we notice that triangles ABD and ACD have equal bases, BD, and DC, and share the same altitude AE. This clearly implies that they have the same area.

If in figure 7-12 we draw a cevian from point A to meet BC at a point D one-third the distance from point B to point C, then, using the same argument as above, we will have triangle ABD having one-third the area of triangle ABC.

We are now ready to determine how the three medians of a triangle will partition the triangle's area. Obviously, there will be six triangles formed. But how will the areas of these six triangles compare? Using the case just described above, we can show that the three medians of triangle ABC shown in figure 7-13 separate the triangle into six triangles of equal area. To see how this is true, we begin by noting that the area of triangle ADC has half the area of triangle ABC.

However, since point G is the trisection point of each of the three medians, we also have

We could repeat this for each of the six triangles shown in the figure. Thus, we can conclude that the medians of a triangle partition the area of the triangle into six triangles of equal area, even though they may have different shapes.

A true surprise now lies before us. If we draw the circumscribed circle for each of the six triangles of equal area we noted in figure 7-13, we will find much to our amazement that their centers all lie on the same circle, as shown in figure 7-14.1

We now can put these triangle-area findings to use. Suppose we are told the lengths of the three medians of a triangle are 39, 45, and 42 units long. How might we be able to find the area of this triangle?

In figure 7-15, we shall let AD = 39, BE = 45, and CF = 42. Then, because of the trisection property of the centroid, AG = 26, GD = 13, BG = 30, GE = 15, CG = 28, and GF = 14.

We will extend GD its own length to point K (as shown in figure 7-15), so that GD = DK. Then quadrilateral CGBK is a parallelogram (since the diagonals bisect each other). We have the side lengths of triangle CGK as 26, 28, and 30 with the semiperimeter 42. Using Heron's formula we get the area of triangle CGK as

= 336.

= 336.

Yet half the area of this triangle CGK (triangle GDC) is 168, which we showed above is one-sixth of the area of the entire triangle. Therefore, the area of triangle ABC is 6 · 168 = 1,008.

Now that we have a method for partitioning a triangle into six equal-area triangles, we will show how we can partition a triangle into four equal-area triangles. To do that, we simply draw line segments joining the midpoints of the sides of the triangle, as shown in figure 7-16. These four triangles are all congruent to each other (by SSS), since the lines FE, DF, and DE are parallel to the sides of the original triangle; and thus, each is one quarter of the original triangle. The triangle DEF is the so-called medial triangle.

Using the property that a cevian divides a triangle's area proportional to the segments along the side it partitions, we can now entertain ourselves with lots of geometric configurations that use this property. Take, for example, triangle ABC (shown in figure 7-17a), where D is the midpoint of BC, E is the midpoint of AD, F is the midpoint of BE, and G is the midpoint of FC. We can show that the area of triangle EFG is one-eighth of the area of triangle ABC. To do this we simply apply our previously established relationship with the median cutting a triangle into two equal areas.

We begin with the altitude of triangle ABC drawn to side BC and realize that it is twice as long as the altitude of triangle BEC drawn to side BC. Therefore, since the two triangles share the same base, Area ΔBEC = ½ Area ΔABC. With CF as the median of triangle BEC, Area ΔEFC =  Area ΔBEC. Similarly, with EG the median of triangle EFC, Area ΔEFG =

Area ΔBEC. Similarly, with EG the median of triangle EFC, Area ΔEFG =  Area ΔEFC. Putting this all together, we find that Area ΔEFG =

Area ΔEFC. Putting this all together, we find that Area ΔEFG =  Area ΔABC.

Area ΔABC.

You might want to try other such configurations, such as if BD =  BC, AE =

BC, AE =  AD, BF =

AD, BF =  BE, and CG =

BE, and CG =  CF (shown in figure 7-17b), what part of the area of triangle ABC would be the area of triangle EFG?2 Try some other variations and see if a pattern emerges.

CF (shown in figure 7-17b), what part of the area of triangle ABC would be the area of triangle EFG?2 Try some other variations and see if a pattern emerges.

We partitioned a triangle into two equal areas by drawing a median (CS). However, suppose we wish to partition a triangle into two equal areas by drawing a line from a given point (P) on a side to a point (R, or R′) on another side. Using triangle ABC in figures 7-18a and figures 7-18b, we select at random the point P on side AB, and through that point we would like to draw a line that will cut the triangle into two equal areas (figure 7-18a: for all points P between A and S; figure 7-18b: for all points P between B and S).

Our goal, now, is to show that we can, in fact, draw a line through this randomly selected point P that will separate the triangle ABC into two equal-area regions. First, we will draw the median CS. Through point S we draw a line parallel to CP, intersecting BC at point R (or intersecting AC at point R′ as shown in figure 7-18b). Our claim is that the line PR (or PR′ in figure 7-18b) is the line we seek.

Begin with the notion that the median of a triangle separates it into two equal-area triangles. Therefore, we begin our construction (figure 7-18a) by drawing median CS, giving us that Area ΔACS –  Area ΔABC. Since triangles PSC and CRP have equal altitudes and share the same base (PC), they have equal areas. If we subtract the area of triangle PQC from each of these two triangles, we have AreaΔPQS = AreaΔRQC. Now,

Area ΔABC. Since triangles PSC and CRP have equal altitudes and share the same base (PC), they have equal areas. If we subtract the area of triangle PQC from each of these two triangles, we have AreaΔPQS = AreaΔRQC. Now,  Area ΔABC = Area ΔACS = AreaΔPQS + Area PQCA = Area ΔRQC + Area PQCAS = Area APRC. Therefore,

Area ΔABC = Area ΔACS = AreaΔPQS + Area PQCA = Area ΔRQC + Area PQCAS = Area APRC. Therefore,  Area ΔABC = Area APRC = Area ΔBPR. Thus, PR divides the triangle ABC into two equal areas, which was our original goal. Analogously, for figure 7-18b, we have the same conclusion.

Area ΔABC = Area APRC = Area ΔBPR. Thus, PR divides the triangle ABC into two equal areas, which was our original goal. Analogously, for figure 7-18b, we have the same conclusion.

We can also use this technique to trisect the area of a triangle by drawing lines through a randomly selected point, P, on one of the triangle's sides (see figures 7-19a, 7-19b, and 7-19c). In figure 7-19b, the lines (through point P) that trisect the area of triangle ABC are PR and PS. To accomplish this, we begin by trisecting BC, with points T and U. By drawing lines TR and US parallel to AP, we will have determined points R and S on AB and AC, respectively. Using a procedure similar to that above, we can show that PR and PS are the two lines that trisect the area of triangle ABC.

This technique actually enables us to partition a triangle into any number of equal-area regions by drawing lines through one point on the side of the triangle.

Furthermore, we could also use this technique to create a triangle equal in area to a given triangle and sharing a common baseline. More specifically, we would want to construct a triangle equal in area to triangle ABC, and having BD as its base, where D is on BC, as shown in figure 7-20.

By drawing a line (CE) parallel to AD and to intersect BA (extended) at point E, we can form triangle BDE, which is equal in area to triangle ABC. This is so because Area ΔAED = Area ΔACD (same altitude for base AD), and we can add triangle ABD to each of these two equal-area triangles to get the desired result.

NAPOLEONO'S THEOREM REVISITED

Our earlier study of Napoleon's theorem (see p. 69 and those following) has an extra feature; it has a lovely application to triangle areas. Although it may be a bit complicated by overlapping triangles, the end result is quite astonishing. We consider Napoleon's theorem configuration (with the Fermat point F) as shown in figures 7-21a and figures 7-21b, where the three equilateral triangles are drawn on the sides of the original triangle ABC. We will add to this figure parallelogram AC′CD. This is done by drawing AD parallel, and equal to, CC′, which then creates parallelogram AC′CD. We then draw A′D.

We know that triangle AA′D is equilateral, since AD = AA′, and ∠AA′D = 60°. (See figure 3-9, p. 74.) Unexpectedly, a rather unusual relationship emerges, namely, that twice the area of triangle AA′D equals the sum of the areas of the three equilateral triangles on the sides of triangle ABC, plus three times the area of triangle ABC. Symbolically that reads:

2 ⋅ AreaΔAA′D = AreaΔABC′ + AreaΔBCA′ + AreaΔACB′ + 3 ⋅ AreaΔABC.

Follow along as we justify this rather counterintuitive claim.

AreaΔAA′D = AreaΔAA′C + AreaΔACD + AreaΔA′CD

= AreaΔAA′C + AreaΔACC′ + AreaΔAA′B,

since AreaΔACD = AreaΔACC′ (parallelogram AC′CD), and AreaΔA′CD = AreaΔAA′B

(ΔA′CD ≅ ΔAA′B; because AB = AC′ = CD, A′B = A′C, AA′ = BB′ = A′D).

We also have several triangle congruences in this diagram (figures 7-21a and 7-21b), which, of course, implies equal areas as follows:

ΔBB′C ≅ ΔAA′C ⇒ AreaΔBB′C = AreaΔACC′

ΔBCC′ ≅ ΔAA′B ⇒ AreaΔBCC′ = AreaΔAA′B

ΔABB′ ≅ ΔACC′ ⇒ AreaΔABB′ = AreaΔACC′

This enables us to state the following, which leads to the justification of our rather unexpected original claim.

2 ⋅ AreaΔAA′D = AreaΔAA′C + AreaΔAA′B + AreaΔACC′ +

AreaΔBB′C + AreaΔBCC′ + AreaΔABB′

= AreaΔABC′ + AreaΔBCA′ + AreaΔACB′ +

3 ⋅ AreaΔABC.

There are even further area relationships in this configuration to cherish. Consider, once again, Napoleon's theorem. Now we will focus on the equilateral triangle formed by the centers of the three equilateral triangles that were drawn on the sides of the original triangle, which is shown in figure 7-22 (see also figure 3-5, p. 70). This time we have 2 ⋅ AreaΔPQR = AreaΔABC +  (Area ΔABC′ + AreaΔA′BC + AreaΔAB′C).

(Area ΔABC′ + AreaΔA′BC + AreaΔAB′C).

We leave this justification to the reader.

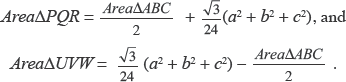

As we indicated earlier (see figure 3-8, p. 73), there is also an internal equilateral triangle—called the internal Napoleon triangle—created when the three side-equilateral triangles are placed internally on the three sides of the given triangle, that is, overlapping the original triangle ABC, as shown in figure 7-23, where triangle UVW is the internal equilateral triangle, and triangle PQR is the external equilateral triangle—called the external Napoleon triangle. Now here is a true secret of triangles: Who would imagine that the relationship of these two Napoleon triangles is that the difference between the areas of the external and the internal equilateral (Napoleon) triangles is the area of the original triangle? Symbolically we have

AreaΔABC = AreaΔPQR – AreaΔUVW.

To get a clearer picture of this amazing relationship we provide an “unencumbered” picture of this situation in figure 7-24 and some of the related lengths. First, we have in this diagram that the two Napoleon triangles, the external, ΔPQR, and the internal, ΔUVW, have their areas in the relationship

AreaΔABC = AreaΔPQR – AreaΔUVW.

These areas are

As a bonus, we offer the length p of each of the sides of equilateral triangle PQR as

where a, b, and c are the lengths of the sides of the original triangle ABC.3

INSCRIBED TRIANGLES

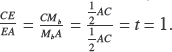

We say one triangle is inscribed in another triangle when the vertices of the first triangle are each on the sides of the second triangle. This can be seen in figure 7-25, where we say that triangle PQR is inscribed in triangle ABC. This leads us to a rather unexpected property: When two triangles are inscribed in a given triangle and are placed so that their vertices are equidistant from the midpoints of the sides of the given triangle, then they have equal areas. This is shown in figure 7-25, where triangles PQR and UVW are placed with vertices on each of the three sides of triangle ABC, with side midpoints so that

PMa = UMa = x, QMb = VMb = y, and RMc = WMc = z.

It then follows that AreaΔPQR = AreaΔUVW.

In figure 7-16, we showed an inscribed triangle situated with vertices on the midpoints of the sides of the original triangle. There the inscribed triangle was earlier shown to be  of the area of the original triangle. We can also consider an inscribed triangle that is placed in such a way that the vertices are on the trisection points of the sides of the original triangle as shown in figure 7-26. Here we can show that the area of the inscribed triangle is

of the area of the original triangle. We can also consider an inscribed triangle that is placed in such a way that the vertices are on the trisection points of the sides of the original triangle as shown in figure 7-26. Here we can show that the area of the inscribed triangle is  of the area of the original triangle.

of the area of the original triangle.

We can justify this claim in a rather simple way. Recall that a cevian divides the area of a triangle proportional to the segments it determines along the triangle side to which it is drawn. Therefore, the area of triangle ABD is one-third the area of triangle ABC. However, using similar reasoning, AreaΔBDF =  AreaΔABD.

AreaΔABD.

Consequently, AreaΔBDF =  ⋅

⋅  AreaΔABC =

AreaΔABC =  AreaΔABC.

AreaΔABC.

A similar argument can be made to show that AreaΔCDE =  AreaΔABC.

AreaΔABC.

Again, we can show that AreaΔAEF =  AreaΔABC.

AreaΔABC.

Thus,

AreaΔDEF = AreaΔABC – (AreaΔBDF + AreaΔCDE + AreaΔAEF),

which, with appropriate substitutions, can be restated as AreaΔDEF = AreaΔABC – ( AreaΔABC +

AreaΔABC +  AreaΔABC +

AreaΔABC +  AreaΔABC) = AreaΔABC ⋅

AreaΔABC) = AreaΔABC ⋅  =

=  AreaΔABC.

AreaΔABC.

Another way to establish that the area of triangle DEF is one-third the area of triangle ABC is to do the following (use cevian BE):

AreaΔDEF = AreaΔADF + AreaΔADE – AreaΔAEF = AreaΔABC ⋅ =

=  AreaΔABC.

AreaΔABC.

The reader might try to show how the area of an inscribed triangle relates to the original triangle, if the vertices of the inscribed triangle are each one-fourth of the distance from each of the original triangle's vertices (consecutively).

AREAS DETERMINED BY INTERSECTING CEVIANS

We can find some surprising triangle area relationships from the trisection points on the sides of a triangle. In figure 7-27a, we have triangle ABC with trisection points marked along each of its sides. The three cevians AD, BE, and CF drawn to the trisection points on the sides of triangle ABC, determine triangle PQR. It turns out that4 AreaΔPQR =  AreaΔABC.

AreaΔABC.

If we now look to figure 7-27b, we can get another triangle (UVW) using the cevians AG, BH, and CJ that generates the same result. Namely, AreaΔUVW =  AreaΔABC. In other words, surprisingly, the triangles PQR and UVW have the same area. Moreover, we should note that these two general triangles typically are not congruent, are not similar, and do not have the same perimeter. This adds to the curious relationship of their equal areas.

AreaΔABC. In other words, surprisingly, the triangles PQR and UVW have the same area. Moreover, we should note that these two general triangles typically are not congruent, are not similar, and do not have the same perimeter. This adds to the curious relationship of their equal areas.

We can even take this configuration a bit further. Using the trisection points shown in figure 7-28a, it can be shown5 that the

AreaΔPQR =  AreaΔABC.

AreaΔABC.

Joining the other intersection points of the intersecting cevians as shown in figure 7-28b produces triangle UVW, which is one-sixteenth of the area of triangle ABC, which is stated symbolically as

AreaΔUVW =  AreaΔABC.

AreaΔABC.

Now, unlike the earlier situation where we had two triangles of equal area and their shapes were not at all related, her we have—surprisingly—two triangles PQR and UVW (shown in figures 7-28a and figures 7-28b) that are each similar to the original triangle ABC, and then, of course, similar to each other—as opposed to the two triangles PQR and UVW in figures 7-27a and 7-28b, where this was not the case. This can be seen by noticing that the corresponding sides are parallel (e.g. AB||QR||UW). We also note that AB = 5 ⋅ QR, and AB = 4 ⋅ UW. With this information, we can conclude that AreaΔUVW =  AreaΔPQR.

AreaΔPQR.

When we consider the hexagon formed by this side-trisecting cevians (figure 7-29a) we find that the AreaPUQVRW =  AreaΔABC. We should note that there is no constant relationship between the perimeters of these two figures.

AreaΔABC. We should note that there is no constant relationship between the perimeters of these two figures.

As if this isn't enough of a surprise, a further relationship exists if we consider other points of intersection of the cevians as shown in figure 7-29b. In this case, AreaKXLYMZ =  AreaΔABC. Yet, now we do have a relationship between perimeters. That is, PerimeterKXLYMZ =

AreaΔABC. Yet, now we do have a relationship between perimeters. That is, PerimeterKXLYMZ =  PerimeterΔABC. It is curious that for the hexagon PUQVRW we had no relationship of the perimeter to the original triangle, whereas for the hexagon KXLYMZ we do have a perimeter relationship.

PerimeterΔABC. It is curious that for the hexagon PUQVRW we had no relationship of the perimeter to the original triangle, whereas for the hexagon KXLYMZ we do have a perimeter relationship.

Now by taking the combination of these two areas, we get a shape shown in figures 7-30a and figures 7-30b, which are hexagrams—two six-corner stars P-U-Q-V-R-W and K-X-L-Y-M-Z. (We use the dashes between points to denote hexagrams—as opposed to hexagons.)

It turns out that the Area P-U-Q-V-R-W =  AreaΔABC (figure 7-30a), and

AreaΔABC (figure 7-30a), and

Area K-X-L-Y-M-Z =  AreaΔABC (figure 7-30b).

AreaΔABC (figure 7-30b).

Once again satisfying our curiosity about the relationship between perimeters—if one exists—we can conclude that Perimeter P-U-Q-V-R-W =  PerimeterΔABC. We cannot make any such claim for the hexagram K-X-L-Y-M-Z.

PerimeterΔABC. We cannot make any such claim for the hexagram K-X-L-Y-M-Z.

So you can see that the side-trisecting cevians provide some rich triangle-area applications, the justifications for these we leave to the ambitious reader. One might also consider how the above relationships manifest themselves when the original triangle is equilateral. Another tack to take in pursuing further investigations is to consider cevians drawn to points that partition each side into four or more equal parts. There are many pursuits one can take for further explorations here.

Suppose you have drawn two medians and a side trisector from the third vertex—as shown in figure 7-31. Here we have, interestingly enough, the triangle formed in the original triangle having  of the area of the original triangle.

of the area of the original triangle.

We show this in figure 7-31, where points Ma and Mb are midpoints of their respective sides of triangle ABC, and point F is a trisection point of side AB. Because AMa and BMb are two medians, their intersection point Y is the centroid G of the triangle ABC. It can be shown that

AreaΔXYZ =  AreaΔABC.

AreaΔABC.

The proof of this unexpected relationship is based on Routh's theorem6 (1896). This states that for triangle XYZ (figure 7-32), formed by the intersecting cevians in triangle ABC,

we have  and

and  It follows that

It follows that

Applying this to the figure 7-31, we get

and

and

We can also see Ceva's theorem (see chapter 2, p. 43) as a special case of the Routh's theorem. If the cevians AD, BE, and CF meet at a common point (i.e., X = Y = Z), then the area of triangle XYZ is zero, then we can conclude by Routh's theorem that  = 1, which is Ceva's theorem.

= 1, which is Ceva's theorem.

It is always nice to see these consistencies throughout mathematics!

Many more such interior triangles can be formed with the various cevian partitions of a triangle.7 Finding the area relationships, and establishing their truth, can be challenging, but surely worth the effort! We encourage the reader to embark on this rewarding path.

We can conclude this chapter by showing how we can find a triangle equal in area to a given polygon. We will apply this unusual procedure to a pentagon, but surely it can be used with other polygons as well.

To construct a triangle equal in area to pentagon ABCDE (shown in figure 7-33), we begin by drawing GE||AD, and FB||AC. Since triangles AED and AGD share the same base (AD), and have equal altitudes to that base, they are equal in area. Similarly, triangles ABC and AFC are also equal in area. Thus, with appropriate replacements, we find that triangle AFG is equal in area to pentagon ABCDE.

We have now covered the area of a triangle from its definition and the basic formula through many other formulas that are not too well known. Yet with the above technique that enables us to construct a triangle equal to the area of a given polygon, we can then find the area of an irregular polygon quite easily. This is a fine way to expose a well-kept secret of the triangle's power.