4

4

The Miracle of Middle Voice

NOW THAT you’ve laid a solid foundation of easy, relaxed breathing, we can move into the heart and soul of our work together. I’m very excited about introducing you to the technique that sets my work apart from that of every other teacher. It’s allowed me to create the miracles that have made my brand famous all over the world, and by the end of this chapter, you’ll be on the path to mastering it.

As people sing from low to high, most of them concentrate on the extremes. How low can you go? How high can you fly? They work hard—sometimes for years—to expand their range, looking for ways to push the envelope. But very few of them have come to terms with the fact that a huge part of their voice is missing.

The exercises in this chapter, and the discoveries you’ll make as you do them, will change your voice forever, and I guarantee that if you stay with me as we cover the material here and on the audio tracks on the website, you will feel and hear profound shifts in your voice that take you into undreamed-of territory. Where are we headed? Into the shrouded-in-mystery, overlooked, and unacknowledged key to vocal freedom: the middle voice.

The middle voice is the bridge between the familiar low voice most of us speak with (called chest voice) and the voice nestled way above our speaking voice (called head voice). This incredible, little-recognized part of the voice, which I specialize in helping people strengthen, is responsible for bringing a new kind of power and ease to both speaking and singing. Once you find it, you can sing without tiring your voice, relieve the pressure that builds in your throat and jaw, and, as you’ll see, almost miraculously gain smooth access to the entire range of your voice.

For speakers, developing middle voice will give access to a new palette of resonances. What does that mean to you? Think about the range of colors you hear in the voice of a great actor, or a memorable speaker like Martin Luther King. That’s the everything-but-monotonous world of possibilities middle voice opens up for you. And it’s fabulous training for another reason: to find it, you must let go of pressure and strain in your voice. Using the middle-voice exercises is a litmus test for speakers. When you are able to find middle and play with it, you can be assured that you are breathing in a way that will keep your voice strong and powerful, and that you have learned to release the gripping muscles that keep your voice trapped, earthbound, or unreliable.

Middle voice will add gorgeous overtones to the way you speak. It will add a crisp, bright, and pretty sound to the lower register you’ve spent most of your speaking life in—and it will add high-end flair and color to a voice that’s been low, husky, and dull.

Let me show you how the discovery of middle voice worked for two of my students, one a number of years ago and one more recently, because I’d like you to understand what’s possible, and what you can expect, as you work with the exercises I’ll teach you in this chapter. Yes, it will take effort. But the results will amaze you.

A Short Push to Freedom

A well-known manager in the music industry called me at the end of 1997 to ask me to work with a new group that was already on tour and starting to get significant airplay with its first single, called “Push.” At that time I’d never heard the song, and I wasn’t familiar with the group, Matchbox Twenty. The manager explained that the lead singer, Rob Thomas, was wonderfully talented but was becoming terribly hoarse from performing night after night.

Rob came in for his first meeting with me carrying a CD of his music as a gift and a guide to the kind of music he was making. He opened the cover, pulled out the photo, and signed it with the words, “Please make me sound as good as I do on this record.” He explained that he was totally comfortable singing in the studio because when his voice got tired, he could say, “Later,” and come back another day. But when he was onstage in front of a cheering audience, he didn’t have that option. He wanted and needed help.

Rob has a bluesy, gravelly voice that’s brimming with emotion and style. But because he was trapped in his speaking voice—chest voice—as the notes got higher in the range, he was straining terribly to reach them. I showed him the series of exercises you’re about to learn, and as middle voice opened up for him, he realized that he no longer had to force the top notes. That revelation, he said, was like a gift from God. He and the band used practice tapes much like the warm-ups I’m about to walk you through, and with a program of fifteen minutes of practice a day, the whole band was able to perform, sometimes five shows a week, with no strain, no hoarseness, and no lost voices. In the months that followed, they went on to sell more than ten million copies of the CD.

Gwen Stefani had a similar middle voice revelation when I started working with her. I had been teaching her then-husband Gavin Rossdale, the front man for the group Bush, and Gavin bragged to her about the progress we had made with his voice. So as she was getting ready to head out on a yearlong tour, Gwen decided to come in for a lesson. When I vocalized her through some exercises to see what was going on, I realized that she had a powerful chest voice and head voice, but that she was still straining at the top of chest voice and not moving into middle. When I showed her how to do that, and she realized there was another voice she’d never heard about, she was shocked and excited. I gave her the exercises to make her middle voice grow, and sent her off on tour.

A year later, I saw her at a party and she came up to me saying, “Roger, you changed my life.” I started smiling uncontrollably. “I practiced your warm-up exercises every night before I went onstage, I used the middle voice, and I have never had greater performances,” she told me. “My voice held up every night and sounded amazing.”

That’s what middle voice can do.

Meet the Zipper

To understand where the ease comes from when you find middle, you need to know a little about how your voice works. Remember, there are three different parts of the voice—chest, middle, and head—and each works in a slightly different way, as illustrated in the diagram below. When you’re in chest voice, the vocal cords are supposed to be vibrating along their full length, like the long, thick strings of a piano. Chest voice—as you would guess—feels like it resonates in the top part of your chest. If you put your hand just below the seam where your neck meets the top of your chest and say, “I can speak in chest,” you should feel a slight vibration in your hand.

As you move higher in the range, a kind of zipper effect begins to close off one end of the cords (this is called dampening). When this “zipper” moves up to the point where only 50 percent of the length of the cords is vibrating, you are in middle voice.

In middle voice, you should feel the vibration partially leave the chest area and move closer to the area just behind your nose and eyes. This area has been given many names over the years, but it’s most commonly called the mask. The air and tone bouncing around the sinus area can feel as gentle as a minor flutter or buzz. Close your lips and say mmmmmmmm. You should feel your lips vibrating as sound hits them from the inside of your mouth. This is very similar to the vibration you’ll feel in middle, though in middle it’s a bit closer to the nose.

CHEST, MIDDLE, AND HEAD

As the zipper continues to close and only one-third of the vocal cords vibrates, you reach head voice. In head voice, you’ll feel none of the resonance of chest voice, and you’re far from the voice you use when you speak. Now you’ll feel air and sound vibrating primarily behind your eyes and nose, in the highest reaches of your sinuses.

To achieve fluidity in your voice, the object is to allow the vocal cords to open and close smoothly through their whole range of motion without creating any strain or pressure. (What I’ve called the zipper is actually the result of phlegm building up at the end of the cords and creating the zippering effect.)

The main job of the vocal cords is to be a filter for the air. They simply decide how much air gets through. And to allow them to open and close smoothly in the filtering process, you need to send enough air to the cords to make them vibrate as rapidly as they need to, but not so much that it forces the zipper wide open with insufficient cord vibration.

In chest voice, the vocal cords are at their longest and thickest, so they can handle a tremendous amount of air. As the vocal cords zip together and get shorter in middle voice, they can’t withstand the same volume of airflow, and in head voice, with the smallest area of cord vibration, they can handle even less. To make sounds through the entire range, I repeat: It’s vital to send just the right amount of air to the cords as they change length.

There’s an interesting irony here that emphasizes the same point I made about breathing: pushing hard, straining, and tightening up your body in an effort to make the zipper work is like using a jack-hammer when a gentle tug will do. All the straining we so commonly put into reaching for the heights, both musically and as we work to make points persuasively in speech, is completely counterproductive. The incredible stress that Rob Thomas was using to get to the high notes in his band’s music kept the zipper from closing. The harder he pushed, the more the cords locked up and tried hopelessly to hold the air back. That made him more likely to get hoarse, not higher or stronger. The ease that freed him came from allowing his voice to slide into middle. The same thing happened for Gwen. Going into middle took all the pressure off the cords and kept her voice healthy for those long months of touring.

Where’s Middle?

I teach middle to everyone because I consider myself to be the equivalent of a piano builder. My job is to ensure that the complete instrument—that is, your entire voice, top to bottom—is usable. In case you don’t know how much ground your voice should be able to cover, let me get specific for a minute.

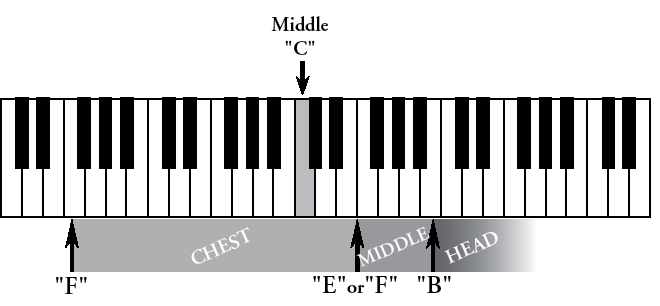

For the average man: Chest voice starts at low E or F, which is twelve or thirteen white keys below middle C on the piano (see diagram). It goes up for about two octaves (twenty-three or twenty-four notes), reaching middle voice at around the E or F above middle C. Middle voice runs from that E or F to about B-flat or B-natural. Above that, from C and beyond, you’re in head voice.

The practical meaning of all this is that men can do almost all the singing and speaking they want to in chest and middle voice (Pavarotti sang opera in the range covered by chest and middle). For you, head voice is probably going to be an interesting sidelight, but not much more. Mastering middle is essential.

MALE RANGE

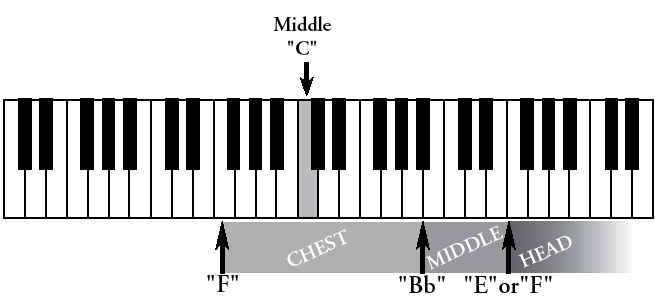

For women: Chest voice starts at the F below middle C and continues up for just seventeen notes to the B-flat above middle C (see diagram). Middle voice covers the next six notes or so, and ends around E or F. And the rest is head voice. You’ll hit middle sooner in the exercises than men will because physically you have less chest range—your vocal cords are thinner and shorter. (You do, of course, make up for it by having more head voice than a man.) If you’re a singer, you’ll want to practice moving smoothly from middle to head also.

Many people are shocked, after hearing me emphasize middle voice so heavily, that middle covers such a small span of notes. As we’ve seen, it’s a total of about six half steps altogether. But middle is a pressure valve, a bridge and a proven pathway to strengthening the entire voice. Most people feel as though they’re six feet tall in a room with a six-foot ceiling when they sing or speak higher in the range. At the top of chest, it feels as though there’s nowhere to go but down. Middle raises the ceiling to ten feet, so you can jump up and down whenever you feel like it without crashing into a barrier.

You need every part of your voice. Together we’ll shine, polish, repair, and replace any sections of the voice that don’t serve you well. I never expect that every single note will be used every day, but I want to give you the confidence to reach for any one you want and know it’s there for any purpose.

FEMALE RANGE

Let’s Go for the Middle

Ready? First I’d like to be sure you understand what middle voice sounds like. Listen to audio 14 on the website and you’ll hear a demonstration that begins with chest voice, then moves into the short passageway that is middle voice, and winds up in head. You’ll notice that I point out just where middle begins and ends so there’s no guesswork about it. Listen until you really hear it.

You’ll notice that chest voice has a thick, open quality, while head voice is flutelike, with sweet, subtle high overtones. Middle combines the best elements of the two. The lower portion of middle is supposed to sound almost exactly like chest voice, and as we inch higher, it gradually picks up the sound colors of head voice. It’s a lot like mixing paint. If you think of chest voice as being black and head voice being white, what we’re doing with middle is blending the whole spectrum of grays that fall between the two. Skillful combining will create a seamless movement from low to high.

The One-Octave Exercise

Want to try it? To begin, I’d like you to spend a few minutes reconnecting with what you now know about breathing. Consciously practice letting smooth, deep breaths flow in and out. Then listen to audio 15 (male) or audio 16 (female) and follow along, maintaining your smooth breathing. What you’ll hear—and then copy yourself—is your first vocal exercise, a series of sounds in a rhythmic pattern that begins a half step higher each time you do it. This exercise is called the one-octave series because—you guessed it—each exercise covers one octave of range. The specific syllables we’ll use—goog, gug, moom, mum, no, nay, nah (which we’ll repeat in many of the exercises)—are designed to direct progressively greater amounts of air toward the vocal cords. That means you’ll start with small, easier-to-control amounts of air and move toward being able to shape larger amounts.

Basically, the syllables themselves, because they position your throat and tongue and help regulate the flow of air, set you up physically to find middle voice. What you need to do is keep going as the exercise gets higher—at the same volume from beginning to end. This is important: Getting louder will not help you find middle. It’s almost sure to prevent it because it sends more air to the vocal cords than they can handle as they try to find the middle position.

If you feel a large buildup of tension and pressure when I say go to middle, stop and try it again, keeping your breathing even and your volume constant. Try this a few times. You’re exploring—feeling your way toward middle.

What happened when you got to the top of chest and took your next steps up the scale? How smooth was the transition? Was there a big yodel-like break? At the top of chest, the voice may go into a very different place, which is thin and high. In fact, the low voice and the high one might sound as though they belong to two entirely different people. That’s not the blending you want. It means you’ve skipped middle and rocketed into head voice.

Do the exercise again, this time trying to make the high sounds more like the lower ones. Don’t expect the shift from low to high to be perfectly smooth in the first few attempts. This is a learning process. You may notice that there’s a small break in your voice as you make the transition to middle, then a weak middle, produced without strain, that carries some of the resonance of the chest voice. What you’re looking for is a voice that sounds almost as thick as chest voice but feels like it is vibrating both behind your nose and at the top of your chest.

I know this sounds complicated, but I want to remind you that the voice wants to find middle. It wants to shift gears easily, without grinding, stopping, or feeling that the body is squeezing so hard that only a squeak comes out. Play with this!

First Helper: The Cry

Sometimes you’re just a step away from middle and one little push will get you there. So I’d like you to try the one-octave exercise again, singing only googs and gugs, this time using a special sound that I call the cry. You’ll hear it on audio 17 (male) or audio 18 (female) on the website. The cry is an amusing sound that might make you feel like a cartoon character pretending to be sad. Imitate the sound as closely as you can, and enjoy yourself. This is supposed to be fun.

The cry works by concentrating the flow of air at the back of the throat and helps the air navigate successfully both below the soft palate and above it, into the nasal area. It works to give the breath a boost into the right position so you can feel and hear it.

If you’re like many, many students, the cry may take you straight into middle.

But for those who get stuck, have questions, or want more illumination, let me show you how other students have dealt with the most common problems and concerns.

Slipping into Middle

Ryan is the choir director and head of the vocal department of a private school in Los Angeles. He has a substantial knowledge of music, but he had never fully grasped the concept of middle, and he was intrigued when we began to work together. Ryan’s first attempts to find middle had him pushing and straining when he got to the top of chest voice. He was trying to muscle those rich sounds higher in the range while keeping them vibrating only in his chest. I made him aware of the straining, and as he allowed himself to relax, we tiptoed into a very thin, hard-to-hold-on-to middle voice that was light and airy. It was so fragile that only some sounds allowed him to cross into middle. He especially liked mum and had trouble with many of the other syllables.

You may notice this yourself. You may do well with one sound and not another—and at the beginning, this is fine. Our first goal is for you to have the sensation of getting into middle. Let me tell you a little about how each of the sounds works and what a preference for one sound or another might say about you.

Goog and gug. The g sound on both sides of the vowel momentarily stops the air from going through the cords (this is known as a glottal stop). At that moment, the cords have an extra split second to move to the right position before the air hits them. The vowels themselves allow slightly different amounts of air through: the oo is fairly closed, while the uh opens the throat up a bit more.

Moom and mum. These two syllables allow you to play with a wee bit more air. The m sound allows a small stream of air to keep coming through the cords, even when the lips are closed. Remember how I mentioned that middle voice vibrates in the mask area? The m sound helps redirect the air into that area by sending some of it above the soft palate (the back of the roof of the mouth).

No, nay, nah. When you use these syllables, you’ll notice that the vowel sounds aren’t closed off at the end by a consonant, so the airflow is a little stronger and less interrupted. The nay and nah sounds are a bit harsh. They’re called pharyngeal (it means throaty), and they put the cords in a thicker, longer position for more volume and strength. When I give you a harsh sound to make, never worry that your voice will be trapped there. These are just tools to get you to the next place.

An important note about diction: Because these sounds are designed to place air in precise places, pronunciation counts. As you practice with them, be sure that your goog is a goog and not a good or a goo. It’s easy to get careless as you’re concentrating on where your voice is going and how it feels, so remind yourself to check in once in a while and go through an exercise focusing on quality control and keeping the syllables exact. It’ll make a big difference. As you go higher, the corners of your mouth may start to widen. You need to be very careful to maintain the same mouth and lip position whether you’re high or low. It’s possible to drop your jaw to get more space, openness, and resonance for the higher notes without going wide with the corners of your mouth and losing the pureness of the syllable.

Accept, as Ryan did, that certain sounds will fit more easily, at the beginning, into your mouth and the back of your throat. And the rest will come with practice.

Preparing the Throat

When middle is tentative and elusive, as it was for Ryan, we often need to help the throat physically prepare to enter middle. Ryan found the “cry” sound, which you learned earlier, to be very effective, and that removed one obstacle from his path. He also had another easy-to-solve problem: his larynx was too high in his throat and was constricting the flow of air.

Go back to the personal vocal inventory you did in chapter 2 and see if you diagnosed yourself with a high larynx. If so, listen to audio 19 and you’ll hear how it sounds to combine the low-larynx sound you learned earlier with any of the exercises. You can do this anytime you feel your larynx rising. A lot of you will have a high-larynx condition, and you’ll want to work often with this technique.

If you find you continue to be troubled by this extremely common condition, do two things: keep working on the middle exercises in this chapter, and add the series of low-larynx exercises you’ll find in chapter 7, which explains high-larynx problems and their solutions in detail. Like Ryan, I’m sure you’ll see remarkable results.

Visualization: Watching Middle Happen

I’m a strong believer in the idea that the more you understand about what’s happening in your body as you speak and sing, the better you’ll sound. So I often ask students to visualize what’s happening inside as a way of making a stronger connection to the changes that take place as they move from chest into middle. In chest voice, the back part of your throat should be very open. You should feel very strong and powerful as a large amount of air comes through the vocal cords and the cords easily handle that.

As you get to the top of chest, though, you need to allow some of the air to move into the sinus area, behind the nose. I asked Ryan to use the following visualization to help him make this transition more smoothly:

Close your eyes and do the one-octave exercise. As you make the sounds in chest voice, imagine the air filling up the throat, coming into the mouth, and leaving through your lips. Give the air a color. Imagine blue or purple air moving up along this chest-voice pathway. As I say go into middle, visualize the color moving higher at the back of your throat and entering the area behind your nose. Feel the color vibrating there.

This sensory cue helped Ryan perceive the shifts his body was making as he entered middle, and helped him connect with and strengthen his sound.

Back to Breathing: Is It Popping?

Because Ryan had a tendency to tense up as he did the exercises, we checked in frequently to be sure that his voice had a consistently solid base of breath to build on. As you go through the one-octave set, especially if you’re having trouble finding middle, be aware of what’s happening with your stomach. Are you doing “popcorn breathing,” pulling in your stomach with each goog or gug? If so, try the exercise again, this time consciously smoothing out the breath.

No matter what your throat and mouth are doing in an exercise that feels staccato, your breathing should remain constant: one inhale and one exhale instead of a series of rapid-fire puffs. The sounds themselves will break the airflow into manageable chunks—you can’t, and won’t, help by firing a series of short, percussive blasts at your vocal cords. As we’ve seen, that’s a recipe for trouble. Your stomach needs to come back in smoothly and evenly regardless of the sounds made.

Too Much of a Good Thing

Ryan had one final problem, also fairly typical, that stood between him and middle: too much phlegm. Phlegm is mucus of the throat, and it’s the substance that lubricates the vocal cords. Phlegm, as I tell all my students, is a good and a bad word. Without phlegm, even small amounts of talking or singing would irritate the cords. But too much poses an interesting problem: it keeps the cords from closing as they should.

You’ve seen how the cords need to zip closed to precise places to produce middle and head sounds. The edges of the cords need to meet exactly and close tightly. But when there’s an abundance of phlegm in the throat, the substance holds the cords apart instead of sealing them. It’s like trying to close a Ziploc bag around a pencil that’s sticking out of the top. You can close both sides, but there’s a gap at and around the pencil. This kind of separation in the vocal cords can create a slushy, airy, rumbly sound and makes it very difficult to hold the cords in the middle position.

Ryan learned how to control the amounts of phlegm his body was producing, using techniques I describe in detail in chapter 9, and he opened his voice to a realm of sound he’d never thought possible. If you find that you’re clearing your throat a lot and hearing hoarse or slushy tones as you do the exercises, don’t worry. Remember that we’ll deal with this problem later in the book.

Working the Obstacle Course

It took Ryan a while to feel fully comfortable in middle and strengthen it to its full richness. As you’ve seen, he ran into a host of obstacles—just as you may. But he kept moving through them, as we will, together. If you identify with a problem that Ryan, or the other students you’ll meet in this chapter, experienced, do what Ryan did: work on the targeted exercises to solve it. Then—and only then—move on to the next one. We’re not talking about years of work. We’re doing efficient, systematic problem solving. Your voice is likely to move through a lot of small interim improvements instead of presenting you with a five-minute miracle the first time you do the middle exercises. And that’s fine. I want you to own the technique, not just borrow or fake it. That means savoring the small changes and listening as they accumulate into something amazing.

Going Higher

Women doing the one-octave exercise might notice that it carries them into head voice. The seam joining the upper part of middle voice to the head voice is similar in feeling to the first seam, where chest meets middle. You’ll notice that, once more, pressure will begin to build; and once again, the way to make the smoothest transition is to relax, stop straining, maintain a constant volume, and allow your voice to go to a new place. This time it will feel as if air is concentrated high in your head, almost behind your eyebrows, and your voice will physically feel higher in your body.

A man needs head voice too, but by the time he gets to the top of middle voice, he’s already at high C, and that will get him through 99 percent of what he needs to do. It’s still important to me that both male and female singers reach vocal freedom by absolutely owning all three voices. I’ve given women more head voice in these exercises because they need it more. And at this stage of development, men won’t use it nearly as much. Please keep in mind, if you are a male singer, that once you’ve mastered chest and middle, you’ll want to go back and claim head voice as well.

Caution: No matter how much you’d love to hit the highest highs instantly, take your time. If you feel any strain at all, no matter where you are in the exercises, stop. If the voices on the audio track enter an area that’s beyond you today, stop and listen, then rejoin the exercise when it returns to the part of the range you own today. The notes you claim slowly, and without pressure or pain, are the ones that belong to you. There’s no rush.

A Note about Falsetto

Most people think that head voice and falsetto are the same thing, and the terms are used almost interchangeably. But these two places in the voice are entirely different. When you’re singing in head voice, you’re still allowing about a third of your vocal cords to vibrate. But falsetto is produced when so much air blows through the cords that they completely separate and only the outer periphery or edge of the vocal cords vibrates. Falsetto doesn’t use any of the normal inner-edge vibration at all.

Where head voice has a bit of the same buzz, edge, and vibration as chest and middle, falsetto is an island apart, and because of the way it’s produced, it will always have a detached sound. Many pop singers—think of the Bee Gees or Prince—have built their sound around falsetto, or used it to express a particular character in a song, but for our purposes, I’d prefer that you hold off using falsetto until you master the three genuine voices we’ve talked about. They’ll give you more control, and more power, and they’re much easier on the cords.

Expanding the Range

Now that the one-octave exercises have given you a handle on where chest, middle, and head voice go, how they sound and how they feel, I’d like to introduce you to the rest of the exercises in the basic vocal warm-up. The exercises we’re using to find and refine chest and middle voice are the same ones I prescribe to all the singers and speakers I work with to strengthen their voices every day. Each one is challenging in a different way, and each adds one more element that will allow you to control that magic ratio of air to vocal cord length that will give you the master key to your voice.

My Favorite, Most-Used Exercise: The Octave-and-a-Half Set

Listen to audio 20 (male) or audio 21 (female) on the website and do your best to follow along. You might have to listen a couple of times to hear the pattern.

This exercise will send you into middle fast, and it’s my hands-down favorite because it’s so efficient: it covers more range and gives you more opportunities to move through chest and middle than any other exercise I know. Because you’re covering more ground in this exercise, your voice learns more. And many people actually find it easier than the one-octave set because the top note is not repeated and it’s a little easier to control the airflow.

The same things you observed with the one-octave set will probably hold true here: the cry sound will help you anytime you use goog and gug. And you can add the low-larynx exercise anytime, if that’s been a concern.

You’ll get a great sense of where the holes are in your voice, and what blocks might be on your personal obstacle course, and I encourage you to keep playing with all the variables—from breathing to pronunciation and even phlegm—until your middle voice begins to shine.

The Octave Jump

When you feel comfortable with the octave-and-a-half set, or you just need a change, listen to audio 22 (male) or audio 23 (female) on the website for a demonstration of the octave jump. In this exercise you’ll hit a note, then hit the same note one octave above it (that might be a nice break after the rigors of the previous exercise). What makes this exercise interesting, and adds a new challenge, is that you’ll hold the high note before you descend. Until now we’ve been stepping fairly quickly up and down the scale, touching but not stopping on any of the notes. That quickstepping lets you zip the cords open and closed without any buildup of pressure. But sustaining a note requires you to hold the cords at one length for a moment or so, and in that time, air can build up behind the closed area of the cords.

You can visualize what’s happening if you wave your hand in front of your mouth as you’re blowing out a stream of air. Your breath only hits your fingers when your hand is right in front of your mouth, and no significant pressure develops. The second you hold your hand in the path of the stream, though, you’ll feel the air build behind the obstacle in its path. The effect, when this air buildup occurs as you’re holding a note, is that there’s a greater volume of air to control. It takes a bit more effort and strength—which you’ll gain with practice.

We’re using five syllables in this exercise, and two of them, goog and gug, are air-controlling sounds that make the sustaining easier. Experiment with these and see which one you like. Then work to build all of them into your repertoire.

Now That You’ve Got It, Use It

The series of exercises I’ve described will keep your voice going back and forth, up and down, until you start to feel and hear and get a sense of the real middle voice. At first it comes out of nowhere as a surprise. You’ll be doing the exercise and suddenly you’ll be singing very high, but still have the richness of your chest voice. The main difference, however, is that there is no pressure, no strain. You feel as comfortable as you do when you’re talking—but if you were to look at a keyboard, you’d realize that you are much higher than your chest voice ever went before. You’re creating a perfect blending of chest and head sounds that forms a unique sound all its own.

Whether you’re a singer or a speaker, middle voice is the key to sounding the way you were meant to. Middle voice gives you the room to navigate freely all the way through your voice, giving you low, bassy resonant tones mixed with midfrequency warmth and high-end sparkle.

With this series of exercises, you’ve got not only a wonderful learning tool but the basic warm-up that I give to all my students. You may want to add additional exercises to help you with a particular problem, but this is the core, and I’d like you to spend fifteen minutes a day, every day you can, working with them. That’s the best way I know to keep your voice, as an instrument, completely healthy. Vocal exercise is what the voice needs to maintain its freedom, and now that you’ve got the tools, you’re halfway there.

Please spend as much time as you need to with this material. You may find that you’re one of the many students who have an immediate epiphany the first time you do the exercises. Or you may fall into the group of students whose discoveries are earned by slow and careful experimentation. Your body, your habits, and your voice are unique—but the technique will lead you to a breakthrough.

I’d like you to practice what you’ve learned here for a week and see what you discover. In the next chapter you’ll find hints on how to practice to the greatest effect. Use what applies to you, and if you have questions about middle and whether you’re there, review the text and the exercises in this chapter. In chapter 6 you’ll find a deeper exploration of the process of finding and working with middle voice. We’re still on track and we have much to cover. Don’t think you have to be perfect yet—there’s more to learn. We’re still taking small steps. Stay with me. You’re doing great—and soon we will be running.