Spinach and Chard

Most box schemes grow more Swiss chard (white mid ribs, deep-green leaves), ruby chard (red mid ribs) and perpetual spinach (green mid ribs) than their customers know what to do with. The temptation of a simple and vigorous cut-and-come-again crop with few pests and diseases is more than most farmers can resist. After 20 years of chard abuse from customers (surpassed in volume only by cabbage abuse), I like to think youthful enthusiasm with the seed drill has been curbed by sensitivity to customer preferences.

Chards and their cousin, perpetual spinach, are actually more closely related to beetroot, sugar beet and mangolds (all Beta vulgaris) than to true spinach (Spinacea oleracea). True spinach is undoubtedly more succulent and, for most purposes, superior. Supermarkets normally sell only baby spinach with 5–8cm leaves but it is my experience that this has little culinary advantage over the larger-leaved types we grow. Unlike the more tolerant chards and perpetual spinach, true spinach is a highly strung sprinter, needing consistent and ideal growing conditions (irrigation, perfect soil, and, I hate to admit, fungicides). Since it is normally cut only once, a programme of frequent sowings is needed to provide true spinach throughout the season. It is difficult to grow organically (and consequently much more expensive), suffering from mildew and prone to bolt or go yellow in the presence of unrequited love, menstruating women, certain wind changes or just for the hell of it. We go on trying, but fail as often as we succeed.

In Devon we sow chard and spinach from April to August for harvest from June to November. Some growers seem to get away with sowing earlier, and you might be lucky in your garden, but without the advantage of fungicide-treated seed, the seed or seedlings too often rot in the ground. In a protected garden, chard and perpetual spinach will survive the winter and, with patient and selective picking, can provide a source of greens right through to the following May, when they will run to seed. We lack the patience, and our customers are fussier than some gardeners, so picking tends to stop with the first hard frost or big gale. Richard Rowan, one of our Cornish co-op growers, who has a protected farm on the banks of the River Tamar, runs some hungry sheep over his crop after picking in November. They graze the plants down to the ground and, in a good year, new, clean shoots appear after Christmas ready for a very welcome picking in April, when we are desperately short of home-grown produce.

Chard originated around the Mediterranean, possibly in Sicily, where it is prized more for the fleshy, white mid ribs than for the greens themselves. Perhaps not surprisingly, given its origins, it is more tolerant of heat and drought than the damp- and cool-loving spinach and has a better shelf life. There are various cultivars of Swiss chard, including the red-ribbed ruby, rainbow or rhubarb chard (probably three marketeers’ versions of the same thing). Though a pretty novelty, these variations tend to be bitter and tough when we have grown them and, like so many novelty vegetables, ultimately disappointing. Southern European cultivars are usually more compact in their growth, with thicker ribs reflecting their use in local cooking.

Storage and preparation

True spinach has a very short shelf life. Keep it in a plastic bag in the fridge and eat it within a couple of days. I would eat it stalks and all, unless they are very large, in which case it may be worth trimming them.

Perpetual spinach and chard will keep for longer. Don’t be put off by some wilting, which is not necessarily a sign of ageing and does not affect the flavour, provided it is not accompanied by yellowing. The stalks, or mid ribs, are best sliced or torn out and discarded, or, in the case of chard, cooked separately – put them on a few minutes before the leaf. Once cut, the stalks brown, so if you are not going to use them immediately, put them in water acidulated with lemon juice. In Mediterranean cooking, the stalks are used as a vehicle for various strong sauces. The green leaves of chard, cooked without their stalks, can be substituted for spinach in most recipes. They tend to be less bitter (lower in oxalic acid) and more succulent than perpetual spinach, but are never as succulent as true spinach.

Gnocchi Verde

These spinach and ricotta gnocchi make a delicious light alternative to the more usual potato or semolina ones. Use true spinach, if you can get it; it gives a better result than the perpetual variety (and is easier to prepare!).

Serves 4 as a starter

1 tablespoon butter

1 small onion, finely chopped

450g spinach, tough stalks removed

75g plain flour

150g ricotta cheese

2 egg yolks

100g Parmesan cheese, freshly grated, plus extra to serve

freshly grated nutmeg

sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

Sage Butter (see Rosemary Garlic Butter), to serve

Heat the butter in a small frying pan, add the onion and cook gently for 8–10 minutes, until soft but not coloured.

Blanch the spinach in a large pan of boiling salted water for 1 minute, then drain and refresh in cold water. Drain again, squeeze out the excess water and chop the spinach roughly. Add to the onion, seasoning well, and cook for about 8 minutes, making sure they are thoroughly combined. Tip the mixture into a large bowl and sift in the flour. Add the ricotta and mix well. Then stir in the egg yolks, Parmesan and some nutmeg and mix again. Season to taste.

Using 2 dessertspoons, shape the mixture into quenelles: take a spoonful of the mixture and then scoop it off with the second spoon, passing it from one spoon to the other until it is a neat oval shape. Place on a lightly floured tray and chill for 1 hour.

To cook the gnocchi, bring a large pan of salted water to the boil and add them in batches, being careful not to overcrowd the pan. When the gnocchi rise to the surface, give them about 3 minutes more, then scoop out with a slotted spoon and place in a warm serving dish. Serve sprinkled with Parmesan and drizzled with Sage Butter.

Spinach and Crab Frittata

Ideal for brunch or a light lunch. You could include diced roasted red peppers. For an Asian version, omit the Parmesan and nutmeg and add spring onions and chilli. Serve drizzled with oyster sauce.

Serves 4–6

400g spinach

3 tablespoons olive oil

1 onion, finely chopped

1 garlic clove, crushed

freshly grated nutmeg

6 eggs

1 tablespoon chopped herbs, such as coriander, parsley or chives, or a mixture

2 tablespoons freshly grated Parmesan cheese

200g fresh white crab meat

sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

Remove and discard the stalks from the spinach. Blanch the leaves in a large pan of boiling salted water for 1 minute, then drain and refresh in cold water. Squeeze out the excess water, chop the spinach roughly and set aside.

Heat 1 tablespoon of the olive oil in a pan, add the onion and garlic and cook over a moderate heat for 5–10 minutes, until soft. Stir in the spinach and season well with salt, pepper and nutmeg, then remove from the heat.

Lightly beat the eggs in a bowl. Mix in the spinach and onion, plus the herbs, Parmesan, crab meat and some seasoning.

Heat the remaining olive oil in a non-stick frying pan over a high heat for 2 minutes. Add the frittata mixture and reduce the heat to medium. Cook until the frittata is set underneath and still slightly runny on top, running a spatula around the sides to make sure it is not sticking. Place the pan under a hot grill for 1 minute to cook the top. Slide the frittata out of the pan and leave to cool for about 10 minutes, then cut it into wedges to serve.

Sesame Coconut Fish (or Chicken) with Chilli Spinach

Firm white fish such as halibut work best in this quick, light dish.

Serves 4

4 × 175g pieces of white fish fillet, skinned (or 4 chicken breasts,

skinned)

3 tablespoons sunflower oil

1–2 red chillies, deseeded and finely chopped

2.5cm piece of fresh ginger, finely grated

300g spinach, stalks removed

sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

For the sesame coconut crust:

1 teaspoon brown sugar

2 teaspoons oyster sauce

1 egg, lightly beaten

2 tablespoons sesame seeds

2 tablespoons desiccated coconut

1 garlic clove, crushed

2 tablespoons chopped coriander

Mix all the ingredients for the crust together and spread them over the fish fillets. Chill for a few hours to firm up.

Heat 2 tablespoons of the sunflower oil in a large, ovenproof frying pan. Place the fish in the hot oil, crust-side down, and cook over a medium heat for about 5 minutes, until the crust is golden brown. Carefully turn the fish over with a spatula, transfer the pan to an oven preheated to 200°C/Gas Mark 6 and bake for 4–5 minutes (10 minutes for chicken), until cooked through.

Meanwhile, heat the remaining sunflower oil in a frying pan, add the chilli and ginger and cook for 2 minutes. Turn up the heat, add the spinach and cook, stirring vigorously, until wilted. Season to taste. Serve the fish on the spinach.

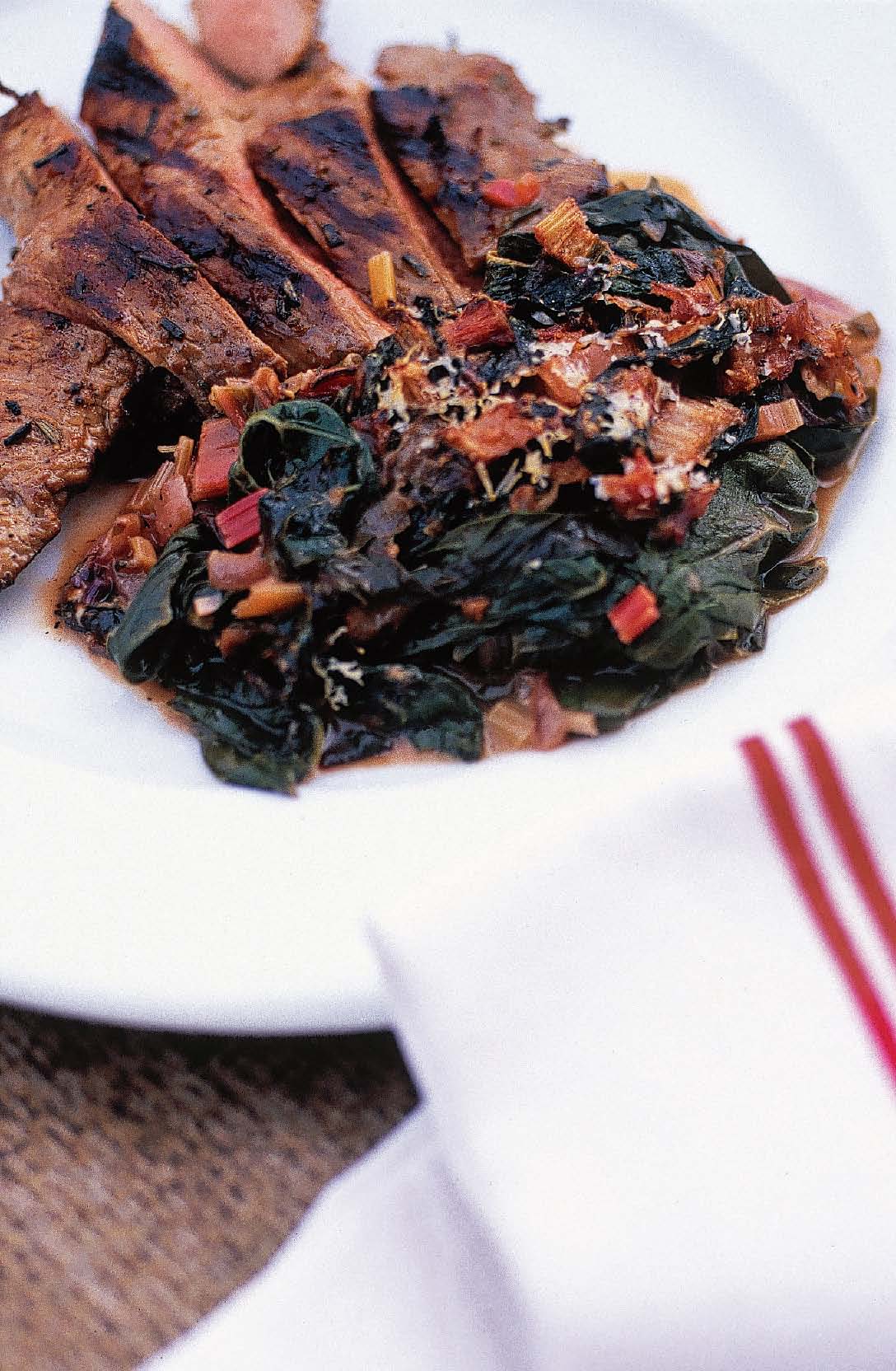

Grilled Leg of Lamb with Swiss Chard and Anchovy Gratin

This is a dish we often serve in the Field Kitchen. The gratin is based on one in the lovely book A Table in Provence, by Lesley Forbes (Webb & Bower, 1987). Jane doesn’t need much persuasion to add anchovies to anything, but the chard and anchovy work particularly well together.

Serves 6

6 garlic cloves, crushed

2 tablespoons chopped rosemary

a good pinch of freshly ground black pepper

3 tablespoons lemon juice

4 tablespoons olive oil

1 leg of lamb, weighing about 2kg, skinned, boned and butterflied (you could ask your butcher to do this)

For the stock:

juice of 1/2 lemon

a splash of white wine

1 teaspoon sugar

1 bay leaf

a sprig of thyme

For the gratin:

2 bunches of Swiss chard (about 500–600g)

a large knob of butter

1 onion, chopped

3 garlic cloves, crushed

6 anchovies

1 tablespoon plain flour

1 tablespoon freshly grated Parmesan cheese

freshly ground black pepper

Mix together the garlic, rosemary, pepper, lemon juice and olive oil to make a marinade. Place the lamb in a large dish, pour over the marinade and leave at room temperature for 8 hours or overnight, turning the meat occasionally.

To make the stock, put all the ingredients in a pan with 500ml of water, bring to the boil and simmer for 20 minutes. Strain and set aside.

To make the gratin, separate the chard leaves from the stalks and blanch them in a large pan of boiling salted water for 1 minute. Drain well, refresh under cold running water, then squeeze out excess water. Set aside.

Cut the chard stalks across into 5mm strips. Bring the stock to the boil, add the chard stalks and simmer gently for 5 minutes. Drain the stalks and set aside, saving the stock for later.

Heat the butter in a pan, add the onion and cook gently for 15 minutes, until soft. Add the garlic and cook for a few more minutes. Remove from the heat and add the anchovies, stirring until they dissolve into the mixture. Return to the heat and stir in the flour to make a roux. Cook very gently for 5 minutes. Slowly stir in the reserved chard stock until you have a thick sauce. Simmer for about 5 minutes.

Stir the chard stalks and leaves into the sauce, together with the grated Parmesan and some black pepper. Transfer the mixture to a gratin dish and bake in an oven preheated to 160°C/Gas Mark 3 for about 20 minutes, until golden.

Remove the lamb from the marinade. Preheat a ridged griddle pan or a large, heavy-based frying pan and cook the lamb for 2 minutes on each side, until browned. Transfer to a roasting tray and finish off in the oven at 200°C/Gas Mark 6 for a few minutes, depending on how pink you like your lamb. Leave to rest for about 10 minutes, then serve with the gratin.

Swiss Chard and Onion Tart

We started serving this as a vegetarian option in the Field Kitchen and it is so popular that we try to make sure everyone gets a slice now. The recipe is not set in stone. Consider the base as a canvas: you can add what you like (within reason). Try a few chopped anchovies or some mushrooms sautéed with thyme. You could even crack a couple of eggs on before baking.

Serves 4

1 quantity of Shortcrust Pastry (see For the shortcrust pastry)

50g butter

3 small onions, finely sliced

leaves from 1 sprig of thyme

300g Swiss chard

10 olives, chopped

1/2 tablespoon freshly grated Parmesan cheese

3–4 tablespoons crème fraîche sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

Roll out the pastry on a lightly floured surface into a rough circle (or actually any shape – this tart is very rustic, so the less uniform, the better). Place on a baking sheet, prick with a fork in several places and chill for 15 minutes. Place in an oven preheated to 200°C/Gas Mark 6 and bake for 10–15 minutes, until golden brown.

Heat the butter in a pan, add the onions and thyme and cook gently for about 10 minutes, until soft but not coloured.

Meanwhile, separate the chard stalks from the leaves and chop both leaves and stalks roughly, keeping them separate. Add the stalks to a pan of boiling salted water and cook for 2–3 minutes, until tender. Remove the stalks with a slotted spoon and set aside. Add the leaves to the boiling water and blanch briefly. Drain well, refresh under a cold tap and then squeeze to remove as much water as possible.

Add the chard stalks and leaves to the onions and reheat gently. Season to taste and mix well. Spread the mixture over the pastry base and sprinkle with the chopped olives, Parmesan and a few blobs of crème fraîche. Bake in an oven preheated to 190°C/Gas Mark 5 for about 15 minutes, until lightly browned.

Easy ideas for spinach and chard

♦ Cook spinach or chard leaves in boiling water for 1 minute, then drain, refresh in cold water and drain again. Squeeze out all the liquid. Fry some sliced garlic in olive oil until soft, add the spinach or chard and toss with raisins or toasted pine nuts. Season and serve.

♦ Mix 200g cooked chopped spinach or chard with 1 egg, 200ml double cream, 1 tablespoon of grated Parmesan and some seasoning. Bake in a gratin dish or in a pastry case (see Sorrel Tart, Sorrel and Onion Tart) at 150°C/Gas Mark 2 for about 25 minutes, until just set.

♦ Dress cold cooked spinach with pomegranate juice and seeds. Serve as part of a mezze or with grilled fish.

♦ For a quick soup, cook sliced spinach in a little butter, then add just enough milk and stock to cover and bring to the boil. Season well with salt, pepper and nutmeg, sprinkle with grated Parmesan and serve over toasted bread in a bowl.

See also: