2

ORDERLY: THE CHARM OF CRYSTALS

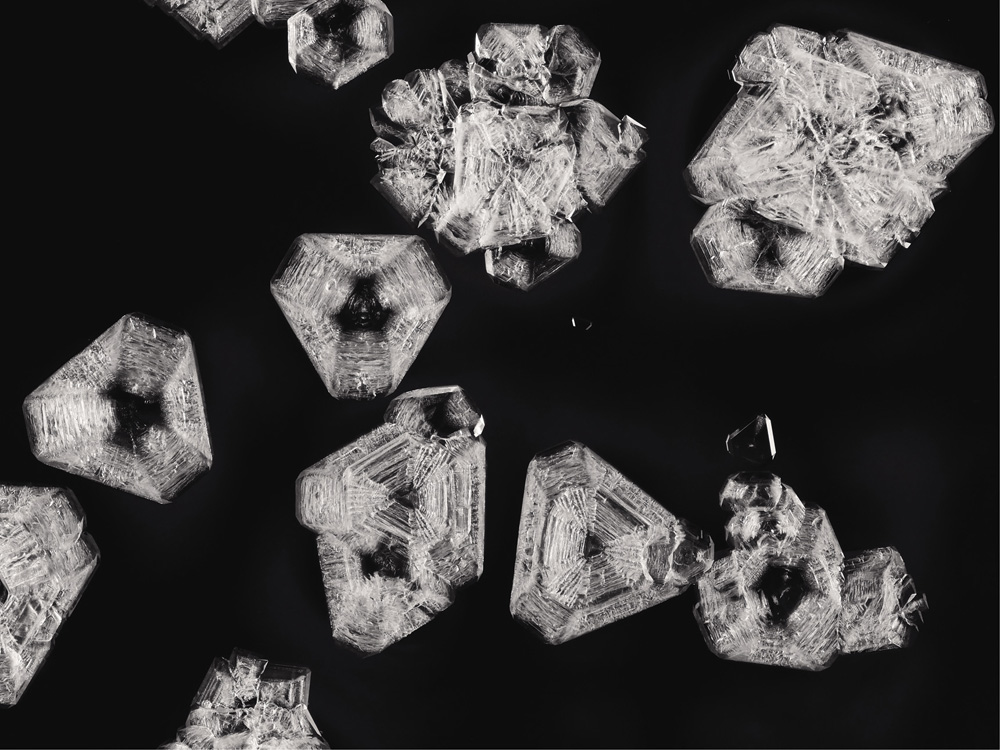

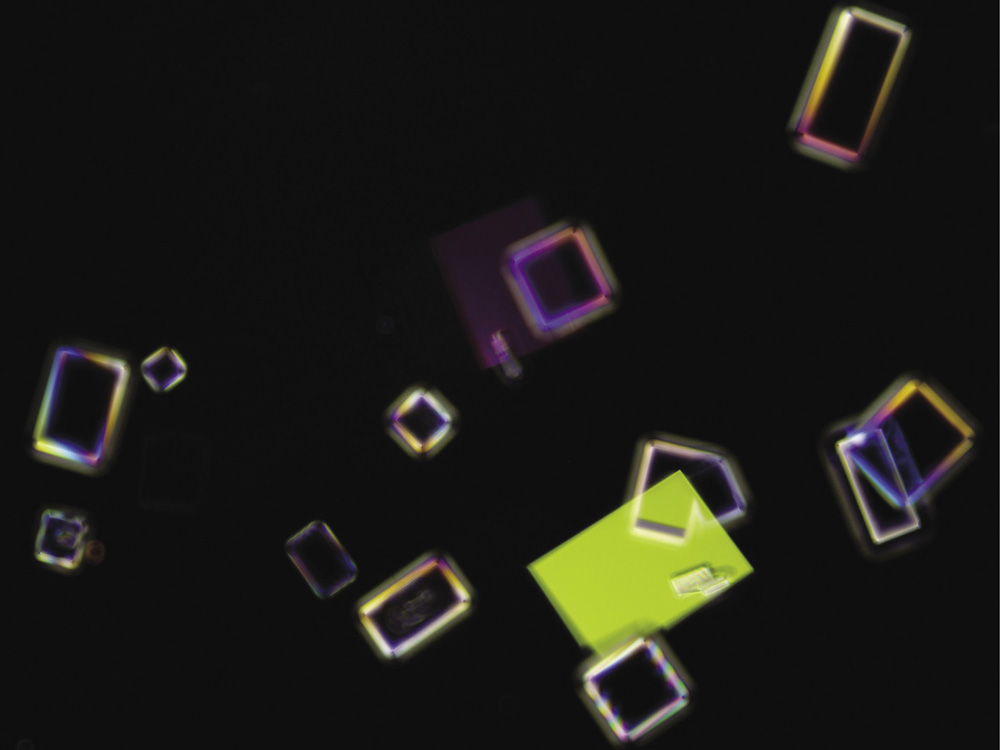

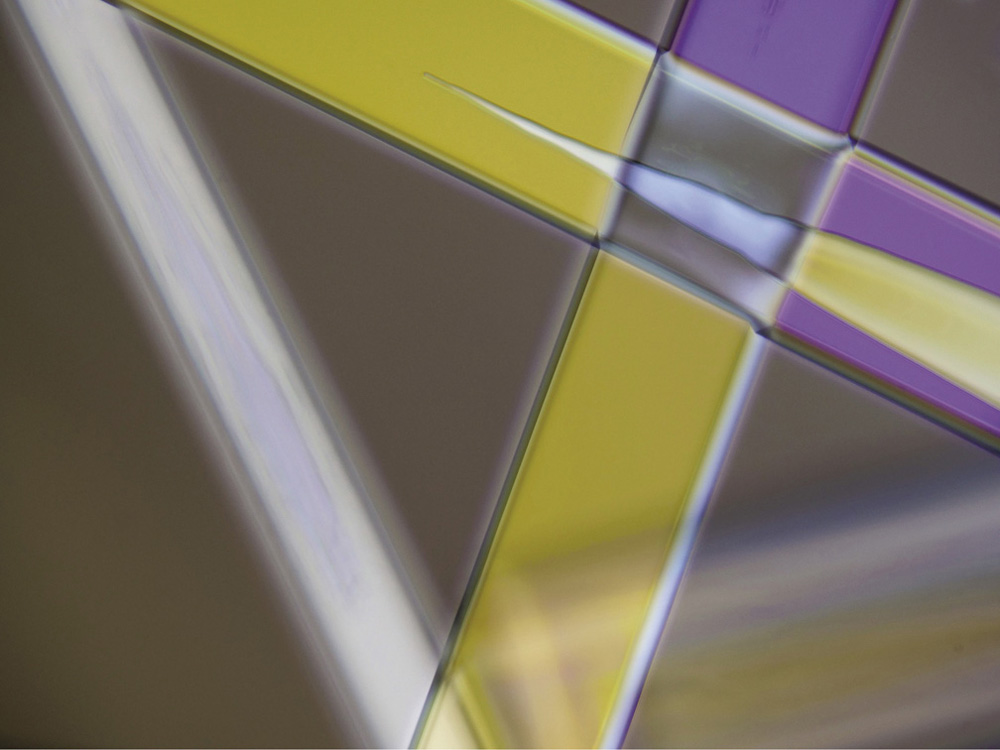

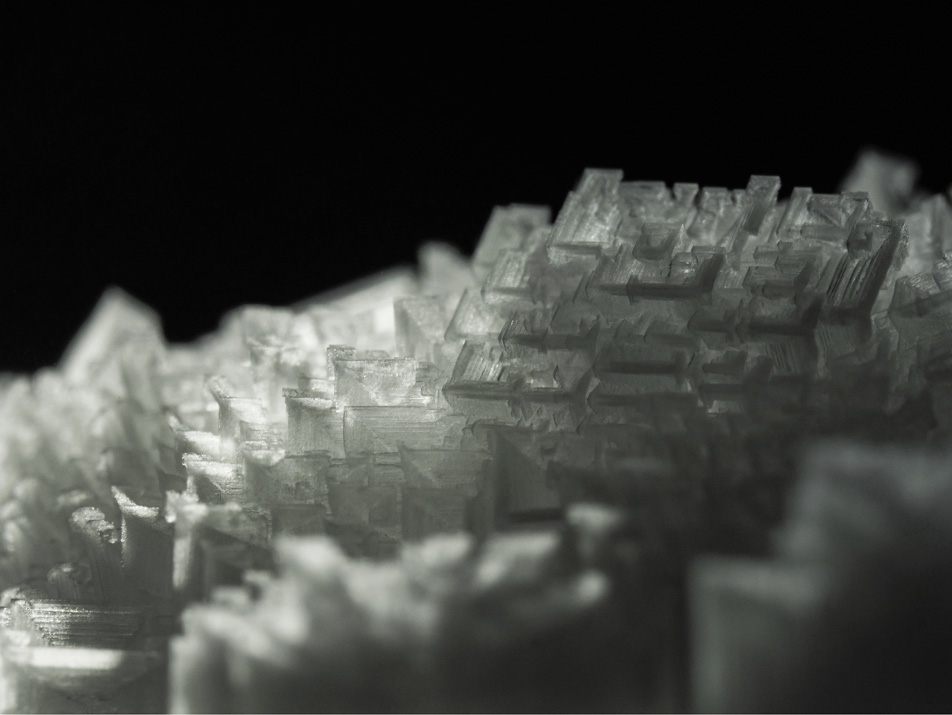

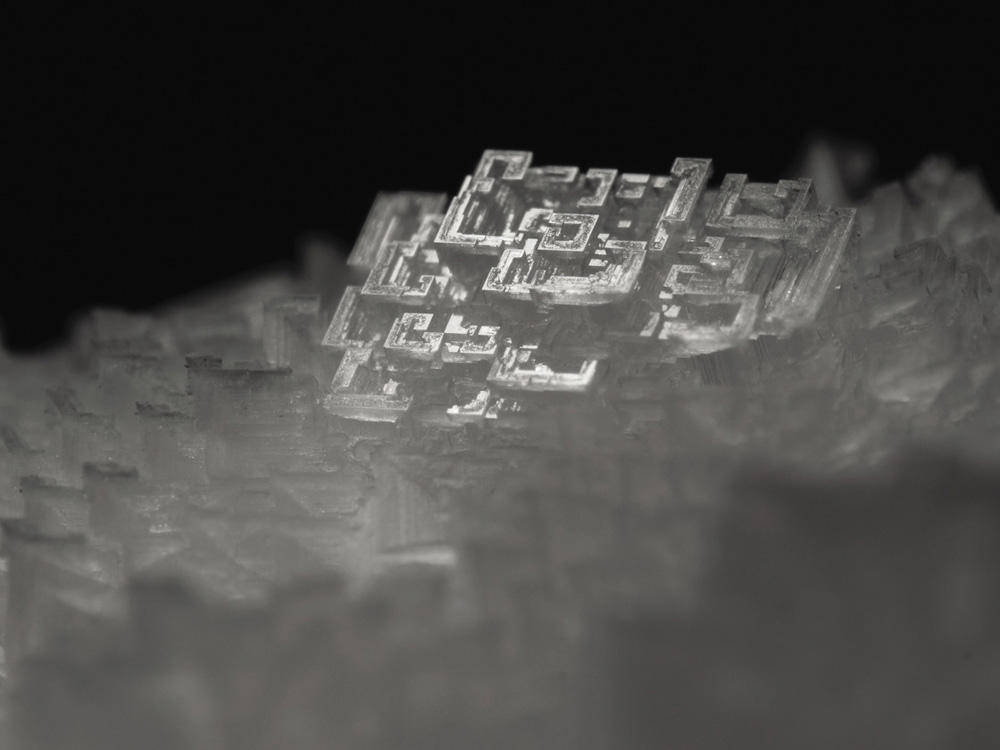

Crystals of sodium chloride (table salt) under polarized light

Crystals cast a spell. There's an otherworldly quality to their sparkle, their peculiarly geometric, prism-like shapes, the translucent colors that seem to shift and elide deep in the interior. In the Bible they may represent purity or faith; the book of Revelation says of the city of New Jerusalem that appears after the Second Coming of Christ that “the light thereof was like to a precious stone, as to the jasper stone, even as crystal.” In the twelfth century, the French abbot Suger asserted that the divine light of God was like the gleam of gemstones, and that contemplating jewel-encrusted objects in his church at Saint-Denis near Paris would draw worshipers closer to God. Perhaps, though, he was merely seeking to justify a love of the way they looked.

Crystals were once widely thought to have special powers: medical, magical, and spiritual. Emeralds were believed to restore tired eyes, amethyst could ward off hailstorms and locusts, and green jasper could make you invisible. Needless to say they do nothing of the sort, and there is no evidence that crystals have healing properties despite the continuing popularity of that notion. Yet it is hardly surprising that these things were once believed, or that some vestige of those ideas persists. The sheer beauty of crystals is a balm in itself. Why look for more magic than that?

If, in times gone by, you shared the suspicion of the ancient Greek philosopher Plato that nature is governed by geometry, then the shapes of crystals seemed to offer confirmation. Why otherwise would they develop those flat, smooth planes, intersecting at crisp, perfect angles? Why would all crystals of table salt (the compound chemists now call sodium chloride) choose to grow as cubes, while quartz (silicon dioxide) forms prismatic columns tipped with pyramids?

Pondering this question in the early seventeenth century, the German astronomer and mathematician Johannes Kepler was forced to suppose that nature possesses what he called a “formative faculty,” with a preference for geometric order—and that “she knows and is practiced in the whole of geometry.”

“The sheer beauty of crystals is a balm in itself. Why look for more magic than that?”

Today we have no need to fall back on such a vague, mystical idea—but that is partly thanks to Kepler himself. In contemplating the shapes of snowflakes and the cause of their “six-cornered” pattern, he wondered if the geometrical appearance might stem from a regular packing together of spherical “globules” of congealed water (in other words, ice), like the stacks of cannonballs commonly found on the decks of galleons.

Such arrangements are perhaps more familiar today from the packing of snooker or pool balls in the triangle at the start of a game. Fifteen of them fit exactly, and the balls in the center are each surrounded by exactly six others in a hexagonal arrangement.

You can place another layer of balls on top of the fifteen in the triangle, each ball resting in the dip between the three below it. Only ten balls will fit in that layer. You can add a third layer in the same way—for which there are now just six spaces. Atop that, add another three, and finally a lone ball at the pinnacle.

What you have then is a pyramid of balls, with each of the sloping faces making up another triangle. Flat faces, equal angles, sharp corners, geometric perfection: it's like a crystal. And that indeed is what crystals are like—Kepler was right, although in place of his “globules” the spheres are atoms, and each crystal face holds countless trillions of them.

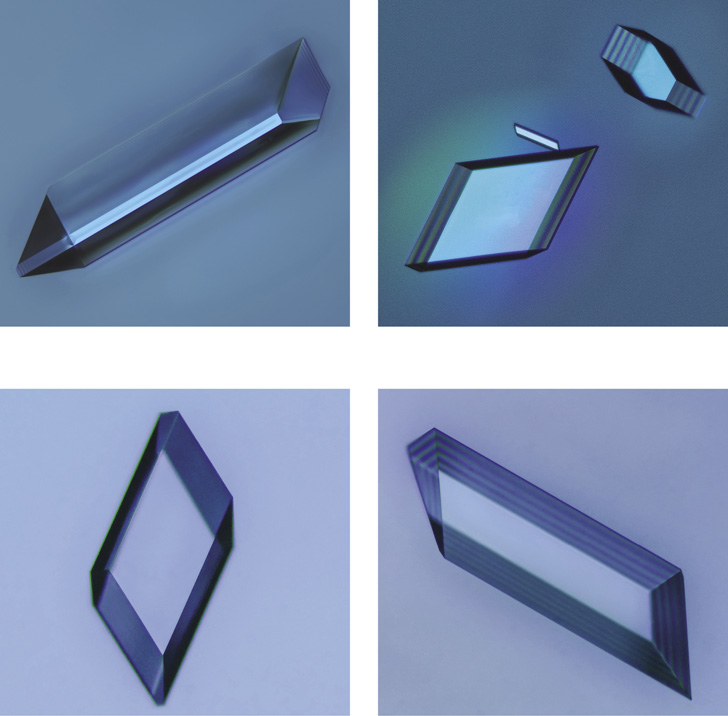

This arrangement of spheres is called hexagonal close packing, and it is the most efficient way of stacking them, leaving the least amount of empty space in between. But there are other ways they can pack regularly too, for example in square instead of hexagonal formation. That creates cube or cuboid shapes with square or rectangular faces. In the scientific study of the atomic-scale structure of crystals, a regularly repeating and geometric configuration like these is called a lattice. There are precisely 14 different types of regular lattice into which objects may be packed in three dimensions: 14 types of symmetry. All crystals have structures corresponding to one of these lattices.

Each crystal structure consists of a particular arrangement of its component parts that repeats again and again, like the stacking of boxes in a warehouse. That basic building block of the structure is called the unit cell: a “box” within which the atoms that make up the crystal are always arranged in the same pattern. Often the shape of the crystal itself echoes the shape of its unit cell: the cubic crystals of table salt, for example, contain cube-shaped unit cells made up of sodium and chloride atoms (actually ions, because they are electrically charged; see the appendix for an image of this structure).

The smooth facets of natural minerals and gems are the planes made by countless atoms, packed and stacked with mathematical precision. Each unit cell of a crystal may contain many atoms. For sodium chloride there are precisely four atoms of sodium and four of chlorine for each unit cell. Some crystals can have very complicated unit cells. The minerals called zeolites, for example, have their atoms (typically those of silicon, aluminum, oxygen, and other metals) arranged into rings and cages, creating molecular-scale channels that thread through the material like a microscopic version of the catacombs beneath Paris. Molecules adopt crystalline states by stacking together in regular arrays—the molecules themselves might have irregular, unsymmetrical shapes, but they will fit together in an orderly manner rather like cars in a car park. Here the unit cell becomes a bit like the rectangular parking spaces: they are organized in a simple, geometric grid, even though what's inside them is covered in knobs and bumps and curved surfaces. As a result, the overall crystals that can be seen by the naked eye look as regular and geometric as ever, despite the lumpy irregularity of their molecules.

“The smooth facets of minerals and gems are planes made by countless atoms packed with mathematical precision.”

Although the ancient Greeks had no comprehension of the atomic origins of crystalline form, they had a pretty good sense of how crystals are formed. Their word krystallos comes from kryos, meaning cold, and systellein, to draw together. Crystals are drawn together by the cold—think of ice, which is the crystal formed when water freezes. The Roman writer Pliny said in his great compendium Natural History in the first century AD that “rock crystal” (a common name for quartz) was “a kind of ice . . . formed of moisture from the sky falling as pure snow”—that is, a kind of ice that is frozen forever.

He was wrong about that—quartz isn't ice at all, but is made from atoms of silicon and oxygen. (To be honest, Pliny was wrong about a lot of things. He thought, for example, that soaking a diamond in goat's blood makes it brittle, which proves that he never actually tried the experiment—he just read the idea somewhere. The moral is that you shouldn't take someone else's word for it, but check it out for yourself. That's the hallmark of science.)

But it's true that crystals can be made by cooling. That's how chemists often make them today. They might dissolve a chemical in a warm liquid solvent and then let it cool, whereupon crystals can start to form.

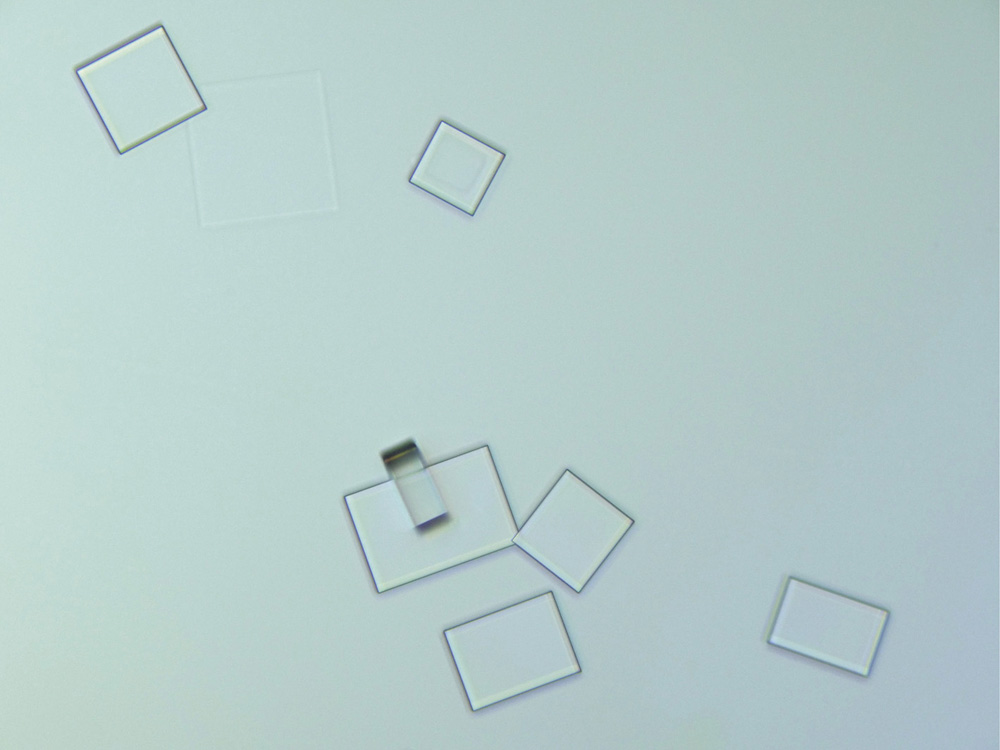

Why do this? Not simply to make something lovely, although crystals are often that. In chemistry, once you've used chemical reactions to synthesize the compound that you want, it's often a smart move to make crystals of it. There are two reasons for this. The first (we'll come to the second eventually) is to purify the substance. As the crystal forms, the molecules pack together tightly, leaving no spaces for ones that don't fit—such as impurities in the solution. So even if the solution does contain small amounts of impurities, the crystals that grow within it will generally be more pure.

Crystallization is a simple, handy way of purifying a chemical. Often a chemist might conduct this purification process repeatedly: make a crystal, dissolve it again in a hot solvent and let it cool to recrystallize, then do it again. Each time the crystals get a little more pure.

Let's think about that process of crystallization more carefully. It's one thing to explain the geometry of crystals in terms of the orderly arrangement of their atoms, but it's quite another to explain how atoms drifting about randomly in solution acquire this regimentation when they get together to make a solid.

Crystals assemble themselves, as if each atom knows where it belongs. Needless to say, atoms don't really possess any such insight. But nature supplies the larger vision needed for this orderliness, in the form of energy and stability. Processes in nature tend generally to happen in the way that confers greatest stability: that's why water runs downhill. (We'll examine this criterion a bit more closely later in the book.) The self-assembly of crystals is like a downhill process too: as atoms or molecules get added to a crystal, they settle into the energetically most stable positions. That might involve a bit of adjustment—an atom settling on the surface of a growing crystal might not lodge where it first touches, but will wander on the surface until it finds a comfortable place to rest, dictated by the positions of atoms already in place in the crystal lattice. Think of it like settling ping-pong balls into some gigantic egg box: with a gentle shake, the balls will eventually all sit in the dips, making orderly ranks.

Nevertheless, mistakes do occur in the way atoms are packed in crystals. These are called defects, as for example where two rows of atoms in the lattice merge into one. Nothing's perfect. Defects can create points of weakness in a crystal, while in metals their reshuffling through the lattice gives the material its ductility, whereby the material bends rather than snapping when deformed.

Why do crystals appear in the first place in a solution when it cools? This happens because, in general, a warm liquid can hold more dissolved substance than a colder one. If the solution is very dilute, changing the temperature doesn't make much difference. But if it is concentrated to the point where no more of the substance will dissolve—what scientists call a saturated solution—then cooling will compel some of the substance to solidify. A solution can also become “supersaturated” and apt to crystallize if some of the liquid evaporates, because this means that the remaining solution is more concentrated.

All the same, crystallization in a supersaturated solution has to start somewhere: the atoms have to get together and start growing into a crystal. Because the motions of dissolved atoms and molecules are random, as they are buffeted from all directions by the molecules of the liquid, the formation of this initial seed from which a crystal will grow is a matter of chance. However, once a seed grows bigger than a certain critical size, it snowballs—it is more likely to keep growing than to fall apart again—and crystal growth is under way. This process of crystal nucleation is somewhat analogous to the nucleation of bubbles that we discussed in the previous chapter.

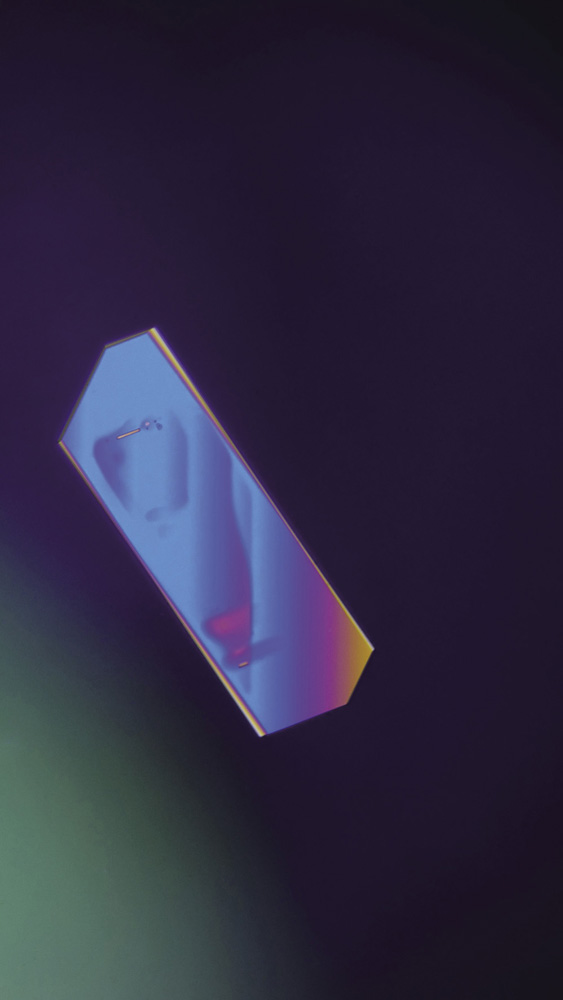

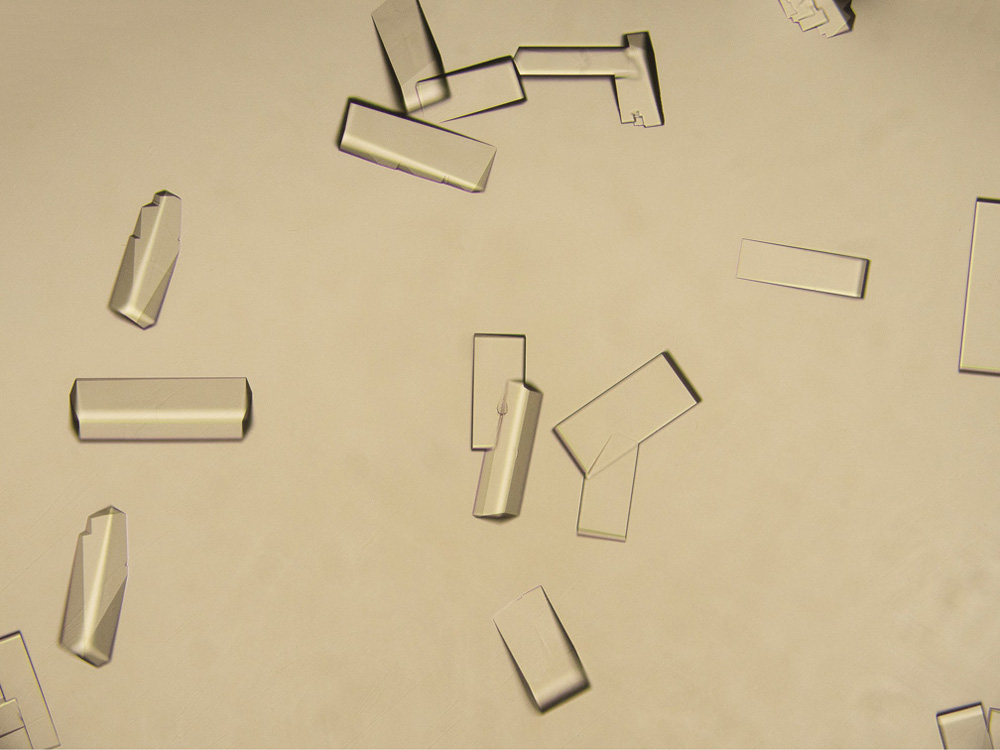

The second reason why chemists grow crystals is so they can figure out what kinds of atoms and molecules a compound contains—to check whether they have made what they think and hope they have made, or to work out the shapes of the molecules.

It's possible to do this using X-rays, which are electromagnetic waves like a very high-energy form of light (see chapter 8). Crystals contain stacked layers of atoms, and X-rays can be reflected from successive layers as if from mirrors. Because the wavelength of X-rays—the distance between wave peaks—is typically similar to the distance between the atomic layers, the rays reflected from one layer can interfere with those from the next. Their peaks might coincide, making the rays brighter, or a peak might coincide with a trough, canceling them out. The result is that the X-rays reflected from a crystal and impinging on a detector register as a pattern of bright and dark spots. This is an encoded image of the arrangement of the atomic layers.

By mathematical analysis of this so-called X-ray diffraction pattern, it's possible to figure out where the atoms sit in relation to one another. This technique, called X-ray crystallography, was devised in the early 1910s, largely by the father-and-son team William and Lawrence Bragg; the younger Bragg was at the time still an undergraduate at Cambridge. Their work was so immediately useful and important that the Braggs were awarded a Nobel prize in 1915.

The Braggs demonstrated their new method on crystals of salts and gemstones. One of their first subjects was diamond: a crystal form of pure carbon. Their fine specimen came from the mineralogical collection at Cambridge, despite the fact that the Professor of Mineralogy William Lewis had strictly forbidden any loans of the precious item. The collection's demonstrator, Arthur Hutchinson, risked his job to lend the gem to the Braggs behind Lewis's back. “I shall never forget Hutchinson's kindness in organizing a black market in minerals to help a callow young student,” Lawrence Bragg later wrote. “I got all my first specimens and all my first advice from him and I am afraid that Professor Lewis never discovered the source of my supply.”

X-ray crystallography supplied scientists’ first glimpse into the atomic world itself. It gave them a way to deduce the shapes of molecules: how their atoms are joined together in three dimensions. Researchers were particularly eager to discover the shapes and structures of biological molecules, since that might reveal secrets about how they do their jobs in living cells. Take the protein molecule hemoglobin, which ferries oxygen around in red blood cells. The Austrian-British scientist Max Perutz and his coworkers began to study its structure in the 1950s, and by 1960 they had mapped out a still rather fuzzy sketch of it. Like all proteins, hemoglobin is a chainlike molecule called a polypeptide folded up into a specific shape. Proteins contain hundreds or even thousands of atoms, and figuring out where they all sit from the patterns of X-rays bouncing off their crystals is a tremendously challenging task.

“X-ray crystallography supplied scientists’ first glimpse into the atomic world.”

Crystallography has garnered more Nobel prizes than any other scientific field, testifying to its importance in physics, chemistry, biology, mineralogy, and beyond. Perutz won a Nobel in 1962; two years later one was given to Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin, who in the 1940s and 1950s pioneered the use of the method for molecules more complex in structure than many would have dared contemplate. In 1949 she published the molecular structure of penicillin, one of the first antibiotics that were transforming healthcare by suppressing bacterial diseases and infections after injury or surgery. Her solution to the structure of vitamin B12 in 1954 secured her reputation as the doyenne of the craft of crystallography, and she studied the hormone insulin for over 30 years, finally cracking its structure in 1969.

Probably the most famous and momentous of Nobel-winning crystal structures is that deduced in 1953 by James Watson, Francis Crick, Maurice Wilkins, and Rosalind Franklin: the double helix of DNA. Franklin died of cancer before the Nobels were awarded in 1962—otherwise one fears how, in an age that tended to marginalize women in science (a tendency still not fully expunged), the committee would have dealt with the restriction to a maximum of three recipients.

DNA is not a protein; it belongs to a class of biological compounds called nucleic acids. It is the molecule that encodes the genes which direct the development of all living things, and which are inherited from parents to offspring. Each DNA molecule is made up of two separate strands, which wind around one another in helices and are “zipped” together by weak chemical bonds that span the strands. “Our structure is very beautiful,” Crick wrote to his son just after he and Watson had figured out how it all fitted together. To do that, they relied on the X-ray diffraction patterns made by Franklin and her student Raymond Gosling, working with Wilkins, from crystals of the molecule. The paired-up strands of DNA immediately suggested to Crick and Watson how genes could be copied when cells divide: each strand can separate and act as a template on which a new strand can be assembled. (That process depends on the help of a special DNA-replicating protein enzyme.) In this way, the crystal structure unlocked one of the greatest secrets of biology: how genetic information can be passed on to progeny, which is central to the process of evolution.

It's because crystals are so useful for understanding the structures of complicated molecules and compounds that so much effort goes into making them. But this is something of a black art. Just as some people have “green fingers” that seem able to coax seeds into plants, so some seem inexplicably adept at producing crystals where others fail. Crystals often need a “seed” to get them started: to trigger the process of nucleation. Chemistry students learn that scratching the side of their beaker with a glass rod might be all that's required to spark the appearance of crystals in the solution. The scratch, too small to see, gives atoms and molecules something to cling to, bringing them together to start the growth process. A fleck of dust might do the trick too. Or it can happen by sheer, happy accident. British chemist David Jones once recalled that “a new compound of mine once refused to crystallise until I accidentally spilt some in the laboratory fridge—something seeded it, and my spillage crystallised!” Some methods for triggering crystal growth these days are more dependable and high-tech; a team in Edinburgh found in 2009 that very short pulses of laser light can do it, allowing them to write patterns in crystals within slabs of gel.

“Making crystals is something of a black art: some people seem inexplicably adept at producing them where others fail.”

Growing protein crystals is a particularly desirable goal. But it's hit-and-miss—some proteins seem frustratingly stubborn in their refusal to crystallize. For other proteins, the problem is that they won't dissolve in water in the first place, because they're “designed” (by evolution) to be soluble instead in the fatty cell membrane. Scientists are working out how to encourage such membrane proteins to line up in the orderly arrays needed for crystallography. They are also developing ever brighter sources of X-rays, for with stronger beams it becomes possible to collect enough reflected X-rays for crystallography even from a very tiny crystal: the task of crystal-growing is then less challenging. In fact, you don't necessarily need crystals at all. Using the brightest of today's X-ray beams, scientists are approaching the point where they can deduce molecular structures just from the X-rays scattered off single molecules fired into the beam. A capability like that could revolutionize the study of molecular structure.

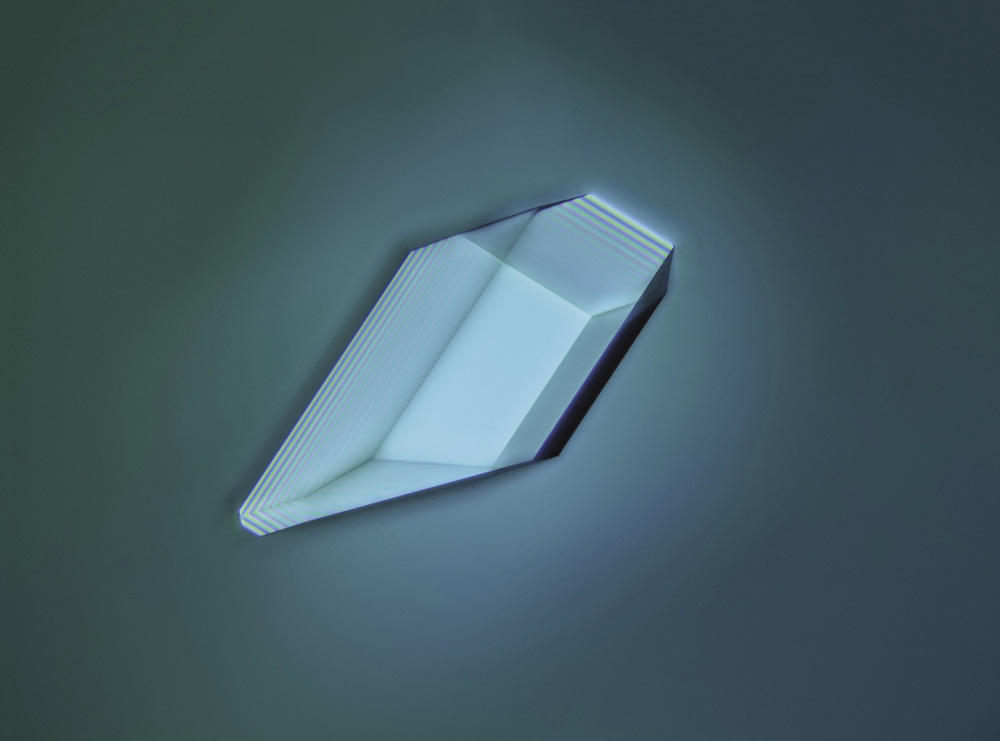

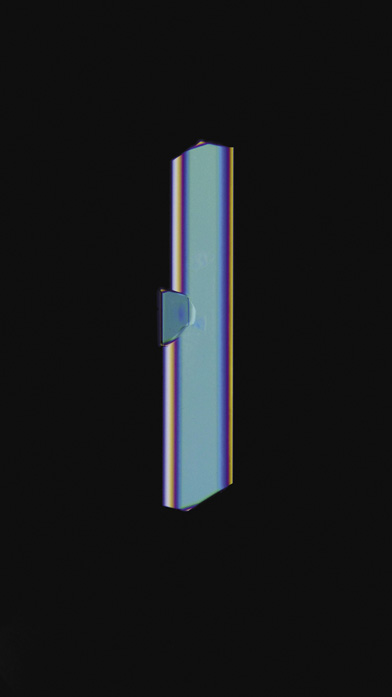

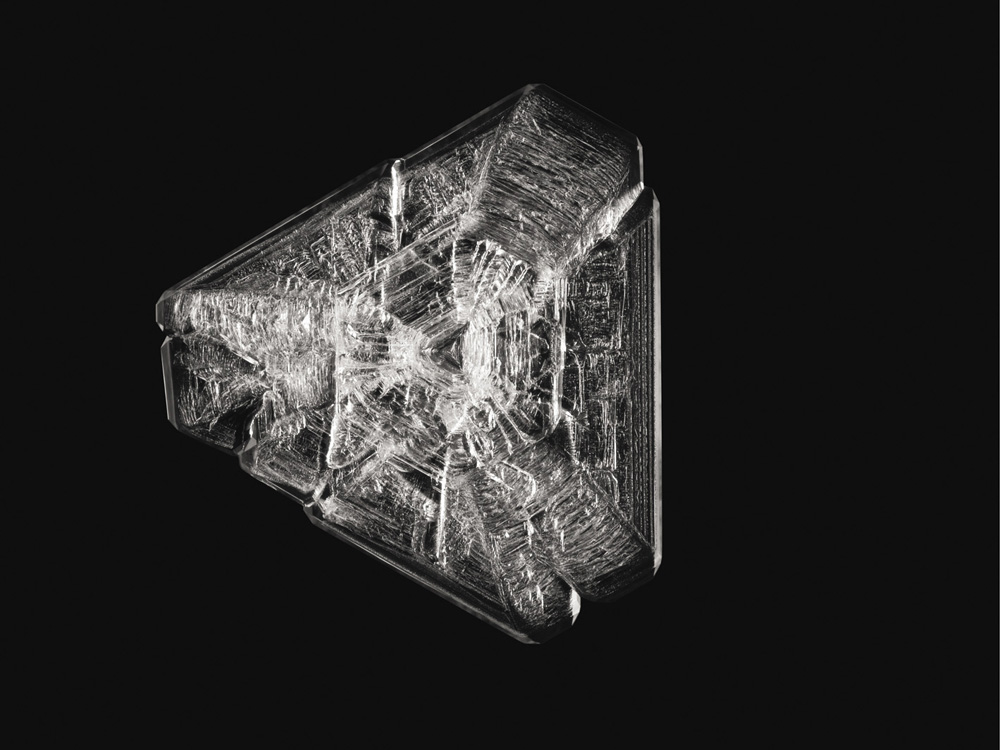

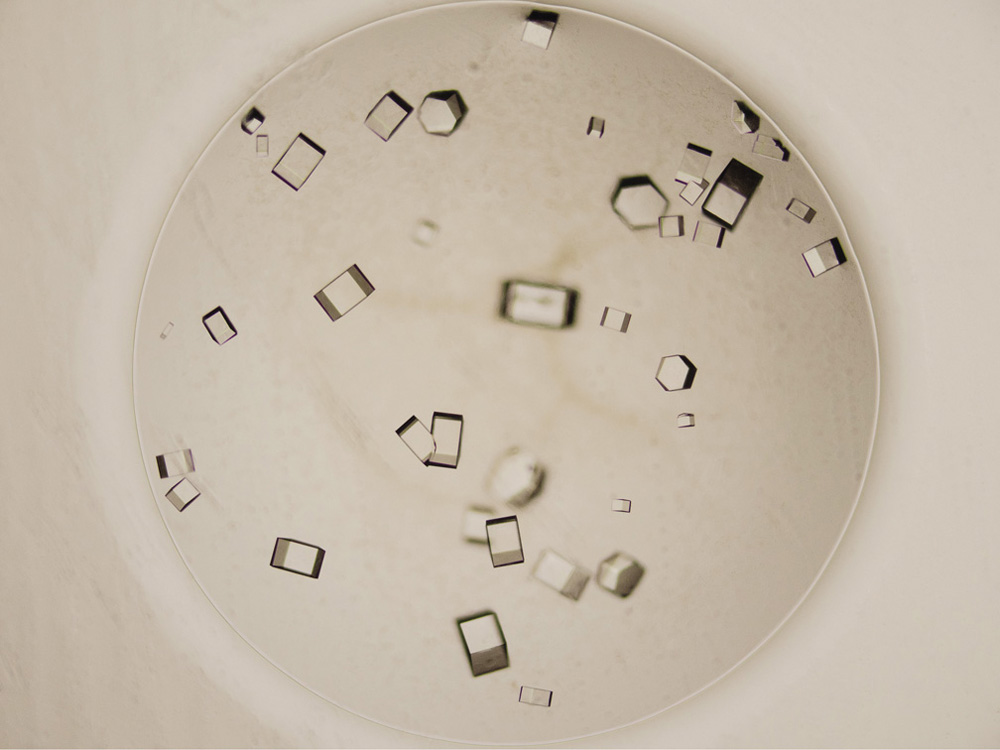

Protein crystals (sample provided by Jie Zhu, graduate student at the Laboratory of Biochemistry and Structural Biology, University of Science and Technology of China)

“Where once humans sought to exploit the riches underground, now we want to preserve them.”

What happens in the test tube or beaker as crystals grow also occurs deep underground as minerals form. Water saturated with dissolved metal salts creeps through cracks and fissures in the rock, heated by the innate warmth of the planet's interior or by buried reservoirs of hot magma welling up from close to the fiery core. As they cool, these salty fluids release their bounty as minerals and gems: “solidified juices” of the earth, as the sixteenth-century German authority on mining Georgius Agricola called them.

Mining was a lucrative business by Agricola's time. His influential treatise on the subject, De re metallica (1556), while presenting itself as a practical guide, is poetically evocative of the underground wonderland of the miner. The litany of mineral names alone conjures up subterranean marvels: azure, chrysocolla, orpiment, realgar. Some of these minerals are so intensely colored that they were used, finely ground, as artists’ pigments. One, called “zaffre” in Agricola's time, was rendered deep blue by the cobalt it contained—the mineral name is a form of “sapphire,” though true sapphires get their blue from another chemical source. The name of that metallic element cobalt, meanwhile, comes from the German word kobelt, meaning gnome or goblin: it was widely thought even in Agricola's time that these creatures guarded the hidden caverns where minerals were to be found, and would torment miners who came looking for them. The poet John Keats echoed that old belief in his complaint in the early nineteenth century that science was destroying the wonder and mystery of the world: he argued that it would “empty the haunted air, and gnomed mine.”

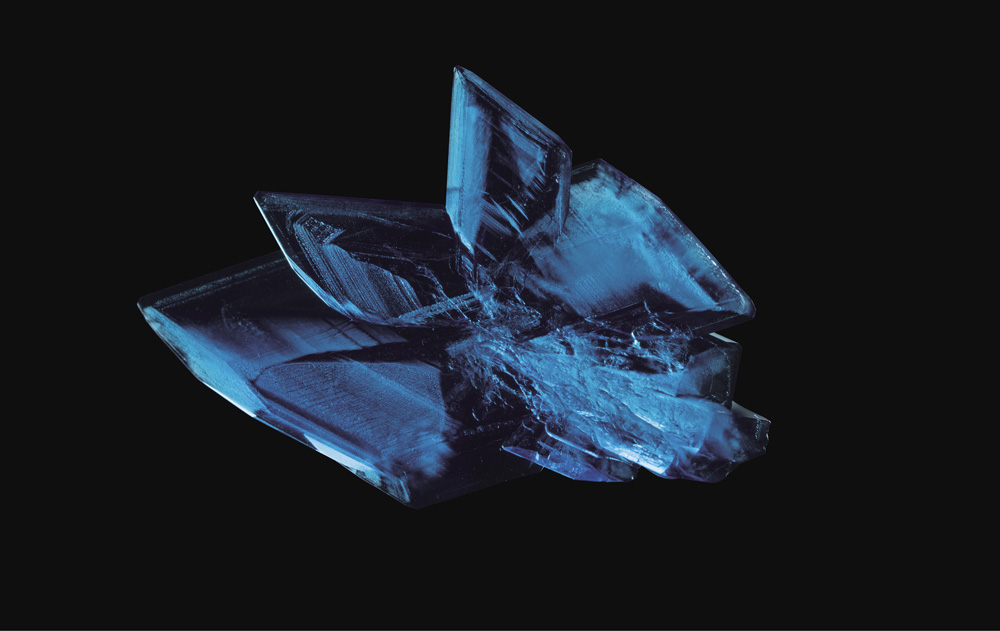

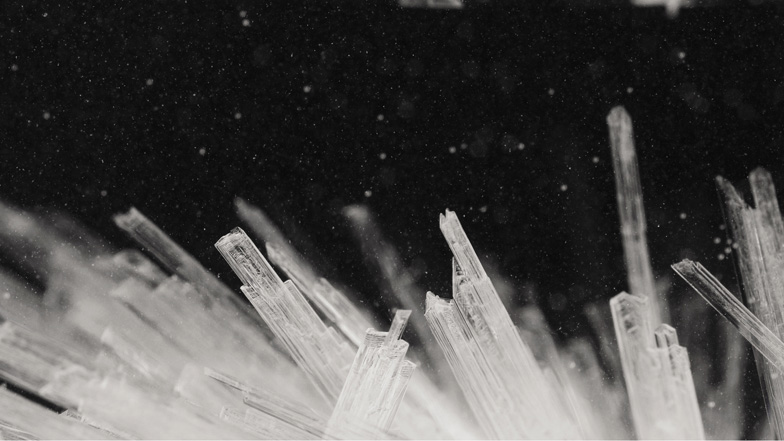

There was no need for Keats to fret. Under-standing how mineral crystals grow underground from hot, metal-rich fluids is unlikely to rob anyone of the wonder that lies in store if they are lucky enough to get a rare glimpse of the caves of Naica at Chihuahua in Mexico. These caverns house one of nature's most spectacular works of art: enormous crystals of the mineral gypsum (a form of calcium sulfate), precipitated from hot fluids over a period of thousands of years. The caves are part of a lead and silver mine that has operated since the early nineteenth century; the first caverns containing these giant crystals were discovered during mining excavations in 1910. The gypsum crystals have grown into immense prismatic columns that bisect the space in near-transparent pillars up to eleven meters long and about a meter wide. Their luster in the illuminated cave is like frozen moonlight.

There are probably more caves within the tangled fault networks of the Naica system, perhaps with even bigger crystals. But to preserve these natural wonders, visitors are permitted to view the caves only in small groups, with permission and supervision of the mine management. Even then, scientific studies on the crystals have shown that they are at risk: no longer immersed in and supported by fluid within the drained mine, they could become weakened and cracked. Where once humans sought to exploit the riches underground, now we want to preserve them—a wish motivated (and rightly so) by reverence for their great beauty.

Crystals grow throughout the universe. Ice particles formed from water vapor in the upper atmosphere gather into clouds, called “noctilucent,” that glow with reflected sunlight in the twilit polar regions. On the frozen surface of the dwarf planet Pluto there are entire mountain ranges made from crystalline nitrogen.

Deep in the hot, dense interior of Saturn's atmosphere, meanwhile, carbon atoms are thought to be crystallizing constantly into tiny particles of pure diamond—perhaps a thousand tons of them every year. The planet 55 Cancri e, detected around a star 41 light-years away, might be especially rich in carbon, and around a third of its mass might be pure diamond.

These are seeds of order in an often turbulent and violent cosmos. When we watch crystals grow in the lab, we are seeing one of nature's universal acts of creation: atoms given collective form, an expression of nature's geometric dreams.

Further reading

- Carreño-Marquez, I. J. A., et al. “Naica's giant crystals: deterioration scenarios.” Crystal Growth and Design 18, 4611–4620 (2018).

- Ferry, G. Dorothy Hodgkin: A Life. London: Granta, 1999.

- García-Ruiz, J. M., et al. “Formation of natural gypsum megacrystals in Naica, Mexico.” Geology 35, 327–330 (2007).

- Hargittai, I., and M. Hargittai. Symmetry: A Unifying Concept. Bolinas, CA: Shelter, 1994.

- Jenkin, J. William and Lawrence Bragg: Father and Son. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Kepler, J. The Six-Cornered Snowflake. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Tatalovic, M. “Crystals grown in a flash.” Nature online news, 5 August 2009. https://www.nature.com/news/2009/090805/full/news.2009.801.html.

In the macrocosm, the beauty of chemistry arises before us as it does in the images of this book. In the microcosm, when we talk about elements as atoms we cannot perceive them visually. There are no microscopes that allow a detailed examination of atoms. But in this invisible substance is the whole essence of the structure of matter. Can we talk about the beauty or harmony of what we cannot see, and which has no smell, taste, color?

We can, probably, but only in our imagination. Aesthetics (or beauty, if you will) appears here with a deep knowledge of the subject. Its behavior is not described by Newtonian mechanics, but by quantum mechanics. There are no trajectories of movement, and time and space themselves are transformed. Everything is not the same as it is in the macrocosm. But beauty and harmony, as immaterial concepts, remain and acquire a new meaning. And they give us a sense of beauty that is no less than we perceive in these magical pictures from the macrocosm.

Joint Institute for Nuclear Research, Dubna, Russia