10

CREATIVE: THE PROFUSION OF PATTERNS

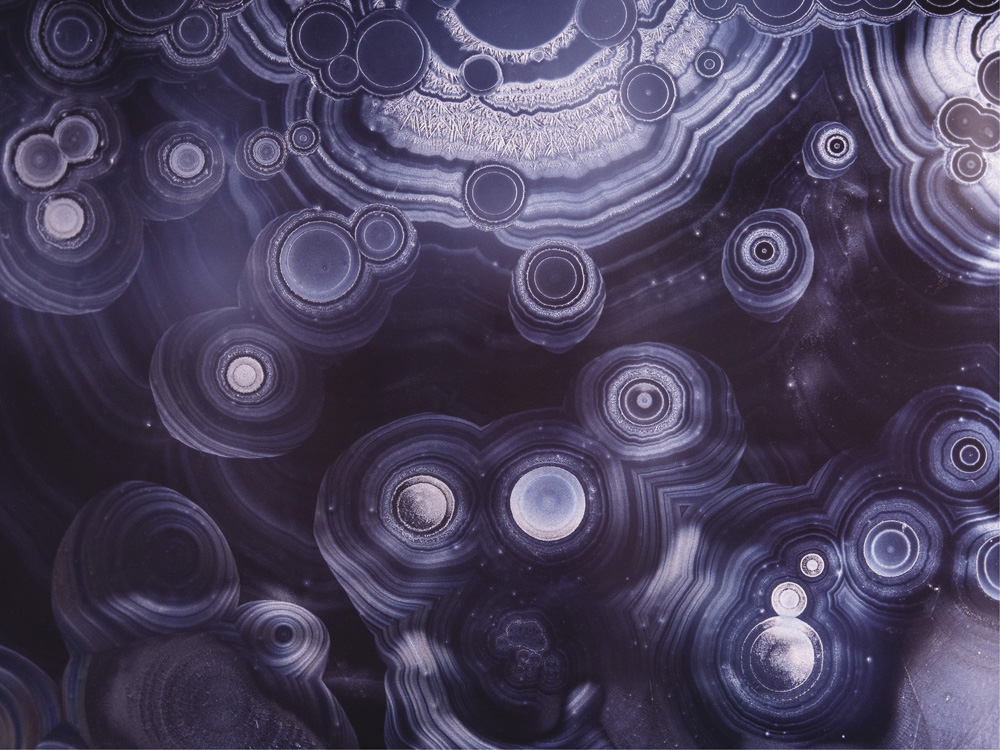

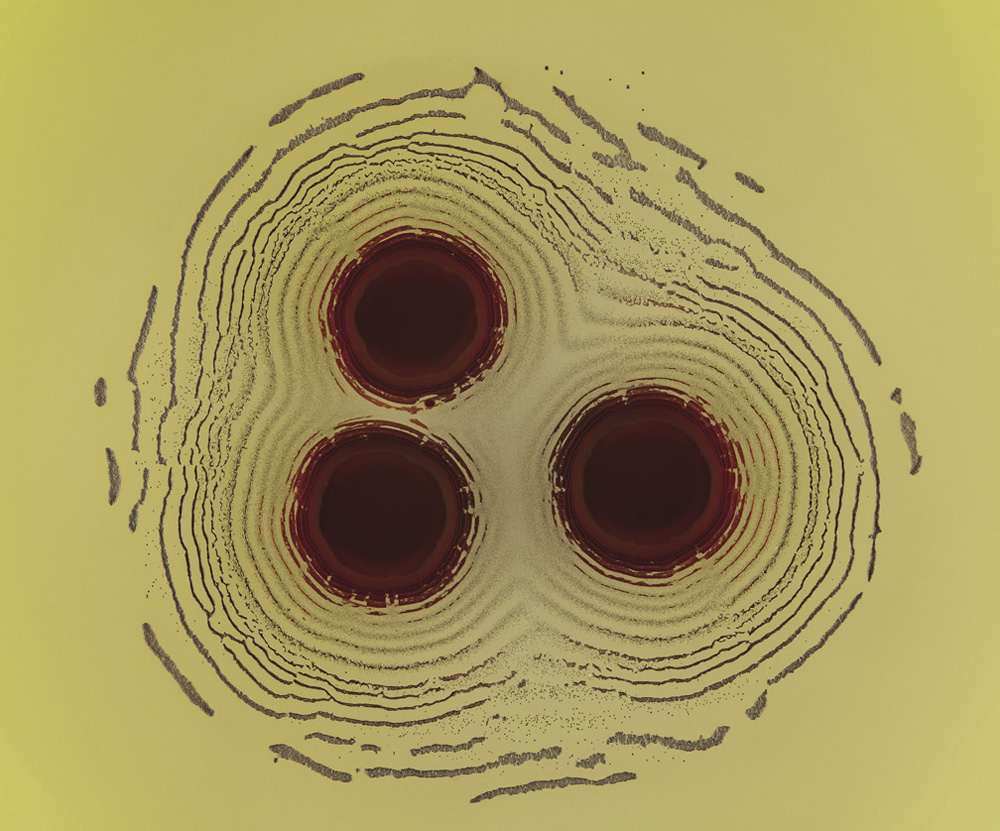

Patterns formed after a thin layer of sodium silicate solution dried on the wall of a glass beaker: the exact mechanism of pattern formation here is not known, but it probably involves the kind of reaction-diffusion process discussed in this chapter

Patterns formed after a thin layer of sodium silicate solution dried on the wall of a glass beaker

Thomas Pynchon's monumental masterpiece Gravity's Rainbow (1973) must be among the most chemically literate works of fiction ever written. It's no surprise that Pynchon, an engineering graduate from Cornell, would know a thing or two about science, but the crazed chemical invention that laces his account of Nazi rocket science in the Second World War is almost chillingly plausible, not least in its evocation of the kind of experiments the Germans conducted in polymer chemistry that ended up saving Primo Levi's life in the concentration camp.

Almost in passing, the reader encounters this curious little passage:

If the Jewish wolf Pflaumbaum had not set the torch to his own paint factory by the canal, Franz might have labored out their days dedicated to the Jew's impossible scheme of developing patterned paint, dissolving crystal after patient crystal, controlling the temperatures with obsessive care so that on cooling the amorphous swirl might, this time might, suddenly shift, lock into stripes, polka-dots, plaid, stars of David.

Making patterned paint that forms itself into spots and stripes sounds like the quest of a lunatic. But in fact such substances exist.

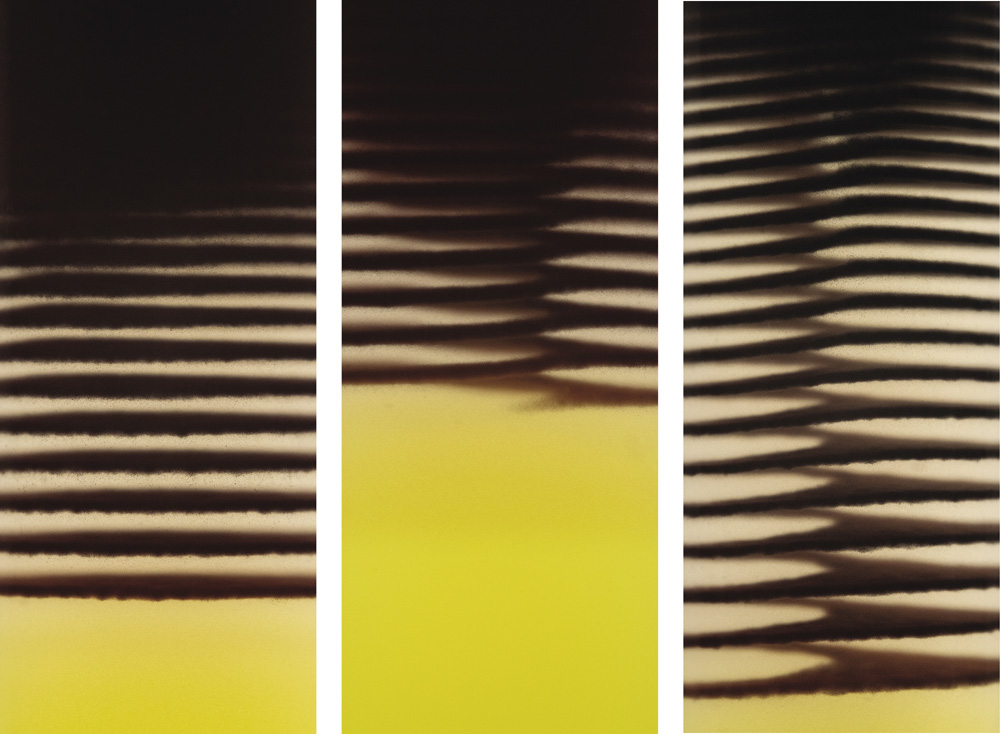

Admittedly, they are not really paints. But there are mixtures of chemical ingredients that, when spread in a shallow layer, will gradually separate into evenly spaced arrays of colored spots and stripes: yellow on a blue background, like a psychedelic animal pelt.

That isn't an idle comparison. These chemical patterns, called Turing structures and first made experimentally in the 1990s, are believed to be a kind of artificial analogue of the markings picked out in pigments on the skins of animals such as leopards and zebras. The flat, scaled bodies of the Emperor angelfish even have stripes in the same yellow-blue color scheme, and they too appear to be Turing structures.

These are among the most remarkable examples of how chemical processes can create patterns of striking beauty, some of which adorn the natural world around us.

The emergence of regular patterns of this sort seems to fly in the face of the second law of thermodynamics, which implies that all processes of change tend toward states of greater disorder (higher entropy). It's not easy to see how they could possibly be sustained in a soup of molecules all diffusing randomly, which would be expected to wash away any signs of regularity. But such chemical patterns reveal once again how the world may generate order out of chaos—how it may self-organize.

“Chemical patterns are generally possible only in nonequilibrium conditions.”

Scientists call such pattern formation “symmetry breaking.” That might sound odd, because we usually associate regular patterns with symmetry—it feels as though their appearance should instead be a case of symmetry making. Yet the state of highest symmetry is complete uniformity: everything looks the same in every direction. We don't tend to think of that bland situation as symmetrical. But once you acknowledge that the characteristic of a symmetrical object is that it looks unchanged if we transform it by, say, rotating it or reflecting it in a mirror, you'll appreciate how uniformity indeed possesses the highest symmetry, since any transformation like that then has no apparent effect. If an “amorphous swirl” of chemicals, the same everywhere, suddenly “locks” into a pattern such as a row of stripes or a lattice of spots (or for that matter, a field of stars of David), its symmetry has been lowered—which is to say, in some degree “broken.”

An amorphous swirl of well-mixed substances is uniform but not ordered: its uniformity comes precisely from the fact that the molecules are distributed at random. The reason why self-organization in a chemical system like this doesn't really defy the second law of thermodynamics is that the system has not yet reached its equilibrium state: it is out of equilibrium, where the rules of thermodynamics lack the authority to prescribe its behavior. Chemical patterns like Turing structures are generally possible only in these nonequilibrium conditions, which might for example mean that we must sustain them by constantly feeding them with fresh reagents. Left for a long time without any disturbance, the pattern will dissipate as a state of equilibrium is reached.

Spontaneous ordering and patterning of chemi-cal systems has been known for over a century. In 1910 the Austrian-American ecologist Alfred Lotka explained how a brew of reacting chemicals might, under the right conditions, produce oscillations in the concentrations of the ingredients. Lotka wrote down mathematical equations describing hypothetical chemical reactions, and showed that the solutions to the equations could be oscillatory: one compound, for example, might grow in concentration over time, then decline, then grow again. Lotka found that these oscillations would gradually die out, but in later work he showed how they might continue indefinitely if the mixture was kept away from equilibrium.

This was all theory—and Lotka was not terribly interested in oscillating chemical reactions anyway. He regarded the interactions of these chemicals as analogous to the way animal predators consume their prey in ecosystems. Lotka argued that in such a scenario animal populations may undergo periodic fluctuations too (and they do). All the same, Lotka suggested in a paper of 1920 that “in chemical reactions rhythmic effects have been observed experimentally.” He didn't explain what led him to make that claim, but just a year later a chemist at the University of California at Berkeley reported a reaction of precisely that sort. Even though he offered Lotka's scheme by way of explanation, no one took much notice. It seemed too peculiar.

It wasn't until the 1950s and 1960s that chemists began to take seriously the idea that chemical reactions, rather than progressing smoothly from reactants to products, could exhibit genuine oscillations. A Russian biochemist named Boris Belousov saw such a to-and-fro in a mixture that he concocted as an artificial analogue of the enzymatic breakdown of glucose in cell metabolism. But because his findings were then thought to violate the principles of thermodynamics, Belousov wasn't believed; the general view was that he must have screwed up the experiments.

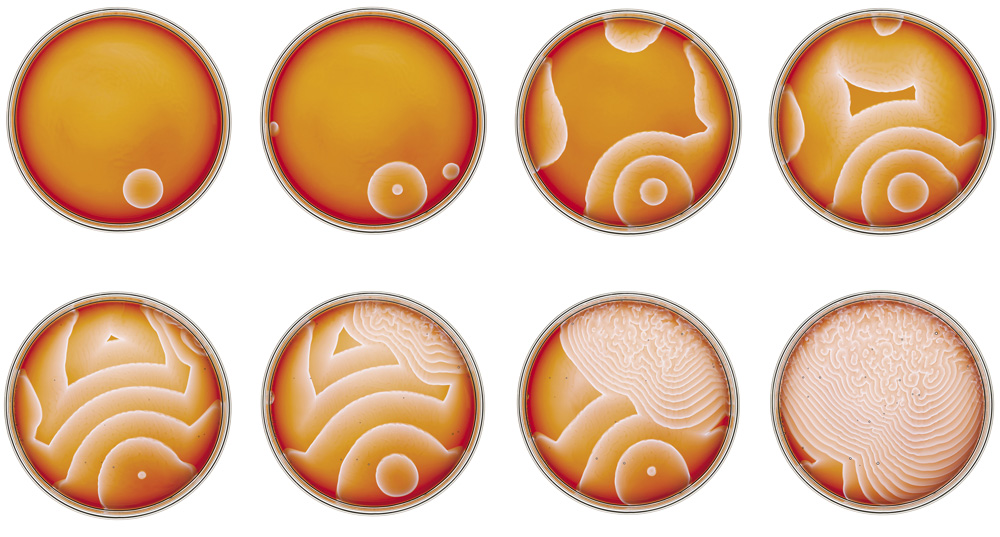

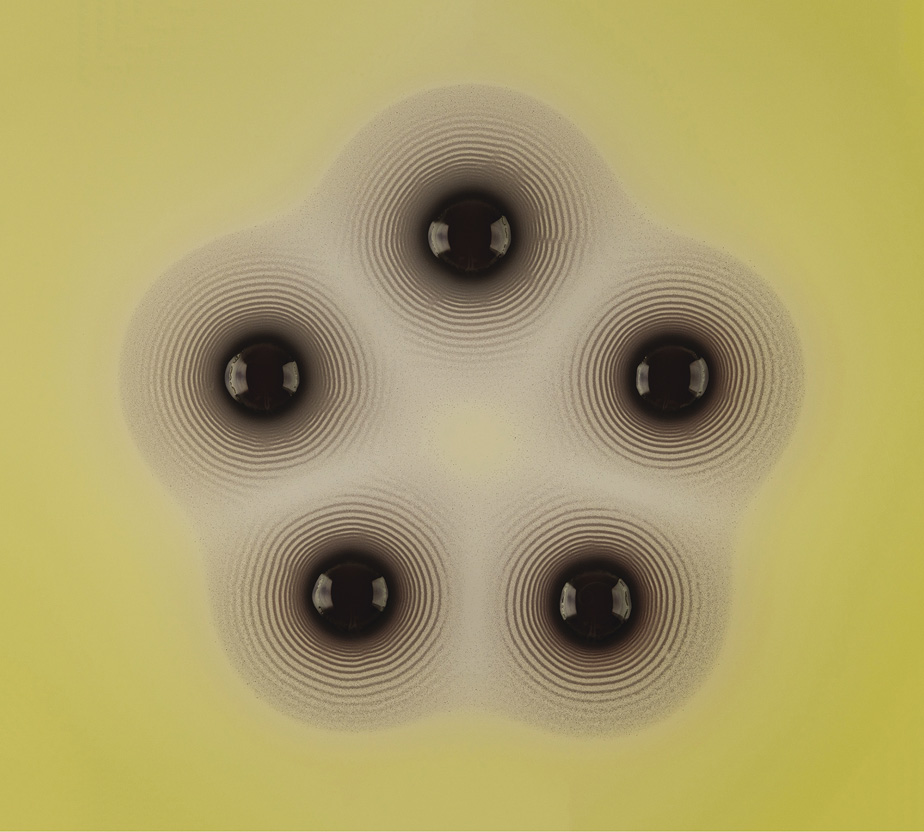

Target and spiral patterns in the BZ reaction. Notice that the wavelength of the spirals is smaller than that of the targets.

“The dish fills with a constantly changing pattern of concentric circles, growing and annihilating.”

This attitude slowly changed when, a decade later, another Russian chemist named Anatoly Zhabotinsky in Moscow found a different set of reagents that produced oscillations switching between red and blue—back and forth, again and again at regular intervals. It could no longer be denied that chemical oscillations are real: they were obvious to anyone who watched this reaction, now known as the Belousov-Zhabotinsky (BZ) reaction.

That's striking enough in itself. But even more startling is what happens if you let the BZ reaction run without the stirring that will keep the mixture uniform at each instant. In that case, the color change doesn't happen throughout the solution all at once. It begins in one place and spreads in waves.

Say you have filled a Petri dish with a thin layer of the mixture, which begins in the red state. Here now appears a spot of blue—and, rather like a spot of mold, it expands. But at a certain point a red patch opens up in the center of the blue, so that there is now a ring of blue, growing ever broader like a ripple in a pond. Then a new blue spot appears in the center of the red patch—and soon we have two concentric blue rings. Another follows, and another, at regular intervals: a series of chemical waves, creating a concentric target-like pattern.

But it's not alone; the same has happened elsewhere in the fluid layer. Eventually two of these blue ripples meet—whereupon they vanish at the point of overlap, as though they have canceled one another. The dish fills with a constantly changing pattern of concentric circles, growing and annihilating. Sometimes these waves might take not a target-shaped form but spirals, rotating out from their central core.

The oscillations of the BZ reaction are caused by a phenomenon called autocatalysis, in which one of the products of the reaction (let's call it A) acts as a catalyst that speeds up the rate of its own production. This is a positive feedback: the more A there is, the faster it appears. But that can't go on forever: eventually this burst of reaction exhausts all the ingredients, and the production of A ceases. This allows the reaction to flip into another state that produces a different product—call it B—which happens to replenish the ingredients needed to make A. When there is a sufficiency, the formation of A can resume and a new cycle starts. Now suppose that some chemical on the “A branch” is colored blue, and one on the B branch is red, and we have a recipe for the BZ reaction's oscillating color scheme.

Those targets and spirals need a further ingredient: space. An autocatalytic process may run out of steam in one place while still proceeding in another, simply because the necessary ingredients have been used up in the former vicinity and have not yet been replenished by fresh reagents diffusing in from elsewhere. In other words, switching between the two branches (A and B) is now governed by a balance between the rate at which substances are consumed by reaction and are refreshed by diffusion. Systems whose behavior is controlled by such a balance are called reaction-diffusion systems, and they are common sources of pattern in nature.

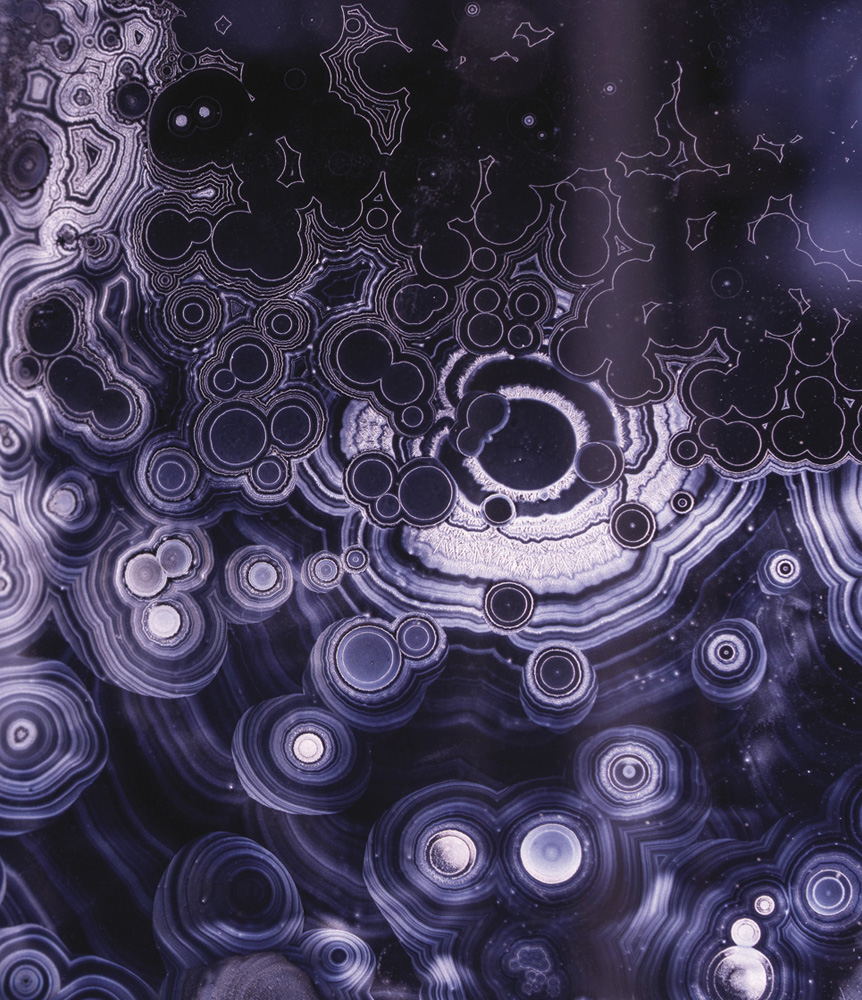

The banded patterns in minerals such as agate and onyx are thought to originate this way; the BZ target patterns might already have put you in mind of them. The bands are typically different types of mineral, and the idea is that they precipitate out of the hot, salt-rich fluids within the Earth in waves, where now the crystallization of a mineral plays a role similar to the autocatalytic reaction of the BZ mixture.

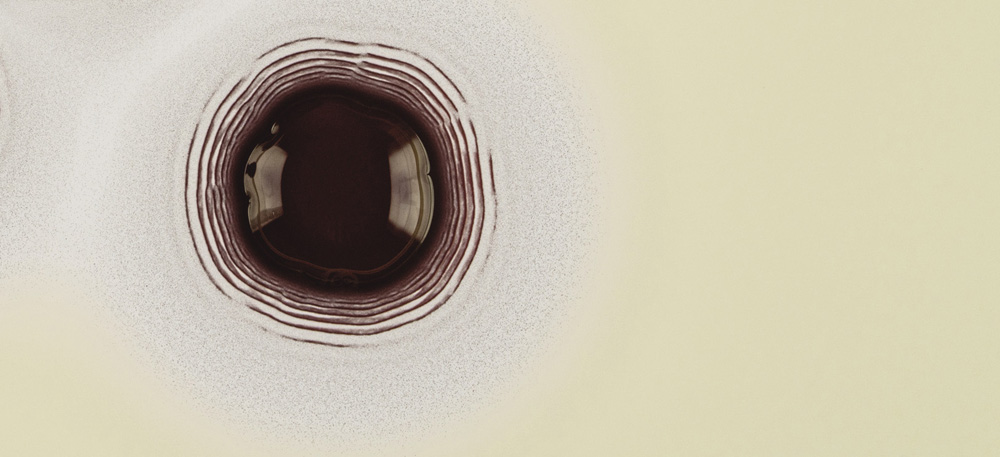

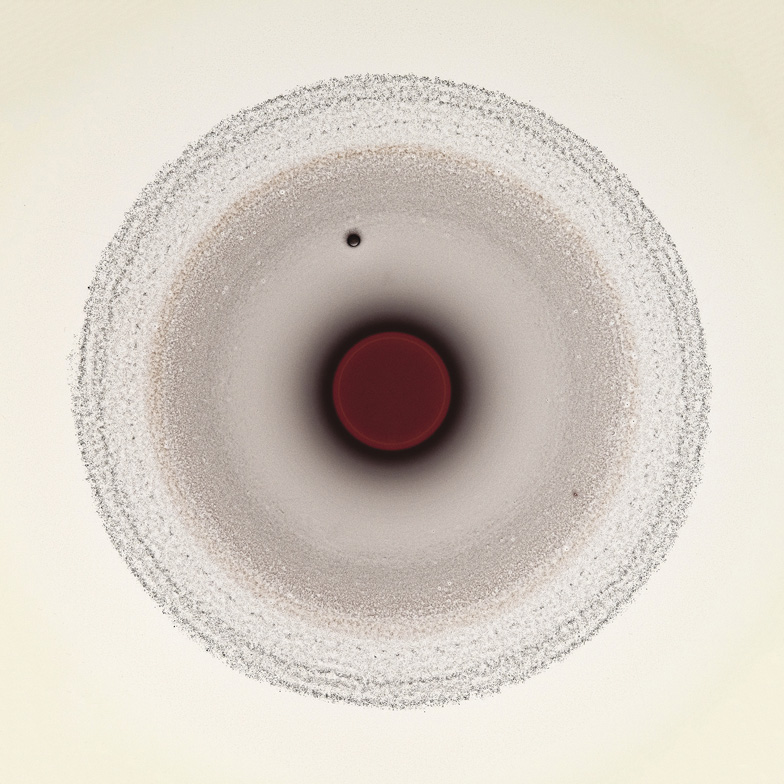

Such processes tend to happen very slowly in nature, but can be mimicked in the chemical lab. This was known even before Lotka had described his oscillating chemical reactions. In 1896 a German chemist named Raphael Eduard Liesegang was experimenting with reactions of silver nitrate in gelatin, these being the key ingredients of the emulsions then used in photography—a technology in which Liesegang was deeply interested. He found that he could create concentric rings of an insoluble, dark silver salt when he let drops of silver nitrate diffuse through a layer of gel containing potassium chromate, with which silver reacts. If the reaction was carried out in a vertical glass tube filled with the gel, the silver nitrate being added at the top of the column, then the rings became a series of horizontal bands appearing one after another down the tube.

Some scientists at that time were struck by how these Liesegang bands resembled the stripelike markings on animals—squint at the column with its pattern of light and dark stripes and you could imagine you're seeing a zebra's leg or a tiger's tail. Others derided this as too far-fetched.

Liesegang bands, formed by the reaction of silver nitrate with potassium chromate within a gelatin gel; the bands, caused by precipitation of silver chromate, form as the silver nitrate diffuses through the gel column from the top (in the images on the facing page, the bands are helical)

The bands of agate are thought to be formed in a Lieseganglike process by the periodic precipitation of different forms of silica as the crystals grow from a hot solution of silicate

Rings and bands formed by sodium silicate solution drying on a glass surface

Liesegang rings formed as a central droplet of silver nitrate diffuses into a layer of gel containing potassium dichromate in a Petri dish

“This dappled pattern was strikingly reminiscent of the random dark blotches on the hide of a cow or a dalmatian dog.”

But it wasn't really—for Turing patterns, now strongly suspected of being evident in animal markings, are a kind of reaction-diffusion pattern too. Unlike the chemical waves of the BZ reaction, however, these spots and stripes don't move; they are stationary patterns.

They are named for the man who first predicted them in 1952: the British mathematician Alan Turing, better known as a pioneer of the digital computer and as the codebreaker who worked to crack the German Enigma code at Bletchley Park in England during the Second World War.

Turing's interest in patterns and self-organization was sparked by another symmetry-breaking process: the emergence of a “body plan” from an embryo, which seems to start out as a perfectly spherical (and thus symmetrical) object. How can one part of this blob of cells “decide” to be the head, another the torso, and with progressive elaboration grow fingers, toes, organs?

Turing didn't know what Belousov was up to at that same time in the Soviet Union, but he hit on the same ideas that eventually explained the Russian biochemist's observations. In fact, it was in Turing's seminal paper on pattern formation that the terminology of reaction-diffusion processes was coined.

Turing supposed that embryonic development might be governed by biological molecules that he called morphogens (“shape-formers”), which diffuse through the cells and somehow activate genes that control development. The question is how the embryo ends up with genes switched on in one part but not in another.

Turing presented a theory showing how a combination of reaction and diffusion of morphogens could explain this. Again the mechanism depends on feedbacks on the (morphogen) reaction rates caused by catalysis, and on the rates of diffusion. It wasn't obvious at first what the key characteristics of his equations were, but later researchers showed that there were two main ingredients in the process. One morphogen behaves as an activator, autocatalytically producing more of itself. Another acts as an inhibitor that disrupts this runaway amplification of the activator. If the inhibitor diffuses faster than the activator, the result is that local “islands” of activator can appear in a sea of inhibitor: the mixture becomes patchy. Turing presented a sketch of what this “dappled” pattern might look like: strikingly reminiscent of the random dark blotches on the hide of a cow or a dalmatian dog.

Once computers were available to perform the calculations that Turing had to do by hand, it became clear that in fact his scheme generates islands that are more or less evenly spaced, and which can take the generic forms of either spots or stripes. There's a lot of regularity to these patterns: the stripes lie parallel and the spots may be arranged in the triangular formation of packed spheres. But these arrays are often filled with “defects”: stripes may bend and merge, the spots break ranks. If anything, this injection of a little disorder only increases the resemblance to animal marking patterns.

Researchers have now devised Turing-type theoretical schemes that can produce patterns very much like those on a wide range of animals: the rosette-type spots of jaguars, the crazy-paving networks of giraffe pelts, the merging and fragmentation of spot and stripe-type formations on tropical fish such as the whale shark. On emperor angelfish, a Turing-type patterning process can account for how yellow stripes can seem to “unzip” into pairs as the creature grows.

All this makes it seem highly likely that such animal markings are indeed produced by Turing-type chemical patterns. The idea is that the patterns in skin or hair pigmentation are laid down at the embryonic stage, when morphogen molecules in the body switch pigment-producing genes on or off, and then this fixed pattern simply grows bigger with the animal. However, no one has yet managed to find a molecule that might act as such a morphogen, so the case is not yet definitely proven.

Still, it's now widely accepted that Turing's process produces other types of pattern in living organisms. The quasi-regular, evenly spaced hair follicles of mammals seem to be positioned this way, as are the parallel ridges of a dog's palate. Here, morphogens turn on not pigment genes, but rather genes involved in generating some body or tissue structure.

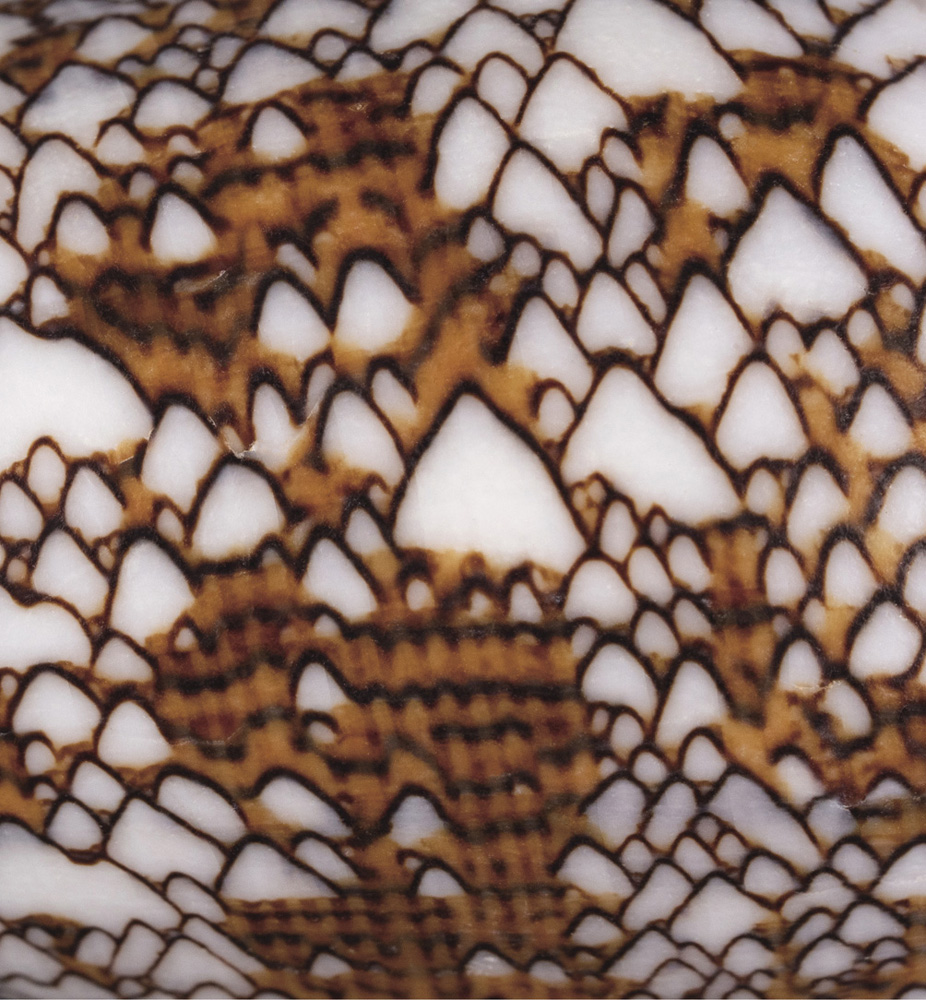

Traveling chemical waves and stationary Turing patterns are likely also to paint the ornate markings seen on seashells, where light and dark areas are created along the growing rim of the shell. As the shell grows, these regions become drawn out into a frozen record of patterns past: stationary patches on the rim become stripes, while moving patches turn into V-shaped chevrons. Reaction-diffusion processes involving morphogens that control coloration are also believed to give rise to the spectacular patterns on butterfly wings. Evolution takes these pattern-forming schemes and tweaks them for adaptive purposes, fashioning them into camouflage or allowing one species to mimic another to ward off predators with a pretense of being poisonous. There is after all no conflict between the operation of spontaneous pattern-forming processes in nature and the imperatives of Darwinian natural selection. Far from it; chemical reaction-diffusion schemes might supply the basic palette with which evolution can paint a thousand useful wonders.

Liesegang rings formed as a central droplet of silver nitrate diffuses into a layer of gel containing potassium dichromate in a Petri dish

“Chemical reaction-diffusion schemes might supply the basic palette with which evolution can paint a thousand useful wonders.”

The end result of a Liesegang process involving a drop of silver nitrate diffusing into a gel laden with potassium chromate

Liesegang rings formed from the reaction of lead nitrate diffusing from the central droplet into a gel perfused with potassium iodide

Pigment patterns on a shell of the venomous sea snail Conus textile

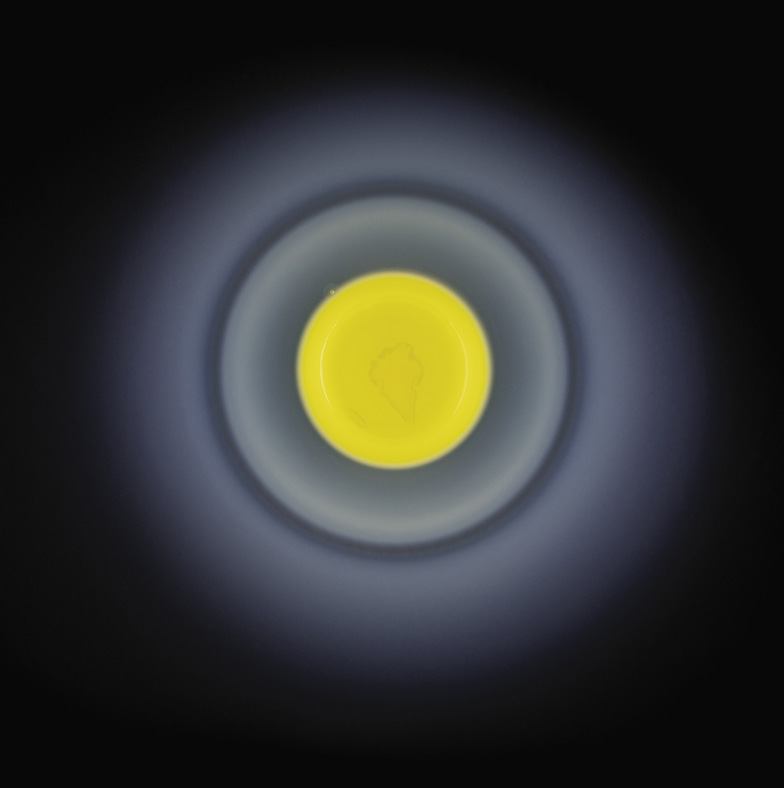

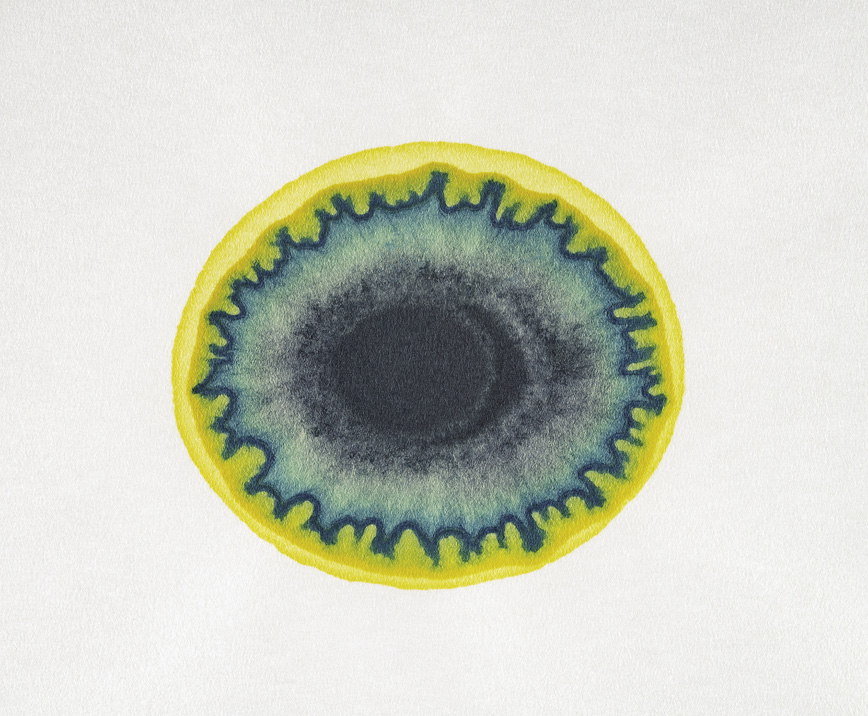

A pattern made in the process identified by Runge: two droplets of iron trichloride are added to blotting paper and allowed to dry, then two droplets of potassium ferrocyanide are added on top, producing the blue iron ferrocyanide

Chemists have been fascinated by patterns for pretty much as long as their discipline has formally existed. The laws governing “morphology”—the formation of shape—obsessed the early nineteenth-century German polymath Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who sought them in particular in botany. Goethe's rather mystical ideas infuse the book published in 1855 by his friend, the chemist Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge, the German title of which might be loosely translated as The Drive to Formation of Matter. Runge presented stunning images created by chemicals placed on blotting paper: patterns that he considered to show the chemical elements somehow determining their own forms and destinies.

Runge was a leading chemist of his day, an expert on organic “natural products” extracted from poisonous plants such as belladonna, and also on the chemistry of color. He investigated the black tarry substance called coal tar, a residue of coal gas production, from which were obtained the organic chemicals used to make so-called coal tar dyes which launched the modern chemicals industry.

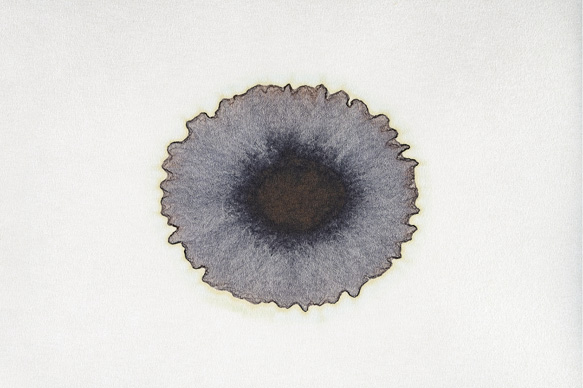

Another of Runge's chemical patterns, made by adding potassium ferrocyanide onto dried droplets of copper sulfate

In the course of his studies, Runge found (probably by chance) that solutions of colored salts dropped onto one another on blotting paper would spread to produce complicated, kaleidoscopic blots. Some looked like lichen on rock, others like eyes, flowers, banded agates. “Here was shown,” he wrote, “at once a new world of formations, shapes and mixtures of color which I had, of course, never thought of before, never even suspected, and therefore whose actuality surprises all the more.”

In Runge's patterns, reaction and diffusion are again doing their work, this time under the influence of the fibers of the paper along which the chemical solutions wick by capillary action. He presented some of these images, pasted in by hand, in his 1850 book On Color Chemistry, where he hoped they might inspire painters, decorators, and textile printers. It was in the sequel, The Drive to Formation of Matter, five years later that Runge alluded to Goethe's ideas about the “formation” or shaping influence—what the Germans call Bildung—that he considered to be a fundamental driving force of nature. An agency like this, Runge wrote, “inhabits the elements from the very beginning,” and he suspected it was the root of the “life force that is active in plants and animals.”

A “Runge figure” made by depositing droplets of lead nitrate onto a dried droplet of potassium dichromate

A Runge figure made from copper sulfate, iron sulfate, and potassium ferrocyanide

A Runge figure made by adding silver nitrate onto dried droplets of potassium chromate

A Runge figure made by adding potassium chromate onto dried droplets of silver nitrate

“For Runge it was almost as though the elements were itching to organize themselves into living matter.”

A Runge figure made from manganese sulfate and potassium chromate

For Runge this gave chemistry an inherent creativity of its own, beyond anything the chemist might impose. It was almost as though the elements were itching to organize themselves into living matter.

We might use different words today, but the appearance of reaction-diffusion patterns does lend some support to the view that nature has a sort of spontaneous impulse for creativity and variety waiting to emerge when the conditions are favorable. We can explain most if not all of what goes on in these chemical patterns using hard-nosed math and well-established rules of physics and chemistry. And yet this sober analysis won't extinguish the awe we feel as we watch a spiral wave unscroll or a chemical mixture resolve itself into a field of leopard spots. When nature reveals what it can do, we're right to be entranced.

Patterns formed from sodium silicate drying on a glass surface

Further reading

- Ball, P. Patterns in Nature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016.

- Ball, P. The Self-Made Tapestry: Pattern Formation in Nature. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Leslie, E. Synthetic Worlds: Nature, Art and the Chemical Industry. London: Reaktion, 2005.

- Meinhardt, H. The Algorithmic Beauty of Sea Shells. Berlin: Springer, 1995.

- Murray, J. D. “How the leopard gets its spots.” Scientific American 258, 62 (1988).

- Turing, A. M. “The chemical basis of morphogenesis.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 237, 37–72 (1952).

- Winfree, A. T. When Time Breaks Down. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987.