Tyranny over the mind is the most complete and most brutal type of tyranny.

—Milovan Djilas

We should rid our ranks of all impotent thinking. All views that overestimate the strength of the enemy and underestimate the strength of the people are wrong.

—Mao Zedong*

After almost a quarter of a century of distant rivalry followed by a successful, if prickly, four-year partnership during World War II, the West and the Soviet Union came face to face in 1945 and over the next seven years developed into resolute enemies. This antagonism was accentuated by the presence of nuclear weapons, forceful ideological competition, and an unparalleled mobilization of civilians imbued with the fear of an imminent World War III. By 1949, the Big Three’s wartime practices of direct consultation and compromise had ceased, and for the next three years the United States and the USSR became locked in a Cold War.

The rupture did not occur at once. Indeed, there has been an ongoing—and ultimately unresolvable—debate among historians over when the Grand Alliance dissolved, when the Cold War began, and who was responsible. This origins debate, heated for a half century by partisan positions, has now been tempered by the collapse of the Soviet Union and the opening of its archives and also by the passage of time and the challenge of new global problems, all of which may obscure the Great Powers’ actual situation, decisions, and interactions after 1945.

The rupture in the Grand Alliance occurred in the wake of the immense human and material devastation in World War II. Some sixty million people had died, and the combatants’ bombs had left a swath of destruction from London to Tokyo. Moreover, the losses were uneven. While large parts of Europe and Asia faced enormous human and physical losses along with a flood of wounded soldiers, hungry and diseased civilians, and fleeing refugees, the United States emerged from the war with no physical damage to its mainland, a death toll (400,000) that was only a fraction of the USSR’s loss of 30 million people, and a booming economy with a $211 billion gross national product.

There was also no “zero hour” in 1945. The total defeat of the Axis powers had given the victors not only a heady sense of power but also a new realization of their vulnerability. The Soviet and US responses of “Never again!” to the attacks on June 22 and December 7 necessitated an active defense of their national interests, clothed in the garb of “security.” Each expected its partners to comply with its expansive desires for maintaining this security, and each was irate at every demonstration of the other’s bad faith and aggressiveness, sentiments augmented by both sides’ vigorous intelligence gathering and their less frequent personal encounters.

Consequently, along with the immense tasks of postwar reconstruction came the perhaps inevitable clash of interests among the Grand Alliance. Inevitable too was the expansion of the victors’ rivalry. Although Europe was the source and the core of the Cold War, the rest of the world was inevitably drawn in. Because the struggle with the Axis had been a global one and Europe’s empires had been disrupted, Asia and the Middle East, and later Africa and South America, would all be engulfed by the US-Soviet struggle.

Leading personalities still counted, but in a different way than in wartime. President Truman and Prime Minister Atlee headed vast political, diplomatic, and military establishments weighed down by global burdens over which they could never exert complete control. In choosing their diplomatic paths the novice US and British chiefs navigated among rival advisers, bureaucracies, legislators, and publicists at home and beleaguered and tough foreign governments abroad. Even Stalin, who formulated Soviet foreign policy almost singlehandedly, received conflicting advice from his colleagues and often faced intractable client states outside his borders.

The Great Power rivalry that followed World War II was fueled by a resurgence of ideological competition between communism and capitalism, which had been restrained in wartime. The East-West clash also became systemic, rooted in almost every institution—economic, military, political, diplomatic, religious, and even cultural. For a world newly freed from war, the prospects were menacing. Contemplating the dire prospect of “two or three monstrous super-states, each possessed of a weapon by which millions of people can be wiped out in a few seconds, dividing the world between them,” George Orwell in October 1945 used the term “Cold War” to describe “a peace that is no peace” and grimly predicted that pressures would develop within both sides to ensure conformity and stifle dissent.* The first seven postwar years thus had the semblance of a global compression chamber, but one that was also porous and short-lived—and unavoidably so.

NUREMBERG: THE FINAL COLLABORATION

Shortly after the Potsdam meeting, on August 8, 1945, British, French, Soviet, and US jurists adopted a detailed charter governing the international military tribunal that would conduct the trial of the major German war criminals. This momentous undertaking—first agreed upon in Moscow in 1943 and confirmed at Tehran, Yalta, and Potsdam but requiring six weeks of laborious negotiations in the summer of 1945—opened on November 21 in Nuremberg, the site of spectacular annual Nazi rallies and where their notorious 1935 racial laws were adopted. Before its ending on October 1, 1946, the four-nation tribunal heard hundreds of witnesses, scrutinized thousands of pages of captured Reich documents, meted out sentences to twenty-four individuals and seven organizations, and produced an unprecedented and voluminous historical record of aggressive war, state violence against combatants and civilians, and crimes against humanity.

The Cold War dimension of the trials is surprisingly unexplored. One of the final acts of the Grand Alliance, the Nuremberg trials were immediately controversial: defended for giving voice to the Nazis’ victims and replacing vengeance with justice, but also criticized for their faulty legal practices and politically motivated judgments toward particular defendants. The preparations for the trials by the four nations had been largely harmonious, but by early 1946 the growing East-West tension entered the courtroom. Much to the Soviets’ chagrin, the defense attorneys raised the sensitive issues of the Nazi-Soviet pact and the Katyn massacre. In contrast, the United States, Britain, and France were able to block any discussion of the Allied bombing of German cities and the atomic attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and they prevailed in the meting out of lenient sentences to German bankers and industrialists as well as to submarine captains.*

Nonetheless, the Nuremberg collaboration among the three Western governments and the USSR survived quietly for four decades, enacted through the formalities of four-power control over the Spandau prison in Berlin, where seven Nazi prisoners were incarcerated, and ending only with the death of the last inmate, Rudolf Hess, in 1987. The international tribunal was dissolved in 1946, followed by separate trials in Europe and by the US-dominated proceedings against Japanese war criminals, all raising more accusations of legal lapses and political expediency. As the Grand Alliance unraveled and the Cold War expanded, the principles and practice of international jurisdiction over war crimes and crimes of aggression disappeared from the world for almost a half century.†

On the eve of the Nuremberg trials, the first foreign ministers’ conference in London had ended abruptly on October 2, 1945, demonstrating the widening gap among the victors. Not only had they failed to reach agreement over the future of Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, but they had also clashed over the control of atomic weapons. Secretary of State Byrnes, although annoyed by Foreign Minister Molotov’s audacity, was also fearful of a permanent rupture and thus persuaded Stalin to convene another foreign ministers’ meeting. In a reprise of Tehran and Yalta, Byrnes arrived in Moscow in December 1945 brimming with confidence that US power would enable him to break the stalemate with the USSR, and he held two long meetings with Stalin. Ignoring British grumbling, US and Soviet diplomats seemed poised to work together.

The result was a series of US-Soviet arrangements bolstering their respective interests and crafting compromises to bridge their differences. In return for the West’s tacit acknowledgment of the communist-dominated governments in Romania and Bulgaria and the Soviets’ occupation and looting of Manchuria (as well as the transfer of Japanese arms to the Chinese communists), Stalin grudgingly recognized America’s leading role in Japan and the temporary presence of its troops and bases in the rest of China. The agreement on Korea—far more strategically vital to the USSR than to the United States (which was nonetheless fearful of a communist takeover, à la Poland)—was a masterpiece of Great Power improvisation. Ignoring strong local sentiments for the country’s unity and independence, the diplomats superimposed an ultimately unworkable four-power trusteeship on the Soviet-US military partition at the thirty-eighth parallel, paving the way for Korea’s eventual division.

Disagreements were quietly papered over in Moscow. Although Great Britain, the USSR, and the United States had agreed to create a UN Commission on Atomic Energy, they differed fundamentally over information sharing, surveillance, and existing stocks of atomic weapons.* There was also no resolution of their conflicting policies on Turkey and Iran. Shortly after the Moscow meeting, on the last day of 1945, the Soviet Union firmly detached itself from the postwar US-led international economic system by announcing its withdrawal from the Bretton Woods agreements, which were signed in Washington by twenty-seven governments on December 27, 1945.

Whereas the international press greeted the Moscow accords as a new and positive step toward world peace, the reality was grimmer. In stark contrast to the aftermath of World War I, by January 1946—five months after an even more ruinous war and the total defeat of their enemies—the victors had neither convened a peace conference nor produced separate peace treaties with Germany and its five European allies.† In Germany the occupying powers were pursuing competing strategies. While proclaiming their conciliatory intentions, their leaders began recoiling from a thorny and increasingly unpopular relationship.

Britain and the United States blamed the Soviet Union for the unsettled world. Taking the lead was Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin, the novice but tough diplomat and former member of Churchill’s wartime cabinet who espoused Labour’s traditional antipathy toward Moscow. Truman, increasingly irritated by US inability to alter Soviet positions, immediately scolded the returning Byrnes for appeasing Stalin. The US press began to fan anti-Sovietism with reports of the USSR’s suppression of the anticommunist opposition in Eastern Europe, Soviet vetoes in the new United Nations, and the sensational discovery of a communist spy network in North America.*

The first postwar elections for the Supreme Soviet provided a platform for Stalin’s reply. In his much noted, often misinterpreted speech to the communist faithful on February 9, 1946, the Soviet dictator sent a mixed message, praising the wartime achievements of the Grand Alliance but also underscoring capitalism’s bellicose tendencies, announcing the expansion of Soviet civilian production and warning of the rapid buildup of its industrial and military power to protect the Motherland “against all contingencies.” Party hard-liners G. M. Malenkov and L. M. Kaganovich went further, proposing that the Soviet Union go its own way in world affairs.

The West escalated the rhetoric. In Fulton, Missouri, on March 5, 1946, with Truman at his side, Churchill warned that an “Iron Curtain” had descended across the center of Europe. Although rejecting the idea that war was either imminent or inevitable and advocating continued dialogue with Moscow, Britain’s opposition leader insisted on the indispensability of Anglo-American unity and an increase of the West’s armed might. Stalin’s retort, an unprecedented, scripted interview published in the official Soviet newspaper Pravda, characterized his old partner as a “racist” and “warmonger,” in a sly reference to Hitler.

Behind the scenes, disgruntled diplomats also weighed in. From Moscow in February and March 1946 came detailed dissections of the Soviets’ nationalist and Marxist mind-set and their aggressive behavior toward their neighbors by the US and British envoys George Kennan and Frank Roberts, who also revived prewar historical and racial stereotypes about Russia itself. Six months later the Soviet ambassador in Washington, Nikolai Novikov, delivered his critique of US “striving for world supremacy” as witnessed by its thirst to control the world’s economic resources and its atomic saber rattling against the Soviet Union. All three diplomats came to the identical conclusion: the prospects for further collaboration with an aggressive power were dismal.

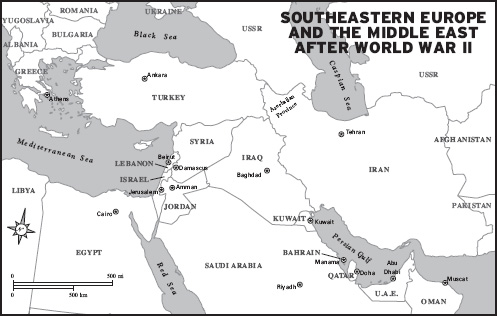

Map 3. Iran, Greece, and Turkey became sites of US-Soviet confrontation between 1946 and 1948.

There were also dissenting voices to the emerging US-Soviet confrontation. In September 1946 the US secretary of commerce and former vice president Henry Wallace advocated peaceful cooperation with the USSR but also urged Stalin to maintain an open door to US trade with Eastern Europe. Thereupon some Americans criticized Wallace for his naïve idealism, while others took him to task for upholding US economic imperialism.

It is thus not surprising that 1946 witnessed the first direct clashes between the West and the Soviet Union. The area of contestation was Iran, and at issue was the Soviet refusal to withdraw troops from its northern zone by the March 2, 1946, deadline.* Stalin had decided to exploit separatist movements in Iran to force oil concessions from the Tehran government. Observers also suspected another motive: to hinder US and British oil companies from prospecting in the north. At the last minute Stalin summoned the Iranian prime minister to Moscow and, with the threat of Soviet troop movements toward Tehran, demanded an oil concession.

Once the deadline had passed without a Soviet withdrawal, the United States and Britain went into high diplomatic gear in defense of the sanctity of international treaties and their oil interests. After instigating an Iranian appeal to the United Nations, Byrnes publicly condemned Moscow’s “imperialism” before the Security Council, causing a dramatic walkout by Andrei Gromyko, the Soviet Union’s permanent UN representative. The old diplomatic niceties among the three had ended. Stalin, surprised by the furor and fearing US retaliation elsewhere, backed off. Prudently, he removed his troops on May 9 but secured the oil concession (which the Iranian parliament refused to ratify). He also withheld support from his Iranian clients, who were crushed by the government later that year.

The Iranian episode was the first chilling lesson in Cold War brinkmanship. Instead of a bargain struck by the three foreign ministers, a seemingly minor episode at the periphery (complicated, to be sure, by oil and ethnic tensions) had developed into a full-blown international crisis with distinct winners and losers. Later that year, a US show of naval force along with intelligence reports of US combat scenarios convinced Stalin to withdraw his demands on Turkey to establish Soviet naval bases along the Straits. But while some Westerners exulted in their easy victories, these confrontations also had consequences: not only bolstering hard-liners on both sides but also diminishing Stalin’s confidence in an equal treatment by his partners and reinforcing his obsession with building an atomic bomb.

The German question remained the center of dispute. Unlike the single-power control that had been established in Japan and the Balkans or the dual control over Korea, in Germany four states had inherited the awkward Potsdam arrangement of joint governance of Germany through a polarized Allied Control Council combined with almost total political, economic, and judicial control over their respective zones. In addition, the occupying powers faced the day-to-day complications of ruling a hungry and sullen conquered people.

Stalin, looking back to the post–World War I period, had hoped for another rapid US withdrawal from Europe and the reestablishment of a unified and neutral but also smaller Germany from which he would extract substantial reparations. Siding with Kremlin pragmatists, he restrained the ideological fervor of the German communists, ended wholesale looting and food requisitions, and launched a “charm offensive” in 1946, calling for a “united and peaceful” Germany on the model of Austria.*

The Americans and British parried the Soviet challenge by moving further toward partition; as occupiers of Germany’s largest, richest, and most populous regions, they held the upper hand. On May 3, 1946, the United States suspended reparations deliveries to the Soviets to protect the economic well-being of its zone, and that month Britain, citing Soviet obstruction, assailed the continuation of four-power control. On September 6, 1946, Byrnes, in a major speech to German dignitaries in Stuttgart, announced two key facets of the new US policy: the amalgamation of the US and British zones (Bizonia) and an American commitment “to stay” and to restore freedom, self-government, and a robust capitalism to the German people. In another, quite clever repudiation of the Potsdam accords, Byrnes challenged the permanence of the Oder-Neisse border separating Poland from Germany, forcing Stalin to take the side of his Polish comrades against the Germans he was trying to court.

The remainder of 1946 was consumed by acrimonious negotiations over the peace treaties with Nazi Germany’s former allies, with the terms for Italy drawing the most heated discussion. Harking back to their wartime strategy, the British were intent on defending their vital interests in the Mediterranean against Soviet claims, specifically in regard to Libya and the port of Trieste.†

The United States was the crucial mediator. Earlier in the year it had tipped decisively toward London, granting a huge (and controversial) $3.75 billion loan to Britain but denying a similar Soviet request. Two civil wars were now raging, in China and in Greece, and although the Soviet hand was not evident in either of these, the United States had become increasingly committed to halting left-wing revolutionary movements. Thus, in dealing with the question of Libya, Washington blocked Moscow’s bid for a presence in North Africa; swallowing its long-standing resistance to European imperialism, it countenanced a four-year Franco-British trusteeship under UN supervision. On Trieste, the United States strongly supported the British, and a still-cautious Stalin (much to the fury of his Yugoslav ally) backed down. The United States authored a compromise solution that kept the Adriatic port out of communist hands and eight years later awarded the city to Italy.

The signing of the peace treaties with Bulgaria, Finland, Hungary, Italy, and Romania on February 10, 1947, marked the culmination of the Great Power arrangement that Roosevelt had envisaged. Truman, facing the first Republican-dominated US Congress since 1932, was assuming a less conciliatory and tougher stance toward the Soviet Union. Stalin, through his intelligence sources, studied the details of Washington’s growing estrangement and pondered America’s economic and military might, its growing string of bases throughout the world, and its emerging alignment with Great Britain. The Soviet leader remained committed to his forward strategy, bolstered by the terms of the wartime agreements but also tempered with caution and pragmatism. However, by 1947 an increasingly edgy West was preparing initiatives of its own.

That year an overburdened Britain essentially turned the mantle of its global leadership over to Washington. Faced with insurgencies throughout the empire, it announced its withdrawal from the Indian subcontinent and the referral of its Palestine mandate to the United Nations. On February 21 London informed the State Department of its intention to terminate aid to Greece and Turkey in fourteen months.

Truman, his new secretary of state, George Marshall, and undersecretary Dean Acheson were determined to fill the gap created by Britain’s departure. With great speed, the State Department prepared a $400 million package of economic and military support for the beleaguered Greek and Turkish governments. In order to rally a skeptical and parsimonious Congress, the president warned on March 12 that the world had become divided into two ways of life, “democracy and totalitarianism,” and in the so-called Truman doctrine called on the United States “to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressure.”

Although Acheson had quietly assured Congress that the administration contemplated no military corollary to the Truman doctrine, this startling and expansive commitment reverberated throughout US public life. In April 1947 the venerable financier and presidential adviser Bernard Baruch used the term “Cold War” to urge Americans to unite in the face of a dire internal as well as external threat. In July “Mr. X” (later revealed to be George Kennan), in a much-noted Foreign Affairs article, called for a policy of “long-term, patient but firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies” through the “adroit and vigilant application of counter-force at a series of constantly shifting geographical and political points, corresponding to the shifts and maneuvers of Soviet policy,” an approach that would eventually result “either in the break-up or the gradual mellowing of Soviet power.”*

On June 5, 1947, Marshall focused the Truman doctrine on the economic rehabilitation of Europe. In his famous Harvard commencement speech the secretary of state issued an invitation to every nation on the continent, including the USSR, to coordinate their recovery efforts as a condition of receiving substantial US aid. Among the goals of the Marshall Plan were not only to alleviate postwar Europe’s dire economic condition and reduce the attraction of communism but also to open the door broadly to US commerce.

Stalin decided to test Washington’s initiative. Harking back to the 1920s and to Lenin’s belief in Russia’s indispensability to the West’s economic recovery, the Soviet leader sent a large delegation to the conference in Paris to explore direct and unconditional US aid to the USSR and also to offer an alternative to Washington’s domination. To their surprise and alarm, his delegates encountered strong West European endorsement of the Marshall Plan as well as a potential threat to the Soviet Union’s East European realm. Stalin backed away, recalling Molotov on July 2 and pointedly counseling the governments of Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia also to withdraw.

The Soviets’ exit created little surprise and was, in fact, a relief to Washington. It not only removed an obstacle to rapid agreement but also shifted the blame for Europe’s growing division onto the USSR. In Western Europe the prospect of Marshall Plan aid strengthened the anticommunist political forces, which were easily able to quash their leftist opponents by the end of the year. Moscow’s departure also facilitated Washington’s major goal: the inclusion of the western zones of Germany in the Marshall Plan, providing the indispensable labor and mineral resources for Europe’s revival.

Soviet historiography has asserted that the proclamation of the Truman doctrine and the Marshall Plan laid the foundation for Stalin’s decisive break with the West in 1947. Faced with the threat of an anti-Soviet bloc, Stalin abandoned his efforts at cooperation and moved to consolidate the communist position in Eastern Europe. The new Soviet stance was announced by the creation of the Communist Information Bureau (Cominform) in September 1947 as the successor to the Comintern. In his address to the new organization, Stalin’s ideological spokesman, A. A. Zhdanov, parodied the Truman doctrine, blaming US aggressiveness for dividing the world into two distinct camps—imperialist and anti-imperialist. Whatever the exact motive or moment of his retreat from multilateralism (which the Soviet archives may someday reveal), Stalin still recognized his country’s unpreparedness for another armed conflict. He thus continued to proceed cautiously, responding to as much as creating events, although now taking more risks in order to chip away at Western power.

Events outside Europe greatly complicated the quest for a peaceful postwar order. In China, despite lavish US aid and notable Soviet restraint, the feeble Chiang Kai-shek government was collapsing before the resilient revolutionary forces led by Mao Zedong. The anticolonial struggles in the Dutch East Indies, British Malaya, and French Indochina also provided opportunities for communist penetration, weakening Western Europe and kindling alarm in Washington.

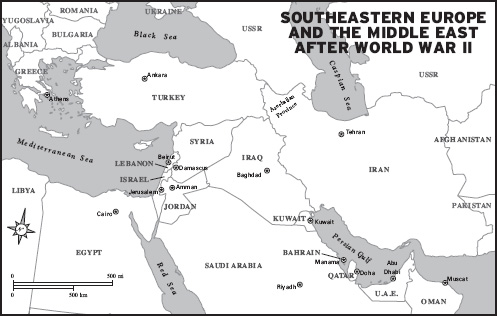

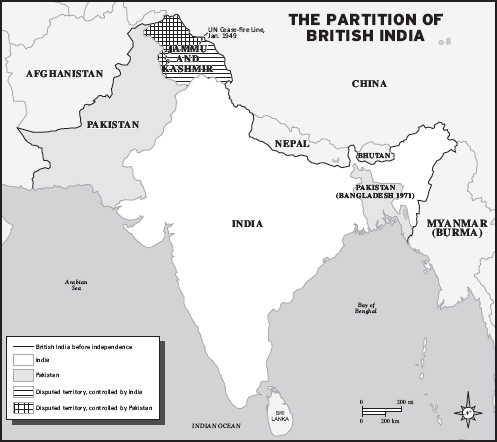

Moreover, the British Labour government’s decision to hastily withdraw from empire brought ethnic and religious violence to South Asia and the Middle East. The partition of the Indian subcontinent was followed by a ruinous civil war between Hindus and Muslims, creating millions of casualties and refugees and two rival successor states with ongoing border disputes: India and Pakistan (see Map 4).

The UN division of Palestine in November 1947 was also followed by an internecine struggle between Jews and Arabs. The communist bloc, perceiving an ally in the Zionist movement, provided crucial military supplies to the Jewish forces, but the United States, fearing to antagonize the Arabs, declared an official arms embargo. Israel’s declaration of independence in May 1948 and its subsequent military victory over four Arab states brought about the revival of Jewish statehood, but it also created an uneasy truce in the region. The United Nations assumed responsibility for some 750,000 Palestinian refugees, whose national aspirations had been crushed by the division of Palestine among Israel, Jordan, and Egypt (see Map 5).

The impact of decolonization and these civil wars was not fully understood by the Great Powers. Nonetheless, Truman and Stalin, although lacking global perspectives, recognized that the collapse of European empires would affect strategically important regions from North Africa to the Pacific and inevitably draw them in as rivals. Thus the United States moved to bolster stability in the Western Hemisphere with the Rio Pact in 1947 and the restructuring of the Organization of American States a year later. On the other hand, India’s proclamation of neutrality in the emerging Cold War offered newly independent states an alternative to joining the communist or capitalist blocs and even a means of provoking a bidding rivalry between the two.

Another unforeseen consequence of the changing postwar world was the attempt by nongovernmental organizations and small and medium-sized powers to transform the United Nations from a US-Soviet battleground into a site of human progress. One major focus—emanating from the promises in the Atlantic Charter and the atrocities of World War II—was the defense of human rights. These not always complementary goals—promoting freedom and self-determination for subject peoples on the one hand and shielding individuals and groups from arbitrary state power on the other—held little attraction for the Great Powers. At the Nuremberg trials the victors had been more intent on punishing the Nazis’ aggression than siding with their victims, and the same held true at the Tokyo tribunals. Although the UN Charter contained several references to human rights, the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union had frustrated human rights activists by blocking the inclusion of a universal bill of rights. Nonetheless, in 1946 the fifty-one-member General Assembly flexed its muscle, creating the Commission on Human Rights (CHR).

Despite the high expectations that attended its birth, the eighteen-member CHR was immediately dominated by Cold War realities. Its chair, Eleanor Roosevelt, was kept on a tight leash by the US government, which was intent on thwarting any binding obligations that interfered with “the internal problems of nations” and on using the commission’s forum mainly to castigate the Soviets’ misdeeds. The US and Soviet delegates both rejected the right to petition an international institution for redress of human rights violations by his or her government. The two Superpowers were also behind the CHR’s momentous decision to split its task into three separate components: the drafting of a nonbinding declaration of principles, followed—at some indeterminate interval—by the conclusion of a human rights convention, and, finally, the creation of a means of enforcement. The first task was completed within two years, but the second took twenty more, and the third still another year to come to life. By 1948 the Superpowers had effectively blocked the aspirations of human rights activists and smaller countries to derail the international order they intended to lead.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the product of the lopsided power relations in the CHR, was nonetheless a historic document graced with ringing language and high aspirations. It was not, however, a “universal” statement but based heavily on Western liberal philosophical and legal traditions. The UDHR not only placed the Soviets’ insistence on economic, social, and cultural rights in a secondary position but also omitted Asian and African claims to self-determination and rejected recognition of minority rights. Moreover, for over two decades it was a pledge without a means of enforcement.

Yet even as a nonbinding gesture, the UDHR gained worldwide currency. Its text permeated constitutions, treaties, and regional agreements and infused political language throughout the globe. Its principles buttressed the work of the UN agencies that protected labor, women, children, and refugees and stirred the General Assembly to annually reaffirm its commitment to human rights. And while Washington and Moscow considered the UDHR a minor weapon in their Cold War arsenals, other countries began to invoke its moral authority to protest racism and colonialism throughout the world.

For the United States and the Soviet Union, the prize was still in Europe, and in 1948 Europe’s East-West division hardened. In the Balkans, Albania, Bulgaria, Romania, and Yugoslavia had already fallen under communist control, but the Greek government, with US aid, was forcibly resisting a communist insurgency. Poland and Hungary had ended their brief periods of political pluralism with communist takeovers, although Finland and Austria were able to maintain noncommunist governments through prudent neutrality.* Czechoslovakia, the last surviving quasi-independent government east of Germany fell on February 28, 1948, almost ten years after the Munich agreement. The Prague coup—a brief, chilling, and largely bloodless episode of veiled Soviet threats, treachery by the local communists, and miscalculation by the anticommunists—destroyed the last remnant of Czechoslovakia’s sovereignty.

In stark contrast with the outcry in the media, Western leaders had already conceded Czechoslovakia (unlike Greece, Turkey, Italy, and Iran) to the Soviet sphere. Although Britain and France protested the communists’ seizure of power, there was no repeat of the Iran crisis, no urgent appeal to the UN Security Council.† Instead, public attention was focused on the danger of a Soviet military strike on the West. Asserting their will to defend themselves, Britain, France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands met in Brussels in March 1948 and, with Washington’s endorsement but no precise US commitment, signed a pact pledging mutual aid against foreign aggression.

Cooler Western observers construed the Prague events as a defensive move by Stalin. After the foreign ministers meeting in London (November–December 1947) had deadlocked over concluding a German or an Austrian peace treaty, the Western powers had decided to exclude the USSR from their decision making on Germany’s future. Indeed, two days before the Prague coup, the foreign ministers of Britain, France, and the United States had met in London and announced plans to raise coal and steel production in the Ruhr, create a separate West German state, and incorporate it into the Marshall Plan. The Soviets’ loud protests were ignored.

Map 6. By 1948 Europe was divided between East and West and would remain so for forty-one years.

Stalin also faced problems within his own camp. Fearing independent voices in Eastern Europe, the Kremlin removed Władysław Gomułka, an advocate of a “Polish path to socialism” and outspoken critic of the Cominform. A more formidable rival was Josip Broz Tito, the Yugoslav resistance leader whose wartime exploits and independent postwar policies had long frustrated the Kremlin. In June 1948 Stalin decided to punish Tito’s “nationalist deviationism”—particularly his alleged efforts to dominate the Balkans—by expelling Yugoslavia from the Cominform. Once more the Soviet leader miscalculated, not only failing to topple the Yugoslav chief but also—despite the heavy Soviet hand in the “anti-Titoist” purges and trials throughout Eastern Europe between 1948 and 1953—failing to stifle the genie of nationalism that would forever threaten communist unity. Moreover, after a cautious response to the Stalin-Tito rupture, the United States moved into the breach, offering aid to Yugoslavia in 1949 as a means of encouraging other communist dissident leaders.*

Moscow also suffered political setbacks in Western Europe, where the Cominform had encouraged widespread strikes in France and Italy that threatened two fragile governments but also stirred the ambitions of two highly independent communist parties. When Washington in late 1947 determined to use economic and political pressure to counter a perceived Soviet conspiracy, Stalin prudently backed off. In France, he stood by while the Americans orchestrated the secession of noncommunist labor leaders from the communist (CGT) union, the consequent reduction of the latter’s power and influence, and the stabilization of the Fourth Republic. In Italy Stalin reined in his most militant comrades, who were roundly defeated by the CIA-financed Christian Democrats in the April 1948 elections.

Not unexpectedly, 1948’s second crisis occurred in Berlin, the thorny relic of the Big Three’s wartime collaboration that lay one hundred miles inside the Soviet sector. Incensed by the introduction of the new Western currency (the deutsche mark) that would further separate the occupation zones, the Soviets angrily withdrew from the Allied Control Council in March. The announcement of the West’s intention to introduce the new currency in Berlin threatened to immensely increase the cost of the Soviet occupation that heretofore had been financed by inflated Reich marks. In response, on June 24, 1948, Soviet authorities cut off food, gas, electricity, and other supplies from the Western sectors and announced the closing of all road, rail, and water routes to and from Berlin.

Stalin, balancing the easy takeover in Prague with the communists’ setbacks in France and Italy, had made an imprudent gamble. By closing land access to the Western sectors, he had hoped to convince his ex-partners to return to the conference table or lose their place in Berlin. However, the British and Americans took up the challenge by instituting an extraordinary airlift, flying 278,000 sorties over the next eleven months that delivered some two million tons of food and fuel to the isolated outpost. They also instituted a punishing counterblockade against the entire Soviet zone.

The Berlin crisis occupies a special place in Cold War historiography, as an emblem of Soviet aggressiveness and Anglo-American resistance. It was nonetheless an extraordinarily calibrated confrontation. Truman, determined to avoid a military showdown, rebuffed advice to send in armed convoys, and Stalin refrained from attacking the Allied aircraft. Even when Truman announced the dispatch of sixty B-29s to Great Britain in July—aircraft capable but still not fitted to deliver an atomic bomb—the United States issued no direct threat against Moscow. Cold War mythology has also stressed the privations and stoicism of the West Berliners, who nonetheless received ample food and fuel from the local black market and from their eastern neighbors.

The crisis ended on May 12, 1949, when Stalin finally lifted the botched blockade, using the face-saving excuse of a foreign ministers’ conference, which, predictably, accomplished nothing. For eleven months Stalin had insisted on Moscow’s peaceful intentions and its fidelity to the Grand Alliance, but he lost the propaganda war. The West European press castigated the Soviet Union as an inept bully and praised the United States for its resolute defense of a beleaguered outpost.

Few at the time or since have questioned the costs or the risks associated with Berlin in 1948–1949. From that time until the end of the Cold War, the Allies’ presence in West Berlin remained the embodiment of Soviet frustration and, despite the city’s real vulnerability, of America’s commitment to halt aggression. Moreover, less than four years after World War II, two million West Berliners—and, by extension, the entire population of western Germany—were suddenly transformed into America’s democratic protégés. Truman’s actions in 1948–1949 replaced appeasement with firmness and selective engagement with an expansive definition of US interests and prestige. The Berlin airlift also redefined America’s view of its Cold War partnerships to include populations unwilling or incapable of defending themselves from aggression that would be rescued by decisive US action. In real as well as symbolic terms, the “Berlin syndrome” wiped out the Munich nightmare that had haunted the West for a decade.

Beyond a simple scorecard of political winners and losers, the Berlin crisis also had larger consequences. Both sides, after three years of demobilization, now began a vast and rapid buildup of their arms and military forces, including the reintroduction of the US military draft in June 1948. Second was the creation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). According to the treaty signed in Washington, DC, in April 1949, the Brussels Pact was expanded to twelve members, including the United States and Canada, who committed themselves to mutual defense against “aggressor(s) . . . with such action as [they] deem[ed] necessary.”* Despite the vagueness over its members’ actual military commitments, the birth of NATO—which, like the Rio Treaty, conformed to the UN Charter’s authorization of regional self-defense measures—demonstrated the West’s ultimate abandonment of the Grand Alliance. Unworried by Stalin’s protests (particularly over Italy’s membership), the West reminded Moscow of the mutual defense pacts that the Soviets had imposed on their small neighbors. If the Berlin crisis had demonstrated the Superpowers’ reluctance to go to war, it had also thickened the structures of their rivalry.

Many writers cite Stalin’s threat to Berlin as the catalyst for the division of Germany. The West’s resolve to end the fruitless haggling and create a German ally against the Soviets was undoubtedly facilitated by the blockade. However, the path to the creation of a West Germany involved more than simply detaching their zones from the Soviets. Germany’s western neighbors feared an entity that, with only 50 percent of the Reich’s prewar territory, would still outnumber France by fourteen million people and possess enormous industrial and military potential.

Thus there were political compromises in the creation of West Germany. Under Western tutelage the Basic Law, a preliminary constitution adopted by German officials on May 8, 1949 (the fourth anniversary of V-E Day), announced a total break with the Nazi past, creating a parliamentary democracy with strong human rights protection and the potential to collaborate closely with other governments as well as ensuring Allied occupation rights. France, which had failed to obtain the Ruhr industrial region or to suppress Germany’s economic revival, was mollified by the integrative conditions that gave extensive powers to the new German state governments (Länder), brought the western zones into the Marshall Plan, and maintained the US commitment to NATO. To assuage German nationalism (and neutralize Soviet propaganda), the Allies did not foreclose the possibility of future unification through free national elections and in the meantime allowed the new state to proclaim itself the sole legitimate representative of the entire German people (including the inhabitants of the eastern sector), to legislate on their behalf, and even to include Berlin within its jurisdiction.

On September 21, 1949, Stalin appeared to suffer a major political setback when the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG, or West Germany) was officially established. The Allies, ignoring Moscow’s loud protests over the violation of the Potsdam accords, recognized the new state, comprising ninety-six thousand square miles and a population of some fifty-six million. Two weeks later, on October 8, the Soviets set up the nominally independent German Democratic Republic (GDR, or East Germany), a state with almost nineteen million people and occupying territory of about 44 percent the size of its western neighbor. Stalin’s blunders, combined with deft Allied leadership and the cooperation of West German politicians, had enabled a potential colossus to arise in the FRG’s new capital in Bonn and West Berlin to remain free.

Map 7. The two German states between 1949 and 1990.

Yet Germany’s division in 1949 also offered advantages for Stalin, who as usual had a prepared fallback position. The two-state solution not only ended the uneven four-power negotiations, but also gave the Soviet Union a small but solid base from which it could exploit German labor, resources (particularly uranium), and chemical industries, and to station a half million troops in Central Europe without any constraints from the West. Some scholars believe that Stalin appreciated the symbolic value of achieving a communist domain in Germany, something that had eluded Lenin and one that would keep guard over Poland and Czechoslovakia. Although Stalin until his death never dropped his demand for a neutral, unified Germany,* the prospect of a military withdrawal from Central Europe may well have become less attractive than staying. If Soviet threats to West Berlin had failed miserably, other forms of pressure could still be applied.

The creation of two German states, an event unforeseen at Tehran, Yalta, or even at Potsdam, was a signal Cold War phenomenon. Foreshadowed by the dual occupation of Korea, Germany’s partition in 1949 combined both real and symbolic elements as a means of stabilizing Central Europe as well as a punishment for the Nazis’ crimes. Four-power occupation had worked in Austria—thanks to the smaller strategic stakes, a moderate socialist government, and the Allies’ Tehran decision to treat this country gently as “Hitler’s first victim”—and the country remained intact. In the more populous, resource-rich Germany, which lacked a central government, the occupiers were able to dominate the revival of local politics. East Germany became the first “workers’ and peasants’ state on German soil,” and West Germany a liberal, robustly capitalist state. Both regimes represented not only a renunciation of the Nazi past but also the revitalization of two opposing political traditions—Marxism and liberalism—each claiming redemptive power over Germany and Europe’s future and each mirroring the Cold War itself.

Whatever satisfaction the West reaped from its pragmatic solution to the German problem—and from the end of the bloody Greek civil war and Tito’s escape from Stalin’s grip into a US-supported Cold War neutrality—was undermined by two grave developments in 1949: the explosion of the first Soviet atomic bomb and the victory of Mao Zedong’s communist forces in China. Both, unexpected only in their speed, not only challenged America’s nuclear monopoly and its position in China but also appeared to strengthen the global revolutionary camp.

On September 23, 1949, Truman shocked the world with his announcement that the Soviet Union had secretly tested its first atomic weapon one month earlier.† Although the United States already had sufficient bases, aircraft, and bombs to inflict considerable damage on the Soviet Union, Moscow’s incipient nuclear arsenal stirred Western fears of political blackmail. Having long abandoned the effort for international control over nuclear weapons, Truman in January 1950 launched a large-scale program to develop the even more powerful hydrogen bomb, which was matched by an equally ambitious program by the Soviets.

The birth of the nuclear arms race in 1949 was imprinted in the history of the Cold War when both sides began committing vast resources to the production of arms capable of destroying not only the enemy’s military capacity but also the entire planet. The specter of preventive war that had loomed over the Soviet Union after 1945 was now matched by both sides’ hope that deterrence—backed by ever-growing stocks of nuclear weapons—would compel prudent behavior by their adversaries. Yet both sides also recognized that even the most powerful delivery systems might not be decisive in managing local conflicts and that armies still counted, especially in Europe. Moreover, the genies unleashed by nuclear testing and proliferation and by madman scenarios and civilian terror had the paradoxical effect of eroding the ideological distinction between the two Superpower rivals and kindling a global peace movement focusing specifically on the eradication of nuclear weapons.

Only eight days after Truman’s announcement another momentous event occurred: the formal establishment of the People’s Republic of China on October 1, 1949. The world’s most populous country had come under the rule of Mao Zedong’s communist forces. The US-supported Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek, which Roosevelt had envisaged as the fourth pillar of the postwar world, fled into exile on the island of Taiwan on December 8. From Washington’s perspective, the Soviets had greatly expanded their power and now threatened Japan and Southeast Asia.

The revolutionary dimensions of Mao’s victory were not well understood at the time and are still contested. Neither a grievous political defeat for the United States nor a great victory for the USSR, the establishment of communist rule in China exposed the limits of the Superpowers’ agility and skill. Locked in their rivalry over Europe in 1947–1948, both had failed to deal adroitly with the rapid deterioration of the Nationalist (Kuomintang) government and with the communists’ determination to prevail. In Washington, which was caught up in the close presidential campaign of 1948, the debate between the ardent proponents of military support for Chiang and the equally passionate decriers of his government’s corruption and ineptitude produced a $400 million aid appropriation but also a paralyzing fatalism over the US role in China’s future, particularly given the political impossibility of armed intervention. Similarly, in Moscow, the fears of US intervention and of a feisty Chinese Tito as well as the advantages of a weak and divided China that would preserve the Yalta gains had to be weighed against the ideological benefits of obtaining a huge Asian satellite. Stalin’s capricious gestures in 1948 were the result: a mediation offer that annoyed Washington and infuriated Mao and the delay in inviting the communist leader to Moscow, but also the intense communications between the two parties, the procommunist pronouncements later that year, and the stepped-up arms deliveries and diplomatic contacts in 1949.

The aftereffects of Mao’s victory were equally misread at the time. In Moscow on February 14, 1950, the Soviet Union and China signed a treaty linking 50 percent of the world’s land mass in a pact of friendship, alliance, and mutual assistance if either were involved in hostilities with Japan or its allies. China obtained significant concessions, including the retrocession within two years of the Changchun railway,* the return of Port Arthur (Lushun) and Dairen (Dalian), and the removal of Soviet extraterritorial privileges. Mao had to recognize the independence of Soviet-dominated Outer Mongolia, but he obtained Stalin’s permission to occupy Tibet, which he proceeded to do in the next year. Moreover, Stalin encouraged Mao to demand China’s seat on the UN Security Council and put pressure on the West by boycotting council meetings until this claim was fulfilled.

The 1950 pact between the two communist regimes reflected their unequal power and divergent national interests even more than their ideological solidarity. Despite the semblance of generosity and largesse, Soviet terms were tough. Moscow’s low-interest but modest $300 million credit for the purchase of Soviet industrial goods, to be granted in five installments, had to be fully repaid within ten years. Along with its agreement to create joint stock companies to exploit Chinese mineral resources, the Kremlin obliged Beijing to exclude other foreign investors. Finally, Stalin asserted his predominance over a regime he had neither anticipated nor energetically promoted by assigning to Mao the task of promoting anticolonial revolutions in Asia.

Cold War scholars disagree over whether the United States lost an opportunity in 1949–1950 to establish relations with the People’s Republic of China, particularly when its closest ally risked its ire and hastened to do so. The Atlee government, concerned over Hong Kong’s future, spurred by realist sentiment in the Commonwealth, and wishing to have a “foot in the door” when Sino-Soviet tensions would inevitably escalate, announced on January 6, 1950, its willingness to grant de jure recognition. Although France held back out of fear of Beijing’s threat to Indochina, two other NATO allies (Denmark and Norway) and three European neutrals (Sweden, Switzerland, and Finland) joined India, Indonesia, and Burma and ten communist governments in recognizing the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1950.

The United States stood back because of powerful political reasons—the widespread support for the exiled Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek in Congress, the press, and the churches—but also as a result of conflicting signals from Beijing. In May 1949, a few months before the communists’ victory, Zhou Enlai, Mao’s chief aide and one of the leading members of the Chinese Communist Party, had sent a conciliatory message through a third party that drew a suspicious response from Truman, who was peremptorily rebuffed by Beijing. One month later came an unofficial invitation to US ambassador John Leighton Stuart to hold talks with Zhou and Mao. But while this offer hung in the air, the Chinese were detaining the US consul general in Mukden on trumped-up charges of espionage.

Both sides, wary of the other and divided within, could not move forward until the verdict of Mao’s victory was delivered. The Chinese leadership was still distrustful of American imperialism and hamstrung by its pro-Soviet faction. America’s leaders, skeptical over uncovering a new Tito, feared manipulation by Beijing and were concerned over the actions of the third very interested player, the Soviet Union. Moscow, with good reason to fear another heretic, put extreme pressure on Mao to declare his solidarity.* The Chinese communist leader, whose exact sentiments cannot be known, undoubtedly bristled at the Kremlin’s behavior, but he could not ignore Stalin’s stranglehold over Manchuria or his own ideological commitment to Marxist unity. On June 30, 1949, Mao announced that China was “Leaning to One Side” and intended to ally itself with “the Soviet Union, with the People’s Democracies, and with the proletariat and the broad masses of the people in all other countries and form an international united front.” One day later, Secretary of State Acheson vetoed Stuart’s trip to Beijing.

Once the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was established, Washington chose a pragmatic policy between the two extremes of open hostility and conciliation. Combining balance-of-power concerns, ideological aversion, and fears for the safety of Chiang’s exile government in Taiwan, the United States refused recognition of the PRC and blocked its seating in the United Nations, but Washington did not stop others from opening embassies in Beijing or from breaking relations with Chiang Kai-shek.

Nonetheless, the Chinese revolution (following close after the explosion of the Soviet atomic bomb) intensified the Truman administration’s fears of communist expansion in Asia. Alarmed over the Vietnamese communist leader Ho Chi Minh’s February 1950 mission to Moscow, the Soviet decision to recognize his government, and Chinese support for the Viet Minh insurgency against French colonial rule, the United States swallowed its anti-imperialist sentiments and cast its lot with the Paris-backed puppet emperor Bao Dai.

Equally significant was the appearance in April 1950 of the National Security Council document NSC-68. This top-secret paper prepared by the State Department’s Policy Planning Staff, called for a major buildup of US military forces to counter the Kremlin’s threats to America’s interests in Europe and in Asia.* NSC-68 aimed at reassuring America’s allies of its resolve to halt the spread of communism, but it also channeled US Cold War diplomacy away from pragmatism and patience toward fear and frustration, and from Kennan’s watchful containment of the Soviet Union to an open-ended crusade against global communism.

The Cold War’s first hot war began on June 25, 1950. Following almost two years of armed skirmishes between North and South Korea, that day ninety thousand North Korean troops crossed the thirty-eighth parallel, easily captured Seoul two days later, and threatened to overrun the southern part of the peninsula. During the two preceding months, the North Korean communist leader Kim Il Sung had obtained Stalin’s assent and the Kremlin’s promises of military support for the invasion as well as an endorsement from Mao.† But the timing was the North Korean’s alone, and the invasion created a cascade of surprises for all the major parties.

In echoes of the 1930s, the United Nations now faced its first test of repelling military aggression against one of its members. Although dominated by a Western majority, the Security Council until then had been paralyzed by Moscow’s vetoes. But because of the six-month Soviet boycott over the UN failure to seat Communist China, the council on June 27 was able to adopt a US-sponsored resolution to provide South Korea (ROK) “with all necessary aid to repel the aggressors” and then to establish a UN expeditionary force under the command of US general Douglas MacArthur, to which sixteen nations ultimately contributed.*

Until June 1950 the defense of South Korea had not been part of America’s Asian strategy. Now the Truman administration, using the language of NSC-68, made it a symbol of the West’s “strength and determination” to resist Soviet aggression. Even before the UN resolution, Truman had hastily sent Japan-based US ground, naval, and air forces to South Korea. Washington, viewing the Korean crisis as an opportunity to protect the rest of Asia from falling as dominoes to communist expansion, also opted to support the French war in Indochina and moved the Seventh Fleet to the Taiwan Straits to shield the exiled Nationalists against a communist attack.† In Europe, the United States used the North Korean attack to urge its NATO allies to build a stronger barrier against Soviet aggression, one that would include West German rearmament.

Over the next three months the Korean War shifted dramatically. By early September the North Korean offensive had halted after a South Korean uprising never materialized, and UN soldiers, tanks, and aircraft began pouring in. After their spectacular landing behind enemy lines at Inchon on September 15, the UN troops went on the offensive, liberating Seoul and reaching the thirty-eighth parallel. At this decisive moment the Truman administration pressed the UN to approve a crossing into North Korea. With the announced aim of punishing the aggressors, US-led forces in the beginning of October moved northward toward the Yalu River, Korea’s border with China. Ignoring Beijing’s warnings, the United States aimed to solve the Korean problem by unifying the entire peninsula under a pro-Western government.

Stalin, although startled by Washington’s strong response, had initially refrained from intervening. Only after UN troops crossed the thirty-eighth parallel and North Korea appeared doomed did Stalin take action, urging Mao to aid their comrades and offering military support and Soviet air support (which did not, however, materialize until the summer of 1951). A resolute Mao fended off his politburo colleagues’ objections to launching a war with the world’s most powerful country, proclaiming his own domino theory of communist solidarity* and insisting that Korea was the most favorable terrain for China’s inevitable clash with the imperialist United States.

The Korean War again changed dramatically on October 19, 1950, when nearly three hundred thousand Chinese People’s Volunteers (CPV) crossed the Yalu River and drove the US Eighth Army southward. Seoul fell again in January 1951 but was recaptured by UN troops in March. Mao’s momentous decision to cross the thirty-eighth parallel (which Stalin strongly endorsed) led to a bloody two-year war of attrition until the July 1953 armistice agreement, which reset the two Koreas’ boundaries in a diagonal line extending only slightly north of the thirty-eighth parallel.

The Korean War also witnessed the first direct (if camouflaged) US-Soviet combat.† Beginning in late 1950, Soviet MiG-15s, based in Chinese air fields, joined their Chinese comrades in dogfights against US pilots accompanying B-29 bombing missions over North Korea. Also, some seventy thousand Soviet troops were stationed along the Yalu to provide air defense.

The costs of the Korean War were horrific. The country was devastated by massive US air strikes using bombs and napalm as well as by the three years of fierce fighting. Roughly three million (10 percent) of the Korean population were killed, wounded, or missing, including a very high number of civilians; thirty-seven thousand Americans lost their lives, along with three thousand other UN members; and some nine hundred thousand Chinese soldiers died. The casualty figures might have been worse had Truman acted on his initial impulse to use an atomic weapon.‡

The war’s political balance sheet was largely negative for all sides.§ The United States had repelled communist aggression but had succeeded in neither reunifying Korea nor ending South Korea’s vulnerability without a permanent UN occupation force. At home the Korean War created an inflationary spiral and a wave of anticommunist hysteria, and abroad it not only froze US relations with China for almost two decades but also expanded the Berlin syndrome and militarized American foreign policy in Asia. Moreover, by linking US policy with French colonialism in Indochina, the defeated Chinese Nationalists, and the highly unpopular South Korean president Syngman Rhee, Washington damaged its prestige among the newly emerging countries in Africa and Asia.

Stalin also had miscalculated. Having failed to anticipate Truman’s response and having goaded the Chinese to engage the United States, he now faced a major buildup of US military power, including the quadrupling of America’s defense budget and the doubling of its draft quota as well as the establishment of permanent US bases in Japan and South Korea, the increase in aid to anticommunist governments in Southeast Asia, and the strengthening of NATO with the addition of West German forces. The Korean War had seriously drained Soviet resources, and Moscow and its allies’ $220 million contribution to North Korea’s postwar reconstruction burdened their economies and created domestic discontent. Moreover, the aging and increasingly rigid Soviet leader failed to recognize that his callous exploitation of an impoverished and dependent China during the Korean War would sow the seeds of a Sino-Soviet split. China, although suffering enormous losses, deterred from capturing Taiwan, and forced to postpone its Five-Year Plan, had emerged from the Korean War with its international prestige greatly enhanced and as a potential rival to Moscow in the colonial world.

By the time the Korean armistice was signed on July 27, 1953, Joseph Stalin was dead, Harry Truman had been replaced by Dwight David Eisenhower, and a diplomatic revolution had occurred. The three former Axis states were now firmly in the Western camp, and the entire mainland of China had fallen within the Soviet orbit. Germany and Europe had become divided, and Asia and the Middle East were seething with anticolonial revolts.

The Korean War represented the gory culmination of seven years of Superpower probes of the other side’s aspirations, strength, and resolve. Each new test had led not to the provisional compromises that had sustained the Grand Alliance but to deepening their mutual suspicions, elevating their hostile rhetoric, and reinforcing their resolve to strengthen their respective camps. The near collisions in Berlin and the Korean War had added a military dimension, and the escalating nuclear arms race lent an element of rigidity and terror to US-Soviet encounters.

Nonetheless, the Korean War belied both sides’ hopes of attaining a preponderance of power: whether in wealth, military might, or ideological truth. The birth of a second communist state in China was a major challenge to their aim of dividing the world. Given the scale of political and social upheaval in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, neither the United States nor the Soviet Union could hope to impose its will everywhere on its own terms. Having gone almost to the atomic brink, the new leaders in Moscow and Washington in 1953 faced the challenge of building a less perilous, more orderly Cold War world that now extended beyond its original European borders.

Documents

Churchill, Winston. “The Sinews of Peace,” The Iron Curtain Speech, March 5, 1946. National Churchill Museum. http://www.nationalchurchillmuseum.org/sinews-of-peace-iron-curtain-speech.html.

Dedijer, Vladimir. Tito Speaks: His Self-Portrait and Struggle with Stalin. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1953.

“Marshall Plan.” 1948. National Archives and Records Administration Featured Documents. http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured_documents/marshall_plan.

“NATO Treaty, Washington, April 4, 1949.” Yale Law School Avalon Project: Documents in Law, History and Diplomacy. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/nato.asp.

Parrish, Scott D., and M. M. Narinskii. New Evidence on the Soviet Rejection of the Marshall Plan, 1947: Two Reports. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 1994.

Stokes, Gale. From Stalinism to Pluralism: A Documentary History of Eastern Europe Since 1945. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

“Trial of the Major War Criminals Before the International Military Tribunal, Nuremberg, 14 November 1945–1 October 1946.” Library of Congress Military Legal Resources. http://www.loc.gov/rr/frd/Military_Law/NT_major-war-criminals.html.

Truman, Harry. “Atomic Explosion in the USSR.” September 23, 1949. Yale Law School Avalon Project: Documents in Law, History and Diplomacy. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/decad244.asp.

Truman, Harry S., and Winston Churchill. Defending the West: The Truman-Churchill Correspondence, 1945–1960. Edited by G. W. Sand. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2004.

“The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Adopted by the General Assembly in December 1948.” United Nations. http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/index.shtml.

Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and Cold War International History Project. New Evidence on North Korea. Cold War International History Project Bulletin, Issue 14/15. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 2004. http://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/CWIHP_Bulletin_14–15.pdf.

Lippmann, Walter. The Cold War: A Study in U.S. Foreign Policy. New York: Harper, 1947.

Miłosz, Czesław. The Captive Mind. New York: Knopf, 1953.

Niebuhr, Reinhold. The Irony of American History. New York: Scribner, 1952.

Stone, I. F. The Hidden History of the Korean War. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1952.

X [George Kennan]. “The Sources of Soviet Conduct.” Foreign Affairs 25, no. 4 (July 1947): 566–582.

Memoirs

Acheson, Dean. Present at the Creation: My Years in the State Department. New York: Norton, 1969.

Dimitrov, Georgi. The Diary of Georgi Dimitrov, 1933–1949. Edited by Ivo Banac. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003.

Djilas, Milovan. Conversations with Stalin. Translated by Michael B. Petrovich. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1962.

Kennan, George F. Memoirs. Vol. 2: 1950–1963. Boston: Little, Brown, 1972.

Philbrick, Herbert A. I Led Three Lives: Citizen, “Communist,” Counterspy. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1952.

Truman, Harry S. Memoirs. 2 vols. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1955–1956.

Films

The Day the Earth Stood Still. Directed by Robert Wise. Los Angeles: Twentieth Century Fox, 1951.

Exodus. Directed by Otto Preminger. Los Angeles: Carlyle Productions, 1960.

The 49th Man. Directed by Fred F. Sears. Los Angeles: Katzman Corporation, 1953.

Gandhi. Directed by Richard Attenborough. Los Angeles: International Film Investors, 1982.

High Noon. Directed by Fred Zinneman. Los Angeles: Stanley Kramer Productions, 1952.

The Iron Curtain. Directed by William A. Wellman. Los Angeles: Twentieth Century Fox, 1948.

M*A*S*H*. Directed by Robert Altman. Los Angeles: Twentieth Century Fox, 1970.

On the Waterfront. Directed by Elia Kazan. Los Angeles: Columbia Pictures, 1952.

Pickup on South Street. Directed by Samuel Fuller. Los Angeles: Twentieth Century Fox, 1953.

The Red Menace. Directed by R. G. Springsteen. Los Angeles: Republic Pictures, 1949.

The Steel Helmet. Directed by Samuel Fuller. Los Angeles: Deputy Corporation, 1951.

The Third Man. Directed by Carol Reed. London: Carol Reed’s Production/London Film Productions, 1949.

Gouzenko, Igor. The Fall of a Titan. New York: Norton, 1954.

![]() abībī, Imīl. The Secret Life of Saeed, the Ill-Fated Pessoptimist: A Palestinian Who Became a Citizen of Israel. Translated by Salma Khadra Jayyusi and Trevor Le Gassick. New York: Vantage, 1982.

abībī, Imīl. The Secret Life of Saeed, the Ill-Fated Pessoptimist: A Palestinian Who Became a Citizen of Israel. Translated by Salma Khadra Jayyusi and Trevor Le Gassick. New York: Vantage, 1982.

Jin, Ha. War Trash. New York: Pantheon, 2004.

Rushdie, Salman. Midnight’s Children. London: Jonathan Cape, 1980.

Singh, Khushwant. Train to Pakistan. New York: Grove, 1956.

Secondary Sources

Banac, Ivo. With Stalin Against Tito: Cominformist Splits in Yugoslav Communism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1988.

Baylis, John. The Diplomacy of Pragmatism: Britain and the Formation of NATO, 1942–1949. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1993.

Bostdorff, Denise M. Proclaiming the Truman Doctrine: The Cold War Call to Arms. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2008.

Brogi, Alessandro. A Question of Self-Esteem: The United States and the Cold War Choices in France and Italy, 1944–1958. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2002.

Cardwell, Curt. NSC-68 and the Political Economy of the Early Cold War. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Chen, Jian. China’s Road to the Korean War: The Making of the Sino-American Confrontation. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

———. Mao’s China and the Cold War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

Cohen, Michael Joseph. Fighting World War Three from the Middle East: Allied Contingency Plans, 1945–1954. London: Frank Cass, 1997.

Corke, Sarah-Jane. US Covert Operations and Cold War Strategy: Truman, Secret Warfare, and the CIA, 1945–1953. New York: Routledge, 2008.

Craig, Campbell, and Sergey Radchenko. The Atomic Bomb and the Origins of the Cold War. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008.

Creswell, Michael. A Question of Balance: How France and the United States Created Cold War Europe. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006.

Dallas, Gregor. 1945: The War That Never Ended. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005.

Dallek, Robert. The Lost Peace: Leadership in a Time of Horror and Hope, 1945–1953. New York: Harper, 2010.

Deighton, Anne. The Impossible Peace: Britain, the Division of Germany and the Origins of the Cold War. Oxford: Clarendon, 1990.

Dower, John W. Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II. New York: Norton, 1999.

Eisenberg, Carolyn Woods. Drawing the Line: The American Decision to Divide Germany, 1944–1949. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Fawcett, Louise L’Estrange. Iran and the Cold War: The Azerbaijan Crisis of 1946. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Foot, Rosemary. The Wrong War: American Policy and the Dimensions of the Korean Conflict, 1950–1953. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1985.

Glendon, Mary Ann. A World Made New: Eleanor Roosevelt and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. New York: Random House, 2001.

Goda, Norman J. W. Tales from Spandau: Nazi Criminals and the Cold War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Goncharov, S. N., John Wilson Lewis, and Litai Xue. Uncertain Partners: Stalin, Mao, and the Korean War. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1993.

Gorlizki, Yoram, and O. V. Khlevniuk. Cold Peace: Stalin and the Soviet Ruling Circle, 1945–1953. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Gormly, James L. The Collapse of the Grand Alliance, 1945–1948. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1987.

Grose, Peter. Operation Rollback: America’s Secret War Behind the Iron Curtain. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000.

Harbutt, Fraser J. The Iron Curtain: Churchill, America, and the Origins of the Cold War. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

Hewison, Robert. In Anger: Culture in the Cold War, 1945–1960. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1981.

Hogan, Michael J. A Cross of Iron: Harry S. Truman and the Origins of the National Security State, 1945–1954. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

———. The Marshall Plan: America, Britain, and the Reconstruction of Western Europe, 1947–1952. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

Holloway, David. Stalin and the Bomb: The Soviet Union and Atomic Energy, 1939–1956. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1994.

Kaplan, Karel. The Short March: The Communist Takeover in Czechoslovakia, 1945–1948. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1987.

Kent, John. British Imperial Strategy and the Origins of the Cold War, 1944–49. Leicester, UK: Leicester University Press, 1993.

Klein, Christina. Cold War Orientalism: Asia in the Middlebrow Imagination, 1945–1961. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

Kuniholm, Bruce Robellet. The Origins of the Cold War in the Near East: Great Power Conflict and Diplomacy in Iran, Turkey, and Greece. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1980.

Lee, Steven Hugh. Outposts of Empire: Korea, Vietnam and the Origins of the Cold War in Asia, 1949–1954. Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1995.

Lees, Lorraine M. Keeping Tito Afloat: The United States, Yugoslavia, and the Cold War. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997.

Leffler, Melvyn P. A Preponderance of Power: National Security, the Truman Administration, and the Cold War. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1992.

Lewkowicz, Nicolas. The German Question and the International Order, 1943–48. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Lingen, Kerstin von. Kesselring’s Last Battle: War Crimes Trials and Cold War Politics, 1945–1960. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2009.

Loth, Wilfried. Stalin’s Unwanted Child: The Soviet Union, the German Question, and the Founding of the GDR. Translated by Robert F. Hogg. New York: St. Martin’s, 1998.

Louis, William Roger. The British Empire in the Middle East, 1945–1951: Arab Nationalism, the United States, and Postwar Imperialism. Oxford: Clarendon, 1984.

Lucas, Scott. Freedom’s War: The US Crusade Against the Soviet Union, 1945–56. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1999.

MacShane, Denis. International Labour and the Origins of the Cold War. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992.

Mastny, Vojtech. The Cold War and Soviet Insecurity: The Stalin Years. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

McMahon, Robert J. Colonialism and Cold War: The United States and the Struggle for Indonesian Independence, 1945–49. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1981.

Mitrovich, Gregory. Undermining the Kremlin: America’s Strategy to Subvert the Soviet Bloc, 1947–1956. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000.

Monod, David. Settling Scores: German Music, Denazification, and the Americans, 1945–1953. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Morris, Benny. The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947–1949. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

———. 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008.

Murray, Brian. Stalin, the Cold War, and the Division of China: A Multiarchival Mystery. Cold War International History Project Working Paper, No. 12. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 1995. http://wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/ACFB69.PDF.

Naimark, Norman M. The Russians in Germany: A History of the Soviet Zone of Occupation, 1945–1949. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1995.

Ninkovich, Frank Anthony. The Diplomacy of Ideas: US Foreign Policy and Cultural Relations, 1938–1950. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981.

Offner, Arnold A. Another Such Victory: President Truman and the Cold War, 1945–1953. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2002.

Qing, Simei. From Allies to Enemies: Visions of Modernity, Identity, and U.S.-China Diplomacy, 1945–1960. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

Roberts, Geoffrey. Stalin’s Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939–1953. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006.

Rucker, Laurent. Moscow’s Surprise: The Soviet-Israeli Alliance of 1947–1949. Cold War International History Project Working Paper, No. 46. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 2005. http://wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/CWIHP_WP_461.pdf.

Schwartz, Lowell. Political Warfare Against the Kremlin: US and British Propaganda Policy at the Beginning of the Cold War. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

Selverstone, Marc J. Constructing the Monolith: The United States, Great Britain, and International Communism, 1945–1950. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009.

Shlaim, Avi. Collusion Across the Jordan: King Abdullah, the Zionist Movement, and the Partition of Palestine. New York: Columbia University Press, 1988.

———. The United States and the Berlin Blockade, 1948–1949: A Study in Crisis Decision-Making. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983.

Siracusa, Joseph M. Into the Dark House: American Diplomacy and the Ideological Origins of the Cold War. Claremont, CA: Regina Books, 1998.

Spalding, Elizabeth Edwards. The First Cold Warrior: Harry Truman, Containment, and the Remaking of Liberal Internationalism. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2006.

Steininger, Rolf, and Mark Cioc. The German Question: The Stalin Note of 1952 and the Problem of Reunification. New York: Columbia University Press, 1990.

Stueck, William Whitney. Rethinking the Korean War: A New Diplomatic and Strategic History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002.

Tarling, Nicholas. Britain, Southeast Asia and the Onset of the Cold War, 1945–1950. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Taylor, Peter J. Britain and the Cold War: 1945 as Geopolitical Transition. London: Pinter, 1990.

Trachtenberg, Marc. A Constructed Peace: The Making of the European Settlement, 1945–1963. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999.

Tucker, Nancy Bernkopf. Patterns in the Dust: Chinese-American Relations and the Recognition Controversy, 1949–1950. New York: Columbia University Press, 1983.

Wagnleitner, Reinhold. Coca-Colonization and the Cold War: The Cultural Mission of the United States in Austria After the Second World War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994.

Westad, Odd Arne. Brothers in Arms: The Rise and Fall of the Sino-Soviet Alliance, 1945–1963. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1998.

———. Cold War and Revolution: Soviet-American Rivalry and the Origins of the Chinese Civil War, 1944–1946. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993.

Wettig, Gerhard. Stalin and the Cold War in Europe: The Emergence and Development of East-West Conflict, 1939–1953. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2008.

Yergin, Daniel. Shattered Peace: The Origins of the Cold War and the National Security State. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1977.

Young, John W. France, the Cold War, and the Western Alliance, 1944–49: French Foreign Policy and Post-War Europe. New York: St. Martin’s, 1990.

Zubkova, Elena. Russia After the War: Hopes, Illusions, and Disappointments, 1945–1957. Translated by Hugh Ragsdale. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 1998.

Zubok, V. M., and Konstantin Pleshakov. Inside the Kremlin’s Cold War: From Stalin to Khrushchev. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996.

![]()

* Mao Zedong, “The Present Situation and Our Tasks (December 25, 1947),” in Selected Works, 5 vols. (New York: Pergamon, 1961), 4:173.