THE WIDENING CONFLICT, 1953–1963

To govern is always to choose among disadvantages.

—Charles de Gaulle

Events are not a matter of choice.

—Gamal Abdel Nasser

In the decade following the carnage of World War II and Korea, most of the world experienced an extraordinary economic recovery as well as a striking diffusion of ideas and technology and record rates of population and GDP growth. In the noncommunist countries the Bretton Woods system created stable currencies and exchange rates, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) smoothed international commerce, and the IMF and World Bank began pouring resources into Africa, Asia, and Latin America, which provided the West with cheap and crucial raw materials. The Soviet Union, with the exception of its ties to China and North Korea, was slower than the United States to engage in trade outside its borders.

Europe’s revival was spectacular. In Western Europe, where the Marshall Plan had poured $13 billion into its recipients’ economies, a neo-Keynesian economic order was established in which governments used public spending and monetary policies to maintain strong and balanced economic growth. The Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, although constrained by tight financial, trade, and currency regulations, also made remarkable technological, industrial, and infrastructural gains.

Postwar Europe was nonetheless split by an Iron Curtain not only with barbed wire, mines, guard dogs, and machine guns but also with substantial political, material, and spiritual barriers. In communist Eastern Europe, up to Stalin’s death there had been major efforts to “engineer human souls” by emulating Soviet models promoting a socialist language, education, science, and aesthetics and rejecting decadent Western ways. The United States parried Moscow’s utopian message by exporting its consumer products, popular culture, and liberal political ideals. The most striking site of East-West cultural competition was in the rebuilding of Berlin. On one side of Hitler’s former capital rose the Stalinallee, a two-kilometer long, eighty-nine-meter wide boulevard with its monumental eight-story structures in the socialist-classicist style, and on the other the Hansaviertel, a neighborhood of brightly colored residential buildings designed by the world’s foremost architects in the international style.*

Both Superpowers used propaganda to penetrate their enemy’s territory. From the Kremlin came torrents of upbeat economic reports and antifascist diatribes as well as attacks on Western racism, capitalism, warmongering, and imperialism, which were echoed by Communist Party leaders and adherents in the West. The other side sent radio broadcasts in the national languages of Eastern Europe from the Voice of America, Radio Free Europe, and the BBC with news from the outside world; these encouraged the “captive populations” to seek freedom from Moscow’s domination.

The Iron Curtain was porous in other ways. Not only did Western and communist diplomats, businessmen, church groups, and labor unions maintain regular contacts, but by the mid-1950s a number of cross-border cultural, scientific, and university exchanges as well as sports competitions, although never removed from politics, established solid networks between East and West. Images and personalities also counted. Despite a decade of intense Cold War rivalry between their two governments, Soviet and American citizens were equally delirious over the twenty-three-year-old Texan Van Cliburn’s triumph in Moscow’s first Tchaikovsky piano competition, held in April 1958.

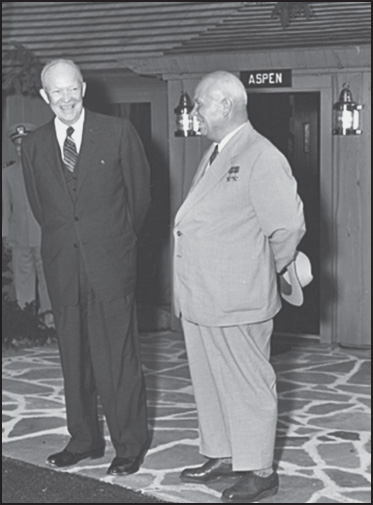

Two new leaders appeared on the scene. The new US president, Dwight David Eisenhower, was a veteran of two world wars, the architect of D-Day, and NATO supreme commander between 1950 and 1952; he came to office in 1953 promising a tougher stance toward the Soviet Union. The new Soviet chief Nikita Khrushchev was a Ukrainian-born metalworker who had served as a political commissar in the Red Army during the civil war, had risen rapidly through Communist Party ranks, and was again a commissar on the Ukrainian front in World War II. As party first secretary after Stalin’s death he deftly outmaneuvered his rivals Malenkov and Beria to attain almost complete power over the Soviet Union by 1955.

The other Cold War players fell into two camps. Whereas most European leaders* had been born in the nineteenth century, almost all the non-Europeans† had come to political maturity during World War II and had imbibed the promises of freedom and independence in the Atlantic Charter. The generational split was also evident in the cultural sphere. In both parts of Europe young writers and musicians began challenging their elders’ political and moral evasions under Hitler and Stalin and attempted to escape the Cold War straitjacket by embracing the romanticism and spirituality of the hero of Boris Pasternak’s novel Dr. Zhivago (1958) or the gruff unruly individualism of Oskar Matzerath in Günter Grass’s novel The Tin Drum (1959). Outside Europe, a new generation espoused the proud rebelliousness of Chinua Achebe’s protagonist Okonkwo in Things Fall Apart (1959), which shattered the image of “primitive” Africa and of its elders’ submission to imperialism.

The world of the 1950s drew closer through radio, via the new medium of television, and especially in the movie houses. The filmmakers of that decade produced striking universal narratives of love and violence, death and heroism, memory and forgetfulness, the strength of family bonds, the struggle against consumerism, and the power of myth and music.‡ Regional and foreign travel brought people together and created lasting bonds. From the glittering Sixth World Festival of Youth and Students in Moscow, held in July 1957 and attended by thirty-four thousand young people from all over the globe, came the prize-winning song “Moscow Nights” (“Podmoskovnye Vechera”), which transcended its Soviet origins to become a worldwide romantic anthem.

Popular movements spread throughout the globe. The United States in the 1950s gave the world rock and roll and blue jeans, the Beatnik lifestyle and the impudent figure of the Cat in the Hat, as well as the brave spirit and voices of its civil rights movement. Humanitarianism also connected rival nations. From Great Britain in 1959 emerged World Refugee Year, an international effort sponsored by the UN and joined by fifty-four countries in an effort to end the refugee problem through widespread publicity and innovative fundraising, political mobilization and private charitable efforts.

But the Cold War also intruded into popular culture. Some of the most striking moments occurred during the 1956 Sixteenth Summer Olympic Games in Melbourne, Australia. Not only were these the first televised games and the first to be held outside Europe and North America, but they also stood in the shadow of the Suez crisis and the Soviet invasion of Hungary (described later in this chapter).*

It was inevitable that the Superpower rivalry would spread beyond Europe, where the Cold War had reached a stalemate. Neither Washington’s “New Look”—the increased production of nuclear weapons and B-52 bombers to provide greater military capability at reduced cost—nor the extensive covert activities of the CIA were capable of rolling back the Soviet Empire in Eastern Europe. Indeed, the United States could only watch passively on June 17, 1953, when Soviet tanks crushed the East German protesters whom American propaganda had encouraged to break their chains. Similarly, Khrushchev, despite the Soviet Union’s increasingly impressive nuclear accomplishments, quickly recognized Moscow’s inability to dislodge the United States from Western Europe or to thwart the resurrection of an economically and politically strong West Germany, its entry into NATO, and its rearmament.

The former colonial world was a more promising arena for US-Soviet competition. With their large populations, crucial raw materials, and strategically important locations, Third World* countries represented a prime arena to launch a global contest between capitalism and communism. Beginning in 1953 Washington and Moscow, eager to supplant European control while advertising their own anti-imperialist credentials, formulated two rival economic development models accompanied by generous military and civilian aid packages and goodwill gestures (from student scholarships to high-level government visits) to attract the elites in the colonial and semicolonial states of Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America. Both deployed their overseas intelligence agencies, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the KGB, to enlist allies and informants in the Third World, monitor political movements and foreign governments, and penetrate their rivals’ activities.

Both sides entered this global competition with assets and liabilities, and both approached the Third World with a combination of ambition, altruism, and fear of the other’s gains. The United States, brimming with confidence over its role in rebuilding Western Europe and Japan, sought to extend its political influence by supporting the expansion of free markets and elected governments. The Soviet Union, which had revived spectacularly after World War II as a major military and industrial power, countered the West’s appeal with its call for centralized planning and a regime that promoted social and economic justice.

The United States embarked on this contest with a mixed record. Observers were distressed by the wave of virulent anticommunism that swept the country in the early 1950s and the bleak condition of its African American citizens. Abroad, America’s “pactomania,”† its hostility toward nonalignment, and its tendency to intervene in the affairs of its neighbors far and near raised alarm among Third World leaders. Particularly damaging to Washington’s reputation were the coups engineered by the Central Intelligence Agency against two elected foreign governments: in Iran in 1953, toppling a prime minister who had nationalized the country’s oil industry and returning Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi to power, and in Guatemala in 1954, replacing the popular left-wing president Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán, who had advocated extensive land reform and the expropriation of undeveloped foreign property, with a more compliant regime. The stereotype of the “Ugly American” was made famous by the 1958 novel and 1963 film depicting the US government’s clumsy efforts to outdo the communists in the rural hamlets of Southeast Asia.

The Soviet Union’s forays outside its borders were also fraught with problems. Echoing Lenin’s call for a global struggle against Western colonialism and neocolonialism, the USSR in the mid-1950s launched an ambitious foreign aid program in the Third World.* But at home, this initiative created problems, straining Moscow’s economic and financial resources at a time when Khrushchev was vowing to raise living standards and expand the Soviets’ military and nuclear capacity. Abroad, Khrushchev’s courtship of noncommunist Third World governments and his endorsement of a “hybrid” form of noncapitalist development (integrating state and private initiatives) weakened and disheartened Marxist militants in Egypt, Iran, Burma, India, and Indonesia. But above all, Khrushchev’s initiative left the Kremlin vulnerable to manipulation by ambitious Third World leaders and to a bidding contest with the wealthier West.

By the 1950s European imperialism was in full retreat in Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa. A spectacular note was sounded on May 7, 1954, when, after an almost two-month siege, the communist-led Vietnamese forces, backed by China, defeated the US-supported French army at Diên Biên Phu.† On July 21 the Geneva Accords ended more than six decades of French rule in Indochina. Laos and Cambodia became independent, and Vietnam, temporarily partitioned along the seventeenth parallel, was to hold national elections two years hence.‡

France’s disaster at Diên Biên Phu reverberated throughout the colonial world, particularly in French Algeria, where a nationalist insurrection erupted on November 1, 1954. Unlike Morocco and Tunisia (which it would grant independence in 1956), the French government was determined to maintain control over its largest possession, which had a million European inhabitants, immense natural resources, and more than a century of political, economic, and cultural ties with France. After the Soviet Union and China in 1955 endorsed the FLN (the Front de Libération Nationale, or National Liberation Front), the union of Algeria’s revolutionary factions, France, brandishing the specter of communism in North Africa, appealed for Washington’s aid. But the Eisenhower administration responded cautiously, wavering between support for its NATO ally and fears of alienating the Muslim world, between America’s decade-long Cold War reflexes and its growing recognition of a new world of emerging nations that were determined to avoid falling into either the communist or the Western camp.*

At the 1955 Bandung Conference, delegates representing twenty-nine states in Africa and Asia (one-fourth of the world’s land surface and 1.5 billion people) had declared their “common detestation of colonialism” and their adherence to the principles of nonalignment.† The ten-point Bandung declaration reaffirmed the charter of the United Nations, in all of whose agencies Asian and African members were now playing a major role, and also the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The Bandung meeting was a pivotal moment in the creation of a Third World identity. It drew an immediate endorsement from the Soviet Union, but one of its principal participants was communist China, which under its own revolutionary, anticolonial banner, was now vying with Moscow in the former colonial world.

Faced with rising Third World self-confidence, the United States began to reduce its hostility toward nonalignment (which Secretary of State John Foster Dulles had earlier denounced as “morally bankrupt”). Washington began to recognize the diminishing appeal of its multilateral security pacts, which had become tainted with a neocolonial label. In line with its earlier acceptance of Tito’s socialist form of neutralism, the United States—in order to compete effectively with the Soviets in Asia and Africa—began to woo independent Third World leaders.

Vietnam was an exception. The Eisenhower administration, which had refused to sign the Geneva Accords, feared a communist victory in the national elections and a domino effect throughout Southeast Asia. After the French withdrawal, the United States proceeded to build up a client state in the south, allowing President Ngô Ðình Di![]()

![]() m to cancel the 1956 elections and to clamp down on his opponents. Contrary to the Geneva Accords, which had forbidden the Vietnamese from entering foreign alliances or allowing foreign troops, Dulles mobilized the US-led Southeast Asia Treaty Organization to agree to protect South Vietnam against communist aggression. When a popular insurgency, which Di

m to cancel the 1956 elections and to clamp down on his opponents. Contrary to the Geneva Accords, which had forbidden the Vietnamese from entering foreign alliances or allowing foreign troops, Dulles mobilized the US-led Southeast Asia Treaty Organization to agree to protect South Vietnam against communist aggression. When a popular insurgency, which Di

![]() m contemptuously labeled Viet Cong (Vietnamese communists), erupted in the south two years later and received support from the north, Eisenhower expanded US economic and military aid and personnel on the ground.*

m contemptuously labeled Viet Cong (Vietnamese communists), erupted in the south two years later and received support from the north, Eisenhower expanded US economic and military aid and personnel on the ground.*

Nikita Khrushchev appeared to be a new Soviet boss. Seeking to counteract West Germany’s entry into NATO, the Soviet Union in May 1955 concluded the Warsaw Pact with its seven East European satellites, tying them tightly to the Kremlin and expanding Moscow’s voice in European affairs. But in that same year, Khrushchev also emitted conciliatory signals, reestablishing relations with renegade Yugoslavia, withdrawing Soviet forces from Austria, returning Soviet captured bases to China and Finland, and establishing diplomatic relations with the Federal Republic of Germany, including the repatriation of the remaining ten thousand German prisoners of war still held in the Soviet Union. At the Geneva Big Four meeting of Britain, France, the United States, and the USSR, ten years after the last Allied summit in 1945, Khrushchev uttered the words “peaceful coexistence.”

There were more surprises. Shortly after midnight on February 25, 1956, Khrushchev shook the communist faithful with his four-hour-long secret speech to the Twentieth Party Congress of the Soviet Union, in which he denounced Stalin’s crimes: the self-glorification and the cult of the individual that violated Leninist principles of collective leadership, the terror tactics against his enemies, the ruinous errors during the Great Patriotic War, the hideous postwar purges, and Stalin’s “suspicion and haughtiness [toward] whole parties and nations.”

Khrushchev’s secret speech, accompanied by the dissolution of the Cominform in April, and Tito’s visit to Moscow in June 1956 seemed to point to major reforms in the Soviet empire, but the new Soviet leader had no such intention. In response to nationwide anti-Soviet demonstrations in Poland between June and October and the return of the renegade Władysław Gomułka, Khrushchev planned a Soviet military strike, backtracking only in return for Polish assurances that the existing communist power structure would remain intact and the country would remain in the Warsaw Pact.

The Hungarian revolution posed an even greater challenge. By mid-October Hungary’s massive anti-Soviet demonstrations led by students, soldiers, writers, and workers had led to the disintegration of communist control. The newly appointed prime minister, Imre Nagy, a moderate party man who lacked Gomułka’s political agility, was swept along by the revolutionaries, suddenly announcing a multiparty system and Hungary’s withdrawal from the communist bloc.

The danger to Moscow was clear. An independent Hungary threatened to create a physical wedge in the Soviet Union’s East European empire, encourage imitators, and create a domino effect that would menace the homeland. Khrushchev, after a period of hesitation on the night of October 31 at the height of the Suez crisis (see the next section), gave the order to intervene militarily and reestablish reliable communist rule in Budapest.

The cost was substantial. Some 640 Soviet soldiers were killed and 1,251 wounded; on the Hungarian side were 2,000 dead, tens of thousands wounded, some 35,000 arrested, 22,000 incarcerated, 200 executed (among them Imre Nagy in 1958), and over 200,000 people who fled the country. Not only was Khrushchev’s stature at home and abroad greatly diminished, but he forced his country to assume the economic and political burdens of pacifying millions of resentful East European subjects through military occupation and with a less austere, more consumer-oriented (“goulash”) communism.

The Western public reacted strongly to the images of Soviet tanks crushing a popular uprising. Their governments promptly accepted thousands of refugees, and in a taunt to diehard Western leftists, the French political philosopher Raymond Aron declared in October 1956 that the Soviet Union was merely a “long-term despotism” that was doomed to fail.

Yet the United States, whose secretary of state John Foster Dulles for several years had preached the rollback of communism in Eastern Europe, had also suffered a moral defeat. Until the last moment, its paid radio broadcasters had imprudently encouraged the revolutionaries’ belief that outside support was imminent. Eisenhower, in the final days of his second presidential campaign and absorbed by the Suez crisis, was unwilling to risk a nuclear war over Hungary. Indeed, prior to the invasion Washington had sent reassuring signals to Moscow and declined to raise a protest in the United Nations. After the revolt was crushed and his reelection sealed, Eisenhower combined expressions of sympathy for the Hungarians’ plight with open acceptance of a divided and stable Europe, thus dispelling the myth of liberation and taking the first step toward détente in Europe.

Indeed, after 1956 the Cold War in Europe did change its face. The ideological confrontation became less aggressive. The doctrine of peaceful coexistence, repeated by Khrushchev at the Twentieth Party Congress, facilitated cultural exchanges between East and West. Westerners gradually discovered the films, literature, music, art, and scholarship from behind the Iron Curtain, while Soviet and East European citizens, increasingly exposed to Western visitors and ideas, continued to hope for less repressive, more humane socialism.

Although Moscow had secured its East European empire in 1956, its control over the world communist movement was diminishing. There were still loyalists to Stalin, such as the eighty-eight-year-old African American political philosopher W. E. B. Du Bois, who pronounced Khrushchev’s criticisms “irresponsible and muddled” and blamed the upheavals in Eastern Europe on US meddling. There were also new renegades, such as the Comintern veteran Palmiro Togliatti, leader of Italy’s second-largest party, who coined the term “polycentrism” to distance himself from the Kremlin’s dictates, and the Yugoslav dictator Tito, who again escaped Moscow’s clutches by embracing nonalignment.

The strongest response came from Beijing. Not only were Mao Zedong and Khrushchev mistrustful comrades, but the Chinese leader was appalled by the general secretary’s de-Stalinization campaign that had led to the tumult in Poland and Hungary. Stung by Moscow’s arrogance, tough economic terms, and lack of enthusiasm for liberating Taiwan, Mao also decided to pursue a more independent path.

By 1956, only four years after toppling the corrupt and ineffective King Farouk, Egypt’s second president and virtual dictator, the thirty-six-year-old Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser had become a major figure in international affairs. A champion of pan-Arabism, he aimed to build up Egypt and liberate the Middle East from the last vestiges of European colonialism. He had won Britain’s agreement to withdraw its eighty thousand troops from the Suez Canal Zone, played a starring role at the Bandung conference, and defied the West with a spectacular arms deal with communist Czechoslovakia in 1955 and the establishment of diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China in 1956.

By 1956 Nasser’s feats had also raised alarm. Israeli leaders, worried over their neighbor’s acquisition of sophisticated Eastern-bloc weapons, the escalating border violence, and the hostile propaganda emanating from Cairo radio, contemplated a preemptive strike. They found a kindred spirit in France, where the Guy Mollet government was obsessed with Nasser’s support of the Algerian revolution. And Britain’s prime minister, Anthony Eden, furious over Nasser’s attempts to undermine British interests in Iraq and Jordan, viewed the Egyptian leader as an “Arab Mussolini” intent on using Soviet aid to dominate the Middle East and to threaten Western Europe’s oil supplies.

The Superpowers were ineluctably drawn in. One year earlier, the United States, hoping to gain influence in the largest Arab state, had agreed to a generous $54 million loan to support the building of the Aswan High Dam. However, by the spring of 1956 Eisenhower had grown wary of Nasser’s flirtation with Moscow, his anti-Western statements, and his hostility toward Israel. Khrushchev on the other hand—despite his nod to noncapitalist development—was absorbed in the tumult in Eastern Europe and skeptical of the dam project and therefore declined Nasser’s request to enter a bidding contest with Washington. Suddenly, on July 19, an exasperated and suspicious Eisenhower withdrew the US loan, and Eden readily vacated Britain’s $14 million offer as well.

Shocked and humiliated, Nasser took action, announcing the nationalization of the Suez Canal to pay for the dam, stirring his compatriots, electrifying the Arab world, and triggering a prolonged international crisis. In a stroke, Nasser had attained a commanding position over the lifeline of Britain’s commonwealth and empire and over one of two principal routes of Middle Eastern oil deliveries to the West. With the closure of the Strait of Tiran, he had also gained a choke-hold on Israel’s maritime ties with East Africa and Asia.

The Superpowers’ responses were a study in contrast. Khrushchev, caught off balance by what he termed Nasser’s “ill-timed” move, neither spread a Soviet diplomatic mantle over Egypt nor offered additional arms, expecting the United States to rein in its allies. Thus during the next three months Eisenhower took the lead, striving to prevent an attack on Egypt, which, he was convinced, would destabilize the Middle East and encourage further Soviet moves into the region.

Pitted against the US president were his two agitated NATO partners: France, smarting over the loss of Indochina and the Algerian uprising and with a popular opinion solidly behind punishing Nasser, and Britain, with a divided cabinet and parliament and almost unanimous commonwealth opposition to the use of force, but led by an ailing and impulsive prime minister determined to assert his nation’s power and protect its oil supply. Israel played a crucial role. Prime Minister Ben Gurion, who had vacillated out of fear of US or Soviet intervention, was won over by militant cabinet members with the prospect of joining a Western alliance. In early October Eden agreed to Mollet’s audacious scheme for an Israeli invasion of Egypt as a cover for an Anglo-French seizure of the canal and the toppling of Nasser. Israel’s agreement to strike first was sealed in a secret pact with France and Britain signed at Sèvres on October 24, 1956.

Operation Musketeer began smoothly. On October 29 Israeli paratroops landed in the central Sinai and quickly reached the Suez Canal. One day later Britain and France issued a twelve-hour ultimatum demanding that both sides withdraw from the Canal Zone; when Nasser refused, on October 31 they bombarded Egyptian airfields, and after a five-day delay, their troops began ground operations. In the meantime Nasser had responded on November 1 by blocking the canal with blown-up craft and equipment. During that explosive week a wave of outrage swept the world, almost obliterating the dire news from Hungary.

It was now up to the Superpowers. Khrushchev was again taken unaware, having been lulled through October by Nasser’s overconfidence, faulty Soviet intelligence, and his underestimation of Eden’s resolve. Once hostilities began, Khrushchev, absorbed by Hungary, ignored Nasser’s pleas for military or diplomatic support, leaving the way open for US management of the crisis. Eisenhower, furious over his allies’ deception, was determined to halt the aggression against Egypt and to do so before Moscow acted. The United States called on the United Nations, and after an Anglo-French veto blocked action by the Security Council, the General Assembly on November 1 voted 64–5 in favor of an immediate cease-fire. In an extraordinary Cold War moment, Soviet and American aims had become identical and the United Nations became a site of peacemaking.

Both Superpowers overplayed their hands. With the Hungarian uprising almost crushed, Khrushchev on November 5 warned Eden, Mollet, and Ben Gurion that the Soviet Union was prepared to use its nuclear weapons “to crush the aggression and to restore peace in the Middle East.” Eisenhower, who had applied heavy political and economic pressure on the three belligerents, won both a second term and a cease-fire on November 6 and then took the lead in transporting a UN Emergency Force to Egypt and pressuring the invaders to withdraw their armies.

Map 9. The attack on Egypt by Israel, France, and Great Britain, October–November 1956.

Khrushchev’s saber rattling was alarming, but America’s desertion of its allies drew even heavier criticism at home and abroad. A humiliated Eden resigned, forcing Washington to reassure Britain and other NATO members of US protection and goodwill. France was even more disaffected over Eden’s yielding to Washington and Eisenhower’s nonchalance over Khrushchev’s threats. Musketeer’s author, Guy Mollet, resigned in May 1957, and the Suez fiasco undoubtedly prepared the way for the reemergence one year later of Charles de Gaulle, a leader imbued with a profound distrust of the Anglo-Saxons and determined to ensure France’s national security outside a US-dominated NATO and to build its own nuclear force.

The Suez crisis also produced the West’s first oil crisis. Almost immediately after Nasser blocked the canal, other Arab governments moved to choke the West’s oil supply. Syria severed diplomatic relations with Britain and France, and the pipeline carrying oil through its territory from Iraq to the Mediterranean was immediately disabled when three of its pumping stations were blown up, reportedly by units of the Syrian army. On November 6 Saudi Arabia also broke its ties with the aggressors and banned tankers from carrying its oil to Britain or France. Everything now depended on the United States, still a major oil producer and exporter as well as home to five of the seven multinational oil companies. An incensed Eisenhower refused to relieve his allies’ mounting oil shortages or rescue the plummeting British and French currencies until they withdrew their armies from Egypt.

To be sure, the oil scare had little impact at the time. Once Britain and France had caved in, the United States helped ease the delivery problem, and Anglo-American oil companies resumed their cooperation. Moreover, higher energy prices reduced consumption, and the unusually warm winter in Europe in 1956–1957 softened the impact of diminished supplies. By March 1957, the canal had been cleared, the pipelines repaired, and rationing ended in Western Europe. Worldwide oil production increased, and prices fell dramatically. Nonetheless, the specter of future shortages that could threaten the West’s security, halt its industries, and bring hardship to its population had presented itself in 1956, along with the lessons of US dominance over supplies and the Arabs’ willingness to use this weapon.

Israel, which had demonstrated its military prowess, emerged stronger from the Suez crisis. It now had a French ally willing to supply arms and even nuclear material. With strong French support it had secured an international guarantee of naval passage through the Strait of Tiran as well as a UN force to protect it against guerrilla raids from Egypt, although both gains were dependent on Nasser’s compliance. On the other hand, the exiled Palestinian leadership based in Gaza, which had witnessed the Egyptians’ rout firsthand, had become more determined than ever to pursue their goal of national liberation and sought more substantial Arab support. Israel’s relations with Washington had also soured: the United States had forced Israel to relinquish the prizes of its stunning victory—the capture of Gaza and the Sinai from Egypt—and to recognize its minor role in Eisenhower’s political calculations.

The Cold War had now spread into the Middle East. In the beginning of 1957 Eisenhower—echoing Truman ten years earlier—announced a new US doctrine, pledging military and financial aid to Arab countries threatened by the “spread of communism.” But Washington overestimated the Arabs’ fear of communism and underestimated their nationalism and political divisions along with their hatred of colonialism and of Israel. Meanwhile, Moscow, fixated on securing a foothold in a strategically important region, overestimated its resources and its influence over the Arabs and underestimated the US resolve to replace Great Britain as the major power in the region. The Suez crisis had demonstrated the readiness of Middle East actors to use the Superpowers but also the latter’s insufficient knowledge and understanding of the region’s populations and politics.

The best-selling 1957 novel On the Beach by the Anglo-Australian writer Nevil Shute was set in a world devastated by nuclear war. In that year the Superpowers had accumulated enough weapons not only to annihilate each other but also to make the globe uninhabitable.

Khrushchev’s nuclear bluff in November 1956 had been the threat of an underdog. The United States still held a clear superiority in strategic weapons: with nuclear bombs and long-range bombers outnumbering the USSR by a ratio of approximately 11:1. Moreover, the United States had encircled the Soviet Union with a chain of bases housing its Strategic Air Command bombers, which included 1,000 B47s, 150 B52s, and 250 B36s and were complemented by a worldwide fleet of aircraft carriers capable of launching long-range bombers from practically everywhere. Thus in 1956 the Soviet Union, with fewer bombs and aircraft, was vulnerable to a US first strike or a retaliatory attack, while the United States was still sheltered by numbers, distance, and a superior surveillance system.

Khrushchev was determined to overcome the Soviets’ inferiority. Alongside his calls for peaceful coexistence, he ordered a buildup in Soviet bombs and bombers and launched the development of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). With the appearance of the Sputnik satellite in 1957, thrust into space by a long-range Soviet rocket, the United States mainland suddenly became vulnerable to attack. Civil defense programs, which had already begun earlier in the decade, made Americans aware that Soviet rockets could now target any place on the globe. The Eisenhower administration hastened to regain US superiority by launching an ambitious space and missile program and providing government subsidies for higher education, especially in scientific and technical fields.

Europe stood precariously between the two Superpowers, and the Iron Curtain was its pervasive reality. Khrushchev’s threats in November 1956 and Eisenhower’s bland response had exposed Western Europe’s weakness. Despite the latter’s growing economic strength and the turmoil within the Soviet satellite nations, the Warsaw Pact’s ground forces outnumbered NATO’s by a ratio of about 6:1. Once mobilized and committed to war they could not be stopped before they reached the Rhine, even with the use of tactical nuclear weapons. Moreover, few West European leaders believed that the United States would expose its territory to retaliation by launching a nuclear strike against the Soviet Union.

West Europeans began to question two Cold War axioms: Was America’s nuclear umbrella reliable, or should their governments act more independently in their own defense? Did US bases endanger their crowded population centers and necessitate a reconsideration of NATO membership?

East Europeans raised questions as well. In a speech to the UN General Assembly on October 2, 1957, Polish foreign minister Adam Rapacki called for the de-nuclearization of Central Europe, which would have blocked the stationing of Soviet bases in Poland and Czechoslovakia as well as US bases in West Germany. Washington, although recognizing the significance of this independent initiative, promptly denounced the plan as a threat to NATO’s nuclear shield, a nonsolution to the German question, and a solidification of the Iron Curtain.

A global nuclear disarmament movement began to swell in the 1950s, drawing on memories of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, challenging the accelerating US-Soviet arms race, and bringing together people of different ages, races, and ideologies to demand a world free from the fear of a nuclear catastrophe.

Among the most anxious witnesses to the Hungarian and Suez crises was West German chancellor Konrad Adenauer. The Federal Republic, NATO’s newest member, had declared its neutrality in the war against Egypt, but it had been jarred by the Soviets’ brutal repression in Hungary and by Moscow’s threats to London and Paris as well as by America’s cavalier treatment of its principal European allies. Seizing the moment of his arrival in Paris on November 6, just as the cease-fire was announced, Adenauer urged his hosts to work together to “build Europe.”

The project of European unity had a long history and had gained force after World War II with the Marshall Plan and the European Coal and Steel Community, the 1951 agreement that had brought France, West Germany, Italy, and the Benelux countries (Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands) together under a common high authority. For more than a year the Benelux project of a Common Market—involving both economic and nuclear cooperation—had languished because of Franco-German hesitations, France over the future role of its empire and Germany caught in an internal debate over chaining itself institutionally and politically to its weaker neighbors.

The Suez crisis brought Bonn and Paris together in 1956 in a historic gesture of real and symbolic reconciliation. Adenauer believed that Western Europe needed to form a counterweight to the Soviet threat and American unilateralism, and Mollet wished to avenge the humiliation of Suez. The Treaty of Rome of March 25, 1957, which brought the European Economic Community (EEC) to life, grew out of a bargain involving substantial concessions to France’s overseas territories and a major financial commitment by Bonn, but it was also a clear sign of West Germany’s increased role in European affairs.

Britain’s future role in Europe was also affected. Eden’s successor, Harold Macmillan, accepted Britain’s economic and strategic dependency on Washington. He also reduced ties with Paris, repaired the frayed bonds with the British Commonwealth, and acknowledged that the “wind of change” was blowing through Africa. However, EEC membership held little appeal for London. Britain, already a nuclear power, was disinclined to share secrets and techniques with the continent. Moreover, it still sent 74 percent of its exports outside Europe, thus diminishing the attraction of submitting to the tariff and political controls of continental bureaucrats.

The six-member EEC developed into a significant US Cold War ally, although more robust in economic and cultural influence than in its military capabilities. Britain stood out until 1973, until its empire had disappeared and its economic isolation from the continent had weakened it further. In another unanticipated development, the Treaty of Rome not only created a supranational bureaucracy and expanded its members’ prosperity but also revived the dream of a whole, united, and democratic Europe that would exert a strong influence across the Iron Curtain.*

Khrushchev’s appeal for peaceful coexistence, echoing Lenin’s bid in the early 1920s, had evoked a cautious response from Washington. Indeed, the “spirit of Geneva” in 1955 had rapidly dissipated over Khrushchev’s bullying behavior in 1956, the ensuing Soviet arms buildup, and the general secretary’s boasts of the future global triumph of socialism. After Khrushchev had rejected Eisenhower’s Open Skies proposal* at the Geneva summit, the United States launched an ambitious aerial intelligence-gathering program involving high-altitude photoreconnaissance aircraft (U-2s) as well as the development of reconnaissance satellites to breach the barriers of the Soviets’ nuclear program and see beyond Khrushchev’s bluster.

The German question remained a fundamental source of contention among the World War II victors. After refusing the West’s 1955 proposals for national elections and a united Germany that would maintain links with NATO (with adequate security guarantees for its neighbors), Khrushchev had impulsively committed the USSR to preserving the independence and survival of East Germany (which Stalin had considered merely a Cold War bargaining card), thereby saddling Moscow for more than three decades with the burden of propping up and defending a weak, unpopular regime. Moreover the Berlin problem (the status of the divided former German capital lying one hundred miles inside the GDR) exacerbated East-West tensions. By the mid-1950s West Berlin had become a glittering showcase of capitalist prosperity that provided an easy escape route for almost two million disaffected East Germans. It was also militarily indefensible by its small US, British, and French garrisons—except at the cost of a nuclear war.

On November 10, 1958, Khrushchev provoked another Berlin crisis, emboldened by the successful coup in Iraq (which had overthrown the monarchy and removed that country from the British-organized Baghdad Pact) and by the peaceful outcome of the US-Chinese standoff over the Quemoy and Matsu islands (in which, he believed, his own quiet saber rattling had averted America’s nuclear threat to China). Almost ten years after Stalin’s failed probe, the Soviet leader threatened to repudiate the four-power occupation regime in Berlin and allow East Germany to control access to West Berlin. In his ultimatum he gave the West six months to negotiate their treaty rights with the German Democratic Republic. Khrushchev’s ostensible goal was to stabilize conditions in Central Europe: to crush Bonn’s hopes for unification, prop up the faltering GDR, and transform Berlin’s western sector—a “bone in the communists’ throat”—into an unarmed and vulnerable free city that, stripped of Western protection, would inevitably be swallowed by East Germany.

Once more a Soviet leader underestimated US determination to maintain its presence in Berlin. Ignoring British reservations over risking annihilation for the sake of two million former enemies, Eisenhower took a tough stand, exceeding de Gaulle’s strong response to Moscow’s threat, reassuring an anxious Adenauer, and maintaining West Berlin as a powerful symbol of American credibility. The Berlin crisis temporarily evaporated. In May 1959 Khrushchev let the deadline pass in return for a foreign ministers’ conference in August and an invitation to become the first Soviet leader to visit the United States in September.* At their meeting at Camp David, Khrushchev and Eisenhower agreed to put the Berlin problem “on ice” until the summit conference a year later. This represented a clear setback for the Kremlin, which had failed to halt the flight of East Germans westward—some 144,000 in 1959 and 200,000 would flee in 1960. It also raised concern in Beijing over Khrushchev’s growing coziness with the capitalists.

The spirit of Camp David was also short-lived. Both Eisenhower and Khrushchev were committed to reducing their nuclear stockpiles, but both were under pressure by their respective militaries to maintain sufficient bombs and missiles—the United States to stay far ahead, the Soviets to catch up—to prevent the other side from exerting nuclear blackmail. Eisenhower, urged by the intelligence community to inspect Khrushchev’s new ICBMs, in March 1960 reluctantly approved the resumption of U-2 reconnaissance flights—well aware that violating Soviet air space could compromise his efforts to achieve disarmament. On a particularly poorly chosen date, May 1, the annual celebration of International Workers’ Day and a major Soviet holiday, a U-2 was launched from Peshawar, Pakistan, on a 3,800-mile flight over the USSR to have ended in Bod![]()

![]() , Norway. Instead the craft, tracked by Soviet radar, was apparently forced by engine trouble to descend from its impregnable 70,000-feet altitude, and as it approached three of the Soviets’ five ICBM launch pads, it was shot down over Sverdlovsk in the Ural Mountains. The pilot, Francis Gary Powers, who had parachuted from the stricken plane, was captured immediately, and the wrecked U-2 plane went on display in Gorky Park near the center of Moscow.†

, Norway. Instead the craft, tracked by Soviet radar, was apparently forced by engine trouble to descend from its impregnable 70,000-feet altitude, and as it approached three of the Soviets’ five ICBM launch pads, it was shot down over Sverdlovsk in the Ural Mountains. The pilot, Francis Gary Powers, who had parachuted from the stricken plane, was captured immediately, and the wrecked U-2 plane went on display in Gorky Park near the center of Moscow.†

Only two weeks before the long-awaited four-power Paris summit to discuss Berlin and disarmament, the downing of the U-2 created a sensation. Eisenhower, dismissing his advisers’ counsel, on May 11 took full responsibility for the espionage flights, which he deemed a “distasteful but vital necessity” to guard the United States against “massive surprise attacks.” Khrushchev, infuriated by the president’s admission and determined to defend Soviet skies from foreign surveillance, demanded an apology, which Eisenhower refused. Thereupon the general secretary departed Paris on May 18, torpedoing the conference. In a vengeful gesture Khrushchev, en route to Moscow, stopped in East Berlin to reaffirm his commitment to “solving the German problem.”

Some observers have suggested that a major opportunity to end the Cold War was lost in May 1960; others strongly disagree. To be sure, neither the United States nor the Soviets were in agreement over the future of Germany; nor could they harmonize their views over disarmament, particularly in light of the pressures each had encountered from within and without. Eisenhower, nearing the end of his second term, had become increasingly alarmed over the power of America’s “military-industrial complex,” the vast public and private resources allocated to national security. On leaving office he admitted “a definite sense of disappointment” that no “lasting peace [was] in sight.”

Khrushchev’s efforts toward complete and general disarmament were also opposed, not only by members of the politburo and the Soviet military and intelligence elite but also by Beijing. After the failed Paris summit he marked time until Eisenhower’s departure and became more adventurous and truculent, courting Third World leaders, sending aid to the communist guerrilla movement in Laos and to the leftist regime of Patrice Lumumba in the Congo, and treating the world to a shoe-banging performance at the UN General Assembly in September 1960 in protest against the criticisms by the Philippines’ delegate of Soviet behavior in Eastern Europe. The stage was thereby set for a new and even more dangerous round of US-Soviet confrontation.

John F. Kennedy’s inaugural address on a wintry Friday, January 20, 1961, ushered in a new Cold War decade. The forty-three-year-old president, the first US leader born in the twentieth century, who had won the election by an extremely narrow margin, sent a mixed message. To Americans and the world he announced that “we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, in order to assure the survival and the success of liberty,” but he also held out the prospect of renewed disarmament negotiations with the Soviet Union as well as a global alliance to assure “a more fruitful life for all mankind.”

Khrushchev initially welcomed the new and pragmatic US leader, with whom he sought to settle the Berlin question once and for all and to continue the search for nuclear disarmament. Over Beijing’s strong objections, Washington and Moscow quietly cooperated in March to obtain a cease-fire in Laos and create a neutral government. In early April Khrushchev and Kennedy agreed to meet in Vienna in June. And on April 12 the Kremlin received another boost when the astronaut Yuri Gagarin became the first man to fly in outer space.

But a new barrier had been raised between the Superpowers. In January 1959 a revolution in Cuba led by the charismatic Fidel Castro had toppled the corrupt, US-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista. After Eisenhower, in retaliation for the nationalization of US landholdings, banks, and industries, imposed a crippling embargo, Castro turned to the Kremlin. Khrushchev in February 1960 grasped the opportunity to challenge the Monroe doctrine and enter the Western Hemisphere, offering to purchase Cuban sugar, grant low-interest loans, and provide substantial arms. Eisenhower, furious at Castro’s defiance—made explicit in his four-and-a-half-hour denunciation of “Yankee imperialism” before the September 1960 meeting of the General Assembly—and the appearance of thousands of Soviet technicians and military and diplomatic personnel, broke off relations with Cuba in January 1961 and handed his successor a plan to invade the island and overthrow its leader.

Kennedy, although skeptical, approved the operation. It involved a landing on three beaches of the Bay of Pigs by exiled Cubans, trained by the CIA and US Special Forces, who would ostensibly stir a revolt against Castro’s rule. However, at the last minute the new US president called off the air strikes that would have provided cover for the invasion force. Castro’s Soviet-supplied tanks and planes easily overwhelmed the invaders, who also had no local guerrilla forces to support their operation. A rueful Kennedy took full responsibility for the Bay of Pigs disaster, in which 1,100 survivors were taken prisoner in Cuba.

America’s second humiliation in two years formed the backdrop of the rough Vienna meeting in June 1961. Khrushchev, facing grim economic news at home, the collapse of his client Lumumba’s regime in the Congo, and growing Chinese defiance, issued another Berlin ultimatum that sent Kennedy reeling back to Washington searching for an appropriate response. Both sides decided on prudence. Kennedy, disregarding his senior advisers, urged an increase in the US defense budget and called up reserve troops and the National Guard, but he did not declare a national emergency. Khrushchev on his part had decided to avoid a nuclear showdown and to solve the Berlin problem in August 1961 by encasing West Berlin inside a concrete wall. By allowing the East Germans to erect this heavily fortified structure, Khrushchev closed off the last escape route from the Iron Curtain and saved the GDR.

The Western powers’ reaction was muted. Although protesting the limitations on inter-Berlin travel and communication, the United States, Britain, and France ultimately accepted the fait accompli that brought stability to the continent by removing the last dispute between Washington and Moscow. As Kennedy famously remarked to his aides, “A wall is a hell of a lot better than a war.”

For almost three decades the Berlin Wall became the Cold War’s most powerful symbol. In a surrounded West Berlin the West had gained an island outpost: a major intelligence site as well as a precious propaganda tool against communist repression. But for Chancellor Adenauer and West Berlin mayor Willy Brandt, the wall was also proof of America’s acquiescence in the division of their homeland and an important spur to pursue a more independent and dynamic German foreign policy.

Once the storm over Berlin had subsided, Khrushchev embarked on an even riskier initiative. By October 1962, with Castro’s approval, the USSR had begun construction of thirty-six medium-range missile and twenty-four ICBM sites in Cuba. Alerted by evidence from a U-2 overflight, Kennedy grimly informed the American public, announcing an air and naval “quarantine”* to block the arrival of additional nuclear armaments to Cuba, and demanding the removal of the existing missile sites while his administration secretly prepared for air strikes and an invasion of Cuba. With thirty Soviet ships headed for Cuba, the moment of a Superpower confrontation and a nuclear war seemed about to occur. Then both sides backed down, with Khrushchev agreeing to withdraw the missiles in return for an American pledge not to invade Cuba and to remove its missiles in Turkey.

For almost a half century US historians characterized Khrushchev’s action as an unprovoked threat to the United States and praised Kennedy’s courage and restraint in forcing a showdown and a unilateral Soviet withdrawal. However, recent research has modified this narrative. Khrushchev was, in fact, reacting to American aggressiveness toward his ally in Cuba* as well as the marked expansion of America’s military power after 1961, including the installation of intermediate-range Jupiter nuclear-armed missiles in Turkey that had sparked fears of a first strike against the Soviet Union.† By placing the missiles in Cuba Khrushchev had boldly gambled on giving the Americans “a little of their own medicine.”

Moreover, Kennedy, despite his public warning over the menace posed by the Soviet missiles, recognized that America’s vast nuclear preponderance was unaltered (even if its first-strike capability had now been curtailed). Sensitive to the political fallout over the missiles’ presence in Cuba, he responded with a display of brinkmanship that terrified the world, but he also refrained from the military showdown advocated by some of his advisers. And rather than inflicting a humiliating defeat, the president agreed to Khrushchev’s terms over the Jupiter missiles.

Instead of stabilizing the Cold War, the near collision between the Superpowers in October 1962 had a problematic outcome. Khrushchev, who had refrained during the crisis from threatening West Berlin, emerged all the more determined to achieve nuclear parity with the United States, whose growing fleet of reconnaissance satellites continued to patrol Soviet skies. And America’s NATO allies were less impressed with Kennedy’s resolution than stunned over the dangers they had faced because of Washington’s unilateral overreaction to a strategically insignificant event.‡ Indeed, bolstered by their growing economic prosperity—and with the status quo now cemented by the Berlin Wall—West European governments had become less frightened of a Soviet invasion and sought ways of improving relations with the Eastern bloc.

The nuclear alarm in October 1962 had the positive effect of prompting renewed efforts for strategic arms control. On June 20, 1963, the hotline agreement established direct communications between the White House and the Kremlin. In August the United States, Great Britain, and the soviet union signed a major treaty prohibiting nuclear testing in the atmosphere, in outer space, or at sea. But with the arrival of two new members in the nuclear club—France in 1960 and China in 1964 (which refused to adhere to the test ban)—the specter of proliferation shook Washington and Moscow.

With the construction of the Berlin Wall and the removal of the Soviet missiles from Cuba, each Superpower had halted the other’s incursions into their proper realms. Moscow’s Iron Curtain was reinforced in East Central Europe in 1961, and a year later the United States curtailed the Soviets’ military presence in the Western Hemisphere. After testing each other’s nerve and mettle—and taking the world to the brink of a nuclear war—John F. Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev suddenly disappeared from the international scene within a year of each other.

John Kennedy, who was assassinated in November 1963, left an ambiguous Cold War legacy. In his June 1963 American University commencement address he had expressed optimism over achieving peaceful coexistence with the Soviet Union. But within two weeks he set out to Europe to reassure his NATO allies of America’s commitment to their defense (while also appealing for a greater contribution on their part), and in West Berlin he denounced the brutal system on the other side of the wall and chided those who believed “we can work with the communists.” Moreover, the otherwise prudent Kennedy had markedly increased US military aid and advisers to the embattled government of South Vietnam and shortly before his death had also authorized the generals’ successful coup against Di![]()

![]() m, thus expanding America’s responsibility for another, even more distant, and indefensible ally.

m, thus expanding America’s responsibility for another, even more distant, and indefensible ally.

Khrushchev was toppled in October 1964 by a politburo disgruntled by his brinkmanship over Suez, Berlin, and Cuba and also opposed to his erratic search for coexistence with the United States. During his nine-year rule, Khrushchev had attempted to square the impossible: while striving to dismantle the repressive elements of Stalinism, he had used Stalinist measures to crush popular revolutions in Eastern Europe; while seeking to unify global communism, he had created a powerful rival in Mao’s China; while seeking to revive Marxist-Leninist revolutionary impulses in the Third World, he had not only raised Washington’s hackles but also embraced nationalist leaders who crushed their left-wing opposition; and while seeking détente with the United States and the end of NATO, his inflammatory language and nuclear threats had underscored the need for a united West.

Despite their differences in age and temperament, Kennedy and Khrushchev were both hardened Cold Warriors who only dimly recognized the radical changes in the world landscape that were beginning to reduce the Superpowers’ control. Their successors, less experienced in diplomacy and more intent on domestic reforms, would create a dangerous pause in the Superpowers’ post-Berlin, post-Cuba search for détente.

Primary Sources

“The 1956 Hungarian Revolution: A History in Documents: Electronic Briefing Book.” National Security Archive. 2002. http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB76/.

“Bay of Pigs Release.” Central Intelligence Agency. Last updated August 2, 2011. http://www.foia.ucia.gov/collection/bay-pigs-release.

“Berlin Wall.” Newsreel Archive. British Pathé. Accessed February 26, 2013. http://www.britishpathe.com/workspaces/rgallagher/Berlin-Wall-4.

Castro, Fidel. “Castro Speech Data Base.” Latin American Network Information Center. Accessed February 26, 2013. http://lanic.utexas.edu/la/cb/cuba/castro.html

“CIA and Assassinations: The Guatemala 1954 Documents.” National Security Archive. Accessed February 26, 2013. http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/guatemala/.

“Cuba Documentation Project.” National Security Archive. Accessed February 26, 2013. http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/latin_america/cuba.htm.

“Digital 1956 Archive.” Open Society Archives. Accessed February 26, 2013. http://osaarchivum.org/digitalarchive/index.html.

“Final Communiqué of the Asian-African Conference of Bandung (24 April 1955).” Centre Virtuel de la Connaissance sur l’Europe. http://www.cvce.eu/obj/final_communique_of_the_asian_african_conference_of_bandung_24_april_1955-en-676237bd-72f7-471f-949a-88b6ae513585.html.

“Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961–1963, Volume XI, Cuban Missile Crisis and Aftermath.” Office of the Historian, US State Department. http://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v11.

Kennedy, John F. “Inaugural Address, 20 January 1961.” John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Video, 16:00. http://www.jfklibrary.org/Asset-Viewer/BqXIEM9F4024ntFl7SVAjA.aspx?gclid=CPngl6eZyLUCFQ7NnAodaWcAhA.

———. “JFK’s ‘Cuban Missile Crisis’ Speech (10/22/62) (Complete and Uncut).” You-Tube video, 18:41. Posted by “DavidVonPein1,” December 15, 2010. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bOnY6b-qy_8.

———. The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis. Edited by Ernest R. May and Philip Zelikow. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1997.

Khrushchev, Nikita S. “Nikita S. Khrushchev: The Secret Speech—On the Cult of Personality, 1956.” Modern History Sourcebook. http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/1956khrushchev-secret1.html.

Nixon, Richard M., and Nikita S. Khrushchev. “Nixon-Khrushchev Kitchen Debate.” C-SPAN Video Library, 15:00. July 1, 1959. http://www.c-spanvideo.org/program/110721-1.

“The Secret CIA History of the Iran Coup, 1953.” National Security Archive. 2000. http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB28/.

“Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, Outer Space and Under Water.” Entered into force October 10, 1963. NuclearFiles.org. http://www.nuclearfiles.org/menu/library/treaties/partial-test-ban/trty_partial-test-ban_1963-10-10.htm.

“The U-2 Spy Plane Incident.” Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum. Accessed February 26, 2013. http://eisenhower.archives.gov/research/online_documents/u2_incident.html.

Djilas, Milovan. The New Class: An Analysis of the Communist System. New York: Praeger, 1957.

Kissinger, Henry. Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy. New York: Published for the Council on Foreign Relations by Harper, 1957.

Rostow, W. W. The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1960.

Wright, Richard. The Color Curtain: A Report on the Bandung Conference. Foreword by Gunnar Myrdal. Cleveland: World, 1956.

Memoirs

Dayan, Moshe. Diary of the Sinai Campaign. New York: Harper and Row, 1966.

Kennedy, Robert F. Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis. New York: Norton, 1969.

Khrushchev, Nikita Sergeevich. Khrushchev Remembers. Translated and edited by Strobe Talbott. Boston: Little, Brown, 1970.

———. Khrushchev Remembers: The Last Testament. Translated and edited by Strobe Talbott. Boston: Little, Brown, 1974.

———. Khrushchev Remembers: The Glasnost Tapes. Translated and edited by Jerrold L. Schecter and Vyacheslav V. Luchkov. Boston: Little, Brown, 1990.

Music

Cliburn, Van. “Van Cliburn.” YouTube video, 1:59, from a performance of “Moscow Nights,” 1958. Posted by “Posterfromus,” October 3, 2009. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s1vZWJT-XGw.

Hvorostovsky, Dmitri. “Dmitri Hvorostovsky Moscow Nights.” YouTube video, 3:25, from a concert recorded in Moscow, 2004. Posted by “Apomethe,” January 29, 2007. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mIHPhFHjn7Q.

Films

The Atomic Café. Directed by Jayne Loader, Kevin Rafferty, and Pierce Rafferty. Los Angeles: The Archives Project, 1982.

Ballad of a Soldier. Directed by Grigoriy Chukhray. Moscow: Mosfilm, 1959.

Battle of Algiers. Directed by Gillo Pontecorvo. Rome: Rizzoli Film, 1966.

Come Back, Africa. Directed by Lionel Rogosin. New York: Milestone Films, 1959.

Funeral in Berlin. Directed by Guy Hamilton. Los Angeles: Paramount Pictures, 1966.

Gigant Berlin. Directed by Leo de Laforgue. Berlin: Leo Laforgue Filmproduktion, 1964.

Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Directed by Don Siegel. Los Angeles: Allied Artists Pictures, 1956.

Kanal. Directed by Andrzej Wajda. Warsaw: Studio Filmowe Kadr, 1957.

On the Beach. Directed by Stanley Kramer. Los Angeles: Stanley Kramer Productions, 1959.

One, Two, Three. Directed by Billy Wilder. Grünwald: Bavaria Filmstudios, 1961.

Fiction

Arévalo, Juan José. The Shark and the Sardines. Translated by June Cobb and Raul Osegueda. New York: L. Stuart, 1961.

Beauvoir, Simone de. The Mandarins: A Novel. Translated by Leonard M. Friedman. Cleveland: World, 1956.

Beti, Mongo. Remember Ruben. Translated by Gerald Moore. London: Heinemann, 1980.

Carpentier, Alejo. Explosion in a Cathedral. Translated by John Sturrock. London: Gollancz, 1963.

Deighton, Len. The Ipcress File. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1963.

Fleming, Ian. From Russia with Love. New York: Macmillan, 1957.

Greene, Graham. Our Man in Havana: An Entertainment. New York: Viking, 1958.

Lederer, William J., and Eugene Burdick. The Ugly American. New York: Norton, 1958.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. A Grain of Wheat. London: Heinemann, 1967.

Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr Isaevich. One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. Translated by Max Hayward and Ronald Hingley. New York: Praeger, 1963.

Wright, Richard. The Outsider. New York: Harper, 1953.

Secondary Sources

Allison, Roy. The Soviet Union and the Strategy of Non-Alignment in the Third World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

Barghoorn, Frederick Charles. The Soviet Cultural Offensive: The Role of Cultural Diplomacy in Soviet Foreign Policy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1960.

Beschloss, Michael R. The Crisis Years: Kennedy and Khrushchev, 1960–1963. New York: Edward Burlingame Books, 1991.

Branch, Daniel. Defeating Mau Mau, Creating Kenya: Counterinsurgency, Civil War, and Decolonization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Castillo, Greg. Cold War on the Home Front: The Soft Power of Midcentury Design. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

Citino, Nathan J. From Arab Nationalism to OPEC: Eisenhower, King Sa’ud, and the Making of U.S.-Saudi Relations. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002.

Connelly, Matthew James. A Diplomatic Revolution: Algeria’s Fight for Independence and the Origins of the Post–Cold War Era. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Dudziak, Mary L. Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000.

Engerman, David C. Staging Growth: Modernization, Development, and the Global Cold War. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2003.

Freedman, Lawrence. Kennedy’s Wars: Berlin, Cuba, Laos, and Vietnam. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Fursenko, A. A., and Timothy J. Naftali. Khrushchev’s Cold War: The Inside Story of an American Adversary. New York: Norton, 2006.

Gati, Charles. Failed Illusions: Moscow, Washington, Budapest, and the 1956 Hungarian Revolt. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2006.

Giauque, Jeffrey Glen. Grand Designs and Visions of Unity: The Atlantic Powers and the Reorganization of Western Europe, 1955–1963. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Gilman, Nils. Mandarins of the Future: Modernization Theory in Cold War America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003.

Gleijeses, Piero. Shattered Hope: The Guatemalan Revolution and the United States, 1944–1954. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991.

Groys, Boris. The Total Art of Stalinism: Avant-Garde, Aesthetic Dictatorship, and Beyond. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992.

Harrison, Hope Millard. Driving the Soviets Up the Wall: Soviet–East German Relations, 1953–1961. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003.

Hixson, Walter L. Parting the Curtain: Propaganda, Culture and the Cold War, 1945–61. London: Macmillan, 1997.

Karnow, Stanley. Vietnam: A History. New York: Viking, 1983.

Kinzer, Stephen. All the Shah’s Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror. New York: Wiley, 2004.

Krenn, Michael L. Fall-Out Shelters for the Human Spirit: American Art and the Cold War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Kunz, Diane B. The Economic Diplomacy of the Suez Crisis. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

Kyle, Keith. Suez. New York: St. Martin’s, 1991.

Logevall, Fredrik. Embers of War: The Fall of an Empire and the Making of America’s Vietnam. New York: Random House, 2012.

Marsh, Steve. Anglo-American Relations and Cold War Oil: Crisis in Iran. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

Osgood, Kenneth Alan. Total Cold War: Eisenhower’s Secret Propaganda Battle at Home and Abroad. Lawrence: University of Kansas, 2006.

Poiger, Uta G. Jazz, Rock, and Rebels: Cold War Politics and American Culture in a Divided Germany. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

Puddington, Arch. Broadcasting Freedom: The Cold War Triumph of Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2000.

Rabe, Stephen G. Eisenhower and Latin America: The Foreign Policy of Anticommunism. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988.

Richmond, Yale. Cultural Exchange and the Cold War: Raising the Iron Curtain. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2003.

Rotter, Andrew Jon. Comrades at Odds: The United States and India, 1947–1964. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000.

Schlesinger, Stephen C., and Stephen Kinzer. Bitter Fruit: The Story of the American Coup in Guatemala. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, 2005.

Scott-Smith, Giles. The Politics of Apolitical Culture: The Congress for Cultural Freedom, the CIA and Post-War American Hegemony. London: Routledge, 2002.

Stern, Sheldon M. The Week the World Stood Still: Inside the Secret Cuban Missile Crisis. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005.

Tignor, Robert L. Capitalism and Nationalism at the End of Empire: State and Business in Decolonizing Egypt, Nigeria, and Kenya, 1945–1963. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998.

Von Eschen, Penny M. Satchmo Blows Up the World: Jazz Ambassadors Play the Cold War. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004.

Wang, Zuoyue. In Sputnik’s Shadow: The President’s Science Advisory Committee and Cold War America. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2008.

Wharton, Annabel Jane. Building the Cold War: Hilton International Hotels and Modern Architecture. Chicago: University of Chicago, 2001.

Wittner, Lawrence S. Resisting the Bomb: A History of the World Nuclear Disarmament Movement, 1954–1970. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1997.

Yaqub, Salim. Containing Arab Nationalism: The Eisenhower Doctrine and the Middle East. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Zhai, Qiang. China and the Vietnam Wars, 1950–1975. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

Zubok, V. M., and Konstantin Pleshakov. Inside the Kremlin’s Cold War: From Stalin to Khrushchev. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996.

![]()

* The international chain of Hilton hotels built in the 1950s also conveyed a cultural message. Conrad Hilton, whom the US State and Commerce Departments had encouraged to build his chain of grandiose pleasure palaces in the major cities of the world as “Little Americas,” called his modernist structure in West Berlin in 1958 “a new weapon with which to fight communism, a new team of owner, manager, and labor to confront the class conscious Mr. Marx.”

* Among them FRG Chancellor Konrad Adenauer (born in 1876), the GDR party chief Walter Ulbricht (born in 1893), French president Charles de Gaulle (born in 1890), British prime ministers Anthony Eden (born in 1897) and Harold Macmillan (born in 1894), and Yugoslav prime minister Josip Broz Tito (born in 1892).

† Among them Ahmed Sukarno (born in 1901) of Indonesia, Habib Bourguiba (born in 1903) of Tunisia, Kwame Nkrumah (born in 1909) of Ghana, Gamal Abdel Nasser (born in 1918) of Egypt, Nelson Mandela (born in 1918) of South Africa, and Fidel Castro (born in 1926) of Cuba. Important exceptions included Indian prime minister Jawaharal Nehru (born in 1889), Iranian prime minister Mohammad Mossadeq (born in 1882), and Kenyan revolutionary and first prime minister Jomo Kenyatta (born in 1894).

‡ These references are to the films La Strada, directed by Federico Fellini (Rome: Ponti-De Laurentiis Cinematografica, 1954); The Seventh Seal, directed by Ingmar Bergman (Stockholm: Svesnk Filmindustri, 1957); Hiroshima, mon amour, directed by Alain Resnais (Paris: Argos Films, 1959); Pather Panchali, directed by Satyajit Ray (Kolkata: Government of West Bengal, 1955); Mon Oncle, directed by Jacques Tati (Paris: Specta Films, 1958); and Black Orpheus, directed by Marcel Camus (Rio de Janeiro: Dispat Films, 1959).

* The Suez crisis in October–November delayed the torch relay from Greece to Australia, and the International Olympic Committee turned back calls by several Arab nations to bar Israel, France, and Britain from participating in the games.

Even more dramatic was the response to the Soviet invasion of Hungary. Spain, Switzerland, and the Netherlands boycotted the games. And at the notorious foul-ridden Soviet-Hungarian water polo match on December 6 the Hungarians won four goals to nil; the photograph of a blood-covered Hungarian athlete became a worldwide sensation.

* This term, evoking the underrepresented Third Estate in the French political order on the eve of the revolution in 1789, was first used in 1952 by the radical French economist Alfred Sauvy to characterize the aspirations of the world’s less powerful, more populous states to achieve the recognition and respect of the dominant minority. But by the 1960s the expression “Third World” also came to represent a group of states distinct from the capitalist West and the communist bloc.

† The name given to the Eisenhower administration’s efforts to link the United States with strategic areas of the world, forming alliances with forty-two states and treaty relations with nearly one hundred.

* Over the next fifteen years, Moscow extended some $4 billion in military and economic assistance to thirty-five countries, which included the dispatch of thousands of Soviet technicians, the granting of low-interest loans, and support for three giant development projects: the Bhilai steel complex in India, transport facilities and power plants in Afghanistan, and the construction of the Aswan High Dam in Egypt.

† By 1954, the United States was supplying 78 percent of France’s war materiel, but Eisenhower refused French pleas to use US air power, including tactical nuclear weapons, to lift the siege.

‡ Recent research in the Vietnamese archives has modified earlier accounts of Ho Chi Minh’s reluctant acceptance of partition because of Chinese and Russian pressure (neither wishing to prolong the fighting and reignite Cold War tensions with the United States). Because of his heavy losses, the need to consolidate his rule over the north, and the favorable prospects of winning the 1956 elections and unifying the entire country peacefully, Ho (perhaps making the best of a difficult political situation) claimed he had gained a “big victory” (thang loi lon) with the Geneva Accords.

* Significantly, the USSR was also cautious over Algeria. Khrushchev, who was attempting to woo France away from NATO, tempered his military support for the FLN with assurances of nonintervention in the “internal affairs of the French Union” and held off political recognition of the Algerian nationalists for several years.

† Despite the participants’ claims of their inclusiveness, several countries were excluded from Bandung because their presence would have been divisive: Israel, South Africa, and Taiwan as well as North and South Korea.

* Between 1955 and 1961 the United States poured more than $1 billion in economic and military aid to the Di![]()

![]() m regime, and by the time Eisenhower left office there were approximately one thousand US military advisers in South Vietnam.

m regime, and by the time Eisenhower left office there were approximately one thousand US military advisers in South Vietnam.

* On the other side of Europe was the eight-member Comecon (the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance), founded by Stalin in 1949 in response to the Marshall Plan, charged with regulating economic relations among the socialist states, and dominated by the Soviet Union.

* Aiming at overcoming the Soviets’ opposition to on-site inspection, the president had proposed a mutual exchange of blueprints and aerial photoreconnaissance.

* That summer Khrushchev had held his famous “kitchen debate” with Vice President Richard Nixon at the American National Exhibition in Moscow, the first high-level meeting between the Superpowers since 1955.

† The details of the May 1 crash—how exactly Powers’s plane was hit and also his failure to destroy the plane and himself—remain controversial to this day.

* Kennedy avoided the term “blockade,” which, according to international law, signified a state of war.

* Which included assassination plots, sabotage, and large-scale military exercises in the Caribbean aimed at toppling Castro.

† Which had been under consideration during the Berlin crisis in 1961.

‡ In the pithy words of French president de Gaulle: “annihilation without representation.”