THE SECOND COLD WAR, 1981–1985

Right now in a nuclear war we’d lose 150 mil. people. The Soviets could hold their loss down to less than were killed in W.W. II.

—Ronald Reagan, diary entry, December 3, 1981

In the end, the people’s will is what achieves victory.

—Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah

The second Cold War arose in the early 1980s, when the new US administration took the offensive—ideologically and strategically—against the Soviet Union. Unlike his immediate predecessors, who had viewed the USSR as a permanent presence in international affairs and an unavoidable if difficult partner, Reagan viewed the Soviet Union as an incorrigible adversary that he was determined to vanquish. In a 1982 UN speech Reagan condemned the USSR for violating human rights and spreading “political terrorism” throughout the world. That year he stunned the Soviets and his NATO allies by announcing the replacement of détente and peaceful competition with a “global campaign for democracy.” And in an address to the National Association of Evangelicals on March 8, 1983, Reagan described the Soviet Union as an “evil empire.”

Reagan matched his tough words with action. Taking aim at the 1968 Brezhnev doctrine (that the establishment of a communist regime was irreversible), the Reagan doctrine led to a substantial increase of US aid to anti-Soviet forces in Afghanistan and also to the opponents of Marxist regimes in Africa, Asia, and Central America. The US president even contested Soviet rule in Eastern Europe. In addition, Reagan directed the largest expansion and diversification of America’s military and nuclear forces since the late 1940s in order to establish US predominance and force concessions on the USSR.*

Reagan’s anti-Soviet crusade was supported by a substantial segment of the US public. Stung by Solzhenitsyn’s 1978 lament over the West’s loss of courage, many Americans yearned to reassert US strength and global leadership against the perceived Soviet advances of the 1970s. Reagan was also bolstered by the emerging neoconservative ideology in the United States that extolled capitalism and individualism and denounced the leftists’ creed of revolution and national liberation that had led to Stalin’s gulags, Mao’s Red Guards, and Castro’s tyranny, and had also shaped the welfare-state mentality that had caused Western economies to stagnate.

Moscow was duly alarmed over this major shift in US policy. Still a global power, the USSR was devoting an outsized portion of its resources to military spending and overseas aid and now faced an accelerated weapons competition with Washington. To be sure, foreign tensions also invigorated the Kremlin’s hard-liners. But Brezhnev (who died in November 1982) and his two short-lived successors, Yuri Andropov (who died in February 1984) and Konstantin Chernenko (who died in March 1985), tried futilely to interest Reagan in a summit meeting and a resumption of the arms-limitation negotiations.

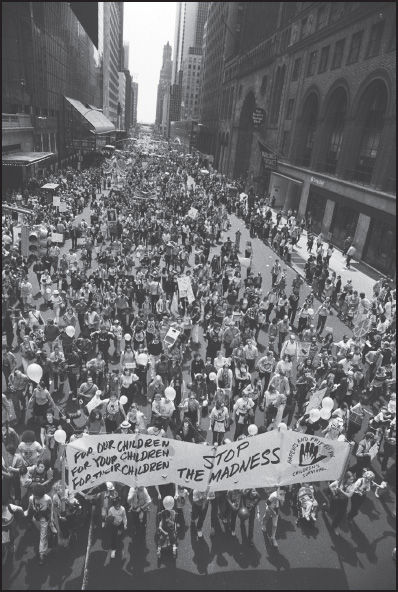

America’s NATO allies were also distressed by Washington’s unilateralism and the unraveling of détente. In Western Europe the antinuclear peace movement had revived and was strengthened in the early 1980s by a new generation of feminist, religious, and environmental activists.† Even China, although sharing Reagan’s antipathy toward Moscow, openly distanced itself from Washington’s anti-Soviet and Third World policies.

Moreover, Reagan’s drive to flay the Soviet Union with America’s overwhelming moral and military power arose in a far more complicated world than the 1940s and 1950s. By identifying the Afghan mujahideen and the Nicaraguan contras as “freedom fighters”‡ and lumping together the governments of Nicaragua, Libya, Ethiopia, Angola, Vietnam, and Cambodia, and the guerrillas in El Salvador, the PLO, and the rebels in Namibia as “Soviet proxies,” Washington blurred complex local and regional issues, which led to consequences beyond the Cold War itself.

THE DETERIORATION OF US-SOVIET RELATIONS

As the calendar approached George Orwell’s ominous year 1984, US-Soviet relations hit rock bottom. Not since the Cuban missile crisis had a Superpower conflict appeared this imminent. A series of mounting crises, which threatened to escalate beyond verbal denunciations, created some of the most dangerous moments of the Cold War.

General Wojciech Jaruzelski, who led Poland between 1981 and 1989, helped solve the Kremlin’s dilemma over the political crisis that had erupted in his country.* In the year following Brezhnev’s decision against intervention, Solidarność had become increasingly popular, organizing mass strikes and demonstrations, calling for democratic reforms and economic concessions, and threatening the collapse of communism in Poland as well as beyond its borders.† In Jaruzelski, a World War II veteran and minister of defense since 1968, Moscow found a loyal and tough comrade willing to save the Soviet Union the expense and international opprobrium of another invasion. On December 13, 1981, martial law was declared throughout Poland. Catching the opposition off balance, Jaruzelski proceeded to arrest the leaders of Solidarność as well as scores of other dissidents.

A startled Washington reacted swiftly and severely. In addition to declarations of outrage, the Reagan administration imposed stiff economic sanctions on the Warsaw government, banning the export of US agricultural products, suspending Poland’s most-favored-nation status, and blocking it from receiving assistance from the International Monetary Fund. To punish Moscow for the crackdown, the United States also halted grain exports to the USSR, suspended negotiations on scientific and technological cooperation, and prohibited the sale of American technology for the construction of the Soviet gas pipeline to Western Europe.

Although deploring Jaruzelski’s coup, West European leaders were riled by Washington’s unilateralism. German chancellor Helmut Schmidt and newly elected French president François Mitterrand protested the Reagan administration’s blow to the pipeline project—a major investment aimed at cushioning their economies against future oil shocks. Even British prime minister Margaret Thatcher, shocked by the repression but unconvinced that harsh methods would either bring the Soviet Union to its knees or alleviate Poland’s political and economic crisis, imposed far milder sanctions than Washington’s. America’s NATO allies were also irritated by US accusations of their dependency on communist regimes and quietly maintained their ties with the East.

China too was unreceptive to America’s campaign. However much Beijing welcomed any challenge to Moscow, Deng Xiaoping was uninterested in supporting Poland’s grassroots labor movement. Thus China threw its support behind Jaruzelski and actually increased its trade with Warsaw.

For the Soviet Union, the Jaruzelski solution was nonetheless a costly one. Western sanctions forced Moscow to spend billions of rubles to prop up Poland and also to purchase expensive grain on the world market, depleting its hard-currency reserves and exacerbating the consumer crisis in the USSR caused by the growing expense of the war in Afghanistan. Although Poland’s communist regime had been saved, the local military solution could only be temporary. Moreover, the vivid media reports of imprisoned Solidarność leaders and the onerous restrictions on personal freedom in Poland, bolstered by the press campaigns of the Vatican and US labor unions, had reinforced the Reaganites’ claim that the future belonged to the free world and that Marxism was headed for the “ash heap of history.”

Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI)

On March 23, 1983, in a televised address from the Oval Office, Reagan shocked the world (and his own administration) with his proposal to develop a new antiballistic system. Known as the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), its purpose was to shield the United States from the threat of a Soviet nuclear attack by “intercepting and destroying missiles before they reached our own soil or that of our allies.” Although the president’s proposal outlined a range of conventional defensive options (including land-based and submarine launchers), it was the space-based component that stirred the public: the computer-guided, ground-based, X-ray lasers and space-based antinuclear craft. Media critics immediately gave SDI the nickname “Star Wars,” permanently linking the president’s program with the popular 1977 science fiction film in which the forces of good employing advanced technology fought an evil empire.

Reagan’s extraordinary proposal to make nuclear weapons “impotent and obsolete” had several purposes. It was a strong and effective response to the peace offensive that had been launched by Brezhnev’s successor Andropov to resume arms negotiations. It was aimed at altering the president’s warmonger image without offering the Soviets any major concessions. SDI presented the prospect of an ingenious technological solution to assuage the public’s mounting terror of atomic warfare. It was also an attempt to neutralize the burgeoning nuclear-freeze movement that had taken hold in the United States.* And it was timed to convince Congress to pass another giant military budget.

But above all, SDI was inherently a move to extricate the United States from three decades of mutual deterrence, the principle that underlay the 1972 ABM treaty. Because neither the United States nor the USSR could defend more than a fraction of its territory, both had been dependent on the deterrent effect of the other’s strategic forces, reinforcing the concept of MAD (mutually assured destruction), in which the prospect of annihilation would prevent either side from going nuclear. Notwithstanding the improbability of its technical realization, SDI—by providing a one-sided defense from attack while leaving the other side vulnerable—altered the political as well as the strategic balance. For Reagan, SDI represented an escape from the “shackles of interdependence”: the abandonment of the principle of arms control and a one-sided US version of national survival. As such, it also posed a new and powerful threat to the economically and technologically weaker USSR.

The responses were predictable. Moscow was shocked and indignant. Already smarting over Reagan’s “evil empire” charge, Andropov accused the United States of seeking first-strike capability, extending the arms race into space, and using the threat of SDI to extract concessions from the Kremlin, and he warned of an “unprecedented sharpening” of the East-West confrontation. West European leaders not only questioned the technical feasibility of SDI and its breach of long-standing NATO defense policy but also quietly fretted over possible Soviet countermeasures. Even the usually loyal British warned against provoking “new instabilities and new arms races.”

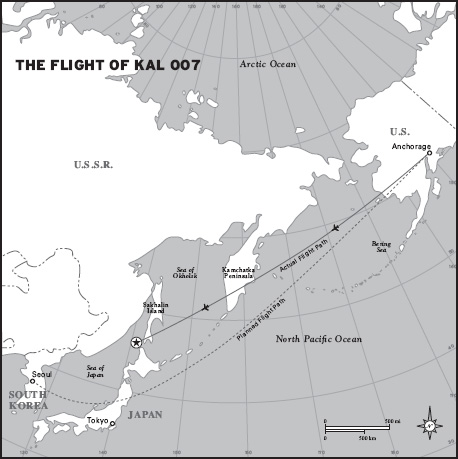

Hostility between the Superpowers continued to escalate. On the morning of September 1, 1983, US secretary of state George Shultz grimly informed the press that a missile fired by a Soviet aircraft had destroyed a South Korean airliner, whose 269 passengers and crew, among them 69 Americans (including a member of the House of Representatives), had been lost. One hour before the attack, KAL flight 007, which had inexplicably veered some two hundred miles off course, had strayed into Soviet airspace and flown over highly restricted missile and submarine bases on the Kamchatka Peninsula. The Korean airliner was immediately tracked by Soviet air defense units, which were on high alert because of repeated incursions by US fighter-bombers probing gaps and vulnerabilities in the Soviets’ early warning intelligence system as well as by periodic US surveillance flights, including one that same night by an American RC-135 reconnaissance plane. After crossing Sakhalin Island, another sensitive Soviet territory, KAL 007 was shot down over the Sea of Japan.*

Map 14. The route of the South Korean airliner in September 1983.

Although Reagan was absent from Washington, his administration rushed to condemn the Soviet Union. Based on hastily assembled US and Japanese intercepts of Soviet communications that clearly indicated the misidentification of the Korean craft, Shultz called it a deliberate “mass murder.” In his address to the nation on September 5, the president labeled the attack “an act of barbarism, born of a society which wantonly disregards individual rights and the value of human life and seeks constantly to expand and dominate other nations.”

The Kremlin, its leadership in disarray, responded poorly. Stunned by the Soviet military’s blunder and Washington’s overreaction, the politburo withheld an apology, constructed a feeble cover-up—insisting that the Korean aircraft was conducting a Washington-inspired espionage mission—and accused the United States of recklessly provoking “a global anti-Soviet campaign.” From his sickbed Andropov called Washington’s response “hysterical,” lambasted America’s “outrageous military psychosis,” and declared that war might come.

“White Hot, Thoroughly White Hot”*

The downing of KAL 007 was a striking manifestation of the revived Cold War. While Washington sought to embarrass Moscow and imposed diplomatic and legal punishments on the Kremlin, the Soviets retaliated by obstructing the search for survivors and denying their discovery in October of the plane’s black-box recording of its flight plan and communications.† This appalling accident stirred both sides not only to distort the facts and frighten their publics but also to restate their mutual grievances: the Americans against the heinous and irredeemable Soviet system, the Soviets against the unrelenting violation of their sovereign space and Washington’s obsession with using its military supremacy to blackmail Moscow.

For the first time since the Cuban missile crisis, the Superpowers appeared to be heading toward a confrontation. Each side, now possessing over twenty thousand nuclear warheads, had grown more and more nervous over the other’s increasingly menacing land and naval maneuvers. Fear and mistrust reached a peak in November 1983, when NATO’s military exercises created a panic in Moscow over a surprise nuclear attack.* That month, after the first US Cruise and Pershing missiles were deployed in Britain and Germany (some six to ten minutes’ striking distance from the USSR), Moscow halted the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) negotiations in Geneva and suspended the resumption of Strategic Arms Reduction Talks (START) with Washington. For the first time in more than a decade the Superpowers had ceased speaking to each other.

On November 20, 1983, The Day After, a television docudrama depicting the effects of nuclear war on a small Midwestern city, struck terror in a hundred million Americans.† Faced with a panicked public, a looming reelection campaign, and a bulging arsenal, Reagan suddenly reversed course. In his January 16 speech to the nation, the president called for renewed negotiations with Moscow and deemed 1984 “a year of opportunities for peace.” However, Andropov’s death in February and his successor’s infirmity (Konstantin Chernenko was suffering from severe emphysema) created a thirteen-month pause while US-Soviet relations neither improved nor deteriorated.

Although Reagan had been an outspoken opponent of the Helsinki Accords and a bitter critic of Jimmy Carter’s inconsistent human rights policies, he trod carefully in this delicate diplomatic terrain. His first secretary of state, Alexander Haig, who famously announced that “international terrorism will take the place of human rights,” adopted a conservative approach: promoting the evolution of friendly right-wing authoritarian regimes (such as Chile and South Africa) toward a more humane society and working to prevent the establishment of new totalitarian (i.e., communist) regimes that would inevitably repress their populations. Moreover, in dealing with Moscow’s ill-treatment of dissidents and religious and national minorities, Reagan was far more pragmatic than Carter, acknowledging the limits of US influence, declining to publicly “embarrass” the Soviets, and confining himself to personal letters to Brezhnev, private meetings with dissidents, and critical diary entries.

Reagan’s reticence stirred an immediate backlash from the human rights community, especially the US Helsinki Watch Group, which feared the loss of a powerful state ally. The US Congress, which since 1976 had compelled successive administrations to monitor global human rights, passed resolutions condemning Soviet misconduct and chastising Reagan for withholding public support for the oppressed. By the summer of 1982, after Shultz came to office, the State Department weighed in, rebuilding its human rights apparatus, formulating a program of public and private diplomacy, mobilizing America’s NATO allies, and raising America’s voice in the UN and at the CSCE conference in Madrid.* Meanwhile, US diplomats in Moscow and Leningrad maintained quiet contact with Soviet citizens who were denied permission to emigrate.

But Reagan, still more intent on military and ideological mobilization, was reluctant to wave the human rights banner. To appease the activists, between 1981 and 1983 he responded with showy gestures, increasing funds for Voice of America and Radio Liberty; designating special days for Americans to honor Solidarność, the people of Afghanistan, and the Soviet dissident Andrei Sakharov; and reviving Baltic Freedom Day and Captive Nations Week. But Reagan refused to use tougher methods—wielding the trade weapon or terminating cultural exchanges—to modify the Soviets’ behavior.

There was an ostensible shift in US policy in 1984. In his otherwise conciliatory January 16 speech, the president for the first time identified human rights as a “major problem” in US-Soviet relations, expressed America’s “deep concern over prisoners of conscience in the Soviet Union and over the virtual halt in the emigration of Jews,† Armenians, and others who wish to join their families abroad,” and called on the Soviet Union to live up to its Helsinki obligations. Yet despite the president’s reputation among Soviet dissidents as a liberator, it is probable that he was responding to election-year domestic pressures and continued to believe that the most effective way to alleviate the plight of Moscow’s victims was to demolish the entire Soviet system.

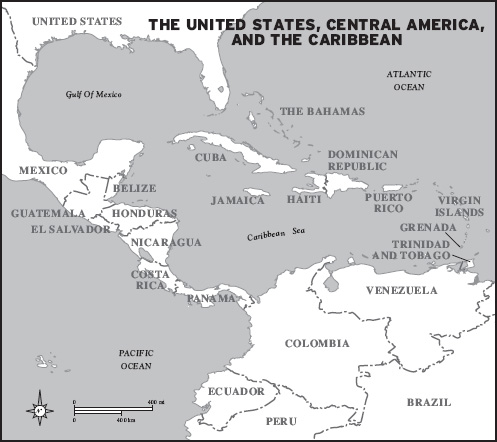

Cold War tensions were also reignited in the Western Hemisphere. The Kremlin, although reluctant to increase its already heavy military and economic burdens, was still committed to supporting left-wing (in its own parlance “progressive”) Third World movements, including those in Washington’s own backyard. The Reagan administration, convinced that communism was on the rise in Central America, abandoned Carter’s efforts to curb human rights abuses by pro-US rulers and devoted an unprecedented amount of time, effort, and resources to asserting American power in the region.

Beginning in 1981 Washington provided substantial assistance to the military governments of El Salvador and Guatemala to fend off leftist insurgencies. But the president’s principal target was Nicaragua, which he labeled a communist and totalitarian regime and was determined to overthrow. To punish the Sandinista government for funneling Soviet and Cuban arms to the guerrillas in El Salvador, his administration cut off all aid to Managua. In addition, Reagan authorized covert CIA actions* and provided funding, training, equipment, and logistical support to the Honduras-based paramilitary opposition (contrarevolutionarios), known as the Contras. Faced with Washington’s challenge, the Soviet Union greatly increased its military and economic assistance to Nicaragua, which also received aid from Western Europe and other Latin American countries.

The ensuing violence in Central America shocked the world public. In the US-supported counterinsurgency in Guatemala, the military destroyed hundreds of villages and hamlets, killed between fifty thousand and seventy-five thousand people, and created a million refugees; in tiny El Salvador the rulers’ death squads left seventy thousand dead and hundreds of villages destroyed; and in Nicaragua the Contras, after failing to defeat the Sandinista army, resorted to widespread terrorist attacks against civilian targets in a war resulting in thirty thousand deaths, a hundred thousand refugees, and a ruined economy. By 1983, the Democrat-controlled US Congress, fearing another Vietnam, sought to curb Reagan’s anticommunist crusade in Central America, reducing aid to Guatemala and El Salvador, refusing to fund the Contras, and ruling out the use of American troops.

Undeterred, the Reagan administration took bold action elsewhere. In the first US military intervention in the Western Hemisphere in eighteen years,† the president in October 1983 launched an air, land, and sea invasion of the tiny Caribbean island of Grenada for the purpose of toppling its Marxist government. Having secured marginal support from the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States, Washington announced its goals as protecting American medical students, thwarting the construction of a ten-thousand-foot airfield that could be used by Soviet or Cuban military aircraft, and restoring law and order and democratic institutions to Grenada. Seven thousand US troops easily overwhelmed the six-hundred-man Grenadian army and some seven hundred Cubans and installed a pro-US regime.

The American intervention in Grenada conveyed a clear Cold War message. In addressing the nation on October 27, Reagan underlined the Soviet Union’s responsibility for the spread of subversion in the Caribbean (and also linked Moscow with the bombing of the marine barracks in Beirut four days earlier), and he reiterated his commitment to fight terrorism and roll back world communism. Although Andropov issued only a mild protest against the invasion, the Kremlin was stunned by Washington’s use of military power. Cuba removed some one thousand personnel from Nicaragua, and the Managua government was put on notice of the consequences of provoking Washington.

International reaction was largely negative. Although the United States was able to veto a Security Council resolution, the UN General Assembly, by a lopsided vote of 108–9, condemned the invasion as “a flagrant violation of international law.” The British government, fending off public criticism of the cruise missile deployment, took a dim view of Reagan’s Big Stick diplomacy, which harked back to Theodore Roosevelt’s assertion of the moral imperative of US dominance. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, whom Washington had not consulted beforehand, as leader of the British Commonwealth of Nations (of which Grenada was a member) publicly opposed the invasion.

The heightened risks of unilateralism and the erosion of multilateral peacekeeping had already been exposed a year earlier by the Falklands War, the world’s first major naval engagement since World War II. This seventy-four-day conflict had pitted two US Cold War allies, Britain and Argentina—one a key NATO member, the other an active anticommunist partner in Central and South America—in a dispute over sovereignty of a remote group of South Atlantic islands.* Because of mounting tensions, the Superpowers were incapable of bringing the two countries to the negotiating table and avoid a war that cost a thousand lives.†

Indeed, the Falklands War was more than a remote sideshow, and neither Superpower exhibited adroit statesmanship. The United States sided with the British: the Reagan administration provided a satellite communications channel for their warships and stymied efforts by the UN and the Organization of American States‡ to mediate the conflict. By doing so it provoked considerable resentment in Argentina and the rest of Latin America as well as in non-Western countries without incurring much gratitude from Thatcher. For the Soviets, the Falklands War provided a welcome distraction from their troubles in Poland and Afghanistan, an opportunity to lambaste Western colonialism, and a glimpse at the performance of British NATO forces. Nevertheless, Moscow failed to gain credit in the Third World because of its refusal to provide aid to Argentina (which had been an important grain supplier during the US embargo) and its failure to stand up to the West in the Security Council. The Falklands War not only revealed the Superpowers’ continuing indifference toward multilateral peacekeeping but also the limits of US and Soviet control over conflicts precipitated by desperate and determined third parties.

The renewed Cold War of the early 1980s also affected Asia. With the demise of détente, Moscow and Washington stepped up their competition to woo China and play a major role in Asia, but these efforts were complicated after the People’s Republic under Deng Xiaoping launched a “second revolution” that established market-oriented economic reforms at home and an independent voice abroad. Resolved to back neither Superpower, China used its permanent Security Council seat to reaffirm the 1955 Bandung principles of anticolonialism and peaceful coexistence.

Both Superpowers approached Beijing with serious liabilities. The Reagan administration was initially cool toward the People’s Republic, because of the president’s long-standing anticommunist stance and his commitment to Taiwan, and China not only was adamantly against Washington’s arms sales to its opponent but also critical of America’s interventionist policies in Central America, Africa, and the Middle East. The Kremlin, now facing a potent rival promoting an alternative model of economic development in the Third World, nonetheless hoped to exploit the Sino-US rift and repair its broken ties with Beijing, but it was thwarted by China’s three demands—the Soviets’ withdrawal from Afghanistan, a Vietnamese withdrawal from Kampuchea (Cambodia), and a rollback of the Soviet military buildup on its northern borders, which included fifty divisions and SS-20 intermediate-range ballistic missiles.

Deng Xiaoping, facing a divided politburo and immense domestic challenges, trod warily in international affairs, evenhandedly resisting Washington’s pleas for a more belligerent anti-Soviet stance* and Moscow’s offers for a nonaggression pact. In 1984 Beijing hosted two high-level visitors: in April Ronald Reagan (who later claimed to have fallen under a “China spell” and lauded its government for embracing “capitalist principles”) and in December Soviet first deputy prime minister Ivan Arkipov (the highest-level contact since Kosygin’s 1969 talks with Zhou Enlai). But neither guest succeeded in convincing the Chinese leadership to end their straddling and support his side.

US-Soviet rivalry took a more lethal form in Cambodia. On Christmas Day 1978 Vietnamese forces had invaded Cambodia and set up a puppet communist government, the PRK (People’s Republic of Kampuchea). Although expressing relief over the end of the murderous Khmer Rouge regime, most of the world condemned Hanoi’s violation of its neighbor’s sovereignty and refused to recognize the PRK. Two months later, China launched a brief punitive attack on Vietnam. Moscow, responding to Hanoi’s pleas, had agreed to provide military support in return for the lease of naval and air bases at the former US facilities in Da Nang and Cam Ranh Bay, thus bringing some seven thousand Soviet military personnel into the region.

After more than thirty years of conflict, Cambodia descended into a bloody civil war. Bolstered by some 180,000 Soviet-armed Vietnamese troops (whose presence Hanoi repeatedly denied), the PRK leader Heng Samrin faced three disparate insurgent movements, among them the Chinese-backed Khmer Rouge, which made deep cross-border forays from refugee camps and military bases in Thailand. In 1982, the United States and China put pressure on the communist and noncommunist rebels to form the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea (CGDK) under the presidency of Prince Norodom Sihanouk. Over Soviet protests, the CGDK was seated by the United Nations.

Cambodia’s neighbors played a major role in its civil war. China and Thailand (Vietnam’s historic enemies) were determined to check Hanoi’s efforts to dominate all of Indochina and demanded a full withdrawal of its troops. But the CGDK remained a tense alliance of opposites, with China supporting the Khmer Rouge, Thailand and other ASEAN* members providing economic and military aid to the noncommunist elements, and the United States (swallowing its misgivings over the Khmer Rouge’s involvement) sending substantial aid to the coalition as well.

As in Afghanistan, the struggle over Cambodia represented a high-stakes US-Soviet proxy war. Washington sought to topple a Soviet- and Vietnamese-backed regime, and Moscow, risking US and Chinese ire, paid huge sums to bolster its Vietnamese ally (estimated at some $3 million per day) as the price of acquiring two former US bases, which gave the USSR enhanced intelligence capability and increased its air force’s range in East and Southeast Asia.

Despite the CGDK Coalition’s vast resources and their own growing economic weakness and international isolation, the Vietnamese and their PRK allies held out. Fed by Chinese, US, and Soviet arms, the Cambodian civil war became a grinding stalemate.

The US-Soviet contest also intensified in Southern Africa. The key player here was South Africa, whose regional position had changed dramatically with the attainment of independence by Angola, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe. The Pretoria government saw itself facing a barrage of threats from its Soviet-armed neighbors and opponents: from the three black-ruled front-line states; from the exiled ANC (African National Congress), based in Angola and Mozambique; from SWAPO (Southwest Africa People’s Organization), headquartered in Angola and demanding independence for its longtime trust-colony Namibia; and from the South African Communist Party (SAC). In addition, South Africa faced increased pressure by Western governments to ease white-minority rule, growing diplomatic isolation, and an expanding domestic opposition.

In response, the Nationalist prime minister P. W. Botha in 1979 launched his “total strategy.”* It included strong presidential government at home and a campaign of subversion in Zimbabwe, clandestine air and ground operations in Mozambique and Angola, and continued support of opposition movements in both countries: RENAMO (Resistência Nacional Moçambicana) in Mozambique and UNITA (União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola) in Angola. Botha also refused to relinquish control over Namibia to a Marxist SWAPO regime.

The Reagan administration, which regarded South Africa as a valuable strategic ally and raw-materials provider, was highly receptive to its fears of a Soviet master plan to control all of southern Africa. Reversing Carter’s coolness toward the Pretoria government, Washington revived the policy of constructive engagement, stressing quiet diplomacy to induce reforms by the white-minority government and withholding criticism of its security forces’ use of violence against unarmed protesters. Moreover, Reagan not only countenanced South Africa’s air and ground raids against its neighbors but also demanded the withdrawal of the twenty-five thousand to thirty thousand Cuban troops remaining in Angola. In addition, Washington provided clandestine direct and indirect aid to UNITA, even hailing its leader Jonas Savimbi as a “freedom fighter.”

The Soviet Union, a longtime supporter of armed independence movements in southern Africa, had seemed triumphant in 1980. In response to South Africa’s stepped-up aggression, the Kremlin dispatched some two thousand military advisers to Angola to train government- and ANC-armed forces and increased its shipments of arms to Angola and Mozambique. But in the face of mounting East-West tension, unrest in Eastern Europe, its protracted entanglement in Afghanistan, and a dangerous situation in the Middle East, the Kremlin found itself unable to maintain a leading position in southern Africa. Lacking the military forces and economic resources to bolster its clients, Moscow bleakly watched the leaders of Angola and Mozambique approach Pretoria and the United States in 1984 to secure their future.

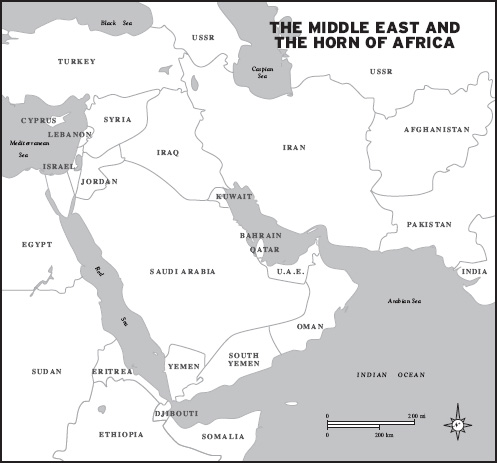

The Superpower competition in the Middle East was shaped by violent clashes in this region, which included the 1980–1988 Iraq-Iran War and the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict as well as the appearance of radical Islamic jihadists (religious warriors) in Afghanistan, Lebanon, and Egypt.* With the demise of détente, nothing remained of Nixon and Brezhnev’s 1972 pledge to refrain from exploiting quarrels in the world’s most volatile region for their own benefit.

On September 22, 1980, Saddam Hussein, who only a year before had seized control of Iraq,† launched an invasion of Iran, pitting a charismatic secular Arab leader against Khomeini’s revolutionary Shi’ite forces. Hussein’s grave miscalculation—that the Arab world would rally to Baghdad’s side and that Iran would quickly collapse—led instead to an eight-year war between two heavily armed old rivals that cost over a million lives and calcified the two repressive political regimes.

According to official records so far available, this was a war neither Superpower had encouraged and both had tried to stay out of.* But shortly after taking office, the Reagan administration reversed Carter’s neutral stance toward the combatants. Washington, seeking to punish Iran’s sponsorship of international terrorism and ignoring Iraq’s human rights abuses, tilted toward Baghdad. In response to Iran’s 1982 counteroffensive, the United States stepped up civilian, technological, and ultimately military aid to Iraq, shared crucial satellite intelligence, and reestablished full diplomatic relations in 1984. The United States also encouraged its allies to provide arms to Iraq and watered down UN resolutions condemning Hussein’s use of chemical weapons.

Moscow’s situation was far more delicate. Concerned over Tehran’s threat to its Islamic border republics and over both sides’ ferocious anticommunist campaigns, the Soviet Union decided to straddle. It tilted first toward Tehran, then declared its neutrality, and then in late 1983 resumed arms sales to Baghdad but also continued sending supplies to Iran and countenancing weapons deliveries to Tehran by its allies Libya, Syria, and North Korea.

More than an appalling sideshow, the Iran-Iraq War underlined the Superpowers’ obsession with checking each other’s influence in the Gulf region, even at the cost of expanding the violence.* Neither side endorsed Hussein’s pan-Arab dream or the collapse of Iran, nor did they wish for an Iranian victory and the dismemberment of Iraq. Yet despite the convergence of Washington and Moscow’s interests, the new chill between the two capitals checked any initiative to bring the warring parties to the peace table until 1987. America’s principal interests, to protect its anticommunist Gulf allies (Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Oman, and Bahrain) and to secure the West’s oil supplies, kept it solidly in the arms game, while the Soviet Union, capitalizing on the world’s distraction from its imbroglio in Afghanistan, succeeded in expanding its influence in the Muslim world. In the meantime, more than thirty countries sent weapons to the belligerents, with China and several others arming both sides.

The next Superpower crisis was precipitated by Israel’s June 6, 1982, invasion of Lebanon, a country that had been engulfed in civil war since 1975, was occupied by thirty thousand Syrian troops, and was also the headquarters of the PLO leadership. Just two months after Israel’s complete evacuation of the Sinai Peninsula (as specified in the 1979 Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty), the Begin government, perceiving Washington’s indecisive signals as a green light,† sent an army into Lebanon to eliminate the Palestinian threat to its northern border. But rather than halting in southern Lebanon—as the United States and the world expected—Israel expanded the campaign. Following air attacks on the PLO headquarters in Beirut and on the Syrian Soviet missile sites in the Bekaa Valley, Israeli ground forces on June 13 reached Beirut, where they hoped to install a friendly government under the Christian Maronite leader Bashir Gemayel.

Israel achieved a major military triumph. It captured large numbers of Palestinian prisoners and their Soviet arms and forced the evacuation of Yasser Arafat, the entire PLO leadership, and some fourteen thousand Palestinian troops to Tunisia under the supervision of a US-led multinational force. But victory quickly turned sour. Large segments of the world public, including Israeli peace groups, condemned the Begin government for inflicting high casualties on Lebanon’s civilian population. In September Israel lost a crucial partner when Gemayel was assassinated on the orders of Syrian intelligence. Even more damaging to Israel were the massacres in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps. On September 16, under its soldiers’ watch, Israel’s Lebanese Christian allies, seeking revenge for Gemayel’s murder, slaughtered some eight hundred Palestinians, creating an international scandal in which Israel was widely blamed for failing to stop the atrocities. Moreover, Israel ultimately failed to dislodge the Syrian forces, and a new organization, Hezbollah (Party of God), backed by Syria and Iran, emerged in Lebanon as a powerful Islamic, anti-Israeli force.

The Reagan administration, aroused by the violence in Lebanon and the public outcry, attempted to take charge. On September 20 Washington announced the formation of a second multinational peacekeeping force and the dispatch of 1,800 marines to Lebanon to bolster the central government. The Kremlin (unlike Khrushchev’s bombastic response to Eisenhower’s 1958 intervention in Lebanon*) issued only a mild protest. But the installation of a US-dominated force in Lebanon immediately raised opposition from the antigovernment Muslim militias, which accused Washington of supporting Israel and the Christians.

Although characterizing the US intervention in Lebanon as part of the East-West global conflict, neither Reagan nor Secretary of State Shultz was prepared to engage vigorously in the problems of the Middle East. Because of this US leadership gap, Israel and Syria’s positions hardened, the Palestinian problem remained unresolved, and the sectarian violence escalated in Lebanon. The year 1983 also saw a wave of suicide attacks against American targets, beginning with the April assault on the US embassy in Beirut that claimed 63 lives, including 17 American citizens, and culminating in the October bombing of the Beirut marine barracks in which 241 US servicemen were killed. In response to this deadliest assault on US forces abroad since World War II, the White House ordered no military retaliation but faced congressional pressure to pull out. Reagan, now preparing his reelection campaign, in February 1984 ordered the departure of all US troops by April. It was a humiliating US withdrawal.

The Kremlin was also shaken by the Lebanon conflict. It had gambled on sitting on the sidelines in order to avoid a confrontation with the United States and inciting even stronger Israeli military action. Stung by radical Arab criticisms of its inferior weaponry, its failure to support the PLO and the Syrians, and its brutal war in Afghanistan, Moscow responded to Washington’s intervention by greatly expanding its military commitment to Syria. This included the delivery of more than $2 billion in new sophisticated weaponry and aircraft, along with the first long-range SA-5 missile batteries outside the Warsaw Pact countries, which were operated by 1,500 Soviet military personnel.

More than any other site of Superpower controversy, the Middle East defied a bipolar structure. In this region of colonial-drawn borders and rival religions and ethnic groups as well as crucial oil supplies, neither Washington nor Moscow controlled its clients, but both were still trapped by their Cold War reflexes to seek advantage wherever possible. It was nonetheless an unequal competition. Although neither side understood the rising anti-Western sentiments in the region, America exerted a stronger attraction to all sides because of its greater economic and military power.

Cold War rhetoric continued to reverberate in Washington. Following his overwhelming reelection victory, Reagan in his January 21, 1985, inaugural address vowed to seek an agreement with Moscow over nuclear weapons but also reaffirmed his commitment to SDI, insisted that the United States must remain militarily strong, and declared that “human freedom is on the march and nowhere more so than our own hemisphere.”

But in Moscow a shift was taking place. On March 11, the politburo unanimously selected as the successor to Chernenko its youngest member, Mikhail Gorbachev. Three months earlier, the new general secretary of the Soviet Union had already signaled a change in Moscow’s direction by pronouncing the Cold War an “abnormal” condition of international relations and calling for “new political thinking” (novoe politicheskoe myshlenie) to combat the menace of nuclear war.

Documents

Morozov, Boris. Documents on Soviet Jewish Emigration. London: Frank Cass, 1999.

Reagan, Ronald. “Foreword Written for a Report on the Strategic Defense Initiative, December 28, 1984.” The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=38499&st=strategic+defense+initiative&st1.

———. “Remarks at the Annual Convention of the National Association of Evangelicals in Orlando, Florida.” Evil Empire Speech, March 8, 1983. Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Library. http://www.reaganfoundation.org/bw_detail.aspx?p=LMB4YGHF2&h1=0&h2=0&sw=&lm=berlinwall&args_a=cms&args_b=74&argsb=N&tx=1770.

“Shaking Hands with Saddam Hussein: The US Tilts Toward Iraq, 1980–1984.” National Security Archive. 2003. http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB82/index.htm.

“Solidarity and Martial Law in Poland: 25 Years Later.” National Security Archive. 2006. http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB211/index.htm#docs.

Contemporary Writing

Friedman, Thomas L. From Beirut to Jerusalem. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1989.

Havel, Václav. The Power of the Powerless: Citizens Against the State in Central-Eastern Europe. Edited by John Keane. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 1985.

Hersh, Seymour M. “The Target Is Destroyed”: What Really Happened to Flight 007 and What America Knew About It. New York: Random House, 1986.

Konrád, György. Antipolitics: An Essay. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1984.

Michnik, Adam. Letters from Prison and Other Essays. Translated by Maya Latynski. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985.

Talbott, Strobe. Deadly Gambits: The Reagan Administration and the Stalemate in Nuclear Arms Control. New York: Knopf, 1984.

Memoirs and Diaries

Banī ![]() adr, Abū al-

adr, Abū al-![]() asan. My Turn to Speak: Iran, the Revolution and Secret Deals with the U.S. Washington, DC: Brassey’s, 1991.

asan. My Turn to Speak: Iran, the Revolution and Secret Deals with the U.S. Washington, DC: Brassey’s, 1991.

Gates, Robert Michael. From the Shadows: The Ultimate Insider’s Story of Five Presidents and How They Won the Cold War. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996.

Reagan, Ronald. An American Life. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990.

———. The Reagan Diaries. Edited by Douglas Brinkley. New York: Harper Collins, 2007.

Shultz, George Pratt. Turmoil and Triumph: My Years as Secretary of State. New York: Scribner’s, 1993.

Weinberger, Caspar W. Fighting for Peace: Seven Critical Years in the Pentagon. New York: Warner Books, 1990.

Alsino and the Condor. Directed by Miguel Littin. Havana: Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industrias Cinematográficos, 1983.

The Day After. Directed by Nicholas Meyer. Los Angeles: ABC Circle Films, 1983.

Heartbreak Ridge. Directed by Clint Eastwood. Los Angeles: Jay Weston Productions, 1986.

The Hunt for Red October. Directed by John McTiernan. Los Angeles: Paramount Pictures, 1990.

The Iron Lady. Directed by Phyllida Lloyd. London: Pathé, 2011.

Lebanon. Directed by Samuel Maoz. Tel Aviv: Ariel Films, 2009.

Man of Iron. Directed by Andrzej Wajda. Łódź: Film Polski, 1981.

No End. Directed by Krzysztof Kieślowski. Łódź: Film Polski, 1985.

Pictures from a Revolution. Directed by Alfred Guzzetti, Susan Meiselas, and Richard P. Rogers. New York: GMR Films, 1991.

Red Dawn. Directed by John Milius. Los Angeles: United Artists, 1984.

Repentance. Directed by Tengiz Abuladze. Tbilisi, Georgia: Qartuli Pilmi, 1984.

Threads. Directed by Mick Jackson. London: BBC, 1984.

Waltz with Bashir. Directed by Ari Folman. Jaffa: Bridgit Folman Film Gang, 2008.

World War III. Directed by David Greene and Boris Sagal. Los Angeles: NBC, 1982.

Fiction

Brinkley, Joel. The Circus Master’s Mission. New York: Random House, 1989.

Jabrā, Jabrā Ibrāhīm. In Search of Walid Masoud: A Novel. Translated by Roger Allen, and Adnan Haydar. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2000.

Khūrī, Ilyās, and Humphrey T. Davies. Gate of the Sun. Brooklyn: Archipelago Books, 2005.

Paton, Alan. Ah, but Your Land Is Beautiful. New York: Scribner, 1982.

Sammān, Ghaādah. Beirut Nightmares. London: Quartet Books, 1997.

Children’s Literature

Dr. Seuss [Theodore Geisel]. The Butter Battle Book. New York: Random House, 1984.

Secondary Sources

Alekseeva, Ludmila. Soviet Dissent: Contemporary Movements for National, Religious, and Human Rights. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1985.

Barber, James P., and John Barratt. South Africa’s Foreign Policy: The Search for Status and Security, 1945–1988. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Ben-Zvi, Abraham. The United States and Israel: The Limits of the Special Relationship. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993.

Blight, James G. Becoming Enemies: U.S.-Iran Relations and the Iran-Iraq War, 1979–1988. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2012.

Cannon, Lou. President Reagan: The Role of a Lifetime. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1991.

Dannreuther, Roland. The Soviet Union and the PLO. New York: St. Martin’s, 1998.

Diggins, John P. Ronald Reagan: Fate, Freedom, and the Making of History. New York: Norton, 2007.

Evron, Yair. War and Intervention in Lebanon: The Israeli-Syrian Deterrence Dialogue. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987.

Freedman, Robert Owen. Moscow and the Middle East: Soviet Policy Since the Invasion of Afghanistan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Halverson, Thomas E. The Last Great Nuclear Debate: NATO and Short-Range Nuclear Weapons in the 1980s. Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan, 1995.

Herf, Jeffrey. War by Other Means: Soviet Power, West German Resistance, and the Battle of the Euromissiles. New York: Free Press, 1991.

Jaster, Robert S. South Africa in Namibia: The Botha Strategy. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1985.

Laïdi, Zaki. The Superpowers and Africa: The Constraints of a Rivalry, 1960–1990. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

Lawson, Fred Haley. Why Syria Goes to War: Thirty Years of Confrontation. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996.

Lynch, Edward A. The Cold War’s Last Battlefield: Reagan, the Soviets, and Central America. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2011.

Medvedev, Zhores A. Andropov. New York: Norton, 1983.

Monaghan, David. The Falklands War: Myth and Countermyth. Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan, 1998.

Richardson, Sophie. China, Cambodia, and the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence. New York: Columbia University Press, 2010.

Schweizer, Peter. Victory: The Reagan Administration’s Secret Strategy that Hastened the Collapse of the Soviet Union. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1994.

Scott, James M. Deciding to Intervene: The Reagan Doctrine and American Foreign Policy. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1996.

Sjursen, Helene. The United States, Western Europe and the Polish Crisis: International Relations in the Second Cold War. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

Smith, Geoffrey. Reagan and Thatcher. New York: Norton, 1991.

Taylor, Alan R. The Superpowers and the Middle East. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1991.

Vogel, Ezra F. Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2011.

Wittner, Lawrence S. Toward Nuclear Abolition: A History of the World Nuclear Disarmament Movement, 1971 to the Present. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2003.

Young, Marilyn J., and Michael K. Launer. Flights of Fancy, Flight of Doom: KAL 007 and Soviet-American Rhetoric. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1988.

![]()

* US annual military spending rose from approximately $155 billion in 1980 to almost $300 billion in 1986.

† Two spectacular manifestations were the 1980 Krefeld Appeal in West Germany against US missiles, signed by 2.7 million people, and the 1981–1983 women-led siege of the Royal Air Force base at Greenham Common in Britain to block their installation.

‡ A label originally applied to the Hungarian rebels in 1956.

* The only professional soldier to lead a European communist country, Jaruzelski first served as premier and first secretary of the Communist Party and, after 1985, as the country’s president.

† According to 1981 KGB reports, there were also mass strikes in the Baltic republics, Belarus, and western Ukraine, causing Soviet authorities to close the borders with Poland.

* On May 4, 1983, the US House of Representatives had voted 278–149 in support of a freeze.

* In 1996, Gennadiy Osipovich, the Soviet pilot who downed the Korean aircraft, admitted to the New York Times that he had recognized the civilian airliner but, following his chief’s orders and believing it was on a spying mission, had nonetheless fired.

* Phrase used on November 7, 1983, by politburo member Gregory Romanov to characterize the international climate.

† Among the remaining mysteries is KAL 007’s twelve-minute-long descent after the firing of the missiles and the fact that practically no human remains or luggage and little debris were found, feeding CIA theories of either a ditching at sea or a landing on Sakhalin and subsequent Soviet captivity, neither of which have ever been proven.

* The Able Archer exercises, which were conducted between November 2 and 11 at a moment of heightened Superpower tensions for the purpose of testing new codes, involving NATO heads of government and simulating a period of conflict escalation that would culminate in the release of a nuclear weapon, convinced some nervous Soviet officials of the imminence of a genuine attack and resulted in the placing of Soviet air units in Poland and East Germany on alert.

† It was later seen by hundreds of millions of people in forty countries.

* Toward the end of this gathering, which took place over three years, between 1980 and 1983, there was a heated US-Soviet debate over the implementation of the Helsinki human rights provisions.

† Following the chill in US-Soviet relations after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the numbers of Jewish emigrants dropped from a high of 51,320 in 1979 to 21,471 in 1980; 9,447 in 1981; 2,688 in 1982; 1,315 in 1983; and only 896 in 1984.

* In 1984 Nicaragua brought a complaint against the United States to the International Court of Justice at The Hague for numerous violations of its sovereignty, including the mining of its harbors. The court, rejecting US insistence that its jurisdiction did not apply to matters relating to Central America, ruled against Washington, which then blocked enforcement by the Security Council. In 1992, after the Sandinista government was replaced through the electoral process, Nicaragua withdrew the complaint.

† In April 1965 Lyndon Johnson, fearing the creation of a “second Cuba,” had ordered the invasion of the Dominican Republic, resulting in a pro-US government.

* Called the Malvinas by Argentina (and most Latin American and European countries), the Falklands, lying 290 miles east of the Argentinean coast and 8,000 miles southwest of the British Isles, had been under British control since 1833, which had been contested by the Argentineans ever since.

† On April 2, 1982, the Argentinean military junta, angered over five years of futile negotiations with the British and attempting to divert public attention from the debt crisis, which had brought inflation and high unemployment, and from its human rights abuses ordered an invasion of the islands. A shocked Thatcher government, aiming to reverse its sagging popularity over Britain’s economic troubles, demanded a complete withdrawal, refused US offers to mediate, and launched a naval force to retake the islands, which was completed on June 14. After the debacle, the junta was forced to resign, and Margaret Thatcher’s popularity soared.

‡ One of the world’s oldest regional organizations (originally founded in 1889 and established in its new structure in 1948), the OAS is a thirty-five-member institution, headquartered in Washington, DC, whose purpose is to promote security and solidarity in the Americas.

* The one exception was Chinese-American collaboration in arming the mujahideen in Afghanistan, in which the United States purchased Soviet-designed arms produced in China and transmitted them through Pakistan.

* The Association of Southeastern Asian Nations was an anticommunist organization founded in 1967 by Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand and endorsed by the United States, Canada, Britain, and Australia.

* In 1977, Botha, as defense minister, had begun South Africa’s nuclear weapons program.

* Manifested dramatically in the 1981 assassination of Egyptian president Anwar Sadat by members of the Muslim Brotherhood.

† After being named president, army commander in chief, head of government, and secretary-general of its ruling Ba’ath Party in the summer of 1979, Hussein instigated a bloody purge of his political rivals, created a powerful security network, and suppressed Shi’ites, Kurds, and other potential dissident groups.

* One year before the invasion, the United States learned of Saddam Hussein’s intentions and passed on word to Iran, but neither the Carter administration nor the Kremlin gave Iraq a green light to invade.

* That included the world’s first attacks on a nuclear facility: Iran’s unsuccessful bombing of Iraq’s Osirak reactor in September 1980, followed by the Israeli strike in June 1981, which destroyed it and brought unanimous condemnation by the UN Security Council.

† Despite State and Defense Department concerns over damaging US-Arab relations, Secretary of State Alexander Haig had voiced no opposition to the invasion.

* When the president, answering the Beirut government’s appeal, had sent fourteen thousand troops to Lebanon to thwart a Nasserite coup and form a new pro-Western government.