THE END OF THE COLD WAR, 1985–1991

I really do inhabit a system in which words are capable of shaking the entire structure of government, where words can prove mightier than ten military divisions.

—Václav Havel

Nothing will ever be the same as it was.

—Willy Brandt

In his 1987 book, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, the Yale historian Paul Kennedy surveyed five centuries of imperial overstretch. Significantly, the concluding chapters focused primarily on the United States, which, Kennedy believed, was slipping from its place as the world’s Number One. This was due not only to economic competition from Europe, Japan, and China but primarily to the escalating cost of America’s Cold War defense establishment, which had raised the national debt in 1985 to the stratospheric figure of $1.8 trillion.

However, by the winter of 1986, many observers drew an even bleaker picture of the USSR. Drained by the war in Afghanistan and by subsidies to its satellites and overseas clients; jarred by the precipitous drop in world oil and gas prices, the fall in its foreign currency earnings from trade, and declining agricultural and industrial production; crippled by its technological backwardness and rigid bureaucracy (which that year were underscored by the Chernobyl disaster); and fending off increasingly restive national minorities, the Soviet Union seemed to be facing an existential crisis.

Yet no one in 1985 expected the peaceful end of US-Soviet rivalry, the fall of the communist regimes in Eastern Europe, the reunification of Germany, and the demise of the Soviet Union—all of which occurred in the next six years. These unforeseen developments have created a lively historical debate over how and why they occurred and when the Cold War actually ended.

THE GORBACHEV REVOLUTION IN INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS

After his arrival in Moscow from Stavropol in 1978, Mikhail Gorbachev quickly became one of the politburo’s most active members and caught the eye of Andropov as a fellow reformer and likely successor. In nominating him to succeed the Brezhnev-loyalist Chernenko, Gromyko praised the new leader’s “unquenchable energy” and commitment to “put the interests of the Party, society, and people before his own.” Young, well-educated, and articulate, and backed by the party and military chiefs, Gorbachev accepted a mandate in March 1985 to reform and strengthen the Soviet Union and to “realize our shining future.”

Nevertheless, during his first two years Gorbachev’s domestic policies were erratic and largely ineffective. Without challenging the centerpiece of the Soviet regime—the planned economy—or its outsized military budget, the new general secretary and his political allies launched the politically damaging anticorruption and anti-alcoholism campaigns and also made futile attempts to boost industrial production and labor discipline. On February 25, 1986, thirty years after Khrushchev had exposed Stalin’s misdeeds, Gorbachev promoted his perestroika (reconstruction) policy before the Twenty-Seventh Party Congress. Unlike the mix of reforms occurring concurrently in China that allowed decentralization and focused on agriculture and light industry as the motors of modernization, Gorbachev’s was a top-down centralized program emphasizing heavy industry and maintaining many of the macroeconomic aspects of the Stalinist command system. It failed to alleviate the bottlenecks and shortages in the Soviet economy.

Gorbachev’s political views were more audacious. Unlike Deng Xiaoping, who, after the chaos of the Cultural Revolution, was obsessed with stability and ruled out democratic reforms, Gorbachev linked perestroika with a policy of glasnost (openness). Taking aim at the USSR’s encrusted party and bureaucracy, Gorbachev adopted a stillborn project of Andropov’s to reduce their power by introducing new—even Western—ideas into the Soviet environment and engaging the Soviet population in modernizing the country. He went so far as to authorize the opening of the records of Soviet history, including its darkest moments, which ignited an explosion of criticism reaching back to Lenin’s rule. To be sure, Gorbachev’s purpose was to preserve the communist system by revitalizing it from above, but by combining perestroika with glasnost the Soviet leader risked unleashing forces he was ultimately unable to control.

Gorbachev was even more daring in his foreign policy, because he believed that the relaxation of international tensions was indispensable to his political reforms at home. Convinced that the Soviet Union’s greatest threat was nuclear war but that its huge military budget was unsupportable, he intended to achieve security by scaling down the global rivalry between Moscow and Washington and reviving détente. After assembling a group of like-minded liberal internationalists, among them the new foreign minister, Eduard Shevardnadze, and his foreign policy adviser, Anatoly Chernyaev, Gorbachev boldly embarked on a step-by-step program of reducing the USSR’s isolation and reaching out to the other side, which included Western Europe, Japan, and China as well as the United States. Yet there would be no precipitate surrender of strategic interests. In 1985 Moscow increased its military operations in Afghanistan and its flow of aid to Cuba, Nicaragua, Vietnam, Ethiopia, and Syria.

Gorbachev faced a wary Western audience, which he hoped to woo with vows to end the arms race. Before taking office, during his December 1984 visit to Britain, he had referred to Europe as “a common home . . . and not a theater of military operations” and had convinced Thatcher that he was a man with whom the West could “do business.” But the Reagan administration, facing unexpectedly strong congressional opposition to its military budget, was unreceptive to the new leader’s message and intensified its charges of the Soviets’ untrustworthiness and deplorable human rights record. Nonetheless, in a private message Reagan expressed interest in a summit meeting and assured Gorbachev of his hope to resume the search for “mutual understanding and peaceful development.”

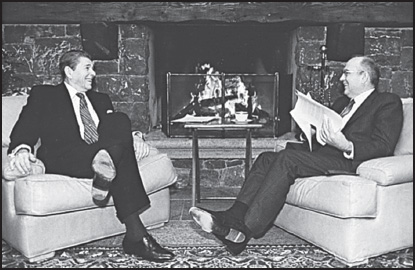

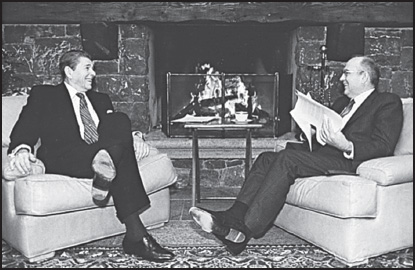

The US and Soviet leaders met in Geneva in November 1985. At this first Superpower summit in six years, no treaty was signed, but the two-day meeting gave Reagan and Gorbachev an opportunity to evaluate each other and air their differences. Although they jointly declared that “a nuclear war can never be won and must never be fought” and agreed to accelerate work on arms control, Reagan defended SDI, and Gorbachev refused to expand the agenda to include Afghanistan and human rights.

The rift continued to widen in 1986. Seeking to draw the world’s support for his peace offensive (signaled by a unilateral moratorium on Soviet nuclear tests and his appeals to revive START, the stalled Strategic Arms Reduction Talks), Gorbachev boldly called for complete nuclear disarmament by the year 2000 and, reversing four decades of Soviet resistance, expressed his willingness to accept on-site inspections.

The Reagan administration continued to rebuff what it termed Moscow’s “propaganda ploy,” deriding Gorbachev’s campaign against SDI and dismissing his proposal for extensive reductions in conventional military forces in Europe as a tactic to divide NATO. Washington underlined its forceful stance by announcing a new series of atomic tests, stepping up anti-Soviet actions in Afghanistan, launching several highly provocative intelligence-gathering activities, arming its B-52 bombers with air-launched cruise missiles,* and conducting air strikes against Moscow’s ally Libya, which it accused of sponsoring global terrorism. US-Soviet relations were also frozen in 1986 because of two sensational spy scandals.†

But Gorbachev’s persistence led to a second summit in Reykjavik on October 11–12, 1986, one of the most astonishing encounters of the entire Cold War. On day 1, Gorbachev startled the Americans by proposing a 50 percent reduction in all strategic weapons, eliminating all intermediate-range missiles in Europe, extending the ABM treaty for at least ten years, and reopening the stalled talks on a comprehensive nuclear test-ban treaty. After the Americans presented their response on the second day—the elimination of all strategic missiles everywhere in the next decade—Gorbachev countered by proposing the abolition of all nuclear weapons. Reagan, sensing a unique opportunity to stop the threat of nuclear wars, readily agreed. Much to the chagrin of their advisers and allies, the two leaders suddenly agreed to halve their atomic arsenals by 1991 and to eliminate them entirely by 1996.

But no deal was cut at Reykjavik because of their differences over SDI, which, regardless of its impracticability, had immense symbolic importance to both leaders. Gorbachev had linked his substantial concessions with a demand that the program be confined to the laboratory, and Reagan refused. After the summit’s disappointing end, each used bitter words to blame the other, and a chill descended on US-Soviet relations. Their public setback, emphasized by the media, was all the more painful because both leaders also suffered major reversals at home: Reagan over the Democrats’ capture of both houses of Congress and the eruption of the Iran-Contra scandal,* and Gorbachev over the swelling death toll from the explosion at the Soviet nuclear plant in Chernobyl, the mounting casualties in Afghanistan, the plummeting of oil and gas revenues, and the Soviet Union’s economic meltdown and ballooning national deficit.

Refusing to abandon his peace offensive, Gorbachev produced more surprises. Intent on rehabilitating the Soviet Union’s reputation before world public opinion, he initiated major breakthroughs in human rights, beginning with the February 1986 freeing of the famed Jewish political prisoner Natan Sharansky. On December 19, 1986, Gorbachev personally phoned the dissident Andrei Sakharov to inform him of his release from his Gorki exile. One month later the Soviets ceased jamming the BBC, the Voice of America, and Germany’s Deutsche Welle broadcasts and lifted censorship of banned books, such as Boris Pasternak’s Dr. Zhivago. The KGB reduced the number of arrests for political crimes, and the government released almost all political dissidents and allowed greater religious freedom and freedom of expression. In 1987 the number of Jews granted exit visas rose to almost eight thousand from fewer than one thousand the year before.

Still, Reagan was skeptical over the Soviet leader and hammered away at the evil empire. On his June 1987 visit to celebrate Berlin’s 750th anniversary, the president, standing in front of the Brandenburg Gate, urged Gorbachev to “tear down this wall” that surrounded West Berlin.*

Both leaders continued to express support for arms control, but it was Gorbachev, by suspending his objections to SDI and removing strategic-weapon reductions from the negotiations, who made a breakthrough treaty on intermediate-range nuclear forces (INF) possible. In 1981 Reagan had overridden NATO’s Dual-Track initiative† by proposing the “zero option” (removing all missiles from Europe), which Moscow, predictably, had refused. The talks, suspended by Andropov in 1983, now resumed.

Following months of difficult negotiations, the United States and the USSR concluded a path-breaking agreement to destroy all short- and intermediate-range ground-based nuclear missiles in Europe by 1991. Conceding what Andropov had rejected, Gorbachev also agreed to retire the SS-20 missiles from sites in Soviet Asia. This first strategic arms agreement between the Superpowers for almost a decade was unprecedented, calling for the removal of an entire class of nuclear weapons and establishing elaborate verification measures.

Gorbachev’s reward was his celebrated trip to the United States in December 1987. Fourteen years after Brezhnev’s visit, Gorbachev’s American journey was a brilliant performance, during which he mingled with Washington crowds and signed the INF treaty on December 8 in a White House brimming with warmth. Yet the Cold War had not ended. The INF treaty eliminated only 4 percent of the Superpowers’ nuclear warheads, and long months of acrimonious discussion lay ahead.

Gorbachev then took major steps to end the Soviet Union’s military and economic activities abroad. In February 1988 he announced the phased withdrawal of all Soviet troops from Afghanistan, to be completed in two years.* That year Moscow prodded Hanoi to remove its troops from Cambodia, thus ending another major conflict with Washington and Beijing. Also, the Soviet Union reduced its aid to the allied governments in Vietnam, Angola, and Ethiopia and prepared to evacuate Cam Ranh Bay.

Reagan now responded. With only six months remaining in his presidency (and still under the cloud of the Iran-Contra scandal), the US president made his first—and extraordinarily memorable—visit to Moscow. With no treaties to sign, it was nonetheless a gala event, with the Soviet capital lavishly adorned to greet its seventy-seven-year-old former adversary. Reagan met with human rights activists. Standing before a giant Lenin statute, he addressed students at Moscow State University, calling for “freedom [to] blossom forth at last in the rich fertile soil of your people and culture” and for “a new world of reconciliation, friendship, and peace.” He also strolled with Gorbachev in Red Square and recanted his evil empire charge. Yet despite all the signs of geniality, Reagan underscored the power imbalance by refusing to issue a joint statement that echoed the Kremlin’s old creed: “Equality of all states, noninterference in internal affairs, and freedom of sociopolitical choice [are] inalienable and mandatory standards of international relations.”

Gorbachev’s most impressive moment was still to come. On December 7, 1988, in his address to the UN General Assembly he declared the end of the Cold War, renouncing not only the 1945 Yalta settlement† but also the ideological struggle between the Soviet Union and the West since November 1917. According to the Soviet leader, the Bolshevik Revolution had entered the realm of history, and class conflict would no longer dominate global politics. “We are entering an era in which progress will be based on the common interests of the whole of mankind. . . . The common values of humanity must be the determining priority in international politics [requiring] the freeing of international relations from ideology.”

Gorbachev also repudiated the Brezhnev doctrine: “Force or the threat of force neither can nor should be instruments of foreign policy. . . . To deny a nation of freedom of choice, regardless of the pretext or the verbal guise in which it is cloaked, is to upset the unstable balance that has been achieved. . . . Freedom of choice is a universal principle, which knows no exception.”

Gorbachev’s third point was to pronounce a new reality in the arms race: given the unlikelihood of a Superpower conflict, the principle of stockpiling arms was to be replaced with one of “reasonable sufficiency.” To make this clear, he announced a unilateral cut of five hundred thousand men from the Soviet army and a withdrawal of fifty thousand soldiers and five thousand tanks from the Soviet forces in Eastern Europe, and he proposed negotiations on even greater reductions. One day later, during his private New York meeting with the outgoing Reagan and the new US president George H. W. Bush, Gorbachev pressed for rapid progress in arms control leading to the complete abolition of nuclear weapons.

Thus within three years the former Andropov protégé had totally transformed Soviet foreign policy, replacing its messianic Marxist creed with a radical internationalism. Among the strongest reactions was in the New York Times, whose December 8 editorial stated: “Perhaps not since Woodrow Wilson presented his Fourteen Points in 1918 or since Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill promulgated the Atlantic Charter in 1941 has a world figure demonstrated the vision Mikhail Gorbachev displayed yesterday at the United Nations.”

A number of scholars believe that the Cold War ended in December 1988 with neither a winner nor a loser.* According to this view, one of the Superpowers simply called off the ideological rivalry that began in 1917, withdrew from the post-1945 arms race, and relinquished control over regimes dependent on Soviet force and economic subsidies for their survival. Although not everyone agrees, it is certainly reasonable to assert that without Gorbachev’s bold international agenda the world may well have remained divided into two armed camps, and the events that followed would have had entirely different outcomes.

1989: THE TRANSFORMATION OF EASTERN EUROPE

Although the year 1989 marked the two hundredth anniversary of the French Revolution, there was little radical spirit in either Europe or the rest of the world. The excesses of Lenin and Stalin, Mao Zedong and Pol Pot as well as of the Khomeini regime had discredited the mass uprising as a means of achieving political and social justice. The twentieth century’s major revolutions, co-opted by ruthless revolutionary cliques, had led to terror, dictatorship, and the human nightmare recounted by Solzhenitsyn and many others.

Left-wing ideology had also been weakened in the 1980s by the revival of neoliberal political and economic regimes in the West, by the spectacular success of capitalist experiments in the developing world (particularly in Asia), and also by Gorbachev’s attempt to reform communism. Filling the ideological gap left by orthodox Marxism were two old and powerful forces. One was religion, represented by the militant Islam of Iran but also by the forceful Christian doctrine of Pope John Paul II, the charismatic Polish leader who visited 129 countries during his pontificate championing anticommunism and human rights. The second was nationalism, long suppressed by communists, which the peoples of the Soviet Republics and of Eastern Europe now viewed as an agent of progressive historical development. In the 1980s even the orthodox East German leadership, in an effort to win popular support, honored Martin Luther, Frederick the Great, and the socialists’ old nemesis Otto von Bismarck as national heroes.

Yet there was scant indication that 1989 would witness a stunning transformation in the very site where the Cold War began. On January 15 thousands gathered peacefully in Prague, Czechoslovakia, to mark the twentieth anniversary of the student Jan Palach’s self-immolation in protest against the Soviet invasion, some shouting “Gorbachev” to rebuke the Czech leadership’s refusal to institute reforms. Nervous party leaders ordered a brutal police crackdown using riot sticks, dogs, and water cannon, and almost nine hundred protesters were arrested.* Although outgoing Secretary of State George Shultz denounced this violation of the Helsinki Accords, the incoming Bush administration was unprepared to challenge Soviet control over Eastern Europe.

Nonetheless, the communist regimes in Eastern Europe had become exceedingly fragile. Their economies were in ruins, burdened by huge debts to the West, rising prices, and stagnant wages. Their leadership was dispirited and lacking ideological fervor, the opposition was becoming more defiant, and the media were becoming less restrained in its criticisms. Moscow weighed in by reaffirming its renunciation of the Brezhnev doctrine. In March, Kremlin spokesman Gennadii Gerasimov reaffirmed that each nation “had the right to decide its own fate.”†

Gorbachev’s vow before the United Nations was backed by his actions toward two of the Kremlin’s most rebellious satellites: Poland and Hungary. In Poland, where, despite Jaruzelski’s attempts to imitate perestroika, the economy continued to deteriorate, Moscow approved the roundtable negotiations with Solidarność leaders that in April 1989 led to the legalization of the labor union and national elections and in August to a coalition government led by the Solidarność candidate Tadeusz Mazowiecki. In Hungary, where the 1956 Soviet-installed party chief János Kádár had been toppled in May 1988, the new communist leader Károly Grósz, with the Kremlin’s blessing, instituted radical constitutional changes, scheduled free national elections (including a multiparty system), and on May 2, 1989, opened the barbed-wire fences separating his country from Austria.

The negotiated, top-down changes in Poland and Hungary had been encouraged by the Kremlin, but the grassroots protests that erupted that spring in China created a powerful challenge for both Beijing and Moscow. The Chinese government, enjoying heightened prosperity and international standing in 1989, had prepared to welcome Gorbachev’s visit on May 15 to seal the Sino-Soviet rapprochement resulting from Moscow’s dramatic withdrawals a year earlier. But during his stay in China Gorbachev and the world press also witnessed the gathering in Tiananmen Square of hundreds of thousands of peaceful demonstrators demanding greater democracy and sparking a movement that spread throughout the country. Two weeks after the Soviet leader’s departure, on the night of June 3–4 the government ordered a military crackdown in Tiananmen Square that left some 1,300 dead, tens of thousands wounded, and uncounted numbers imprisoned.

Almost the entire Soviet bloc was aghast at the violence in China; only East Germany’s hard-line leaders applauded Deng Xiaoping’s “victory over counterrevolution.” Gorbachev, although stunned by the bloodshed, was not ready to sever his new ties with Beijing, but he also cautioned his East European comrades to show more “flexibility” toward their populations. Before the Council of Europe on June 6 Gorbachev publicly distanced himself from the Chinese actions, ruling out the threat or the use of force and reasserting the USSR’s ties with our “common European home.”

A populist revolt was also brewing in the German Democratic Republic. Despite its relatively high standard of living, East Germany had spawned considerable discontent against the police state ruled by party chief Erich Honecker, controlled by the infamous Stasi,* and walled in from its richer and freer compatriots in the Federal Republic, which its citizens could view nightly on un-jammable television broadcasts. After Hungary opened its borders, thousands of GDR citizens poured into that country intent on escaping to the West. When blocked from doing so, they went to Czechoslovakia and overwhelmed the West German embassy in Prague, insisting they would remain until allowed to leave for the FRG. But even while arrangements were being made between the two Germanys for their emigration, other GDR citizens demanded a total renovation of East German society and took to the streets chanting, “We are the people,” and “We are staying here.” As demonstrations spread throughout the country, the GDR leadership contemplated a Tiananmen solution.

On his arrival in East Berlin on October 6 for the commemoration of East Germany’s fortieth anniversary, Gorbachev found a regime stunned by the exodus of tens of thousands of its young, educated citizens and by huge crowds calling for democracy. Standing next to Honecker on the reviewing stand before a torchlit parade of party youth, Gorbachev heard the East Germans’ appeal for his help in bringing them freedom. The next day he urged his hosts to heed the people’s needs “before it was too late,” insisting that “dangers await only those who do not react to life.” Significantly, he also ordered the half million Soviet troops in East Germany to remain in their barracks and give no support to the GDR’s attempts to suppress the opposition.

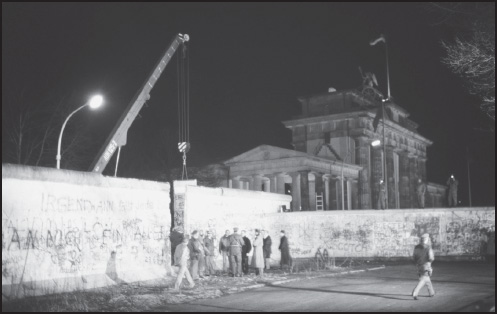

The GDR leadership, attempting to stanch the refugee flood and defuse the protests but shrinking from a military solution, engineered a change from above, replacing the ailing Honecker on October 18 with his protégé, Egon Krenz. The new leader, after journeying to Moscow on November 1 for instructions, announced major reforms of the party and government.* But it was too late. When the refugees and crowds kept growing, the GDR leadership plunged headlong into the abyss. On November 9, Krenz announced that East Germany was lifting most travel restrictions to the West. That night a confused party spokesman assured the press that this policy would be implemented “at once,” forgetting to mention that passports and visas would be required. On hearing this news, masses of people thronged to the transit points of the Berlin Wall, forcing the guards to open the gates, and flooded into West Berlin, where they were received with champagne and flowers. Within hours, the world watched Berliners standing on and dismantling the Cold War’s foremost symbol, the barrier that had divided Germany for twenty-eight years.

The fall of the Berlin Wall took Moscow by surprise. The throng’s spontaneous move westward on November 9, 1989, abruptly ended Gorbachev’s hope for a gradual reconciliation between Europe’s East and West: the East was not only shedding its communist overlords but also disintegrating as a bloc, each nation “hurling itself through the Berlin Wall” toward the West. The carefully crafted compromises achieved in Poland and Hungary quickly collapsed, and the communists fled; even loyalist Bulgaria on November 9 dismissed its long-standing leader, Todor Zhivkov, and announced free elections.

In Czechoslovakia, there was the mostly peaceful “Velvet Revolution.” The hard-line president Gustáv Husák had attempted to use force to put down the protests, but when the demonstrators refused to disperse and Moscow refused a military solution, the regime crumbled. On December 29, after Husák resigned, the playwright and dissident leader Václav Havel, who had spent five years in and out of communist prisons, became president of Czechoslovakia.

Only Romania experienced widespread violence. The communist leader Nicolae Ceauşescu, who had ruled with an iron hand since 1965 and resisted all of Gorbachev’s pleas for reform, was determined to crush the opposition. On December 22, after his troops refused to fire on the crowd, the dictator and his wife fled the capital but were captured, tried, and sentenced to death by a firing squad three days later.

All in all some 110 million people in six countries were affected by the unexpected events of 1989.* During the next year the peoples of Eastern Europe held their first free multiparty elections in four and a half decades and, with the exception of Romania, replaced communists with democrats, including recently imprisoned dissidents. They gradually instituted free markets and eventually withdrew from Comecon, the communists’ trading bloc, and also from the Warsaw Pact. They opened their archives, honoring the victims of the Soviet interventions in 1953, 1956, and 1968; rehabilitating those who had suffered government persecution and violence; and naming (and in some cases punishing) communist informers and torturers. Gorbachev, in a gesture of giant symbolic importance, in 1990 acknowledged Soviet guilt for the massacre of thousands of Polish prisoners in 1940.

Without minimizing the courage and tenacity of the opposition forces, it is fair to say that the transformation of Eastern Europe was unthinkable without Mikhail Gorbachev, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1990. The Soviet leader had not only inspired the reformers but also shaken up their rulers with his withdrawal from Afghanistan, his refusal to prop them up economically, and his announced troop withdrawals in Europe. By embracing new thinking, which stressed mutual security, interdependence, and a common European home, and making good his pledges before the United Nations, Gorbachev had relinquished Moscow’s great gain in World War II: the ideologically conformist regimes that for forty-five years had formed the Soviet Union’s Western security zone.

The United States, although regarded as the liberator of Eastern Europe, had played a remarkably restrained role in 1989. The incoming Bush administration had been rattled by the Gorby mania that had overtaken the world, fearing its challenge to the Western alliance. It also rejected Kissinger’s proposal to establish joint Superpower control over the political changes in Eastern Europe—a détenteera maneuver that the American public and Washington no longer found palatable. On the other hand, although Bush was suspicious of Gorbachev’s motives, he was also hesitant to encourage the Kremlin’s hard-liners to topple the general secretary and use force to maintain Soviet dominance over Eastern Europe.

Facing divisions within his administration, Bush (much like Gorbachev) opted to support gradual transitions in Eastern Europe over radical change, hoping to avoid the political chaos and violence that had occurred in China. Indeed Washington was initially skeptical toward the diverse and disunited Polish opposition movements. Although publicly welcoming the process of reform and proclaiming its dedication to a “whole and free” Europe, Bush offered only modest financial assistance to Poland and Hungary (as did America’s West European allies). During his July visits to Poland and Hungary, the president offered generous praise to the old-guard leaders who were managing the transitions peacefully, thereby helping them to maintain power. Only after November 9, when communist dominance had been shattered, did Washington drop its cautious stance toward the democratic forces in Eastern Europe.

Some scholars regard the Bush-Gorbachev meeting in Malta in December 1989 as the key date in the end of the Cold War.* The cascade of events in Central and Eastern Europe had ended both the Dulles rollback doctrine against the communist empire and the Brezhnev doctrine of forceful intervention to preserve it. Despite bumpy seas, the Malta shipboard summit was amicable. But in the larger realm of US-Soviet relations Gorbachev was a weakened figure. He failed to convince Bush of his objections to SDI, admitted that his economic reforms were foundering, and openly appealed for US help. He also told the president: “We do not consider you an enemy anymore.”

By selecting this moment at the end of 1989, analysts have marked a substantial Soviet defeat: despite their almost parallel policies toward Eastern Europe, the United States and the USSR had achieved an unequal result. While Washington’s efforts to avert violence on the other side of the Iron Curtain had earned it a propaganda victory, Moscow’s loss of all its satellites, unplanned and irretrievable, was a major blow to its prestige and its security. To be sure, just as Britain and France had ultimately benefited from the surrender of their empires, the shedding of its costly and disgruntled dependencies might well have strengthened the USSR and facilitated its entry into a unified Europe. But by allowing Eastern Europe to secede and elect noncommunist governments, Gorbachev had also risked a major political backlash within the Soviet Union itself.†

Nothing symbolized the Cold War more strongly than the division of Germany. The Soviets’ control over East Germany had been a major gain for Stalin, and his successors had been committed to maintaining the Kremlin’s strongest and most orthodox Warsaw Pact member. And although the Western powers officially favored reunification, they had not counted on its actually happening and were content to retain the Federal Republic as a major pillar of NATO and the European Community.

The conservative nationalist West German chancellor Helmut Kohl had a different goal: to unite and free his people from Superpower control. Sensing that the collapse of the GDR was imminent, Kohl seized the moment of the fall of the Berlin Wall to demand the right of all Germans to self-determination. Before the Bundestag on November 28, he announced his Ten-Point program calling for free elections in the GDR and the eventual reunification of Germany within a “pan-European framework.”

Kohl’s speech shocked the West as much as the East. Germany’s NATO allies Britain and France, who had not been consulted beforehand, were as horrified as Poland and the Soviet Union at the sudden prospect of a united Germany, eighty-two million strong. Kohl, with no timetable in mind, was insistent: the continuing flood of refugees and the GDR’s rapid disintegration compelled Bonn to respond forcefully and expeditiously.

Kohl’s only supporter was Bush, who immediately backed the Ten-Point program. The president, recognizing the risks and opportunities created by the fall of the Berlin Wall, was determined to steer the German question in an American direction. Alert to the dangers of a neutral Germany, Bush pressed Kohl to accept full NATO membership for a reunified Germany as the price of US support and then took on the task of convincing the Soviets and the West Europeans to accept both. At Malta he assured Gorbachev that the United States would not seek advantage from the German question. At the NATO summit in December 1989 Bush quashed Thatcher’s vociferous objections and won over French president François Mitterrand by agreeing to tie German reunification to deeper European integration and to the construction of a European monetary union.

As 1990 began, Bush sought to exploit this moment of Soviet weakness and GDR decline to exert leadership over the process of German reunification. The US State Department devised an ingenious solution—the “2 + 4”—in which the two Germanys would negotiate the substance of reunification while the four occupying powers (Britain, France, the United States, and the USSR) would confer over the international aspects. Bush convinced all the parties that their interests would be served.

Nonetheless, the key to German unity was still in Moscow. By February 1990, when Kohl traveled to the Soviet capital, Gorbachev had radically changed his stance—moving from anger over the Ten-Point plan to acceptance of German reunification. It was a daring step, not only reversing decades of Soviet policy but also negating the Soviet population’s still-vivid memories of the bloodletting in World War II. Gorbachev had agreed with Bush that the Germans could now be trusted. But his abrupt abandonment of the GDR was also based on practical considerations, on the hope of substantial direct German aid in modernizing the Soviet economy—an initiative the United States had declined to join.

Trouble arose immediately over Germany’s NATO membership. Exposing the huge extent of Washington’s potential triumph, it posed a danger to Gorbachev’s political survival and was firmly resisted by the Kremlin. Bush (without consulting his NATO partners) responded by proposing a radical overhaul of the alliance, and at his summit meeting with Gorbachev in Washington in May the president added the prospect of a grain and trade agreement and a commitment to speed up the current arms control negotiations to gain Gorbachev’s agreement. He convinced the Soviet leader that, according to the principles of the Helsinki Final Act, “a sovereign state had the right to choose its own alliances.”

When protests by outraged Soviet officials forced Gorbachev to backtrack, Bush (aided by Kohl) pressured their allies to enact reforms. At the London summit on July 5–6, 1990, NATO radically revised its four-decade military strategy and structure, offered to establish formal links with the Warsaw Pact, and proposed to expand and upgrade the role of the CSCE—Gorbachev’s favored instrument for refashioning European security. In its eloquent “Declaration on a Transformed North Atlantic Alliance” NATO assured Moscow that “we are no longer enemies.”

Bush’s strategy prevailed. Ten days later, Gorbachev, his position bolstered by the NATO declaration and his reelection as CPSU general secretary, hosted Kohl in Moscow and the Caucasus. Relieving the German leader’s anxiety, Gorbachev lifted all his objections to reunification, a withdrawal made easier by the Bonn government’s substantial economic concessions, specified in treaties between the two countries.

Under Kohl’s strong hand the inter-German negotiations began promisingly. The GDR’s first free elections in March 1990 had brought victory to the chancellor’s CDU party, which ran on a reunification platform, and the monetary union between West and East Germany (ordained by Kohl over the experts’ overwhelming opposition) took effect on July 1. The East Berlin government, reeling from the exodus of more than two thousand of its citizens each day and pressured by a public demanding unification, formally agreed to accession. Alert to its neighbors’ concerns, the Kohl government assured Moscow that it would assume the GDR’s debts and trade commitments and promised the European Community that it would not request its partners’ aid for the collapsed East Germany.* The Bonn government also agreed to limit the size of the Bundeswehr (the Federal Republic’s army) to 370,000, uphold the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, and maintain its commitment to the existing border with Poland.

After only eight weeks of negotiations, the Treaty on German Unity was signed by representatives of the FRG and GDR on August 31, 1990, and approved by large majorities of both legislatures on September 20. The form of reunification was as important as its occurrence. Instead of a negotiated union between two sovereign governments (which would have necessitated the drafting of a new constitution), the Federal Republic simply incorporated the five new states (Länder) that comprised the former GDR and extended its treaties, political structure, and economic, social, and judicial system to the annexed territory.† The upshot was not only the disappearance of a political entity that in 1990 still maintained diplomatic missions in seventy-three countries but also the ensuing effort by the Federal Republic to erase the GDR’s history and culture (including the names of towns, streets, and buildings) and to convince its former citizens that they were returning to Germany after a forty-one-year absence.

The German-German negotiations were overshadowed by the dramatic events in the Middle East, where, on August 2, 1990, a cash-strapped Iraq had invaded and annexed its wealthy neighbor Kuwait. In this first test of East-West cooperation, Gorbachev supported the UN condemnation of Moscow’s longtime ally. After failing to convince Saddam Hussein to withdraw, the Soviet leader reluctantly endorsed an even tougher US-sponsored resolution threatening the use of force. For the first time since 1956 the United States and the Soviet Union were on the same side.

Not surprisingly, international ratification of the German treaty went smoothly. The four occupying powers agreed to terminate their “rights and responsibilities” in Berlin and in Germany, and the FRG (which had added forty-two thousand square miles and some 16.6 million people) achieved full sovereignty over its internal and external affairs. The final settlement, signed by the foreign ministers of the 2 + 4 governments on September 12 and ratified on October 1 by the foreign ministers of the CSCE meeting in Moscow, took effect two days later. On October 3, 1990, forty-five years after the end of World War II and forty-one years after Germany’s division, the GDR ceased to exist, and the country was reunited.

German reunification, forged by Bush and Kohl, represented a third significant marker in the end of the Cold War and another setback for the Soviet Union. Gorbachev may have traded a difficult satellite for a grateful and potentially generous economic partner, but there was no masking the fact that his passivity and indecision had produced far fewer gains than losses and created a significant backlash at home.

By 1990, the Soviet Union was no longer in a position to block German reunification. Despite his wavering in other instances, Gorbachev remained committed to the principles of his UN declaration. Moreover, the Soviets’ internal weakness prevented him from playing obstructionist politics—either by joining the naysayers Thatcher and Mitterrand or by reviving a Rapallo policy to lure Germany away from the West. Behind Gorbachev’s step-by-step retreat in 1990 was an increasingly chaotic situation in the Soviet Union itself that included a sharp decline in the economy, ethnic violence, and separatist movements as well as growing opposition by the military and the KGB. According to his swelling number of critics, not only had Gorbachev sold out the GDR for a “bowl of porridge,” but he had also ceded his expansive vision of a new Europe based on the CSCE to a revived, renovated, and eastward-moving NATO.

1991: THE COLLAPSE OF THE SOVIET UNION

The collapse of the Soviet Union was an epochal event in world history, brought on by both internal and external causes. Domestically, the sixty-nine-year-old entity disintegrated from above, the middle, and below: destabilized by Gorbachev’s reformist projects that undermined the communist system and the central command economy, challenged by disgruntled and dispossessed Soviet elites, and undermined by grassroots nationalist movements demanding independence.

Outside influences had an almost equal importance. Gorbachev between 1985 and 1989 had substantially reduced the costs of the Soviet Union’s European and overseas empires, drawn down the arms race with the United States, and retreated from Afghanistan. But his liberal foreign policy—his acceptance of the Helsinki human rights principles; his opening the USSR to Western people, media, culture, and ideas; and his allowing the peaceful transformation in Central and Eastern Europe—had all helped to catalyze centrifugal pressures the Kremlin had neither predicted nor was able to control.*

Rebellion began first in the Baltic states, which were the Soviet republics most directly influenced by the events in Poland. On August 23, 1989, the fiftieth anniversary of the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, about one million people from Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania joined hands along the 403-mile road that connected Tallinn, Riga, and Vilnius to protest the “illegal” Soviet occupation. One year later the three republics had virtually declared their independence, and their example was emulated by Georgia, Ukraine, Armenia, and Moldova. Russia, the Soviet Union’s largest and most populous republic, followed. Boris Yeltsin, its populist leader, declared that Russia’s laws had priority over Soviet laws and called for political democracy and a free market.

The international dimension remained significant. While seeking Western aid for perestroika, managing the complex negotiations over Germany, and conducting the difficult CFE† and START negotiations in 1990, Gorbachev applied conciliation rather than force toward the rebellious republics—and he was backed by the Bush administration. Washington, fearing that the disintegration of the Soviet Union would produce political and economic instability and also violence against minorities, took a restrained view toward the separatist movements. Despite America’s long-standing support for the Baltics’ independence, Washington urged their leaders to conduct peaceful negotiations with Moscow.

The struggle over the Soviet Union’s future came to a head in 1991, signaled by departing foreign minister Shevardnadze’s public warning that “dictatorship is coming.” Gorbachev, alarmed over the breakdown of law and order, tacked to the right, appointing a new cabinet of hard-liners who were determined to maintain party control over the state. With the world distracted by the looming war to remove Iraqi troops from Kuwait, Gorbachev in January 1991 dispatched the Soviet military to Lithuania and Latvia to regain control over the breakaway republics, provoking strong criticism at home and abroad. In March he backtracked, proposing a new union treaty designed to preserve the central authority while giving the republics more freedom, but the March 17 referendum to transform the Soviet Union was boycotted by six of the fifteen republics (the Baltic states, Armenia, Georgia, and Moldova).

The Bush administration was divided between the Pentagon’s long-standing desire to destroy the Soviet Union and the State Department’s cautions over destabilizing a known and increasingly accommodating entity. Bush, while still resisting Gorbachev’s pleas for substantial economic aid, continued to support him politically. The US president, although disturbed by the crackdown in the Baltics, repeated his muted reaction two years earlier to the Tiananmen massacre, favoring a familiar partner over a leap into the unknown. In July Bush gave a significant boost to Gorbachev by traveling to Moscow to sign the START treaty: a major accomplishment making significant reductions in the Superpowers’ nuclear arsenals. With the removal of Soviet troops from Central and Eastern Europe, the end of Superpower competition in the Third World, and the close of the nuclear arms race in 1991, the international revolution forged by Gorbachev was completed—and largely on Western terms.

The last Cold War summit in Moscow saw an amicable exchange of views. Bush, who acknowledged Gorbachev’s cooperation in the war against Iraq, envisaged future bilateral cooperation in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Central America—where, however, US power had measurably gained and Soviet influence had greatly diminished. On his stopover in Ukraine, the president praised Gorbachev’s “astonishing achievements,” endorsed the union treaty, and cautioned those seeking independence against promoting a “suicidal nationalism based on ethnic hatred.”*

But three weeks later the Soviet Union began to unravel. Despite warnings of a coup, Gorbachev was taken by surprise. On August 18 Gorbachev was in the Crimea, planning to return to Moscow the next day for the August 20 signing of the union treaty transforming the USSR into a federation of independent republics with a common president, military, and foreign policy.† That day four members of Gorbachev’s inner circle suddenly arrived at his dacha. Intent on blocking the treaty (which they feared would destroy the Soviet Union), they demanded he declare a national state of emergency. When Gorbachev refused, they placed him under house arrest and cut off his communication with the outside world.

The next morning the world learned of the coup. Claiming that Gorbachev was suffering ill health, an eight-member Emergency Committee had taken the reins, sending tanks and troops into Moscow and other Soviet cities and blockading the Baltics. Bush immediately condemned the “unconstitutional resort to force” and called for the restoration of Gorbachev to power. The Soviet population was divided among liberals, such as the poet and parliamentary deputy Yevgeny Yevtushenko, who called on his fellow citizens to defend the Motherland; the communist faithful welcoming the return to centralized power; and a majority of the population that passively awaited the outcome.

The Emergency Committee made several blunders. Among them was the absence of a young, charismatic leader who could offer the public more than a return to the grim Soviet past. They had also failed to secure the support of key military and KGB officers, many of whom refused to carry out their orders. But above all, the conspirators’ failure to arrest Yeltsin changed the course of history. The Russian leader headed to the White House (the seat of the Russian parliament), where he declared the takeover unconstitutional and called on the population to obey only his government. In an extraordinarily potent gesture, Yeltsin placed himself atop a tank and appealed for resistance, whereupon tens of thousands of Muscovites formed a protective cordon around the White House and erected barricades against an impending attack. Crowds also assembled in Leningrad and other major Russian cities. And because the phone lines had not been cut, Yeltsin was able to receive supportive calls from Bush, Kohl, Mitterrand, and British prime minister John Major.

The coup collapsed in three days. The conspirators, unsure of the troops’ loyalty, called off the assault on the White House and allowed Gorbachev to return to Moscow. But the Gorbachev who returned to Moscow was a broken leader. His domestic revolution had been taken over by his rival Yeltsin and by the Russian people, who had defended a democracy yet to be built. After Gorbachev’s efforts to reconstruct the USSR were rebuffed, a triumphant Yeltsin proposed the creation of a far looser Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), which the Baltics and Georgia declined to join, that left no place for the Soviet leader.

The end came swiftly. Yeltsin, in full control of his Russian base, systematically stripped Gorbachev of his authority, and eight of the fifteen republics—including the Slavic heartlands of Belarus and Ukraine—followed the Baltic states and declared their full independence. On Christmas Day 1991 the Soviet Union’s first elected president and its last party general secretary resigned, and that night the hammer and sickle came down from the Kremlin, replaced by the blue, white, and red flag of Russia.

The Bush administration had been in no hurry to dismiss Gorbachev until the remaining Cold War issues were settled. In September 1991, Washington had secured Soviet agreement to withdraw all its troops from Cuba. Subsequently, both sides agreed on a January 1 date to cease sending arms to Afghanistan,* to work together for a UN-mediated peace settlement in El Salvador, and to make major reductions of tactical nuclear weapons on land and sea. In October the United States and the USSR joined China in forging a peace settlement for Cambodia. Finally, in a major shift, the United States offered the Soviet Union a role in the Middle East settlement. At the end of the Gulf War Moscow reestablished diplomatic relations with Israel (which it had severed in 1967), and on October 30, 1991, Bush and Gorbachev jointly convened the Arab-Israeli peace conference in Madrid.

However, by December Washington recognized that Gorbachev’s—and the Soviet Union’s—days were numbered. Bush, under increasing pressure from Ukrainian Americans (and without consulting London, Paris, or Bonn), dropped his neutral stance toward the dissolution of the USSR. On the eve of Ukraine’s December 1 vote on independence, the president outraged Gorbachev and even Yeltsin by signaling his willingness to recognize the new state unconditionally. On December 12 Secretary of State James Baker, in a Princeton address titled “America and the Collapse of the Soviet Empire,” assured the successor republics that the United States was willing to work with them, especially on the issues of security, democracy, free-market economies, and nuclear nonproliferation. After Gorbachev’s resignation, Bush praised the Soviet leader for his “sustained commitment to world peace” but also welcomed the new CIS led by “its courageous president Boris Yeltsin.” Fifty-eight years of US-Soviet relations—begun by Roosevelt in 1933 and destroyed by the implosion of the USSR—were over, leaving even triumphant Americans uncertain of the global and regional consequences.

The Cold War’s third major actor, China, also played a role in the events of 1991. Despite its longtime rivalry with the Kremlin, the Chinese leadership had hoped for the survival of Soviet communism both to bolster its own legitimacy and to restrain Western dominance. After a period of revived acrimony over Gorbachev’s “counterrevolutionary” reforms and his betrayal of Eastern Europe, East Germany, and Iraq, Beijing found it expedient to resume its rapprochement with Moscow. In 1991 China approved high-level visits, increased trade, and, in March, a commodity credit of $750 million at a crucial time, when the United States was punishing Moscow politically and economically for its crackdown in the Baltics. Moreover, the long-postponed visit to Moscow in May by CCP General Secretary Jiang Zemin was an important signal of support for Gorbachev, now facing a more radical rival in Yeltsin.

Beijing, which had also maintained close ties with antireformist factions of the Soviet Communist Party, may well have had foreknowledge of the August coup. After the Emergency Committee seized power, China’s official media responded approvingly and ignored Yeltsin’s words and activities. There was no official response to Gorbachev’s return to Moscow. In its postmortem on the failed coup, the Chinese leadership blamed the Emergency Committee. Infected by Gorbachev’s new thinking, its members had shrunk from a June 4 (Tiananmen Square) response to Yeltsin’s defiance and thereby failed to prevent the collapse of Soviet communism.

Over the next four months Beijing took a pragmatic stance, recognizing the independence of all the republics and offering to establish formal diplomatic relations. Now the world’s largest surviving communist state, China faced the prospect of US global hegemony or a Moscow-Washington détente. At home, Deng Xiaoping’s leftist critics warned of a Soviet-style demise, but the eighty-seven-year-old architect of China’s reforms won the day by insisting that his “nondogmatic methods in the construction of socialism” were the surest way to prevent chaos and catastrophe.

The disappearance of one of the two Superpowers and the world’s first Marxist state—which had played a major role in defeating Nazi Germany, put the first man in space, and for four decades vied with the West in the former colonial world—was a momentous event. Although the global Cold War ended between 1988 and 1990, the Soviet Union was unable to reap the political benefits of a more peaceful world before its dissolution.

In his farewell address Gorbachev proudly reviewed his achievements as a diplomat and world statesman but also acknowledged his failure at home: the old system had collapsed “before the new one had time to begin working.”* Whether or not the Soviet Union was savable (and scholars still disagree over this point), Gorbachev failed to recognize the link between his extraordinary role in ending the Cold War—in particular, relinquishing Soviet control over Central and Eastern Europe—and the collapse of his country in 1991.

Documents

“Bush and Gorbachev at Malta: Previously Secret Documents from Soviet and US Files on the 1989 Meeting, 20 Years Later.” National Security Archive. 2009. http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB298/index.htm.

“A Different October Revolution: Dismantling the Iron Curtain in Eastern Europe.” National Security Archive. 2009. http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB290/index.htm.

“End of the Cold War.” Wilson Center Digital Archive. Accessed February 28, 2013. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/collection/37/end-of-the-cold-war.

“The Fall of the Berlin Wall.” CBS News. Accessed February 28, 2013. http://www.cbsnews.com/2300-500283_162-5554834.html.

Gorbachev, Mikhail. “End of the Soviet Union; Text of Gorbachev’s Farewell Address.” New York Times. December 26, 1991. http://www.nytimes.com/1991/12/26/world/end-of-the-soviet-union-text-of-gorbachev-s-farewell-address.html.

———. “Europe as a Common Home: Address Given by Mikhail Gorbachev to the Council of Europe (Strasbourg, 6 July, 1989). Making the History of 1989.” http://chnm.gmu.edu/1989/archive/files/gorbachev-speech-7-6-89_e3ccb87237.pdf.

Han, Minzhu, and Sheng Hua. Cries for Democracy: Writings and Speeches from the 1989 Chinese Democracy Movement. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990.

Havel, Václav. Open Letters: Selected Writings, 1965–1990. New York: Knopf, 1991.

“Iran-Contra Affair 20 Years On.” National Security Archive. 2006. http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB210/index.htm.

Jiang, Jin, and Qin Zhou. June Four: A Chronicle of the Chinese Democratic Uprising. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1989.

Munteanu, Mircea. “The End of the Cold War.” CWIHP Document Reader. Wilson Center Cold War International History Project. 2006. http://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/the-end-of-the-cold-war.

Oksenberg, Michel, Lawrence R. Sullivan, Marc Lambert, and Qiao Li. Beijing Spring, 1989: Confrontation and Conflict: The Basic Documents. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 1990.

“One Germany in Europe (1989–2009).” German Historical Institute: German History in Documents and Images. Accessed February 28, 2013. http://germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org/section.cfm?section_id=16.

Reagan, Ronald. “Remarks on East-West Relations at the Brandenburg Gate in West Berlin, June 12, 1987.” Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Library. http://www.reaganfoundation.org/tgcdetail.aspx?session_args=EEAA0989-1000-45E4-852F-473AC8E79D37&p=TG0923RRS&h1=0&h2=0&sw=&lm=reagan&args_a=cms&args_b=1&argsb=N&tx=1748.

“The Revolutions of 1989.” National Security Archive. 1999. http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/news/19991105.

“The Reykjavik File: Previously Secret Documents from the US and Soviet Archives on the 1986 Reagan-Gorbachev Summit.” National Security Archive. 2006. http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB203/index.htm.

“To the Geneva Summit: Perestroika and the Transformation of US-Soviet Relations.” National Security Archive. 2005. http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB172/index.htm.

Music

Bernstein, Leonard (conductor). Ode to Freedom: Bernstein in Berlin. Deutsche Grammophon, 1990, compact disc. Recorded in 1989. Includes Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

Films

“The Gate of Heavenly Peace.” Frontline, season 14, episode 12. Directed by Richard Gordon and Carma Hinton. New York: Independent Television Service, 1995.

Good Bye Lenin! Directed by Wolfgang Becker. Berlin: X-Filme Creative Pool, 2003.

The Lives of Others. Directed by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck. Berlin: Bayerischer Rundfunk, 2006.

Summer Palace. Directed by Ye Lou. Beijing/Paris: Dream Factory/Centre National de la Cinématographie, 2006.

Wings of Desire. Directed by Wim Wenders. Berlin: Road Movies Filmproduktion, 1987.

Contemporary Works

Gorbachev, Mikhail Sergeevich. Perestroika: New Thinking for Our Country and the World. Cambridge: Harper and Row, 1987.

———. A Time for Peace. New York: Richardson and Steirman, 1985.

Memoirs

Baker, James Addison. The Politics of Diplomacy: Revolution, War, and Peace, 1989–1992. New York: Putnam, 1995.

Boldin, V. I. Ten Years That Shook the World: The Gorbachev Era as Witnessed by His Chief of Staff. Translated by Evelyn Rossiter. New York: Basic Books, 1994.

Brucan, Silviu. The Wasted Generation: Memoirs of the Romanian Journey from Capitalism to Socialism and Back. Boulder, CO: Westview, 1993.

Bush, George, and Brent Scowcroft. A World Transformed. New York: Knopf, 1998.

Chernyaev, Anatoly S. My Six Years with Gorbachev. Translated and edited by Robert English and Elizabeth Tucker. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000.

Drakulić, Slavenka. How We Survived Communism and Even Laughed. London: Hutchinson, 1992.

Dubček, Alexander, with András Sugár. Dubcek Speaks. London: I. B. Tauris, 1990.

Genscher, Hans Dietrich. Rebuilding a House Divided: A Memoir by the Architect of Germany’s Reunification. Translated by Thomas Thorton. New York: Broadway Books, 1998.

Gorbachev, Mikhail Sergeevich. The August Coup: The Truth and the Lessons. New York: Harper Collins, 1991.

———. Memoirs. New York: Doubleday, 1996.

Gorbachev, Mikhail Sergeevich, and Zdenek Mlynár. Conversations with Gorbachev: On Perestroika, the Prague Spring, and the Crossroads of Socialism. Translated by George Shriver. New York: Columbia University Press, 2002.

Grachev, Andrei S. Final Days: The Inside Story of the Collapse of the Soviet Union. Translated by Margo Milne. Boulder, CO: Westview, 1995.

Iliescu, Ion. Romania at the Moment of Truth. Paris: Editions Henri Berger, 1994.

Li, Lu. Moving the Mountain: My Life in China from the Cultural Revolution to Tiananmen Square. London: Macmillan, 1990.

Ligachev, E. K. Inside Gorbachev’s Kremlin. Translated by Catherine A. Fitzpatrick, Michele A. Berdy, and Dobrochna Dyrcz-Freeman. New York: Pantheon Books, 1993.

Matlock, Jack F. Autopsy on an Empire: The American Ambassador’s Account of the Collapse of the Soviet Union. New York: Random House, 1995.

Palazhchenko, P. My Years with Gorbachev and Shevardnadze: The Memoir of a Soviet Interpreter. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997.

Sakharov, Andrei. Moscow and Beyond, 1986–1989. Translated by Antonina W. Bouis. New York: Knopf, 1991.

Shultz, George Pratt. Turmoil and Triumph: My Years as Secretary of State. New York: Scribner’s, 1993.

Thatcher, Margaret. The Downing Street Years. New York: Harper Collins, 1993.

Wałesa, Lech. The Struggle and the Triumph: An Autobiography. Translated by Franklin Philip and Helen Mahut. New York: Arcade, 1992.

Fiction

Cheng, Terrence. Sons of Heaven: A Novel. New York: William Morrow, 2002.

Grass, Günter. Too Far Afield. Translated by Krishna Winston. New York: Harcourt, 2000.

Schneider, Peter. The Wall Jumper: A Berlin Story. Translated by Leigh Hafrey. New York: Pantheon Books, 1983.

Wang, Annie. Lili: A Novel. New York: Anchor Books, 2002.

Wolf, Christa. What Remains and Other Stories. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1993.

Yevtushenko, Yevgeny Aleksandrovich. Don’t Die Before You’re Dead. Translated by Antonina W. Bouis. New York: Random House, 1995.

Secondary Sources

Adamishin, A. L., and Richard Schifter. Human Rights, Perestroika, and the End of the Cold War. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press, 2009.

Beissinger, Mark R. Nationalist Mobilization and the Collapse of the Soviet State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Beschloss, Michael, and Strobe Talbott. At the Highest Levels: The Inside Story of the End of the Cold War. Boston: Little, Brown, 1994.

Bozo, Frédéric. Mitterrand, the End of the Cold War and German Unification. New York: Berghahn Books, 2009.

Bradley, J. F. N. Czechoslovakia’s Velvet Revolution: A Political Analysis. Boulder, CO: East European Monographs, 1992.

Brook, Timothy. Quelling the People: The Military Suppression of the Beijing Democracy Movement. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Brown, Archie. The Gorbachev Factor. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

———. Seven Years That Changed the World: Perestroika in Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Chafetz, Glenn R. Gorbachev, Reform, and the Brezhnev Doctrine: Soviet Policy Toward Eastern Europe, 1985–1990. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1993.

Checkel, Jeffrey T. Ideas and International Political Change: Soviet/Russian Behavior and the End of the Cold War. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997.

Collins, Alan. The Security Dilemma and the End of the Cold War. New York: St. Martin’s, 1997.

Combs, Dick. Inside the Soviet Alternate Universe: The Cold War’s End and the Soviet Union’s Fall Reappraised. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2008.

D’Agostino, Anthony. Gorbachev’s Revolution. New York: New York University Press, 1998.

Dannreuther, Roland. Creating New States in Central Asia: The Strategic Implications of the Collapse of Soviet Power in Central Asia. London: Brassey’s for the International Institute for Strategic Studies, 1994.

Dockrill, Saki Ruth. The End of the Cold War Era: The Transformation of the Global Security Order. New York: Oxford, 2003.

Ekedahl, Carolyn McGiffert, and Melvyn A. Goodman. The Wars of Eduard Shevardnadze. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997.

English, Robert. Russia and the Idea of the West: Gorbachev, Intellectuals, and the End of the Cold War. New York: Columbia University Press, 2000.

FitzGerald, Frances. Way out There in the Blue: Reagan, Star Wars, and the End of the Cold War. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2000.

Freedman, Lawrence, and Efraim Karsh. The Gulf Conflict, 1990–1991: Diplomacy and War in the New World Order. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993.

Gaddis, John Lewis. The United States and the End of the Cold War: Implications, Reconsiderations, Provocations. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Garthoff, Raymond L. The Great Transition: American-Soviet Relations and the End of the Cold War. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1994.

Garton Ash, Timothy. In Europe’s Name: Germany and the Divided Continent. New York: Random House, 1993.

———. The Polish Revolution: Solidarity. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2002.

Grachev, A. S. Gorbachev’s Gamble: Soviet Foreign Policy and the End of the Cold War. Cambridge: Polity, 2008.

Hahn, Gordon M. Russia’s Revolution from Above, 1985–2000: Reform, Transition, and Revolution in the Fall of the Soviet Communist Regime. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2002.

Hutchings, Robert L. American Diplomacy and the End of the Cold War: An Insider’s Account of U.S. Policy in Europe, 1989–1992. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 1997.

Jarausch, Konrad Hugo. The Rush to German Unity. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Kotkin, Stephen. Armageddon Averted: The Soviet Collapse, 1970–2000. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Kuzio, Taras, and Andrew Wilson. Ukraine: Perestroika to Independence. New York: St. Martin’s, 1994.

Lévesque, Jacques. The Enigma of 1989: The USSR and the Liberation of Eastern Europe. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

Lieven, Anatol. The Baltic Revolution: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and the Path to Independence. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993.

Maier, Charles S. Dissolution: The Crisis of Communism and the End of East Germany. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997.

Matlock, Jack F. Reagan and Gorbachev: How the Cold War Ended. New York: Random House, 2004.

Meyer, Michael. The Year That Changed the World: The Untold Story Behind the Fall of the Berlin Wall. New York: Scribner, 2009.

Oberdorfer, Don. From the Cold War to a New Era: The United States and the Soviet Union, 1983–1991. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Ost, David. Solidarity and the Politics of Anti-Politics: Opposition and Reform in Poland Since 1968. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1990.

Pond, Elizabeth. Beyond the Wall: Germany’s Road to Unification. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1993.

Prados, John. How the Cold War Ended: Debating and Doing History. Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2011.

Sarotte, Mary E. 1989: The Struggle to Create Post–Cold War Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009.

Schweizer, Peter. Reagan’s War: The Epic Story of His Forty-Year Struggle and the Final Triumph over Communism. New York: Doubleday, 2002.

Sebestyen, Victor. Revolution 1989: The Fall of the Soviet Empire. New York: Pantheon Books, 2009.

Siani-Davies, Peter. The Romanian Revolution of December 1989. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005.

Snyder, Sarah B. Human Rights Activism and the End of the Cold War: A Transnational History of the Helsinki Network. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Stokes, Gale. The Walls Came Tumbling Down: The Collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Suny, Ronald Grigor. The Revenge of the Past: Nationalism, Revolution, and the Collapse of the Soviet Union. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1993.

———. The Soviet Experiment: Russia, the USSR, and the Successor States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Tokés, Rudolf L. Hungary’s Negotiated Revolution: Economic Reform, Social Change, and Political Succession, 1957–1990. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Vogele, William B. Stepping Back: Nuclear Arms Control and the End of the Cold War. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1994.

Zelikow, Philip, and Condoleezza Rice. Germany Unified and Europe Transformed: A Study in Statecraft. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, 1996.

Zheng, Zhuyuan. Behind the Tiananmen Massacre: Social, Political, and Economic Ferment in China. Boulder, CO: Westview, 1990.

![]()

* Breaching the SALT II limitations that each side had agreed upon.

† The first involving the arrest and death sentences against US spies in the USSR based on information provided by the CIA double agent Aldrich Ames; the second over Soviet retaliation for the arrest of its KBG agent Gennady Zakharov with the arrest of the US correspondent Nicholas Daniloff.

* After seven US hostages were seized by a pro-Iranian group in Lebanon, Reagan in 1985 secretly authorized arms sales to Iran to secure their release, whereupon a member of the president’s National Security Council, Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North, diverted some of the substantial profits to support the Contras. When news of these illegal transactions broke in November 1986, Reagan denied all knowledge, thereby tarnishing either the president’s credibility or his ability to manage his underlings.

* “There is one sign the Soviets can make that would be unmistakable, that would advance dramatically the cause of freedom and peace. General Secretary Gorbachev, if you seek peace, if you seek prosperity for the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, if you seek liberalization come here to this gate. Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate. Mr. Gorbachev, Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” The Soviet press agency Tass called it an “openly provocative, war-mongering speech.”

† NATO in 1979 had coupled the deployment of US Pershing and cruise missiles in Western Europe with a call for negotiations with the Soviet Union to limit total deployments.

* Gorbachev’s retreat was magnified when, in the April 1988 UN-brokered Geneva Accords on Afghanistan, the United States reversed its earlier pledge to cease providing arms to the insurgents after the Soviet troop withdrawal. Both sides continued to pour in weapons until 1992, and there is some evidence that a small number of Soviet troops remained as well.

† Which Chernyaev, in a reference to Churchill’s 1946 Iron Curtain speech, called “Fulton in reverse.”

* Nonetheless, the first triumphalist interpretation came from US senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who called Gorbachev’s UN speech “the most astounding statement of surrender in the history of ideological struggle.”

* Among them the playwright Václav Havel, who would become president of Czechoslovakia at the end of the year.

† Later that year, in an interview on a US television program, Gerasimov characterized the Kremlin’s decision as the “Sinatra doctrine,” after the US crooner’s song “I Did It My Way.”

* The acronym for the Ministerium für Staatssicherheit, the GDR’s secret service, which employed anywhere between a half and two million informers.

* Gorbachev, reportedly shocked at the size of the GDR’s $26.5 billion debt and its $12.1 billion budget deficit, had warned that the Soviets could not save East Germany.

* This figure does not include Albania, whose long-standing communist regime collapsed in 1990, or Yugoslavia, which began its violent disintegration after 1990.

* Significantly, that month the president ordered an invasion of Panama to topple a former ally, General Manuel Noriega, America’s first military operation since 1945 not justified by a communist threat.

† In a test of Gorbachev’s pledge of noninterference, the legislatures in Lithuania, Estonia, and Latvia in May and June 1989 had declared the preeminence of their laws over those of the Soviet Union.

‡ There are two terms, “reunification” and “unification,” to describe the epochal event in 1990. The former, referencing Germany’s initial unification under Bismarck in 1871, was widely used in 1989 after the wall fell down; the latter originated with those claiming that the events of 1990 had led to the creation of an entirely new German entity that had never existed before. To avoid this controversy, FRG politicians introduced the neutral term “Deutsche Einheit” (German unity) in 1990; many historians use the two terms interchangeably.

* Although by financing the rehabilitation of East Germany not only by taxes but also by raising interest rates, the FRG indirectly forced its European partners to share the burden of reunification.

† The 1949 Basic Law had to be amended in several significant ways to formalize the process of reunification.

* One of the first signs of trouble was the outbreak of ethnic violence in 1988 in Azerbaijan, which spread to Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, and Georgia and which the Kremlin had difficulty controlling. There were also riots in Tajikistan and Kirghizia (Kyrgyzstan) requiring intervention by Soviet troops.

† A treaty on reducing conventional forces in Europe, begun in 1973 between NATO and the Warsaw Pact.

* A right-wing New York Times columnist dubbed Bush’s August 1 speech “Chicken Kiev,” claiming its pro-Gorbachev sentiments had flattened the spirits of those seeking independence from the Soviet Union.

† The eight republics that were to form the Union of Sovereign States were: Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan. Ukraine, which had participated in the March referendum, rejected the treaty.

* Leading to the fall in April 1992 of the Soviet-backed Najibullah regime, followed by a brutal four-year-long civil war that ended with the Taliban’s seizure of power in 1996.

* “We live in a new world. The Cold War has ended, the arms race has stopped, as has the insane militarization which mutilated our economy, public psyche and morals. The threat of a world war has been removed. . . . Everything was done . . . to preserve reliable control of the nuclear weapons. We opened ourselves to the world, gave up interference into other people’s affairs, [and] the use of troops beyond the borders of the country, and trust, solidarity and respect came in response.”