Chapter Ten

in which a Harvest Festival is held in the Forest and Christopher Robin springs a surprise

SUMMER WAS ALMOST OVER. The windfall apples lay on the ground, which was heavy with dew, and one morning there was mist curling in the hollows down by the stream.

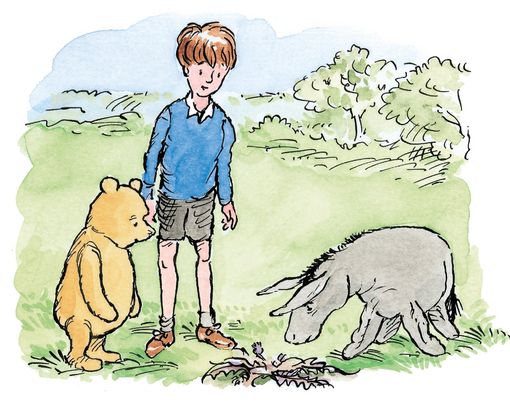

Christopher Robin and Pooh were paying an Encouraging Visit to Eeyore, who was gloomier than ever. But after a few minutes Eeyore was showing no sign of being Encouraged, and his friends were running out of things to say.

“Did you know that it will soon be Harvest Festival?” asked Christopher Robin, after a particularly long silence.

“What’s that then?” asked Eeyore suspiciously.

“Well, every September, people get together to celebrate the Gathering-in of the Crops,” explained Christopher Robin. “They make corn dollies and collect produce and put it on display. Then they sing about everything being bright and beautiful.”

“Is it?” Eeyore asked. “Can’t say I’d noticed.”

“What’s produce?” asked Pooh.

“It’s food that you’ve got to spare, Pooh. Like a pot of honey.”

“It is?” Pooh said, wondering if honey could be spare.

“Yes, and it ought to be the best pot. The idea is to give things to the Less Fortunate.”

Pooh gulped, thinking of his row of honey jars, especially the pot second from the left at the back, which was the tallest and the fattest.

“Who are the Less Fortunate?” asked Pooh. He felt that he would be one of them, if he had to give away his honey.

“Well, I’m not sure,” said Christopher Robin. He lay on his back, looking up at the sky with a thoughtful expression. “We could have a Harvest Festival here in the Forest,” he said. “I could build a cart to put the produce in and tow it behind my bicycle. Then the Less Fortunate could see it and take things.”

“You’ll do as you like, of course,” said Eeyore loudly, “but I’m not singing. Bad for thestomach.”

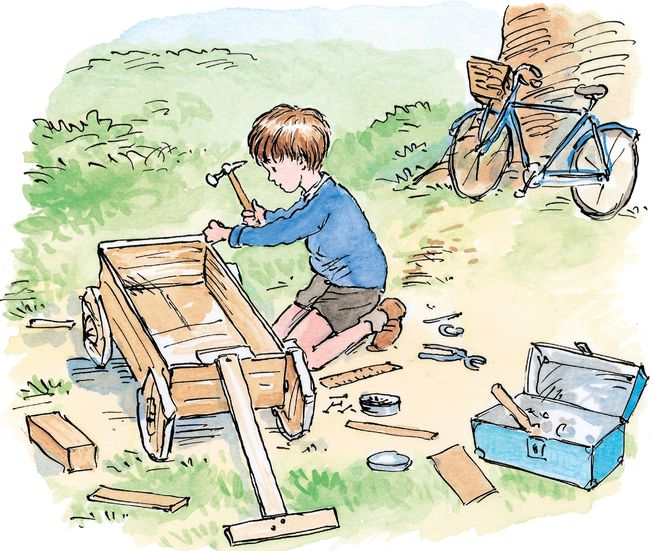

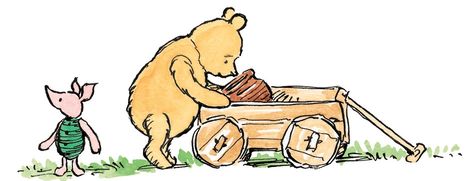

Although Christopher Robin had learned carpentry at school, nobody had shown him how to make a cart, and it turned out to be quite tricky.

The wheels ended up rather squarish, and when he came to make the tires there was no rubber, so he used a pair of old pajamas instead. Then there was the question of how to attach the cart to the chassis, and the chassis to the axle, and the axle to the wheels. Working all this out involved a lot of sitting around scratching his head and turning bits of wood over in his hands,but eventually the cart was finished. It was rather bumpy and hard to pull along, but a cart it certainly was.

Christopher Robin parked it in front of his house with a sign which read:

FOR PRODUSE. PUT IN HERE PLEEZ.

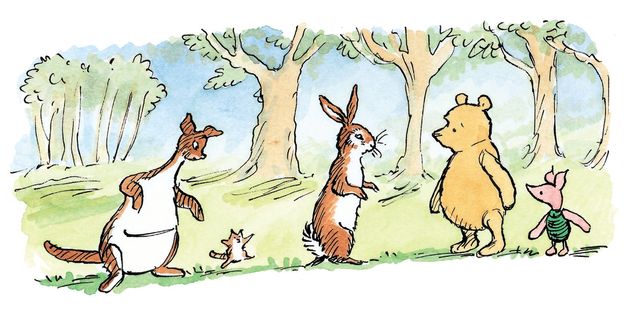

Once the animals had gathered around to admire the cart, everyone started to make suggestions for what else they could do to celebrate Harvest Festival. Kanga suggested baking cakes—always popular—and Rabbit suggested card games, like Snap, Old Maid, and Racing Demon—not so popular, as Rabbit generally boasted when he won and sulked when he lost—but it was Christopher Robin who came up with a clever suggestion that would allow them to do all these things and more.

“It’s a bit late in the summer,” he said, “but why don’t we have a fête? We could have blackberries and cream, instead of strawberries, and play games like Ring Toss and Pin the Tail on the Donkey.”

All the animals cheered—with the exception of Tigger, who thought he wouldn’t eat any more blackberries; and Eeyore, who said, “Excuse me,” with great dignity. Then he said it twice more until everyone else was quiet.

“I believe, Christopher Robin,” he continued, “you will find that I already have a tail. True, it is attached by a nail, but you will understand my reluctance to have just anyone bashing away at it.”

“Oh, Eeyore,” said Christopher Robin. “I didn’t mean you should...”

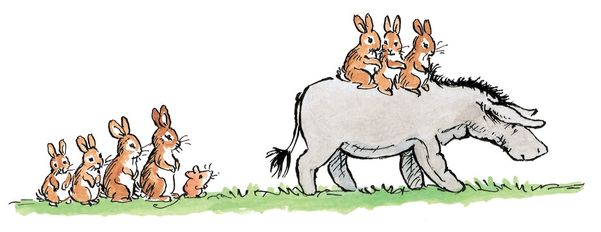

But the old donkey held up a hoof for silence. “I shall give rides to the little ones instead,” he announced.

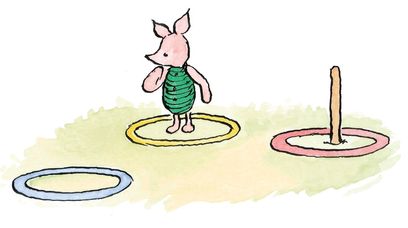

The morning of the Harvest Festival dawned bright and clear. Everyone had been planning and working for days, and by lunchtime the fête was set up. There were stalls selling the bric-a-brac that had turned up when Rabbit helped everyone clear out their houses and a Ring Toss game made from sticks and rings, and Owl’s platform where he would stand to recite poetry and a mysterious booth made out of blankets hung over tree branches. HAVE YOUR PAW READ BY MADAME PETULENGRA said a sign that was pinned to the outside.

In the middle of it all sat the cart, full of produce that gleamed in the September sunshine. There were haycorns from Piglet, a small pot of honey from Pooh, Strengthening Medicine from Tigger, homemade crab-apple jam from Rabbit, a whole tray of fairy cakes from Kanga, and much, much more. It had all been decorated with heather and yellow gorse.

“Perfect,” said Christopher Robin, looking around the glade when preparations were complete. “And now it’s time for our picnic,” he added as one of the fairy cakes was grabbed from the cart by a baby rabbit.

The lunch was a fine one, with enough honeycomb and haycorns to suggest that perhaps not all the best produce had been set aside for the Less Fortunate.Then, as the sun started its journey down the other side of the sky, the animals opened their fête.

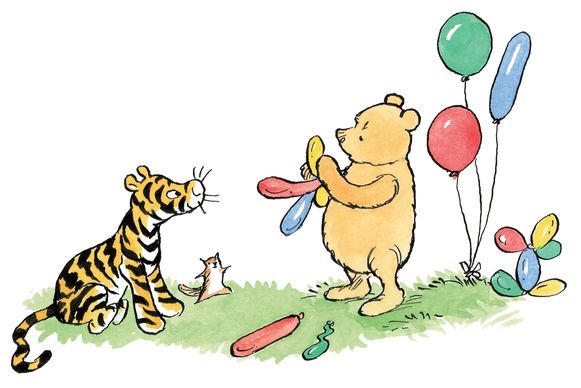

From the start, Piglet’s Ring Toss stand was popular. It became especially busy when some of Rabbit’s Friends and Relations decided to throw the rings over Piglet instead of over the pegs. Things only calmed down again when Tigger got a ring wedged around his head and Christopher Robin had to remove it with soapy water.

The mysterious blanket booth turned out to contain Lottie, seated in a rocking chair and wearing a mauve turban. If you paid her a small coin and offered her your paw to examine, she would tell you either that you would cross the water or that you would meet with a handsome stranger. If you paid her a large coin, you found out you were going to do both at the same time.

Meanwhile, Eeyore tramped slowly around the glade, with a crowd of little rabbits clinging to his back, shrieking with laughter.

Then, when you tired of these wonderful things, you could go to Rabbit’s card booth and find yourself obliged to lose at various different games. Or you could  listen to Owl reciting Uncle Robert’s favourite poem, but it was a very long poem and when it came to the hard-to-remember bits, Owl flapped his wings a few times and said “etcetera,” “and so forth,” “and so on” in such a grand way that it was really just as good as the poem. Or you could do as Pooh did, and wander around from stall to stall, marveling at everything, trying all the games, and not doing terribly well at anything, except at rolling the penny.

listen to Owl reciting Uncle Robert’s favourite poem, but it was a very long poem and when it came to the hard-to-remember bits, Owl flapped his wings a few times and said “etcetera,” “and so forth,” “and so on” in such a grand way that it was really just as good as the poem. Or you could do as Pooh did, and wander around from stall to stall, marveling at everything, trying all the games, and not doing terribly well at anything, except at rolling the penny.

And so the celebrations went on all afternoon, until Kanga announced that, Harvest Festival or not, it was time for Roo to go home to bed.

“But it won’t be dark for hours,” protested Roo.

“Now, I’ve told you—” started Kanga.

But Pooh wasn’t listening to this. He was looking around the glade, for something that wasn’t there.

“Where is Christopher Robin?” he asked.

Everybody stopped what they were doing.

Rabbit looked from side to side, and said, “He isn’t here.”

“I know where he isn’t,” said Pooh, “but there’s still a lot of other places he might be.”

“We must Organdise a Search Party!” squeaked Roo excitedly.

“No, dear,” said Kanga, “because then we might all get lost instead of just Christopher Robin.”

“He isn’t lost,” said Piglet, sounding as if he wasn’t quite sure. “We don’t know where he is, but that isn’t the same thing at all. Christopher Robin is just on his own somewhere. I wonder if that means he wants to be on his own...Oh dear.”

It was then that Owl, whose eyesight was the best, flew up above the tallest of the tall oaks. But even with his sharp eyes there was no Christopher Robin to be seen.

Eeyore looked around the remains of the fête and sniffed. “Well then,” he said, “if that’s the end of that, I’d better be going.” But he did not leave.

“Roo, dear, it really is time for bed!” said Kanga, her voice becoming quite sharp.

But nobody moved.

Pooh kept looking at the cart and the pot of honey. He was sure he had seen Tigger helping himself to a gulp or two of the Strengthening Medicine, and Piglet retrieving one or five of the finest haycorns. So he thought to himself that there was no harm in having just a little taste of the honey.

By the time he was on to his ninth or tenth taste, he could hear a faint clunking and clattering sound. He looked around at the others, and they were all listening too.

“That sounds like a bicycle,” he said.

“And if it’s a bicycle,” said Piglet, “there must be somebody on it to do the pedaling, and the only one who isn’t here is Christopher Robin, and he’s the only one with a bicycle.”

Piglet was quite correct. It was Christopher Robin’s bicycle and Christopher Robin was riding it.

Everyone breathed a sigh of relief when Christopher Robin came rattling into the glade on his bicycle. He jumped off and leaned it against a tree.

“Sorry I left the party, but I wanted to fetch you a little surprise,” he explained.

From his bicycle basket, he took some large objects that were carefully wrapped in old jerseys. They turned out to be the gramophone and a box of records. The animals watched as he unwrapped them and set them down on the grass.

“I thought we could finish the day with some dancing,” he said cheerfully. “Then I will take your generous presents to the Less Fortunate.”

Christopher Robin glanced into the cart, and then peered inside more closely.

“Or maybe I won’t,” he added. Then he leant over the gramophone to wind the handle, and finished quietly, “Anyway, I’m leaving this here for you.”

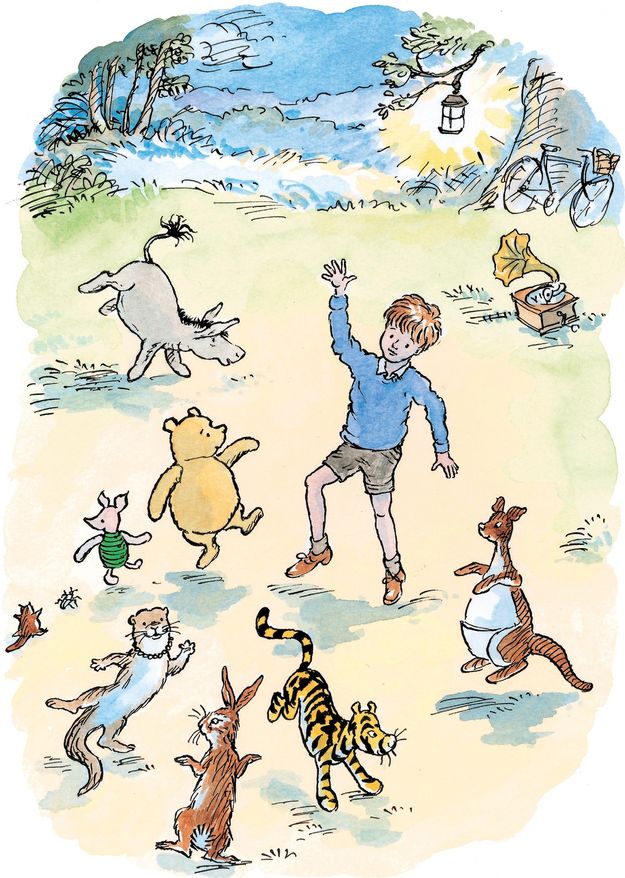

Then the loudest, jumpiest, most harmonious and tumultuous music came tumbling out of the gramophone horn—and nobody could stay still.

Shake your feathers

Move your feet about

For I’m sweet about you.

Feel the beat because

I’m incomplete because

I am lost without you.

Move your feet about

For I’m sweet about you.

Feel the beat because

I’m incomplete because

I am lost without you.

They danced a proper Hundred Acre Wood dance this time. At first it owed something to Lottie’s dancing class, but then it became wilder, with much leaping up into the air. Tigger and Kanga vied to see who could jump highest—the results were pretty even—and Roo and Piglet vied to see who could crouch down lowest —they were both beaten by Henry Rush, who hurried into a clump of heather immediately afterwards, for fear of being trodden on. And even Eeyore danced, a dance all his own, with flying hooves and mane and loud braying and his tail going here, there, and everywhere.

After “Shake Your Feathers,” they played “The Bam Bam Bammy Shore” and “Yes, We Have No Bananas” and “My Grandfather’s Clock.” And while “The Bam Bam Bammy Shore” was playing for the second time, Christopher Robin stopped dancing, and rolled up the jerseys, and put them in the basket of his bicycle.

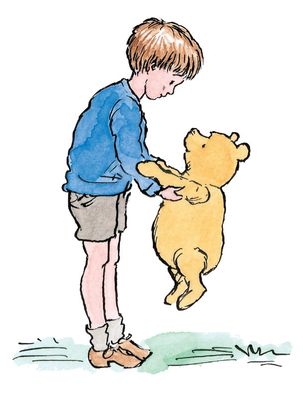

Pooh, who was by now rather tired, left the dance as well. He padded over to see what Christopher Robin was doing, although he thought he could guess.

“Ah,” said Pooh solemnly, because this was one of those moments when you had to say something, even though nothing was quite right for the occasion.

“Well then, Pooh,” said Christopher Robin, leaning his bicycle back against the tree.

“So . . .”

He stopped to give Pooh a hug. It was a bit awkward, because Christopher Robin was quite tall these days, but Pooh hugged him back as best he could.

Over Pooh’s head, Christopher Robin finished, “I’ll be away for a while again, but I know you’ll look after the Forest.”

“I’ll try,” said Pooh. Really, he wasn’t sure what Looking After the Forest might involve. But if Christopher Robin thought he could do it, that meant that he could.

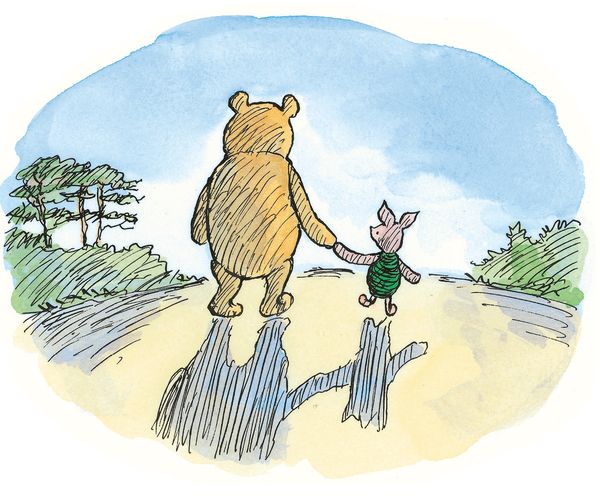

Christopher Robin let go and gave Pooh a nod. He got on his bicycle and pedaled swiftly away, turning just once to give a last wave and a smile before he was lost among the trees.

Later, after Owl and Rabbit had had an argument over who would look after the gramophone and the records, and Lottieand Eeyorehadsolved theargument by carrying off the whole lot between them, Pooh and Piglet walked home through the moonlit wood.

“I wonder why things have to change,” murmured Piglet.

Pooh thought for a while, then said, “It gives them a chance to get better. Like when the bees went away and came back””

“I suppose so,” said Piglet, a bit hesitantly. Then he cheered up. “It’s been a good summer, really. Do you remember that six I hit to win the cricket match?”

“I do,” said Pooh, a bit less cheerfully than Piglet, as he also remembered being hit on the nose by the cricket ball. And he remembered Piglet going down the well, and the Census, and the Academy, and the produce, and the gramophone. It all seemed mixed up with the fluff in his head, but at the same time it was so special that it deserved a hum. So he sat down on a log and made one up.

Christopher Robin has gone away.

He would not stay, no, he would not stay.

When will we see him? Will he be back?

Did he even have time to pack?

He would not stay, no, he would not stay.

When will we see him? Will he be back?

Did he even have time to pack?

He left his music, but took his machine,

The best and the bluest we’d ever seen.

He left us all wondering: Gone for good?

No! He’ll be back to our lovely wood.

The best and the bluest we’d ever seen.

He left us all wondering: Gone for good?

No! He’ll be back to our lovely wood.

One day perhaps when the sun is high,

Out of the blue we will hear him cry:

“Piglet and Eeyore, Rabbit and Pooh,

I’m back again to spend time with you.”

Out of the blue we will hear him cry:

“Piglet and Eeyore, Rabbit and Pooh,

I’m back again to spend time with you.”

“I’ve singed it, but I haven’t signed it,” said Pooh, “because I can’t write.”

“Doesn’t matter,” said Piglet. “I was worried you weren’t going to put me in like you always used to. But then at the end you did.”

“You don’t rhyme with very much,” said Pooh.

“Are there many rhymes for Christopher Robin?” wondered Piglet.

“I don’t think so. Not good ones.”

“We could go and ask him tomorrow.”

Then they remembered that Christopher Robin wouldn’t be there tomorrow, or the next day.

So off they went, together. And if you pass by the Hundred Acre Wood on an early autumn evening, you might see them, arm in arm, strolling contentedly under the trees, until they are swallowed up by the mist.

DAVID BENEDICTUS’S stories were inspired by his familiarity with Pooh’s adventures after having worked on audio book adaptations of previous Winnie-the-Pooh tales. The author of over twenty books, he has also worked as a journalist, director, and teacher. In writing Return to the Hundred Acre Wood, Mr. Benedictus hopes to “both complement and maintain Milne’s idea that whatever happens, a little boy and his Bear will always be playing.”

MARK BURGESS has been illustrating children’s books for many years and has drawn countless classic characters, including Paddington Bear and Winnie-the-Pooh. He spends his free time reading, gardening, and walking in the woods near his home in southwest England, where he lives with his wife and cat. Mr. Burgess illustrated this sequel in the style of E. H. Shepard with the approval of Mr. Shepard’s estate.

A. A. MILNE (1882-1956) was a playwright and a journalist as well as a poet and storyteller. Inspired by his son, Christopher Robin, Milne published his first stories about Pooh in 1926. An instant success, Milne’s children’s books have since sold millions of copies and been translated into fifty languages.

ERNEST H. SHEPARD(1879-1976) gained renown as a cartoonist and illustrator. His witty and loving illustrations of Winnie-the-Pooh and his friends have become an inseparable part of the Pooh stories.