IN EARLY DECEMBER 1914, THE HABSBURG ARMY HAD THE MISsion to halt the relentless Russian westward pressure. Though the influx of tsarist troops into the Carpathian Mountain passes posed a critical military threat as they became more active, the Austro-Hungarian army simply lacked sufficient troop numbers to counter them. Furthermore, three and one-half months of continuous fighting and marching had seriously weakened its forces. Division strengths had been reduced from 12,000–15,000 soldiers to 2,000–3,000, and Slavic national replacement troops reputedly proved unreliable in battle, a foreboding sign that undermined Austro-Hungarian troop morale on the Carpathian Mountain front. There were serious deficiencies in transporting artillery shells, which steadily worsened, while Fortress Przemyśl artillery capabilities also began to decline rapidly. Gun tubes deteriorated and could not be replaced, thus effective artillery range dropped precipitously. Shells had to be conserved, and certain caliber rounds had already been depleted, placing multiple guns out of action.1 How long the fortress could endure its siege depended to a great extent on the number of horses available for duty to provide artillery maneuverability and sortie efforts. Nevertheless, General Conrad remained fixated on his military objectives—to liberate Galicia and Fortress Przemyśl by outflanking tsarist extreme left flank positions, despite the fact that the prewar-trained k.u.k. Armee had all but disappeared on the bloody battlefields. On December 1, at a conference in Posen, General Ludendorff argued that he must receive reinforcements on the eastern front to prevent Austria-Hungary from being defeated.

Given the deplorable battle and supply conditions and the transfer of much of the Habsburg Second Army troop components to the German front, postponing further offensive efforts until spring seemed plausible, but General Conrad desperately needed a major victory against the Russians to restore the damaged Habsburg military reputation after so many battlefield defeats. In early December, the Dual Monarchy was gravely embarrassed by the defeat on the Balkan front, creating an extremely unfavorable military situation in that war theater and destroying any remaining Habsburg prestige in the Balkan Peninsula. The German military command pressured General Conrad to rectify that inglorious defeat, but the primary motivation for his launching a Habsburg offensive in the Carpathian Mountains stemmed from the threat of neutral Italy and Romania entering the war (partly because the Habsburg government had refused Italy’s demand for territorial concessions to maintain its neutrality). Both countries sought to obtain irredenta lands from the Dual Monarchy, but awaited definitive battlefield results against Austro-Hungarian forces before entering the conflict to assure easy seizure of these desired territories. As a result, a decisive change in the unfavorable Habsburg military situation appeared unlikely in the near future. The perilous frontline gap between Fortress Kraków and the Carpathian Mountain ranges continued to widen while Russian Third Army troops maneuvered from the Fortress Przemyśl environs. Meanwhile, the Galician and Polish fronts settled into a semi-trench line.

By December it had become evident that the Russians’ numerical superiority, combined with unfavorable terrain and weather conditions, would negatively affect any attempts to liberate Fortress Przemyśl. However, the declining fortress food supply and worsening troop conditions demanded rapid action. An effective offensive operation to liberate the citadel could be launched only from the Carpathian Mountains, about eighty kilometers from the fortress.

December thus introduced an especially difficult and eventful month for Habsburg military fortunes. Fortress Przemyśl continued to launch costly sorties, while the exhausted and demoralized Third Army continued its efforts to liberate the fortress. Mounting casualties and the chronic shortage of troop numbers, including a lack of reinforcement and replacement troops, posed a serious problem. The declining Habsburg troop numbers also resulted in a series of daily military crises. Unrelenting battle, long marches, sickness, and frostbite claimed many lives. In addition, the campaign region’s lack of suitable roadways and its reliance on a single-track, small-capacity railroad line made the rapid transport of any available troops, supplies, and reinforcements an enormously difficult task.

The Habsburg retreat into the Carpathian Mountain range in early December left the major mountain crossings unprotected, and pitched battle soon erupted at the critical Laborcza valley railroad center at Mezölaborcz. Military action in this region continued until the loss of Mezölaborcz in February 1915, which proved detrimental to all efforts to liberate Fortress Przemyśl, as its two-track railroad line was absolutely necessary for such an operation.

Despite these hardships, the battle of Limanova-Lapanov, fought between December 2 and 11, finally produced the first major Habsburg military victory over previously undefeated tsarist forces. The objective of the offensive focused on driving tsarist troops back across the Vistula River. During the ensuing battle and the resulting fifty-kilometer enemy retreat, the Russian Eighth Army suffered 70 percent casualties, and the effort succeeded in momentarily thwarting the threat of a tsarist invasion of Hungary. The Russians also had to abandon their efforts to invade Germany because of a serious threat to their right flank positions, a threat caused by their previous defeat and retreat. Consequently, Habsburg forces temporarily regained the initiative and extended their front to Gorlice, where major east-west railroads intersected and a successful Central Powers offensive ensued in early May 1915 after the 1915 Carpathian Winter War debacle.

The Russians had recently seized the critical Dukla Pass and constructed a defensive line, which extended to the Uzsok Pass. Habsburg post-battle reports emphasized the enormous losses sustained during recent battles and the extraordinary troop efforts expended under the harsh weather and terrain conditions. The troops suffered enormous hardships while fighting twenty-four-hour battles with no protective cover from enemy artillery fire and no regular meals and supplies. A continuing loss of active duty officers, noncommissioned officers, and soldiers led to declining battlefield effectiveness and slackened discipline in the ranks. The ever-present extreme exhaustion also accelerated troop apathy. War weariness took root, particularly in Vienna, and refugees continued to flee from Galicia, the Bukovina, and Poland into the Habsburg homeland.

The early December Limanova-Lapanov campaign, which had a major effect on Fortress Przemyśl, involved thirteen Habsburg infantry and four cavalry divisions (90,000 troops) attacking eleven to thirteen Russian infantry divisions (100,000–120,000 soldiers). On December 1, Habsburg eastern front forces totaled only 303,000 troops, having sacrificed almost a million soldiers since the initial August 1914 campaigns. On December 1 and 2, the Russians launched heavy forays at the Carpathian Mountain Beskid Pass, while the Habsburg Third Army, having sustained enormous casualties and teetering on the brink of exhaustion following its three-week November campaign, enjoyed a short rehabilitation period between December 2 and 7.

The Fourth Army’s XIV Corps, Group Roth, received reinforcements on December 1, and the German 47th Reserve Infantry Division, en route, arrived within a few days. The Fourth Army launched an offensive on December 3 with a strong right flank against the opposing tsarist Third Army’s southern flank forces.

But even at the onset of the ten-day Limanova-Lapanov campaign, the surviving soldiers of the Third Army had lost much of their will to fight. Technically, III Corps no longer existed after being reduced to less than half the number of an infantry division stand. IX Corps’ battle worthiness had also been decimated. Following eleven days of marching and thirty-five in combat, the army received an order to intervene in the ensuing Limanova-Lapanov battle. In their weakened physical condition, Third Army troops marched only fifteen kilometers a day toward the Fourth Army battlefield.

At Fortress Przemyśl, the worsening food shortage prompted the slaughter of thousands of horses, which increased the meat supply, added fat for cooking purposes, and helped alleviate the scarcity of straw and hay. With rationing and the slaughter of horses, estimates had the fortress’s food supplies lasting until early March. Troops foraged outside the fortress walls for frozen vegetables, while requisition commissions confiscated food from civilians on several occasions. Horse meat, originally a despised commodity, became a delicacy.2 Water had to be boiled because it was germ-infested due to the contamination of most wells. Bread portions, however, were reduced, as were vegetable and meat rations, including horse meat.

December 2 proved decisive for Third Army fortunes because the Russians removed at least three army corps from that army’s front, allowing the Third Army several days of rest and rehabilitation.3 The month heralded the commencement of significant Russian military activity at Fortress Przemyśl. On December 1, strong tsarist assaults renewed against the critical fortress Defensive District VI perimeter position at Na Gorach. General Kusmanek immediately launched a sortie against the enemy group’s left flank position that forced an enemy retreat. Nevertheless, the Russians continued their assaults against this sensitive forefield position.4

Fortress operations assumed greater significance with the commencement of the battle of Limanova-Lapanov on December 3. To bind the siege troops, General Kusmanek launched a sortie composed of eighteen and three-quarters infantry battalions and fourteen artillery batteries in coordination with the field army’s new offensive effort to liberate the citadel. Several smaller efforts were initiated from other sectors of the fortress as well.

Utilizing the cover of early morning fog on December 8, Russian troops overran the key Na Gorach blocking positions’ forward defensive lines. Meanwhile, General Kusmanek learned that a powerful Russian counteroffensive had forced Third Army Group Krautwald, entrusted with liberating the besieged citadel, to retreat. This disheartening report coincided with the setback at Na Gorach. Unbeknownst to the garrison troops, they had just experienced their next to last major sortie effort until the disastrous fortress breakthrough attempt on March 19, 1915, on the eve of its March 22 capitulation. Throughout this period, the distance separating the fortress and the field armies proved too great for field army success, and thus all attempts to liberate Fortress Przemyśl failed.

The Germans attempted to force the Russians behind the Vistula River in their Lodz campaign, while Habsburg forces received the minimum mission to bind opposing tsarist formations so that the Russians could not shift sizable troop numbers against the advancing German forces.

On December 3 and 4, tsarist troops cautiously approached Third Army positions along the ice- and snow-covered Carpathian Mountain ridgelines, particularly near the critical Dukla and Uzsok Passes. If the Russians had completely captured the entire Dukla and Uszok Pass territory, Habsburg forces would have lost their main defensive flank position. The Third Army, having suffered multiple defeats in the Carpathian Mountains in November, now lingered on the verge of a fatal collapse from battle exhaustion. The troops suffered from cholera and typhus in the snow- and ice-covered mountains 120 kilometers from the evolving Fourth Army battle.

Fourth Army Group Roth (XIV Corps) launched its major offensive effort, consisting of three infantry divisions, northward toward Limanova against advancing enemy forces on December 3. They targeted the Russians’ most vulnerable position: a sixty-kilometer gap between their Third and Eighth Armies that offered the greatest opportunity for Habsburg victory. Tsarist troops, however, successfully countered Group Roth’s offensive efforts. At the same time, a Habsburg defensive group, having encountered forward units of the Russian Eighth Army’s VIII and XXIV Corps, was forced back to Limanova, a small village located at the Russians’ flank position. A race commenced on both sides of the front in the general direction of the town of Neu Sandec, and Group Roth deployed small cavalry forces to probe the roads in that direction.

Habsburg Supreme Command ordered its weakened and exhausted ten-division-strong Third Army to prepare to support the new Fourth Army offensive, although it remained over one hundred kilometers from the main battlefield. Then, on December 4, the Russians perceived the danger posed by the Habsburg Fourth Army offensive operation and quickly began to reinforce their threatened flank positions. Russia, like Austria-Hungary, had to obtain a major battlefield success, otherwise Italy, Romania, and Bulgaria might be swayed to forgo their neutrality and enter the conflict on the opposing side, which both opponents mistakenly believed could decide the course of the war. On the Balkan front, the Serbian defeat of Habsburg forces followed an initial capture of Belgrade on December 2. News of the capture of Belgrade improved Habsburg civilian and army morale incredibly, sweeping aside the negativity caused by the November Carpathian Mountain battlefield events. Emperor Franz Joseph could now appear momentarily in public again. Belgrade had to be evacuated after a successful Serbian counterattack against the overextended Habsburg Sixth Army. This embarrassing defeat placed additional pressure on the tenuous situation at the Habsburg eastern front.

The three humiliating 1914 Serbian battlefield defeats—in August and September, but particularly the December fiasco—also seriously affected other future Habsburg military operations. The German Foreign Office and High Command urged General Conrad to participate in an allied offensive to conquer the Negotine (northeastern) sector of Serbia, which would restore Habsburg military honor and prestige while simultaneously opening a secure supply route to provide necessary ammunition and equipment to their new Turkish ally. A Balkan victory could also serve to convince Bulgaria to finally join the Central Powers; however, General Falkenhayn informed Conrad that he could not transfer additional German troops from the hotly contested western front for the proposed Habsburg operation. Conrad replied that he could not provide Habsburg soldiers for a Balkan campaign either, because his troops were currently tied down on the Russian front.5

General Falkenhayn’s eastern front strategy entailed hurling the Russians behind the San-Vistula River lines and reducing their offensive capabilities. Meanwhile, the German Ninth Army gained additional territory with its victory at Lodz against the ten-division-strong Russian Fifth Army. On the Habsburg front, the Third Army mission became to bind Russian Eighth Army troops, sever the last major tsarist supply and transportation artery behind its front, and block their potential retreat route. However, an unanticipated Russian counterattack briefly ended those plans and forced Third Army troops back into the mountains.

By December 4, the Habsburg Fourth Army’s Limanova-Lapanov operation had conquered considerable terrain. Group Roth advanced after shifting northward and initially encountering only weak tsarist cavalry forces, but then enemy resistance steadily increased. Meanwhile, unknown to either Conrad or Roth, the tsarist VIII and XXIV Corps began approaching the critical area of Neu Sandec, as their Third and Eighth Armies threatened Habsburg flank positions. By December 5, the only chance for a major military success was dependent upon the immediate reinforcement of Group Roth’s XIV Corps, because it lacked sufficient reserve formations. Since the enemy steadily received reinforcements, time was of the essence; the Fourth Army had to advance before additional large numbers of tsarist troops arrived at the front. Most immediately, Habsburg troops had to halt tsarist forces advancing toward Neu Sandec, which later became the distant Third Army’s new mission objective.6 Thus, General Conrad, on December 6, ordered the Third Army to commence forced marches from the west and northwest to reach the Fourth Army battle zone to prevent the consolidation of the tsarist Eighth Army’s VIII and XXIV Corps positions.

On that same day, Habsburg reconnaissance missions revealed that strong enemy forces were maneuvering toward Neu Sandec, which was a weakly held area. Concern mounted when deciphered Russian radio transmissions revealed details regarding the tsarist forces’ advance toward the town and the eighty-kilometer gap between the Habsburg Third and Fourth Armies and Group Roth’s attack forces. Thus reinforcements had to be deployed to Neu Sandec to secure the Fourth Army’s right flank positions. Strong tsarist resistance could now be felt all along the Fourth Army front.7 The enemy’s reinforcements and deployment of reserve forces endangered the Fourth Army main attack group and its entire operation. Additional units would be transferred from other Habsburg armies to this main battle area as quickly as possible as tsarist resistance halted all forward progress.

In the meantime, the newly arrived, full-strength 47th German Reserve Infantry Division had advanced twenty-five kilometers from its detraining area into the wooded Carpathian Mountain terrain, where vision proved severely restricted. Unfortunately, its troops were unaccustomed to winter mountain conditions and possessed no mountain equipment. Making matters worse, the early arrival of snow and ice proved detrimental to overall Habsburg offensive efforts. The 47th Reserve Infantry Division encountered delays in its marches to its assembly area, and then achieved only limited progress. The infantry division, on the eastern flank of the northern Habsburg offensive operation, opened a ten-mile gap between the Habsburg forces protecting New Sandec.

As early as November 1914, as noted, the Russian southwest front commander, General Ivanov, had issued secret instructions to prepare to invade Hungary. His particular attention focused on the significant problem of providing regular supply transport into the difficult Carpathian Mountain terrain, calculating that his preparations to launch an offensive could be completed within fourteen to eighteen days.8 General Ivanov pressed Stavka to reinforce his southwest front against a reputed German threat to his left flank positions, although there was no evidence of excessive German activity on that front or the threat of the liberation of Fortress Przemyśl. Ivanov’s pet project, the invasion of Hungary, required the conquest of the Carpathian Mountain front; he also fully recognized the great political significance of his proposed invasion while maintaining the siege of Fortress Przemyśl.

General Ivanov’s arguments convinced Stavka to transfer the XII Corps and five to six mountain artillery batteries from the German front to the southwest front, because regular field artillery proved ineffective on the mountainous winter terrain.

On December 6, 1914, thirteen Habsburg First Army divisions battled fourteen to fifteen Russian Ninth Army divisions in standing battle in the Pilica River area northwest of Fortress Kraków and the major Fourth Army operation. Russian Third Army troops maneuvered northeast of the fortress to the Vistula River, threatening Neu Sandec and attacking the German 47th Reserve Infantry Division. Other tsarist units from other fronts were deployed toward Neu Sandec.

Realizing their dangerous situation, the Russians deployed troops south of Fortress Kraków to attack Habsburg flank positions.9 This forced the Habsburg Fourth Army to shift from an attempt to encircle the enemy forces to a frontal assault toward Limanova and west of Bochnia. Meanwhile, on the East Prussian front, seven German Eighth Army divisions battled sixteen tsarist Tenth Army units on the northern flank of an attempted tsarist invasion of Silesia. The Russians retreated to the river line at Warsaw terminating the earlier major tsarist offensive against Germany.

Group Roth continued its assault. As tsarist advances continued to threaten Group Roth’s eastern flank positions and connections to its rear echelon area, the situation could not be ignored. Habsburg Supreme Command ordered that reinforcements be deployed to the Fourth Army to enable Group Roth to continue its attempt to encircle the opposing forces. Third Army units prepared to launch an attack against tsarist VIII Corps units in the critical area of Neu Sandec in an attempt to halt the Russian advance and achieve victory. As sickness, battle, and dwindling troop numbers weakened Fourth Army efforts, the Third Army’s intervention became an absolute necessity to assure obtaining an ultimate victory by preventing the Russian Eighth Army, deployed in the Carpathian Mountains, from intervening.10

A Russian counterattack in the area of Limanova endangered the success of the Fourth Army offensive as both sides desperately sought reinforcements to continue their offensive efforts. A tsarist VIII Corps attack pressed hard against Group Roth’s flank and rear connections. That serious threat increased the pressure for the Habsburg Third Army to intervene in the battle as soon as possible.11

As news began arriving of the unfortunate battle results on the Balkan front, Conrad worried that any further setbacks would sway Italy, Bulgaria, and Romania to intervene militarily against the Dual Monarchy. Conrad desperately sought to achieve a victory against the Russians, while Premier Istvan Tisza of Hungary demanded that enemy advances into Hungarian territory be halted. Conrad turned his attention to his Third Army to order it to intervene in the Fourth Army’s battle by deploying troops toward Neu Sandec.

The Russian Eighth Army pinned the Habsburg Third Army along the length of the Carpathian Mountains. The Russian Third Army slowly closed in on Kraków, the primary objective. Conrad recognized the possibility of turning the Russian Third Army’s flank as two Russian corps became increasingly exposed. Third Army units attacked Bartfeld, then proceeded to Neu Sandec. Group Roth attempted to prevent the Russians from pulling back to safety by shifting additional troops to its eastern flank position.

The situation became critical on December 7 when Russian Eighth Army units began to advance toward Habsburg Fourth Army positions at Limanova. The tsarist VIII Corps had already entered the battle, and the XXIV Corps also threatened to do so. By evening, the situation had become tense as the entire tsarist Third Army attacked Fourth Army positions. The Habsburg Third Army’s mission remained to ensure that the sixty-kilometer gap continued to separate tsarist Third and Eighth Army forces. Only minimal Fourth Army troop numbers were deployed at Limanova, where the enemy now advanced with strong forces. If Habsburg Third Army units rapidly reached the area of Neu Sandec as ordered, that could disrupt the tsarist corps’ rear echelon area, which threatened Fourth Army efforts. However, Third Army troops had to advance through difficult wooded terrain, encountering serious delays and problems as they attempted to move forward, while individual Landsturm troop units began to disintegrate because of their increasing casualty numbers.12 The lack of Habsburg reinforcements and inadequate frontline troop numbers intensified the crisis posed by the tsarist threat to Limanova. Heavy fighting raged for several days, extending from Lapanov north to Limanova.

On that same day, other Third Army (VII Corps) vanguard units on the other Carpathian Mountain front also attained the Dukla Pass, while X Corps entered Mezölaborcza on December 11 as they attempted to reach and liberate Fortress Przemyśl. General Kusmanek launched a powerful sortie on December 9 consisting of nineteen infantry battalions and fourteen artillery batteries to hinder any tsarist troop withdrawal of siege troops and confirm their troop numbers. The main sortie, cloaked by several smaller efforts, continued to bind Russian troops on the citadel’s southeastern perimeter flank on December 9 and 10.13

In an often-repeated scenario, Honvéd troops reached forward Russian positions but lacked sufficient troop numbers to pierce the strong enemy lines. Thus, additional offensive efforts proved fruitless because the Russians rapidly realigned their forces to neutralize any subsequent actions. The notorious inaccuracy of Habsburg artillery fire and accompanying short rounds had characterized the first siege, but at that time field commanders had blamed inadequate troop training for the failure. It must be mentioned that much of the fortress artillery was obsolete and that the gun tubes had begun to wear out. Nevertheless, on December 10, after two days of fierce fighting, the exhausted surviving soldiers withdrew into the fortress. Honvéd infantry regiment troops captured some prisoners of war and booty, but the effort proved inconsequential.

Spy paranoia, meanwhile, swept the fortress and resulted in widespread rumors of espionage within the citadel. Ruthenian peasants reportedly signaled Habsburg positions to the enemy by telephone, light signals, and messages placed in bottles and dropped in the San River, which merely increased the garrison’s spy hysteria and resulted in the shooting and hanging of hundreds of Ruthenians. The heavy, intermittent battle (and concomitant casualties) between December 9 and 28 significantly reduced the garrison’s offensive strength. General Kusmanek launched sorties on December 9, 10, and 13 and between December 15 and 18, producing heavy clashes before the fortress perimeter and particularly significant officer and veteran combat fortress troop casualties.

Meanwhile, Habsburg Third Army eastern flank forces advanced toward the fortress in an attempt to liberate it. Other Third Army units, in the meantime, had commenced marching over one hundred kilometers through snow-covered Carpathian Mountain passes and valleys to the Fourth Army battlefield. On December 8, those troops received orders to advance toward Neu Sandec as rapidly and with as many troops as possible. Meanwhile, between December 1 and 10, the Russians continued to transfer reinforcements from their north Vistula River and Carpathian Mountain theaters to the battle area. These additional enemy forces helped halt the Habsburg Fourth Army progress by launching a counterattack. The Russians regained the initiative as they smashed into Group Roth’s open flank position and pushed its troops back. The entire tsarist Third Army, reinforced by two corps, participated in the attack. In the meantime, the Fourth Army’s offensive had shifted from the attempted envelopment of tsarist forces, as mentioned, to a frontal battle in the Limanova area. Russian VIII Corps troops continued to attack the Fourth Army’s flank and rearward connections along the Neu Sandec railroad stretch.

Some Third Army troops marched to within a mere twenty kilometers of Neu Sandec, while its IX Corps made its way to the major transportation center at Gorlice. A Fourth Army force of five infantry and one cavalry division defended the high ground south and north of Limanova against the tsarist VIII Corps attack, having to utilize nonbattle troops for combat to continue the fight. As a result of accelerating casualties, its division numbers had shrunk from 12,000–15,000 soldiers to only 2,000–3,000, while the Third Army’s average division numbers dropped to only 2,000 troops. Its 3rd Infantry Division, for example, had been reduced to 900 troops by December 10.14

Third Army right flank Group Krautwald forces, still attempting to liberate Fortress Przemyśl, advanced to within fifty kilometers of the citadel while garrison troops in forward perimeter positions listened to the sounds of that battle. The mentioned fortress sortie objective became to bind tsarist troops from interfering with Group Krautwald’s effort.15

As air reconnaissance efforts were interrupted by inclement weather conditions, they failed to discover significant tsarist troop movements. Meanwhile, the Fourth Army crisis intensified as the Russians increased pressure on their eastern and rear flank positions from the south. A tsarist counteroffensive on the northern front threatened to break through Fourth Army lines and forced Habsburg troops onto the defensive, while the poor handling of railroad traffic continued to hamper the transportation of reinforcements. The Third Army’s Group Szurmay 38th Honvéd Infantry Division and a combined division advanced toward Neu Sandec, finally initiating its decisive appearance on the Fourth Army’s battlefield, striking tsarist vanguard units along a broad front. The next day, Habsburg Third Army troops compelled the enemy to retreat by driving decisively through the gap between the two enemy armies, consummating the Limanova-Lapanov victory.

In the meantime, the First Army’s XVIII Corps continued its delayed rail transport to the Third Army eastern flank area to reinforce it and provide sufficient impulse to the Third Army attempt to liberate Fortress Przemyśl, but the low-capacity mountain railroad lines seriously retarded arrival timetables. Third Army detachments fanned northward toward the strategically important area encompassing Dukla-Zmigrod-Gorlice on December 11. The remainder of the Third Army troops had resolutely marched toward the critical Neu Sandec region to positively affect the Fourth Army’s Limanova-Lapanov battle.

The Russian assaults against the German 47th Reserve Infantry Division had, meanwhile, failed. As the Third Army continued its advance, it encountered only Russian rearguard units and thus could shift its left flank units toward Neu Sandec. To support Fourth Army efforts, the 106th Landsturm Infantry Division launched a sortie from Fortress Kraków to bind tsarist troops deployed at the citadel.16

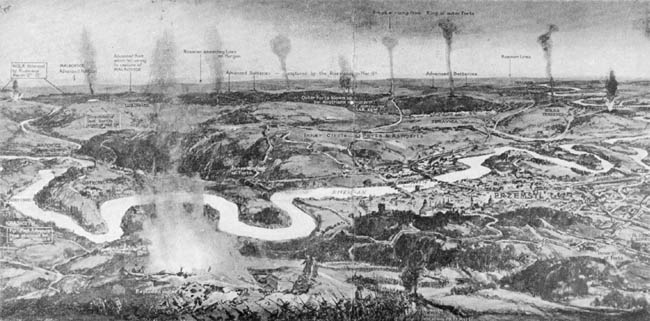

Map 5.1. Fortress Przemyśl, December 1914.

On December 11, Third Army’s IX Corps had attained the area of Gorlice, severing the important enemy’s east-west transportation link and forcing their troops to begin to withdraw, which proved significant for the Limanova-Lapanov operation’s success. The Third Army’s advance placed it in the gap between the Russian Third and Eighth Armies’ southern flank and rearward connections. This prevented the tsarist XXIV corps from intervening in the main battle and ultimately forced the Russian retreat. The victory at Limanova-Lapanov received invaluable aid from the full-strength German 47th Reserve Infantry Division, which possessed more troop numbers than several participating Habsburg divisions combined.

The turning point in the fight for Limanova-Lapanov occurred on December 12, when Habsburg Third Army units decisively intervened in the Fourth Army’s battle, forcing the tsarist VIII Corps from the Neu Sandec area while its IX Corps pushed the enemy’s XXIV Corps rearward, advancing into Neu Sandec and forcing the tsarist retreat.

On the Carpathian Mountain front, the Third Army’s VII Corps seized the Uzsok Pass on December 17; thus, Group Krautwald on the army’s eastern flank advanced to the east in an attempt to sever the key enemy railroad supply line and retreat route at Lisko-Sanok, then on to attain the San River lines and liberate Fortress Przemyśl.17 However, all subsequent Habsburg December efforts to liberate the fortress proved futile. Excessive casualties and the lack of reserve formations to replenish depleted Third Army ranks proved decisive in preventing the forcing of tsarist troops back across the Vistula River. In addition, the overutilization of Habsburg railroads seriously retarded the transport of troops and supplies, resulting in traffic chaos.18

The tsarist objective, on the other hand, entailed occupying and fortifying key Carpathian Mountain crossings to secure the Russian southwest flank position, an absolute necessity before attempting to launch another invasion of Germany. General Ivanov concentrated his forces around the Mezölaborcz railroad and communications center, soon to be the scene of major battle during the first Carpathian Mountain winter offensive campaign in late January and early February 1915.

Fortunes fluctuated daily during the battle, but it ultimately produced the first significant Dual Monarchy battlefield victory against Russia. Nevertheless, it came at a heavy cost, and Habsburg officers had to counter the increasing apathy that permeated their troop ranks. Poor troop morale made it difficult to maintain discipline in the ranks during the campaign. The majority of the exhausted troops participated in almost constant battle, which seriously hindered the rapid pursuit of enemy forces that Conrad ordered following the significant battlefield victory.

Habsburg forces defeated the numerically superior tsarist units by skillfully utilizing maneuver tactics and their interior lines to their advantage. General Conrad also succeeded in momentarily overcoming the increasing criticism of his command leadership.19 The Third Army, in the interim, attempted to achieve a major victory on its right flank by inserting the in-transport X and XVIII Corps to pursue and encircle the retreating enemy forces in the area close to Fortress Przemyśl. Ice-covered roads, however, severely retarded the transport of those troops. The Russians, meanwhile, deployed strong forces to protect their threatened Third and Eighth Army inner flank positions. Excessive Habsburg troop exhaustion and excellent Russian retrograde movements prevented major tsarist territorial losses and seriously hindered Habsburg efforts to effectively pursue defeated enemy troops.

Allied Austro-Hungarian and German forces had finally halted the heretofore unstoppable Russian steamroller pressing into Galicia. They prevented the enemy from successfully traversing the Carpathian Mountains to invade Hungary and forced them to abandon plans to seek a major military decision against the Germans because of the sudden threat to their southern flank positions on the southwest front. The threat to Fortress Kraków ended, and the Habsburg front momentarily had stabilized.

During the decisive phase of the battle, Army Group Pflanzer-Baltin protected the extreme Habsburg eastern flank position along the major ridgelines in the Carpathian Mountains against Russian units almost double its size. In early December, the Army Group had been forced to extend its front lines to close the gap in its lines resulting from the Third Army’s westward deployment shift, caused by the redeployment of some Second Army units to the Polish front. The stubborn Army Group commander steadfastly refused to surrender any of his several-hundred-kilometer front, now extending from southern Galicia to the Bukovina.

On the German front, the Russian First, Second, and Fifth Armies now defended Warsaw, the transportation and depot center along the right Vistula River bank area. On their southwest front the tsarist armies retreated along the Vistula River to prepare to launch new military operations. The tsarist Eighth Army’s slow Carpathian Mountain retrograde movement delayed the Habsburg Third Army’s pursuit of the enemy’s retreating forces around Fortress Przemyśl by destroying the San River bridges as they withdrew. The Eleventh Army maintained its siege of Fortress Przemyśl and prevented garrison troops from advancing to the Jaroslau area (north of the fortress) and Third Army eastern flank forces from liberating the citadel. Habsburg Third Army forces desperately, but unsuccessfully, attempted to attain the critical Lisko-Sanok railroad junctions that would remain the Habsburg operational objectives throughout the 1915 Carpathian Mountain winter campaign. The Third Army lacked sufficient troop numbers to reach Jaroslau, Przemyśl, and Chyrov. Tsarist troops remained ensconced behind their strong defensive positions before the San River in the area of Fortress Przemyśl.

At the same time, the tsarist 19th Infantry Division, redeployed from the Fortress Przemyśl siege front in mid-December, was replaced by three reserve infantry divisions. Due to foggy conditions, Habsburg air reconnaissance failed to detect not only this movement but other major enemy activities as well. Then, a fortress air reconnaissance mission finally spotted large Russian troop and supply columns moving eastward, leading General Conrad to assume that any present tsarist military action served merely to gain time because of their recent defeat.20 Conrad planned to capitalize on the Limanova-Lapanov campaign by launching a relentless pursuit action to encircle retreating enemy soldiers, mainly with his Third Army eastern flank units, although his battle-weary troops continued to desperately require rest and rehabilitation. Meanwhile, the Russians assembled strong forces in preparation to commence their own major offensive operation, which rapidly stifled all further Habsburg offensive efforts.

On December 14, Fortress Przemyśl garrison units cooperated with Third Army right flank Group Krautwald’s attempts to liberate the bulwark. In the meantime, tsarist units had retreated to east of the Vistula River. The entire Russian front commenced a general retrograde movement. The tsarist troops destroyed all bridges and established individual vanguard position resistance. The Habsburg pursuit continued on December 15 and 16. The Habsburg Third and Fourth Armies encountered tenacious Russian rearguard defensive efforts, which attempted to delay the pursuing Habsburg troops as long as possible in the area of the Biala and Dunajec Rivers. The Third Army’s mission, after advancing, entailed disrupting the Carpathian railroads in the latter area. In addition, the question of negotiating a separate peace with Russia arose, but St. Petersburg vetoed such efforts as the Entente powers signed a pact agreeing not to negotiate a separate peace with the Central Powers.21 Rumors spread on December 14 that the Germans sought a separate peace with Russia. Conrad approached Leopold von Berchtold in opposition of such a notion.22 General Falkenhayn had come to the conclusion that the Central Powers could not defeat the combined Entente forces.23

In the interim, on December 14, Habsburg field armies had renewed their offensive, and Third Army flank Group Krautwald forces pursued the enemy toward the fortress through the Dukla Pass to Sanok (about fifty kilometers from the bulwark). This force threatened the rear echelon connections of the tsarist front, providing perhaps the opportunity for a decisive advance to liberate the citadel. Group Krautwald encountered and battled three Russian divisions. As a result, Third Army units had to retreat to their defensive lines, encountering serious attacks on their rearguard positions as they did. The fortress sortie launched on December 15 expanded to between twenty-three and twenty-five infantry battalions, fifteen artillery batteries, and eight and one-half cavalry squadrons. These forces advanced toward Bircza and Krzywcza, which initiated the four-day battle between December 15 and December 18. Initially, the operation produced a string of uninterrupted victories, hurling enemy troops back from numerous forward strongly fortified tsarist defensive lines. But when the fortress offensive units reached strong Russian forward defensive positions, the attackers lacked sufficient troop numbers to breach the enemy’s main well-prepared defensive lines while receiving neither sufficient nor effective artillery support. The terrain also favored the tsarist forces, which regrouped and neutralized any further Habsburg assaults.

The Third Army received orders to renew its right flank offensive efforts on December 15, but it immediately encountered strong tsarist defensive measures and effective artillery fire. The San River gave the Third Army’s northern flank some protection for its advance.24 The Third Army’s objective encompassed attaining the areas of Sanok-Krosno-Jaslo, but its intended eastern offensive flank units required the previously mentioned X and XVIII Corps reinforcements to enable it to advance further toward Jaroslau- Przemyśl-Chyrov to liberate the fortress. General Conrad desired to force the San River crossings and then drive east to liberate Fortress Przemyśl, but he feared that the Russians would be able to retreat behind the river undisturbed. Group Krautwald meanwhile attacked toward Lisko, but those efforts failed. The Habsburg Fourth Army pursued the fleeing tsarist troops along the entire course of the San River, but the enemy destroyed all the bridges to delay any forward pursuit.

Unrelenting inclement weather and extremely poor road conditions caused perpetual delays in Habsburg troop and supply column movement. The Russians could more easily replace their casualties and thus speedily recovered from the German front Lodz and Habsburg Limanova-Lapanov battles. Sickness, extraordinary physical activity, and battle losses steadily decreased Habsburg numbers, while the troops’ physical condition, combined with the lack of equipment, artillery shells, and food, took an increasingly enormous toll. The troops still lacked winter uniforms.

The month of December also witnessed the largest fortress sorties being launched. One operation succeeded in advancing eighteen kilometers into tsarist defensive positions, but the subsequent battle losses strongly reduced the bulwark’s offensive capabilities. Troop morale plunged as the possibility of liberation appeared to vanish by the end of 1914. From then on, the fortress received weeklong enemy artillery barrages on a regular basis.

Fortress Przemyśl garrison troops, however, still had to cooperate with the Third Army attempts to liberate the bulwark by launching a major sortie, which briefly raised the morale of the citadel because military personnel and civilians now anticipated the rapid liberation of the fortress.25 During the December 15 fortress action, garrison troops had to traverse rugged and forested mountain terrain, including a long, torturous 500-meter-high ravine, under poor visibility conditions.

The failure of Third Army troops to advance as anticipated decided the fate of the fortress sortie. For the garrison sortie to have had any chance of success, during both sieges, field army troops had to advance to the proximity of the fortress. Fortress troops had just disregarded their serious casualties in the hope that the fortress would soon be liberated. Garrison soldiers realized that they lacked the necessary troop numbers to achieve a major military success, which in turn depended on achieving surprise and launching a rapid offensive to deny the enemy valuable time to effectively react and initiate effective counteractions. Success was closely correlated with the Third Army’s proximity to the fortress, because sortie troops anticipated a rapid tsarist counterattack.

Map 5.2. Fortress Przemyśl sorties.

However, the three-day drama, as with all sortie efforts, produced the same results: some conquered enemy terrain gained with much human sacrifice soon had to be surrendered. A hasty retreat inevitably followed, with the concomitant loss of garrison troop morale. The attack commenced at 5:00 a.m. on December 15 with nineteen infantry battalions and twelve artillery batteries toward the high terrain at Cisova.

Third Army command radioed the fortress to inform them that the Russians had begun to retreat. Thus, they requested that garrison units bind enemy troops at its front and launch a sortie to join the Habsburg forces halfway to cooperate in hurling enemy forces behind the San River, or, at a minimum, neutralize their present efforts. By December 17, enemy resistance had solidified considerably, and Fortress Przemyśl garrison sortie setbacks had become more serious. Grave difficulties continued during attempts to transport artillery and supply trains on the miserable mountain routes. The fortress troops could not reach the Third Army lines once its lead forces had been defeated, eliminating a major opportunity to liberate the fortress. This news destroyed any lingering hope that the bulwark could be liberated and struck a serious blow to the inhabitants’ morale.

Fortress casualties between December 15 and 18 included a thousand dead and wounded, and 232 additional prisoners of war were captured. Three thousand casualties were sustained between December 15 and 21, mostly in the fighting at Na Gorach. Meanwhile, thousands of corpses covered the battlefield.26

As early as December 16, the Third Army encountered stubborn enemy resistance on the main battlefield. The Russians masterfully utilized their inner line advantage during their retreat and deployed strong forces against the Third Army right flank positions before the Habsburg reinforcements (X and XVIII Corps) could arrive. As weather conditions deteriorated, the extreme eastern flank X Corps had to halt enemy progress and repulse tsarist thrusts near Lisko. Army Group Pflanzer-Baltin received orders to prepare a twenty-battalion, nine-battery assault force against the strategic Uzsok Pass on December 20.

The fatal combination of insufficient troop numbers, overextended front lines, unfavorable weather conditions, and impassable terrain made it difficult to defend new positions once the exhausted Habsburg troops’ forward progress ended and the Russians launched a counterattack. The continuing lack of reserves also did not bode well for battlefield success. Sickness, excessive physical exertion, and large numbers lost as prisoners of war or and stragglers removed many troops from action by mid-December.

Thus, by December 18, after the failure of the four-day fortress sortie in the area between Cisova and Bircza, the Habsburg effort initially repulsed forward enemy positions, captured several machine guns, and seized control of the Bircza roads south of Cisova. Neighboring units, however, could not advance rapidly enough, so the Honvéds ultimately had to sacrifice the captured high terrain.

The entire Habsburg Third Army quickly terminated its pursuit efforts between December 18 and 20, while the seemingly endless supply of Russian reinforcements enabled the enemy to launch a series of counteroffensives that ruptured the weak and fragile Habsburg defensive positions anywhere on the front they selected. Tsarist occupation of key Carpathian Mountain ridges provided the necessary security for their troops besieging Fortress Przemyśl, while it also offered an opportunity to soon launch a decisive offensive into the heartland of Hungary. The enemy also enjoyed the major advantage of shorter, more direct railroad and road transport routes for its supplies and reinforcements, as Habsburg units were ensconced in the higher mountain terrain; thus, their reinforcements had to be rail transported over a much wider area, extending from Fortress Kraków to Mezölaborcz and Takczany. Dual Monarchy troops then had to march considerable distances over rugged mountain terrain to attain their deployment area.

While the Habsburg Fourth Army maintained its positions along the confluence of the Dunajec and Vistula Rivers, Third Army troops surrendered several crucial mountain passes to irresistible Russian frontal assaults and then retreated twenty kilometers on December 18. A new defensive line ten to twelve kilometers south of the lost passes was established between the mountain ridges and the important Ung valley. Encountering particularly strong Fourth Army enemy defensive positions, its commander determined to transfer numerous infantry divisions to the Third Army rather than launch an attack himself, a practice that would continue throughout the 1915 Carpathian Winter War campaign.

During the latter half of December, the military initiative at the fortress and on the Carpathian Mountain battlefield reverted to Russian favor as Habsburg military setbacks continued unabated. Enemy troops hurled Third Army units from the Carpathian Mountain forelands back to several major ridges with enormous losses.

By December 19, it became evident that the precarious Third Army eastern flank forces needed to be strengthened with the in-transit X and XVIII Corps. An attempt to encircle the opposing tsarist forces and liberate Fortress Przemyśl required significantly more troop numbers. The Third Army had the mission to bind the opposing Russian Third and Eighth Army troops until the arrival of the two reinforcing corps. Conrad continued to attempt to convince General Falkenhayn that military success against Russia would lead to the defeat of France and Serbia. Conrad, however, also recognized that without German assistance he would be unable to extend the Habsburg front east of Fortress Przemyśl, which made his overall chances of success minimal at best. With tragic consequences for the Austro-Hungarian army, General Conrad’s strategic planning became based primarily on liberating the fortress. This would have catastrophic results and nearly annihilate the Habsburg army during the 1915 Carpathian Mountain Winter War campaign.

On December 17, an alarming internal fortress report indicated that the fortress could sustain itself only until early January 1915 because of the rapidly depleting food supplies.27 General Kusmanek, considering the calculations too conservative, established a commission of inquiry to further investigate the matter. As the situation became increasingly desperate, widespread corruption spread throughout the bulwark.

The Germans were determined to continue their operation in the middle Vistula River area, thus General Falkenhayn invited General Conrad to discuss further allied military objectives with him.28 Conrad finally realized that his exhausted troops, now at their breaking point, had been “pumped dry.” During the past five months, Habsburg troops had launched three offensives against the Russians but had been forced to retreat after the first two operations while sustaining almost a million casualties. During the ensuing retrograde movements, the field armies abandoned enormous amounts of irreplaceable equipment and food supplies. On December 21, Conrad reported to the Emperor’s Military Chancellery that “the best officers and non-commissioned officers had died or been removed from service,” as well as the professional corps of the rank-and-file troops. He also described Habsburg reserve or replacement troops as “being of poor quality and partly young, partly older men.” The 1914 eastern front campaign had almost eliminated the Habsburg army as a viable fighting force. The final casualty toll included 189,000 dead, 500,000 wounded, and 280,000 taken as prisoners of war. Officer casualties alone reached 26,500. In December 1914, the Dual Monarchy could deploy only 303,000 combatants against the numerically superior tsarist enemy, but few had the capability to liberate Fortress Przemyśl. German liaison observers at Habsburg headquarters noted that General Conrad had lost faith in his own troops and that a dangerous fatalism now permeated Habsburg Supreme Command. Conrad also complained about his secret enemies, the Germans and the German emperor, whom he described as a comedian.29 Conrad resented the German expressions of superiority over his troops, their snide comments, and the fact that they represented the stronger ally.

On December 20, General Kusmanek launched another sortie toward the Na Gorach ridge to press enemy troops back, while Defensive District VIII launched a distraction effort to cloak the location of the main action.30 Meanwhile, on December 22, the sortie troops retreated into the fortress.

As battle raged before the Fortress Przemyśl perimeter, General Kusmanek convened the previously mentioned commission of inquiry on December 20 to investigate the dwindling fortress food supply. The next day, the fortress quartermaster reported that the horse fodder reserve would last only until January 1915, but when the commission results were completed on December 28, the new calculations extended the supply of horse feed until February 18 and fodder until March 7.31 The commission demanded that ten thousand horses be immediately slaughtered to provide additional sustenance for the starving garrison troops. Habsburg Supreme Command accepted the commission’s findings but continued to be alarmed by exaggerated fortress claims. Subsequent reports extended food supplies until March 23. However, these findings proved misleading, as the commission ignored calculations based on fewer garrison troops, horses, and civilian numbers than the fortress actually housed.

On the main battlefield, Habsburg Supreme Command remained completely unaware of whether Stavka now intended to order a retreat behind the San River or, conversely, to launch an offensive. The Russians could not immediately launch an attack to protect their retreating troops, but the windy, icy mountain terrain also retarded any rapid Habsburg pursuit of them. The pursuing troops’ exhaustion and excellent tsarist retreat tactics prevented a disaster for the defeated enemy forces.

On December 20, Conrad announced directions for continuing Habsburg military operations, returning to his 1914 concept of a double envelopment launched from East Prussia and Galicia. Third Army eastern flank forces must liberate Fortress Przemyśl and also create a dependable defensive security system for the Carpathian Mountains. The other Habsburg armies must maintain their earlier positions and attack the enemy only if it attempted to transfer forces to another front. However, in the meantime, the enemy amassed enormous troop numbers at the endangered Third Army right flank area; this increased tsarist presence ultimately terminated any attempts to advance or to liberate Fortress Przemyśl.

Between December 20 and 24, the Russians launched a decisive counteroffensive along the entire Galician front. Utilizing the cover of heavy snowfall and fog, the Russians initiated fierce battle and seized the major Carpathian Mountain ridgelines, neutralizing any potential Habsburg military threat from that direction. The tsarist objective remained to cross the easily accessible Dukla Pass to traverse the remaining Carpathian Mountain ridges to invade Hungary and to capture Budapest. On December 20, the vulnerable Habsburg nine-division army crumbled under the twelve-division Russian counterattack. Continued Russian military successes also raised the specter of neutral Italy and Romania entering the war against the Central Powers. When Habsburg Third Army units had to retreat into the mountains, this also forced the neighboring Fourth Army right flank units to initiate their own retrograde movement to the Dunajec River. Habsburg military operations south of the Vistula River had reached their turning point. All Habsburg counterattacks to the enemy assaults launched between December 20 and 22 failed, but Third Army command nevertheless continued to plan further offensive efforts, hoping that once X and XVIII Corps troops arrived at its right flank deployment areas, it could turn the tide of the battle in their favor.32 The major Russian counterstroke, however, ultimately neutralized those efforts.

The Habsburg field army now faced a seemingly insurmountable obstacle with its rapidly declining troop numbers. For example, III Corps’ three divisions now consisted of only 10,200 men, while IX Corps’ numbers were equally low.33 On December 22, the Third Army’s VII Corps was suddenly faced with encirclement and defeat at the Dukla Pass, because it could not resist the major enemy assault. Its present positions had to be maintained to enable Third Army Command to insert the still en route X and XVIII Corps at the designated army’s right flank to relaunch its offensive. Thus, the unexpected gap that opened between III and VII Corps positions created a dangerous situation that portended disaster for any future Habsburg offensive efforts.

When Habsburg XVIII and X Corps units finally began arriving in strength, VII Corps had been hurled out of the Dukla Pass, also prompting the retreat of the neighboring III Corps. The Russians consistently battered III and VII Corps positions, VII Corps bearing the brunt of their incessant attacks. The few corps reserves could not turn the tide of battle, forcing VII Corps to retreat to the high terrain south and southeast of the Dukla Pass, removing the cornerstone positions vital for the arriving X Corps deployment. The limited capacity and stoppages on the small-gauge mountain railroads had seriously delayed the troops’ arrival. The undaunted tsarist Eighth Army continued to smash forward, while other attacks battered Habsburg positions between the Biala and Dunajec Rivers to bind those forces and prevent reinforcements being transferred to the battered Third Army.

Then, on December 22, another major enemy assault threatened to breach the front lines between the Third and Fourth Armies’ inner flanks. Their drastically diminishing troop stands raised the question whether either army could halt enemy pressure until the X and XVIII Corps had been fully deployed. Army Group Pflanzer-Baltin received orders to retake the Uzsok Pass to provide some protection for the endangered Third Army flank positions. As the tsarist advance swept forward through December 23, the beleaguered Habsburg troops were again ordered to maintain their lines until the main XVIII Corps units arrived, which could not be anticipated until December 26. However, on December 24, the Russians again smashed into the reeling Habsburg III and VII Corps positions. The dangerous combination of overextended front lines, diminishing troop stands, severe weather, and difficult terrain again created perilous gaps in the Habsburg defensive lines. Battle fatigue had also become universal along the entire Habsburg front, preventing the troops from mustering any serious resistance to enemy offensive efforts at the mountain crossing sites.

Third Army right flank offensive Group Krautwald had initially gained considerable territory, but only because the enemy had concentrated its main military efforts against the VII Corps positions at the critical Dukla Pass. General Josef Freiherr Krautwald attempted to continue his offensive efforts until December 24, but when tsarist troops broke into the VII Corps east flank positions, his group and ultimately the entire Habsburg front had to retreat. Belatedly inserting the late-arriving X Corps units into Third Army right flank positions proved ineffective because the Russians unleashed another surprise attack, abetted by inclement weather conditions, which forced further Habsburg retreat.

At Fortress Przemyśl, Christmas was described as the most tragic event on the entire Habsburg eastern front during the holiday season. The future seemed hopeless for garrison troops as they contemplated perpetual battle followed by death or capture.34 By December 23, it had become obvious that the Russians had launched a decisive offensive between the San and Vistula Rivers, but Habsburg Supreme Command lacked the necessary troop numbers to halt the tsarist army.

By December 21, fortress inhabitants had already begun preparations for the Christmas holidays. For example, the hospitals detailed men to go into the woods outside the fortress perimeter to cut down and bring trees back to cheer up the patients.35 On Christmas Eve, a group of the garrison perimeter troops, despite the deep snow, kneeled outside a small chapel to pray. The bulwark garrison unexpectedly enjoyed a brief reprieve as tsarist artillery lay silent until the New Year. However, on December 23, the Russians briefly attempted to seize the forefield positions at Na Gorach–Batycze. Here, undernourished and exhausted perimeter troops remained dangerously close to enemy positions and continued to suffer from the fluctuating bitter winter weather conditions without cover or warmth. Worse, these forward positions lacked adequate protection from enemy artillery fire, and the benumbed soldiers had to perform around-the-clock repair work on them.

On Christmas morning, the fortress’s Defensive District VII artillery observers noticed that a large table had been placed outside the fortress walls. Returning garrison patrols also brought back baskets of white bread, other food items, and tobacco. During the holiday season, Russian pilots also halted the bombing of the fortress area.36

On Christmas Eve at another location, Russian troops placed a large proclamation on the barbed wire emplacements. At another forefield observation post two Russian officers, displaying a white flag, proclaimed their Christmas wishes, while some tsarist troops presented bread and tobacco to fortress soldiers. Often forward garrison troops found Russian cigarettes left close to their positions. Troops from both sides had developed a form of camaraderie, oftentimes addressing each other by name across the front lines.37 Neither side fired artillery shells, and gunshots could rarely be heard as both sides honored the unofficial pact until after Christmas. The Russians naturally anticipated the same favor during their Orthodox holidays in two weeks.38

On Christmas Day, the Habsburg field armies commenced a general retreat to a shorter defensive line to await replacement troops and sorely needed artillery shells. The Fourth Army’s southern flank positions had to be moved back to Gorlice, sustaining heavy losses in the process. Group Pflanzer-Baltin’s forces seized the Uzsok Pass after a four-day battle, but the military setbacks at the Dukla Pass and elsewhere rendered it a hollow victory. The Russians again broke through Third Army lines in the Dukla Pass area, creating renewed crisis. The impossibly muddy retreat routes pushed the troops to the brink of their physical and emotional capabilities.39

Between December 25 and December 27, the enemy seized the key Beskid Mountain roads and continued their advances, forcing the Third Army further back to the main Carpathian Mountain ridgelines. The continuing chronic lack of reserve forces aggravated the seriously declining troop numbers and created large gaps between defensive positions. An ammunition shortage exacerbated the already dire military situation. Third Army troops continued to endure brutal weather and terrain conditions, while losing irreplaceable numbers of troops, horses, and necessary supplies and equipment during their retrograde maneuvers.

Stronger defensive measures became necessary to halt further enemy egress between Third and Fourth Army inner flank positions, where Habsburg forces sustained heavy losses when forced back to the Gorlice area. With his armies again on the verge of collapse, General Conrad urgently appealed for immediate German military assistance to help maintain his tenuous mountain front, reminding General Falkenhayn of the danger of the neutral powers intervening in the war because of the unfavorable eastern front military situation.

The Russians, meanwhile, replenished their ranks in preparation for renewed offensive operations against the hapless Habsburg Third Army. Utilizing the heavy rain and dense fog conditions to their tactical advantage, the enemy advanced along the vital roadways toward Baligrod, a major Habsburg objective during the forthcoming 1915 Carpathian Mountain Winter War campaign. On December 27, tsarist troops successfully ruptured VII Corps 17th Infantry Division’s positions to clear that important high terrain. Given the unrelenting numerical superiority of the enemy forces, the Habsburg ammunition shortage further worsened the critical military crisis. Defending their positions proved to be a monumental task for the weary Habsburg soldiers.

A December 26 Habsburg Supreme Command radio dispatch to General Kusmanek ordered him to launch a sortie to support Third Army attempts to advance. On the next day, he hurled twenty and one-half battalions, two cavalry squadrons, and fifteen artillery batteries against enemy siege positions, but, unbeknownst to Kusmanek, the delayed arrival of the XVIII Corps forced the Third Army to cancel its operation. The fortress order to commence the sortie, however, had already been issued and the operation launched against reinforced tsarist defensive positions. Again, the weary garrison attackers succeeded in reaching the enemy’s well-prepared siege lines but could not penetrate them. Then came the customary enemy counterattacks, defeat, and enormous loss of sortie troop morale. The pointless venture ended the next day. With such successive operations, the garrison troops’ poor physical condition, along with intense food rationing, left the troops increasingly unable to perform their duties adequately.

Enemy corpses lying before the fortress walls could not be buried because of the tenuous military situation. Lack of sleep, insufficient nourishment, and the harsh winter conditions only accelerated the garrison troops’ deteriorating condition. Some soldiers simply collapsed and died, while others deserted to the enemy. Battle reports emphasized the extraordinarily strenuous troop efforts under the horrendous conditions.40

Garrison troops had been in constant battle for twelve days with little pause during the fortress efforts. Troop numbers, particularly those of officer rank, had been greatly reduced, which negatively affected military discipline, especially within the inadequately trained Ersatz troops.41 The slaughter of horses also further reduced mobility and increased troop duties, which negatively affected soldier morale as well, since the troops now had to perform functions that the horses had carried out earlier.

The loss of the province of Galicia in December signified a major reduction in grain supplies, oil, horses, and army recruits for the Dual Monarchy; the loss of the Bukovina province raised concern about Romania entering the war against Austria-Hungary. In the interim, Habsburg field army troops retreated further behind the main Carpathian Mountain ridges to recover and replace the significant troop losses, while simultaneously attempting to halt the enemy advances into the region and a possibly decisive invasion onto the Hungarian plains. The Russians continued to starve Fortress Przemyśl into submission, not anticipating any serious threat to their siege forces from the increasingly weakened garrison troop contingents.

The late December tsarist military successes were tempered only by the winter weather conditions, which delayed their efforts. Meanwhile, a dangerous twenty-kilometer gap between the Dual Monarchy’s Third and Fourth Army’s inner flanks had to be sealed, but because of inadequate troop numbers, this proved impossible. The Fourth Army’s problems increased because of its now endangered southern flank positions, where, for example, the 10th and the arriving 13th Infantry Divisions numbered only six hundred rifles.

The military situation deteriorated further between December 28 and 31 when a Third Army withdrawal along both sides of the important narrow-gauge Lupkov Pass railway became necessary after the Russians attacked along the entire front. On December 28, battle raged at the Dukla, Uzsok and Lupkov Passes and other critically important Carpathian Mountain areas, where the ill-fated 1915 Carpathian Winter War offensives would soon commence. The Habsburg military situation had deteriorated so drastically that General Conrad contemplated redeploying his Second Army to the endangered Carpathian Mountain front from the German Silesian theater.42 Also, on December 28, a sortie emanated from Defensive District VIII. When the Third Army offensive collapsed, Habsburg Supreme Command ordered a halt to the latest citadel sortie.43

During the period December 9–28, significant portions of the Fortress Przemyśl garrison fought outside the citadel against tsarist siege troops. In the process, some of the best fortress troops continued to become casualties, which greatly reduced the bulwark troops’ fighting capacities. The lack of sufficient food, along with severe rationing, further negatively affected the health of man and beast. The slaughter of ten thousand horses provided temporary sustenance, but in the process the garrison troops lost much of their mobility and physical capabilities. Running out of artillery shells merely exacerbated the situation.

During the night of December 30, the Russians attacked several Third and Fourth Army front positions, forcing further retreat. As the year wound down, mutual exhaustion forced a brief battle pause on the Carpathian Mountain front.44

By late December 1914, the tsarist general Ivanov believed that he could decisively defeat his seriously weakened enemy because of its increasingly worsening critical military situation. He envisioned launching a decisive war-ending offensive into Hungary. General Conrad, after ensuring that the Habsburg army had somewhat recovered and replaced some of its enormous casualties, determined to initiate an offensive operation in the Carpathian Mountains in early 1915. He ignored the numerous valid arguments against launching a winter mountain campaign in such rugged terrain and horrendous inclement weather conditions. Launching an attack on the ice- and snow-covered mountain slopes and ridges with a skeleton or Miliz army would be a fateful gamble.

At the end of the year in Fortress Przemyśl, the combination of mass troop and animal starvation and worsening weather conditions had diminished garrison resistance to disease. Cases of petty crime, embezzlement, and robbery increased. Harsh penalties no longer had any major effect on halting crime, since military authorities themselves had become complicit in accelerating the corruption. Reports surfaced that wounded patients received little medical attention and that many starved to death. Wounded troop numbers had increased enormously with the launching of the December sorties. Morale in the hospital wards remained extremely low, partially because many nurses were untrained and unqualified. When multiple adolescent girls became nurses, it created a life-threatening situation for many sick and wounded soldiers left in their care. Medical supplies had also become depleted, although some were flown into the citadel, while a thousand cases of cholera continued to require quarantine.

The year obviously ended poorly for the Austro-Hungarian army. The three embarrassing Serbian front defeats accompanied severe Habsburg losses and battlefield setbacks on the Russian front until the Limanova-Lapanov victory. That success, however, could not offset the loss of morale after the Balkan front defeats, and Eastern front Habsburg troops found themselves forced on the defensive by December 20. General Conrad realized that he required another major eastern front victory to sway the wavering neutrals, Bulgaria, Romania, and particularly Italy, to retain that status. With the increasing threat of a tsarist invasion of Hungary, the Habsburg army had to block the remaining Carpathian Mountain crossings although suffering numerous recent battlefield setbacks. However, the armies first had to be rehabilitated and resupplied before any major activity could be initiated.

Thus, General Conrad faced several enormous problems at the end of 1914. The hemorrhaging troop losses had to be quickly replaced because of the unrelenting Russian numerical superiority. The crushing Habsburg military defeats at the end of December opened the invasion routes though the Carpathian Mountains, particularly between the Third and Fourth Armies’ inner flanks. Nevertheless, the Austro-Hungarian front ultimately stabilized; its defensive lines followed the course of the Dunajec River, then curved south and east along the Carpathian Mountain crests.

The Russian objective became to push Third Army forces entirely out of the Carpathian Mountains by securing the main ridges, which would eliminate the Habsburg military threat there. In addition, besieged Fortress Przemyśl could then be starved into submission without serious threat of military interference. Moreover, occupation of the main western Carpathian Mountain ridges provided a favorable starting point for a 1915 Russian campaign to invade Hungary.

The German Foreign Office and High Command meanwhile urged General Conrad to cooperate in an offensive effort to conquer the Negotine (northeastern) sector of Serbia to restore Habsburg military honor and prestige while opening a secure transportation route for sorely needed ammunition to the Turkish ally to keep it in the war. The operation might also compel Bulgaria to join the Central Powers. However, General Falkenhayn claimed that no further German troops could be removed from the hotly contested western front for transfer to the eastern one, and General Conrad certainly could not spare troops for such a campaign, because of the terrible situation on the Russian front. Only a skeleton Dual Monarchy force remained by the end of the month. The enormous losses were partially replaced, but with inadequately trained reserve troops and officers.

For Fortress Przemyśl, under siege in late September into early October and again in early November, rapidly dwindling food supplies could force capitulation soon. The late December Habsburg setbacks did not bode well for the Dual Monarchy’s overall military position. To counter the potential tsarist military threat, General Conrad proposed to launch the previously mentioned major offensive in the Carpathian Mountains, its objectives being to defeat the Russian army, protect Hungary, liberate besieged Fortress Przemyśl, and keep the neutral countries out of the war. The fatal flaw in his strategy was that the Carpathian Mountain region was unsuitable for the major military campaign he envisioned for early 1915. The rugged terrain and severe weather conditions had already presented insurmountable obstacles to his armies during late 1914. The sparse and insufficient Galician networks of roads, trails, and railroad lines severely restricted the maneuverability of large army formations. Inclement weather conditions and steep mountain terrain made the regular movement of supplies almost impossible to achieve. Under the circumstances, such a campaign would severely jeopardize the troops’ well-being and place inhuman demands on them. Furthermore, Habsburg troops had to launch deadly frontal attacks against well-prepared tsarist defensive positions. Moreover, they were compelled to do so under specific time constraints—the fate of Fortress Przemyśl demanded it!

By the end of December, only forty-five thousand infantry troops remained of the original nine hundred thousand that had been deployed during August 1914. The Habsburg army on the Russian front now consisted of only 303,000 combat soldiers in December. Meanwhile, 690,000 March Brigade, or Ersatz replacement, troops had been deployed to the Russian front, but they possessed no machine guns or artillery and lacked adequate mountain warfare equipment and training. In addition to the serious lack of artillery shells, by the end of December infantry losses stood at 85 percent of the troops originally mobilized in 1914.

A further major problem resulted from the continued failure to properly coordinate fortress and field army military efforts, which produced huge casualties for both forces. It remained significant that the Russians never had to withdraw substantial troop numbers from their siege front lines to contain the garrison breakout efforts, this despite the fact that after November 1914 tsarist third-line units served as the siege troops.

Further, serious Honvéd tactical errors have been mentioned, as well as the fact that fortress sorties were launched from the same location, with the same tactical units, and toward the same objectives. Even worse, the sortie missions proved far too ambitious considering the limited number of fortress troops deployed for the operations. Compounding the problem further, the overemphasis on flank security during the various operations proved very disadvantageous, not only because this reduced offensive troop numbers that could have better served with the main attack effort but also because the practice resulted in increased casualties. With the aid of Ruthenian spies, the Russians anticipated all of the fortress military operations and had broken the Habsburg code.

Following the disastrous December events for the Austro-Hungarian army, both opponents faced winter battle on the Carpathian Mountain front and the necessity of winning a decisive battle either to keep the neutral European countries out of the war or gain them as allies. Unfortunately, the only geographical area that General Conrad considered advantageous to launch an offensive that could provide a major victory was the Carpathian Mountains. The next chapter focuses on the Habsburg preparations for the first Carpathian Mountain Winter War in January 1915 and assesses the condition of the participating troops. Was the Habsburg army prepared to launch a major offensive in late January 1915? Were Conrad’s offensive plans realistic? Could the field armies liberate Fortress Przemyśl before it had to surrender?

Plate 1. Demolition of a fort at Fortress Przemyśl, March 22, 1915. From Przemyśl Album, M. G. Rosenfeld Papierhandlung, [ca. 1915]. Courtesy of the Library of the University of Silesia in Katowice.

Plate 2. Destroyed fort. From Przemyśl Album, M. G. Rosenfeld Papierhandlung, [ca. 1915]. Courtesy of the Library of the University of Silesia in Katowice.

Plate 3. Demolished railroad bridge on the San River. From Przemyśl Album, M. G. Rosenfeld Papierhandlung, [ca. 1915]. Courtesy of the Library of the University of Silesia in Katowice.

Plate 4. Destroyed armored train. From Przemyśl Album, M. G. Rosenfeld Papierhandlung, [ca. 1915]. Courtesy of the Library of the University of Silesia in Katowice.

Plate 5. View of Przemyśl. From Przemyśl Album, M. G. Rosenfeld Papierhandlung, [ca. 1915]. Courtesy of the Library of the University of Silesia in Katowice.

Plate 6. Inspection of the Cossacks near Fortress Przemyśl. From Przemyśl Album, M. G. Rosenfeld Papierhandlung, [ca. 1915]. Courtesy of the Library of the University of Silesia in Katowice.

Plate 7. Rebuilding train tracks near Fortress Przemyśl. From Przemyśl Album, M. G. Rosenfeld Papierhandlung, [ca. 1915]. Courtesy of the Library of the University of Silesia in Katowice.