2

AN EXPEDITION IS BORN

Among Specialists — The Turning Point —

At the Sailors’ Home —

Last Resource — Explorers Club —

The New Equipment — I Find a Companion —

A Triumvirate —

One Painter and Two Saboteurs —

To Washington —

Conference at the War Department —

To Q.M.G. with Desiderata-

Money Problems —

With Diplomats at UN —

We Fly to Ecuador

An Expedition Is Born

SO IT HAD BEGUN, BY A FIRE ON A SOUTH SEA ISLAND, where an old native sat telling legends and stories of his tribe. Many years later I sat with another old man, this time in a dark office on one of the upper floors of a big museum in New York.

Round us, in well-arranged glass cases, lay pottery fragments from the past, traces leading into the mists of antiquity. The walls were lined with books. Some of them one man had written and hardly ten men had read. The old man, who had read all these books and written some of them, sat behind his worktable, white-haired and good-humored. But now, for sure, I had trodden on his toes, for he gripped the arms of his chair uneasily and looked as if I had interrupted him in a game of solitaire.

“No!” he said. “Never!”

I imagine that Santa Claus would have looked as he did then if someone had dared to affirm that next year Christmas would be on Midsummer Day.

“You’re wrong, absolutely wrong,” he said and shook his head indignantly to drive out the idea.

“But you haven’t read my arguments yet,” I urged, nodding hopefully toward the manuscript which lay on the table.

“Arguments!” he repeated. “You can’t treat ethnographic problems as a sort of detective mystery!”

“Why not?” I said. “I’ve based all the conclusions on my own observations and the facts that science has recorded.”

“The task of science is investigation pure and simple,” he said quietly. “Not to try to prove this or that.”

He pushed the unopened manuscript carefully to one side and leaned over the table.

“It’s quite true that South America was the home of some of the most curious civilizations of antiquity, and that we know neither who they were nor where they vanished when the Incas came into power. But one thing we do know for certain—that none of the peoples of South America got over to the islands in the Pacific.”

He looked at me searchingly and continued:

“Do you know why? The answer’s simple enough. They couldn’t get there. They had no boats!”

“They had rafts,” I objected hesitatingly. “You know, balsa-wood rafts.”

The old man smiled and said calmly:

“Well, you can try a trip from Peru to the Pacific islands on a balsa-wood raft.”

I could find nothing to say. It was getting late. We both rose. The old scientist patted me kindly on the shoulder, as he saw me out, and said that if I wanted help I had only to come to him. But I must in future specialize on Polynesia or America and not mix up two separate anthropological areas. He reached back over the table.

“You’ve forgotten this,” he said and handed back my manuscript. I glanced at the title, “Polynesia and America; A Study of Prehistoric Relations.” I stuck the manuscript under my arm and clattered down the stairs out into the crowds in the street.

That evening I went down and knocked on the door of an old flat in an out-of-the-way corner of Greenwich Village. I liked bringing my little problems down here when I felt they had made life a bit tangled.

A sparse little man with a long nose opened the door a crack before he threw it wide open with a broad smile and pulled me in. He took me straight into the little kitchen, where he set me to work carrying plates and forks while he himself doubled the quantity of the indefinable but savory-smelling concoction he was heating over the gas.

“Nice of you to come,” he said. “How goes it?”

“Rottenly,” I replied. “No one will read the manuscript.”

He filled the plates and we attacked the contents.

“It’s like this,” he said. “All the people you’ve been to see think it’s just a passing idea you’ve got. You know, here in America, people turn up with so many queer ideas.”

“And there’s another thing,” I went on.

“Yes,” said he. “Your way of approaching the problem. They’re specialists, the whole lot of them, and they don’t believe in a method of work which cuts into every field of science from botany to archaeology. They limit their own scope in order to be able to dig in the depths with more concentration for details. Modern research demands that every special branch shall dig in its own hole. It’s not usual for anyone to sort out what comes up out of the holes and try to put it all together.”

He rose and reached for a heavy manuscript.

“Look here,” he said. “My last work on bird designs in Chinese peasant embroidery. Took me seven years, but it was accepted for publication at once. They want specialized research nowadays.”

Carl was right. But to solve the problems of the Pacific without throwing light on them from all sides was, it seemed to me, like doing a puzzle and only using the pieces of one color.

We cleared the table, and I helped him wash and dry the dishes.

“Nothing new from the university in Chicago?”

“No.”

“But what did your old friend at the museum say today?”

“He wasn’t interested, either,” I muttered. “He said that, as long as the Indians had only open rafts, it was futile to consider the possibility of their having discovered the Pacific islands.”

The little man suddenly began to dry his plate furiously.

“Yes,” he said at last. “To tell the truth, to me too that seems a practical objection to your theory.”

I looked gloomily at the little ethnologist whom I had thought to be a sworn ally.

“But don’t misunderstand me,” he hastened to say. “In one way I think you’re right, but in another way it’s so incomprehensible. My work on designs supports your theory.”

“Carl,” I said. “I’m so sure the Indians crossed the Pacific on their rafts that I’m willing to build a raft of the same kind myself and cross the sea just to prove that it’s possible.” “You’re mad!”

My friend took it for a joke and laughed, half-scared at the thought.

“You’re mad! A raft?”

He did not know what to say and only stared at me with a queer expression, as though waiting for a smile to show that I was joking.

He did not get one. I saw now that in practice no one would accept my theory because of the apparently endless stretch of sea between Peru and Polynesia, which I was trying to bridge with no other aid than a prehistoric raft.

Carl looked at me uncertainly. “Now we’ll go out and have a drink,” he said. We went out and had four.

My rent became due that week. At the same time a letter from the Bank of Norway informed me that I could have no more dollars. Currency restrictions. I picked up my trunk and took the subway out to Brooklyn. Here I was taken in at the Norwegian Sailors’ Home, where the food was good and sustaining and the prices suited my wallet. I got a little room a floor or two up but had my meals with all the seamen in a big dining room downstairs.

Seamen came and seamen went. They varied in type, dimensions, and degrees of sobriety but they all had one thing in common—when they talked about the sea, they knew what they were talking about. I learned that waves and rough sea did not increase with the depth of the sea or distance from land. On the contrary, squalls were often more treacherous along the coast than in the open sea. Shoal water, backwash along the coast, or ocean currents penned in close to the land could throw up a rougher sea than was usual far out. A vessel which could hold her own along an open coast could hold her own farther out. I also learned that, in a high sea, big ships were inclined to plunge bow or stern into the waves, so that tons of water would rush on board and twist steel tubes like wire, while a small boat, in the same sea, often made good weather because she could find room between the lines of waves and dance freely over them like a gull. I talked to sailors who had got safely away in boats after the seas had made their ship founder.

But the men knew little about rafts. A raft—that wasn’t a ship; it had no keel or bulwarks. It was just something floating on which to save oneself in an emergency, until one was picked up by a boat of some kind. One of the men, nevertheless, had great respect for rafts in the open sea; he had drifted about on one for three weeks when a German torpedo sank his ship in mid-Atlantic.

“But you can’t navigate a raft,” he added. “It goes sideways and backward and round as the wind takes it.”

In the library I dug out records left by the first Europeans who had reached the Pacific coast of South America. There was no lack of sketches or descriptions of the Indians’ big balsa wood rafts. They had a square sail and centerboard and a long steering oar astern. So they could be maneuvered.

Weeks passed at the Sailors’ Home. No reply from Chicago or the other cities to which I had sent copies of my theory. No one had read it.

Then, one Saturday, I pulled myself together and marched into a ship chandler’s shop down in Water Street. There I was politely addressed as “Captain” when I bought a pilot chart of the Pacific. With the chart rolled up under my arm I took the suburban train out to Ossining, where I was a regular week-end guest of a young Norwegian married couple who had a charming place in the country. My host had been a sea captain and was now office manager for the Fred Olsen Line in New York.

After a refreshing plunge in the swimming pool city life was completely forgotten for the rest of the week end, and when Ambjörg brought the cocktail tray, we sat down on the lawn in the hot sun. I could contain myself no longer but spread the chart out on the grass and asked Wilhelm if he thought a raft could carry men alive from Peru to the South Sea islands.

He looked at me rather than at the chart, half taken aback, but replied at once in the affirmative. I felt as much lightened as if I had released a balloon inside my shirt, for I knew that to Wilhelm everything that had to do with navigation and sailing was both job and hobby. He was initiated into my plans at once. To my astonishment he then declared that the idea was sheer madness.

“But you said just now that you thought it was possible,” I interrupted.

“Quite right,” he admitted. “But the chances of its going wrong are just as great. You yourself have never been on a balsa raft, and all of a sudden you’re imagining yourself across the Pacific on one. Perhaps it’ll come off, perhaps it won’t. The old Indians in Peru had generations of experience to build upon. Perhaps ten rafts went to the bottom for every one that got across—or perhaps hundreds in the course of centuries. As you say, the Incas navigated in the open sea with whole flotillas of these balsa rafts. Then, if anything went wrong, they could be picked up by the nearest raft. But who’s going to pick you up, out in mid-ocean? Even if you take a radio for use in an emergency, don’t think it’s going to be easy for a little raft to be located down among the waves thousands of miles from land. In a storm you can be washed off the raft and drowned many times over before anyone gets to you. You’d better wait quietly here till someone has had time to read your manuscript. Write again and stir them up; it’s no good if you don’t.”

“I can’t wait any longer now; I shan’t have a cent left soon.”

“Then you can come and stay with us. For that matter, how can you think of starting an expedition from South America without money?”

“It’s easier to interest people in an expedition than in an unread manuscript.”

“But what can you gain by it?”

“Destroy one of the weightiest arguments against the theory, quite apart from the fact that science will pay some attention to the affair.”

“But if things go wrong?”

“Then I shan’t have proved anything.”

“Then you’d ruin your own theory in the eyes of everyone, wouldn’t you?”

“Perhaps, but all the same one in ten might have got through before us, as you said.”

The children came out to play croquet, and we did not discuss the matter any more that day.

The next week end I was back at Ossining with the chart under my arm. And, when I left, there was a long pencil line from the coast of Peru to the Tuamotu islands in the Pacific. My friend, the captain, had given up hope of making me drop the idea, and we had sat together for hours working out the raft’s probable speed.

“Ninety-seven days,” said Wilhelm, “but remember that’s only in theoretically ideal conditions, with a fair wind all the time and assuming that the raft can really sail as you think it can. You must definitely allow at least four months for the trip and be prepared for a good deal more.”

“All right,” I said optimistically, “let us allow at least four months, but do it in ninety-seven days.”

The little room at the Sailors’ Home seemed twice as cozy as usual when I came home that evening and sat down on the edge of the bed with the chart. I paced out the floor as exactly as the bed and chest of drawers gave me room to do. Oh, yes, the raft would be much larger than this. I leaned out of the window to get a glimpse of the great city’s remote starry sky, only visible right overhead between the high yard walls. If there was little room on board the raft, anyhow there would be room for the sky and all its stars above us.

On West Seventy-Second Street, near Central Park, is one of the most exclusive clubs in New York. There is nothing more than a brightly polished little brass plate with “Explorers Club” on it to tell passers-by that there is anything out of the ordinary inside the doors. But, once inside, one might have made a parachute jump into a strange world, thousands of miles from New York’s lines of motorcars flanked by skyscrapers. When the door to New York is shut behind one, one is swallowed up in an atmosphere of lion-hunting, mountaineering, and polar life. Trophies of hippopotamus and deer, big-game rifles, tusks, war drums and spears, Indian carpets, idols and model ships, flags, photographs and maps, surround the members of the club when they assemble for a dinner or to hear lecturers from distant countries.

After my journey to the Marquesas Islands I had been elected an active member of the club, and as junior member I had seldom missed a meeting when I was in town. So, when I now entered the club on a rainy November evening, I was not a little surprised to find the place in an unusual state. In the middle of the floor lay an inflated rubber raft with boat rations and accessories, while parachutes, rubber overalls, safety jackets, and polar equipment covered walls and tables, together with balloons for water distillation, and other curious inventions. A newly elected member of the club, Colonel Haskin, of the equipment laboratory of the Air Material Command, was to give a lecture and demonstrate a number of new military inventions which, he thought, would in the future be of use to scientific expeditions in both north and south.

After the lecture there was a vigorous discussion. The well-known Danish polar explorer Peter Freuchen, tall and bulky, rose with a skeptical shake of his huge beard. He had no faith in such new-fangled patents. He himself had once used a rubber boat and bag tent on one of his Greenland expeditions instead of an Eskimo kayak and igloo, and it had all but cost him his life. First he had nearly been frozen to death in a snowstorm because the zipper fastening of the tent had frozen up so that he could not even get in. And after that he had been out fishing when the hook caught in the inflated rubber boat, and the boat was punctured and sank under him like a bit of rag. He and an Eskimo friend had managed to get ashore that time in a kayak which came to their help. He was sure no clever modern inventor could sit in his laboratory and think out anything better than what the experience of thousands of years had taught the Eskimos to use in their own regions.

The discussion ended with a surprising offer from Colonel Haskin. Active members of the club could, on their next expeditions, select any they liked of the new inventions he had demonstrated, on the sole condition that they should let his laboratory know what they thought of the things when they came back.

That was that. I was the last to leave the clubrooms that evening. I had to go over every minute detail of all this brand-new equipment which had so suddenly tumbled into my hands and which was at my disposal for the asking. It was exactly what I wanted—equipment with which we could try to save our lives if, contrary to expectation, our wooden raft should show signs of breaking up and we had no other rafts near by.

All this equipment was still occupying my thoughts at the breakfast table in the Sailors’ Home next morning when a well-dressed young man of athletic build came along with his breakfast tray and sat down at the same table as myself. We began to chat, and it appeared that he too was not a seaman but a university-trained engineer from Trondheim, who was in America to buy machinery parts and obtain experience in refrigerating technique. He was living not far away and often had meals at the Sailors’ Home because of the good Norwegian cooking there.

He asked me what I was doing, and I then gave him a short account of my plans. I said that, if I did not get a definite answer about my manuscript before the end of the week, I should get under way with the starting of the raft expedition. My table companion did not say much but listened with great interest.

Four days later we ran across each other again in the same dining room.

“Have you decided whether you’re going on your trip or not?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said. “I’m going.”

“When?”

“As soon as possible. If I hang about much longer now, the gales will be coming up from the Antarctic and it will be hurricane season in the islands, too. I must leave Peru in a very few months, but I must get money first and get the whole business organized.”

“How many men will there be?”

“I’ve thought of having six men in all; that’ll give some change of society on board the raft and is the right number for four hours’ steering in every twenty-four hours.”

He stood for a moment or two, as though chewing over a thought, then burst out emphatically:

“The devil, but how I’d like to be in it! I could undertake technical measurements and tests. Of course, you’ll have to support your experiment with accurate measurements of winds and currents and waves. Remember that you’re going to cross vast spaces of sea which are practically unknown because they lie outside all shipping routes. An expedition like yours can make interesting hydrographic and meteorological investigations; I could make good use of my thermodynamics.”

I knew nothing about the man beyond what an open face can say. It may say a good deal.

“All right,” I said. “We’ll go together.”

His name was Herman Watzinger; he was as much of a landlubber as myself.

A few days later I took Herman as my guest to the Explorers Club. Here we ran straight into the polar explorer Peter Freuchen. Freuchen has the blessed quality of never disappearing in a crowd. As big as a barn door and bristling with beard, he looks like a messenger from the open tundra. A special atmosphere surrounds him—it is as though he were going about with a grizzly bear on a lead.

We took him over to a big map on the wall and told him about our plan of crossing the Pacific on an Indian raft. His boyish blue eyes grew as large as saucers as he listened. Then he stamped his wooden leg on the floor and tightened his belt several holes.

“Damn it, boys! I should like to go with you!”

The old Greenland traveler filled our beer mugs and began to tell us of his confidence in primitive peoples’ watercraft and these peoples’ ability to make their way by accommodating themselves to nature both on land and at sea. He himself had traveled by raft down the great rivers of Siberia and towed natives on rafts astern of his ship along the coast of the Arctic. As he talked, he tugged at his beard and said we were certainly going to have a great time.

Through Freuchen’s eager support of our plan the wheels began to turn at a dangerous speed, and they soon ran right into the printers’ ink of the Scandinavian Press. The very next morning there came a violent knocking on my door in the Sailors’ Home; I was wanted on the telephone in the passage downstairs. The result of the conversation was that Herman and I, the same evening, rang the doorbell of an apartment in a fashionable quarter of the city. We were received by a well-dressed young man in patent-leather slippers, wearing a silk dressing gown over a blue suit. He made an impression almost of softness and apologized for having a cold with a scented handkerchief held under his nose. Nonetheless we knew that this fellow had made a name in America by his exploits as an airman in the war. Besides our apparently delicate host two energetic young journalists, simply bursting with activity and ideas, were present. We knew one of them as an able correspondent.

Our host explained over a bottle of good whisky that he was interested in our expedition. He offered to raise the necessary capital if we would undertake to write newspaper articles and go on lecture tours after our return. We came to an agreement at last and drank to successful co-operation between the backers of the expedition and those taking part in it. From now on all our economic problems would be solved; they were taken over by our backers and would not trouble us. Herman and I were at once to set about raising a crew and equipment, build a raft, and get off before the hurricane season began.

Next day Herman resigned his post, and we set about our task seriously. I had already obtained a promise from the research laboratory of the Air Material Command to send everything I asked for and more through the Explorers Club; they said that an expedition such as ours was ideal for testing their equipment. This was a good start. Our most important tasks were now, first of all, to find four suitable men who were willing to go with us on the raft and to obtain supplies for the journey.

A party of men who were to put out to sea together on board a raft must be chosen with care. Otherwise there would be trouble and mutiny after a month’s isolation at sea. I did not want to man the raft with sailors; they knew hardly any more about managing a raft than we did ourselves, and I did not want to have it argued afterward, when we had completed the voyage, that we made it because we were better seamen than the old raft-builders in Peru. Nevertheless, we wanted one man on board who at any rate could use a sextant and mark our course on a chart as a basis for all our scientific reports.

“I know a good fellow, a painter,” I said to Herman. “He’s a big hefty chap who can play the guitar and is full of fun. He went through navigation school and sailed round the world several times before he settled down at home with brush and palette. I’ve known him since we were boys and have often been on camping tours with him in the mountains at home. I’ll write and ask him; I’m sure he’ll come.”

“He sounds all right,” Herman nodded, “and then we want someone who can manage the radio.”

“Radio!” I said, horrified. “What the hell do we want with that? It’s out of place on a prehistoric raft.”

“Not at all—it’s a safety precaution which won’t have any effect on your theory so long as we don’t send out any SOS for help. And we shall need the radio to send out weather observations and other reports. But it’ll be no use for us to receive gale warnings because there are no reports for that part of the ocean, and, even if there were, what good would they be to us on a raft?”

His arguments gradually swamped all my protests, the main ground for which was a lack of affection for push buttons and turning knobs.

“Curiously enough,” I admitted, “I happen to have the best connections for getting into touch by radio over great distances with tiny sets. I was put into a radio section in the war. Every man in the right place, you know. But I shall certainly write a line to Knut Haugland and Torstein Raaby.”

“Do you know them?”

“Yes. I met Knut for the first time in England in 1944. He’d been decorated by the British for having taken part in the parachute action that held up the German efforts to get the atomic bomb; he was the radio operator, you know, in the heavy water sabotage at Rjukan. When I met him, he had just come back from another job in Norway; the Gestapo had caught him with a secret radio set inside a chimney in the Maternity Clinic in Oslo. The Nazis had located him by D/F, and the whole building was surrounded by German soldiers with machine-gun posts in front of every single door. Fehmer, the head of the Gestapo, was standing in the courtyard himself waiting for Knut to be carried down. But it was his own men who were carried down. Knut fought his way with his pistol from the attic down to the cellar, and from there out into the back yard, where he disappeared over the hospital wall with a hail of bullets after him. I met him at a secret station in an old English castle; he had come back to organize underground liaison among more than a hundred transmitting stations in occupied Norway.

“I myself had just finished my training as a parachutist, and our plan was to jump together in the Nordmark near Oslo. But just then the Russians marched into the Kirkenes region, and a small Norwegian detachment was sent from Scotland to Finnmark to take over the operations, so to speak, from the whole Russian army. I was sent up there instead. And there I met Torstein.

“It was real Arctic winter up in those parts, and the northern lights flashed in the starry sky which was arched over us, pitch black, all day and all night. When we came to the ash heaps of the burned area in Finnmark, frozen blue and wearing furs, a cheery fellow with blue eyes and bristly fair hair crept out of a little hut up in the mountains. This was Torstein Raaby. He had first escaped to England, where he went through special training, and then he’d been smuggled into Norway somewhere near Tromsö. He’d been in hiding with a little transmitting set close to the battleship ‘Tirpitz’ and for ten months he had sent daily reports to England about all that happened on board. He sent his reports at night by connecting his secret transmitter to a receiving aerial put up by a German officer. It was his regular reports that guided the British bombers who at last finished off the ‘Tirpitz.’

“Torstein escaped to Sweden and from there over to England again, and then he made a parachute jump with a new radio set behind the German lines up in the wilds of Finnmark. When the Germans retreated, he found himself sitting behind our own lines and came out of his hiding place to help us with his little radio, as our main station had been destroyed by a mine. I’m ready to bet that both Knut and Torstein are fed up with hanging about at home now and would be glad to go for a little trip on a wooden raft.”

“Write and ask them,” Herman proposed.

So I wrote a short letter, without any disingenuous persuasions, to Erik, Knut, and Torstein:

“Am going to cross Pacific on a wooden raft to support a theory that the South Sea islands were peopled from Peru. Will you come? I guarantee nothing but a free trip to Peru and the South Sea islands and back, but you will find good use for your technical abilities on the voyage. Reply at once.”

Next day the following telegram arrived from Torstein:

“COMING. TORSTEIN.”

The other two also accepted.

As sixth member of the party we had in view now one man and now another, but each time some obstacle arose. In the meantime Herman and I had to attack the supply problem. We did not mean to eat llama flesh or dried kumara potatoes on our trip, for we were not making it to prove that we had once been Indians ourselves. Our intention was to test the performance and quality of the Inca raft, its seaworthiness and loading capacity, and to ascertain whether the elements would really propel it across the sea to Polynesia with its crew still on board. Our native forerunners could certainly have managed to live on dried meat and fish and kumara potatoes on board, as that was their staple diet ashore. We were also going to try to find out, on the actual trip, whether they could have obtained additional supplies of fresh fish and rain water while crossing the sea. As our own diet I had thought of simple field service rations, as we knew them from the war.

Just at that time a new assistant to the Norwegian military attaché in Washington had arrived. I had acted as second in command of his company in Finnmark and knew that he was a “ball of fire,” who loved to attack and solve with savage energy any problem set before him. Björn Rörholt was a man of that vital type which feels quite lost if it has fought its way out into the open without immediately sighting a new problem to tackle.

I wrote to him explaining the situation and asked him to use his tracking sense to smell out a contact man in the supply department of the American army. The chances were that the laboratory was experimenting with new field rations we could test, in the same way as we were testing equipment for the Air Force laboratory.

Two days later Björn telephoned us from Washington. He had been in contact with the foreign liaison section of the American War Department, and they would like to know what it was all about.

Herman and I took the first train to Washington.

We found Björn in his room in the military attaché’s office.

“I think it’ll be all right,” he said. “We’ll be received at the foreign liaison section tomorrow provided we bring a proper letter from the colonel.”

The “colonel” was Otto Munthe-Kaas, the Norwegian military attaché. He was well-disposed and more than willing to give us a proper letter of introduction when he heard what our business was.

When we came to fetch the document next morning, he suddenly rose and said he thought it would be best if he came with us himself. We drove out in the colonel’s car to the Pentagon building to the offices of the War Department. The colonel and Björn sat in front in their smartest military turnout, while Herman and I sat behind and peered through the windshield at the huge Pentagon building, which towered up on the plain before us. This gigantic building with thirty thousand clerks and sixteen miles of corridors was to form the frame of our impending raft conference with military “high-ups.” Never, before or after, did the little raft seem to Herman and me so helplessly small.

After endless wanderings in ramps and corridors we reached the door of the foreign liaison section, and soon, surrounded by brand-new uniforms, we were sitting round a large mahogany table at which the head of the foreign liaison section himself presided.

The stern, broad-built West Point officer, who bulked big at the end of the table, had a certain difficulty at first in understanding what the connection between the American War Department and our wooden raft was, but the colonel’s well-considered words, and the favorable result of a hurricane-like examination by the officers round the table, slowly brought him over to our side, and he read with interest the letter from the equipment laboratory of the Air Material Command. Then he rose and gave his staff a concise order to help us through the proper channels and, wishing us good luck for the present, marched out of the conference room. When the door had shut on him, a young staff captain whispered in my ear:

“I’ll bet you’ll get what you want. It sounds like a minor military operation and brings a little change into our daily office peacetime routine; besides, it’ll be a good opportunity of methodically testing equipment.”

The liaison office at once arranged a meeting with Colonel Lewis at the quartermaster general’s experimental laboratory, and Herman and I were taken over there by car.

Colonel Lewis was an affable giant of an officer with a sportsman’s bearing. He at once called in the men in charge of experiments in the different sections. All were amicably disposed and immediately suggested quantities of equipment they would like us to test thoroughly. They exceeded our wildest hopes as they rattled off the names of nearly everything we could want, from field rations to sunburn ointment and splash-proof sleeping bags. Then they took us on an extensive tour to look at the things. We tasted special rations in smart packings; we tested matches which struck well even if they had been dipped in water, new primus stoves and water kegs, rubber bags and special boots, kitchen utensils and knives which would float, and all that an expedition could want.

I glanced at Herman. He looked like a good, expectant little boy walking through a chocolate shop with a rich aunt. The colonel walked in front demonstrating all these delights, and when the tour was completed staff clerks had made note of the kinds of goods and the quantities we required. I thought the battle was won and felt only an urge to rush home to the hotel in order to assume a horizontal position and think things over in peace and quiet. Then the tall, friendly colonel suddenly said:

“Well, now we must go in and have a talk with the boss; it’s he who’ll decide whether we can give you these things.”

I felt my heart sink down into my boots. So we were to start our eloquence right from the beginning again, and heaven alone knew what kind of man the “boss” was!

We found that the boss was a little officer with an intensely earnest manner. He sat behind his writing table and examined us with keen blue eyes as we came into the office. He asked us to sit down.

Plans being discussed before the start in the Explorers Club in New York. From left to right: Chief of Clannfhearghuis, Herman Watzinger, the author, Greenland explorer Peter Freuchen.

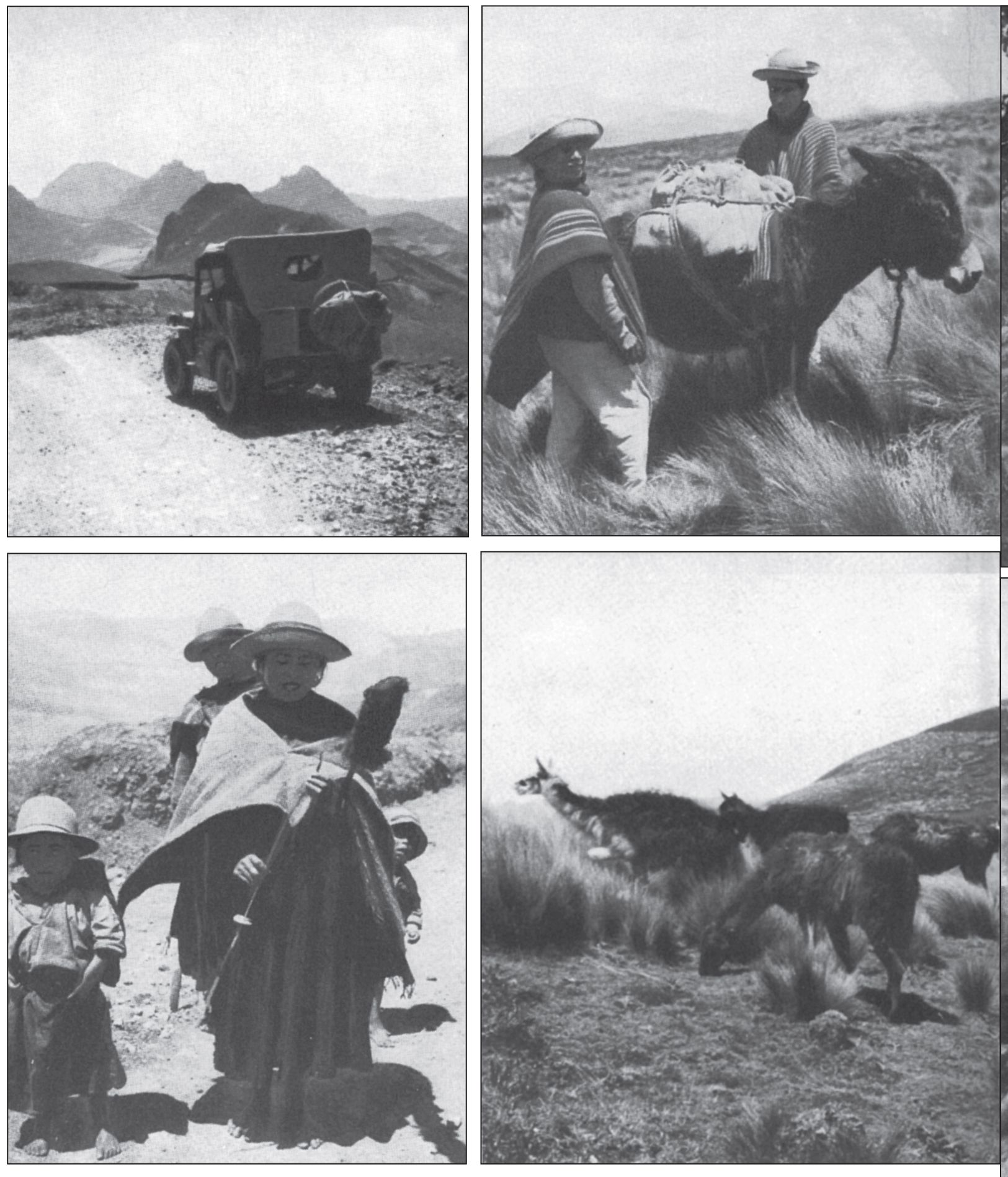

Over the Andes for wood—our jeep on a mountain road 13,000 feet above sea level. Indians with pack donkeys, Indian women spinning wool as they walk, and flocks of llamas were the only living creatures we met.

In the Ecuadorian jungle we found our balsa logs. We felled the biggest trees we could find, peeled off the bark in Indian style, and built a makeshift raft on which we drifted down the Palenque and the Guayas to the Pacific.

The six members of the Kon-Tiki expedition. From left to right: Knut Haugland, Bengt Danielsson, the author, Erik Hesselberg, Torstein Raaby, Herman Watzinger.

Building the raft in Peru. We lashed the nine big balsa logs together with ordinary hemp ropes, using neither nails nor metal in any form.

“Well, what do these gentlemen want?” he asked Colonel Lewis sharply, without taking his eyes off mine.

“Oh, a few little things,” Lewis hastened to reply. He explained the whole of our errand in outline, while the chief listened patiently without moving a finger.

“And what can they give us in return?” he asked, quite unimpressed.

“Well,” said Lewis in a conciliatory tone, “we hoped that perhaps the expedition would be able to write reports on the new provisions and some of the equipment, based on the severe conditions in which they will be using it.”

The intensely earnest officer behind the writing table leaned back in his chair with unaffected slowness, with his eyes still fixed on mine, and I felt myself sinking to the bottom of the deep leather chair as he said coolly:

“I don’t see at all how they can give us anything in return.”

There was dead silence in the room. Colonel Lewis fingered his collar, and neither of us said a word.

“But,” the chief suddenly broke out, and now a gleam had come into the corner of his eye, “courage and enterprise count, too. Colonel Lewis, let them have the things!”

I was still sitting, half intoxicated with delight, in the cab which was taking us home to the hotel, when Herman began to laugh and giggle to himself at my side.

“Are you tight?” I asked anxiously.

“No,” he laughed shamelessly, “but I’ve been calculating that the provisions we got include 684 boxes of pineapple, and that’s my favorite dish.”

There are a thousand things to be done, and mostly at the same time, when six men and a wooden raft and its cargo are to assemble at a place down on the coast of Peru. And we had three months and no Aladdin’s lamp at our disposal.

We flew to New York with an introduction from the liaison office and met Professor Behre at Columbia University. He was head of the War Department’s Geographical Research Committee, and it was he who pressed the buttons which at last brought Herman all his valuable instruments and apparatus for scientific measurements.

Then we flew to Washington to meet Admiral Glover at the Naval Hydrographic Institute. The good-natured old sea dog called in all his officers and pointed to the chart of the Pacific on the wall as he introduced Herman and me.

“These young gentlemen want to check up on our current maps. Help them!”

When the wheels had rolled a bit further, the English Colonel Lumsden called a conference at the British Military Mission in Washington to discuss our future problems and the chances of a favorable outcome. We received plenty of good advice and a selection of British equipment which was flown over from England to be tried out on the raft expedition. The British medical officer was an enthusiastic advocate of a mysterious shark powder. We were to sprinkle a few pinches of the powder on the water if a shark became too impudent, and the shark would vanish immediately.

“Sir,” I said politely, “can we rely on this powder?”

“Well,” said the Englishman, smiling, “that’s just what we want to find out ourselves!”

When time is short and plane replaces train, while taxi replaces legs, one’s wallet crumples up like a withered herbarium. When we had spent the cost of my return ticket to Norway, we went and called on our friends and backers in New York to get our finances straight. There we encountered surprising and discouraging problems. The financial manager was ill in bed with fever, and his two colleagues were powerless till he was in action again. They stood firmly by our economic agreement, but they could do nothing for the time being. We were asked to postpone the business, a useless request, for we could not stop the numerous wheels which were now revolving vigorously. We could only hold on now; it was too late to stop or brake. Our friends the backers agreed to dissolve the whole syndicate in order to give us a free hand to act quickly and independently without them.

So there we were in the street with our hands in our trousers pockets.

“December, January, February,” said Herman.

“And at a pinch March,” said I, “but then we simply must start!”

If all else seemed obscure, one thing was clear to us. Ours was a journey with an objective, and we did not want to be classed with acrobats who roll down Niagara in empty barrels or sit on the knobs of flag staffs for seventeen days.

“No chewing-gum or pop backing,” Herman said.

On this point we were in profound agreement.

We could get Norwegian currency. But that did not solve the problems on our side of the Atlantic. We could apply for a grant from some institution, but we could scarcely get one for a disputed theory; after all, that was just why we were going on the raft expedition. We soon found that neither press nor private promoters dared to put money into what they themselves and all the insurance companies regarded as a suicide voyage; but, if we came back safe and sound, it would be another matter.

Things looked pretty gloomy, and for many days we could see no ray of hope. It was then that Colonel Munthe-Kaas came into the picture again.

“You’re in a fix, boys,” he said. “Here’s a check to begin with. You can return it when you come back from the South Sea islands.”

Several other people followed his example, and my private loan was soon big enough to tide us over without help from agents or others. We could fly to South America and start building the raft.

The old Peruvian rafts were built of balsa wood, which in a dry state is lighter than cork. The balsa tree grows in Peru, but only beyond the mountains in the Andes range, so the seafarers in Inca times went up along the coast to Ecuador, where they felled their huge balsa trees right down on the edge of the Pacific. We meant to do the same.

Today’s travel problems are different from those of Inca times. We have cars and planes and travel bureaus but, so as not to make things altogether too easy, we have also impediments called frontiers, with brass-buttoned attendants who doubt one’s alibi, maltreat one’s luggage, and weigh one down with stamped forms—if one is lucky enough to get in at all. It was the fear of these men with brass buttons that decided us we could not land in South America with packing cases and trunks full of strange devices, raise our hats, and ask politely in broken Spanish to be allowed to come in and sail away on a raft. We should be clapped into jail.

“No,” said Herman. “We must have an official introduction.”

One of our friends in the dissolved triumvirate was a correspondent at the United Nations, and he offered to take us out there by car for aid. We were greatly impressed when we came into the great hall of the assembly, where men of all nations sat on benches side by side listening silently to the flow of speech from a black-haired Russian in front of the gigantic map of the world that decorated the back wall.

Our friend the correspondent managed in a quiet moment to get hold of one of the delegates from Peru and, later, one of Ecuador’s representatives. On a deep leather sofa in an antechamber they listened eagerly to our plan of crossing the sea to support a theory that men of an ancient civilization from their own country had been the first to reach the Pacific islands. Both promised to inform their governments and guaranteed us support when we came to their respective countries. Trygve Lie, passing through the anteroom, came over to us when he heard we were countrymen of his, and someone proposed that he should come with us on the raft. But there were billows enough for him on land. The assistant secretary of the United Nations, Dr. Benjamin Cohen from Chile, was himself a well-known amateur archaeologist, and he gave me a letter to the President of Peru, who was a personal friend of his. We also met in the hall the Norwegian ambassador, Wilhelm von Munthe of Morgenstierne, who from then on gave the expedition invaluable support.

So we bought two tickets and flew to South America. When the four heavy engines began to roar one after another, we sank into our seats exhausted. We had an unspeakable feeling of relief that the first stage of the program was over and that we were now going straight ahead to the adventure.