8

AMONG POLYNESIANS

A Robinson Crusoe Touch — Fear of Relief —

All Well, Kon-Tiki! — Other Wrecks —

Uninhabited Islands —

Fight with Marine Eels — Natives Find Us —

Ghosts on the Reef — Envoy to the Chief —

The Chief Visits Us —

The kon-Tiki Is Recognized — A High Tide —

Our Craft’s Overland Cruise —

Only Four on the Island — Natives Fetch Us —

Reception in the Village —

Forefathers from the Sunrise — Hula Feast —

Medicine Men on the Air —

We Become Royalty — Another Shipwreck —

The “Tamara” Salvages the “Maoae” —

To Tahiti —

Meeting on the Quay—A Royal Stay —

Six Wreaths

Among Polynesians

OUR LITTLE ISLAND WAS UNINHABITED. WE SOON GOT to know every palm clump and every beach, for the island was barely two hundred yards across. The highest point was less than six feet above the lagoon.

Over our heads, in the palm tops, there hung great clusters of green coconut husks, which insulated their contents of cold coconut milk from the tropical sun, so we should not be thirsty in the first weeks. There were also ripe coconuts, a swarm of hermit crabs, and all sorts of fish in the lagoon; we should be well off.

On the north side of the island we found the remnants of an old, unpainted wooden cross, half buried in the coral sand. Here there was the view northward along the reef to the stripped wreck, which we had first seen closer in as we drifted by on the way to our stranding. Still farther northward we saw in a bluish haze the palm tufts of another small island. The island to southward, on which the trees grew thickly, was much closer. We saw no sign of life there, either, but for the time we had other matters to think about.

Robinson Crusoe Hesselberg came limping up in his big straw hat with his arms full of crawling hermit crabs. Knut set fire to some dry wood, and soon we had crab and coconut milk with coffee for dessert.

“Feels all right being ashore, doesn’t it, boys?” Knut asked delightedly.

He had himself enjoyed this feeling once before on the voyage, at Angatau. As he spoke, he stumbled and poured half a kettle of boiling water over Bengt’s bare feet. We were all of us a bit unsteady the first day ashore, after 101 days on board the raft, and would suddenly begin reeling about among the palm trunks because we had put out a foot to counter a sea that did not come.

When Bengt handed over to us our respective mess utensils, Erik grinned broadly. I remember that, after the last meal on board, I had leaned over the side of the raft and washed up as usual, while Erik looked in across the reef, saying: “I don’t think I shall bother to wash up today.” When he found his things in the kitchen box, they were as clean as mine.

After the meal and a good stretch on the ground we set about putting together the soaked radio apparatus; we must do it quickly so that Torstein and Knut might get on the air before the man on Rarotonga sent out a report of our sad end.

Most of the radio equipment had already been brought ashore, and among the things which lay drifting on the reef Bengt found a box, on which he laid hands. He jumped high into the air from an electric shock; there was no doubt that the contents belonged to the radio section. While the operators unscrewed, coupled, and put together, we others set about pitching camp.

Out on the wreck we found the heavy waterlogged sail and dragged it ashore. We stretched it between two big palms in a little opening, looking on to the lagoon, and supported two other corners with bamboo sticks which came drifting in from the wreck. A thick hedge of wild flowering bushes forced the sail together so that we had a roof and three walls and, moreover, a clear view of the shining lagoon, while our nostrils were filled with an insinuating scent of blossoms. It was good to be here. We all laughed quietly and enjoyed our ease; we each made our beds of fresh palm leaves, pulling up loose branches of coral which stuck up inconveniently out of the sand. Before night fell we had a very pleasant rest, and over our heads we saw the big bearded face of good old Kon-Tiki. No longer did he swell out his breast with the east wind behind him. He now lay motionless on his back looking up at the stars which came twinkling out over Polynesia.

On the bushes round us hung wet flags and sleeping bags, and soaked articles lay on the sand to dry. Another day on this island of sunshine and everything would be nicely dry. Even the radio boys had to give it up until the sun had a chance of drying the inside of their apparatus next day. We took the sleeping bags down from the trees and turned in, disputing boastfully as to who had the driest bag. Bengt won, for his did not squelch when he turned over. Heavens, how good it was to be able to sleep!

When we woke next morning at sunrise, the sail was bent down and full of rain water as pure as crystal. Bengt took charge of this asset and then ambled down to the lagoon and jerked ashore some curious breakfast fish which he decoyed into channels in the sand.

That night Herman had had pains in the neck and back where he had injured himself before the start from Lima, and Erik had a return of his vanished lumbago. Otherwise we had come out of the trip over the reef astonishingly lightly, with scratches and small wounds, except for Bengt who had had a blow on the forehead when the mast fell and had a slight concussion. I myself looked most peculiar, with my arms and legs bruised blue black all over by the pressure against the rope.

But none of us was in such a bad state that the sparkling clear lagoon did not entice him to a brisk swim before breakfast. It was an immense lagoon. Far out it was blue and rippled by the trade wind, and it was so wide that we could only just see the tops of a row of misty, blue palm islands which marked the curve of the atoll on the other side. But here, in the lee of the islands, the trade wind rustled peacefully in the fringed palm tops, making them stir and sway, while the lagoon lay like a motionless mirror below and reflected all their beauty. The bitter salt water was so pure and clear that gaily colored corals in nine feet of water seemed so near the surface that we thought we should cut our toes on them in swimming. And the water abounded in beautiful varieties of colorful fish. It was a marvelous world in which to disport oneself. The water was just cold enough to be refreshing, and the air was pleasantly warm and dry from the sun. But we must get ashore again quickly today; Rarotonga would broadcast alarming news if nothing had been heard from the raft at the end of the day.

Coils and radio parts lay drying in the tropical sun on slabs of coral, and Torstein and Knut coupled and screwed. The whole day passed, and the atmosphere grew more and more hectic. The rest of us abandoned all other jobs and crowded round the radio in the hope of being able to give assistance. We must be on the air before 10 P.M. Then the thirty-six hours’ time limit would be up, and the radio amateur on Rarotonga would send out appeals for airplane and relief expeditions.

Noon came, afternoon came, and the sun set. If only the man on Rarotonga would contain himself! Seven o’clock, eight, nine. The tension was at breaking point. Not a sign of life in the transmitter, but the receiver, an NC—173, began to liven up somewhere at the bottom of the scale and we heard faint music. But not on the amateur wave length. It was eating its way up, however; perhaps it was a wet coil which was drying inward from one end. The transmitter was still stone-dead—short circuits and sparks everywhere.

There was less than an hour left. This would never do. The regular transmitter was given up, and a little sabotage transmitter from wartime was tried again. We had tested it several times before in the course of the day, but without result. Now perhaps it had become a little drier. All the batteries were completely ruined, and we got power by cranking a tiny hand generator. It was heavy, and we four who were laymen in radio matters took turns all day long sitting and turning the infernal thing.

The thirty-six hours would soon be up. I remember someone whispering “Seven minutes more,” “Five minutes more,” and then no one would look at his watch again. The transmitter was as dumb as ever, but the receiver was sputtering upward toward the right wave length. Suddenly it crackled on the Rarotonga man’s frequency, and we gathered that he was in full contact with the telegraph station in Tahiti. Soon afterward we picked up the following fragment of a message sent out from Rarotonga:

“- - - no plane this side of Samoa. I am quite sure- - -.”

Then it died away again. The tension was unbearable. What was brewing out there? Had they already begun to send out plane and rescue expeditions? Now, no doubt, messages concerning us were going over the air in every direction.

The two operators worked feverishly. The sweat trickled from their faces as freely as it did from ours who sat turning the handle. Power began slowly to come into the transmitter’s aerial, and Torstein pointed ecstatically to an arrow which swung slowly up over a scale when he held the Morse key down. Now it was coming!

We turned the handle madly while Torstein called Rarotonga. No one heard us. Once more. Now the receiver was working again, but Rarotonga did not hear us. We called Hal and Frank at Los Angeles and the Naval School at Lima, but no one heard us.

Then Torstein sent out a CQ message: that is to say, he called all the stations in the world which could hear us on our special amateur wave length.

That was of some use. Now a faint voice out in the ether began to call us slowly. We called again and said that we heard him. Then the slow voice out in the ether said:

“My name is Paul—I live in Colorado. What is your name and where do you live?”

This was a radio amateur. Torstein seized the key, while we turned the handle, and replied:

“This is the Kon-Tiki. We are stranded on a desert island in the Pacific.”

Paul did not believe the message. He thought it was a radio amateur in the next street pulling his leg, and he did not come on the air again. We tore our hair in desperation. Here were we, sitting under the palm tops on a starry night on a desert island, and no one even believed what we said.

Torstein did not give up; he was at the key again sending “All well, all well, all well” unceasingly. We must at all costs stop all this rescue machinery from starting out across the Pacific.

Then we heard, rather faintly, in the receiver:

“If all’s well, why worry?”

Then all was quiet in the ether. That was all.

We could have leaped into the air and shaken down all the coconuts for sheer desperation, and heaven knows what we should have done if both Rarotonga and good old Hal had not suddenly heard us. Hal wept for delight, he said, at hearing LI 2 B again. All the tension stopped immediately; we were once more alone and undisturbed on our South Sea island and turned in, worn out, on our beds of palm leaves.

Next day we took it easy and enjoyed life to the full. Some bathed, others fished or went out exploring on the reef in search of curious marine creatures, while the most energetic cleared up in camp and made our surroundings pleasant. Out on the point which looked toward the Kon-Tiki we dug a hole on the edge of the trees, lined it with leaves, and planted in it the sprouting coconut from Peru. A cairn of corals was erected beside it, opposite the place where the Kon-Tiki had run ashore.

The Kon-Tiki had been washed still farther in during the night and lay almost dry in a few pools of water, squeezed in among a group of big coral blocks a long way through the reef.

After a thorough baking in the warm sand Erik and Herman were in fine fettle again and were anxious to go southward along the reef in the hope of getting over to the large island which lay down there. I warned them more against eels than against sharks, and each of them stuck his long machete knife into his belt. I knew the coral reef was the habitat of a frightful eel with long poisonous teeth which could easily tear off a man’s leg. They wriggle to the attack with lightning rapidity and are the terror of the natives, who are not afraid to swim round a shark.

The two men were able to wade over long stretches of the reef to southward, but there were occasional channels of deeper water running this way and that where they had to jump in and swim. They reached the big island safely and waded ashore. The island, long and narrow and covered with palm forest, ran farther south between sunny beaches under the shelter of the reef. The two continued along the island till they came to the southern point. From here the reef, covered with white foam, ran on southward to other distant islands. They found the wreck of a big ship down there; she had four masts and lay on the shore cut in two. She was an old Spanish sailing vessel which had been loaded with rails, and rusty rails lay scattered all along the reef. They returned along the other side of the island but did not find so much as a track in the sand.

On the way back across the reef they were continually coming upon curious fish and were trying to catch some of them when they were suddenly attacked by no fewer than eight large eels. They saw them coming in the clear water and jumped up on to a large coral block, round and under which the eels writhed. The slimy brutes were as thick as a man’s calf and speckled green and black like poisonous snakes, with small heads, malignant snake eyes, and teeth an inch long and as sharp as an awl. The men hacked with their machete knives at the little swaying heads which came writhing toward them; they cut the head off one and another was injured. The blood in the sea attracted a whole flock of young blue sharks which attacked the dead and injured eels, while Erik and Herman were able to jump over to another block of coral and get away.

On the same day I was wading in toward the island when something, with a lightning movement, caught hold of my ankle on both sides and held on tight. It was a cuttlefish. It was not large, but it was a horrible feeling to have the cold gripping arms about one’s limb and to exchange looks with the evil little eyes in the bluish-red, beaked sack which constituted the body. I jerked in my foot as hard as I could, and the squid, which was barely three feet long, followed it without letting go. It must have been the bandage on my foot which attracted it. I dragged myself in jerks toward the beach with the disgusting carcass hanging on to my foot. Only when I reached the edge of the dry sand did it let go and retreat slowly through the shallow water, with arms outstretched and eyes directed shoreward, as though ready for a new attack if I wanted one. When I threw a few lumps of coral at it, it darted away.

Our various experiences out on the reef only added a spice to our heavenly existence on the island within. But we could not spend all our lives here, and we must begin to think about how we should get back to the outer world. After a week the Kon-Tiki had bumped her way in to the middle of the reef, where she lay stuck fast on dry land. The great logs had pushed away and broken off large slabs of coral in the effort to force their way forward to the lagoon, but now the wooden raft lay immovable, and all our pulling and all our pushing were equally unavailing. If we could only get the wreck into the lagoon, we could always splice the mast and rig her sufficiently to be able to sail with the wind across the friendly lagoon and see what we found on the other side. If any of the islands were inhabited, it must be some of those which lay along the horizon away in the east, where the atoll turned its façade toward the lee side.

The days passed.

Then one morning some of the fellows came tearing up and said they had seen a white sail on the lagoon. From up among the palm trunks we could see a tiny speck which was curiously white against the opal-blue lagoon. It was evidently a sail close to land on the other side. We could see that it was tacking. Soon another appeared.

They grew in size, as the morning went on, and came nearer. They came straight toward us. We hoisted the French flag on a palm tree and waved our own Norwegian flag on a pole. One of the sails was now so near that we could see that it belonged to a Polynesian outrigger canoe. The rig was of more recent type. Two brown figures stood on board gazing at us. We waved. They waved back and sailed straight in on to the shallows.

“Ia-ora-na,” we greeted them in Polynesian.

“la-ora-na,” they shouted back in chorus, and one jumped out and dragged his canoe after him as he came wading over the sandy shallows straight toward us.

The two men had white men’s clothes but brown men’s bodies. They were barelegged, well built, and wore homemade straw hats to protect them from the sun. They landed and approached us rather uncertainly, but, when we smiled and shook hands with them in turn, they beamed on us with rows of pearly teeth which said more than words.

Our Polynesian greeting had astonished and encouraged the two canoers in exactly the same way as we ourselves had been deceived when their kinsman off Angatau had called out “Good night,” and they reeled off a long rhapsody in Polynesian before they realized that their outpourings were going wide of the mark. Then they had nothing more to say but giggled amiably and pointed to the other canoe which was approaching.

There were three men in this, and, when they waded ashore and greeted us, it appeared that one of them could talk a little French. We learned that there was a native village on one of the islands across the lagoon, and from it the Polynesians had seen our fire several nights earlier. Now there was only one passage leading in through the Raroia reef to the circle of islands around the lagoon, and, as this passage ran right past the village, no one could approach these islands inside the reef without being seen by the inhabitants of the village. The old people in the village, therefore, had come to the conclusion that the light they saw on the reef to eastward could not be the work of men but must be something supernatural. This had quenched in them all desire to go across and see for themselves. But then part of a box had come drifting across the lagoon, and on it some signs were painted. Two of the natives, who had been on Tahiti and learned the alphabet, had deciphered the inscription and read TIKI in big black letters on the slab of wood. Then there was no longer any doubt that there were ghosts on the reef, for Tiki was the long-dead founder of their own race—they all knew that. But then tinned bread, cigarettes, cocoa, and a box with an old shoe in it came drifting across the lagoon. Now they all realized that there had been a shipwreck on the eastern side of the reef, and the chief sent out two canoes to search for the survivors whose fire they had seen on the island.

Urged on by the others, the brown man who spoke French asked why the slab of wood that drifted across the lagoon had “Tiki” on it. We explained that “Kon-Tiki” was on all our equipment and that it was the name of the vessel in which we had come.

Our new friends were loud in their astonishment when they heard that all on board had been saved, when the vessel stranded, and that the flattened wreck out on the reef was actually the craft in which we had come. They wanted to put us all into the canoes at once and take us across to the village. We thanked them and refused, as we wanted to stay till we had got the Kon-Tiki off the reef. They looked aghast at the flat contraption out on the reef; surely we could not dream of getting that collapsed hull afloat again! Finally the spokesman said emphatically that we must go with them; the chief had given them strict orders not to return without us.

We then decided that one of us should go with the natives as envoy to the chief and should then come back and report to us on the conditions on the other island. We would not let the raft remain on the reef and could not abandon all the equipment on our little island. Bengt went with the natives. The two canoes were pushed off from the sand and soon disappeared westward with a fair wind.

Next day the horizon swarmed with white sails. Now, it seemed, the natives were coming to fetch us with all the craft they had.

The whole convoy tacked across toward us, and, when they came near, we saw our good friend Bengt waving his hat in the first canoe, surrounded by brown figures. He shouted to us that the chief himself was with him, and the five of us formed up respectfully down on the beach where they were wading ashore.

Bengt presented us to the chief with great ceremony. The chief’s name, Bengt said, was Tepiuraiarii Teriifaatau, but he would understand whom we meant if we called him Teka. We called him Teka.

Teka was a tall, slender Polynesian with uncommonly intelligent eyes. He was an important person, a descendant of the old royal line in Tahiti, and was chief of both the Raroia and the Takume islands. He had been to school in Tahiti, so that he spoke French and could both read and write. He told me that the capital of Norway was called Christiania and asked if I knew Bing Crosby. He also told us that only three foreign vessels had called at Raroia in the last ten years, but that the village was visited several times a year by the native copra schooner from Tahiti, which brought merchandise and took away coconut kernels in exchange. They had been expecting the schooner for some weeks now, so she might come at any time.

Bengt’s report, summarized, was that there was no school, radio, or any white men on Raroia, but that the 127 Polynesians in the village had done all they could to make us comfortable there and had prepared a great reception for us when we came over.

The chief’s first request was to see the boat which had brought us ashore on the reef alive. We waded out toward the Kon-Tiki with a string of natives after us. When we drew near, the natives suddenly stopped and uttered loud exclamations, all talking at once. We could now see the logs of the Kon-Tiki plainly, and one of the natives burst out:

“That’s not a boat, it’s a pae-pae!”

“Pae-pae!” they all repeated in chorus.

They splashed out across the reef at a gallop and clambered up on to the Kon-Tiki. They scrambled about everywhere like excited children, feeling the logs, the bamboo plaiting, and the ropes. The chief was in as high spirits as the others; he came back and repeated with an inquiring expression:

“The Tiki isn’t a boat, she’s a pae-pae.”

Pae-pae is the Polynesian word for “raft” and “platform,” and on Easter Island it is also the word used for the natives’ canoes. The chief told us that such pae-pae no longer existed, but that the oldest men in the village could relate old traditions of them. The natives all outshouted one another in admiration for the great balsa logs, but they turned up their noses at the ropes. Ropes like that did not last many months in salt water and sun. They showed us with pride the lashings on their own outriggers; they had plaited them themselves of coconut hemp, and such ropes remained as good as new for five years at sea.

When we waded back to our little island, it was named Fenua Kon-Tiki, or Kon-Tiki Island. This was a name we could all pronounce, but our brown friends had a hard job trying to pronounce our short Nordic Christian names. They were delighted when I said they could call me Terai Mateata, for the great chief in Tahiti had given me that name when adopting me as his “son” the first time I was in those parts.

The natives brought out fowls and eggs and breadfruit from the canoes, while others speared big fish in the lagoon with three-pronged spears, and we had a feast round the campfire. We had to narrate all our experiences with the pae-pae at sea, and they wanted to hear about the whale shark again and again. And every time we came to the point at which Erik rammed the harpoon into its skull, they uttered the same cries of excitement. They recognized at once every single fish of which we showed them sketches and promptly gave us the names in Polynesian. But they had never seen or heard of the whale shark or the Gempylus.

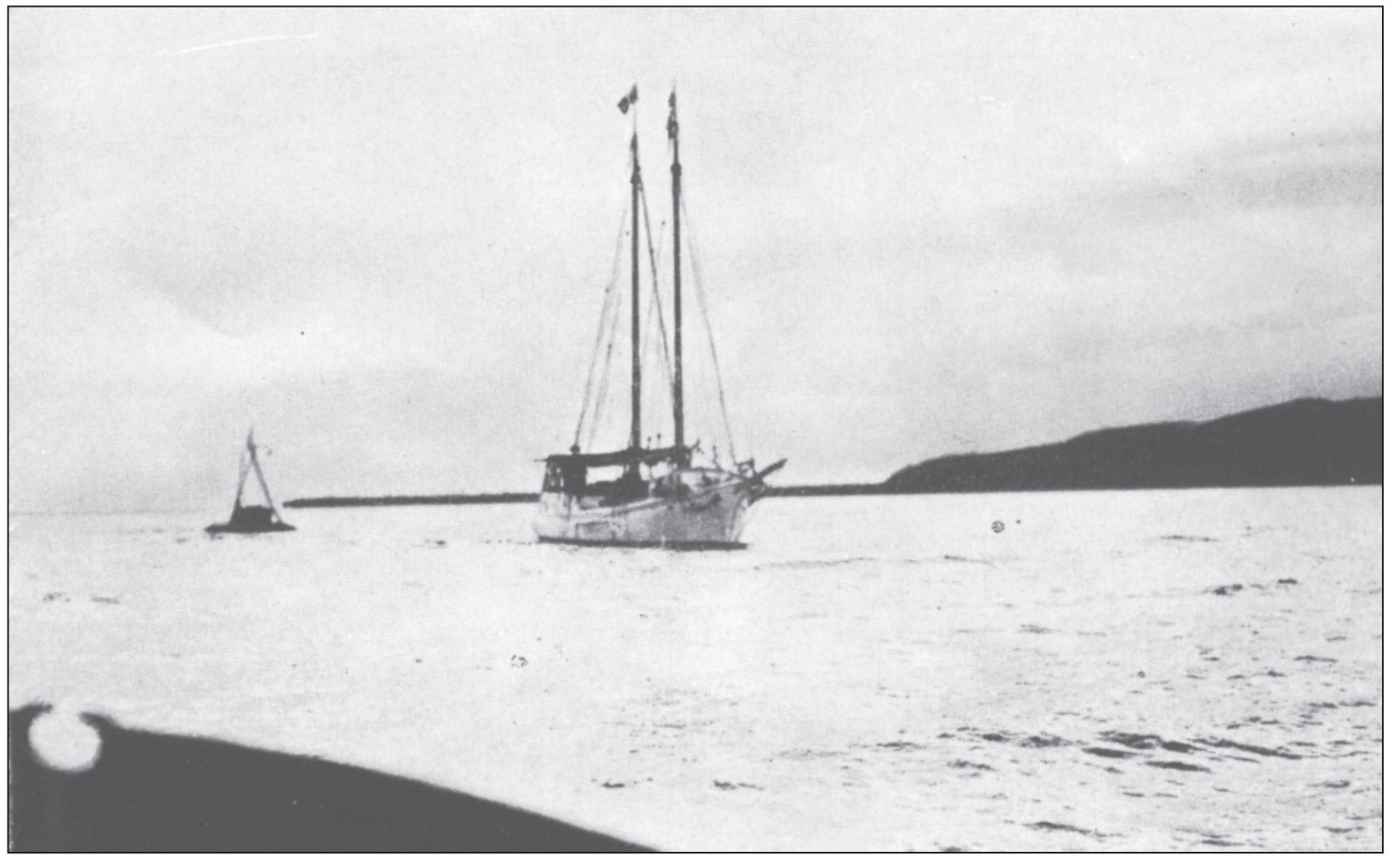

The raft arrives at Tahiti in tow of the government schooner “Tamara.”

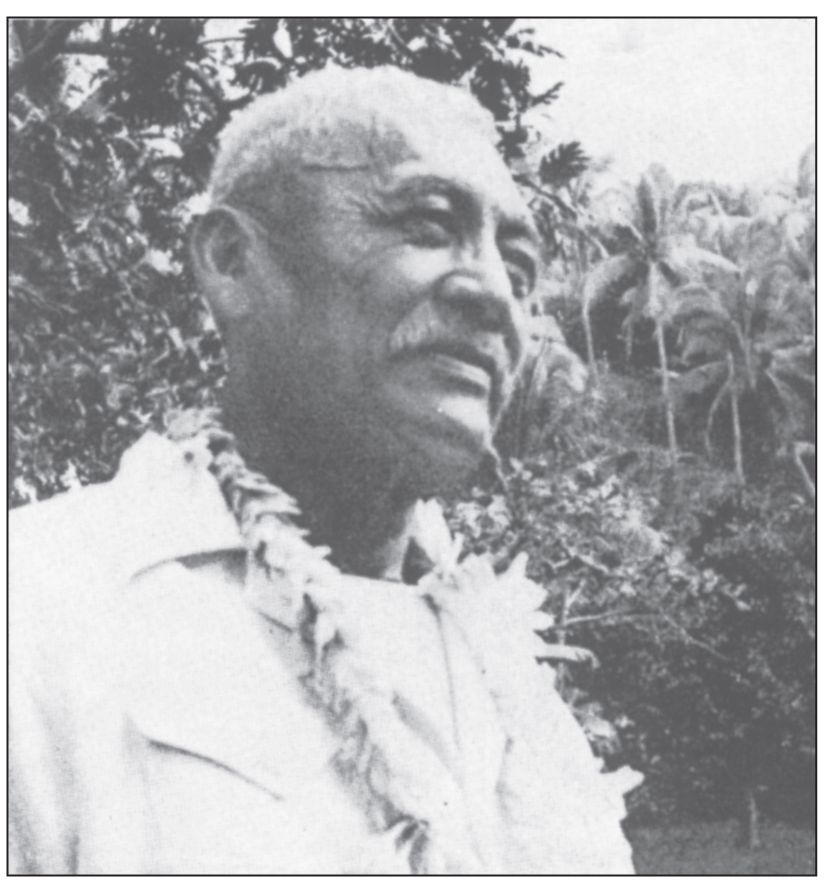

Teriieroo a Teriierooiterai is the name of the last chief on Tahiti. He was on the quay to meet us when we arrived. Ten years before he had adopted the author as his son and had given him the name Terai Mateata (Blue Sky).

Tiki was the name of the first great chief on Tahiti. He was regarded by the inhabitants as their divine ancestor, and stone statues of South American type were erected in his honor on many of the islands.

The country which Tiki found. Low coral islands, like those of the Tuamotu group, and lofty mountainous islands like Tahiti and Moorea were found by Kon-Tiki, Son of the Sun, when he came from Peru with the first men on balsa rafts.

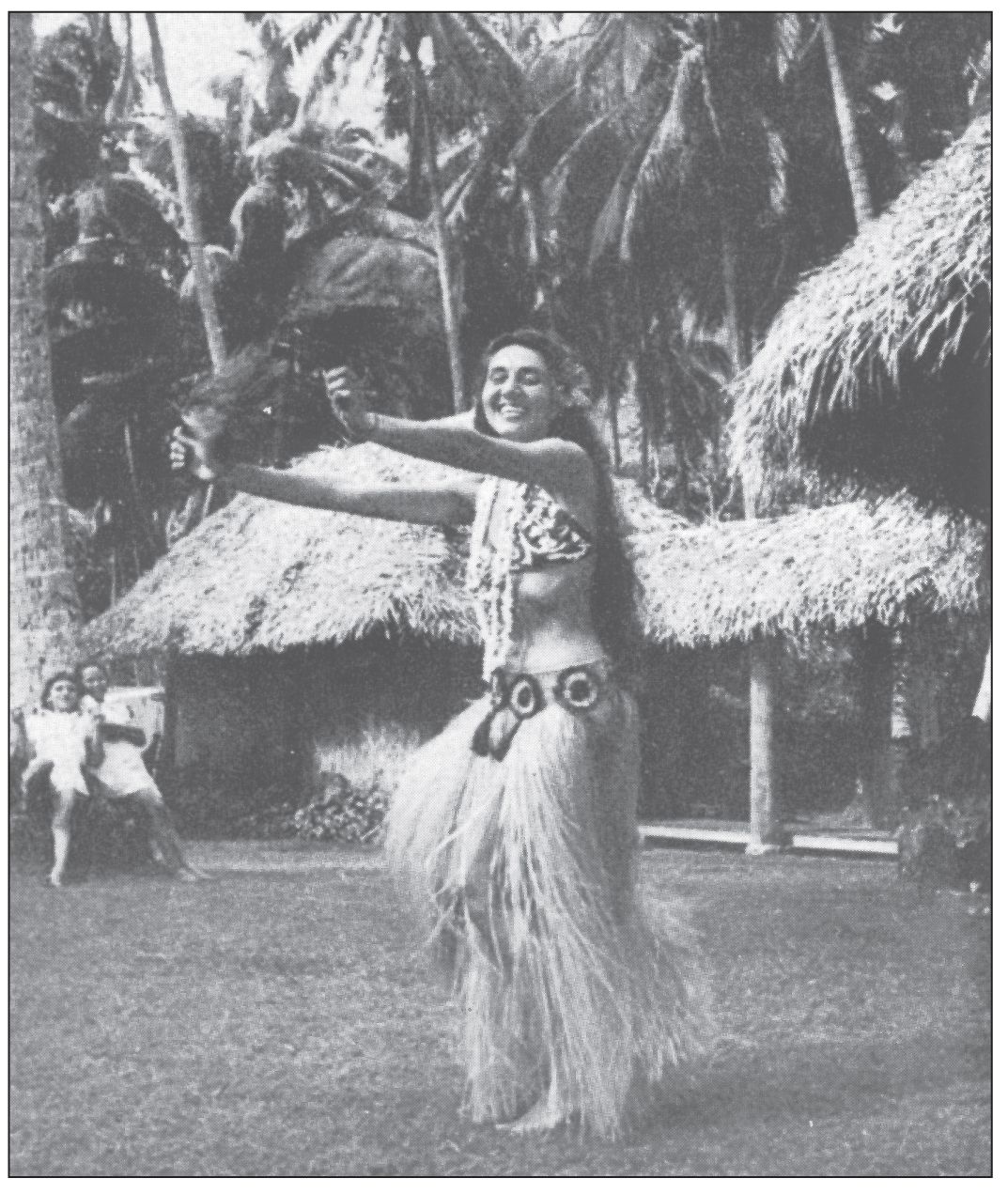

Hula dance on Tahiti. Purea was related to the last queen of the island. After Tiki another Indian race came to these islands in big double canoes from British Columbia via Hawaii. The Polynesian race is a mixture of these two immigrant peoples.

A Tahitian belle. When we came to the native village on Raroia, the natives started festivities that lasted the fourteen days we spent on the island. Our stay on Tahiti was of the same nature, but lasted longer.

At the White House. After our return to Washington, President Truman received the members of the expedition. The American flag that had accompanied us across the Pacific was presented to him. From left: (half hidden) Knut Haugland, the author, Herman Watzinger, President Truman, Mr. Lykke (counselor to the Embassy), Erik Hesselberg, and Torstein Raaby. Bengt Danielsson had remained on the west coast.

When the evening came, we turned on the radio, to the great delight of the whole assemblage. Church music was most to their taste until, to our own astonishment, we picked up real hula music from America. Then the liveliest of them began to wriggle with their arms curved over their heads, and soon the whole company sprang up on their haunches and danced the hula-hula in time with the music. When night came, all camped round a fire on the beach. It was as much of an adventure to the natives as it was to us.

When we awoke next morning, they were already up and frying newly caught fish, while six freshly opened coconut shells stood ready for us to quench our morning thirst.

The reef was thundering more than usual that day; the wind had increased in strength, and the surf was whipping high into the air out there behind the wreck.

“The Tiki will come in today,” said the chief, pointing to the wreck. “There’ll be a high tide.”

About eleven o’clock the water began to flow past us into the lagoon. The lagoon began to fill like a big basin, and the water rose all round the island. Later in the day the real inflow from the sea came. The water came rolling in, terrace after terrace, and more and more of the reef sank below the surface of the sea. The masses of water rolled forward along both sides of the island. They tore away large coral blocks and dug up great sandbanks which disappeared like flour before the wind, while others were built up. Loose bamboos from the wreck came sailing past us, and the Kon-Tiki began to move. Everything that was lying along the beach had to be carried up into the interior of the island so that it might not be caught by the tide. Soon only the highest stones on the reef were visible, and all the beaches round our island had gone, while the water flowed up toward the herbage of the pancake island. This was eerie. It looked as if the whole sea were invading us. The Kon-Tiki swung right round and drifted until she was caught by some other coral blocks.

The natives flung themselves into the water and swam and waded through the eddies till, moving from bank to bank, they reached the raft. Knut and Erik followed. Ropes lay ready on board the raft, and, when she rolled over the last coral blocks and broke loose from the reef, the natives jumped overboard and tried to hold her. They did not know the Kon-Tiki and her ungovernable urge to push on westward; so they were towed along helplessly with her. She was soon moving at a good speed right across the reef and into the lagoon. She became slightly at a loss when she reached quieter water and seemed to be looking round as though to obtain a survey of further possibilities. Before she began to move again and discovered the exit across the lagoon, the natives had already succeeded in getting the end of the rope around a palm on land. And there the Kon-Tiki hung, tied up fast in the lagoon. The craft that went over land and water had made her way across the barricade and into the lagoon in the interior of Raroia.

With inspiring war cries, to which “ke-ke-te-huru-huru” formed an animating refrain, we hauled the Kon-Tiki by our combined efforts in to the shore of the island of her own name. The tide reached a point four feet above normal high water. We had thought the whole island was going to disappear before our eyes.

The wind-whipped waves were breaking all over the lagoon, and we could not get much of our equipment into the narrow, wet canoes. The natives had to get back to the village in a hurry, and Bengt and Herman went with them to see a small boy who lay dying in a hut in the village. The boy had an abscess on his head, and we had penicillin.

Next day we four were alone on Kon-Tiki Island. The east wind was now so strong that the natives could not come across the lagoon, which was studded with sharp coral formations and shoals. The tide, which had somewhat receded, flowed in again fiercely, in long, rushing step formations.

Next day it was quieter again. We were now able to dive under the Kon-Tiki and ascertain that the nine logs were intact, even if the reef had planed an inch or two off the bottom. The cordage lay so deep in its grooves that only four of the numerous ropes had been cut by the corals. We set about clearing up on board. Our proud vessel looked better when the mess had been removed from the deck, the cabin pulled out again like a concertina, and the mast spliced and set upright.

In the course of the day the sails appeared on the horizon again; the natives were coming to fetch us and the rest of the cargo. Herman and Bengt were with them, and they told us that the natives had prepared great festivities in the village. When we got over to the other island, we must not leave the canoes till the chief himself had indicated that we might do so.

We ran across the lagoon, which here was seven miles wide, before a fresh breeze. It was with real sorrow that we saw the familiar palms on Kon-Tiki Island waving us good-by as they changed into a clump and shrank into one small indefinable island like all the others along the eastern reef. But ahead of us larger islands were broadening out. And on one of them we saw a jetty and smoke rising from huts among the palm trunks.

The village looked quite dead; not a soul was to be seen. What was brewing now? Down on the beach, behind a jetty of coral blocks, stood two solitary figures, one tall and thin and one big and stout as a barrel. As we came in, we saluted them both. They were the chief Teka and the vice-chief Tupuhoe. We all fell for Tupuhoe’s broad hearty smile. Teka was a clear brain and a diplomat, but Tupuhoe was a pure child of nature and a sterling fellow, with a humor and a primitive force the like of which one meets but rarely. With his powerful body and kingly features he was exactly what one expects a Polynesian chief to be. Tupuhoe was, indeed, the real chief on the island, but Teka had gradually acquired the supreme position because he could speak French and count and write, so that the village was not cheated when the schooner came from Tahiti to fetch copra.

Teka explained that we were to march together up to the meetinghouse in the village, and when all the boys had come ashore we set off thither in ceremonial procession, Herman first with the flag waving on a harpoon shaft, and then I myself between the two chiefs.

The village bore obvious marks of the copra trade with Tahiti; both planks and corrugated iron had been imported in the schooner. While some huts were built in a picturesque old-fashioned style, with twigs and plaited palm leaves, others were knocked together with nails and planks as small tropical bungalows. A large house built of planks, standing alone among the palms, was the new village meetinghouse; there we six whites were to stay. We marched in with the flag by a small back door and out on to a broad flight of steps before the façade. Before us in the square stood everyone in the village who could walk or crawl—women and children, old and young. All were intensely serious; even our cheerful friends from Kon-Tiki Island stood drawn up among the others and did not give us a sign of recognition.

When we had all come out on the steps, the whole assembly opened their mouths simultaneously and joined in singing—the “Marseillaise”! Teka, who knew the words, led the singing, and it went fairly well in spite of a few old women getting stuck up on the high notes. They had been training hard for this. The French and Norwegian flags were hoisted in front of the steps, and this ended the official reception by the chief Teka. He retired quietly into the background, and now stout Tupuhoe sprang forward and became master of the ceremonies. Tupuhoe gave a quick sign, on which the whole assembly burst into a new song. This time it went better, for the tune was composed by themselves and the words, too, were in their language—and sing their own hula they could. The melody was so fascinating, in all its touching simplicity, that we felt a tingling down our backs as the South Sea came roaring toward us. A few individuals led the singing and the whole choir joined in regularly; there were variations in the melody, though the words were always the same:

“Good day, Terai Mateata and your men, who have come across the sea on a pae-pae to us on Raroia; yes, good day, may you remain long among us and share memories with us so that we can always be together, even when you go away to a far land. Good day.”

We had to ask them to sing the song over again, and more and more life came into the whole assembly as they began to feel less constrained. Then Tupuhoe asked me to say a few words to the people as to why we had come across the sea on a pae-pae; they had all been counting on this. I was to speak in French, and Teka would translate bit by bit.

It was an uneducated but highly intelligent gathering of brown people that stood waiting for me to speak. I told them that I had been among their kinsmen out here in the South Sea islands before, and that I had heard of their first chief, Tiki, who had brought their forefathers out to the islands from a mysterious country whose whereabouts no one knew any longer. But in a distant land called Peru, I said, a mighty chief had once ruled whose name was Tiki. The people called him Kon-Tiki, or Sun-Tiki, because he said he was descended from the sun. Tiki and a number of followers had at last disappeared from their country on big pae-paes; therefore we six thought that he was the same Tiki who had come to those islands. As nobody would believe that a pae-pae could make the voyage across the sea, we ourselves had set out from Peru on a pae-pae, and here we were, so it could be done.

When the little speech was translated by Teka, Tupuhoe was all fire and flame and sprang forward in front of the assembly in a kind of ecstasy. He rumbled away in Polynesian, flung out his arms, pointed to heaven and us, and in his flood of speech constantly repeated the word Tiki. He talked so fast that it was impossible to follow the thread of what he said, but the whole assembly swallowed every word and was visibly excited. Teka, on the contrary, looked quite embarrassed when he had to translate.

Tupuhoe had said that his father and grandfather, and his fathers before him, had told of Tiki and had said that Tiki was their first chief who was now in heaven. But then the white men came and said that the traditions of their ancestors were lies. Tiki had never existed. He was not in heaven at all, for Jehovah was there. Tiki was a heathen god, and they must not believe in him any longer. But now we six had come to them across the sea on a pae-pae. We were the first whites who had admitted that their fathers had spoken the truth. Tiki had lived, he had been real, but now he was dead and in heaven.

Horrified at the thought of upsetting the missionaries’ work, I had to hurry forward and explain that Tiki had lived, that was sure and certain, and now he was dead. But whether he was in heaven or in hell today only Jehovah knew, for Jehovah was in heaven while Tiki himself had been a mortal man, a great chief like Teka and Tupuhoe, perhaps still greater.

This produced both cheerfulness and contentment among the brown men, and the nodding and mumbling among them showed clearly that the explanation had fallen on good soil. Tiki had lived—that was the main thing. If he was in hell now, no one was any the worse for it but himself; on the contrary, Tupuhoe suggested, perhaps it increased the chances of seeing him again.

Three old men pushed forward and wanted to shake hands with us. There was no doubt that it was they who had kept the memories of Tiki alive among the people, and the chief told us that one of the old men knew an immense number of traditions and historical ballads from his forefathers’ time. I asked the old man if there was, in the traditions, any hint of the direction from which Tiki had come. No, none of the old men could remember having heard that. But after long and careful reflection the oldest of the three said that Tiki had with him a near relation who was called Maui, and in the ballad of Maui it was said that he had come to the islands from Pura and pura was the word for the part of the sky where the sun rose. If Maui had come from Pura, the old man said, Tiki had no doubt come from the same place, and we six on the pae-pae had also come from pura—that was sure enough.

I told the brown men that on a lonely island near Easter Island, called Mangareva, the people had never learned the use of canoes and had continued to use big pae-paes at sea right down to our time. This the old men did not know, but they knew that their forefathers also had used big pae-paes. However, they had gradually gone out of use, and now they had nothing but the name and traditions left. In really ancient times they had been called rongo-rongo, the oldest man said, but that was a word which no longer existed in the language. Rongo-rongo were mentioned in the most ancient legends.

This name was interesting, for Rongo—on certain islands pronounced “Lono”—was the name of one of the Polynesians’ best-known legendary ancestors. He was expressly described as white and fair-haired. When Captain Cook first came to Hawaii, he was received with open arms by the islanders because they thought he was their white kinsman Rongo, who, after an absence of generations, had come back from their ancestors’ homeland in his big sailing ship. And on Easter Island the word “rongo-rongo” was the designation for the mysterious hieroglyphs the secret of which was lost with the last “long-ears” who could write.

While the old men wanted to discuss Tiki and rongo-rongo, the young ones wanted to hear about the whale shark and the voyage across the sea. But the food was waiting, and Teka was tired of interpreting.

Now the whole village was allowed to come up and shake hands with each of us. The men mumbled “ia-ora-na” and almost shook our hands out of joint, while the girls squirmed forward and greeted us coquettishly yet shyly and the old women babbled and cackled and pointed to our beards and the color of our skin. Friendliness beamed from every face, so it was quite immaterial that there was a hubbub of linguistic confusion. If they said something incomprehensible to us in Polynesian, we gave them tit for tat in Norwegian. We had the greatest fun together. The first native word we all learned was the word for “like,” and when, moreover, one could point to what one liked and count on getting it at once, it was all very simple. If one wrinkled one’s nose when “like” was said, it meant “don’t like,” and on this basis we got along pretty well.

As soon as we had become acquainted with the 127 inhabitants of the village, a long table was laid for the two chiefs and the six of us, and the village girls came round bearing the most delicious dishes. While some arranged the table, others came and hung plaited wreaths of flowers round our necks and smaller wreaths round our heads. These exhaled a lingering scent and were cool and refreshing in the heat. And so a feast of welcome began which did not end till we left the island weeks after. Our eyes opened wide and our mouths watered, for the tables were loaded with roast suckling pigs, chickens, roast ducks, fresh lobsters, Polynesian fish dishes, breadfruit, papaya, and coconut milk. While we attacked the dishes, we were entertained by the crowd singing hula songs, while young girls danced round the table.

The boys laughed and thoroughly enjoyed themselves, each of us looking more absurd than the next as we sat and gorged like starving men, with flowing beards and wreaths of flowers in our hair. The two chiefs were enjoying life as wholeheartedly as ourselves.

After the meal there was hula dancing on a grand scale. The village wanted to show us their local folk dances. While we six and Teka and Tupuhoe were each given stools in the orchestra, two guitar players advanced, squatted down, and began to strum real South Sea melodies. Two ranks of dancing men and women, with rustling skirts of palm leaves round their hips, came gliding and wriggling forward through the ring of spectators who squatted and sang. They had a lively and spirited leading singer in a luxuriantly fat vahine, who had had one arm bitten off by a shark. At first the dancers seemed a little self-conscious and nervous, but when they saw that the white men from the pae-pae did not turn up their noses at their ancestors’ folk dances, the dancing became more and more animated. Some of the older people joined in; they had a splendid rhythm and could dance dances which were obviously no longer in common use. As the sun sank into the Pacific, the dancing under the palm trees became livelier and livelier, and the applause of the spectators more and more spontaneous. They had forgotten that we who sat watching them were six strangers; we were now six of their own people, enjoying ourselves with them.

The repertory was endless; one fascinating display followed another. Finally a crowd of young men squatted down in a close ring just in front of us, and at a sign from Tupuhoe they began to beat time rhythmically on the ground with the palms of their hands. First slowly, then more quickly, and the rhythm grew more and more perfect when a drummer suddenly joined in and accompanied them, beating at a furious pace with two sticks on a bone-dry, hollowed block of wood which emitted a sharp, intense sound. When the rhythm reached the desired degree of animation, the singing began, and suddenly a hula girl with a wreath of flowers round her neck and flowers behind one ear leaped into the ring. She kept time to the music with bare feet and bent knees, swaying rhythmically at the hips and curving her arms above her head in true Polynesian style. She danced splendidly, and soon the whole assembly were beating time with their hands. Another girl leaped into the ring, and after her another. They moved with incredible suppleness in perfect rhythm, gliding round one another in the dance like graceful shadows. The dull beating of hands on the ground, the singing, and the cheerful wooden drum increased their tempo faster and faster and the dance grew wilder and wilder, while the spectators howled and clapped in perfect rhythm.

This was the South Seas life as the old days had known it. The stars twinkled and the palms waved. The night was mild and long and full of the scent of flowers and the song of crickets. Tupuhoe beamed and slapped me on the shoulder. “Maitai?” he asked.

“Yes, maitai,” I replied.

“Maitai?” he asked all the others.

“Maitai,” they all replied emphatically, and they all really meant it.

“Maitai,” Tupuhoe nodded, pointing to himself; he too was enjoying himself now.

Even Teka thought it was a very good feast; it was the first time white men had been present at their dances on Raroia, he said. Faster and faster, faster and faster, went the rolls of the drums, the clapping, singing, and dancing. Now one of the girl dancers ceased to move round the ring and remained on the same spot, performing a wriggling dance at a terrific tempo with her arms stretched out toward Herman. Herman snickered behind his beard; he did not quite know how to take it. “Be a good sport,” I whispered. “You’re a good dancer.”

To the boundless delight of the crowd Herman sprang into the ring and, half crouching, tackled all the difficult wriggling movements of the hula. The jubilation was unbounded. Soon Bengt and Torstein leaped into the dance, striving till the perspiration streamed down their faces to keep up with the tempo, which rose and rose to a furious pace till the drum alone was beating in one prolonged drone and the three real hula dancers quivering in time like aspen leaves. Then they sank down in the finales and the drumbeats ceased abruptly.

Now the evening was ours. There was no end to the enthusiasm.

The next item on the program was the bird dance, which was one of the oldest ceremonies on Raroia. Men and women in two ranks jumped forward in a rhythmic dance, imitating flocks of birds following a leader. The dance leader had the title of chief of the birds and performed curious maneuvers without actually joining in the dance. When the dance was over, Tupuhoe explained that it had been performed in honor of the raft and would now be repeated, but the dance leader would be relieved by myself. As the dance leader’s main task appeared to me to consist in uttering wild howls, hopping around on his haunches, wriggling his backside, and waving his hands over his head, I pulled the wreath of flowers well down over my head and marched out into the arena. While I was curving myself in the dance, I saw old Tupuhoe laughing till he nearly fell off his stool, and the music grew feeble because the singers and players followed Tupuhoe’s example.

Now everyone wanted to dance, old and young alike, and soon the drummer and earth-beaters were there again, giving the lead to a fiery hula-hula dance. First the hula girls sprang into the ring and started the dance at a tempo that grew wilder and wilder, and then we were invited to dance in turn, while more and more men and women followed, stamping and writhing along, faster and faster.

But Erik could not be made to stir. The drafts and damp on board the raft had revived his vanished lumbago and he sat like an old yacht skipper, stiff and bearded, puffing at his pipe. He would not be moved by the hula girls who tried to lure him into the arena. He had put on a pair of wide sheepskin trousers which he had worn at night in the coldest spells in the Humboldt Current, and, sitting under the palms with his big beard, body bare to the waist, and sheepskin breeches, he was a faithful copy of Robinson Crusoe. One pretty girl after another tried to ingratiate herself, but in vain. He only sat gravely puffing his pipe, with the wreath of flowers in his bushy hair.

Then a well-developed matron with powerful muscles entered the arena, executed a few more or less graceful hula steps, and then marched determinedly toward Erik. He looked alarmed, but the amazon smiled ingratiatingly, caught him resolutely by the arm, and pulled him off of his stool. Erik’s comic pair of breeches had the sheep’s wool inside and the skin outside, and they had a rent behind so that a white spot of wool stuck out like a rabbit’s tail. Erik followed most reluctantly and limped into the ring with his pipe in one hand and the other pressed against the spot where his lumbago hurt him. When he tried to jump round, he had to let go of his trousers to save his wreath which was threatening to fall off, and then, with the wreath on one side, he had to catch hold of his trousers again, which were coming down of their own weight. The stout dame who was hobbling round in the hula in front of him was just as funny, and tears of laughter trickled down our beards. Soon all the others who were in the ring stopped, and salvos of laughter rang through the palm grove as Hula Erik and the female heavyweight circled gracefully round. At last even they had to stop, because both singers and musicians had more than they could do to hold their sides for laughter at the comic sight.

The feast went on till broad daylight, when we were allowed to have a little pause, after again shaking hands with every one of the 127. We shook hands with every one of them every morning and every evening throughout our stay on the island. Six beds were scraped together from all the huts in the village and placed side by side along the wall in the meetinghouse, and in these we slept in a row like the seven little dwarfs in the fairy story, with sweet-smelling wreaths of flowers hanging above our heads.

Next day the boy of six who had an abscess on his head seemed to be in a bad way. He had a temperature of 106°, and the abscess was as large as a man’s fist and throbbed painfully.

Teka declared that they had lost a number of children in this way and that, if none of us could do any doctoring, the boy had not many days to live. We had bottles of penicillin in a new tablet form, but we did not know what dose a small child could stand. If the boy died under our treatment, it might have serious consequences for all of us.

Knut and Torstein got the radio out again and slung up an aerial between the tallest coconut palms. When evening came they got in touch again with our unseen friends, Hal and Frank, sitting in their rooms at home in Los Angeles. Frank called a doctor on the telephone, and we signaled with the Morse key all the boy’s symptoms and a list of what we had available in our medical chest. Frank passed on the doctor’s reply, and that night we went off to the hut where little Haumata lay tossing in a fever with half the village weeping and making a noise about him.

Herman and Knut were to do the doctoring, while we others had more than enough to do to keep the villagers outside. The mother became hysterical when we came with a sharp knife and asked for boiling water. All the hair was shaved off the boy’s head and the abscess was opened. The pus squirted up almost to the roof, and several of the natives forced their way in in a state of fury and had to be turned out. It was a grave moment. When the abscess was drained and sterilized, the boy’s head was bound up and we began the penicillin cure. For two days and nights, while the fever was at its maximum, the boy was treated every four hours, and the abscess was kept open. And each evening the doctor in Los Angeles was consulted. Then the boy’s temperature fell suddenly, the pus was replaced by plasma which was allowed to heal, and the boy was beaming and wanting to look at pictures from the white man’s strange world where there were motorcars and cows and houses with several floors.

A week later Haumata was playing on the beach with the other children, his head bound up in a big bandage which he was soon allowed to take off.

When this had gone well, there was no end to the maladies which cropped up in the village. Toothache and gastric troubles were everywhere, and both old and young had boils in one place or another. We referred the patients to Dr. Knut and Dr. Herman, who ordered diets and emptied the medicine chest of pills and ointments. Some were cured and none became worse, and, when the medicine chest was empty, we made oatmeal porridge and cocoa, which were admirably efficacious with hysterical women.

We had not been among our brown admirers for many days before the festivities culminated in a fresh ceremony. We were to be adopted as citizens of Raroia and receive Polynesian names. I myself was no longer to be Terai Mateata; I could be called that in Tahiti, but not here among them.

Six stools were placed for us in the middle of the square, and the whole village was out early to get good places in the circle round. Teka sat solemnly among them; he was chief all right, but not where old local ceremonies were concerned. Then Tupuhoe took over.

All sat waiting, silent and profoundly serious, while portly Tupuhoe approached solemnly and slowly with his stout knotted stick. He was conscious of the gravity of the moment, and the eyes of all were upon him as he came up, deep in thought, and took up his position in front of us. He was the born chief—a brilliant speaker and actor.

He turned to the chief singers, drummers, and dance leaders, pointed at them in turn with his knotted stick, and gave them curt orders in low, measured tones. Then he turned to us again, and suddenly opened his great eyes wide, so that the large white eyeballs shone as bright as the teeth in his expressive copper-brown face. He raised the knotted stick and, the words streaming from his lips in an uninterrupted flow, he recited ancient rituals which none but the oldest members understood, because they were in an old forgotten dialect.

Then he told us, with Teka as interpreter, that Tikaroa was the name of the first king who had established himself on the island, and that he had reigned over this same atoll from north to south, from east to west, and up into the sky above men’s heads.

While the whole choir joined in the old ballad about King Tikaroa, Tupuhoe laid his great hand on my chest and, turning to the audience, said that he was naming me Varoa Tikaroa, or Tikaroa’s Spirit.

When the song died away, it was the turn of Herman and Bengt. They had the big brown hand laid upon their chests in turn and received the names Tupuhoe-Itetahua and Topakino. These were the names of two old-time heroes who had fought a savage sea monster and killed it at the entrance to the Raroia reef.

The drummer delivered a few vigorous rolls, and two robust men with knotted-up loincloths and a long spear in each hand sprang forward. They broke into a march in double-quick time, with their knees raised to their chests and their spears pointing upward, and turned their heads from side to side. At a fresh beat of the drum they leaped into the air and, in perfect rhythm, began a ceremonial battle in the purest ballet style. The whole thing was short and swift and represented the heroes’ fight with the sea monster. Then Torstein was named with song and ceremony ; he was called Maroake, after a former king in the present village, and Erik and Knut received the names of Tane-Matarau and Tefaunui after two navigators and sea heroes of the past. The long monotonous recitation which accompanied their naming was delivered at breakneck speed and with a continuous flow of words, the incredible rapidity of which was calculated both to impress and amuse.

The ceremony was over. Once more there were white and bearded chiefs among the Polynesian people on Raroia. Two ranks of male and female dancers came forward in plaited straw skirts with swaying bast crowns on their heads. They danced forward to us and transferred the crowns from their own heads to ours; we had rustling straw skirts put round our waists, and the festivities continued.

One night the flower-clad radio operators got into touch with the radio amateur on Rarotonga, who passed on a message to us from Tahiti. It was a cordial welcome from the governor of the French Pacific colonies.

On instructions from Paris he had sent the government schooner “Tamara” to fetch us to Tahiti, so we should not have to wait for the uncertain arrival of the copra schooner. Tahiti was the central point of the French colonies and the only island which had contact with the world in general. We should have to go via Tahiti to get the regular boat home to our own world.

The festivities continued on Raroia. One night some strange hoots were heard from out at sea, and lookout men came down from the palm tops and reported that a vessel was lying at the entrance to the lagoon. We ran through the palm forest and down to the beach on the lee side. Here we looked out over the sea in the opposite direction to that from which we had come. There were much smaller breakers on this side, which lay under the shelter of the entire atoll and the reef.

Just outside the entrance to the lagoon we saw the lights of a vessel. Since the night was clear and starry, we could distinguish the outlines of a broad-beamed schooner with two masts. Was this the governor’s ship which was coming for us? Why did she not come in?

The natives grew more and more uneasy. Now we too saw what was happening. The vessel had a heavy list and threatened to capsize. She was aground on an invisible coral reef under the surface.

Torstein got hold of a light and signaled:

“Quel bateau?”

“ ‘Maoae,’ ” was flashed back.

The “Maoae” was the copra schooner which ran between the islands. She was on her way to Raroia to fetch copra. There was a Polynesian captain and crew on board, and they knew the reefs inside out. But the current out of the lagoon was treacherous in darkness. It was lucky that the schooner lay under the lee of the island and that the weather was quiet. The list of the “Maoae” became heavier and heavier, and the crew took to the boat. Strong ropes were made fast to her mastheads and rowed in to the land, where the natives fastened them round coconut palms to prevent the schooner from capsizing. The crew, with other ropes, stationed themselves off the opening in the reef in their boat, in the hope of rowing the “Maoae” off when the tidal current ran out of the lagoon. The people of the village launched all their canoes and set out to salvage the cargo. There were ninety tons of valuable copra on board. Load after load of sacks of copra was transferred from the rolling schooner and brought on to dry land.

At high water the “Maoae” was still aground, bumping and rolling against the corals until she sprang a leak. When day broke she was lying in a worse position on the reef than ever. The crew could do nothing; it was useless to try to haul the heavy 150-ton schooner off the reef with her own boat and the canoes. If she continued to lie bumping where she was, she would knock herself to pieces, and, if the weather changed, she would be lifted in by the suction and be a total loss in the surf which beat against the atoll.

The “Maoae” had no radio, but we had. But it would be impossible to get a salvage vessel from Tahiti until the “Maoae” would have had ample time to roll herself into wreckage. Yet for the second time that month the Raroia reef was balked of its prey.

About noon the same day the schooner “Tamara” came in sight on the horizon to westward. She had been sent to fetch us from Raroia, and those on board were not a little astonished when they saw, instead of a raft, the two masts of a large schooner lying and rolling helplessly on the reef.

On board the “Tamara” was the French administrator of the Tuamotu and Tubuai groups, M. Frédéric Ahnne, whom the governor had sent with the vessel from Tahiti to meet us. There were also a French movie photographer and a French telegrapher on board, but the captain and crew were Polynesian. M. Ahnne himself had been born in Tahiti of French parents and was a splendid seaman. He took over the command of the vessel with the consent of the Tahitian captain, who was delighted to be freed from the responsibility in those dangerous waters. While the “Tamara” was avoiding a myriad of submerged reefs and eddies, stout hawsers were stretched between the two schooners and M. Ahnne began his skillful and dangerous evolutions, while the tide threatened to drag both vessels on to the same coral bank.

At high tide the “Maoae” came off the reef, and the “Tamara” towed her out into deep water. But now water poured through the hull of the “Maoae,” and she had to be hauled with all speed on to the shallows in the lagoon. For three days the “Maoae” lay off the village in a sinking condition, with all pumps going day and night. The best pearl divers among our friends on the island went down with lead plates and nails and stopped the worst leaks, so that the “Maoae” could be escorted by the “Tamara” to the dockyard in Tahiti with her pumps working.

When the “Maoae” was ready to be escorted, M. Ahnne maneuvered the “Tamara” between the coral shallows in the lagoon and across to Kon-Tiki Island. The raft was taken in tow, and then he set his course back to the opening with the Kon-Tiki in tow and the “Maoae” so close behind that the crew could be taken off if the leaks got the upper hand out at sea.

Our farewell to Raroia was more than sad. Everyone who could walk or crawl was down on the jetty, playing and singing our favorite tunes as the ship’s boat took us out to the “Tamara.”

Tupuhoe bulked large in the center, holding little Haumata by the hand. Haumata was crying, and tears trickled down the cheeks of the powerful chief. There was not a dry eye on the jetty, but they kept the singing and music going long, long after the breakers from the reef drowned all other sounds in our ears.

Those faithful souls who stood on the jetty singing were losing six friends. We who stood mute at the rail of the “Tamara” till the jetty was hidden by the palms and the palms sank into the sea were losing 127. We still heard the strange music with our inner ear:

“—and share memories with us so that we can always be together, even when you go away to a far land. Good day.”

Four days later Tahiti rose out of the sea. Not like a string of pearls with palm tufts. As wild jagged blue mountains flung skyward, with wisps of cloud like wreaths round the peaks.

As we gradually approached, the blue mountains showed green slopes. Green upon green, the lush vegetation of the south rolled down over rust-red hills and cliffs, till it plunged down into deep ravines and valleys running out toward the sea. When the coast came near, we saw slender palms standing close packed up all the valleys and all along the coast behind a golden beach. Tahiti was built by old volcanoes. They were dead now and the coral polyps had slung their protecting reef about the island so that the sea could not erode it away.

Early one morning we headed through an opening in the reef into the harbor of Papeete. Before us lay church spires and red roofs half hidden by the foliage of giant trees and palm tops. Papeete was the capital of Tahiti, the only town in French Oceania. It was a city of pleasure, the seat of government, and the center of all traffic in the eastern Pacific.

When we came into the harbor, the population of Tahiti stood waiting, packed tight like a gaily colored living wall. News spreads like the wind in Tahiti, and the pae-pae which had come from America was something everyone wanted to see.

The Kon-Tiki was given the place of honor alongside the shore promenade, the mayor of Papeete welcomed us, and a little Polynesian girl presented us with an enormous wheel of Tahitian wild flowers on behalf of the Polynesian Society. Then young girls came forward and hung sweet-smelling white wreaths of flowers round our necks as a welcome to Tahiti, the pearl of the South Seas.

There was one particular face I was looking for in the multitude, that of my old adoptive father in Tahiti, the chief Teriieroo, head of the seventeen native chiefs on the island. He was not missing. Big and bulky, and as bright and alive as in the old days, he emerged from the crowd calling, “Terai Mateata!” and beaming all over his broad face. He had become an old man, but he was the same impressive chieftainly figure.

“You come late,” he said smiling, “but you come with good news. Your pae-pae has in truth brought blue sky (terai mateata) to Tahiti, for now we know where our fathers came from.”

There was a reception at the governor’s palace and a party at the town hall, and invitations poured in from every corner of the hospitable island.

As in former days, a great feast was given by the chief Teriieroo at his house in the Papeno Valley which I knew so well, and, as Raroia was not Tahiti, there was a new ceremony at which Tahitian names were given those who had none before.

Those were carefree days under sun and drifting clouds. We bathed in the lagoon, climbed in the mountains, and danced the hula on the grass under the palms. The days passed and became weeks. It seemed as if the weeks would become months before a ship came which could take us home to the duties that awaited us.

Then came a message from Norway saying that Lars Christensen had ordered the 4,000-tonner “Thor I” to proceed from Samoa to Tahiti to pick up the expedition and take it to America.

Early one morning the big Norwegian steamer glided into Papeete harbor, and the Kon-Tiki was towed out by a French naval craft to the side of her large compatriot, which swung out a huge iron arm and lifted her small kinsman up on to her deck. Loud blasts of the ship’s siren echoed over the palm-clad island. Brown and white people thronged the quay of Papeete and poured on board with farewell gifts and wreaths of flowers. We stood at the rail stretching out our necks like giraffes to get our chins free from the ever growing load of flowers.

“If you wish to come back to Tahiti,” Chief Teriieroo cried as the whistle sounded over the island for the last time, “you must throw a wreath out into the lagoon when the boat goes!”

The ropes were cast off, the engines roared, and the propeller whipped the water green as we slid sideways away from the quay.

Soon the red roofs disappeared behind the palms, and the palms were swallowed up in the blue of the mountains which sank like shadows into the Pacific.

Waves were breaking out on the blue sea. We could no longer reach down to them. White trade-wind clouds drifted across the blue sky. We were no longer traveling their way. We were defying Nature now. We were going back to the twentieth century which lay so far, far away.

But the six of us on deck, standing beside our nine dear balsa logs, were grateful to be all alive. And in the lagoon at Tahiti six white wreaths lay alone, washing in and out, in and out, with the wavelets on the beach.