Any day, any time, tragedy could ambush you. Women in the forces were particularly exposed. WAAFs like R/T operator Pip Beck endured helplessly as the men they loved failed to return from missions. With the Battle of the Atlantic continuing to claim lives, Wrens who got romantically involved with naval servicemen often had to confront the loss of their boyfriends. Wren Pat Bawland watched in horror as a trainee Fleet Air Arm pilot nosedived into the runway at her Somerset base. He had married one of her fellow Wrens eight weeks earlier, and the girl was pregnant: ‘I’ll never forget seeing the searchlights at night trying to dig that plane out and get to his body.’ Nobody was invulnerable. The North Africa campaign was bloody; in the Far East prisoners of war died by the thousand.

‘Hearts do break,’ remembered Bradford shop assistant Dorothy Griffiths. The staff of the branch of Marks and Spencer where she worked was fragmented by the war. Early on, one of her male colleagues had been shot down in the sea at Dunkirk. Ada, who worked with Dorothy in menswear, came from a family which seemed to have been singled out by a merciless fate. Her sister’s fiancé had been drowned in a submarine; her brother Tommy had also been lost at sea. His wife Sally was helpless, distraught: ‘[she] had only lived for the time that Tommy would come home.’ Then it was Ada’s turn: she contracted TB and died at twenty-one. Not long afterwards, Dorothy herself was at work when she received a cablegram telling her of the death of her brother Neville on board his ship in the south Atlantic. ‘I collapsed under the counter. I remember someone helping me upstairs to the rest room. I couldn’t talk … They sent me home with one of the girls. I’d no tears left.’ Later, she had to give comfort when Mollie, one of the other shop girls, got the news that she had dreaded. Her husband, who worked in bomb disposal, had been the victim of an explosion. ‘There were no survivors. We were all devastated for Mollie.’

Today, Cora Williams (née Styles) lives alone in a spotless bungalow near the Hampshire coast. Now in her late eighties, she’s still full of fight, plain-spoken and secure in her opinions. She has learned that life is a battle.

Cora Styles was only fifteen when she met her fiancé Don Johnston at a dance hall in 1938, ‘and by golly, couldn’t he dance too!’ Don joined the Royal Navy when war broke out, and in 1941 Cora left her office job at Ingersolls watch and clock factory in Clerkenwell to marry him. Her in-laws, whom she adored, were as happy as she was. ‘It was a lovely old-fashioned wedding. Don looked so handsome in his uniform. To be together was all we wanted.’ They started their married life in Londonderry, where Don’s ship was based. She was happy in ‘beautiful Ireland’, and her young husband was everything to her: ‘We were always laughing. Life was so good, you know – he was such fun. But it wasn’t to be.’

Don’s ship was on Atlantic convoys – ‘[He] was gone a couple of weeks, home a few days and then gone again.’ Then they were recalled to the navy’s main base at Chatham. Sadly, they missed seeing Don’s parents, who had sailed only two days earlier for America. ‘We tried to resume a life.’

It never, never occurred to me that anything would happen to him. Never. Well, in May ’42 Don was put on the aircraft carrier the Avenger as a stores rating. And then one night I was at my mother’s, and he rang me there and he said ‘I shan’t be seeing you for a while.’ Well of course he couldn’t say anything more precise than that. And so I said OK.

It was at this point that Cora decided to volunteer for the Wrens:

They used to say ‘Release a man for the sea.’ I thought Don would be pleased, when he eventually knew …

Well, it turned out he was back on the convoys. The Avenger sailed from Scotland and took troops down to North Africa. And having left North Africa they were off the Portuguese coast and a U-boat came up at half past three in the morning and fired a torpedo and it went amidships and hit the bomb room. And the ship blew in half, and nearly 600 men were lost. And I think actually that most of them didn’t know it happened. They must have been blown to hell.

But the first I knew of it was when I looked in the paper. They used to publish a list of ships that had gone down. And when I saw it I thought no – it can’t possibly be, they must have made a mistake. I had had no telegram, so it could not be right.

Disbelieving, Cora waited. Soon after, a cable arrived from Don’s parents, asking for news of him. She went down to the Naval Barracks Welfare section, and it was only then that she discovered what had happened:

It seems Don had never changed his next of kin when he married, so the telegram reporting him missing must have gone to his parents’ old address, and I assumed it got lost, as they were in America.

When I left the barracks, I felt stunned, I just could not believe what I had been told … It was raining stair-rods. You’ve never seen rain like it, it was literally throwing it down from the heavens. My mind seemed to have gone blank, I hardly noticed how wet I was getting. I started counting the bricks in the six-foot wall I passed, which stretched back to the High Street. The most sad thing I then had to do was cable Don’s parents: ‘Missing. Presumed killed.’

I was in a bad state. One didn’t have an understanding of what these men had gone through. They’d been blown apart. Years later I managed to get in contact with one of the survivors. He’d been on watch the night before, when they were coming out of the Med. And he saw the torpedo go past and hit the ship. And he said, ‘It was the most terrible sight I’ve ever seen in my life, and it still lives with me today.’

Widowed at eighteen, Cora Johnston (as she was now) took stock of her situation. She was waiting to hear from the Wrens, and she had no more than £49 in the bank.

I sat down and thought about things. My parents wanted me to go home and live with them and I said, ‘No, I’m going to stand on my own feet.’ So I went to the Post Office and volunteered for a Christmas job.

However, the Christmas job defeated her. Weighed down by cumbersome parcels – many of them containing bleeding gifts of furred and feathered game sent by sporting Scots to their protein-starved southern relatives – she gave in her notice, exhausted.

But the Wrens were to prove a lifeline. ‘On January 3rd they sent for me.’

Cora still had a long road to travel.

I’m someone who fights back. I’ve done it all my life. And I’m still doing it. I’m like a dog with a bone – I never ever give up.

But take it from me, you never get over it. The pain is there now, today – you never ever lose it. I still get upset. It’ll stay with me until the day I die – but whether I shall ever meet him again I don’t know.

*

Cora feels that her life has been ‘a fight from the cradle to the grave – the latter being a way off yet! I think the war turned me from a silly lovesick girl into a strong woman.’

Her experience, and that in many other accounts of lives lived through the 1940s, suggests that by its midpoint the war was starting to have a transformative effect on the women of this country. The demure, retiring, unambitious young woman of 1938 had had some hard knocks. She had felt fear, smelled death in the Blitz, dealt with body parts, seen her possessions scattered and her home destroyed. She had been bombed, bullied by regimental sergeant-majors, burned by slag and blinded by hot steel. The hierarchies that had structured her everyday existence – class, culture and sexual divisions – were all being challenged. She had new skills, new responsibilities, while at the same time learning to live without much that, materially, she had taken for granted. Meanwhile, the men she loved were far away. At any time the news might come that they were wounded, imprisoned, disfigured or dead. But she was adapting, starting to become stronger, more independent, more reliant on her innate wits and abilities.

Ask any woman who lived through that time how she coped, and the chances are she will give the same simple, stoical answer: ‘You just got on with it.’

*

A spotlight is all the brighter when the other lights are lowered. Perhaps living through those troubled, blacked-out times sharpened a sense of gratitude for moments of uncontaminated pleasure. And, too, the delight in nature and landscape; in affection and gratified desire; in food, sleep, laughter, dancing, art, a new hat or an afternoon at the pictures were in some measure enhanced by the constant reminders that love would pass and life was short. Perhaps they just had no tears left. How else to account for the curious statistic that emerged from a Blitz survey, that a fifth of women felt happy more often than before the war?

On 10 May 1942, the same day that three Royal Navy destroyers were torpedoed in the Mediterranean with over 100 lives lost, Nella Last and her husband packed a picnic of stewed prunes ‘and a tiny piece of cake’ and drove to Coniston Lake, their favourite beauty spot. After they’d eaten Nella napped in the car, then went for a stroll in the wood:

The fragrant larch boughs swung in the wind, but as I went deeper all was quiet and still, and the blue hyacinths shimmered in shafts of sunlight. Such peace, such beauty.

Doffy Brewer still remembers the rapture she felt when her work as a kine-theodolite operator took her to the deep west of Wales, where gunners were sent to train:

We were in Manorbier, which is a tiny village on the coast near the most beautiful countryside you’ve ever seen, with cliffs, and flowers. Oh, it was exquisite, it was absolutely lovely.

Our spirits used to go free, up on those cliffs. I learned to breathe, to be, to enjoy just being alive …

I used to lie down on those flowers and imagine all the plants that were there. I was enjoying myself in a way I’d never done before. I felt transformed.

And when she wasn’t kitted out for an evening’s dancing at the Institute, Doris Scorer’s days off from the Wolverton Works often meant sunny afternoons at the ‘bathings’ – a stretch of the River Ouse on the town outskirts where teenagers like her met to sunbathe, splash and flirt. It was here that Doris first met Frank White – ‘we were like soul mates’. Frank, though by origin a townie like her, knew the countryside like the back of his hand and, with Doris in her fancy shoes picking her way between the cowpats, the pair would roam the river meadows among the primroses, skimming stones and startling the water rats. Later in the year they gathered blackberries and investigated animal tracks in the snow. One evening they saw the Aurora Borealis. ‘Happy days.’

For those like Nella, Doffy or Doris who weren’t homeless, maimed or bereaved, maintaining non-stop gloom was just too much effort. The human instinct for pleasure found outlets where it could. Nella was perhaps happiest when she felt she was using her housewifely skills to greatest effect. At the end of an exhausting day unpicking a second-hand mattress, washing its cover and remodelling it into four smaller mattresses with the aid of half a dozen sugar sacks, she recorded: ‘I think I’m the tiredest and happiest woman in Barrow tonight!’ She had the capacity to find fulfilment in the small finite tasks of the home, each with its own sense of meaning, its own sense of completion. Christmas 1942 was a time of profound shortages. Being able to poach some hard-won eggs and open a hoarded tin of apricots, to be served with ‘cream’ whisked up from powdered milk and water with a little sugar, gave Nella intense satisfaction. ‘Never since the boys left home have I prepared Christmas Eve tea so happily.’ And what joy she felt, opening her presents the next day, to find two pairs of silk knickers in a parcel from her daughter-in-law Edith, and a book of stamps from her young neighbour Margaret.

Small delights grew in proportion to their scarcity. At a time when eggs were almost non-existent Mary Fedden went to the grocer and managed to get two, one of which had a double yolk. ‘We thought that was the luckiest thing that happened to us in the war.’ Barbara Pym was even luckier; she got hold of a seven-pound jar of marmalade: ‘Not even love is so passionately longed for.’ At the end of a day of black depression, missing her prisoner-of-war son, engulfed with uncertainty about the future, Clara Milburn found that going to church lifted her spirits. And later she went out into the garden, rejoiced quietly at the fading colours, took true pleasure in her new permanent wave and felt blessed by the regeneration of a damaged thumbnail that had finally ceased to be unsightly. What luck, too, to possess a wickerwork wheelbarrow, a sweet dog like Twink, friends and a home.

Hard work brought unexpected rewards. Susan Woolfit’s war work as a member of the all-female crew of a narrow-boat plying the inland waterways of Britain gave her life new meaning; petty irritations melted away in the face of an engrossing and physically demanding activity. Housework, queues, rations, responsibilities, keeping up appearances and the sheer ennui of war were replaced by thrilling excitement: ‘I was enjoying every second of it.’ She loved the boats themselves, their cosy cabins shared with congenial companions; she loved the still black nights on the canals, and the early mornings as the boats started up again, with the locks clanging and the water surging. Her work left her ‘revitalised and vibrating with life and new hope’.

‘You lived at that period from day to day,’ says Cora Johnston. ‘You had to because you would have gone under if you hadn’t. Today was IT – because you never knew if the next day was going to be your last.’ In some ways war made life less complicated. ‘Why hesitate? Why defer?’ was the insistent message that drummed through every disaster, every blow dealt by fate: ‘Do it today. Do it now. Work – travel – experiment – enjoy – dance – love – live.’

Phyllis Noble longed for adventure. But, aged twenty-one, she felt trapped in a backwater. She had never in her life travelled more than 50 miles beyond London. Now, three and a half years after the declaration of war, she was still living under her parents’ roof in Lewisham, still a wage-slave, still enduring the daily ordeal of travelling through bombed streets to her ‘reserved occupation’ in the foreign accounts section of the National Provincial Bank. ‘That wretched bank. I’m so fed up with the endless routine work I could scream and scream every time I sit down at that hateful machine … It is high time I started making up my mind what I really want in life,’ she confided to her diary, listing love, travel, a minimum of two babies and educational improvement (‘there is so much I want to learn’) as essential must-dos for the future.

Phyllis had had a grammar-school education and in autumn 1941 had enrolled with her friend Pluckie for evening classes at Morley College. She was naturally inquisitive and intellectual, and the classes had awakened in her radical ideas: socialism, internationalism, feminism. They also stimulated her thirst for travel and independence, and yet, beyond the nine-to-five treadmill, the future seemed only to offer a reprise of her mother’s experience: housework, motherhood and drudgery.

This destiny seemed all the more preordained after she started going out with a friend of her brother, Andrew Cooper. Andrew had much to recommend him as a boyfriend. He was good-looking – blue-eyed with a silky mop of dark hair – besides being musical and a talented artist, and romance bloomed. Phyllis’s parents approved of him too: they could see that his culture made him attractive to their daughter and, more importantly, he was safely and respectably employed. As a draughtsman with an engineering firm designing war weapons, Andrew was in a reserved occupation. The Nobles made him welcome for cocoa when he dropped in on his way back from Home Guard duty, or for tea on Sundays.

But despite, or because of, the settled nature of her relationship with Andrew, Phyllis now started to play a game of emotional roulette. How had she found herself living in a boring suburb, rooted in a boring job and all but engaged to her steady boyfriend, when around her the world was on fire? ‘The dramatic events [of the war] served to increase my discontent with the dull part I was playing in them.’ She knew she was flighty, bad and irresponsible but, like a gambler let loose in a casino, she couldn’t stop herself: ‘I was often uneasy about my capricious behaviour but unable to control it.’

It started with James, an intellectual Yorkshireman who worked at the bank. His good looks and dubious reputation both as a pacifist and a womaniser only enhanced his attraction. Pluckie too was besotted. With his misty eyes and searing intelligence he had both girls at his feet. Phyllis made a date with him to go second-hand book-shopping; the cover story failed to convince Andrew, who was openly jealous. But on this occasion her transgression went no further than an intense conversation in his Bloomsbury garret: ‘I hugged my knees in delight at what still seemed to me this daringly unconventional act of being alone with a man in his bed-sitting room.’ But that was all. Nevertheless, her susceptibility to stray bohemians continued to get the better of her.

Next was Don, an artist manqué who had worked at the bank: Phyllis and he had had a brief dalliance back in 1940, after which he had been called up by the RAF and sent for pilot training in Canada. Now, newly debonair and dashing, he reappeared on leave with the coveted wings gleaming on his breast pocket. When he also happened to mention that he had returned from Canada with no fewer than eighteen pairs of silk stockings in his suitcase, Phyllis was bowled over, but had to explain, very reluctantly, that she was about to leave for a week’s holiday in Wales with Andrew. She promised to telephone Don as soon as she got back, fearing that in her absence he would find another taker for the silk stockings. Meanwhile, she and Andrew holidayed chastely with his grandparents in their seafront cottage, and war seemed far away as they trekked the craggy hillsides of Snowdonia and picnicked beside glittering waterfalls. ‘By the end of the week in such surroundings I was almost certain that Andrew was to be my one true love.’

Almost certain. Back in London, she was straight on the phone to Don. Don had given half the stockings to an ex-girlfriend, but spared no expense to wine her, dine her and take her out to theatres. They both knew that life was short in Bomber Command, and neither had any qualms about dropping their commitments to enjoy a heady whirl of pleasures. Youth would pass, the music would die, kisses were there to be snatched. It was all over in a fortnight – but the remaining stockings were hers.

Andrew, however, stayed loyal. By now he was ‘almost a member of the family’. He was virtually regarded by her parents as their future son-in-law, and it became more and more difficult for Phyllis to detach from him. Yet the inevitable culmination of the relationship – marriage – was abhorrent to her. Five years earlier, in the pre-war world, Phyllis’s dilemma might not have been so acute. As with so many young women, the war had thrown opportunities at her that, in 1939, would have seemed out of reach. The uncertainty of war was contagious. What law said that you had to marry a boyfriend because your parents liked him? Who had ordained that one couldn’t have a bit of fun, play around, travel, experiment? The forces of convention grabbed her and held her captive; breathless, she thrashed and writhed for a little liberty, a little space:

I would not give up my freedom to go out with other men friends, such as Don, which must have caused Andrew as much misery as my recurrent attacks of discontent and despondency.

… I suddenly decided to break off from him. In a way, I still believed I loved him, yet I knew I did not want to marry him and nor did I want to go on as before.

Within a few weeks, circumstances were to drive her back. She discovered by chance that Andrew had fallen ill; he was in hospital with suspected tuberculosis. Filled with remorse, she dashed to his bedside, and as soon as he recovered they were lovingly reunited. This time Phyllis dropped any inhibitions she may have clung to. She had long ago rejected the idea that virginity should be preserved until marriage; her future, she was convinced, held brighter dreams than just being a wife. And so the irrevocable step was taken one Sunday afternoon on the floor of his parents’ sitting room while they were out. It was not a romantic setting: the pink and beige patterned carpet on which they embraced was curiously at odds with the brutal form of the iron Morrison shelter that dominated one side of the room. But she had no regrets. On the contrary, it was a coming-of-age, an awakening to the happy discovery of her own passionate nature.

March 8th 1942.

A new page for a new era – At last I’ve gone over the precipice!’

It is certainly true that for many women the war years were dominated by exhaustion, worry, shortages, fear and broken hearts. But the hopelessness and unhappiness of war tend to eclipse the sunny intervals. Phyllis Noble’s newfound physical infatuation with Andrew was of this kind: a series of tender, radiant vignettes that sit brightly beside the familiar monochrome home-front snapshots of food queues and factory lines. Desire had taken hold of them both. Now, whenever they could be together, they looked for privacy, a place to drain and exhaust their urgent appetites. After dusk, parks were good places; since the Blitz, the wrought-iron gates were no longer closed, and they would find a bench there under the majestic elm trees. At weekends the woods, with their undisturbed forests of deep bracken, were a bus ride away. Phyllis’s cousin Nel, who took a warmly broad-minded attitude towards the young lovers, invited them to stay in her primitive cottage in Hertfordshire. There were enchanted nights with the owl hooting outside the bedroom window, candlelight illuminating their amorous exertions as they struggled to tear their clothes off and climb under the eiderdown. And a holiday in the West Country – despite the landlady who conformed to type by firmly allocating them separate bedrooms – offered the magical seclusion of empty moorland and sheltered hedgerows. They took bus rides to the coast and explored the cliff walks. In Dorset it was possible to buy cream cakes; they sat on the Cobb at Lyme Regis and devoured them, looking out to sea. At their lodgings they dined on hearty home-cooked fare, and ration books seemed to belong to a world they had left behind. Before bed they wandered again hand in hand between the high, violet-scented banks, and watched a spring moon rise over the darkening hedgerows.

*

Joan Wyndham’s war was more crème de menthe and amphetamines than moorland hikes and cream teas. She was only nineteen when she qualified as a WAAF filter room plotter, too young and dizzy to have felt the pressure of home responsibilities. But war not only sharpened her appetite for excitement, drink, friends, men and fun, for a convent-educated virgin it offered unimaginable liberty to indulge them. And once she’d been relieved of her onerous chastity and acquired some contraceptive Volpar gels she launched into a free-spirited round of amorous adventures. In September 1942 Joan was posted to Inverness. That meant parting from Zoltan, her Hungarian lover in London, but she had few regrets, and shortly after arriving at the WAAF mess she had the complete low-down on all the available males within a 10-mile radius. There was Bomber Command HQ, and the Cameron Highlanders were the local regiment. Canadians were based in the area, and battleships arrived frequently. Even better, the Norwegian navy was much in evidence: ‘they’re gorgeous, sexy and very, very funny … they drink like fishes and take over the whole town’. But the hottest attraction, married though he was, was Lord Lovat,* who trained his commandos in the grounds of nearby Beaufort Castle: ‘There is not a girl in our Mess who doesn’t secretly lust after him – including me!’ Great excitement, therefore, when the WAAFs got an invitation from the Royal Engineers to a dance at their mess, which was based at the castle. Unfortunately, his Lordship wasn’t there. However, Joan danced with the next best, Lord Lovat’s cousin Hamish. ‘We got drunk together and I was on top form and happy as hell.’

For Joan, time off duty now meant dates at the castle to join Hamish in his aristocratic Highland activities. She accompanied him in borrowed brogues for shooting expeditions, admiring his ‘jutting, compact Highland bottom’ as he slaughtered the local wildlife and waited for him to make a pass at her. Up hill, down dale and through swamps they stalked deer and capercailzie, tummy-down in the heather: not Joan’s idea of a good time until, flat on their faces in a bog one day, Hamish gasped, ‘God, I want to rush madly to bed with you!’ Hamish now offered a couple of days of bright lights in the big city, so Joan applied for ‘forty-eight’ and travelled to London at the earliest opportunity. With Hamish in his best Savile Row suit and Joan in her favourite little black dress, they hit the Bagatelle for cocktails – ‘Three martinis later we were both floating’ – followed by the Gargoyle for smoochy dancing, and then on to the 400 Club, with bowing waiters proffering brandy. As for sex, nothing was settled until they were in the taxi lurching back to Chelsea, whereupon he kissed her and popped the inevitable question: bed? Joan promptly caved in: ‘I seem to find it awfully difficult to say no to a member of the aristocracy.’ It had something to do with blue blood, she confessed. Sadly, the seduction scene was a disappointment: ‘He was enormously heavy, and it was rather boring and seemed to go on for hours.’ A streak of maudlin Catholicism inhibited poor Hamish from climaxing, and – explaining that he had to get to early Mass the next morning before catching his train – he declined to stay the night.

Onwards and upwards: in January 1943 Joan got news that gorgeous German Gerhardt, her first love, had returned from internment in Australia. They engineered a reunion in London, but this time Gerhardt seemed somehow ‘old and rather grubby’. She rejected his offer of bed, but friendship was restored over a Soho pub crawl, ending at the Café Royal. Being a WAAF didn’t mean putting all the old bohemian days behind her. Back in Inverness she surpassed herself at the St Valentine’s dance with a combination of gin, rum, Algerian wine and Benzedrine. And life in the north of Scotland started to look up greatly with the arrival for refitting of the Norwegian ships, complete with mad, sexy, blue-eyed, blond Viking crew and limitless supplies of Aquavit. Joan fell for the first one to pick her up, Hans, who was six feet tall with ‘the face of an angel’. At the May Day party he also proved to be ‘a wizard dancer’:

Dancing is the thing I like best in life … I danced with a narcissus between my teeth, and I can remember thinking – in the middle of a rumba – that I was so happy that I wanted to cry.

By 8 May she was writing in her diary:

Life is a dream of spring and fine weather, moonlit nights and beautiful young men …

and on the 18th:

I definitely love him.

Finding somewhere to go to bed together was a puzzle, until Joan got hold of WAAF insider information about a little hotel by Loch Ness, ‘where everybody goes for their dirty weekends’. Hans proved sweet, handsome and somewhat inexperienced. They spent a wakeful night of passion; for him, at least, since Joan persisted in finding that the proceedings left her cold, physically if not emotionally. ‘I felt nothing, except for love.’

Nevertheless it soon turned out that compatibility, sexual or otherwise, had nothing to do with it. Hans disapproved of Joan’s habit of writing poetry; he also hated ‘pansies’, painters, and ‘creeps who wear berets’. His idea of a nice normal woman was a cross between a blonde Vikingess ready to hike mountains and sail fjords and his mother, with a hearty meal of reindeer meat and cloudberry jam all ready for her son when he got in from skiing. This led Joan to wonder what could possibly be the attraction of such an uncultured outdoorsy Philistine:

Maybe this love of ours is just some kind of sick aberration only made possible by the war?

Maybe. Early in July Hans and the refurbished ships sailed for the Shetlands; Joan was posted to East Anglia for a refresher course, followed by a few free days in London: time for a riotous binge in the company of notorious beret-wearing bohemians Julian MacLaren Ross, Nina Hamnett, Tambimuttu, Ruthven Todd and Dylan Thomas. But the revels ended prematurely when the air-raid siren went off. The company piled into a taxi, with Joan squashed up against a lust-crazed Dylan; back at Ruthven’s studio Joan was offered a mattress and a cupboard-sized room, where she took the precaution of wedging a chair under the door handle and tried to sleep as the bombs crashed outside. Impossible. Dylan was rattling at the makeshift lock, with cries of ‘I want to fuck you! I want to fuck you!’

‘I had a simply wonderful leave – my heart was broken four times.’ Away from watchful parental eyes, many young women revelled in the opportunity for off-duty romance.

There were ominous thuds as Dylan hurled himself against the panelling. Thump went Dylan! Crump went the bombs! …

At last I heard Ruthven’s voice firmly remonstrating, and finally the sounds of a heavy body being dragged reluctantly away.

I curled myself up under my greatcoat and slept like the dead.

*

Elizabeth Jane Howard was another hugely talented writer who confesses that her war was largely defined by men and sex. ‘I do think people went to bed with each other much more easily,’ she says today, ‘very largely because it might be the last thing they did. It’s probably Nature’s way of preserving the human race.’ Old age has given Jane Howard a kind of queenly assurance, as well as an unembarrassed honesty about her own youthful faults. In her autobiography Slipstream (2002) Jane Howard describes herself as ‘essentially immature … I’d succeeded in nothing …’ She tells how she was turned down by the Wrens (who considered her under-qualified), and describes her unhappy marriage with Peter Scott. But in 1942 Jane became pregnant. As an important naval officer, Scott was allowed to have his wife billeted in a comfortable hotel close to his base, but he was out all day. ‘I was homesick, and I didn’t know what the hell to do with myself.’ Pregnancy exempted her from war work. ‘I read, I ran out of books, and I went for walks … I felt terribly sick. And the only thing to eat at this ghastly hotel was lobster. You try having lobster twice a day for three months when you’re feeling rather queasy.’ That winter she moved back to London. On 2 February 1943 – the day the Germans surrendered at Stalingrad – her daughter was prematurely born during an air raid.

But after a traumatic birth, Jane lacked maternal feelings for baby Nicola, who screamed, wouldn’t feed and only compounded her sense of inadequacy. That summer she fell in love with Wayland Scott, her husband’s brother. ‘The first time he kissed me I discovered what physical desire meant … I was his first love as in a sense he was mine.’ They cemented the guilt by sleeping together, then owning up to Peter. There was a terrible row, and Jane was carted off to stagnate at his naval base in Holyhead. But it was only a matter of time before the vacuum in her life was refilled. Threatened by boredom in Holyhead, she decided to put on a production of The Importance of Being Earnest with the navy, with Philip Lee, a handsome blond officer, playing Algernon to her Gwendoline. One winter afternoon they climbed Holyhead Mountain and made love among the crags. The affair continued after her return to London, where they borrowed a painter friend’s studio for delicious, secret assignations. ‘I don’t think Pete ever knew about it.’

*

Meanwhile, Phyllis Noble still felt uncommitted, despite the physical bond that now held her to her lover. Her insistent sexual desire for Andrew seemed to point in the direction of commitment. Her parents liked him; her choice of boyfriend, if not her illicit sex life, had their blessing. But the war pushed in the opposite direction. Nursing, perhaps, would give her the chance to ‘do her bit’ while experiencing foreign parts. But in late 1942 the government was drawing ever more women into the conscription net, and, finally, Phyllis heard that she was to be released from the bank. However, conscription took little account of preferences; you had to go where you were needed, and the fear that she might be called up for the dreaded ATS made Phyllis consider, briefly, whether it would be best to avoid the whole thing by just going ahead and getting married. ‘I knew Andrew was willing, and sometimes during our best moments together I thought I might be too. Then I would draw back – for, to me, marriage continued to seem like the end of the road.’ And as the trap she most feared seemed to close on her, Phyllis blundered into yet another reckless relationship.

A good-looking redhead, with confidence bordering on arrogance, Stephen was another young man who had paid court to her at the bank, before disappearing – like Don – for overseas RAF training. That autumn he returned and quickly homed in on Phyllis. His glamour, domineering manner and well-travelled sophistication rendered her helpless, and she soon persuaded herself that it would be unkind not to ‘help him enjoy his leave’. This didn’t mean sleeping with him: ‘Stephen was willing to accept that our relationship must for the time being remain platonic … Andrew remained my lover but had to put up with my temporary desertion each time Stephen appeared on leave.’ Then in March 1943 Phyllis was accepted by the WAAF. She put herself down to train as a meteorological observer. Soon after, Stephen proposed to her and, swept off her feet, she accepted. That night she agonised about what she had done. This was a man she barely knew, had hardly kissed, felt no physical attraction for, and yet she could be pregnant by Andrew. Her family reacted with predictable horror, but Phyllis, now wearing a diamond and garnet cluster on her finger, was too deep in to backtrack. Circumstances came to her rescue, but the cost was high. Stephen’s aircraft crashed. He survived, severely burned, after being pulled from the wreckage. When she visited him in hospital, he honourably suggested releasing her from the engagement, which initially she felt unable to agree to. ‘But … whatever had drawn us together was waning.’ They parted, and she returned the pretty ring, feeling she had learned a damaging lesson. Lovers were one thing, a husband was quite another.

*

Times were changing. For women in wartime, the wages of sin were often automatic dismissal, but no longer always automatic disgrace. Meanwhile, male attitudes remained predictably primitive. In time-honoured fashion, men continued to achieve a mental disconnect between their sexual and emotional needs. The pin-ups of bosomy Hollywood starlets and scantily clad cutie-pies adorning army accommodation and Spitfire fuselages played into a fantasy driven by lust and loneliness. So did ‘Jane’,* the Daily Mirror’s famous curvaceous cartoon blonde, credited with boosting troop morale every time her skirt got caught in a door or she lost her towel on the way to the shower. And if centre-fold girls didn’t do enough to quench a man’s libido, there were plenty of real-life vamps out there ready and waiting to do their bit. Servicemen away from home could take a ‘pick’n’mix’ approach to the locals, the amateur fun-lovers and the so-called ‘good-time girls’. If you were in a hurry, or in transit, you consulted the graffiti on the toilet walls at barracks: ‘Try Betty, she’s easy’ and so on. Ex-WAAF Joan Tagg remembers that when she was stationed at Oxford ‘there was a girl there called the camp bicycle. I didn’t know who she was, but all the boys there who needed her would have known.’

‘Jane’, with only a union flag to preserve her modesty.

Where there are soldiers there are camp-followers. Wherever it might be, at home or abroad, the army attracted another, shadier army of women cashing in on a captive market and (in Britain) a law which turned a blind eye to the activities of street-walkers. The blackout favoured their dubious trade; in London they were dubbed the ‘Piccadilly Commandos’. The numbers of such women reflected the increase in conscripts and, to the dismay of the health authorities, venereal infections showed a parallel proliferation. In the first two years of the war new cases of syphilis in men were up 113 per cent, in women 63 per cent. With the arrival of the GIs such diseases reached almost epidemic proportions. Outside Rainbow Corner – the American servicemen’s club on the corner of Shaftesbury Avenue – the ‘Commandos’ were like bees round a honeypot; one US staff sergeant recalled how they swarmed round the darkened West End:

The girls were there – everywhere. They walked along Shaftesbury Avenue and past Rainbow Corner, pausing only when there was no policeman watching … At the underground entrance they were thickest, and as the evening grew dark, they shone torches on their ankles as they walked and bumped into the soldiers murmuring, ‘Hello Yank’, ‘Hello Soldier’, ‘Hello Dearie!’

Apparently they often issued a supercharge of $5 – ‘to pay for blackout curtains’. Sex was on the streets as never before. Less recognised is that some of these prostitutes were themselves servicewomen. Flo Mahony was a WAAF who shared her accommodation at her Swanage base with a pretty young woman named Phyllis, who regarded the nearby men’s camp as a business opportunity:

She was a WAAF driver – a great friend of mine, and she had been a prostitute … Well, she would get dressed up and go off out at night. We covered for each other – and obviously we all guessed. She had red cami-knickers, she’d always got perfume and she’d always got talcum powder – things which were quite difficult for us to get. We never talked to her about it, but she went with servicemen I suppose. We all liked her, and she was no trouble to us.

The army was also a two-way traffic for sex workers: the services might offer an escape route to women trapped in a degraded profession – ‘I’ve been working in London for years as a prostitute,’ one of them confided to a fellow recruit, ‘and I joined up to try to leave it all behind me.’

Meanwhile, four years of war had not shifted men’s deeply rooted presumptions as to what they felt owed by women. On the one hand, they wanted to go to bed with them. And men could be selfishly persuasive if they wanted sex with married women: ‘A slice off a cut loaf ain’t missed.’ On the other hand, they wanted to be mummied, fed and looked after. They expected fidelity, modesty, domesticity and duty. Scattered over battle fronts from Mandalay to Mersa Matruh, husbands and boyfriends now nurtured the dream of coming home to find their domestic goddess fantasy intact. But things were changing. Disturbing clashes often resulted:

‘How can I be sure she will be true?’

‘Every time my husband comes home on leave I am terribly thrilled. But when we meet it is nothing but silly little squabbles.’

‘My wife is working on a farm and I am in the Army … Each time I come home I see her being very friendly with the farm men. I feel angry and suspicious.’

‘He asked me to clean his army boots for him.’

In 1939 there had been just under 10,000 divorce petitions. Now, not surprisingly, divorce rates surged. Women – and men – often embarked hastily and ignorantly on marriages which they then repented. But the millions of wives working in factories and army camps didn’t have time to keep the home fires burning. The domestic goddess had hung up her apron and donned overalls or battle-dress. She was out earning good money and she was placing her duty to her country above her duty to her home. By 1945 that figure had increased to 27,000 petitions, 70 per cent of these on grounds of adultery. Had it not been for the conviction among many respectably brought-up girls that ‘hanky-panky’ was wrong there would surely have been many more.

But if innocence, trust and tradition got misplaced along the way, well, there were compensations. Making love in the crags or amid the bracken, dancing the rumba, spring nights and beautiful young men all helped to banish the miseries of war – and who would blame anyone for trying to do that?

*

Jane Howard’s baby daughter Nicola had made an inauspicious start to life in 1943. Jane had endured a wearisome pregnancy and gave birth three weeks early after a long and agonising labour. In the following weeks she tried and failed to love the screaming little scrap who had cost her such pain and fatigue. ‘I’d not wanted her enough and was no good as a mother.’ She put her love affairs before her child at this time, and many years were to pass before her maternal feelings eventually matured.

Babies, however, were very much wanted by the powers that be. Before the war, there had been much wringing of hands over the decline of the birth rate in Britain. By 1939 it had dropped to below replacement levels, with 2 million fewer under-fourteens than in 1914, and a worsening situation developing by 1941. With worries about a shrinking and ageing population the correspondence columns of the press were deluged with anxious letters, of which the following are typical:

14 March 1942

Let us see a state-sponsored plan for the systematic increase of our population before it is too late.

9 October 1942

What are we doing about our … birth-rate, the increase of which must be considerably curtailed by the fact that innumerable husbands serving in the forces have been sent overseas for the duration of the war?

One explanation given for the statistics was that parents were too filled with gloom about the future to go forth and multiply. Mass Observation interviewed a young woman – a midwife – who angrily accused the authorities of trying to persuade women to breed more soldiers as cannon fodder: ‘I think it’s horrible. They don’t want the babies for their own sakes at all, just for wars.’ However, the 1943 figures, when they were published, showed an unexpected turnaround. Nicola was one of 811,000 babies born in the UK that year, a rise of 115,000 from 1941 figures. After that, the figures continued to increase. The analysts breathed a sigh of relief. It seemed that the practice and profession of motherhood would not go into irreversible decline and that we would not, after all, be overtaken by the fecund Germans. (When Naomi Mitchison’s daughter-in-law told her she was expecting a baby at this time, Naomi’s reaction was: ‘It’s one in the eye for Hitler.’) An explanation for much of this boost was that large numbers of young people born in the last, post-First World War baby boom were now reaching maturity. There was also the fact that 1939–40 had been a peak year for marriages. However, included in that 1943 figure of 811,000 births were 53,000 babies who were illegitimate – a figure also set to rise as the war progressed.

Behind the statistics lies a multitude of sad case histories. On 23 March 1943 Nella Last confided to her diary the upsetting tale she had been told that day by a complete stranger at the WVS centre. This woman had burst into tears without warning; Nella fetched her a glass of water and listened while she unburdened herself: ‘I feel I’m going out of my mind with worry.’ Her twenty-three-year-old daughter, it appeared, was a married Wren, whose husband had been a prisoner of war since Dunkirk. However the girl had no intention, it seemed, of repining; she was always the life and soul of every party, and it now transpired that she was five months pregnant. Between sobs, the mother told Nella that she and her husband were being torn apart by their daughter’s predicament; the father, in a great rage, accusing her of being a slut, with the mother inclining to believe her daughter’s tale: that she knew nothing of how this had happened and must have been ‘tight’ at the time. Nella sat with her and did her best to soothe her, but the poor woman was distraught.

Unmarried servicewomen who fell pregnant were duly noted on a POR, or Personal Occurrence Report, then issued with ‘Paragraph 11s’ and dismissed from the force. In the WAAFs, for example, ‘it was a fate worse than death to get pregnant – you were out!’ One ATS officer posted to the Orkneys commented on the extreme number of ‘Para 11s’ issued in her company – inevitable, she suggested, given that there were no fewer than 10,000 men on the island in two ack-ack brigades. However it could be hard to tell if the girls were pregnant, as the ATS uniforms were oddly bulky and could hide a multitude of sins. One girl was heard screaming in her hut; she was packed off to hospital with a case of ‘severe constipation’, where it turned out that she was giving birth.

Far worse was the nightmare ordeal suffered by QA Lorna Bradey, who in 1942 was based in a Cairo hospital. While there she got a surprise message from an old nursing friend who had come down on leave from her hospital in Eritrea. ‘Could I come at once to her hotel … urgent.’ Lorna went down as soon as she was off duty and found her friend lying on the hotel bed, bleeding copiously. She had become pregnant by a very ‘high-up’ official and had travelled to Cairo for a backstreet abortion. To Lorna, who had studied midwifery, it was immediately plain that her friend could die at any moment and must be got to hospital. The friend begged her not to betray her secret, leaving Lorna no choice. She massaged her uterus, packed her out with towels, and obtained black-market antibiotics. ‘Sepsis was the thing I feared most. I made her swallow a good handful of these.’ Throughout the night Lorna sat with her, taking her weakening pulse, mopping up as coagulating blood and fragments of placenta came away from the welter of redness between her legs. At long last the antibiotics took hold, and the bleeding slowed. Lorna, having saved her friend’s life, visited her over the next week as she improved, after which she returned to her unit – ‘weak but alive’ – and well enough to spin a tale about ‘gippy tummy’. Despite Lorna’s stupendous efforts, this friend broke off contact with her after the war. She knew too much.

Barbara Cartland stressed, however, that pregnant servicewomen like this were in a tiny minority. In her view, it was only surprising that there weren’t more illegitimacies in the services, considering the danger and proximity that men and women underwent together.

Civilian women were often fair game for the soldiers. Seventeen-year-old Vivian Fisher’s husband first deserted from the army and then walked out on her. Left on her own, Vivian took consolation in the arms of a soldier serving with the Royal Engineers; she had a baby girl by him, but he too beat a retreat. ‘I was devastated … it took me a time to get over the hurt.’ Her next baby, a boy, was born to Jimmy, an attractive GI who promised to marry her and take her back with him to America. She would have gone had her errant husband not returned unexpectedly. Another woman whose husband was abroad slept with a GI and got pregnant but decided her lover must not know, otherwise he would never let her go. Heartbroken, she finished with him, while suffering torments at the thought that she was also deceiving her absent husband.

Distance could cause terrible misunderstandings. A soldier based in Iraq went to his brigadier in great distress, having received the following cable from his wife: SON BORN BOTH DOING WELL LOVE MARY. He hadn’t seen her for two years. The brigadier did his best to comfort the poor man, who departed – only to return shortly afterwards waving a letter which explained everything to his entire satisfaction. ‘It’s all right, sir, it’s not her it’s my mother. She’s a widow. Must have been playing around with some man.’

The agony aunts did their best to respond to desperate women like this one who wrote in about their infidelities:

My husband is a prisoner of war, and I was dreadfully depressed and lonely until I met two allied officers who were very sweet to me. Now I realise that I am going to have a baby, and I don’t know which is the father.

Do anything to avoid hurting your husband, advised Woman’s Own.

Motherhood in wartime carried its own particular burdens. Pregnant mums (dubbed Woolton’s ‘preggies’ from the minister’s concern to distribute rations among the ‘priority classes’) didn’t get extra clothing coupons. They were expected to let out their existing dresses to fit, though with their green ration books they were first in line for extra milk, meat, eggs and orange juice concentrate. Bombs were blamed for miscarriages; babies might be born in air-raid shelters or under tables in the blackout; traumatised and exhausted, their mothers often found their milk supply dried up.

If you took the decision to evacuate your children for their safety there was the pain of separation. But Madeleine Henrey and her husband decided to stick it out in London for the duration. Little Bobby, born in summer 1939, grew up to the sound of exploding bombs, and his loving parents, who had already had to take the dreadful decision to leave Madeleine’s French mother behind in German-occupied Normandy, were reluctant to split up their family more than they had to. The Henreys had taken a small flat in the Shepherd Market area of Mayfair; it was modern and solidly built. With a very young baby, Madeleine was not expected to take on war work; she spent her days wheeling the perambulator down the shrapnel-strewn pathways of Green Park, with Pouffy the Pekinese snuggled into Bobby’s coverlet. She got reproachful looks from some of the local Londoners who thought her misguided for keeping the child in the city, ‘but he grew plump and rosy-cheeked, oblivious of the thuds that woke us from time to time’. After a while the market costers and other shoppers got to know Bobby as ‘the child who would not be evacuated’ and treated him as a kind of mascot. When Robert Henrey returned from his office at the end of the day, he was often greeted by strangers giving him cheerful updates on his small son’s progress.

Verily Bruce was another young mother who had no misgivings about her role in the war. In August 1940, when she married Donald and became Mrs Anderson, she reflected that she had now found her ‘real aim in life’. She continued to harbour writing ambitions, but despite Donald’s ministry post she was mostly kept too busy to fulfil them. Pregnant during the Blitz with the first of her five babies, she took up knitting ‘tiny garments’ and found the work so soothing that she was able to ignore the bombs. In spring 1941 Verily was awaiting the birth in a maternity home in Esher, in the next bed to Julie, a lively and loveable Cockney evacuee. Verily had Marian ten days after Julie’s little boy James was born. The mum network quickly proved valuable for them both. Julie was lodging with a horrible landlady who made her wash the baby’s nappies in a bucket in the yard; she was miserable. The Andersons had a spare room. Why shouldn’t Julie and her baby move in with them?

‘Oh, wouldn’t it be lovely!’ she said. And then she came back and said, ‘I’m afraid I can’t do it …’ And I said, ‘Oh, but it’s all arranged, our babies are going to be brother and sister …’ At which point she burst into tears and said, ‘You see I’m not married.’ ‘Good heavens,’ I said, ‘that’s nothing! All the more reason why you should come.’ So she did, and she was absolutely wonderful, because I was very ill after the birth, and she just took over both babies until I was better and could help. And she could do the housework very much better than me!

By the time air raids on London resumed Verily had two small children. Three-year-old Marian found that the bombing provided a thrilling distraction from bed-time. As newborn Rachel slept beatifically in her cot she would bounce excitedly on her parents’ bed listening to the bombs whistling over St John’s Wood:

‘One two three and a –’

‘Bang!’ she shouted with delight as the bomb exploded.

‘More bangs?’ she asked hopefully.

‘Oh, the woos,’ she said regretfully of the all-clear, knowing it meant she must return to bed.

Soon after, Verily and her two small daughters evacuated to Gloucestershire and set up home with a couple of friends who were there, working as land girls. Their husbands were abroad, and one of them had a young baby. Cockney Julie and little James joined them, and Donald came when he could. While her friends were out milking cows and lifting turnips, Verily took lodgers, did the cooking, looked after the dogs and ran a kind of women’s baby co-operative for all four children.

Verily Anderson’s memoir of her wartime experiences sits oddly beside the piles of books written by so many of her female contemporaries, with titles like We All Wore Blue, A WAAF in Bomber Command or The Girls Behind the Guns. The servicewomen write about uniforms and drill, camps and operations, romances and mess dances. In Spam Tomorrow, Verily – and she was typical of many thousands – writes about maternity wards and sick infants, orange juice and sweets, about threadworm, tonsillitis, cod-liver oil and the balloon and cracker shortage, and about how the only way to obtain a nursery fireguard was to salvage one from a bomb site. Babies had become her life. Even when a well-meaning friend persuaded her to take an evening out and go dancing at the Bagatelle she found she had lost the appetite for adult dissipations. Reluctantly she put on her best dress, donned false eyelashes and accepted a glass of champagne. It was no good. Her favourite club just seemed tatty, and the clientèle looked shallow and laughable capering around the room. ‘We were … too sapped by the war and work and babies to do more than sit and wilt until the time was decent to go home.’

War and work and babies. Verily had a Cockney mother’s help and a husband at home, but she still felt drained and exhausted.

War and men, war and sex, war and relationships. Negotiating a personal life while holding up a gruelling job proved formidable enough – all the more so for the many whose war work took them far from home, at times into the field of battle. In 1942–3 QA Lorna Bradey’s career was to bring her up against some of the toughest challenges she had yet faced. She, and many women like her, endured the worst that battle zones could throw at her, proving the equal of men in stamina and courage.

Lorna’s story, told thirty years after the war had ended, is not exceptional. Her experiences were typical ones for the indomitable nurses who staffed army hospitals in combat zones wherever they were needed, but they offer a vivid case history of the everyday stress, danger and brutally hard work that women like her encountered on active service abroad. At the same time, Lorna’s account reminds us of the rapture, the thrills and the intensity bordering on hysteria that often accompanied the pressures. For Sister Bradey, those were days never to be forgotten.

Almost a year after Alamein, and with the Americans now firmly entrenched in the war, our enemies were beginning to take the defensive position. Early in July 1943 160,000 Allied soldiers landed in Sicily, taking the Italian and German divisions by surprise. From a British perspective, it was too early for a Second Front, and victory on the Italian mainland would re-establish Mediterranean dominance.

By November 1943 Lorna had already been working abroad for two and a half years with no break to return home. Now, as the 8th Army prepared to battle its way up the Italian peninsula, she and eighty of her fellow QAs were shipped from Tripoli in Libya to ‘an unknown destination’. It wasn’t hard to guess where: ‘Sure enough we were dumped at Taranto.’ From there they were taken to the small port of Barletta, further up the Adriatic coast from Bari.

‘I would travel, see everything and have plenty of fun’ had been Lorna’s stated ambition since the start of the war. But the Italian seaside in November was not alluring: it was grey, rain-whipped, mosquito-infested and muddy. The girls’ accommodation, in the form of Nissen huts, had yet to be built, so they were lodged in the unheated town museum, provided with only two primitive toilets for all of them: ‘a nightmare’. A dreadful episode ensued when these toilets became totally blocked, and excreta overflowed down the museum stairs. The hygiene officer was summoned and ordered an eight-seater communal latrine to be constructed in the museum courtyard, with buckets. In the course of her duty Lorna saw suppurating wounds, amputations, burned-away faces, yet of all the experiences she underwent this was among the most traumatic. ‘I never quite got over that – one’s most private function in public. Women have other private functions to attend to monthly and the agony was awful.’

Nevertheless, the girls set out to enjoy themselves. The hospitable local bar-owners, Alvise and his wife Lilli, had access to black-market cheese, coffee and wines; Lorna and a group of nurses were invited back for mountainous bowls of spaghetti and tomato sauce, followed by a succulent roast, and torta, washed down with the local Spumante. Somehow they overcame the language problem and ended up dancing for hours. ‘What fun we had.’

At the Barletta base hospital, casualties were coming in from the Allied advance, which that winter was grindingly slow, the Germans stubbornly giving ground. An estimated 60,000 Allied troops died in the eighteen months of that gruelling campaign. Lorna was seeing the fallout from the vicious and relentless fighting taking place at Salerno, Taranto and Bari. Convoys of wounded were arriving at all times of day and night.

I have … supervised and organised up to 88 operations in one day. The hope, agony and suffering on those faces spurred one on …

It was flat out – time was of the essence and we had no penicillin then. That was shortly to come. The impossible became possible, stretchers lined the corridors outside the theatre – life had to be saved … Very often we’d crawl off in the grey dawn to re-appear for duty the next day.

One pitch-dark night she stumbled while crossing the courtyard back to the huts and fell up to her waist in icy-cold liquid mud. ‘I could not move, just sat there and cried with sheer exhaustion and helplessness … Momentarily I nearly broke. I was as near to hysteria as I’ve ever been.’ An ambulance driver rescued her and took her back. Going to bed took ages. The temperatures were so icy that you had to bundle yourself up in layers of clothes before climbing under the blankets. Then no sooner were you dropping off than the knock on the door would come, and the cry, ‘Convoy!’

You asked no questions – out into the night – hurry, hurry – men are dying.

It was Lorna’s boast that, despite nursing under these conditions, she never neglected a patient.

But she also noted that the hardships were unfairly distributed between men and women. It wasn’t just the toilets, though they were bad enough (and the Medical Corps were billeted comfortably in a hotel). Orderlies didn’t always take kindly to being given instructions by a woman. One in particular consistently reacted to her commands with dumb insolence. It wasn’t until she demonstrated her exceptional cool-headedness, resuscitating a dying patient in transit between theatre and ward, that this man got the message. ‘ “My God,” he said “that was wonderful – I will never question your authority again” and he never did, and became one of my great champions.’

At the other end of the scale was Charles, the senior surgeon, who relentlessly needled and patronised Lorna, bombarding her with crude jokes and insults. Only the support of her fellow staff made this endurable. Mutual respect was temporarily re-established when the two of them shared the agony of the most dangerous surgical operation either had ever witnessed. A German was admitted with a three-inch unexploded shell lying just beneath the outer membrane of his heart. He was alive, but removing the shell might cause it to explode, killing everyone. Despite this, it was decided to go ahead; Lorna would assist alongside the anaesthetist, and a disposal expert would be on hand to defuse the shell. Lorna’s knees shook as she watched Charles make the incision and open the wound; she could see the shell as it had appeared in the X-ray, bulging just below the man’s heart. With meticulous care Charles eased the tissue away to expose it; everyone knew his instruments might detonate it at any moment. He worked away until at last the shell was sufficiently revealed, then drew it deftly out and handed it to Lorna. ‘He placed it on my outstretched hand. What a moment!’ She passed it to the disposal officer, who calmly took it outside and slid it into a bucket of water, to be taken off and defused, two miles away. ‘It was a miracle. The shell had in no way damaged the heart.’ Charles turned to Lorna and said, ‘Thank you, that was wonderful,’ and she acknowledged his skill with newfound awe. Often, later, she would wonder whether the German ever realised that British medics had heroically risked their lives to save his. Unfortunately it wasn’t long before Charles reverted to the uncouth rudeness that she’d become accustomed to.

In Italy Lorna Bradey’s feelings ricocheted between the near hysteria induced by overwork and poor conditions, and elation at the good times. She was living at a peak of intensity. Henry, a boyfriend from the North African campaign, now showed up at Barletta. Off-duty she’d ride with him in his station wagon to secluded beaches, where they swam and ate picnics under the stars. Cut loose from pressures, these were magical interludes. White-crested breakers pounded the beach as they danced to Bing Crosby singing ‘White Christmas’ on Henry’s old wind-up gramophone. The salt wind tousled his hair; there’d be bacon and eggs frying on a primus.

Neither of us expected it to last for ever … We’d agreed to make no demands on one another, realising there was so much ahead and that we would be separated again and again.

In Henry’s absence Lorna partied with the rest of them, taking the rough with the smooth. ‘The tensions were terrific.’ Once, an RAF officer who’d drunk too much vino tried to rape her. He’d ripped most of her clothes off and got his trousers open before she yelled at him that she would jump from the sixth floor if he went any further. Fortunately, the threat was enough to deter him. In March 1944 Vesuvius erupted. Over Bari the bright morning suddenly darkened as fragments of hot ash fell from the sky. Lorna and her pal Bobby took a week’s leave and hitch-hiked to Sorrento. They saw the volcano smoking ominously across the blue bay, fiery lava still pouring out, mowing down the lemon groves in its path. They visited Pompeii, and Capri – a ‘week of paradise’ – and then it was back to Barletta. Convoys of wounded from the bloodbath at Monte Cassino were arriving every day. The week’s leave was over. Lorna was now so exhausted it was as if she had never been away.

By this time, she and her comrades had become a tightly knit, extraordinarily efficient unit, and Lorna was proud of what they did. But the stress was wearing her down. One day the CO – ‘a charming Irishman’ – summoned her. With great tact and gentleness he questioned her about the demands of her job at Barletta:

Gradually the sluice gates opened and out it all came …

the hard grind, their accommodation, and above all the rudeness of Charles the Senior Surgeon …

I tried to be evasive – said he was a good surgeon etc. … [and] here was someone in authority being kind and understanding – I broke down – all the tensions released …

He was astonished.

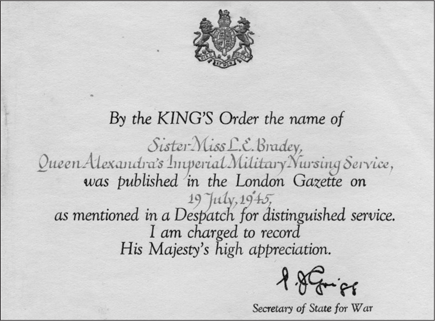

The colonel listened carefully. It was obvious that much of what Lorna was telling him was news, but his considered response, when it came, showed that he had been thinking about her needs. She was to be promoted to deputy matron at a 2,000-bed hospital in Andria, 10 miles away. In addition, her unstinting service was to be recognised by an official military accolade detailing her noteworthy conduct: she was to be ‘Mentioned in Despatches’. The honour of this was not lost on Lorna. She had spent long enough with the army to know that normally this was an award conferred on soldiers for gallantry in the field. Why had she been singled out?

Did I really deserve it? What about all the others?

Lorna knew only too well the dedication of her fellow QAs and their stoical endurance.

He gave me a big hug. ‘You represent all of them my dear.’

At last, following the decrypting by Hut 8 at Bletchley of the U-boats’ Enigma in December 1942, the Battle of the Atlantic was starting to go against the Germans. The French Resistance was gathering force. In Russia, Soviet forces were on the offensive, gaining ground around Stalingrad. The RAF were bombarding German cities.

Honoured for her distinguished service, Sister Lorna Bradey was ‘Mentioned in Despatches’.

These dramatic developments had great significance for the war as a whole. But for many back in Britain catastrophes and explosions on distant oceans and in faraway cities were little more than background noise. In the summer of 1943 eighteen-year-old Nina Mabey, for all her newfound political awareness, was more preoccupied by her personal progress than by the prospect of a Second Front. That August she was on a Shropshire farm with her mother, cleaning out the pigsty, when the letter arrived informing her that she had won a scholarship to Somerville College Oxford. She went up to read French in October.

In the autumn of 1943, Oxford slept in a strange and timeless silence.

War had silenced the city’s bells, making the spires seem more than usually dreamy and peaceful. Nina’s life revolved around her academic work – she soon dropped French in favour of Politics, Philosophy and Economics – and abstract yearnings for romance.

Our war barely touched us.

Nina’s entire adolescence had been played out with war as a background; she could barely recall a time when the blackout, rationing and war work had not been part of her everyday life. She helped with expected duties at her college, manning the stirrup-pump team with the rest and fire-watching on the roof of the Bodleian; but reading Wittgenstein, dances, skinny-dipping in the Cherwell, dons, dates and debates all held Nina Mabey in far greater thrall than events in the wider world.

For most women on the home front the war was more about deprivation and anxiety than bombs and battles. Shirley Goodhart wrote almost daily of her impatience for it all to end. Jack, her husband, had been away in India for over a year, and she longed for him daily, feeling ‘miserable and husbandless’. The knowledge that Jack was safe, stationed with the Royal Army Medical Corps in India, helped, but only a bit, especially when she heard from him on leave in Kashmir.

It’s a strange war that sends Jack almost to lead a life of very little work, good food, good pay and good holidays, and leaves me here to work hard and lead a drab wartime existence …

I don’t want to have to sit all day in the office … and I’m suddenly desperately lonely and want my husband.

Britain was no longer in the front line, and the faraway fighting seemed only to intensify the frustration of life on the home front.

Margery Baines (née Berney) had married precipitately in 1940, and after a brief honeymoon her husband was posted abroad. Margery was far too impulsive and ambitious to endure the role of a Penelope, pining and lonely. ‘By nature I was a leader.’ Her high-octane manner secured her a place in an Officer Cadet Training Unit, but by late 1943 the army’s brutality, pomposity and red tape were testing her loyalty to its limits. By then she had not only encountered the usual shocks attendant on army life – lice and fleas, filthy lavatories, stinking dormitories, bluebottle-infested kitchens, all ‘terrifying to a young girl who has been sheltered from the realities of a classless society’ – she had also run up against corrupt authority, inhumanity and victimisation. When her captain took a dislike to her and rejected her for a commission, Margery appealed and got the decision revoked. She was sent off to run a platoon in Aylesbury. But even now she was up against the inflexibility and mindless discipline of her commanding officers. ‘I believed [my girls] would work better if I could wring certain advantages for them out of the rigid system. But I have to confess that most of the time it was failure right down the line.’

In fact, Margery’s time as a Welfare Officer with the ATS would fuel her invincible determination to make something of herself, at the same time as giving her invaluable lessons in overcoming defeat, fighting for the underdog, and giving tireless consideration to those under her command. The battles she would later undertake would not involve guns or explosives, but, after the war, Margery’s assertive spirit and her army experiences would not go to waste.

*

Fears of invasion had receded. Despite continuing air raids, the full-on Blitz seemed like history. Churchill had promised that – though the end was not in sight – it was, inexorably, coming. Slowly but surely the phrase ‘after the war’ began to be used with cautious optimism. ‘People talk about the end of the war as though it were a perfectly matter-of-fact objective on the horizon and not just a nice pipe dream,’ wrote Mollie Panter-Downes at this time.

Hopes for the future were surfacing, irrepressibly, breaking through the gloom of everyday life.

Up in Kintyre, Naomi Mitchison took a robust attitude to present hardships and directed her powers to improving the lot of local women. Briskly, she set off to talk to the Scottish Education Department about getting adult women back into college after the war. ‘I am full of ideas about it.’ Intelligent women were going to waste; their unexpended energies could be harnessed for the good of the community. Naomi herself was endlessly active on committees and in meetings, working tirelessly to promote causes allied to post-war reconstruction, such as a scheme for Scottish hydro-electricity.

But more usually, imagining a world beyond wartime involved finding ways to make up for all the deprivations. Land girl Kay Mellis’s dreams revolved around new clothes:

If you really wanted a dress, and you didn’t have the coupons … well, I used to think, you know, when the war’s finished I’m going to buy material and I’m going to make myself a new dress.

That was what we saw the future as being. A free life, being able to go into the shops and buy materials and make things, or buy a couple of pairs of shoes.

And my friend Connie – she was a great knitter. She was going to knit for Scotland, and I was going to sew for Scotland.

When they thought about their own role, most women focused on the fulfilment of domestic aspirations. Lovely breakfasts were what Clara Milburn missed: coffee, butter and marmalade, though above all she looked forward to her son Alan’s return. After three years in the FANYs Patience Chadwyck-Healey, exhausted by the lack of privacy, yearned for a rural retreat. ‘I just wanted to grow roses in a little cottage miles away on top of a hill somewhere – utter peace and flowers and relaxation – that was what I thought would be absolutely gorgeous.’

Thus, for most, the principal preoccupations were the traditionally feminine concerns of home and hearth. In 1944 the author Margaret Goldsmith set out to inquire on women’s wartime state of mind. Many wives, she reported, ‘are so homesick for their pre-war way of life that they seem to have created in their imagination a glowing fantasy of what this life was like. All the small yet grinding irritations of domesticity are forgotten.’

But what would the reality be in that longed-for home, in that imagined dream-time ‘after the war’? The millions of women who had taken on war work or been conscripted knew that the world they’d grown up in would never be the same again. They would still be mothers, housewives, feeders, healers, carers and educators. But after so much sacrifice, they wanted to believe that life after the war would be better than what had gone before.

So when, on 2 December 1942, the liberal social reformer Sir William Beveridge published a report which promised a ‘comprehensive policy of social progress’, the women of Britain turned eagerly to its pages to discover what plans their leaders had to improve their lot. Was it possible that the government was starting to recognise that half the population of Britain lived lives of unaided struggle, and that there existed a genuine political will to assist and support their efforts?

That evening, Nella Last listened to Sir William broadcasting to the nation as he laid out a utopian vision. In the new, post-war world Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness would be regarded as the evils of a past age. He explained with care the workings of a contributory scheme which would supply a comprehensive safety net covering all eventualities, for the entire population. There would be Family Allowances, a National Health Service and National Assistance for the unemployed. The pioneering scheme offered everything from maternity grants to funeral grants, ‘from the cradle to the grave’.

‘Never since I first listened to a speaker on the air have I felt as interested as I was tonight by Sir William Beveridge,’ reported Nella. His broadcast left her feeling profoundly hopeful about the future. The scheme would surely make a huge difference to women: ‘It is they who bear the real burden of unemployment, sickness, child-bearing and rearing – and the ones who, up to now, have come off worst. There should be some all-in scheme.’ As she wrote up her diary that night, Nella was struck by how Beveridge’s proposals seemed in so many ways to chime with her own deepest aspirations. She recalled pre-war days when she would discuss social issues with her sons and their friends. Back then her proto-feminism had not gone down well: ‘[They] thought I was a visionary when I spoke of a scheme whereby women would perhaps get the consideration they deserved from the State.’ But could this be her vision coming true?

Yes, war could change things for the better. Nella Last had no regrets about the pre-war days; she knew all about want, disease and squalor. There was dreadful poverty in Barrow during the Depression. Wages were so low that children in the town went barefoot; and they all had toothache, because their parents were too poor to send them to have their teeth pulled. Impetigo was rife – the kids were scabbed and raw from it. The husbands were tyrannical when it came to money. They spent their wages on cheap beer, yet held their wives to account for every penny.

It now dawned on Nella how selfish Will, her husband, could be, how he had never made provision for his dependants in the event of his death, or paid for insurance, or given her decent housekeeping money. And now here he was complaining that, under the new scheme, he would have to work till he dropped. Nella felt angry. She didn’t want to be ‘cared for’ by her husband; she wanted to be appreciated and she wanted some understanding of how housewives like her were always on the sharp end when things got difficult. Will Last was simply unaware of what narrow margins his hard-worked wife survived on. Her husband’s tight-fistedness left her having to subsidise the children’s welfare with what she could save from the housekeeping. When sickness struck, or an operation had to be paid for, life became tough indeed. If implemented, Beveridge’s proposals would sweep away all this hardship. From now on, something started to change in this fifty-two-year-old housewife from Barrow-in-Furness. Nella’s Mass Observation diaries track a growing contempt for her husband, a rage at his dismissive attitude towards her and a gathering sense of her own value and talents. ‘I’m beginning to see I’m a really clever woman in my own line, and not the “odd” or “uneducated” woman that I’ve had dinned into me,’ she wrote.

The Beveridge Report sold over 600,000 copies. Mollie Panter-Downes reported to her New York readers that Londoners had queued up to buy the doorstop manual for two shillings, ‘as though it were unrationed manna dropped from some heaven where the old bogey of financial want didn’t exist’. These avid purchasers had read it with new optimism:

The plain British people, whose lives it will remodel, seem to feel that it is the most encouraging glimpse to date of a Britain that is worth fighting for.

For Nella Last, and for many others, the Report read as a manifesto for women, a true attempt to offer them a better future.

Though the Beveridge report continued to be kicked around parliament like a football for the remainder of the war, its huge popularity ensured that no government could now duck out of the post-war creation of a welfare state. Family allowances would become a reality; there would be a National Health Service. Hopes soared that scrimping and saving, drunk tyrannical husbands and scabby barefoot children with rotten teeth would all become distant memories. The bitter sacrifices of housewives across the nation had, it seemed, gained some official recognition at last.