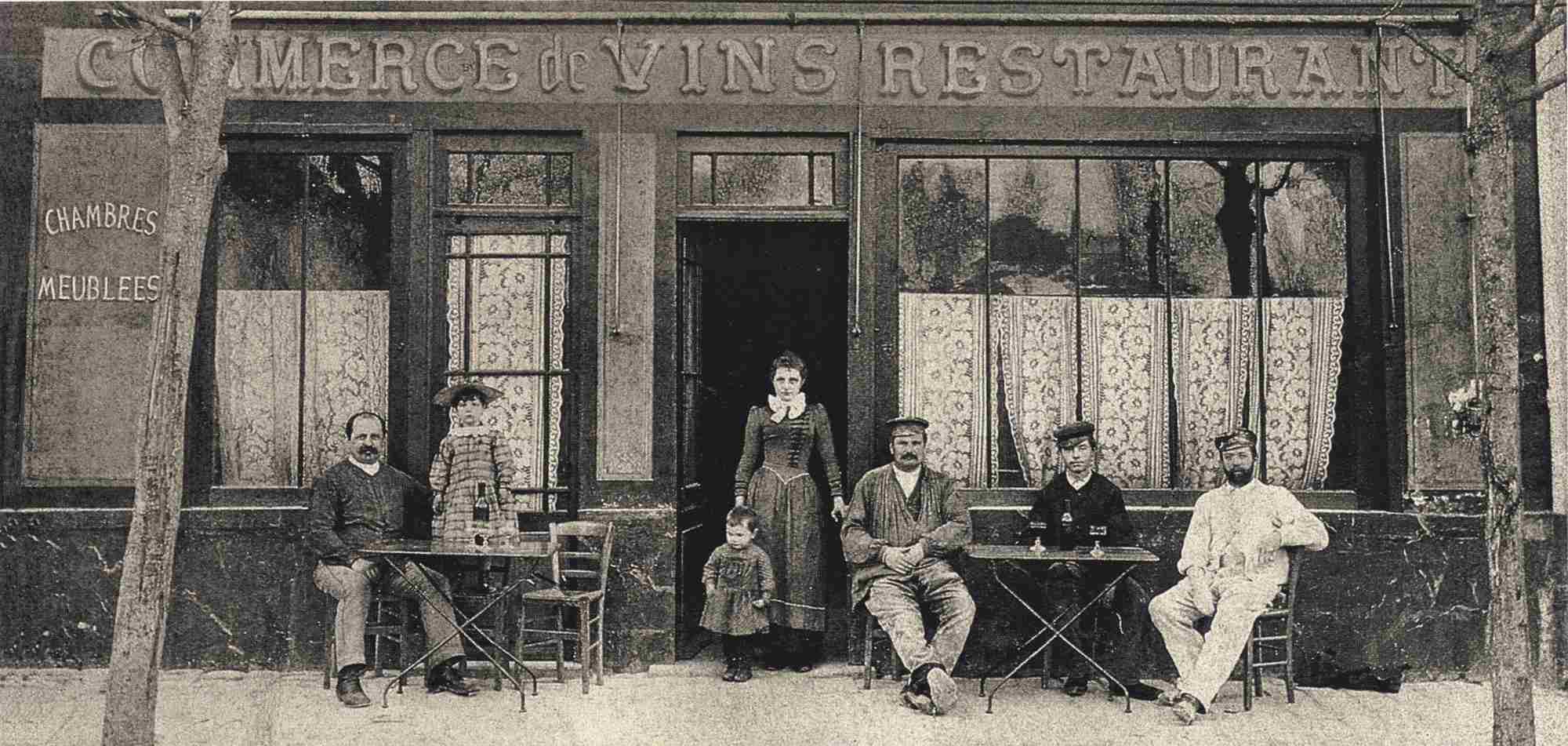

Café on place de la Mairie (now Auberge Ravoux), Auvers-sur-Oise

Van Gogh began to entertain hopes of leaving the asylum in Saint-Rémy and spending some time in the north of France. There were two options: finding another clinic where he would be allowed to work, or going to live near someone who would keep an eye on him. Theo found a doctor willing to do this in Auvers-sur-Oise, a rural village about thirty kilometres north of Paris, on the banks of the river Oise. Even though Van Gogh suffered another attack in April, he recovered with remarkable speed and did not want to wait longer than necessary to arrange his departure from Saint-Rémy.

Van Gogh viewed his stay in the south as a fiasco, but he left in the conviction that he had, in the end, managed to create a series of works that, taken altogether, truly reflected the character of Provence: the colour, nature, the landscape, the people. Greatly relieved, he took the train to Paris on 16 May 1890.

Vincent stayed briefly in Paris with Theo, Jo and their baby Vincent Willem, and met several acquaintances, but it soon became too much for him. On 20 May he took the train for Auvers. He lodged at the café on the place de la Mairie, run by Arthur Ravoux and his wife Adeline. He soon struck up a friendship with Paul Gachet, the doctor whom Pissarro had recommended. Gachet was also an amateur artist, and took Vincent under his wing. Over the next two months Van Gogh painted and drew with the utmost intensity, producing remarkable landscapes and portraits.

In Auvers, all had seemed well. Van Gogh was working hard, some articles had appeared in the press about his paintings, and many people had now seen his work. Gauguin had written to him, saying ‘you have never worked with so much balance while conserving the sensation and the interior warmth needed for a work of art’ (884), and Theo had been equally encouraging: ‘you have found your path, old brother, your carriage is already sturdy and strong.’ (894)

Café on place de la Mairie (now Auberge Ravoux), Auvers-sur-Oise

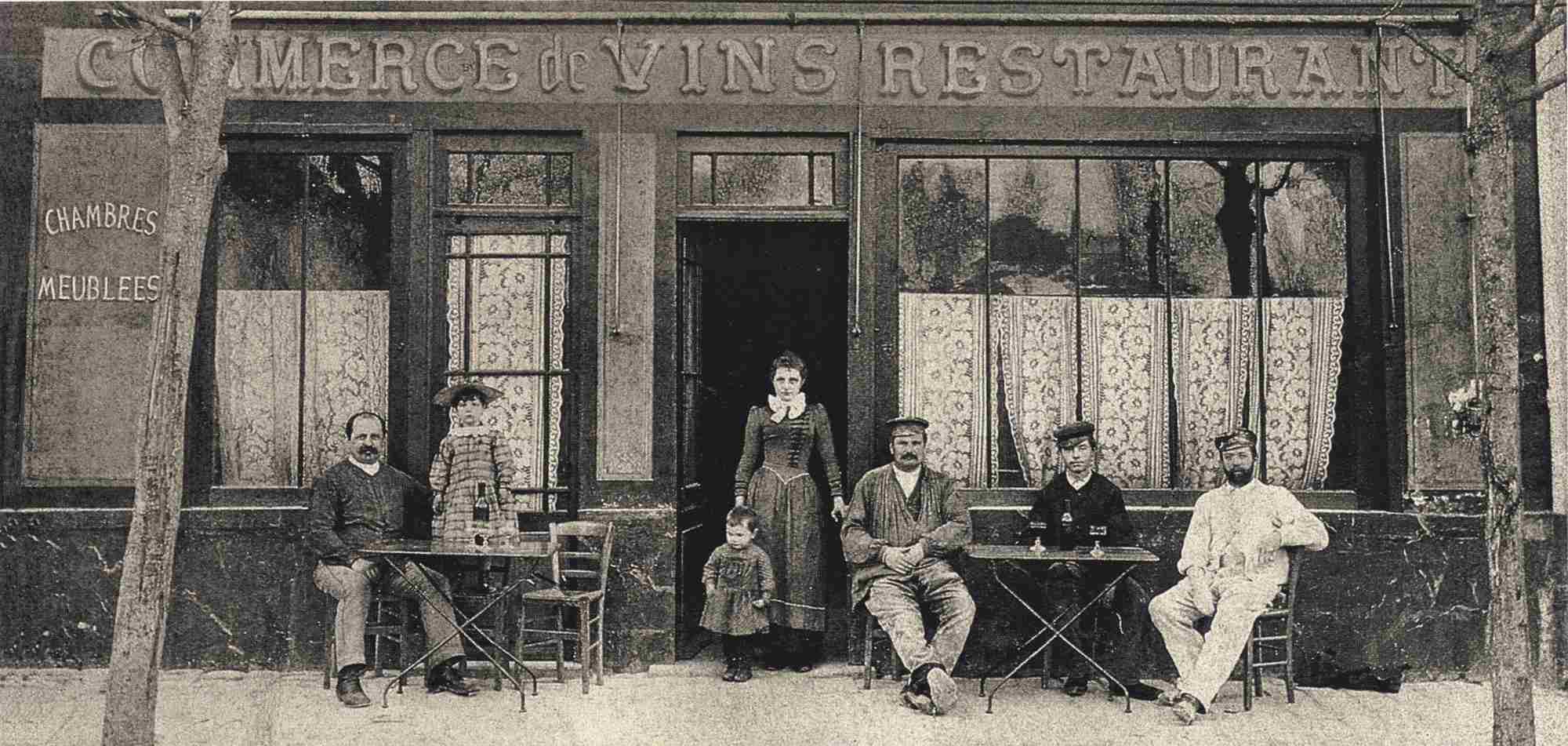

Jo van Gogh-Bonger, Theo’s wife, with their son Vincent Willem, April 1890

There seemed to be good reasons to be every bit as positive about Vincent’s health. Dr Gachet had told Theo in early June that he thought Vincent cured, and Vincent himself wrote to Theo and Jo that in Auvers ‘the nightmare’ has ceased ‘to such an extent’ (881). In the middle of July, Vincent wrote to his mother and sister Wil that ‘the turmoil in my head has really abated so much.’ (899)

However, quite a few uncertainties and tensions remained. Theo wrote to Vincent, telling him that he was worried about his position at Boussod, Valadon & Cie, and about his baby son’s poor health. He considered resigning from the firm and starting up as an independent art dealer, but failed to gain the necessary backing from the Van Gogh uncles in Holland. In June, Theo took Jo and the baby to visit Vincent, and he, in turn, came to see them in Paris. On 6 July, a conversation took place in Theo and Jo’s apartment at which Andries Bonger and Vincent were also present. Bonger – Jo’s brother, and a friend of Theo – declared himself unwilling to enter into a business partnership, dashing Theo’s hopes of setting up as an independent dealer. Theo’s professional problems, the baby’s illness and tensions between Jo’s brother and sister-in-law complicated the visit. Jo later felt that she had been unfairly impatient with Vincent, who had become anxious to leave.

On Sunday, 27 July 1890, Van Gogh went to paint in the fields outside Auvers. At some point he decided to put an end to his life. The immediate cause and precise circumstances are unknown, but it is clear that he had little faith in the future, despite his passion for work. He shot himself in the chest with a pistol (it is not known how he got hold of it) and lost consciousness. When he came round, he managed somehow to return to Ravoux’s café. Help was summoned, but nothing could be done to prevent his death in the early morning of 29 July.

To Theo van Gogh (letter 877)

My dear Theo,

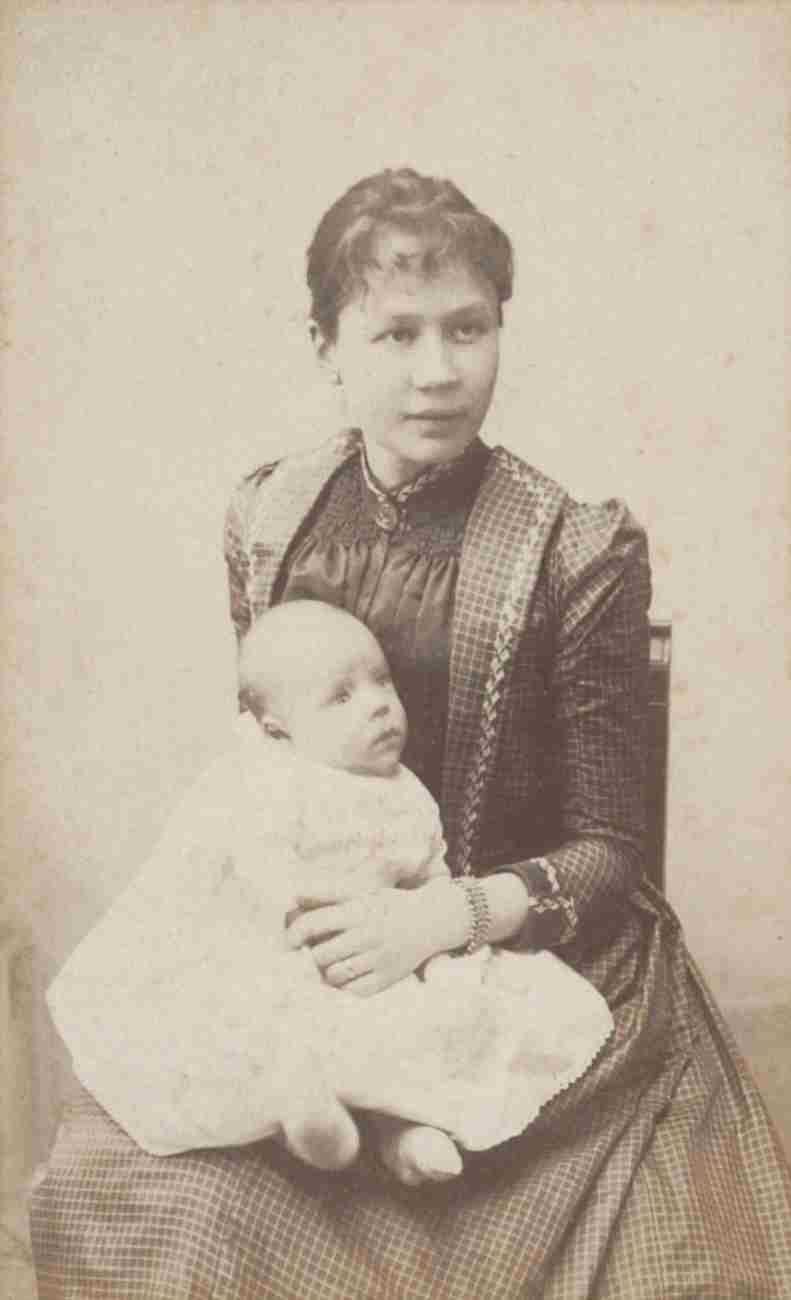

For several days now I’d have liked to write to you with a rested mind, but have been absorbed in work. This morning your letter arrives, for which I thank you and for the 50-franc note it contained. Yes, I think that it would be good for many reasons that we were all together again here for a week of your holidays, if longer isn’t possible. I often think of you, Jo and the little one, and I see that the children here look well in the healthy fresh air. And yet it’s difficult enough to raise them, even here, all the more is it rather terrible sometimes to keep them safe and sound in Paris on a fourth floor. But anyway, one must take things as they are. Mr Gachet says that father and mother must feed themselves quite naturally, he talks of taking 2 litres of beer a day &c., in those amounts. But you’ll certainly enjoy furthering your acquaintance with him, and he’s already counting on it, speaks of it every time I see him, that you’ll all come. He certainly appears to me as ill and confused as you or I, and he’s older and a few years ago he lost his wife, but he’s very much a doctor, and his profession and his faith keep him going however. We’re already firm friends, and by chance he also knew Bruyas of Montpellier and has the same ideas on him as I have, that he’s someone important in the history of modern art. I’m working on his portrait [sketch A] the head with a white cap, very fair, very light, the hands also in light carnation, a blue frock coat and a cobalt blue background, leaning on a red table on which are a yellow book and a foxglove plant with purple flowers. It’s in the same sentiment as the portrait of myself that I took when I left for here.

877A. Doctor Gachet

Mr Gachet is absolutely fanatical about this portrait, and wants me to do one of him if I can, absolutely like that, which I also wish to do. He has now also come to understand the last portrait of the Arlésienne, one of which you have in pink – he comes back all the time, when he comes to see the studies, to these two portraits and he accepts them fully, but fully as they are. I hope to send you a portrait of him soon. Then I painted two studies at his house which I gave him last week. One aloes with marigolds and cypresses, then last Sunday white roses, vines and a white figure in it.

I’ll very probably also do the portrait of his daughter, who is 19, and with whom I can easily imagine Jo will quickly make friends.

So I’m looking forward to doing the portraits of all of you in the open air, yours, Jo’s and the little one’s.

I still haven’t found anything interesting in the way of a possible studio, and yet I’ll have to take a room to put in the canvases which are surplus at your apartment and which are at Tanguy’s. For they still need a great deal of retouching. But anyway, I live from day to day – the weather is so fine. And my health is good, I go to bed at 9 o’clock but I get up at 5 o’clock most of the time.

I have hopes that it won’t be disagreeable to be together again after a long absence. And I also hope that I’ll continue to feel much surer of my brush than before I went to Arles. And Mr Gachet says that he would consider it highly improbable that it should recur, and that it’s going completely well. But he, too, complains bitterly of the state of things everywhere in the villages where the least foreigner has come, that life there becomes so horribly expensive. He says that he’s astonished that the people where I am lodge and feed me for that, and that I’m still fortunate, compared to others who have come and whom he’s known. That if you come, and Jo and the little one, you can’t do better than stay at this same inn. Now nothing, absolutely nothing keeps us here but Gachet – but the latter will remain a friend, I’d assume. I feel that at his place I can do not too bad a painting every time I go there, and he’ll certainly continue to invite me to dinner each Sunday or Monday.

But up to now, however agreeable it is to do a painting there, it’s a chore for me to dine and lunch there for, the excellent man goes to the trouble of making dinners in which there are 4 or 5 courses, which is as abominable for him as it is for me, for he certainly doesn’t have a strong stomach. What has held me back a little from saying something about it is that I see that, for him, it reminds him of the days of yore when people had family dinners, which anyway we too well know.

But the modern idea of eating one, at most two courses is, however, certainly progress, and a healthy return to true antiquity.

Anyway père Gachet is a lot, yes a lot like you and I. I was pleased to read in your letter that Mr Peyron asked for news of me when he wrote to you. I’m going to write to him this very evening that things are going well, for he was very kind to me and I’ll certainly not forget him. Dumoulin, the one who has Japanese paintings at the Champ de Mars, has come back here, and I very much hope to meet him.

What did Gauguin say about the last portrait of the Arlésienne that’s done after his drawing? You’ll end up seeing, I would think, that it’s one of the least bad things I’ve done. Gachet has a Guillaumin, naked woman on a bed, which I consider very beautiful, he also has a very old Guillaumin portrait by him, very different from ours, dark but interesting.

But his house, you will see, is full, full like an antique dealer’s, of things that aren’t always interesting, it’s terrible, even. But in all of this there’s this good aspect, that there would always be what I need there for arranging flowers or still lifes. I’ve done studies for him, to show him that should he not be paid in money we’ll nevertheless still compensate him for what he does for us.

Do you know an etching by Bracquemond, the portrait of Comte, it’s a masterpiece.

I’d also need as soon as possible 12 tubes zinc white from Tasset and 2 medium tubes geranium lake.

Then as soon as you could send them I’d be absolutely set upon copying all of Bargue’s Etudes au fusain again, you know the nude figures. I can draw them quite quickly, let’s say the 60 sheets that there are in a month, so you might send a copy on loan, I’d make sure not to stain or dirty it. If I neglected to keep on studying proportions and the nude I’d find myself in a bad position later on. Don’t think this absurd or futile.

Gachet also told me that if I wanted to give him great pleasure he would like me to redo for him the copy of Delacroix’s Pietà, which he gazed at for a long time. Later he’ll probably give me a hand with the models, I feel that he’ll understand us completely, and that he’ll work with you and me without reservation, with all his intelligence, for the love of art for art’s sake. And he’ll perhaps have me do some portraits. Now to have clients for portraits one must be able to show different ones that one has done. That’s the only possibility I can see of placing something. But however, however, certain canvases will one day find collectors. Only I think that all the fuss created by the large prices paid lately for Millets &c. has further worsened the state of things as regards the chance one has of merely recouping one’s painting expenses. It’s enough to make one dizzy. So why are we thinking about it, it would stupefy us. Better still, perhaps, to seek a little friendship and live from day to day. I hope that the little one will continue to be well, and you two also until we see each other again, more soon, I shake your hand firmly.

Vincent

To Willemien van Gogh (letter 879)

My dear sister,

I ought to have replied to your two letters long since, which I received while still in St-Rémy, but the journey, work and a host of new emotions up to today made me put it off from one day to the next. It interested me very much that you’ve cared for patients at the Walloon hospital, that’s certainly how one learns heaps of things, the best and most necessary that one can learn, and I myself regret that I know nothing, in any event not enough, about all that.

It was a great happiness for me to see Theo again, to meet Jo and the little one. Theo was coughing more than when I left him more than 2 years ago, but while talking and when I saw him at close hand, however, I considered him certainly rather changed for the better, all things considered, and Jo is full of both good sense and good will. The little one is not sickly, but not strong either. It’s a good system that if one lives in a large town the woman gives birth in the country and spends the first months there with the little one. But there you are, for the first time especially, as the birth is frightening, they certainly couldn’t have done better or otherwise than they did. I hope that they’ll come here to Auvers for a few days soon.

For me the journey and the rest up to now have gone well, and coming back to the north distracts me a lot. Then I’ve found in Dr Gachet a ready-made friend and something like a new brother would be – so much do we resemble each other physically, and morally too. He’s very nervous and very bizarre himself, and has rendered much friendship and many services to the artists of the new school, as much as was in his power. I did his portrait the other day and am also going to paint that of his daughter, who is 19. He lost his wife a few years ago, which has greatly contributed to breaking him. We were friends, so to speak, immediately, and I’ll go and spend one or two days a week at his house working in his garden, of which I’ve already painted two studies, one with plants from the south, aloes, cypresses, marigolds, the other with white roses, vines and a figure. Then a bouquet of buttercups. With that I have a larger painting of the village church – an effect in which the building appears purplish against a sky of a deep and simple blue of pure cobalt, the stained-glass windows look like ultramarine blue patches, the roof is violet and in part orange. In the foreground a little flowery greenery and some sunny pink sand. It’s again almost the same thing as the studies I did in Nuenen of the old tower and the cemetery. Only now the colour is probably more expressive, more sumptuous. But in the last few days at St-Rémy I worked like a man in a frenzy, especially on bouquets of flowers. Roses and violet Irises.

For Theo and Jo’s little one I brought back a rather large painting — which they’ve hung above the piano – white almond blossoms – big branches on a sky-blue background, and in their apartment they also have a new portrait of an Arlésienne. My friend Dr Gachet is decidedly enthusiastic about this latest portrait of the Arlésienne, one of which I also have myself, and about a portrait of myself, and that gave me pleasure, since he’ll drive me to do figure work and I hope he’ll find me a few interesting models to do. What I’m most passionate about, much much more than all the rest in my profession – is the portrait, the modern portrait. I seek it by way of colour, and am certainly not alone in seeking it in this way. I would like, you see I’m far from saying that I can do all this, but anyway I’m aiming at it, I would like to do portraits which would look like apparitions to people a century later. So I don’t try to do us by photographic resemblance but by our passionate expressions, using as a means of expression and intensification of the character our science and modern taste for colour. Thus the portrait of Dr Gachet shows you a face the colour of an overheated and sun-scorched brick, with a reddish head of hair, a white cap, in surroundings of landscape, blue background of hills, his suit is ultramarine blue, this brings out the face and makes it paler, despite the fact that it’s brick-coloured. The hands, hands of an obstetrician, are paler than the face.

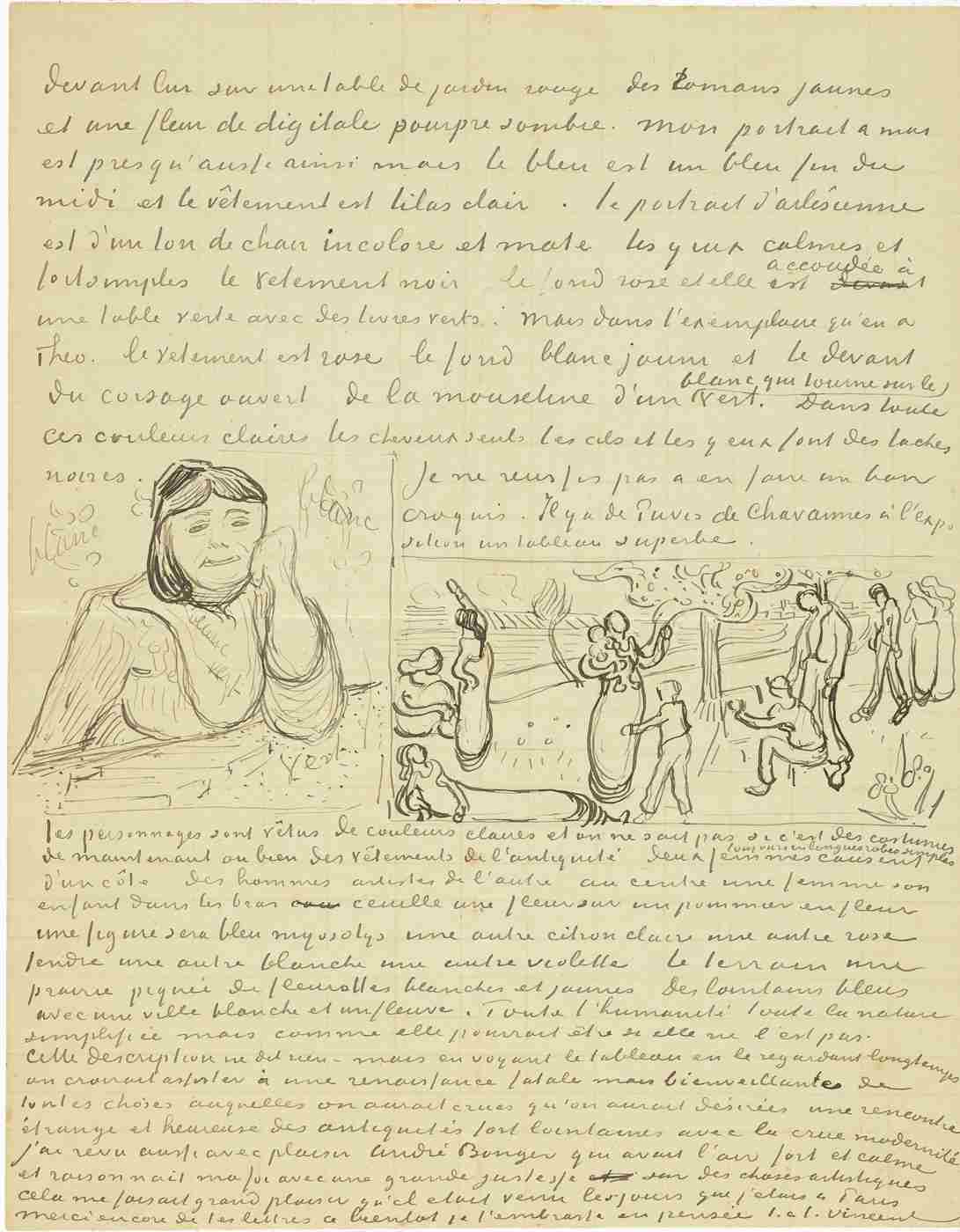

Before him on a red garden table yellow novels and a dark purple foxglove flower. My portrait of myself is almost like this too, but the blue is a fine southern blue and the suit is light lilac. The portrait of the Arlésienne is of a colourless and matt flesh tone, the eyes calm and very simple, the clothing black, the background pink, and she’s leaning her elbow on a green table with green books. But in the one Theo has, the clothing is pink, the background yellow-white, and the front of the open bodice is of white muslin, verging on the green. In all these bright colours, only the hair, the eyelashes and the eyes form dark patches. [sketch A] I can’t manage to do a good croquis of it.

At the exhibition there’s a superb painting by Puvis de Chavannes.

[sketch B] The figures are dressed in bright colours and one doesn’t know if they’re costumes from now or clothes from antiquity; two women are talking (also in long, simple dresses). On one side, artistic-looking men on the other, in the centre a woman, her child in her arms, is picking a flower from an apple tree in blossom. One figure will be forget-me-not blue, another bright lemon, another soft pink, another white, another violet, the ground a meadow dotted with little white and yellow flowers. Blue distance with a white town and a river. All humanity, all nature simplified, but how it could be, if it isn’t already.

879A–B (left to right). Marie Ginoux (‘The Arlésienne’); sketch after Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Inter artes et naturam (Between art and nature)

This description doesn’t say anything – but by seeing the painting, by looking at it for a long time one would think one was present at an inevitable but benevolent rebirth of all things that one might have believed in, that one might have desired, a strange and happy meeting of the very distant days of antiquity with raw modernity.

I was also pleased to see André Bonger again; he looked strong and calm, and my word reasoned with great accuracy on artistic things, it pleased me very much that he’d come during the days when I was in Paris.

Thank you again for your letters, more soon, I kiss you in thought.

Ever yours,

Vincent

To Theo van Gogh and Jo van Gogh-Bonger (letter 896)

My dear Theo and dear Jo.

I’ve just received the letter in which you say that the child is ill; I’d very much like to come and see you, and what holds me back is the thought that I’d be even more powerless than you are in the given state of distress. But I can feel how very exhausting it must be, and would like to be able to lend a hand. By coming straightaway I fear I would increase the confusion. However, I share your anxieties with all my heart. It’s a real pity that at Mr Gachet’s the house is so cluttered with all sorts of things. Otherwise I think it would be a good plan to come and lodge here – at his house – with the little one, at least for a good month – I think that the country air has an enormous effect. In the street here there are kids born in Paris and really sickly – who however are well. Coming here to the inn would be possible too, it’s true. So that you aren’t too alone I could come myself to stay at your place for a week or fortnight.

That wouldn’t increase the expenses. For the little one, truly I’m beginning to fear that he must be given air, and especially the little bustle of the other children of a village. Surely, Jo too, who shares our anxieties and risks, I think that from time to time she must take this distraction of the country.

A rather melancholy letter from Gauguin, he talks vaguely of having definitely decided on Madagascar, but so vaguely that one can clearly see that he’s only thinking of it because he doesn’t really know what else to think about. And the execution of the plan seems almost absurd to me.

[sketch A – C] Here are three croquis – one of a figure of a peasant woman, big yellow hat with a knot of sky-blue ribbons, very red face. Coarse blue blouse with orange spots, background of ears of wheat.

896A–C (left to right, top to bottom). Girl against a background of wheat; Couple walking between rows of poplars; Wheatfields

It’s a no. 30 canvas but it’s really a little coarse, I fear. Then the horizontal landscape with the fields, a subject like one of Michel’s – but then the coloration is soft green, yellow and green-blue. Then undergrowth, violet trunks of poplars which cross the landscape perpendicularly like columns. The depths of the undergrowth are blue, and under the big trunks the flowery meadow, white, pink, yellow, green, long russet grasses and flowers.

The people here at the inn used to live in Paris; there they were constantly indisposed, parents and children, here they never have anything, and especially not the littlest one which came here when it was 2 months old, and then the mother had difficulty in suckling him, while here all of that went well almost immediately. In another respect you work all day long, and at the moment you’re probably hardly sleeping. I’d willingly believe that Jo would have twice as much milk here, and that then when she came here one could do without cows, donkeys and other quadrupeds. And as for Jo, so that during the daytime she has company, my word, she could also go and stay just opposite père Gachet, perhaps you remember that there’s an inn just opposite at the bottom of the slope.

What do you want me to say as regards the future, perhaps, perhaps, without the Boussods?

What will be, will be, you haven’t spared yourself trouble for them, you’ve served them with an exemplary fidelity all the time.

I, too, am trying to do as well as I can, but I don’t hide from you that I scarcely dare count on always having the necessary health.

And if my illness recurred you would excuse me, I still love art and life very much, but as to ever having a wife of my own I don’t believe in it very strongly. I fear, rather, that towards let’s say the age of forty –

but let’s not say anything – I declare that I know nothing, absolutely nothing, of what turn it may yet take.

But I’m writing to you at once that as regards the little one I think you mustn’t worry yourselves excessively; if it’s that he’s teething, well to make the task easier for him perhaps we could distract him more here where there are children, animals, flowers and good air.

I shake your hand and Jo’s firmly in thought, and kiss the little one.

Ever yours,

Vincent

Thank you for the consignment of colours, for the 50-franc note and for the article on the Independents.

An Englishman, Australian, called Walpole Brooke will probably come to see you; he lives at 16 rue de la Grande Chaumière – I told him that you would let him know a time when he could come and see my canvases that are at your place.

He’ll probably show you some of his studies, which are still rather lifeless, but however he does observe nature. He has been here in Auvers for months, and we went out together sometimes, he was brought up in Japan, you would never think so from his painting – but that may come.

To Theo van Gogh and Jo van Gogh-Bonger (letter 898)

Dear brother and sister,

Jo’s letter was really like a gospel for me, a deliverance from anguish which I was caused by the rather difficult and laborious hours for us all that I shared with you. It’s no small thing when all together we feel the daily bread in danger, no small thing when for other causes than that we also feel our existence to be fragile.

Once back here I too still felt very saddened, and had continued to feel the storm that threatens you also weighing upon me. What can be done – you see I usually try to be quite good-humoured, but my life, too, is attacked at the very root, my step also is faltering. I feared – not completely – but a little nonetheless – that I was a danger to you, living at your expense – but Jo’s letter clearly proves to me that you really feel that for my part I am working and suffering like you.

There – once back here I set to work again – the brush however almost falling from my hands and – knowing clearly what I wanted I’ve painted another three large canvases since then. They’re immense stretches of wheatfields under turbulent skies, and I made a point of trying to express sadness, extreme loneliness. You’ll see this soon, I hope – for I hope to bring them to you in Paris as soon as possible, since I’d almost believe that these canvases will tell you what I can’t say in words, what I consider healthy and fortifying about the countryside.

Now the third canvas is Daubigny’s garden, a painting I’d been thinking about ever since I’ve been here.

I hope with all my heart that the planned journey may provide you with a little distraction.

I often think of the little one, I believe that certainly it’s better to bring up children than to expend all one’s nervous energy in making paintings, but what can you do, I myself am now, at least I feel I am, too old to retrace my steps or to desire something else. This desire has left me, although the moral pain of it remains.

I very much regret not having seen Guillaumin again, but it pleases me that he’s seen my canvases.

If I’d waited for him I would probably have stayed to talk with him in such a way as to miss my train.

Wishing you luck and good heart and relative prosperity, please tell Mother and Sister sometime that I think of them very often, besides this morning I have a letter from them and will reply shortly.

Handshakes in thought.

Ever yours,

Vincent

My money won’t last me very long this time, as on my return I had to pay the baggage costs from Arles. I retain very good memories of this trip to Paris. A few months ago I little dared hope to see our friends again. I thought that Dutch lady had a great deal of talent.

Lautrec’s painting, portrait of a female musician, is quite astonishing, it moved me when I saw it.

To Theo van Gogh (letter 902)

My dear brother,

Thanks for your letter of today and for the 50-franc note it contained.

I’d perhaps like to write to you about many things, but first the desire has passed to such a degree, then I sense the pointlessness of it.

I hope that you’ll have found those gentlemen favourably disposed towards you.

As regards the state of peace in your household, I’m just as convinced of the possibility of preserving it as of the storms that threaten it.

I prefer not to forget the little French I know, and certainly wouldn’t see the point of delving deeper into the rights or wrongs in any discussions on one side or the other. It’s just that this wouldn’t interest me.

Things go quickly here – aren’t Dries, you and I a little more convinced of that, don’t we feel it a little more than those ladies? So much the better for them – but anyway, talking with rested minds, we can’t even count on that.

As for myself, I’m applying myself to my canvases with all my attention, I’m trying to do as well as certain painters whom I’ve liked and admired a great deal.

What seems to me on my return – is that the painters themselves are increasingly at bay.

Very well. But has the moment to make them understand the utility of a union not rather passed already? On the other hand a union, if it were formed, would go under if the rest went under. Then you’d perhaps tell me that dealers would unite for the Impressionists; that would be very fleeting. Anyway it seems to me that personal initiative remains ineffective, and having done the experiment, would one begin it again?

I noted with pleasure that the Gauguin from Brittany that I saw was very beautiful, and it seems to me that the others he’s done there must be too.

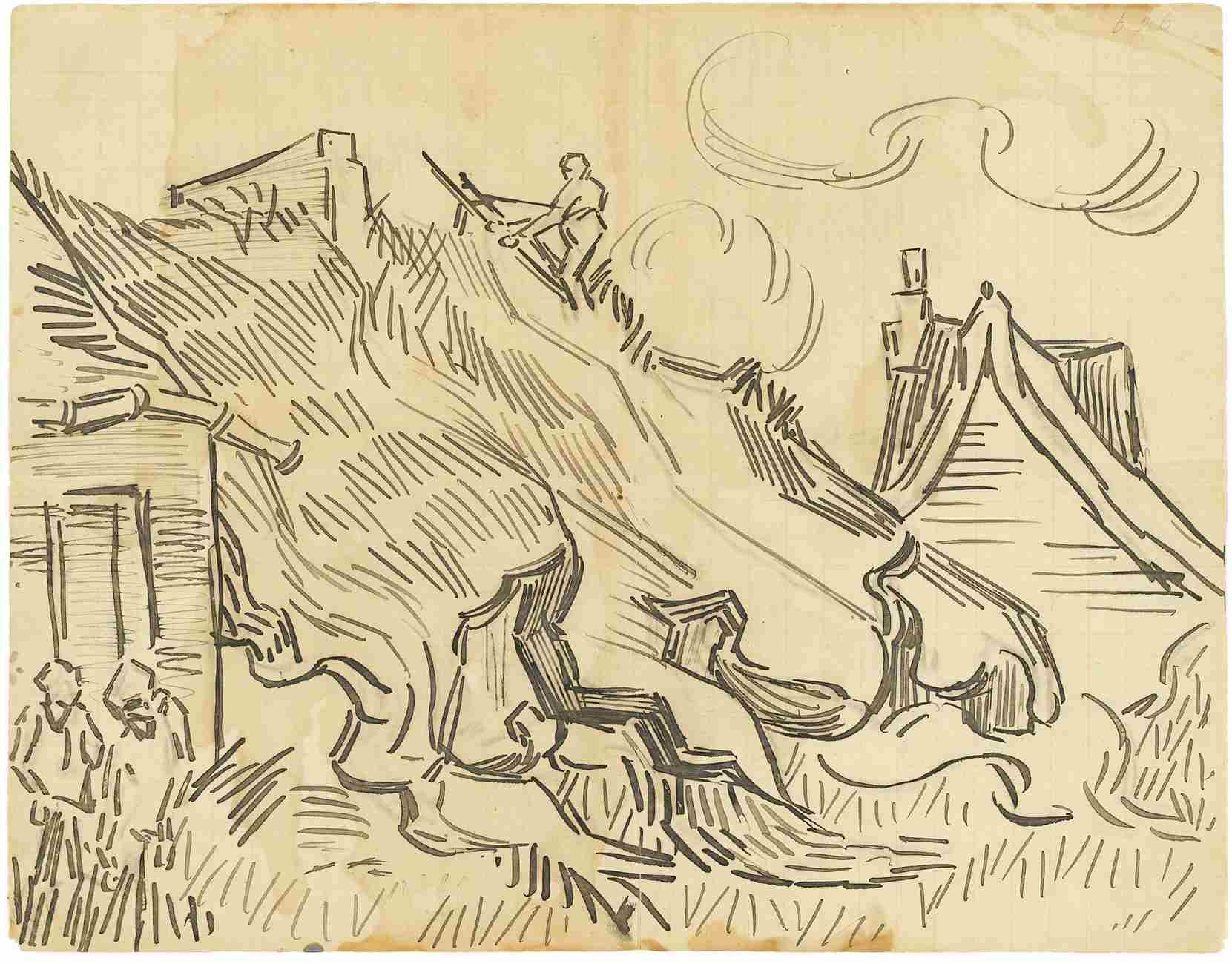

Perhaps you’ll see this croquis of Daubigny’s garden – it’s one of my most deliberate canvases – to it I’m adding a croquis of old thatched roofs and the croquis of 2 no. 30 canvases depicting immense stretches of wheat after the rain. Hirschig asked me to ask you please to order the attached list of colours for him from the same colourman you send me. Tasset can send them directly to him, cash on delivery, but then he would have to be given the 20%.

Which would be simplest.

Or you’d put them into the consignment of colours for me, adding the invoice or telling me how much they cost, and then he’d send you the money. Here one can’t find anything good in the way of colours.

I’ve simplified my own order to a very bare minimum.

Hirschig is beginning to understand a little, it has seemed to me, he’s done the portrait of the old schoolmaster, which he gave him, good – and then he has landscape studies which are a little like the Konings at your place as regards colour. It will become completely like that, perhaps, or like the things by Voerman that we saw together.

More soon. Look after yourself, and good luck in business &c. Warm regards to Jo, and handshakes in thought.

Yours truly,

Vincent.

[sketch A]

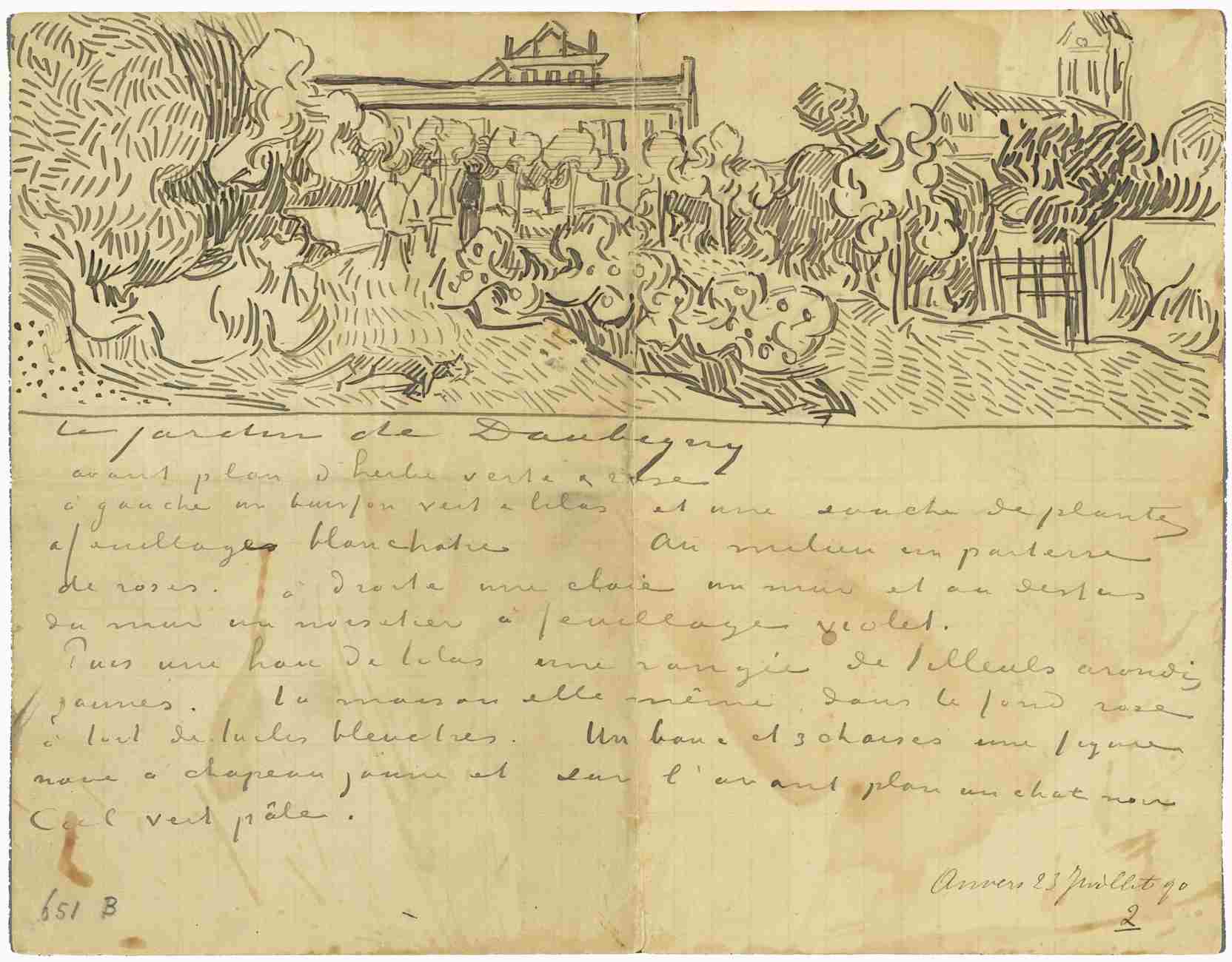

Daubigny’s garden

902A. Daubigny’s garden

Foreground of green and pink grass, on the left a green and lilac bush and a stem of plants with whitish foliage. In the middle a bed of roses. To the right a hurdle, a wall, and above the wall a hazel tree with violet foliage.

Then a hedge of lilac, a row of rounded yellow lime trees. The house itself in the background, pink with a roof of bluish tiles. A bench and 3 chairs, a dark figure with a yellow hat, and in the foreground a black cat. Sky pale green.

902B. Wheatfields

902C. Thatched cottages and figures

902D. Wheatfields