Creating a flower garden can be enormously satisfying, but there are many ways in which to give your blooms a second life. Whether they are destined for the vase or preserved for a whole lifetime, flowers can extend their attraction far beyond their place in the soil. Each feature in this chapter presents a different approach to getting the most out of our horticultural endeavours, be it an exuberant cut flower display, a revitalizing herbal beverage or even an entire business. However small your garden may be, reap the benefits of your blooms by adding an extra dimension.

This street is typical of the Parkdale district of Toronto in autumn. Long-lasting summer annuals flower through to October.

The streets are glowing with the rich colours of autumn as I drive through the Parkdale neighbourhood of suburban Toronto. Leaves of deep yellow, orange and red litter the pathways and there’s a chill in the October air. My arrival could not have been better timed for catching the famous Canadian fall, but despite the late season, the trees aren’t the only plants bringing colour to these residential avenues.

Sarah Nixon, a self-professed ‘flower farmer’, has spent 12 years transforming some of Toronto’s small suburban front gardens into places of floral abundance. Harvesting home-grown, organic flowers from her backyard, Sarah first began selling bouquets at produce markets. ‘I became obsessed,’ she tells me. ‘I needed more room to grow in the city, and when you look around you see so much unused yard space.’ So Sarah turned to nearby friends and neighbours. Given free rein to remodel and reshape a handful of gardens in which she could plant high-yielding flowers, she found her stock levels increased. The more flowers she was able to squeeze into a garden, the more spectacular it looked, and with a blooming portfolio of impressive front yards, it wasn’t long before Sarah built up the confidence to approach strangers also. ‘I say that I will plant tonnes of flowers and they won’t have to pay for anything nor lift a finger, not even to water the plants. They’ll get to enjoy the flowers without having to do anything.’ And in return for her labour, Sarah visits each garden three mornings a week with secateurs and a bucket.

The idea of using urban gardens to grow flowers on a large scale came to Sarah first as a response to the burgeoning global market for cut flowers. ‘When flowers have been flown in from places such as Ecuador and Holland, they’ve been packed dry for a week or so already, before they even reach the florist,’ she explains. ‘Whenever I buy flowers I notice such a difference in the energy. The flowers in my backyard are just so much more vibrant, diverse and irregular. Flowers that have been transported over long distances are usually very straight and all exactly the same, whereas my ones will have some curve and bend, which makes them so much more interesting to design with.’

High-yielding plants such as Cosmos bipinnatus (left) and Dahlia ‘Lakeview Peach Fuzz’ (top left) provide a regular crop for Sarah.

Together with Sarah I visited several of her flower gardens, all within a short distance of her house, and her floral workshop. Each garden offered different planting conditions, such as aspect, elevation, soil depth and access. In working with these varying factors Sarah is able to find the right growing environments for the right plants. While one garden may house a profusion of dahlias, another accommodates a lively combination of zinnias and foxgloves. Despite the differences, however, each of the front yards stands out proudly along the street, catching the sun in a kaleidoscope of colour.

Growing up on Vancouver Island, Sarah spent many of her summers working in an organic farm close to the family home. The resulting love of growing was what later drew her attention to an urban vegetable-growing scheme initiated by residents in the Saskatchewan city of Saskatoon. They were cultivating other people’s front yards and offering a portion of vegetables as payment for using the space, and Sarah adopted this method, applying it to cut flowers. ‘At the time no one else was really doing it,’ she says, ‘but there’s a growing appreciation for local flowers now, after the local food movement has become so popular.’

Sarah uses bamboo canes to stake dahlias. Producing a great wealth of orange pompom heads, this plant requires sturdy support.

Having developed her cut flower business under the name My Luscious Backyard, Sarah has expanded her retailing reach beyond local farmers’ markets. Toronto residents can purchase Sarah’s seasonal, low-mileage blooms in nearby florists and subscribe to weekly bouquet deliveries to the home or office. Sarah also offers flower arrangements for weddings and other events. ‘My gardens really get going in June with the growing season lasting roughly 19 weeks long. I deliver to five or six florists each week; I send out my availability list and they tell me what they want.’

Staying on top of one’s own garden is often demanding enough as it is, so keeping a high standard across ten gardens requires some careful planning. Sarah explains, ‘I used to plant things more like a garden garden, but then I realized that it was actually a lot more work for me in terms of weeding, watering, harvesting and just accounting for things.’ Sarah’s gardens therefore adopt a slightly more ‘orderly’ appearance, with flowers set out in productive lines, often leaving space to walk between plants. However, as Sarah’s gardens show, this doesn’t necessarily lead to mono-cropping. ‘I plant a lot of different things in the different gardens, which is nice for the owners, but it’s also helpful for me. Sometimes I’ll have pests such as earwigs or lily beetles in one garden, and in a garden a block away there’ll be none.’

Another advantage of growing for local florists and subscribers is the reduction of plant handling and transportation time. Sarah is able to trim, arrange and distribute flowers directly after harvesting them. ‘Everything leaves my house within 24 hours of being picked,’ she tells me, ‘so I’m able to grow many flowers that don’t ship well; you can’t ship cosmos, foxgloves or zinnias.’

While Sarah takes me around the gardens she pauses intermittently to greet and chat with passers-by, many of whom are local residents. It’s clear that Sarah’s presence in and out of the Parkdale flower beds is a familiar and valued one for those living in the neighbourhood. As they respond to her with smiles and appreciative comments, it’s easy to see how Sarah’s small-scale enterprise has benefited many more people than just the garden owners.

The Flower House’s exposed rear wall offered the setting for Lisa’s own installation. Displaying a mass of hanging delphiniums, her piece was inspired by Dior’s Parisian show.

Following the collapse of its principal industry and subsequent filing for bankruptcy in 2013, the once prosperous Motor City of the USA is a very different incarnation of its former landscape. As a result of a rapid fall in the population, many of Detroit’s suburban houses were boarded up and left to decay, their interiors becoming time capsules of an era left behind.

It was a pair of such houses that caught the eye of Detroit florist Lisa Waud. Purchasing the properties at auction for just $250, Lisa envisioned a plot of land in which she could cultivate flowers for her Detroit-based cut flower business. Known as ‘urban farming’, there has been a rise in this kind of property repurposing in one-time affluent cities, such as Detroit. Abandoned and decrepit houses are often worth less than the land on which they’re built, resulting in a wider potential for this type of small-scale real estate. Deciding to pay tribute to the former life of one of her newly acquired relics, Lisa delayed its demolition to put together a unique and ambitious project.

Teams of florists have come from all across the country to participate in this one-off event. Bright dahlias are woven into the fence surrounding the house.

On a chilly Michigan morning in the Detroit suburb of Hamtramck, I meet Lisa on the porch of the recently renamed Flower House. For one weekend only, florists from all over the country have filled the rooms of Lisa’s abandoned property with over 36,000 blooms. ‘The idea came to me three years ago,’ Lisa explains. ‘I saw images from the Dior show in Paris, where they constructed really beautiful flower-walls inside a mansion. The whole concept was about nature taking over, and that’s what happens here in Detroit in these houses with no one living in them.’

With the event taking place over just three days, the Flower House opens its doors for the first time in over a decade. Visitors to this most temporary of exhibitions are invited to explore the deteriorated rooms, each lovingly adorned with a mass of magnificent flowers. ‘To sit empty for 15 years and then have 2,000 people come through in 72 hours places quite a demand on the structural integrity of the house,’ Lisa tells me. ‘We put a lot of work into making it safe before any of the florists were let loose on the rooms.’ This is certainly reassuring to hear when walking around the frail framework of this extraordinarily decorated property. Weaving in and out of the tiny, dilapidated rooms, the enormous wealth of flowers both embellishes and sympathizes with the many household relics that have been left here untouched. For Lisa, the decision to leave these objects in place was an integral element of the project’s conception as they tell the story of the house as a home.

Lisa Ward sees her vision become a reality as the Flower House opens its doors.

In order to make the Flower House a reality, Lisa enlisted the help of her wide network of florists, offering individual teams the opportunity to develop their own floral schemes. ‘I feel that if you invite people into a project it’s no longer “mine” but “ours”,’ she explains. ‘I love how every room is different. Take the downstairs bathroom, for example; what they’ve done is very literal, it’s congenial with the setting. And then you come upstairs and there’s a tornado of flowers in the dining room.’

With the ground floor room exposed to the elements, the wall itself having collapsed, Lisa’s own installation subverts its ramshackle setting with a radiant profusion of blue delphiniums, hung from the ceiling. ‘It’s fall here right now,’ she says, looking up at the house, ‘so the natural colours are red, orange and yellow. I really wanted to stay away from those, to not be so seasonal.’ It’s hard to imagine that this wonderful creation will be pulled down in just two weeks time and the plot returned to soil. But the prospect of its second life is rather an exciting one. ‘I’ll be growing dahlias and peonies here,’ Lisa says, enthusiastically. ‘It’s going to be a flower farm.’

Sarah’s rustic planter is constructed with wood from a local reclamation yard.

When Sarah Collins decided to renovate the neglected back garden of her family home in Bristol, she saw an opportunity to give it a child-friendly makeover. Surfaced with uneven, cracked paving stones and weed-filled gravel, the somewhat dilapidated garden presented a hazardous environment for her two active young children.

‘When we bought the house a few years ago we inherited a backyard that was quite run down,’ Sarah says. ‘I wanted a fun, safe area for the kids to play in, as well as a bit of a sanctuary for me.’ Enlisting the help of friends and family, Sarah cleared away the broken stonework of the garden floor and replaced it with weed-suppressant fabric and a deep layer of bark chip. As she was keen to provide a space in which to grow a few plants, too, Sarah made room for a 2sq. m (21½sq. ft) raised bed. ‘Getting the balance right is often hard,’ says Sarah. ‘Theo and Annie love to run around, and I wanted them to have room to do so. But it was also important to me that there was a designated space for greenery too, somewhere full of life for us all to enjoy.’

Vivid stems of achillea and astilbe provide herbal and ornamental qualities. However, calendula is Theo’s favourite.

Initially intended as a little herb garden, Sarah’s raised bed provided somewhere to grow a handful of kitchen essentials, such as chives, marjoram and rosemary. However, as trips to a nearby park began sparking a curiosity in flowers for three-year-old Theo, Sarah decided to extend the use of her compact productive plot and have a go at growing some herself. ‘Both of the kids enjoy being around plants,’ she says. ‘They love all the different shapes and colours; they’re forever wanting to pick them!’ With such a confined area, Sarah was eager to include flowers offering more than their ornamental value. ‘I like plants that can be used in some way or another, as opposed to being simply cosmetic,’ she explains. ‘I’m a big fan of herbal teas. I’d read somewhere that many garden flowers could be used to make tea, and wanted to give that a try.’

As an easy-to-grow herbal favourite, camomile was an obvious choice for Sarah’s raised planter. Producing a high yield of bright yellow-and-white flower heads by midsummer, this aromatic herbaceous perennial is often quick to establish itself. ‘The camomile has already become a bit unruly!’ says Sarah, pinching a couple of the little daisy heads from a tall, dainty stem. ‘I divided the two original clumps this spring as they’d become too big for the space. I tend to cut the leaves back from time to time now, just to keep them in check.’

Herbal tea can be made using fresh or dried flower heads. Sarah deadheads her camomile plants, collecting the blooms and storing them in a jar (next image).

When it comes to harvesting her floral crop, the process couldn’t be simpler. ‘I just pick the flowers as and when they come out,’ Sarah says. ‘I keep a lock-jar to hand in the kitchen and just drop the heads in whenever I remember to.’ As the camomile flowers can be infused with water either dried or freshly picked, a supply of herbal stock can be easily amassed. ‘You only really need 2–3 flower heads to make a flavourful mug,’ says Sarah.

In addition to camomile, Sarah has made room for several other tea-producing flowers. Large yellow disks of pot marigold (Calendula officinalis) are coupled with the tall, nodding heads of Achillea millefolium, both of which are believed to contain restorative properties. ‘I’m not too experimental with my herbal flowers,’ Sarah tells me, ‘and they’re really only an extension of the flower bed itself. But it is nice to have an active involvement with the plants in our garden; a little connection to the wider natural world.’

Growing and harvesting your own herbal teas can be enormously rewarding. Nothing beats a home-grown brew, especially with the convenience of a supply so close to hand. So why not go that extra step and create ready-to-use tea bags from your floral yield? You can also treat them as charming handmade presents for friends.

Of the many plants that offer a delicious herbal infusion, camomile is one of the easiest to grow. The familiar, daisy-shaped flower heads begin forming from late spring and can then be picked and dried to preserve their sweet, meadow-rich flavour. Spread them out on a sheet of paper to dry out or alternatively dry them on the stem, suspended by string in a cool, airy environment.

Camomile is just one of many flowers with which you can make a flavourful tea. Why not try others? Fennel, calendula and echinacea all offer unique flavour characteristics along with their individual herbal qualities. Available from most garden centres and nurseries, all three are well suited to being grown in pots and containers. It is essential that plants are correctly identified before ingesting them, as well as any potential allergens.

1. To make your camomile tea bags you’ll need coffee filters, scissors, string, coloured card, a stapler and your dried camomile flowers.

2. Fill a coffee filter with 4–5 dried camomile flowers.

3. Fold the top of the filter down over itself.

4. Fold one side in to make a right angle at the bottom.

5. Now fold the other side in so that the filter forms a rectangle.

6. Cut a 10cm (4in) length of string with a knot at one end.

7. Staple the string to the coffee filter, just above the knot. This will fix the folds in place.

8. Cut a rectangle of coloured card then fold and staple it, forming a tea-bag tab.

When garden space is in short supply or absent altogether, bringing flowers into the home sometimes requires a little creative thinking. For Clemmie Power, a life-long pastime has provided an ornate alternative to a garden of her own.

‘I can remember pressing flowers as a child,’ says Clemmie. ‘My grandparents live in America and I went over there for a family wedding. As a flower girl I was given a bouquet of small white roses and greenery. My grandparents had also given me a flower press, so when I got home I pressed all of my bouquet.’ And so began a hobby which has continued into adulthood.

‘A friend made me a flower press as a present last year,’ says Clemmie. ‘It’s made from olive ash wood, which is really tough and heavy. The flowers don’t stand a chance!’ Layered with cardboard dividers, this sturdy implement allows Clemmie to press a large number of flowers at the same time. Typically left to dry out for 3–4 weeks, her flowers are then either stored in notebooks or arranged in picture frames to act as gifts. ‘It was only recently that I decided to try out a flower mobile,’ says Clemmie. ‘I wanted a way to create a more interactive display, something three-dimensional, to get the most out of the pressings.’ Lightly strung with sewing thread, Clemmie’s flowers are suspended from her hall ceiling, where they make a miniature indoor garden apparently floating below a woven wood wreath.

Clemmie splays the stems of Astrantia major on fresh paper before returning them to the flower press.

Yellow freesias and white nigella flowers hang from the woven hazel mobile, suspended in the hallway.

‘The idea behind the mobile was to allow light to shine through the flowers,’ explains Clemmie. ‘Pressed flowers look lovely on paper, but there are intricate details within the petals which are only revealed when they are backlit.’ When the delicate floral arrangement is viewed from below, many new elements are exhibited, from complex capillary structures to individual patterns of coloration. And with the flowers weighing so little, they turn on the slightest movement of air, mirroring the natural motion of plants, when caught by the breeze.

Clemmie deliberately kept her display simple. ‘It was tempting to add more, but I needed to restrain the arrangement,’ she says. ‘The mobile looks best with just a handful of flowers; they need to be able to move freely without touching one another.’ Refining her pressed palette, Clemmie mixed bright yellow freesias with dusky maroon astrantia. In addition, flattened nigella heads float at the top of the structure, like little moons. For an elegant effect, she used long stems for the mobile so that the flowers would display well, while the base of the mobile was made with twisted hazel stems, woven together to form a circle. ‘I used hazel cut from a friend’s garden,’ says Clemmie. ‘They have a wonderful copse which throws up these straight, malleable rods.’ Nest-like in its formation, the base offers an ideal framework from which to thread the flowers.

When it comes to the process itself, pressing flowers is not without its challenges. ‘It’s very much trial and error,’ Clemmie says. ‘When you open up the press the results can often be disappointing.’ Some flowers are unavoidably tricky to press. ‘Cornflowers are one of my favourite flowers because of their electric blue. Frustratingly, though, they fade very quickly to a pale pink or white.’ Another factor to consider once the flowers have begun pressing is that of moisture; the act of pressing removes liquid from the flowers, and the paper surrounding them soaks it up. Therefore Clemmie must check on her flowers once a week, replacing the paper each time to ensure that they do not become mouldy.

Clemmie’s heavy-duty press produces an array of colourful blooms. Those not used for framing or a mobile are decoratively preserved on cartridge paper.

Beyond the attraction of its natural beauty, a flower can often carry a personal significance that makes it something to treasure in the long term. While a cut flower in a vase will inevitably shrivel and fade, a pressed flower will stand the test of time. With this simple yet traditional press, you can set about retaining both the vibrance of the flower and the sentiment that lies within it.

Once your flowers are pressed, there are various ways to present, catalogue and display them. Collecting them in a notebook with accompanying information such as the date, species and location where they were picked can be a satisfying process. Alternatively, framing flowers as simple single specimens or as a collage can be a rewarding way to preserve and exhibit your pressings.

One of the aims in pressing flowers is to remove moisture from the stem and petals so that they do not rot. As the flowers are squeezed and flattened their moisture is absorbed by the paper, so it is best to replace it once a week to keep it fresh and able to soak up any further dampness.

If you find that there isn’t enough room in the flower press for the amount of material you wish to preserve, you can use longer bolts and additional layers of cardboard. The cardboard dividers will prevent flowers being pressed on top of each other, which would lead to markings on the petals.

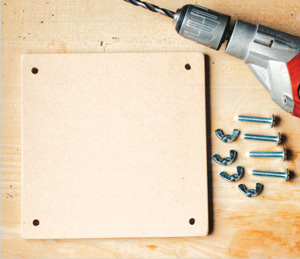

1. Using a handsaw, cut two matching pieces of 10mm (⅖in) thick MDF board to 220 x 220mm (8¾ x 8¾in). Alternatively, a timber yard or DIY store may cut them for you. Sand down the edges to a smooth curve.

2. To connect the pieces of MDF you’ll need four M8 size bolts with accompanying wing nuts. Using an 8.5mm or 9mm drill bit, drill a hole right through both blocks at each corner.

3. Check the hole alignment by pushing the bolts through both pieces of MDF and fastening the wing nuts.

4. Using a ruler, measure out two identical squares of ordinary cardboard, ensuring that they fit within the margin of the holes. These will act as cushions between the MDF and flowers being pressed.

5. Cut out a rectangle of craft paper that, once folded, has the same dimensions as the cardboard in the previous step. Trim your flowers and attach them to this paper, using thin strips of masking tape.

6. Fold the paper over the flowers and sandwich it between the two squares of card inside the press. The press can now be screwed down tightly. It may be helpful to attach a note detailing the flowers inside.