Sometimes even the tiniest of garden plots can serve a whole host of different purposes. The process of growing flowers can be an invigorating experience, and the resulting blooms an unparalleled reward. However, the gardeners in this final chapter have sought to create gardens with an additional motivation, offering inventive solutions to a growing concern. With the number of bees now declining on a global scale, the plight of our pollinators is making headline news – and bad news for the bees means bad news for many of our most-loved flowers, not to mention food crops. Even the smallest of domestic gardens now has the opportunity to play a key role in reversing this decline.

Providing year-round forage for bees is at the heart of Dr Luke Dixon’s project.

We’ve all been there, standing on a monochrome platform, counting down the minutes until our train arrives. However, with the recent arrival of the Bee Friendly Trust’s colourful conservation planters, a handful of London’s railway stations now offer commuters a productive and engaging way to pass the time.

Set up in 2015 by professional bee keeper Dr Luke Dixon, the Bee Friendly Trust aims to support the dwindling population of honey bees both locally and across the world by raising awareness through planting and educational schemes. ‘Putney was our first station,’ Dixon tells me. ‘The station platforms were looking a little forlorn and we thought planters would brighten up the platforms for commuters while at the same time providing forage for bees.’

With Putney Station’s flower-packed beds proving an enormous success, Dr Dixon’s team began extending the reaches of their wildlife-nurturing scheme. Working in conjunction with South West Trains, Bee Friendly erected flower planters further down the tracks. ‘We began linking up stations to create pollinator corridors around London,’ he says. ‘The removal of suitable plants to forage on has been a major factor in the recent decline of the honey bee. Creating corridors of forage has the potential to make a significant contribution to the survival of bees in urban areas.’

Rather uncharacteristically for municipal garden planters, green-fingered commuters are also encouraged to help with their upkeep. ‘We want people waiting for their trains to help look after the planters,’ says Dr Dixon. With simple tasks, such as deadheading and weeding, commuters can have an active involvement, which in turn offers a sense of shared ownership. ‘It really helps with the look of the planters, and we’ve been delighted with the response. It doesn’t always work; some people take the ownership too far and we do have plants stolen. But we also find others planted, so there’s a balance.’

Another contributing factor to the planters’ success is the plants that have been selected. Those favoured by bees tend to differ a little from the typical plants within council-planned schemes. Dr Dixon explains, ‘Honey bees see a different colour spectrum to humans. They don’t see red but they do see ultra-violet, and even colours we have no names for. So bees particularly love flowers at the purple and violet end of the spectrum.’ Anyone growing lavender on a bright summer’s day will certainly testify to this; with flower heads often drooping under the weight of numerous bees, it’s a clear favourite. Buddleia, lilac, and rosemary are equally popular.

The frequent use of infertile plants is also a concern for the Bee Friendly Trust. ‘So much of our urban ornamental planting is made up of sterile flowers, which are of no use to insects at all,’ says Dr Dixon. With this in mind, the Trust has sought to feature some less conventional inclusions that are more likely to be found adorning a wild hedgerow or hillside than a city planter. Standing by one of Putney station’s flower beds, I notice a clump of pink thrift (Armeria maritima), its bright, clustered flowers pushing up through the compost. I can’t resist the urge to deadhead the dulled, finished stems as I would in my own garden. It feels both wonderfully satisfying and yet strangely against the rules.

Nectar-rich flowers have been selected for use in the station planters. Key plants include geranium (top left), foxglove (far right) and allium (bottom left).

Alan’s truck sits proudly at the entrance to Cleeve Nursery on the outskirts of Bristol.

‘People are astounded,’ nurseryman Alan Down says enthusiastically, ‘they get their phones out straight away.’ Walking me around his four-wheeled flower bed, he describes the reactions from people encountering his ‘pickup pollinator’ for the first time. ‘They just love to see fun in the garden. Hopefully they also come away with the message that we have an opportunity to do much more for bees in our own gardens.’

Originally conceived as an eye-catching and educational display for the Chelsea Fringe Festival, Alan’s truck garden now adorns the entrance to his plant nursery on the outskirts of Bristol. Held in conjunction with the RHS Chelsea Flower Show in London, the Chelsea Fringe celebrates the alternative side of gardening. ‘I was actually looking to plant up an old Morris Minor for the festival, or an Indian rickshaw!’ Alan says. With the high demand for repurposing these kinds of vehicle, he decided instead to go with a pickup truck on offer at a local scrap metal dealer: ‘Strangely, he’d had the same idea, so he helped to remove the engine and strip down the pickup.’

Blue aster (Felicia amelloides ‘Santa Anita’), white argyranthemum and yellow monkey flower (Mimulus guttatus) produce a dense mat of flowers within the pickup planting.

The truck provides a range of planting environments, from deep soil in the pickup bed to arid conditions below the bonnet.

Alan believes that there’s an opportunity for residential gardens to significantly bolster the number of bees.

Tall spires of globe thistle (far left) rise above Alan’s pickup – a plant almost as irresistible to bees as Salvia nemorosa (below right).

With flowers spilling abundantly from every feature of the truck, there’s a wonderful sense of playfulness. Beneath the raised bonnet spring wallflowers and chives; sacks of bedding plants are suspended along the chassis, and there’s even a scarecrow at the wheel. However, behind the lively, whimsical nature of Alan’s Pickup Pollinator there’s a message that lies very close to his heart. ‘With the rise in monoculture farming and the consequential lack of wild flowers, the countryside is becoming ever more commercialized,’ he tells me. ‘I have sympathy with the farmers. They’re being squeezed by low prices and a global food market, and are therefore having to be as efficient as possible; but there’s less and less room for wildlife.’

On a more positive note, Alan has also noticed a shift in the type of plants that now interest residential gardeners. With bee- and butterfly-friendly plants becoming increasingly popular, he’s seen a definite move towards a more supportive interaction with nature. ‘As a plant nursery we have a role to play in encouraging people to provide for wildlife in their own gardens,’ he says. ‘As bees are coming under threat, we’re trying to promote our message as much as we can.’

Combining his nurseryman’s knowledge and enthusiasm for wildlife, Alan has designed his pickup-planting around attracting the greatest volume of insects and pollinators possible. Comprising annuals, perennials, shrubs and bulbs, the little truck garden offers a wide and varied source of nectar-rich flowers. From the clustered whites of Cotoneaster salicifolius to the tall purple spires of Salvia nemorosa, bees and hoverflies are drawn in by a magnificent array of colour. ‘What we’ve tried to do is to have successional flowers,’ Alan explains. ‘The early bees that emerge after winter need just as much pollen and nectar as those which come out in summer.’ Therefore, by providing a steady flow of sequential blooms, the pickup can offer a food supply for the majority of the year.

Lifting the thick foliage at the back of the truck, Alan points out an alpine strawberry. ‘Those have been pollinated by the bees,’ he says. ‘There’s a huge amount of variety here. As soon as a gap appears we’ll put something new in.’ The pickup pollinator also offers a variety of growing conditions. With the bonnet raised and obstructing rainfall, the engine section is particularly dry, dictating the kinds of plants used. Sedum spectabile, chive alliums and wallflowers all thrive in this less irrigated environment. Conversely, the back of the truck is filled with approximately 45cm (18in) of soil, providing a much deeper and more saturated growing medium. Almost bursting at the seams, this section contributes some of the damp-favouring meadow species such as comfrey, nasturtium and the Spanish daisy, Erigeron karvinskianus. The cab of the pickup truck even acts as a miniature greenhouse, a climate Alan has made the most of with the inclusion of tomato plants; not an inch of his truck has been wasted in his search to help the bees.

There can’t be many people as well versed in constructing peculiarly placed gardens as Dusty Gedge. As a green infrastructure consultant, Dusty’s speciality is roof gardens, and with an impressive high-rise record he’s never shied away from a new challenge.

Invited to consider the ageing roof of one of central London’s most cherished museums, Dusty stumbled upon an opportunity to experiment with an idea he had long been wanting to try. Guiding me along a walkway at the top of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, he says, ‘I found a series of roofs each encompassing two slopes leading down to a flat surface. Rain water running off the slopes collects in a central gully, which is about 15cm (6in) deep. By damming the run-off exit, I could have rain water sitting in that gully, replicating a wetland environment.’

Hidden within the enormous expanse of the V&A’s rooftop, Dusty’s wetland occupies an area of about 8sq. m (86sq. ft), forming the most unexpected oasis one could imagine. Rounding the right-hand slope, I’m met with a familiar host of flowers in the most unfamiliar setting. Riverside regulars, such as purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), ragged robin (Lychnis flos-cuculi), and water forget-me-not (Myosotis scorpioides) weave among sedge grass and pebbles. There are damp-loving species, such as cuckoo flower (Cardamine pratensis) and water mint (Mentha aquatica), which one might encounter along the fringes of a natural pond. The planting is so lush that it takes a moment before the water is visible, reflecting the ox-eye daisies (Leucanthemum vulgare) and buttercups (Ranunculus acris).

Dusty Gedge with V&A volunteer Rena Melnyczuk beside the water-meadow.

Dusty’s wetland has created a resource for the V&A’s beehives.

‘I had always wanted to make a wetland roof for nature,’ Dusty tells me, stepping carefully through the dense planting. ‘Most of my roofs are dry grassland, so this was a completely different situation.’ And ‘different’ is certainly the word. I ask Dusty how he set about orchestrating such a precarious and adventurous project; surely the potential of an overflowing roof was a little unnerving? ‘When it rains the garden takes on a lot of water,’ he says. ‘If it leaked it wasn’t going to leak into a house, it was going to leak onto very, very precious objects.’ Bringing in an experienced green roof contractor, Active Ecology, Dusty’s team set about designing and constructing a system that would make sure the museum remained safe and dry. ‘Once the water level reaches a certain depth it triggers a weir, which then lets excess water out into the drain.’ In this way, harvested rainwater is repurposed as a resource for nature, while at the same time never accumulating to the extent of posing a risk to the roof.

The predominantly native planting includes water forget-me-not (Myosotis scorpioides) and ragged robin (Lychnis flos-cuculi).

As president of the EFB (European Federation of Green Roof Associations), Dusty has placed nature at the very heart of his waterlogged creation, making the V&A’s wetland garden the epitome of successful green infrastructure. Bumble bees, dragonflies, hoverflies and even water snails have all found their way up onto the roof, the last of which came as an additional surprise. ‘They just turned up!’ exclaims Dusty. ‘The nearest pond is probably in Kensington Gardens. One theory is that they were brought here on the feet of a visiting heron.’ The garden has provided a refuge for a wide range of creatures, like a kind of high-rise watering hole for transitory wildlife. ‘The idea was that it would become self-maintained,’ says Dusty. ‘I like seeing a few dead stems. Solitary bees will very often over-winter in tall ones, so we’ll try to leave them at least until April or May when the bees are likely to have left.’

Alongside its influx of natural newcomers, the wetland planting also serves the museum’s resident bee hives, which is how V&A volunteer Rena Melnyczuk came to be engaged with the garden. ‘As a gardener I kept looking at it and thinking “I’m not sure that looks right!”’ she tells me. ‘In my own garden there are lots of things I would have pulled up by that time. I hadn’t fully appreciated that it just had to grow naturally.’ It didn’t take long before Rena’s interpretation of the space began to shift. Seeing the space develop, she soon fell in love with it. ‘It’s very peaceful. At about 11 o’clock in the morning, with no one else up here, it’s something very special. I’ve ended up planting a lot of the same plants in my own garden now!’

‘We’re trying to demonstrate that you don’t have to make roof gardens formal – you can make natural prairies,’ says Dusty. ‘This roof told us what we could do. The garden has been designed to fit this situation; we haven’t imposed anything on it, which I think is kind of cool.’

Bearing a profusion of scented flower heads, Lavandula angustifolia ‘Grosso’ makes for an ideal balcony bouquet.

Where growing space really is in short supply, choosing the right flowers can be a tough decision, for when they fill what little room is available the selected plants are required to offer far more than just their summer blooms. Dressing the window of her rooftop apartment in Paris, Lucy Davies was faced with just this dilemma.

‘I think everybody starts out with high expectations for their window boxes,’ Lucy says with a smile. ‘There’s so much pressure on that one small plot, especially when it’s the only bit of garden you have!’ With its narrow yet sun-soaked window ledge, Lucy’s modest but stylish apartment sits at the top of a residential block in the heart of the French capital. Like many inner-city apartments of its kind, it has a wooden-clad window railing and this provides the support for Lucy’s hanging planter. ‘I wanted something simple for that confined space, elegant yet versatile,’ she explains.‘It can be wonderful just putting one kind of plant on a site and watching it do its thing.’

It wasn’t until a trip to Pas de Calais in Northern France that Lucy found the inspiration for her compact little window garden. ‘I was visiting a friend along the coast and encountered the most spectacular lavender shrubs I’d ever seen. It was an unseasonably warm, early summer evening and the scent of the flowers was just incredible.’ Enchanted with the sheer mass of delicate blue flowers and their intoxicating aroma, Lucy was drawn to the striking shrubs. However, there was an additional element which affirmed that lavender was the plant for Lucy. ‘I couldn’t believe how many bees there were,’ she says. ‘The flower heads were smothered in them, which really brought the plants to life’. Passionate about nature and the importance of bees, Lucy was excited to bring a little of this rural spectacle into her high-rise home.

At the end of the summer, once the bees have had their fill, Lucy cuts back the stems and ties them into bunches.

Positioned in full sun and lined with hessian, Lucy’s planter provides the kind of conditions that lavender tends to thrive in. ‘I’m amazed how happy the plants have been,’ says Lucy. ‘I read that although lavender requires regular watering, it hates sitting in damp soil, so the hessian is there to help prevent the roots from becoming saturated.’ Opting for one of the more reliable, showy forms, Lucy picked out Lavandula angustifolia ‘Grosso’ at a local garden centre. ‘This variety was apparently grown for its particularly long stems and strong scent, so it was perfect for the apartment,’ she says. ‘I bought two of them; it’s amazing how quickly they’ve filled the container.’

When it comes to the provision of nectar for foraging city bees, lavender flowers perform a crucial role. With a natural slump in available garden blooms between June and July, they fill the gap at a critical time for developing hives. Says Lucy, ‘Honey being produced here by urban bee keepers is of just as high a standard as in the countryside. So it’s great to be growing a plant which in a small way contributes forage for some of Paris’s bees.’ By pruning back the spent flowers in one cut each year, the plants can be kept compact, leaving their silvery foliage as interest throughout the winter. The by-product of this is the resulting bounty of aromatic cut stems. ‘I keep all of the cuttings and hang them in bunches to dry out,’ says Lucy. ‘It’s wonderful to cook with, and occasionally I make small aromatic pouches, either to go under the pillow or as gifts for friends.’

Typically, lavender is pruned back once a year, leaving you with a bounty of fresh, heavily scented stems that can be put to many different uses. For example, they can be pressed to release a fragrant oil, made into tea and even rubbed on the skin as an insect repellent. Probably the most rewarding way to take advantage of a plant with such a long-lasting aroma, though, is to make a lavender bag. Hung with clothes, nestled in the sock drawer or even placed under your pillow, it is a great way to bring the freshness of the summer into your home.

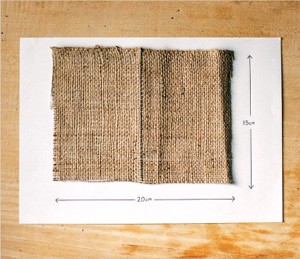

1. You will need hessian fabric, scissors, a ruler, a pen, a large needle, thick thread, ribbon and lavender prunings.

2. Taking your hessian and ruler, measure out and cut a rectangle sized 15 x 20cm (6 x 8in). Draw a line exactly down the centre with a marker pen.

3. Fold the hessian rectangle in half. Sew together the long edge and one of the two shorter edges. This will leave you with a pouch which is open at the top.

4. Turn the hessian pouch inside out, then fill it nearly to the top with your dried lavender heads, removed from their stalks.

5. Holding the bag at the top, pinch in the sides and tie tightly with ribbon.