Statistical Appendix

The population on which I based most of my calculations comprised just under 2,700 men who held local office in the Pan-German League between 1891 and 1914. Most of them I identified in the reports submitted by the chapters for publication in the League’s journal. These reports I supplemented with rosters of local leaders which appeared in the Pan-German League’s handbooks for the years 1899, 1901, 1905, 1908, and 1915 (the last volume did not yet reflect the dislocation of the war).1 From all this data I was able first to draw conclusions about the activity of these men in the organization – how long they were active and the offices they held in the chapters. More significantly, these reports and rosters provided information about the kinds of people who were active in the chapters, for the Pan-Germans diligently observed the common practice of listing themselves by occupational labels. From these labels I was able to make inferences about levels of their education. I could also estimate which of the local leaders were noble or retired.

The idea of using this kind of information is not new. Mildred Wertheimer was the first to do it, and her findings have informed the conclusions of most subsequent historians of the Pan-German League. I went beyond her work in two respects. In the first place, my population was many times the size of hers, for she did not use the reports from the chapters in compiling her data. In the second place, I broke this information down into different analytical categories. From Wertheimer’s own categories I found it difficult to know precisely what she was trying to measure. Her categories included ‘teaching profession’, ‘businessmen’, lawyers’, ‘physicians’, ‘nobility’, ‘Reichstag deputies’, and several others.2 Some of these categories, such as ‘lawyers’, described reasonably coherent social groups, bound by common background, training, and professional experience. Others, such as ‘teaching profession’, which presumably comprehended everyone from Volksschullehrer to Ordinarius, were so broad that they obscured crucial differences in background, training, and professional experience.

The deficiencies in Wertheimer’s categories pointed to an underlying problem, a failure to distinguish between categories that relate to economic position and function and those that relate to social status – between class structure and hierarchy of status and prestige.3 The one set of categories describes objective roles within an economic system; the other describes a social and cultural system structured not only by economic function and position, but by birth, education, tradition, and by other conventions and perceptions for which objective grounding may be largely lacking.

I attempted to account for this distinction by constructing two separate sets of occupational classifications, one for economic position and function and another for social status. The first presented comparatively few problems. The categories I used were those of the contemporary German census (see Tables 5.2, 5.7).4 I did encounter several difficulties, chiefly the notorious and conscious ambiguity of the census-taker’s rubric ‘(3.) Independents, top-level officials and employees’, a label which grouped peasants and master artisans together with the wealthiest and most powerful men in the country. I was also compelled to adjust some of the subcategories of economic function to fit my own needs. My rubric ‘(B 9.) Industry: other or unclear’ included a large number of men who listed their occupations only as ‘Fabrikant’, ‘Fabrikdirektor’, or ‘Industrieller’.Into the category of ‘(F.) Others’ I placed students and the men who described themselves as ‘Rentier’, ‘Rentner’, or ‘Privatier’, as well as the four women who turned up in the membership.

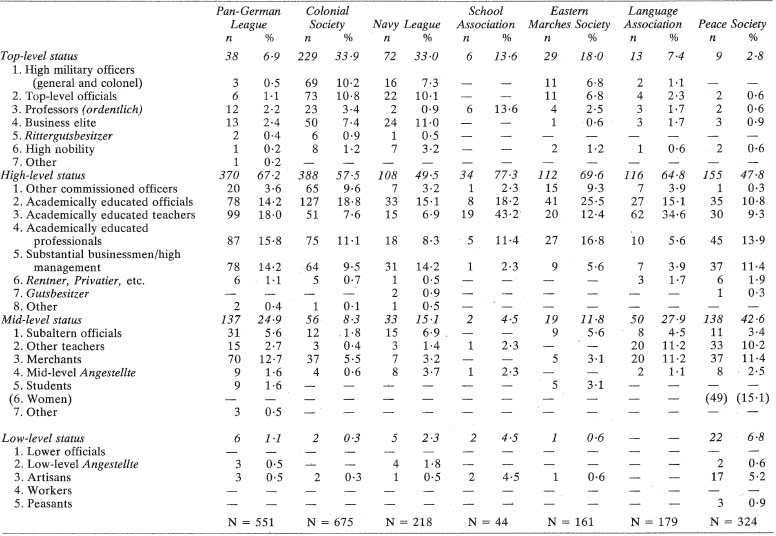

It was more difficult to construct a set of categories to describe and measure social status (see Table 5.8). Because status rests to such a large extent upon subjective perceptions and other factors not easily measured, the undertaking impressed me as risky, but the importance of status as an explanation for the Pan-German League’s behavior convinced me that the risks had to be run, even if the conclusions that emerged were shaky. I searched widely for models I might use for a social-status scale. I found helpful schemes in the contemporary literature, for the patriots were themselves interested in ways to group their membership lists according to social position.5 I examined models devised by historians and sociologists.6 Finally, I consulted several of my colleagues whose judgment I value.

The product of these labors was a social-status scale which reflected the various sources I consulted but was ultimately my own. I settled on a four-tiered model, which could accommodate distinctions based not only upon occupation, but upon wealth, education, and Stand. The four tiers were:

(1) Low-level status: included peasants, artisans, low-level employees (Angestellte), and manual workers.

(2) Mid-level status: included public employees and teachers without an academic education, mid-level Angestellte, and most people who described themselves as Kaufmann.

(3) High-level status: included public officials, teachers, and professionals with an academic education, military officers below the rank of colonel, and substantial businessmen and managers.

(4) Top-level status: included high military officers, top-ranking public officials, the commercial and industrial elite, high nobles, and ordentliche professors.

Assigning people to the tiers involved some compromises which struck me as arbitrary – as well as considerable guess-work. The main problems were the ambiguous designations ‘Kaufmann’ and ‘Fabrikant’. Unless I had additional evidence that suggested otherwise (as I did in the cases of some of the Hamburg merchants), I consistently placed people who called themselves Kaufmann in the ‘mid-level’ tier and the ‘Fabrikanten’ (some of whom were doubtless artisans) in the ‘high-level’ tier as ‘substantial businessmen’.7 It must remain only a hope that this consistency might have neutralized some of the anomalies.

For all its problems, the social-status scale did prove useful. By assigning a numerical value to each of the tiers, I could calculate a figure for ‘mean social status’ as an index of the relative weight of the tiers within the organization. This index in turn enabled me to make comparisons between the Pan-German League and other organizations, as well as comparisons among sectors of the Pan-German League itself.

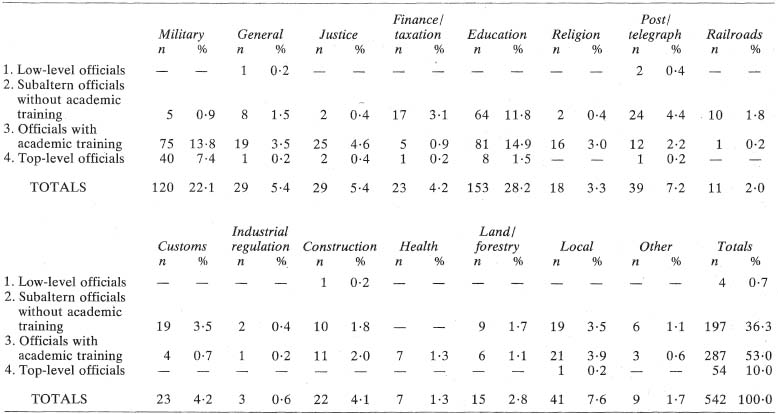

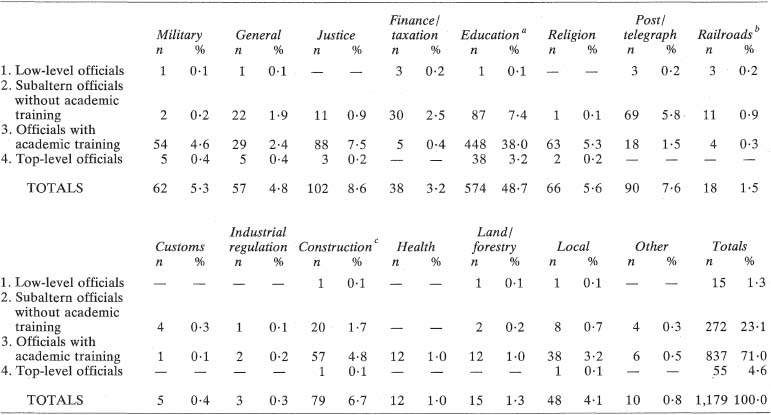

Because a large segment of my population was publicly employed, I constructed a scale similar to the social-status scale for public administrative position. Again I used a four-tiered model:

(1) Low-level officials (of which there were extremely few).

(2) Subaltern officials without an academic education.

(3) Officials with an academic education.

(4) Top-level officials.

I assigned people to these tiers with more confidence than I did in the social-status scale, because administrative titles were generally more precise and because the educational qualifications for administrative positions were generally more clear. Academic education was the criterion for distinguishing between the second and third tiers. The difference between the third and fourth tiers, between high- and top-level officials, was more difficult to define. I normally resorted to a scale of salaries and placed all the men in the top level whose offices carried salaries in excess of ten thousand Marks on the Prussian scale of 1897.8 Assigning numerical values to each of the tiers then enabled me to calculate, again for purposes of comparison, an index of ‘mean public administrative position’.

The initial sorts and calculations for the population resulted in Tables 5.1, 5.2, 5.3.

I found additional information on a subpopulation of Pan-Germans who held national office in the organization – in the executive committee, whose membership lists I compiled for the entire period 1891–1914, and in the much larger national board of directors, whose membership list I examined only for the year 1899. Biographical dictionaries and other sources produced information about the years of birth and experiences abroad of a substantial number of these people. This information appears in Tables 5.4 and 5.5.

In order to compare the social composition of the Pan-German League’s local leadership with that of leaders of other patriotic societies, I selected twenty-five communities in which chapters of the League existed alongside chapters of one or more of the other organizations. I chose these communities in order to provide as broad as possible a variation in size, economic complexion, and geographical distribution. Most of the communities were necessarily large, however, for smaller towns normally did not play host to several patriotic societies. The selection was further limited by the paucity of chapters of the Pan-German League in the east and the paucity of chapters of the Eastern Marches Society in the west. The statistics I compiled thus probably understated the weight of agricultural occupations in the patriotic societies, although the distortion was doubtless not extreme, for with the exception of the Eastern Marches Society, none of these organizations was strong in the rural eastern parts of Germany. The communities I selected for study were Barmen, Berlin, Breslau, Cologne, Darmstadt, Dresden, Düsseldorf, Erfurt, Eisleben, Eisenach, Essen, Gotha, Hamburg, Halle, Hanover, Heppenheim, Karlsruhe, Kassel, Leipzig, Munich, Moers, Plauen, Pirna, Potsdam, and Stuttgart. From the reports which the chapters published in their societies’ journals or from handbooks, I gathered information about the local leaders of the Geman Colonial Society,9 the German Navy League,10 the General German School Association (for which the information was very sparse),11 the Eastern Marches Society,12 and the General German Language Association.13 For the comparison I sorted out the figures on the local leadership of the Pan-German League in the same twenty-five communities. I also compared the figures for the patriotic societies with those of the German Peace Society.14 Given the concentration of the Peace Society’s chapters in the southwest, however, a comparison based only on the twenty-five communities was impossible. Accordingly, the figures on the Peace Society’s local leadership represented all the names I could identify throughout the country. The comparisons among all these organizations are in Tables 5.6, 5.7, and 5.8.

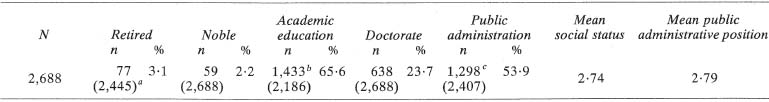

Table 5.1 Characteristics of Local Leaders of the Pan-German League

a This is the figure on which the percentage is calculated. It is N–MV

b Judging from occupation, this figure is distributed in the following manner:

| n | Pct | |

| University | 1,094 | 87.4 |

| Technische Hochschule | 139 | 11.1 |

| Agricultural or forestry academy | 15 | 1.2 |

| Artistic Academy | 3 | 0.2 |

| Other or unclear | 182 | – |

c This figure includes parliamentarians and those people whose positions were ‘beamtenähnlich’: Kommerzienrat, Medizinal- or Sanitätsrat, Justizrat.

Table 5.2 Economic Positions and Functions of Local Leaders of the Pan-German League

a Students

b Rentner, Rentier, Privatier

c This figure indicates the degree to which these economic functions were over- or under-represented in the Pan-German League. To calculate it, I divided the percentage of the Pan-German League’s local leadership in each of the six economic functions by the percentage of all male Ewerbstätige in each of the functions in 1907. If the index exceeds 1.0 the function was over-represented: Kaiserliches Statistisches Amt, Statistisches Jahrbuch für das Deutsche Reich 1913 (Berlin, 1913), pp. 16–17; cf. Kaelble, ‘Chancenungleichheit’, pp. 128–9.

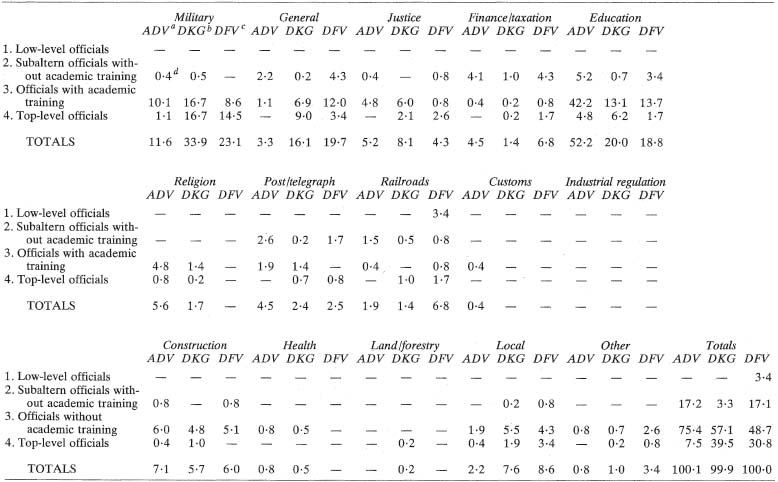

Table 5.3 Local Leaders of the Pan-German League in Public Administration

a Includes libraries, museums, and archives

b Includes harbors

c Includes mines and canals

Table 5.4 Years of Birth of National Leaders of the Pan-German League

| n | % | |

| Before 1840 | 13 | 18.6 |

| 1841–5 | 7 | 10.0 |

| 1846–50 | 7 | 10.0 |

| 1851–5 | 17 | 24.3 |

| 1856–60 | 9 | 12.9 |

| 1861–5 | 9 | 12.9 |

| 1866–70 | 7 | 10.0 |

| After 1870 | 1 | 1.4 |

| MV | 11 |

Table 5.5 Foreign Experience of National Leaders of the Pan-German League

| n | % | |

| Birth | 11 | 29.7 |

| Education | 4 | 10.8 |

| Residence | 7 | 18.9 |

| Extended travel | 11 | 29.7 |

| Marriage | 3 | 8.1 |

| Other | 1 | 2.7 |

| MV | 44 |

Comparing the local leadership in the Pan-German League with the rank and file of the same organization was difficult, for few membership lists survived. I found three-for Stuttgart in 1913,15 for the town of Königstein in Saxony in 1914,16 and for Hamburg in 1901.17 In addition, statistics that the League itself published in 1901 made possible a comparison at least by economic function between the cadres and the broader membership.18 I also compared these groups to all the men in the League whom I could identify as ‘long-term activists’. These were men whose activity I could trace for a period of at least five years. Details of all these comparisons are in Tables 5.9, 5.10, and 5.11.

I also compared patterns of public employment in the local leadership of several patriotic societies. As in the previous comparisons among patriotic societies, the figures in the Table 5.12 were drawn from the twenty-five select communities.

In a large number of cases I determined the specific offices held by leaders of the local chapters of the Pan-German League. The breakdown in Table 8.1 reveals that the higher offices usually were in the hands of men of higher status and that this pattern prevailed at the national level as well.

Determining patterns of cross-affiliation among different patriotic societies presented difficulties. Only in Hamburg did I find complete local membership lists for several of these organizations, but even these were not entirely comparable documents. I compared the membership list of the Hamburg chapter of the Pan-German League for 1901,19 the local School Association’s register for 1903,20 the Language Association’s membership list for 1912,21 the records for payment of dues in the Navy League for 1909–13,22 and the lists of local guests attending the annual convention of the Colonial Society, which met in Hamburg in 1912.23 One problem was that these lists did not cover a uniform period of time; another was the difficulty of identifying the same person on more than one list–a difficulty caused by similarities of name, job changes, retirements, sibling relationships, and misprints. I attempted to match first names and initials and occupations wherever these were listed, but I encountered many instances – of names like ‘F. Schmidt, Kaufmann’ or merely ‘Dr Müller’ – in which I was compelled in the last resort to guess. Subject to these caveats, the results of the survey of patriotic societies in Hamburg are in Table 9.1.

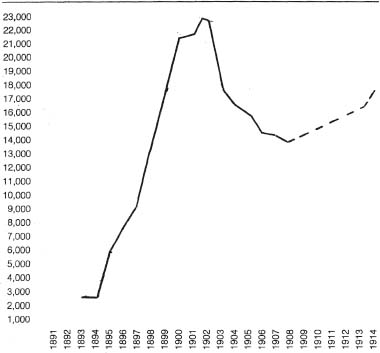

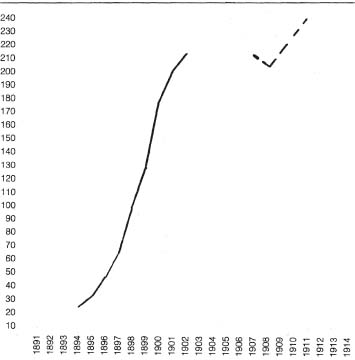

The membership figures and the number of local chapters, which I have plotted in Figures 10.1 and 10.2, came mainly from the Alldeutsche Blätter. For the years after 1903, when the published statistics began to misrepresent the situation, I calculated approximate figures on the basis of membership dues reported in annual budgets.

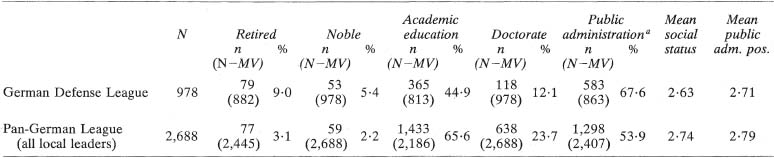

Finally, I drew the statistics on the German Defense League from reports of local chapters which appeared in this organization’s journal.24 For purposes of comparison, I ran the figures on the Defense League’s local leaders next to those of all the Pan-German League’s cadres in Tables 11.1, 11.2, and 11.3. I also compiled a more detailed analysis of the men in the Defense League with military occupations. This information appears in Table 11.4. Discrepancies between the figures in Table 11.4 and those in Tables 11.1, 11.2, and 11.3 were due to the fact that several of the officers in the Defense League held reserve commissions and listed both their rank in the reserves and their civilian occupation. In the first three tables I coded them by their civilian occupation; in Table 11.4 I used their military rank. In Table 11.5 I tabulated information about leaders of the Defense League in the public sector.

Table 5.6 Characteristics of Local Leaders of Patriotic Societies (and the German Peace Society)

a Includes parliamentarians and those whose occupations were ‘beamtenähnlich’.

b No chapters in Eisleben, Heppenheim, Moers.

c No chapters in Eisleben, Heppenheim, Minden, Moers.

d No chapters in Barmen, Darmstadt, Düsseldorf, Eisenach, Eisleben, Heppenheim, Minden, Moers, Pirna, Plauen.

e No chapter in Heppenheim.

Table 5.7 Economic Functions of Local Leaders of Patriotic Societies (and the German Peace Society)

Table 5.8 Social Status of Local Leaders of Patriotic Societies (and the German Peace Society)

Table 5.9 Characteristics of All Local Leaders and Long-Term Activists in the Pan-German League and of Members in Three Chapters

a Includes parliamentarians and those whose occupations were ‘beamtenähnlich’.

Table 5.10 Economic Functions of All Local Leaders and Long- Term Activists in the Pan-German League and of Members in Three Chapters

Table 5.11 Social Status of Local Leaders and Long-Term Activists in the Pan-German League and of Members in Three Chapters

Table 5.12 Local Leaders of Patriotic Societies in the Public Service

a ADV: Pan-German League. n = 268

b DKG: German Colonial Society. N = 420

c DFV: German Navy League. N = 117

d All figures are percentages of N.

Table 8.1 Hierarchy in the Local Chapters and National Offices of the Pan-German League

Includes deputy secretary or deputy treasurer.

The discrepancy between the sum of these two figures and the total number of local leaders is due to the fact that many local leaders were not listed by specific office or were listed simply as ‘members of the board of officers’ (Vorstandsmitglieder or Beisitzender). Includes parliamentarians and those whose positions were ‘beamtenähnlich’.

Table 9.1 Patterns of Cross-Affiliation among Patriotic Societies in Hamburg

a This figure is the percentage of the organization in the column (in this case the Colonial Society) made up of members of the organization in the row (in this case the Pan-German League).

b This figure indicates the proportion of the organization in the column that is made up of men with multiple memberships. It is not a straight percentage, owing to the fact that some men were members of more than two patriotic societies.

Figure 10.1 Membership in the Pan-German League, 1891–1914

Figure 10.2 Local chapters of the Pan-German League, 1891–1914

Table 11.1 Characteristics of Local Leaders of the German Defense League

a Includes parliamentarians and those whose positions were ‘beamtenähnlich’.

Table 11.2 Economic Functions of Local Leaders of the German Defense League

Table 11.3 Social Status of Local Leaders of the German Defense League

Table 11.4 Army Officers in the German Defense League

a Unless otherwise indicated, these figures are percentages of the total army officers (N = 129).

b These figures are percentages of the officers in each grade.

c The discrepancy between this figure and the sum of the first three columns is due to the fact that several of these officers were listed as both reserve and retired.

Table 11.5 Local Leaders of the German Defense League in Public Administration