Bad vibrations

Games

Music stirs, dramas shock, stories break the heart – only video games make us doubt our own humanity. Kyle Munkittrick

explores a discomfiting new art

The way we tell our stories has changed. From the oral tradition of Homer to the novel to radio, movies and television, we have found new ways to engage in the great conversation, and video games – interactive and social – are the future of storytelling.

Let’s start with the obvious: video games are art. Are they art the way a novel or a painting is art? No, of course not. Art has myriad manifestations and you have to approach each art on its own terms. I cannot criticise the cinematography of Melville any more than I can critique the character development of Kandinsky. Early video games were just that: games you played on a video screen. Like chess or backgammon, there may have been a veneer of story to give shape to the abstract pieces (white kingdom vs. black kingdom, spaceship vs. asteroids), but there was no real narrative.

Half a century has gone by since Pong

and Space Invaders

. In a world where games like Grim Fandango, Deus Ex, Half-Life, Portal, BioShock

and Mass Effect

not only exist, but are billion-dollar blockbusters experienced by millions of people worldwide, one thing is obvious: video games are no longer simply games. They a new artistic medium built around interactive narratives.

One of the key components of art is the exploration of emotion. Music, painting, drama, poetry and dance all attempt to stir, trigger, and otherwise excite and draw attention to our emotions. In that emotional exploration, what do video games do differently?

At each crux of a gaming narrative the player makes a choice. Daniel Erickson of BioWare

noticed that giving a player agency leant significant emotional weight to whatever action followed. The action didn’t have to be spectacular. The emotions assuredly were. While choice-based RPGs like Mass Effect

are obvious (and excellent) demonstrations of how choice impacts on narrative, two other recent games, BioShock

and Portal

, do something quite different and equally stirring by exposing and then removing player agency at critical junctures.

In BioShock

, as in most video games, you the player have an ally who provides suggestions, main objectives, and exposition throughout the game. As in most games, you simply trust this person from the outset and obey every command without question. This ally, you assume, surely has your best interests at heart. The penultimate climax of the game contains an astounding volte-face in which a simple phrase uttered by the ally – “Would you kindly…” – makes it impossible for the character you control to disobey his request. Suddenly, your controller sits limp in your hand as the character you have embodied and controlled for well over twenty hours of game play suddenly acts in direct opposition to your desires. Every choice you have made up to this point exposes your lack of moral reflection; you have, after all, failed to ask yourself, with any seriousness, who to trust, who to help, and who to kill.

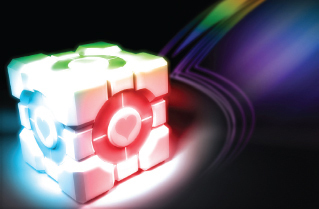

In Portal

a similar moment occurs on a level that requires you, the player, to carry around a steel box with hearts emblazoned on each side. The disembodied narrator, a crazed AI named GlaDOS, forces you to obey, under penalty of death. (You are under no illusion that your “ally” is trustworthy.) Throughout the level, the guiding voice of GlaDOS chides you for caring about the box, for thinking that it is talking to you, and for having given it a name. The character you play in Portal

is mute, meaning GlaDOS is mocking the thoughts in your head, not the character’s. At the end of the level, you are required to toss the steel box into an incinerator. Should you hesitate, GlaDOS further ribs you for your ludicrous attachment to an inanimate object. In that you have no other option should you wish to play other levels, eventually you will either incinerate the box or you will shut off the game. Upon disposing of the box, GlaDOS congratulates you on being the fastest of all experimental subjects in killing your friend, the steel box.

What is astounding in both scenarios is that the player’s emotions are triggered, not by their choices, but by how

those choices were made. These games demand that players reflect on their previous actions and cast those decisions in a new light. The issue is not that the choice was made, but that the player felt little remorse in making that choice; or, perhaps, despite remorse, did so anyway; or, worse yet, that despite total opposition to the process, the player complied anyway instead of terminating the game. I challenge Roger Ebert

to play either game in earnest and then tell me that the Companion Cube or “Would you kindly…” are not masterful commentaries on how illusory the moral context of our choices can be.

Games have exceptional narrative power: to continue playing, you must sometimes take actions you oppose. I, the reader, am not culpable for the destinies of Romeo and Juliet simply because I turn the page. Games demand that we choose to take the action that gives the story weight. In that moment of confrontation – of “This is unfair! The game only gives two options and I don’t want to take either!” – we realise that our only way out is either through the narrative, or via the power button.

By throwing these rules in our way – rules we know to be programmed and designed – video games call our attention to the constructed narratives in our everyday lives. When we are presented with two choices and neither is desirable, we see the rules of the system laid bare. Daily decision-making is theoretically unlimited, but our obligations and the narratives we have constructed for ourselves are often as unbreakable as the rule sets of a video game.

Incinerating a steel box is not a crime; but not feeling remorse about killing something about which one should ostensibly care is a moral failing. The shudder accompanying this reflection is something only a video game can create, because it sets up a struggle between the player’s self-image, guilt manufactured by a psychotic, manipulative guide, and the player’s real identification with what they may perceive as a gap in their own emotional bindings.

Soon, video games will achieve the same level of narrative sophistication through social means. I don’t mean social in a vapid, FarmVille

sense. I’m thinking rather of cutting-edge “social” games that leverage huge player bases to tell a story that no single person could experience alone. Consider the nigh-on-impossible Dark Souls

, which has, as its premise, the fact that you will die. A lot. Still, your countless deaths leave a trail of warning, and your residual spirit can leave notes of encouragement and indicators of danger for those who come after you and, when you are resurrected, for yourself. Perhaps too life-like for the comfort of many, Dark Souls

requires you learn from the miserable failure of others. And, like life, you simply cannot be the only person playing it.

Video games allow us to explore just how our decisions are impacted by how we feel; and then, when done well, they demand we re-examine those very same decisions from a new emotional perspective. Unlike a Sherlock Holmes reveal or a musical crescendo, there is no new information; just a new emotion recontextualising the original situation. Now magnify this experience to include millions of players whose decisions significantly and irrevocably impact each other’s gameplay experience. Perhaps it is in that social function that the most majestic video game narratives will emerge.

Ethical decisions are not calm calculations. They depend upon emotional, social and informational cues. As art is a mirror for life, games give us a mirror for how we decide to live, with one critical twist: they show us that the rules are constructed and contingent. Our decisions are often forced, not by natural law or the Fates, but by our incomplete perception of our world. Within the context of the social game, we may yet see how flexible our values really are.