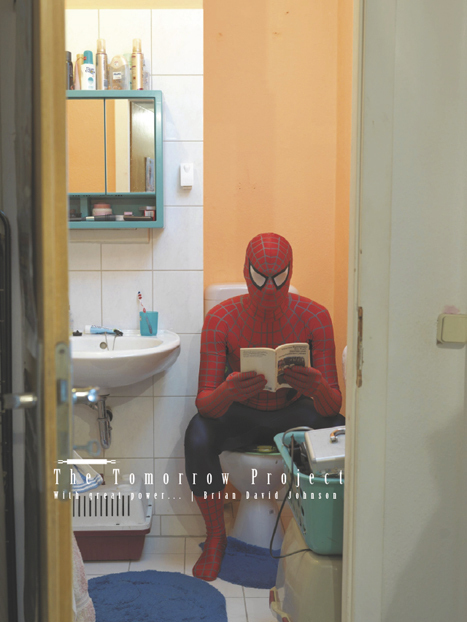

With great power…

Brian David Johnson

The Tomorrow Project

G

rowing up as a geek in the 1970s and 1980s, I was fascinated by comic books. It was a weird time. The shining Silver Age of the 1960s was over but writers like Alan Moore had yet to come along and teach us that comics and graphic novels could be serious fiction. So there I was, a little kid in rural America, waiting each month for my next issues to arrive. And those comic books taught me one very important lesson about life: being a superhero is complicated.

At that time the world of comics was split. You were a fan of either DC or Marvel. DC was known for a more science or gadget-based type of hero. Their bestseller was Batman, with his Batmobile and incredible utility belt. Marvel was known for its characters. Even though they might have superpowers and were out saving the world, Marvel’s characters still had the same day-to-day problems that we all face. I was a Marvel kid. To be specific, I was a Spider-Man kid.

First published in 1963, The Amazing Spider-Man

was something special. Lois Gresh and Robert Weinberg describe it in their 2002 book The Science of Superheroes

: “The first Spider-Man story was a radical departure for comic books. It may have been the first story in the genre that recognised that superheroes were people and as such didn’t always do the right thing. Or even the smart thing. That no matter how godlike their powers made them, their feet were firmly grounded in everyday life, and they had to deal with real-life situations.” Peter Parker, the geeky kid under the Spider-Man mask, was just like you or me. Physicist James Kakalios captures Spidey’s world perfectly in his 2006 book The Physics of Superheroes

: “Peter Parker would contend with seething high-school romances and jealousies, money problems, anxiety over his aged aunt’s health, allergy attacks and even a sprained arm (he spent issues 44 to 46 of The Amazing Spider-Man

with his arm in a sling), all the while trying to keep the Vulture, the Sandman, Doctor Octopus and the Green Goblin at bay.”

Average superpowers

I believe it is incredibly important that people become active participants in the future. We cannot just sit back and let the future happen to us. We need to have a vision for where we want to go and also an idea of the areas we want to avoid. Being a futurologist, it will come as no surprise that I am a geek. I love everything science and everything science fiction. Science-based, fact-based conversations about the future can help us build the future.

It was as I was reading the winning story of Arc

1.2’s competition – Nan Craig’s Scrapmetal

– that a couple of things occurred to me.

First, it was brought home to me that the collaboration between Arc

and The Tomorrow Project has produced an incredible competition. The quality of the writing, the diversity of the ideas and the depth of the conversations it has generated has been astounding. In keeping with the spirit of the project, I figured it was high time I put together a conversation about the winning story: you’ll find the full podcast of my conversation with writer Nan Craig and Victor Callaghan from Essex University in the UK and the Creative Science Foundation at uk.tomorrow-projects.com

. Do add your comments to the conversation. Tell us what you thought of the science and the fiction.

The second thought I had was this: that all the learned, scientific approaches we could take towards this piece – discussing its treatment of bioengineering, gene therapy and body augmentation and so on – while worthy, would entirely miss what for me was the story’s most important moment: the conversation Nia, the protagonist, has with a woman in her local employment centre.

Nia is looking for a job – any job – so that she can stay in her home town. She’s a perfectly designed killing machine used to “fighting alongside drones and crawlers, leading them, coordinating attacks”. But now she’s back, and the woman asks: “So, Miss Huws, what are your transferable skills?”

Well, there’s dismemberment, I said. How transferable is that? Can you find a job where I’d need to be able to kill fifteen people in fifteen seconds? Because I’m really good at that. Promise

.

I tried to look wide-eyed, innocent and keen. Instead I probably looked psychotic. I decide to throw in a bit more enthusiasm, so no one can say I didn’t try

.

Can I show you? I said, with as much adorable enthusiasm as I could haul up

.

In Scrapmetal

Nan gives us a world where we can all be superheroes. In fact, we all have to be superheroes just to keep up, and if we don’t develop some superpower, then we are going to be left behind. What happens, in this world, if you make the wrong decision about what superpower to develop? Or, worse, when your previous superpower – the one that made you invaluable on the battlefield – makes you useless, or worse, a liability, once you get back home? What happens when the world you were saving does not need you any more?

A life beyond limits

What superhero do we want to be? Do we want to be Spider-Man or do we want to be the Green Goblin? Created in 1964, the Green Goblin is Spider-Man’s nemesis. He is an inventor like Spidey, and his physical and mental abilities are enhanced, as Spidey’s are. The only real difference between to the two, aside from the costumes, is that Spider-Man has made the decision to use his powers for other people’s good while the Green Goblin looks out for himself.

Is the Green Goblin being so unreasonable?

The science behind Nan’s vision in Scrapmetal

will soon be realised. James Canton is a futurist and the CEO of the Institute for Global Futures

. In his 2006 book The Extreme Future

he explored the reality of the patches and enhancements Nan describes. “We have already started to adopt neuro-enhancements in the form of implants for neurological diseases,” he says. “Neuromedical devices will replace pharmacology with faster, safer, and more precise results. Human enhancement, the slow remaking of human beings into true cyborgs, will evolve as we move deeper into the new millennium.” Canton envisions a world where humanity focuses on longevity, extending the duration and quality of human life via biotech, stem cells, genomic drugs and even personalised DNA diets.

Be careful what you wish for:

Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow

(2004)

But as British science writer Brian Clegg points out in his 2008 book Upgrade Me

, our desire to alter and augment ourselves is not new. “This process of upgrading began in early humans through the natural pressure of survival rather than the result of any vision of building a superhuman future… they wanted to live longer, to become more attractive to the opposite sex, to be better able to defend themselves, to make the most of their brains and to repair their damaged bodies. Opposing these urges was the whole natural universe.”

We are technology. The powerful question Nan confronts us with is: What happens if we upgrade in the wrong way?

To explore this idea further I called Victor Callaghan. I’ve known Vic for years. He’s a professor at Essex University, where he’s worked on electrical engineering, robotics, artificial intelligence and intelligent environments. He’s used to exploring, among other things, programmed irrational behaviour in domestic robots. Vic is also the co-founder of the Creative Science Foundation

, which uses science fiction as a tool for the development of open-source AIs.

He told me: “In many ways, Nan’s vision is more disturbing than that of the singularity or making artificial robots that are smarter than humans. At least in my world, humans remain one natural, loving and wholesome entity. Our humanity is something we can cling to as the world descends into madness around us. But in Nan’s story, we are the technology and we are making changes to ourselves. I find that terrifying.”

Vic embraces the use of SF as a way to prototype different futures: “The story is reminiscent of people’s current use of cosmetics to enhance appearance to get jobs or their ideal partner. In this future we’ve moved on to augmenting human capabilities, and the consequences are much more serious. Nan’s story releases the competitive demons that our unaugmented selves are so good at bottling up. Having read Nan’s story,” Vic smiles, “I think I will stick to building wholly artificial machines! At least with them the lines are clearly drawn. In Nan’s story, the enemy is within each of us.”

Nan grew up in south Wales, and now lives in London. She studied politics at the University of Warwick and the London School of Economics, and was a student of the first Curtis Brown creative writing course. Scrapmetal

is her first published story, and she is working on her first novel, Déja

, about a woman whose memories predict the future. When she heard our dark interpretations of her story, she was both surprised and amused.

“It’s not a post-apocalyptic wilderness,” she counters. “It’s a world with grass and trees and love, as well as jobs – for some people. Like the real world, it’s brutal and nasty depending on your position in it. Like the real world, it’s a rather unforgiving place if you make a few wrong choices, or if you don’t have the financial means to do what you like.”

Nan goes on to explain: “When we are able to make changes to ourselves, some people are going to have the financial means to develop themselves in any ways they want, while others are going to be massively constrained, and their physical body is going to be shaped by the kind of job they might be able to get. Currently, the closest corollary in our world is education. If you train for the wrong thing, then it’s going to take time and money to retrain for a better career. Scrapmetal

is a more extreme version of that.”

The horrific, visceral reality of Scrapmetal

’s upgrades is that Nia can’t go back. She is alone, and desperate, and used. How do we help people who have been left behind? How do we make sure to train people properly for the future? In our relentless pursuit of efficiency and bettering ourselves can we – will we – make room for the ones that don’t fit?

Powers and burdens

At the end of the very first Spider-Man comic, Peter Parker has used his new-found superpowers to make some much-needed money as a professional wrestler. Peter is a little drunk on power. Throughout his whole life he’s been a scrawny kid and how he’s Spider-Man. As he leaves the wrestling match a crook bumps into him and Spider-Man just lets him run away. Peter is convinced that the crook isn’t his problem.

Cut to the end of the story: Peter learns that his surrogate father, uncle Ben, has been murdered by the same criminal that he let go free earlier – and the despondent Peter understands that his superpowers must be used for more than just his own interest.

In the last panel of the comic the legendary writer Stan Lee wrote “And a lean, silent figure slowly fades into the gathering darkness, aware at last that in this world, with great power there must also come great responsibility!”

We must always remember that we are human. Regardless of our superpowers, regardless of the powerful technologies we create, we must remember that these powers don’t make us less human. If anything, they make us more human, as we shoulder, with this new strength of ours, one novel and unexpected responsibility after another.

Comic books also taught me something else. The more human the superhero, the more powerful they are. Forgetting that makes for a really uninteresting comic – and a really dismal future.

Arc

has partnered with The Tomorrow Project, sponsored by Intel, to encourage readers to offer their visions of the future. This article was produced in association with The Tomorrow Project. Arc

retained full editorial control over its content. Brian David Johnson is Intel’s resident futurist and founder of The Tomorrow Project.