Chapter 14

MARMALADE ZEE’S HOUSE stood at the end of the long, tangled garden. Dog saw that it had once been beautiful: tall and elegant, with big windows and balconies, a steep, pointy roof and chimneys reaching proudly up into the sky, high above other, more ordinary, houses. But now it looked rather like its owner, crumpled and creased, as if it was just too much effort to stand up and keep all its floors and windows in straight lines. Many of the panes were broken, and one of the chimneys had fallen and made a big hole in the roof. Climbing plants had completely overgrown the doors and windows on the ground floor, so Marmalade led them, wheezing, along a sloping path that wound up to a terrace, level with the first floor. She pushed open a glass door with her stick and held aside a curtain to let them in: warm yellow light shone out into the blue-grey winter dusk, and Dog felt that, in spite of all its broken glass and crumbling walls, the house was still cheerful and ready to offer welcome.

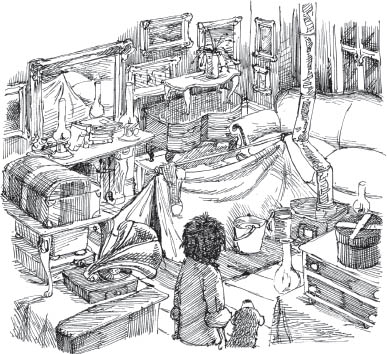

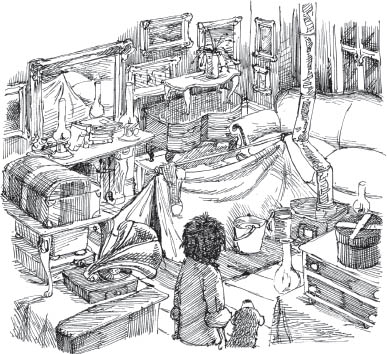

They stepped into a huge room lit by a number of hissing gas lanterns standing on the floor, and the last of the day’s light, gleaming faintly through huge windows that reached almost up to the high ceiling and down to the floor. The room was crowded with furniture, piled up in layers and towers and stacks, as if all the chairs and tables and beds and chests of drawers in the whole house had come into this one room for refuge. The only useable space was around a tent, pitched in the middle of the room. Beside the tent was a long sofa, and in front of it a fat-bellied stove whose wonky metal chimney disappeared through the ceiling between several enormous crystal chandeliers.

Marmalade waved a vague hand at the tent as she sank down onto the sofa. “Awful hole in the roof, but the tent keeps the water off!”

Dog didn’t need the explanation; she had never seen the inside of a normal house, and didn’t know that people don’t usually camp indoors.

She noticed that Marmalade had organized her room very cleverly, so that she could do most of what she needed to while sitting on the sofa: on one side of the stove, a bucket caught drips from a hole in the ceiling, and on the other, bits of broken furniture were piled in a large basket to fuel to fire. Marmalade had only to lean forward a little, as she was doing now, to put more wood on the fire (a fat section of table leg, carved in a spiral) and scoop water from the bucket into a kettle, which she plonked on the stove.

“There now,” she said brightly. “Tea in five minutes.”

Marmalade pulled a large biscuit tin out from behind the cushions. The smell of coconut macaroons drew Esme like a magnet. In a moment she had joined Marmalade and Carlos on the sofa and was munching happily. But Dog hung back, not sure how to fit in with another of Carlos’s old friends.

“Please,” Marmalade said to her, “come and sit with us. Any friend of Carlos is a friend of mine. Carlos and I have known each other for a very long time.”

“A very long time!” agreed Carlos.

Marmalade delved into the cushions behind her and pulled out a framed picture. “Look,” she said, holding the picture for Carlos to see. “Do you remember this?”

Carlos peered at it, first with one eye and then the other, flapped his wings and squawked, “Carlos!” he exclaimed. “Baby Carlos!”

Dog’s curiosity overcame her shyness. She climbed onto the sofa, accepted a biscuit and leaned in to look at the photograph that Marmalade held.

It was very sunny in the photograph, and very, very green, with lots of big plants and leaves all around the four people who stood looking out. Three of the people didn’t have many clothes on. They had thick fringes of dark hair and big smiles. One of them was a woman, one was a man and one was a child. The man held a pointed stick and wore some beads around his neck, and the woman had a pattern of red paint on her forehead.

Looking at these people made Dog’s heart race; she had never seen them before and yet something about them was familiar.

Between the man and the woman stood Marmalade, looking much less crumpled and creased, and with no orange gas bottle or tubes up her nose. Her red hair was long and shiny and caught up in a fat plait over one shoulder. She held her hands out like a cup, and in the cup was a parrot chick, with a big wobbly-looking head and a few tufts of feathers showing like dots of paint on its pink skin.

“It was taken a very long time ago,” Marmalade told Dog. “More than thirty years now. I was working in the Amazon, in South America, studying a tribe there, the Maohuri. Well, that’s what I said I was doing. Really I was a bit like you – running away!” Her laugh changed into a fit of wheezing and it was a few moments before she could speak again.

“I lived in a great forest by a river, with this family,” Marmalade continued, pointing a knobbly finger at the three people in the picture. “That’s Dawa and her daughter, Mankamo, and that’s Gikita – he was a fine hunter. And this,” she said, tapping the parrot chick, “is Carlos. Gikita climbed a tree to take him from a nest and gave him to me.”

Dog looked in awe at Carlos: he really was very, very old indeed!

“I didn’t want to take a parrot from its wild home,” Marmalade went on, “but the Maohuri kept lots of different animals – birds, coatis – and it would have been rude to refuse Gikita’s gift. Anyway, we were friends from the start!”

Carlos squawked again and flapped in agreement.

“We lived like parrots and coatis, all together under the trees.”

Marmalade’s face shone with this memory. Dog’s face was shining too. She didn’t know what tribes were, or Theamazun, or Sufmerika, but now she knew what Carlos meant when he said “home”. It was the place where he was hatched, a real place where parrots and coatis and people all lived together, free and happy. Dog’s heart did somersaults.

Marmalade took some more gasping breaths, and managed to say, “I would be living there still, but I got sick and I had to come back here. I never saw Dawa or Mankamo or Gikita again.”

“Carlos!” Carlos said, and Marmalade smiled.

“Yes, yes, I had you, Carlos – for a while at least!”

Carlos fluffed out his feathers and pulled his head into his neck.

“Yes, you remember, don’t you?” said Marmalade. “Flying off out of that window? I was so worried.”

“Came back!” Carlos rasped sulkily.

“Yes, you did after three years!” Marmalade waggled her finger at him and he caught it playfully in his beak. She laughed. “You old rogue!” she said.

The kettle on the stove began to whistle. Marmalade pulled a teapot, cups and more biscuits from under the sofa and behind cushions.

When the tea was made, Dog sipped, and dunked chocolate fingers, with all she had heard whirling around her head. She looked at Carlos in wonder. He really was ancient. But parrots lived a long time, so he wouldn’t die soon.

“I’m very glad to see you, old friend,” Marmalade was telling Carlos, “but I have the feeling you are not here to stay, are you?” She raised an enquiring eyebrow at Carlos.

“Home,” he said. “Home!”

“Yes.” Marmalade nodded. “I guessed that’s what you’d want. And you’ll take your friends of course. I haven’t seen a coati or a child like this since I left the Amazon.”

Carlos climbed onto her shoulder and looked carefully into her face. “Marmalade come too?” he said.

Marmalade’s eyes glittered with tears. “I’m too sick, Carlos. But I’m happy that you are going back at last.”

For a moment they sat in silence while Marmalade took several long breaths. Then she got to her feet.

“We must be practical,” she said. “You can’t go in an ordinary way. You will have to stow away on a boat. Luckily, just the right one is in port right now. Come and see.”

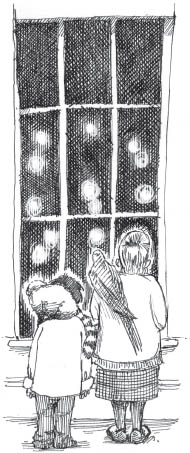

Marmalade pushed her gas bottle across to one of the tall windows, and Dog and Esme followed sleepily. It had grown dark outside. Dog looked out in wonder at the jumble of streetlights in the blackness.

Although Dog never knew it, the city where she had lived almost all her life was a great port, with huge cargo ships from all over the world coming and going to and from the docks. From Marmalade’s windows they could see the ships lined up ready for their cargos; the cranes; and dockworkers running about like ants under the floodlights; the dark sea and sky beyond. Dog didn’t really understand what they were looking at.

But Carlos did.

Marmalade looked through binoculars and pointed out the smallest ship moored at the dock, still huge but not the monster size of the others. “That’s the one,” she said. “The Marilyn. She crosses the Atlantic, then trades along the stretch of coast where your home-river has its mouth.”

“Marilyn,” said Carlos thoughtfully. “Marilyn.”

“She’s loading now,” Marmalade told him, “so she’ll sail tonight.”

Smoke puffed from the Marilyn’s chimney and her horn blew low and deep, signalling her readiness to depart.

“No time for goodbyes now, Carlos,” wheezed Marmalade. “You must hurry!”