Chapter 25

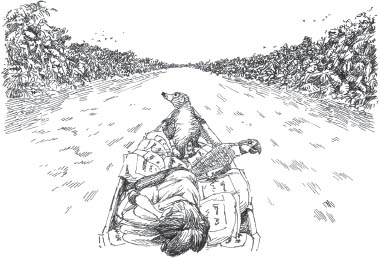

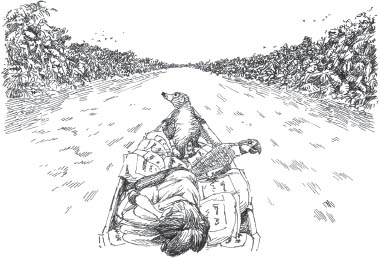

THEY CRUISED STEADILY up the middle of the mouse-brown river. The man, whose name was Hoehe, sat at the back, lazily holding the tiller and smoking little cigarettes. Dog and her friends sat in the prow, jammed in front of two sacks of rice and a huge tin of marmalade. The sky was a hazy blue and the air streamed over them, cool and heavy.

Once or twice a day Hoehe stopped at villages, dropped off supplies, and collected passengers or small cargo and replenished their water supplies to carry to the next stop. People were interested in the child and her two companions. They gave them food, admired the bird and petted the coati but mostly left them to themselves, up there at the front of the boat.

At night Hoehe moored the boat at little jetties or small beaches. He caught fish and cooked it over a fire, but never offered to share it. Esme found her own food, scrabbling in the muddy banks as if she’d been doing it all her life. Carlos cracked Brazil nuts lying in the bottom of the boat. Dog mostly went hungry.

At first the banks on either side were so far away that they were just distant walls of bright green. Occasionally flocks of white birds erupted from sand banks, or the movement of some animal flickered between the bank and the water, too far away to see properly. But as the days went on, the river narrowed and the banks got closer. Now Dog could see huge trees, with dark dipping branches tangled in leaves and climbers. Flashes of brightly coloured wings showed in the treetops. Once they passed a muddy bank where huge caimans were sunning themselves. Uncle had once bought a tank of baby ones for the pet shop. Dog had loved them, but had almost lost a finger or two giving them their dinner! She could understand why they had been so hungry if this was how much growing they had to do!

Esme, usually so ready for a snooze at any hour, hardly slept at all during the journey. She stood on the very prow of the bow, with her ears pricked and her nose pointing forward like a quivering compass needle. Dog could see she was soaking up every smell and sound and sight.

Carlos was excited too. He flapped his wings and even took off at times, circling the boat as if he wanted it to go faster. He seemed unable to be still for a moment. He said very little apart from mimicking Hoehe’s terrible singing or the puttering of the outboard. But at night he kept Dog company. He perched next to where she slept on the sacks of rice, so close she could hear him breathing and smell his warm, dry feathers.

Dog could see a change coming over her friends. Esme’s tail seemed stripier, despite the missing fur; Carlos’s feathers more like sky and sunshine than ever before. The life of the river and the forest was beginning to flow through them. Dog felt it too. She was filled with a kind of fizzing sensation, a mixture of comfort and excitement. She felt as if all her insides had been arranged into new patterns and then lit up, like Asky’s shiny sky-man, Orion.

Some nights Hoehe didn’t sleep, so they kept on going all through the warm darkness. Dog slept in fits and starts, waking to stars dancing on the water, Esme reaching her nose into the breeze or Carlos spreading his wings to the moonlight.

Dog didn’t count all the nights and days, but at last, one evening, when the sun dipped behind the trees, Hoehe steered his baraca up to a little jetty, where a cluster of grassy huts gathered on the river bank. Hoehe tied the boat up and pointed to a worn notice on a pole:

ZEE FOUNDATION MAOHURI RESERVE, it announced. ADMISSION STRICTLY BY PERMIT ONLY.

“I can’t go any further,” he said. “You’re a Maohuri, aren’t you, so you can get out here.”

Dog smiled and nodded, but of course she couldn’t read the notice. She understood, though, that this was the end of their journey.

Stiffly she unfolded herself and, with Carlos on her shoulder and Esme at her feet, got ready to climb out of the boat. She stared about, feeling that this was the strangest, and also the most familiar place she had been. The forest pressed in all around them, dense and huge and green, as if the trees had just stepped back a little so the huts could stand. The air was soft and moist, full of scents and the sounds of insects, frogs, birds.

But Hoehe didn’t let the little waif stare about her in that dazed way for long. He wanted his payment. It was obvious now that the child had no money and he was looking forward to the fat price that a talking macaw would make back in town.

“Where’s my money?” he said in Spanish.

Dog smiled and nodded, but Hoehe wasn’t smiling any more. He was tired now, and cross. He decided could probably sell the scrappy old coati too – and the girl, if it came to it.

“Where’s my money?” He stepped up to Dog and stood over her, looking much bigger and less wiry than he had seemed before. Suddenly Hoehe’s intentions were very clear. Dog knew all the signs – she’d learned them from Uncle. She felt small and sick. She hung her head and trembled. Esme climbed into her arms, chittering in fear, and hid her face in her tail.

Carlos stood on Dog’s shoulder and flapped his wings. “No money,” he said in Hoehe’s voice. “No money.”

Hoehe’s face froze. “OK,” he said, “then I take my payment.” He snatched up a big black box from the bottom of the boat in one hand, and Dog’s wrist in the other. “Give me the bird or I will kill your coati and slice out your heart and feed it to the piranhas. I’ve had plenty of birds and children in this box. You won’t be the first or the last!”

Dog didn’t understand the words, but she could see their meaning very clearly. Hoehe held the black box open. Inside were feathers of all colours – blue and gold like Carlos’s own, scarlet, green, even deep violet. There were signs of humans too – tiny hand prints and the marks of scraping nails.

There would be no escape for any of them, even for clever Carlos, from that box.

Dog was very, very afraid, but she had not come so far for a box like Uncle’s to swallow her or her friends at last. With all her strength she kicked the black, black box, and it spun from Hoehe’s hand, over the side, and sank. At the same moment Esme reached out from behind her tail to sink her teeth into the hand that held Dog’s wrist. Hoehe yelped in pain and let go. Dog shoved Carlos off her shoulder so that he could fly, leaped onto the jetty with Esme and ran.

Hoehe had been sure his bullying would work on this little scrap of a girl. So it took him a moment to recover from the surprise of her sheer cheek; then he was after her, blood dripping from his hand as he gathered speed. His strong boatman’s legs worked like pistons, and his moustache set in a determined line. If he couldn’t catch the bird, he was sure he could catch the girl.

Dog ran up the jetty and straight into the middle of the village, between the little huts made of wooden poles and grass. Something about the place made her feel instantly safer, more certain that she could escape.

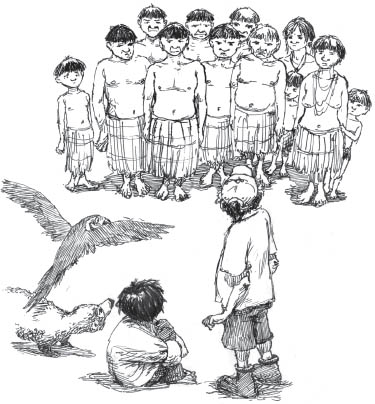

People like those in Marmalade’s photo stood in doorways or lazed in hammocks, and they all turned to watch the little girl run by with her coati at her ankles. Not such a strange sight, but the gold and blue macaw screeching just above her head was a bit unusual.

On she ran, with Esme panting beside her and Carlos circling above, but Hoehe had longer legs. Just where the village turned again to jungle, he caught her. He clamped one hand in her hair and dragged her back towards the river.

Carlos yelled and dived-bombed him. Esme snarled and slashed at his legs with her claws and teeth.

Now Hoehe was really angry. He shook the brat, wanting to pull out her hair by its miserable Maohuri roots. He kicked and waved his free arm to try and ward off the bird, but Carlos was devilishly clever at avoiding his blows.

The villagers rushed towards the commotion, their curiosity aroused. Hoehe found his way back to the river blocked, as every family had come out to see what was going on.

“So,” said Moipa, the village head man, in Spanish, “what’s all the fuss?”

“Step aside, Indian scum,” said Hoehe (who was sure that he was descended from the Spanish conquistadors).

The villagers had never much cared for Hoehe – he always overcharged them for goods transported up the river – so his lack of manners drew even more attention. They closed in around him a little more: they didn’t like the way he was holding onto the child, who looked just like one of their own, or the way he had hit out at her animals.

“I think you should let this child go,” said Moipa.

“Child? She’s a thief. She tricked me. I brought her upriver because she said she’d pay me with that bird.” Hoehe pointed to Carlos, still trying to dive-bomb him.

Moipa turned to Dog. “Is this true?”

But Dog didn’t answer.

“It’s no good asking her,” Hoehe grumbled. “She’s a mute!”

“But you said she told you she would give you the bird,” said Moipa.

“Yes,” added his wife, Akawo. “How did she do that if she’s a mute?”

Hoehe opened and closed his mouth like a landed piranha. He let go of Dog’s hair, and she dropped to the floor beside Esme. Carlos swooped down onto her shoulder, and Esme sat at her feet.

“Give me the bird,” said Carlos, in Hoehe’s voice, “or I will kill your coati and slice out your heart and feed it to the piranhas. I’ve had plenty of birds and children in this box.”

Horrified gasps and murmurs spread throughout the crowd – which was now almost everyone in the village.

“I see,” said Moipa. “I think you’d better go, and never come back.”

“Yes!” added the villagers. “Go!”

“You don’t have a permit to be here anyway!” added Akawo.

Hoehe shook his fist and crossed himself, then he turned and fled. Esme chased him, snarling, her bandaged tail up, all the way back to the river.