Documents and Imagery

Archaeology abounds not only in artifacts from the past but in modes of documenting and studying them. In this chapter, we look at the way visuality works in archaeology, from the graphics, maps, and photographs themselves to the roles they play. Along the way, we question the stress placed in much discussion of visual media on their mimetic and representational qualities—that is, their fidelity to what they are taken to represent and their degree of correspondence to what is represented.

Looking at what might be called the political economy of visual media—the work they do in archaeology through networks of production, circulation, transaction, and articulation—also leads us to identify some of the implications of emergent digital media, not for more spectacular summations of data about the past, but as open forums for the co-production of pasts that matter now and for community building in the future.

A basic premise of all archaeology is that archaeologists need to record and publish what they find. Through excavation, through the displacement of artifacts into collections, acts of conservation, or even in the course of surveying a site, as archaeologists, we simultaneously affect and change that which holds our interest. In this, there is often a rather peculiar trade-off: in working with things, in laboring toward their display, we participate in their destruction.

In the archaeological relationship between the things of the past and present that lies behind this idea of the “unrepeatable experiment” is a distinctive experience of immediacy—a notion of “discovering” the past in its material remains. This is the time of connection or engagement, the relationship of material duration and present engagement. Two terms that describe this temporality are “actuality” (Benjamin 1996b, 473–76), the juxtaposition of two presents, that of the past “as it was” back then, and that of the present, as we turn with interest to the past, and the kairos, or time of connection, between past and present (and that key opportune moment when the past appears to us).

Visual media are indispensable in the process of documentation, that is, the practice of transforming the things of the past into manageable, malleable forms. From reconnaissance surveys to excavation of features to laboratory analyses and interpretation of glyphs, the work archaeologists perform could not be accomplished without proxies of our vision of the past. This holds all the way from research methodology and project planning to information design and presentation of results. Understanding the past, making archaeological knowledge, is primarily about the process of making and using media.

Archaeology is about working on what’s left of what was; archaeologists do not simply discover the past. The things we deem to be of the past are often on the move (see also chapter 6). Taking it up, sorting, classifying, counting, drawing, and measuring so that we can discern relationships, patterns, quantities, and changes are what archaeologists spend much of their time doing. This is an especially important part of designing quantitative information (Tufte 1997, 2001). But it is no less an integral part of engaging with the past through more affective means; the theme of the ruined past in the present, for example, has consistently proved to be a prominent component of landscape imagery in the West since the seventeenth century (Andrews 1999; Makarius 2004).

The archaeological process can be described as one that moves through a continuity of material worlds that run from ruins and remains to two-dimensional “proxies,” those “stand-ins” for the material world that comprise the world of our media. It is more about crafting what remains of the past into “deliverables” (Shanks and McGuire 1996), into texts, graphs, maps, drawings, or photographs: this is the work of visual media in archaeology. Yes, there is, of course, the crafting of artifacts, material remains, and project archives, but much effort is required to produce the outcomes, those two-dimensional deliverables. It ought to be recognized as a highly skilled process akin to (reverse) engineering. Yet archaeologists tend to truncate this long sequence of workings on the past, these “serial orders of representations” that get us from the henge monument, the wall line, the abandonment level, or the storage pithos to the monograph, article, report, and web site (Lynch and Woolgar 1990, 5). Archaeologists mainly focus on the final products, particularly those that summarize and argue for a particular point of view or interpretation. We elide numerous transformative steps linking different media and their referents (Witmore 2004b). We “black box” the archaeological process as if there were only “inputs” and “outputs,” with little inspection of the messy middle (Latour 1999, 304). Excavators, whether skilled or unskilled laborers, technicians, consultants, curators, and the many other specialists involved in archaeological engineering never act alone, however—archaeology’s productive forces involve the actions of a complex host of characters. A political economy of media would recover the work done by our mundane plans, maps, photographs, narratives, and archives.

This elision is, of course, most often a practical necessity. Research cannot return every time to raw data sets, to first principles, to the minutiae of every project archive. We do have to rely on media that gather, articulate, and simplify the inexhaustible richness encountered in dispersed sites, collections, and archives. Our point is that unpacking the work puts stress upon the process of archaeological research, upon principles of traceability, upon this in-between, rather than the exclusivity of the ends, those ideas of verisimilitude or “seeing the past as it was.”

Archaeological work is connected to an ethical imperative to record authentically, with fidelity. Because archaeologists transform what remains of the past through their collective work, displacing and irrevocably transforming cuts, deposits, and features, they most often give epistemological primacy to the material remains: a drawing or photograph is considered secondary or a means to the actual things of the past, even though we could not construct knowledge of the past without such media. This makes visual media supplemental in a Derridean sense (Derrida 1976). The archaeological image is akin to a prosthesis—an artificial substitution to replace a loss or absence. The past cannot be known without media, and archaeology works in this charged middle ground—a fundamental point that lies behind our elucidation of the political economy of archaeological media.

The epistemological deferment to the “original” past accompanies a strong commitment in archaeology to a particular kind of representational accuracy, one that is technologically enabled and based upon a correspondence theory of truth. The translation of experience of archaeological remains, with all their complex qualities, into media frequently relies upon technologies (from geophysics to photography), instruments (from ground-penetrating radar to theodolites), and upon reproducible protocols and standardized procedures (from cartography and architectural surveys to cataloguing and finds drawing) that are taken to guarantee accuracy. There is often an early and thus enthusiastic adoption of media technologies in archaeology, whether it was the printed illustrated book, or systematic cartography, photography, and other forms of remote sensing, or more recently, architectural and virtual reality (VR) software. Consider again the work of Charles Thomas Newton with photography at Halicarnassus, for example (see chapter 3). Media artifacts produced with the aid of technology are most often evaluated in archaeology according to their degree of correspondence with what they represent, their mimetic qualities. These qualities are amplified in those cases where the human hand was removed from such processes. Consider Stuart Piggott’s summary of the impact of photographic processes in the context of draftsmanship and illustration:

From the beginning of printing all illustration (save in the exceptional circumstances where the original draftsman also made his engraving) interposed two interpreters between reality and the reader—the primary artist, and the craftsman who cut a block of soft wood across the grain, or engraved the end-grain of a hard one, or engraved, etched, mezzotinted, aquatinted or lithographed on metal or stone. With the introduction of the photographic processes, especially those of black-and-white line blocks, the original drawing could be transmitted in facsimile, or at most reduced in size, without passing through another person’s mind. (Piggott 1965, 172)

We shall take a contemporary theme in archaeological visualization in order to examine the features of this commitment to “making increasingly accurate copies of what they depict” (Harman 2009a: 79). Since the 1980s, archaeologists have enthusiastically adopted software that enables 3D modeling and rendering. Coming out of professional architectural and engineering practice (computer-aided design) and the media industry (computer-generated imagery), increasingly affordable systems allow the creation of photorealistic simulations of ancient buildings and landscapes on the basis of archaeologically generated data. And not just on a computer screen; wearable media devices offer the possibility of more immersive simulations: Pompeii regenerated on a visor display, in the ruins themselves (see Raskin 2002; Siewiorek, Smailagic, and Starner 2008; Witmore 2004a, 2009). Accuracy can certainly and appropriately be correlated with the faithful witness of the photograph, because it effectively captures the style of things as they are seen. If the past is decaying and perpetually perishing, the attraction of an arrested or copied past to gaze upon is evident, even, as with photos of loved ones, comforting.

Virtual Reality experiences, typical of gaming and entertainment software, are making their way rapidly into archaeology and cognate fields (Forte and Sillotti 1997; Frischer and Dakouri-Hild 2008). In the last quarter of 2008, for example, Google offered 3D modeling of ancient Rome, superimposed upon their topographic and satellite imagery in Google Earth and based upon archaeological research and data processed at the University of Virginia. Visit Rome on your computer and you can fly through the ancient city of 320 C.E. Such visualizations complement CAD (Computer-Aided Design) simulations. Second Life, an online world, has grown rapidly since its launch in 2003 to become one of the Internet’s most discussed manifestations of VR. It has several archaeological and “recreational” sites of antiquity. To explore the issues of VR in archaeology, in 2006 the Metamedia Lab at the Stanford Archaeology Center, in affiliation with Stanford Humanities Lab, undertook an experiment in constructing an archival facility in Second Life.

Life Squared, built on an island in the online world Second Life, is an archaeology of an artwork made by Lynn Hershman Leeson and Eleanor Coppola in 1972. In the Dante Hotel in San Francisco, Hershman Leeson created an installation of artifacts, traces, and remnants, posing questions of who had been there and what had happened. In 2005, Stanford University Special Collections acquired the artist’s archive, which included what was left of the installation—texts, photos, artifacts. As part of the Presence Project (Gianacchi, Kaye, and Shanks 2012), an international interdisciplinary collaboration researching the archaeology of presence, the Daniel Langlois Foundation funded the reconstruction of the 1972 art installation at the Dante Hotel in 2006 in Second Life (fig. 5.1). This “animated archive” has since appeared at the Montreal Museum of Fine Art and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (Frieling 2008).

Life Squared thus addressed questions of how to treat archaeological or archival sources as the basis for the reconstruction, replication, or simulation of an “original” experience and event: questions of how we might revisit the “presence” of an experience or event, in a “kairotic” connection, as previously defined. A context is the future of the art museum in the absence of a self-contained artwork (facing the question of how to curate “an experience”). Conspicuously, Life Squared is an experiment about modeling and simulation—core epistemological practices in archaeology.

FIGURE 5.1. Screen shot from Lynn Hershman Leeson’s installation at the Dante Hotel, San Francisco.

An obvious option was to simulate the hotel of 1972 photorealistically so that avatars might rewalk the corridors as if they were there back then. Most of the VR experiences in Second Life aspire to photorealism. But we chose another option. In order to remain faithful to the fragmented remains, and in order to open up the 2006 experience to new associations (the actuality of the past), we traced out the surviving floor plan of the building and located the archived images and documents of the 1972 installation in a skeletal wire frame, reconstructed only to the extent attested by the sources. The fidelity to the original hotel of 1972 is highly selective; the hotel of 2006 in Second Life does not look anything like the original, yet it is empirically sound and contains nothing that cannot be verified. The result is something of a dissonance with the sunny photographs we have of the San Francisco street of 1972. Instead, it shares the ghostly light of Second Life of 2006 filtering through the digital ruins of a building hardly attested to now in any record or archive.

With respect to visualization, rather than a stand-for, substitute, or replica of the original, we chose to treat the “virtuality” of this online world as an opportunity for reiterative engagement, for people to come to a fresh participatory experience (Frieling 2008), connecting then and now. The intention was to open up the past to new interests and involvement, with avatars in Second Life revisiting and reworking the past on the basis of the surviving traces. A broader argument concerns the transitive character of information. Life Squared is based upon the premise that the information rooted in singular archives needs to be worked upon if it is to survive. Left in museum boxes in storage depots, sources will gather dust, molder, and decay. Information requires circulation, engagement, and articulation with the questions and interests of a researcher. “Inform” is a verb, not a substantive. Life Squared was explicitly treated as an experiment in “animating the archive.”

Like an archaeological excavation, Second Life is a performance space indebted to visual media. We treated the space not as a representational medium, an animated 3D image, but as a prosthesis, as defined above, a cognitive instrument for probing this particular connection with the past. This shifts attention from visuality per se, the experience of forms and textures and the quality of the photorealism (aspiring to the response that “it surely did look like that”), to the specifics of how the traces of the past connect with the present, the avatar visiting the “hotel” of 2006 in a particular encounter located in the expectations and experiences of that avatar and his or her owner. This is to treat such a 3D world as a mediating space, and the construction of an archive as a co-productive project involving curator, the artifacts, and the visitors or users.

Another context for this project is the genre of theatre/archaeology, defined by Pearson and Shanks (2001) as the rearticulation of fragments of the past as real-time place-event, and sharing an interest in memory practices as part of a distinctive trend in contemporary fine and performing arts (Enwezor 2008; Giannacchi, Kaye, and Shanks 2012; Kaye 2000). This type of theater/archaeology is exemplified by Tri Bywyd (Three Lives), an ambitious assemblage of three portfolios of evidence put on by the performance company Brith Gof in the archaeological remains of a farmstead deep in a Welsh forest in 1995. Mediated by five performers, three architectures, an amplified sound track, various props, including flares, buckets of milk, a bible, a revolver, and a dead sheep, the three portfolios envision the “Welsh Fasting Girl” Sarah Jacob’s death in 1869; an anonymous Welsh farmer’s suicide in 1965; and the murder of Lynette White in Cardiff in 1988 (Kaye 2000, 125–38).

The explicit purpose of the work was to visualize and make manifest the subtleties of these archaeological/forensic narratives, but not to simulate or represent, or indeed to explain. The work’s aesthetic, in common with much contemporary art, was not at all mimetic. “Three Rooms” (Shanks 2004) was another experiment in the documentary articulation of three forensic portfolios that eschewed any mimetic visuality, plot or character, but hinged on performance and the burden of work carried by memories and traces, albeit set in the long tension between urban and rural experience.

We needn’t look only to the contemporary visual and performing arts for a critique of photorealistic mimesis. The impact of Foucauldian notions of discourse and the growth of the interdisciplinary field of media studies has resulted in a substantial body of critical reflection upon representations in archaeology (Clack and Brittain 2007; Joyce 2002; Molyneaux 1997; Smiles and Moser 2005). For instance, Stephanie Moser (2001) has brought discourse analysis to the visual conventions or visual language of archaeology. Timothy Clack and Marcus Brittain (2007) have taken a cultural studies approach, highlighting the manner in which popular appropriations of archaeological information have a “dumbing down” effect on representations. (On the other hand, they equally emphasize that archaeological representations must be communicable to an increasingly interested public). This critical examination of archaeological representation is important. Indeed, a self-critical orientation steers us away from historical and cultural biases—such as the portrayal of Pleistocene “man the hunter” or other conceptions based upon patriarchal, sexist values (Gero and Root 1990).

Such appraisals generally end by distinguishing between “popular” and “pedagogical” representations, on the one hand, and “inter-and intra-specialist” representations, on the other (Clack and Brittain 2007, 31). This seems to imply that representations geared toward popular communication inevitably stray from certainty, while others stick closer to the data. Of course, it depends on the image or graphic, but is there a datum that can be taken as the origin of a representation? Perhaps it is simpler to ask more broadly: just what are we representing with our visual media in archaeology?

Certainty and assurance also motivate archaeology’s desire for photorealism. The belief in representing the things of the past, or, indeed, the past as it was, with fidelity, is coupled with the need to discriminate between different renderings. Expressions of archaeological epistemology have variously revolved around the notion of epistemic fit to the material past (Wylie 2002). In a concern to achieve more accurate or nuanced representations of ruins, vestiges, and artifacts, archaeology has moved in a historical trajectory in the development of its theory and methodology along with other natural and social sciences. Driven by ocular analogies, the pursuit of the “mirror of nature” (Rorty 1979) has involved the sciences in perennial questions of “representation and reality” (Putnam 1988). Philosophers of science have characterized such inquiry as the summum bonum of modernist epistemology. The reasoning and motivation is not misplaced: such a principle of representation as copy grants evaluative capacity to knowledge claims. Better representations are judged to match, hook onto, mirror, or correspond to an external reality. Therefore, better representations may be evaluated by peers as superior according to how they fit with the material world and the memories it holds of the past.

Such a conception of knowledge is very difficult to get to work. More specifically, knowledge claims do work; they just don’t work by demonstrating any epistemologically privileged relationship with an external and removed reality. We sidestep the problem by refusing the radical distinction between the past and our claims to know it. This is not to question the reality of the past by asserting that we construct it. It is simply to question a modernist epistemological tradition that presumes an ontological rift between people and things, between internal minds and external reality, between the past and the present, between what we do (as archaeologists) and how we represent this practice. And if we sidestep such a deeply rooted epistemology, we avoid a theory of truth that rests on the correspondence of words with the world and bolsters a faith in representational proxies that “stand for” things.

In this shift away from questions of epistemology, the answer to the question of whether there is a datum, an origin to archaeological “media-work,” is clear. The idea of a “record” waiting to be passively recovered and represented is too simple. It begs the “Pompeii Premise,” an assumption that there is an inert, static “past” to be represented, free from the kinetics of ever-present distortion (Binford 1981; Schiffer 1976). Thoughtful archaeologists have been long aware that the “archaeological record” is something created through the work of making media. Transforming the dynamic and materially complex ruins in the landscape into media artifacts releases something of them into circulation as “immutable mobiles” that may be taken back to our laboratories, offices, and archives (Latour 1986; see also Lucas 2001a; Witmore 2006). These immutable mobiles are not copies, means to ends, or intermediaries. Rather, they are translations, the means and the ends, and full-blown mediators (see Latour 1987, 2005).

Several discussions regarding the complexity of archaeological science are relevant here: Michael Shanks and Christopher Tilley (1987) introduced the notion of archaeology’s “fourfold hermeneutic” to capture something of these transformations; Lewis Binford (1977, 1989) and Michael Schiffer (1988) debated the character of the “middle-range theory” required to articulate past sociocultural processes from remains that had been subject to the transformation of natural and social origin; Linda Patrik (1985) and John Barrett (1988) contested even the reality of an “archaeological record” (now see Lucas 2012). The ethics of heritage interests and their impact upon what is left of the past are in the forefront of concern in archaeology’s professional sector today. Visual media and representations occur throughout this manifold of operations performed upon what remains of the past.

Asking whether there is something that we are ultimately representing in our archaeological work, questioning the nature and origin of the archaeological record and determining our epistemic relationship to it, certainly provokes us. The particularity of archaeological work centers upon the “kairotic” temporality we have outlined, upon the relationship of artifacts and sites to social, cultural, and historical change, and upon the processes of decay and entropy that remains of the past undergo.

This transformative power of visual media is amplified through digitization. And the extraordinary power of digital media is perhaps encapsulated in geographical information systems (GIS) and VR software, which offer the potential of connecting data to spatial coordinates, fleshing out site and landscape, and rendering simulated pasts in photographic detail, all on the scale of world building—as complete a model of the past as possible; a “digital heritage” (Webmoor 2008). We might become enthralled with the “cool factor” and get caught up in a technological optimism aiming at such simulation and accept mimetic correspondence as achievable, at least in some circumstances (Solli 2008). But the epistemological conundrums remain, and we suggest that it is better to think of archaeological work in a different way, not as mimesis, modeling, simulating, or representing, but as a fundamental transformation or translation, work done in the spaces between old things and the stories they hold in the present—mediation.

Support for this view of representation in archaeology comes from a range of work in science studies and cognitive science. Early modern experimental science was wrapped up in “natural magic.” Prescientific instruments were frequently popular parlor tricks. Magic lanterns, the camera obscura, and Robert Boyle’s vacuum pump were employed for entertainment and edification.1 Nevertheless, such popular technologies came to be valued for their capacity to augment the human senses and inscribe what they registered at the boundaries of human perception. Early demonstrations to gatherings of peers were intended to show the matters of fact under consideration through viewing and witnessing the instruments themselves. These ocular demonstrations relied upon common and shared experience for the settling of disputes concerning hypothesized entities and natural philosophy.

As considerations of nature became more abstract, delving into matters of cause and effect, instruments increasingly had to produce visual outputs. By the end of the eighteenth century, demonstrations gave way to recording instruments that mechanically translated relationships into visual media that were not modeled upon ocular perception. An example was James Watt’s indicator diagram of 1796. A gauge attached to a steam engine physically translated the pressure in a cylinder into an inscriptional graph of volume versus pressure. These instruments translated a world not visible by the unaided senses into “self-illustrating phenomena.” They produced visual media that were abstractions of physical processes. And ever-increasing amounts of background knowledge and assumptions were required to “read off” the invisible processes. They “showed” results, but through nonmimetic transformation.

Developing from the earliest diagrams of William Playfair and Johann Lambert, graphs, charts, and other visualizations, so common now to scientific endeavor, retain little physiognomic or iconic relationship to their subject matter. Instead, these visual media enable cognitive work to be performed. They have become cognitive prostheses rather than visual analogs for the world around us (Hankins and Silverman 1995; Tversky 1999). Visual media help us think and work as tools. They only “represent” in a very loose and often highly abstract manner. In step with the increased sophistication of instrumentation, our capacity for “intervention” comes to be the epistemic guarantor of our results.

Consequently, visual media are valued for their indispensable role in making modern science work (Carusi, Hoel, Webmoor, and Woolgar in press; Latour 1999; Lynch and Woolgar 1990). Emphasis has shifted away from debating whether information conveyed visually corresponds to the world toward information design and effectively expressing research with specific modes of engaging that information in mind (Tufte 1997, 2001). Correspondence is a difficult road to take with archaeology’s visual media. It robs media of their active role, begs wearisome epistemological questions, and encourages a passive “past voyeurism” on the part of the public. Media, it cannot be overemphasized, are far from mirror copies.

Walter Scott (1771–1832) was a magistrate, antiquarian, musicologist, novelist, essayist, collector, landowner, poet, best-selling author in the new book trade of the early nineteenth century, and inventor of the historical novel. His focus was the borderland between Scotland and England, between past and present. The two volumes of his Border Antiquities of England and Scotland (1814), profusely and wonderfully illustrated with engravings in classic picturesque style, are subtitled “Comprising Specimens of Architecture and Sculpture, and other vestiges of former ages, accompanied by descriptions. Together with Illustrations of remarkable incidents in Border History and tradition, and Original Poetry.” The work is a gazetteer of archaeological interests.

A long introduction takes the reader through a historical narrative of the Scottish border. On pages xviii–xix, Scott deals with the Roman frontier and Hadrian’s Wall: “The most entire part of this celebrated monument, which is now, owing to the progress of improvement and enclosure, subjected to constant dilapidation, is to be found at a place called Glenwhelt, in the neighbourhood of Gilsland Spaw.”

He adds a footnote:

Its height may be guessed from the following characteristic anecdote of the late Mr. Joseph Ritson, whose zeal for accuracy was so marked a feature in his investigations. That eminent antiquary, upon an excursion to Scotland, favoured the author with a visit. The wall was mentioned; and Mr. Ritson, who had been misinformed by some ignorant person at Hexham, was disposed strongly to dispute that any reliques of it yet remained. The author mentioned the place in the text, and said that there was as much of it standing as would break the neck of Mr. Ritson’s informer were he to fall from it. Of this careless and metaphorical expression Mr. Ritson failed not to make a memorandum, and afterwards wrote to the author, that he had visited the place with the express purpose of jumping down from the wall in order to confute what he supposed a hyperbole. But he added, that, though not yet satisfied that it was quite high enough to break a man’s neck, it was of elevation sufficient to render the experiment very dangerous. (Scott 1814, xviii–xix)

Was it that Ritson, a noted literary antiquarian, hadn’t read the many accounts of the Wall published since the sixteenth century in that fascinating lost genre chorography? Unlikely. Had he forgotten? Or was it rather, as Scott suggests, that his “zeal for accuracy” meant he had to visit and witness the very structure in order to authenticate the written accounts of the remains? He clearly assumes that there was or had been a Wall: ancient authors and sources document it. What he disputes is that there is anything left. This tension between text and monument is very characteristic of antiquarian debate, and Ritson was renowned for his skepticism regarding claims for the authenticity of ancient manuscripts and historical documents.

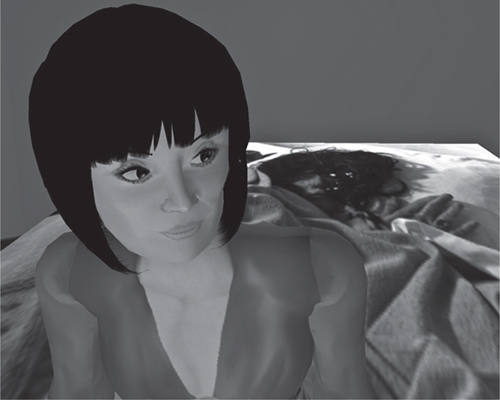

Alexander Gordon’s Itinerarium Septentrionale: Or, A Journey Thro’ Most of the Counties of Scotland, and Those in the North of England was published through private subscription in 1726. It deals with Roman remains in the north and describes the surviving remains of Hadrian’s Wall in great detail. Ritson may not have read it. He may have known it, but still doubted the description of Hadrian’s Wall. We may assume that Scott had read it: his copy is still in his library at Abbotsford (fig. 5.2).

Gordon literally paces out and records every boot-marked trace of the Wall in his itinerary. He might not have jumped off the Wall, but you can almost hear every crunch of his boots through the pages of his expensive folio.

The book sets the “northern journey” in the context of accounts in ancient texts of the Romans in the north. Gordon knows his classical authors. The engravings are revealing. He illustrates many rectangular monuments in their various relationships with straight Roman roads. The monuments are all unexcavated and simply comprise earthen features—tumbled-down, overgrown ramparts. Gordon’s illustrations mark out nothing except rectangles and lines; though they have, significantly, been paced out. The engravings of sculpture show only sketched-in figures, focusing instead on the transcription of the inscribed text.

FIGURE 5.2. Page 73 from Alexander Gordon’s Itinerarium Septentrionale: Or, A Journey Thro’ Most of the Counties of Scotland, and Those in the North of England.

Ancient authors, epigraphy, and the antiquarian’s boot—the topic here is the fidelity and authenticity of different kinds of witnessing of antiquity and its relics. This witnessing, representation, if you like, is in an indeterminate and debatable relationship to voice, text, image, and figure.

Scott’s own writing represents a miscellany of voices articulating past and present. His bibliography includes: ethnomusicological collection of medieval bardic epic poetry; his own poetry; medieval historical novels (most notably Ivanhoe); the antiquarian gazetteer; historical novels dealing with Scottish themes in recent memory (such as Waverley and Guy Mannering); essays and nonfiction in various genres. Many of these were illustrated with the latest in steel engravings.

Scott consistently elides fact and fiction in his examination of traces in the present of the past (archaeological, memory, textual, toponyms, landscapes). Establishing the authentic voice of the past was a recurrent theme in literary antiquarianism in the eighteenth century, ranging from Thomas Percy’s Reliques of Ancient English Poetry, an edited collection of antiquarian manuscript sources, to James Macpherson’s creation of the wholly fictitious medieval bard Ossian (see Stewart 1994 for a fascinating treatment of this issue). A related interest is the transition from voice (oral poetry, verbal account, memory) to text (a new version of the old song, the annotated transcription/edition, the historical novel, historical narrative). A similar concern is evident in the efforts to relocate and translate experiences of ruins, monuments, and land authentically into the illustrated book—how the witnessing pace of the antiquarian, how sites and their names, how place-events become itinerary, chorography, cartography, or travelogue.

Conventional notions of media (as material modes of communication—print, painting, engraving, or as organizational/institutional forms—the media industries) are of limited help in understanding what Scott and his contemporaries were up to in mediating authorial voice and authentic traces of the past. We can consider the rise of cheaper engraved illustration, the popularity of the historical novel in the growth of the publishing industry, developments in cartographic techniques and instruments. But in order to understand how all this and more came to be archaeology—the field, social, and laboratory science—we need to rethink the concept of medium.

Scott, Ritson, Gordon, and their like are making manifest the past (or, crucially, are aiming to allow the past to manifest itself) in its traces through practices and performances (writing, corresponding, visiting, touring, mapping, pacing, debating), artifacts (letter, notebook, manuscript, printed book, pamphlet, map, plan, plaster cast, model), instruments (pen, paint brushes, rule, Claude Glass, camera lucida, surveying instruments, boots, wheeled transport, spades, shovels, buckets), systems and standards (taxonomy, itinerary, grid), authorized algorithms (the new philology, legal witnessing), dreams and design (of an old Scotland, of a nation’s identity, of personal achievement). Making manifest came through manifold articulations. And “manifestation” was a complement to epistemological and ontological interest—getting to know the past “as it was, and is.”

Visual media, in the conventional sense (print, engravings, maps), are involved, but also much more that challenges the premises of communication and representation underlying the concept of medium. What we are seeing, we suggest, is a reworking of ways of engaging with place, memory (forever lost, still in mind, to be recalled), history and time (historiography, decay, narrative), and artifacts (found and collected). The author’s voice was being questioned and challenged. Who wrote the border ballads? Is this our history? Whom do you trust in their accounting for the past? Rational agricultural improvement was altering the traditional qualities of the land and ownership of land and property, which was being reinvented as landscape. The status of manufactured goods was changing rapidly in an industrialized northern Europe. That dinner with Ritson and the visit to Gilsland are establishing what constitutes an appropriate way of engaging with the past. It is only later on that Scott gets called a historical novelist, Ritson is marginalized as an irascible literary antiquarian, largely forgotten, and archaeology becomes the rationalized engagement with site and artifact through controlled observation, “fieldwork,” and publication in standardized media and genres.

In this discourse over appropriate ways of engaging with the past, medium is better thought of as mode of engagement—a way of articulating people and artifacts, senses and aspirations, and all the associative chains and genealogical tracks that mistakenly get treated as historical and sociopolitical context. Scott presents us with a fascinating laboratory of such modes of engagement, one that runs from field science to romantic fiction through to what was to be later formalized as Altertumswissenschaft by German classical philology.

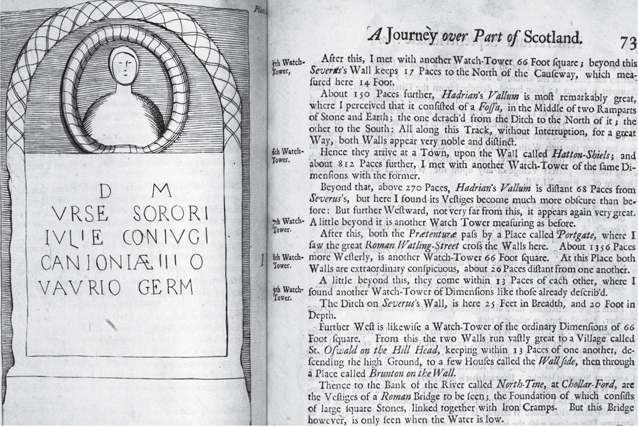

To recover the roles of media in archaeological work, let us now take a much closer look at a well-known example of archaeological surface survey and mapping. The aim of the Teotihuacan Mapping Project (TMP; fig. 5.3), begun in 1962 under the directorship of René Millon, was to provide the first complete map of Mesoamerica’s first city, the entire area of which covered some twenty square kilometers. It was a prodigious effort, mobilizing a panoply of productive forces to transform the monumental ruin into media. The “TMP map” has become the media architecture for all subsequent research at the well-known site, and it anchors a rich and lively “heritage ecology” at the site today (Webmoor 2007a, 2008 and 2012a). To exhume how this influential piece of media became stabilized as the standard, and to unpack and clarify what we mean by transformation, we need to be utterly specific. We have to go back to April of 1962 (and again to September 1962).

Compañía Mexicana Aerofoto, subcontracted by Hunting Mapping of Toronto, flew over Teotihuacan and took photographs using a Wild RC5A high-precision aerial surveying camera with distortion-free lens and a six-inch focal length. From 4,000 feet above the ground, the flight led to the generation of photographs at a scale of roughly 1:8000. These images would form the basis for photogrammetric drawings.

FIGURE 5.3. Teotihuacan Mapping Project with satellite imagery and modern pueblos. From Millon, Drewitt, and Cowgill 1973.

There were two stages to transforming the aerial photographs into maps: (1) from photo to photogrammetric drawing and; (2) from photogrammetric drawing to map. The aerial photographs contained too much information and detail irrelevant to the final map of the site’s features, and in spite of all efforts on the part of the pilot and photographer, it could never be framed perfectly perpendicular to the ground surface. To reduce or to enable the identification of significant features and to compensate for oblique and irregular framing, ground control points were established at ten locations around Teotihuacan. These control points were located on the aerial photographs and the photographs were pierced with fine metal points. These metal points served to anchor the photographs to the ground. The 1:8000-scale photographs were transformed into glass plates. Cronaflex drafting film, which is dimensionally stable, was laid over the plates and permanent features of the site—architectural, natural, and modern infrastructural—were then penciled in. The Wild A8 stereo plotting instrument enabled the transformation of the glass plates into 1:2000 photogrametric drawings.

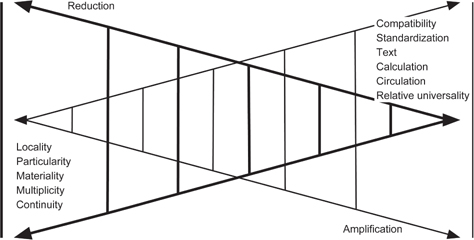

The mapping process moves from aerial perspective to photographs to glass plates to photogrammetric drawings, which were the basis for the TMP maps. Though many of those qualities apparent when walking the ruins of Teotihuacan have been lost—sounds, smells, textures, and kinetic experiences—much has been gained, especially when considered in terms of the project’s goals. Spatial dimensions, so necessary for mapping an architecturally complex site, have been made the focus. Maintaining tight control over the establishment of control points and scaled transposition of glass plate to photogrammetric drawing meant that the accuracy of the final map was roughly 2.5m on the ground and usually within 1.25m. Feature boundaries, the line of house walls, the edge of pit structures, the orientation of steps, waterways (the Río San Juan, rerouted early in Teotihuacan’s occupation, for instance), platforms, plaza dimensions, ancient roadways, and even, as a combination of all of these features, the directionality of the rigidly planned city are all particularly discernible. These properties of the ancient metropolis emerge against the backdrop of overgrowth and vegetation, crumbling walls and partially covered features, which superficially appear to dominate the photographs. The qualities of the site have been amplified, akin to the torqueing up (or down) of details, depending upon the scale of map or photograph. There is an obvious trade-off in moving thus far along this chain of transformation from one medium into another.

FIGURE 5.4. Circulating Reference. From Latour 1999, 70, 73.

Latour describes this entire process of moving across a series of small gaps as “circulating reference” (fig. 5.4). We no longer are talking of media mirroring nature, but rather of a heterogeneous set of instruments, actions, archaeologists, and others engaged in a series of coordinated operations articulated in order that the final map will do more than resemble the site: “it takes the place of the original situation” (Latour 1999, 67). It stands in for Teotihuacan so that it may be integrated with other information collected in the field—it must be fungible with graphical notation, statistical nomenclature, and textual narrative. Instead of a correspondence of the TMP map to the ruins of Teotihuacan, we have an actively manipulated transformation that holds something of the reality of the site and that may be circulated widely in order to be useful.

For practical use, the TMP personnel now have portable maps. These flat and mobile paper media are guides in predicting where other features and possible sites will be located and these may now be recorded and further mapped. Each step has transformed something of these visual qualities into a flat photograph, onto Cronaflex, and finally as paper.

In this movement, we have reduced Teotihuacan’s particularity, locality, materiality, multiplicity, continuity, and ambiguity; but we have amplified compatibility, standardization, text, calculation, circulation (Latour 1999, 71; see fig. 5.4). None of these transformative steps, moving from one mode of engagement to another, from one visual media to another, can be described as a process of mimetic correspondence or a series of mirror copies. Or, if copies, then there meaning comes something closer to “copious” as suggested by the original Latin root copia (Latour and Lowe 2011). The aerial photograph is not a copy of the site itself, and the photogrammetric drawing at a 1:2000 scale is not a copy of the aerial photograph. Of course, they are closely related. But it is how they are related that makes for their usefulness to the TMP personnel. Each step in moving from matter to media is aligned with what came before and what will come after. With the metal pins piercing the aerial photographs, this alignment is physically apparent. With other steps, the alignment may not be so evident, but each mediation is carefully designed so that if one so wished, we could move back and forth by connecting up references circulated as media. Placing such reference trails for our visual media to follow is a basic element of the ecology of archaeological practices. Datum points, the Universal Transverse Mercator system, GPS coordinates, and the labeling of excavation corners facilitate such referencing. We usually focus upon these references in order to be systematic and consistent, for relocating sites and, most important, for reasons of provenience. Our information, our data, would lose much of their value if they were not linked up with these circulating references; yet our encompassing visual media only work by containing these references so that they can be linked “across” this chain. We “dig square holes” (cf. Thomas and Kelly 2006, 128) for the ease of translation into media that are fungible, combinable, and traceable to help ensure that these “chains of reference” don’t break. Our work rests upon the traceability of this process, as does the question of accuracy (Latour 1986).

There is, however, still much more work to be done by the TMP crew (personnel, instruments, media, and supporting institutions) as they progress toward the two-volume, four-part compendium, containing over 147 maps (Millon 1973; Millon, Drewitt, and Cowgill 1973). The photogrammetric drawings based upon the planometric view of the site from 4,000 feet was tied to the ground of the site by physically substituting metal points piercing the aerial photos for the ground control points. It is so easy to overlook the seemingly mundane work that these unassuming pins do. Indeed, the task of superimposing images to the ground was delegated to these metal pins and, while they are absent in the final, flat map, it is these pins holding photo and drawing together that allow later sketches and locations obtained in the field to be placed on the map with the assurance of fidelity.

Following the precedent set while mapping the Maya city of Tikal, Millon chose to use a Cartesian grid-system comprised of 500m2 blocks (Millon 1973, 7). This divided up the large site into manageable units, allowing Teotihuacan to be partitioned into ever-smaller blocks. In this way, all subsequent depictions of the site, from 3D “fly-throughs” of a virtual La Ventilla apartment compound to the stratigraphic profile of a trench in the ciudadela, can be hung on the scaffolding provided by the TMP map. It is a media architecture built for future generations. At the same time, the map is fluid and extensible. It can roll its grid outward infinitely to cover macro features; conversely, it can fold the micro details of burial offerings deep within the pyramid of the moon into its sliding scale. These are mercurial, hermetic media at their best.

The map itself now came to structure further survey, mapping, and engagement with Teotihuacan. What was to be the orientation of the 500m2 grid? Looking at the 1:2000 photogrammetric drawings, Millon and the TMP crew could see that all of the structures of the pre-Hispanic city adhere to a citywide orientation (Millon 1993; Sugiyama 2005). This orientation was based upon quadrant dimensions, or more precisely a quincunx arrangement, accounting for the vertical dimension so important to Mesoamericans. With this orientation Teotihuacan North is approximately 15 degrees 25 minutes east of north. The crew chose the site’s central avenue (the avenida or calle de los muertos) to serve as the centerline of the grid system and map, and thus orient the map to Teotihuacan north. The centerline for the map grid was drawn down the middle of the axis of the avenida on the 1:2000 drawings.

With this basis for survey, team member Raymond Krotser returned to the avenida and took measurements between prominent structures that were clearly distinguishable on the 1:2000 drawings (Millon 1973, 12). With the measurements in hand, he then plotted to the distances to see how closely they approximated their location on the ground. Krotser selected a final sixteen points, spanning 2,300m from the Pyramid of the Moon at the far north to an abandoned modern restaurant at the far south. These were marked on the drawings, and George Cowgill drew a “best fit line” (1973, 12). This was the “center line” on the drawings. And once established with reference to the avenida, it could be readily inscribed on the ground with the aid of paint and concrete and steel piping.

White lines mark the centerline along the northern half of the site. To the south the TMP personnel placed 50-centimeter-long, half-inch galvanized steel pipes driven into holes 20–30 centimeters deep and surrounded by concrete. They needed to be substantial so that they could serve as reliable witnesses in the future. Unlike the fragile marks on the drawings, these final steel rods will continue to stand-in for the orientation and layout of the TMP map on the ground. Larger versions of the steel tacks piercing the aerial photos, they are now tracers of this work on the ground. They anchor the grid to the material world; this is the work of suturing. Much of the responsibility of guaranteeing the precision and accuracy of the TMP personnel and of the final map is transferred to these durable markers. Once set, new measurements, a comparison of scaled distances to real distances, angles and triangulation to other enduring features can all be performed again (and again).

Aligned as paint, steel rods, and the site’s architecture, with the centerlines of the primary axes in place, the 500m2 blocks, which will form the basic units of surface survey, can now be drawn in and labeled on the 1:2000 photogrammetric base map of the entire site (Millon 1973, 18). What normally is placed first in the sequence of archaeological survey—field reconnaissance, taking measurements, and drawings—is actually secondary to the series of transformations that have just followed. With the map now anchored to the site, the field crews can begin a controlled ground survey. The maps of the TMP do not stand for Teotihuacan; they stand in for the site and provide a basis for further work to take place.

In our example from Teotihuacan, we have directed attention away from the communicative and representational function of media. We are arguing for a more performative appreciation of archaeology as work done with the things of the past, productive labor directed often toward building knowledge of the past, where such knowledge is an achievement, not a discovery.

That the “archaeological record” of sites and remains is an outcome of archaeological practice rather than a datum seems now well established (Hodder 1999; Lucas 2001a and 2012; Patrik 1985; Schiffer 1978). Something of the past is held in ruins and remains, in its archaeological traces, assembled through engagements with avenues and stone platforms, as well as operations performed with instruments, archives, through networks of institutions, and, of course, visual media. In this archaeological work, representation and “accuracy” come second to the critical need to move back and forth, to retrace the connections between the material remains, the evidence, and their stand-ins or proxies, the texts and visuals. This stabilizes the past, however provisionally, through connecting a host of humans and nonhumans. The measure of media is therefore their ability to afford such movement, such engagement, and to what extent they afford the possibility of future action upon and engagement with the past (we take this up in the following chapter).

One way that media may do this, somewhat ironically, is that representation can provide closure upon a piece of research. A convincing rhetoric of text and image (Gross 1990), a marshaling of evidence and study, can “black box” research such that it can be taken as given, work can move on, at least until the matter is reopened (Latour 1987). One aspect of such rhetoric involves visual media being treated as illustration, that is, they may act primarily as visual supports for statements made in a text (Webmoor 2005); photographs of an excavation, for example, may affirm the statements made about the structure of the site, rather than provide evidence for debate (Shanks 1997).

As corollary to this appreciation of active media(tion), the way media work with archaeologists, the paradigm of the archaeologist as custodian or steward of the past has been under serious challenge for some time now. As in the eighteenth century, this challenge is to do with shifting definitions (legal included) of cultural property. Archaeologists are again having to address the political matter of re-presentation—that is, advocacy and witnessing, who is representing (in a constitutional as well as communicative sense) the past, for whom, and on what basis. That the past is there as a datum to be represented is under question; though, of course, the traces remain, conspicuously prompting these questions and participating in arriving at potential answers. In chapter 8, we further elaborate the “expressive fallacy,” introduced in chapter 2 above, that archaeological texts somehow “express” or represent the past. In chapter 6, we further consider these questions of manifestation in relation to memory practices and emergent digital technologies.

1. We might further consider these points with respect to the figures behind the tradition of British empiricism. Francis Bacon and John Locke were distrustful of these instruments and the visual rhetoric that they produced (Hankins and Silverman 1995).