Beef arid cheese cause a bigger insulin release than pasta, and fish produces a bigger insulin release than popcorn.

Beef arid cheese cause a bigger insulin release than pasta, and fish produces a bigger insulin release than popcorn.5

The Sizzle:

The Meat Seduction

The sizzle of a steak can be the quintessence of allure. Burgers on the grill, roast chicken, a tantalizing holiday turkey, a fish filet smothered in tartar sauce—for many people, they are more mouth-watering than just about anything else. They may hold enough cholesterol to sink a ship, health organizations might plead with us for moderation, and cartoonists may mock our meat habit—”You want chemotherapy with that?” the butcher asks—but even so, it’s hard to pry the steak knife from our meaty fists.

Most health authorities encourage people to limit how much meat they eat—or skip it entirely—and for good reason. More life-threatening illnesses have been linked to meat-based diets than to just about any other factor in our lifestyle or environment. Cancer, heart disease, diabetes, kidney problems, obesity, food-borne infections, and many other conditions are much more common among meat-eaters than among those who give meat a wide berth.1 And research teams have come a long way toward explaining why animal protein, animal fat, and cholesterol lead to these problems.

Meat aficionados have resisted such concerns, floating semi-scientific arguments favoring flesh-heavy diets, such as the Atkins Diet. Their arguments have not held up very well, as we will see. But the fact remains that once people get hooked on meat, they want to stay hooked. As we saw in the first chapter, fast-food chains pushing burgers and fried chicken in Asia found an almost immediate following, despite the fact that the arrival of Western eating habits brought weight problems, heart disease, and cancer rates that were previously unknown.

I recently took a plane from Los Angeles back home to Washington, D.C. As the lunch cart arrived, the man and woman seated next to me chose beef over the pasta dish. As the conversation turned to food, it was clear she was worried about him. He had had a stent put in his heart to prop open a coronary artery. But he hadn’t changed his diet—in fact, his doctor had not offered any diet advice at all—and a recurrence of heart problems loomed before them. He did not exercise. Although they were both in their sixties, this was a fairly recent marriage, and she was afraid that her beau was not taking care of himself.

He had heard the arguments about cutting back on meat and was quite willing to believe that a diet change would help him. But he couldn’t imagine a meatless meal being satisfying. Nonalcoholic beer or decaffeinated coffee might be tolerable. But life without good food just wasn’t worth living.

However, a coast-to-coast flight lasts a good five hours. And that’s more than enough time to think things through a bit more. Before we get back to this couple, let’s take a look at what is really at the heart of the matter.

Is Meat Addicting?

Many children don’t take to meat right off. As infants and toddlers begin to taste solid foods, they like fruit and rice cereal instantly. But they often resist meat, as if Mom had offered them a beer or a cigarette. Before long, however, they will become habituated to it, and it can then develop into a very persistent habit. An April 2000 survey of 1,244 adults revealed that about one in four Americans wouldn’t give up meat for a week even if they were paid a thousand dollars to do it. People from Asian and Hispanic backgrounds were more willing to accept the hypothetical offer (fewer than 10 percent turned it down), presumably because meatless choices are major parts of their traditional cuisines. But black and white Americans were more reluctant, with 24 percent of whites and 29 percent of blacks absolutely unwilling to swap meat for cash. Cholesterol, fat, salmonella, E. coli, Mad Cow disease, and foot-and-mouth disease may come and go in the public’s mind, yet meat eating goes on.

Why such enthusiasm over meat? After all, nature designed animals’ muscle tissues to help them move their legs, flap their wings, or wiggle their tails, not as a nutritional supplement.

Well, for starters, an attraction to any fatty food makes some biological sense. Fat happens to be the most calorie-dense part of any food we eat (fat has nine calories in every gram, compared to only four for carbohydrate or protein.) Presumably, as our species evolved, those people who knew a calorie when they saw one—that is, those who were attracted to fattier foods—would be more likely to survive in times of scarcity. If that taste for fat leads us to the occasional nut, seed, or olive, no harm is done. But nature never figured that this same attraction would lead us to prefer hamburgers, fried chicken, and other dangerously fatty, high-cholesterol foods. When you look at what meat is made of, anywhere from about 20 to 70 percent of its calories come from pure fat.

The taste for meat may be similar to the taste for french fries, onion rings, or anything else with a lot of fat in it—that is, it is due to evolutionary pressures leading us to prefer high-calorie foods. And there is also a role for the simple force of habit. Scientists believe that, once we get used to fatty foods as a result of their being on our plate day after day, we come to prefer them and tend to seek them out.

But there may be another side to the meat habit. Scientific tests suggest that meat may have subtle druglike qualities, just as sugar and chocolate do. When researchers use the drug naloxone to block opiate receptors in volunteers, meat loses some of its appeal. Researchers in Edinburgh, Scotland, found that blocking meat’s opiate effect cut the appetite for ham by 10 percent, knocked out the desire for salami by about 25 percent, and cut tuna consumption by nearly half.2 They found much the same thing for cheese, by the way, which will not surprise you, considering cheese’s cocktail of opiates we looked at in the previous chapter.

What appears to be happening is that, as meat touches your tongue, opiates are released in the brain, rewarding you—rightly or wrongly—for your calorie-dense food choice and propelling you toward making it a habit.

And scientists are examining another part of the addiction puzzle. It turns out that meat stimulates a surprisingly strong release of insulin, just as a cookie or bread does, a fact that surprised nutrition researchers. In turn, insulin is involved in the release of dopamine between brain cells. Dopamine, as you’ll recall from chapter 1, is the ultimate feel-good chemical turned on by every single drug of abuse—opiates, nicotine, cocaine, alcohol, amphetamines, and everything else. Dopamine is what powers the brain’s pleasure center.

Now, the fact that meat stimulates insulin release is foreign to people who think of insulin as relating only to carbohydrates. The idea is that carbohydrates—sugary or starchy foods—break apart into natural sugar molecules during the process of digestion, and, as these sugar molecules pass into the bloodstream they spark the release of insulin, the hormone that escorts sugar into the cells of the body. True enough. But protein stimulates insulin release, too. In research studies, researchers feed various foods to volunteers, and then take blood samples every fifteen minutes over the next two hours. Meat causes a distinct, sometimes surprising, insulin spike. In fact, beef and cheese cause a bigger insulin release than pasta, and fish produces a bigger insulin release than popcorn.3

Researchers are only beginning to unravel the interplay between insulin and addictions. They have been intrigued by occasional case studies of patients who require insulin to treat diabetes surreptitiously upping their doses, and evidence that insulin function is altered in opiate addicts. Stay tuned.

The good news is that, once a meat habit has been decidedly broken for a few weeks it fades from memory surprisingly easily. Both in our study of Dr. Dean Ornish’s heart patients and in our later studies, including a study of women aiming to lose weight, few people reported any continuing desire for meat once they had left the habit behind. They could have it if they wanted, but it no longer controlled them. Many described it the way reformed smokers think of tobacco—as something they were glad to be rid of.

Meanwhile, back at 37,000 feet, my fellow air passengers asked about how people actually break a meat habit. “I just don’t think I could do it,” he said. “It’s hard to imagine.” I reassured him: “You shouldn’t do it—that is, not at first. The first step, before you take anything out of your diet, is to bring in new foods. There are probably plenty of meals you like already that have no meat in them at all.” We thought through our list: spaghetti with tomato sauce and fresh basil, vegetable stew, split pea soup. Chili could be made without meat and still be very tasty. All the vegetable curry dishes are great. Mexican food—bean burritos with spicy salsa. They had not yet tasted a veggie burger, but took it on faith that they might be up to snuff. Mushroom gravy might go well on a baked potato.

Beef arid cheese cause a bigger insulin release than pasta, and fish produces a bigger insulin release than popcorn.

Beef arid cheese cause a bigger insulin release than pasta, and fish produces a bigger insulin release than popcorn.

“Take your time and find the ones you really like,” I said. “Once you have plenty of good choices picked out and your kitchen shelves are stocked with healthy things to eat, then it’s time to make the break. But the trick is to do it for just three weeks.” The idea is that, if you set meat aside for three weeks, your tastes change. In the same way as people switching from whole milk to nonfat milk quickly come to prefer the nonfat variety—and can no longer stomach full-fat brands—when you lighten your whole diet, the same process occurs. It takes only about three weeks. If you do it really well and don’t cheat, your taste buds learn a new set of preferences. After three weeks you can decide whether to stick with it or not.

By the time we landed they were intrigued at the possibilities. He might just be able to tackle this heart problem after all. And the new menu was starting to sound pretty good. They could gain energy, get in shape, knock off a few pounds, and really enjoy their lives together.

Is It Good to Break a Meat Habit?

We’ve all heard hints that we might live longer or be a bit healthier if we set meat aside. It’s true. When you step away from the meat counter you do yourself a huge favor.

Preventing—and Reversing—Heart Disease

Perhaps the best-known advantage of breaking a meat habit is what it does for your heart. In 1990, Dr. Dean Ornish sparked a revolution in cardiology when he showed that a vegetarian diet, along with other healthy lifestyle changes, actually reopened blocked arteries in 82 percent of his research participants—without surgery and even without cholesterol-lowering drugs.4

Heart disease typically starts with fat and cholesterol from meat and other animal products, which increase the amount of cholesterol in the bloodstream. Cholesterol particles then invade the artery wall, causing the formation of small bumps, called plaques, which strangle the flow of blood to the heart muscle. But setting aside animal products and keeping the fat content low in the foods you eat stops this process in its tracks.

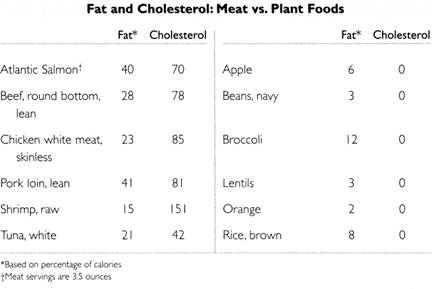

Now, chicken-and-fish diets are not low enough in fat or cholesterol to do what vegetarian diets can. Take a look at the numbers: The leanest beef is about 28 percent fat, as a percentage of calories. The leanest chicken is not much different, at about 23 percent fat. Fish vary, but all have cholesterol and more fat than is found in typical beans, vegetables, grains, and fruits, virtually all of which are well under 10 percent fat. So, while white-meat diets lower cholesterol levels by only about 5 percent,5 meatless diets have three to four times more cholesterol-lowering power, allowing the arteries to the heart to reopen.

Easy Weight Loss

Not only did Dr. Ornish’s patients reopen blocked arteries, they also lost weight—more than twenty pounds, on average, over the first year. PCRM’s studies of meatless diets have shown the same thing.6 While some people have tried to lose weight by leaving off their plates everything other than meat—using the Atkins Diet and similar approaches that ban bread, potatoes, pasta, beans, and every other shred of carbohydrate—an equally effective and far healthier method uses exactly the opposite approach, emphasizing grains, vegetables, fruits, and beans. Because meat and other fatty foods are, by far, the most concentrated source of calories, when they are off your plate your calorie intake naturally falls. So, even when people have about as many carb-rich foods as their appetites call for, the average weight loss is about one pound per week, week after week after week, even if they don’t count calories or limit portion size. More on this in a moment.

Preventing Alzheimer’s Disease

Recent studies have suggested that choosing foods that drive your cholesterol down might do more than prevent a heart attack. It might also cut your risk for Alzheimer’s disease. People who keep a low cholesterol level are at significantly less risk of the cognitive impairment as they age.7

And researchers have gone a step further and zeroed in on an amino acid—that is, a protein building block—that comes primarily from the breakdown of animal proteins. It is called homocysteine, and it appears to increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease.8 Cutting the amount of homocysteine in your bloodstream appears to cut the risk of the disease, and it is wonderfully easy to do. The keys are (1) to get your protein from plant sources, rather than animal sources, and (2) to have plenty of the vitamins that break homocysteine down—folic acid and vitamin B6 (from beans, vegetables, and fruits) and vitamin B12 (from fortified foods or supplements.)

Preventing Cancer

Breaking a meat habit cuts your overall cancer risk by about 40 percent.9 Your risk of colon cancer drops by about two-thirds, according to Harvard University studies including tens of thousands of women and men.10,11

In their search for the smoking gun linking meat to cancer, scientists have discovered cancer-causing chemicals, called heterocyclic amines that form as meat is cooked. And the issue does not stop at red meat. While these carcinogens are often present in well-done beef, they have turned up in far higher levels in grilled chicken, as well as in fish.12 The good news is that meatless meals—whether it’s pasta marinara, vegetable curry, spinach lasagne, or anything else—are generally free of these problem compounds and are rich in nutrients that protect against cancer.

As meat is cooked, cancer-causing chemicals, called heterocyclic amines, form within the meat tissues.

As meat is cooked, cancer-causing chemicals, called heterocyclic amines, form within the meat tissues.

Preventing Osteoporosis

When you get your protein from plant sources instead of animal products, your bones breathe a sigh of relief. Here’s why: Animal proteins are high in what are called sulfur-containing amino acids.13 These acidic protein-building blocks tend to leach calcium from the bones, and that calcium passes through the kidneys and into the urine.14,15 Plant proteins are far more healthful. While still containing all the essential amino acids you need for building and repairing body tissues, they are far lower in sulfur-containing amino acids, and they help protect your bones.

A Cleaner Food Supply

Many people have turned from red meat to fish, encouraged by reports that fish contains “good fats.” However, those “good fats” are just as fattening as any other kind of fat, as the native populations of Arctic regions have demonstrated. People chowing down on salmon are likely to store a fair amount of “good fats” all around their middles and up and down their thighs.

Perhaps worst of all, fish is by far the most contaminated food. As environmental experts monitor chemical contamination in fish, they routinely issue advisories, such as one from Virginia’s Department of Environmental Quality, which recently pointed out that catfish and carp had PCBs up to 3,212 parts per billion, more than five times the allowable limit. PCBs, or polychlorinated biphenyls, are chemicals that were used in electrical equipment, hydraulic fluid, and carbonless carbon paper. They linger in waterways and, like mercury and other contaminants, flow through fish gills, lodge in fish muscle tissues, and routinely show up in governmental tests. Because fish migrate and water currents spread chemicals from place to place, such contamination is now ubiquitous. Air currents carry mercury from power plants and waste incinerators to water sheds hundreds or even thousands of miles away, and the metal ends up in tuna and other fish as a matter of routine.

When it comes to thinking about healthy foods, many of us tend to focus on one problem at a time. When news reports carry alerts about chemical contaminants, we switch from fish to chicken or beef. When salmonella and E. coli hit the headlines, we quit eating chicken and beef and rush back to fish. Happily, there are plenty of healthful foods that skip all these problems. More on this in part III.

Meat Strikes Back: The Atkins Diet

On July 7, 2002, The New York Times Magazine published a huge cover photo of a greasy T-bone steak. The cover story, entitled “What if Fat Doesn’t Make You Fat?” rose to the defense of steaks, chops, and fried chicken, while striking out at the scientists and public health officials who counsel against fatty, meaty diets. Meat doesn’t make you fat, the article wanted readers to believe. It might even do the opposite. Wrapped up as the Atkins Diet, meat was offered as the centerpiece of a weight-loss plan that, the article went on, had now gained a sort of scientific respectability.

Apparently, the article was exactly the signal a meat-hungry nation was waiting for. Many people were all too glad to accept the idea that meat could actually help them lose weight, just as they had hoped for fen-phen, amphetamines, cabbage soup, ab-trainers, and just about every other dangerous or useless would-be remedy. The media went crazy with the story. Every newspaper in the country ran headlines saying beef and pork might be healthy after all, and evening talk shows had serious-sounding debates on the subject. Office water-cooler conversations pondered the “real truth” about meat, as if tens of thousands of scientific journal pages linking meat to illness were suddenly and miraculously erased, exonerating meat once and for all.

Because I imagine some readers have gone a little way down this same road, we should take a bit of time to understand a few things about the meaty, high-protein diets that win on-again, off-again popularity.

First, here is the idea behind high-protein diets: The human body naturally gets its energy from carbohydrate—the starchy part of beans, vegetables, potatoes, bread, and so forth. During digestion, carbohydrates break up into sugar molecules that power your brain and other organs. The Atkins Diet and other high-protein, very-low-carbohydrate diets operate on the theory that if you cut out carbohydrate—which is 50-60 percent of what people normally eat in a day—your body will have no choice but to burn fat. That’s true enough, provided cutting carbs means that you take in fewer calories than before. If you don’t, it doesn’t work at all.

Despite occasional accounts of dramatic weight loss, the results most people actually achieve with high-protein diets are not much different than with any other weight-reduction diet. On average, they lose about a pound per week.16 This is about the same as is seen with any other low-calorie diet, or with low-fat, vegetarian diets.17 And, for many people the diet is tolerable only for so long. Sooner or later you will return to a normal calorie intake. All the lost weight returns, and you are right back where you started.

Almost. Unfortunately, while you were on the high-protein diet you consumed astronomical amounts of fat, protein, and cholesterol. Needless to say, that has doctors worried about the risk of colon cancer, heart disease, kidney damage, and osteoporosis, among other problems.

The August 2002 issue of the American Journal of Kidney Diseases reported what happened when ten healthy individuals were put on a low-carbohydrate, high-protein diet for six weeks under controlled conditions. They found exactly what they feared—urinary calcium losses increased 55 percent, showing that the risks of bone loss, kidney stones, and kidney damage are not simply theoretical.18

Some high-protein diet advocates have gone to great lengths to try to make these problems disappear. When diet-book author Robert Atkins himself had a cardiac arrest at breakfast in 2002, news reports dutifully parroted the high-protein school’s suggestion that fat in his diet had nothing to do with the unfortunate event.

Meaty diets are also based on several nutritional myths. The first, which was the basis of The New York Times Magazine article, was that fatty foods must not be fattening, because fat intake supposedly fell during the 1980s, just as America’s obesity epidemic began. Ergo, fatty foods are not the culprit. The notion was that Americans had suddenly begun to shun fatty foods and had turned instead to fat-free cookies and low-fat foods of all kinds, so these new-fangled defatted foods must be to blame.

The truth, however, is clear from food surveys conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics. During the period from 1980 to 1991, daily per capita fat intake did not drop one iota. The number of trips to the golden arches and KFC did not dwindle in the least. While the American public added sodas and other sugary and starchy foods to the diet, forcing the percentage of calories from fat to decline slightly, the actual amount of fat in the American diet held steady as a rock.

The second myth was that people who eat the most carbohydrates tend to gain the most weight. In fact, the reverse is true. Many people throughout Asia consume large amounts of carbohydrate in the form of rice, noodles, and vegetables and generally have lower body weights than Americans—including Asian Americans—who eat large amounts of meat, dairy products, and fried foods. Similarly, vegetarians who generally follow diets rich in carbohydrates typically have significantly lower body weights than omnivores. Of course, it is true that when people cut carbohydrate or anything else from their diets and do not replace the lost calories with other foods they are likely to lose some weight. But carbohydrates are clearly not the cause of the weight problems of the Western world.

The bottom line is that, no matter how you slice it, meaty diets are bad news for your health.

The Meat Pushers

In the 1890s, my grandfather moved from Kentucky to southern Illinois, where he set up a small farm. He raised cattle, horses, and the occasional sheep or goat, and grew corn and soybeans to feed them. He passed the farm on to his children and grandchildren. Over time, that small farm grew. A great many pounds of beef have been raised at Barnard Stock Farms. And in recent years the farming business has changed beyond recognition. Across America and the rest of the world, farms have coalesced into huge agribusinesses.

When I was a boy visiting my farming relatives in southern Illinois, one of my uncles was complaining about government welfare programs. A big waste of tax money, he felt. His brother Lloyd, a minister, gently reminded him that he never seemed to complain when farmers got their government checks. What he meant, of course, was that farmers have been the recipients of enormous government programs.

They certainly have. In the 2001–2002 school year, the federal government bought up more than $200 million worth of beef, aiming to shore up farm profits. The beef ends up in school lunches and other programs. And, on September 9, 2002, Secretary of Agriculture Ann Veneman announced another purchase, this one for $30 million worth of pork, which soon ended up on school lunch trays. It’s not that our government imagined that America’s ever-fatter children needed more burgers or pork chops. Rather, school lunch purchases and other massive food-buying programs are designed to put dollars into farmers’ pockets. They pay scant attention to the foods children really need for health.

Federally managed programs run meat advertising, just as they do for dairy products. “Beef, it’s what’s for dinner,” “Pork, the other white meat,” and other common slogans are government programs. In turn, farming organizations are generous donors to political campaigns, making sure that nothing changes.

The meat industry has kept as tight a rein on government nutrition guidelines. When the USDA released its “Eating Right Pyramid” in 1991, cattlemen took umbrage at the design. Meat was suddenly less prominent than vegetables, fruits, and grains. So a battalion of angry farmers stormed over to the office of the Secretary of Agriculture, who promptly agreed to send the Pyramid back to the drawing board. However, even the meat industry’s influence was not sufficient to make meat trump vegetables and fruits for long, and the Pyramid was re-released more or less unchanged the following year.

The meat industry has done its best to control not only what goes into your mouth, but also what you think about good nutrition. It has been a loyal backer of the American Dietetic Association, sponsoring informational materials, dinners, and convention meetings. It has played the same game with the American Medical Association. When the AMA released its “videoclinic” on what doctors need to know about cholesterol, its sponsors were none other than the National Livestock and Meat Board, Beef Board, and Pork Board.

In the 2001–2002 school year; the federal government bought up more than $200 million worth of beef for school lunches and other purposes.

In the 2001–2002 school year; the federal government bought up more than $200 million worth of beef for school lunches and other purposes.

Enough of the bad news. The good news is that supermarkets now carry an enormous range of products that substitute for meat, from soy hot dogs and veggie burgers to faux Canadian bacon and ground beef substitutes. And a great many foods provide protein, iron, and other nutrients without fat and cholesterol, as we will see in the menu and recipe section.

It is indeed possible to break the meat habit and reap enormous health benefits, as Dean Ornish, M.D., proved in his research, and as I’ve seen, not only in our research participants, but even in my own family. When my father—who grew up with tremendous respect for his hard-working family and the livestock business they had built over many decades—developed a taste for vegetarian foods, I knew that anybody can break a meat habit.

The Bottom Line

• Many people are hooked on meat. One in four Americans would not give it up for a single week—even if they were paid a thousand dollars to do so. The habit is aggressively spreading to other countries—especially in Asia—that traditionally had plant-based diets. In its wake, overweight, heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and other health problems have become epidemics.

• The biochemical reasons behind meat’s ability to keep people hooked appear to be related to its high fat content, an apparent opiate effect, and perhaps its ability to spark the release of insulin.

• A switch from red to white meat does not help. Even without the skin, chicken has nearly as much cholesterol and fat as typical lean beef. While some people imagine that the fats in fish are “good” fats, anywhere from 15 to 30 percent of fish fat turns out to be nothing but artery-clogging saturated fat, and fish is easily one of the most chemically contaminated foods people eat.

• Breaking a meat habit brings a huge payoff. In research studies, people who choose meatless foods lose weight very easily. Their cholesterol levels fall, often dramatically, and diabetes, hypertension, and other health problems typically improve or even disappear.

• The U.S. government collaborates with industry to aggressively advertise meat products. When meat prices fall, the government buys up millions of dollars worth and puts it into school lunches and other programs.

• If you’re ready to break free, part II will get you started. There are so many enormously tasty replacements, as you’ll see in the menu and recipe section, you’ll wish you’d made the switch long ago.