§14 The Death That Brings Life (Rom. 6:1–14)

In Romans 6 we note a shift in the argument. The quotation from Habakkuk 2:4 in Romans 1:17, literally translated, “The one who is righteous by faith will live,” provided Paul with a general outline for the epistle. Until now his primary concern has been with the first part of the quotation, “The one who is righteous by faith.” But being right with God is not the end of the matter. Chapter 6 evinces that righteousness is a commencement, not a commemoration; reveille, not taps. In chapters 6–7 Paul takes up the relationship of faith to the new life which it inaugurates, and thus broaches the final topic of the Habakkuk quotation (which he will further explore in chs. 12–15), “will live.” He shifts, theologically speaking, to “sanctification” (NIV holiness), a word appearing in 6:19 that denotes the new life that follows in the wake of justification by faith.

Sanctification, of course, is not a separate phase of Christian development. We consider childhood and adulthood as distinct stages of life, but we may not conceive of justification and sanctification in this manner. Sanctification is justification in action; indeed, it is “realized righteousness.” Sanctification is righteousness before the throne of God and in evidence in the world. Israel was commanded to “be holy because I, the Lord your God, am holy” (Lev. 19:2). Christians are privileged to be the vessels of grace in and for the world, and their call and ordination to be such indicates their inestimable worth in God’s eyes. Justification is the impetus of sanctification, and sanctification is the unfolding of justification. Without justification sanctification is cut off from its source of renewal and becomes moralistic; without sanctification justification is incomplete and remains speculative. “A [person] is saved by faith alone, but the faith that saves is not alone—it is followed by good works which prove the vitality of that faith” (B. Metzger, The New Testament: Its Background, Growth, and Content, p. 254).

The introduction of sanctification is signalled by a strategic use of the theme of death. In the fifth chapter Paul spoke five times of Christ’s death; in chapter 6 he speaks thirteen times of the believer’s death in Christ, again in the first person plural. Christ’s death is not only the means of our salvation, it is the pattern of our sanctification. In chapter 5 Christ dies for sinners; in chapter 6 believers themselves must die to sin. The ongoing importance of dying to sin is emphasized by sixteen references to sin in this chapter of twenty-three verses! Colossians speaks of “Christ who is your life” (Col. 3:4). In a most dramatic way Paul’s use of death—almost always, in fact, as “the act of dying”—weaves the new life in Christ to the death of Christ. The woof of the Christian life crisscrosses the warp of Christ’s death.

The discussion of sanctification, however, is not relegated to a theoretical plane. The apostle stands before the task of making intelligible and practical the theological megaliths of chapter 5. Chapters 6–7 are clearly a response to certain objections to Paul’s gospel, namely, that justification by faith encourages sin and denigrates the law. Paul shores up his gospel by answering three false conclusions, each delineated at 6:1, 6:15, and 7:7. First, he challenges the perverse notion that if grace increases with sin, why not sin all the more (6:1–14). He then confronts the objection that freedom from the law leads to moral anarchy (6:15–7:6). Finally, in a very existential argument, he dismisses the objection that if the law reveals sin—indeed incites it—the law itself must be evil (7:7–25).

6:1 / In 5:20 the apostle made a daring pronouncement: “where sin increased, grace increased all the more.” Without clarification this statement could lead (and often has) to antinomianism. Paul broached this problem back in 3:8, “Why not say—as we are being slanderously reported as saying and as some claim that we say—‘Let us do evil that good may result’?” He could not afford to discuss the problem then, but he cannot afford to dismiss it now.

What shall we say, then? Shall we go on sinning so that grace may increase? Heretofore the discussion of sin and redemption has been largely relegated to the past, but with this question Paul now focuses on the future. One wonders how many times the apostle had met this objection on the mission field. Barth’s calling the question a “pseudo-dialectical game” makes light of a genuine difficulty which repeatedly emerges in church history (Romans, p. 190). There is an undeniable (though perverse) logic to verse 1, especially to someone who does not appreciate the wonder of grace: if grace is given in proportion to sin, why not sin extravagantly? The greater the sin, the greater the grace! Put more respectably: if God has done everything for us, and if our efforts achieve nothing for salvation, why make the effort to live a good life? The issue at stake here lies at the root of Jesus’ breach with a common Pharisaic attitude which he exposed in the parable of the Pharisee and the tax collector (Luke 18:9–14). If a bad person receives justification before a good person, what is the value of the moral life?

The point of 5:20, however, as Luther rightly noted, was not “to excuse sin, but to glorify divine grace” (Epistle to the Romans, p. 83). The question of 6:1 reveals perhaps the greatest temptation the Christian faces, namely, to take advantage of grace. The rank sinner is not nearly so vulnerable to this temptation as is the Christian who is the beneficiary of grace. Who has not presumed on God’s grace? Paul understood the temptation, but he could not tolerate its motive. Whoever would remain in sin has forgotten that sin was the cause not only of Christ’s death, but of his own death (5:21). But Christ through his righteousness has bestowed life and hence overpowered sin. God’s grace is indeed freedom, but freedom from sin, not freedom for it. “You … were called to be free. But do not use your freedom to indulge the sinful nature” (Gal. 5:13; see also 1 Cor. 6:12; 10:23). Whoever sees in grace a pretext to get away with as much as possible is simply showing contempt for Christ who died for sin. The freedom created by grace leads not to license but to obedience. Obedience honors God’s boundless love and responds to that love in the freedom which love creates.

6:2 / Paul counters the rhetorical question of verse 1 with a categorical rejection, By no means! Christ came to free us from our vices, not to feed them. Another rhetorical question sums up the contrast between Adam and Christ in a principle which deflates the swollen error of verse 1. We died to sin; how can we live in it any longer? The death-to-sin theme will guide Paul’s discussion through verse 11. Adam (= humanity apart from grace) led humanity like a prisoner to the gallows. If in Adam life leads to death, in Christ the sequence is reversed: death leads to life (we died … we shall live). By faith Christians share Christ’s death and resurrection. Whoever dies is free from sin (v. 7). Conversely, whoever remains in sin remains in death. Thus, the question of verse 2 arrests the folly of verse 1. Justification (death) leads to sanctification (life); we must first be made right before we can be made good. In Galatians Paul expressed this truth thus:

I have been crucified with Christ and I no longer live, but Christ lives in me. The life I live in the body, I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me (2:20).

Paul’s language of death, burial, and resurrection (vv. 2, 4), here applied to believers, is reminiscent of an older confession in 1 Corinthians 15:3–4, “that Christ died for our sins, … that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day.” Paul thus welds the experience of believers to that of their Lord. But what is the meaning of, we died to sin? Rather than releasing its grip at conversion, sin usually tightens it, as Paul well knew. He admonishes his readers in verses 12–14 not to succumb to sin, and in chapter 7 he will confess his own struggle with sin. Had Paul said, “Let us die to sin,” we might take it as an appeal to the believer’s will and a call to ethical arms. But there is no hint here of imitating the example of Jesus or of a moral crusade for the virtuous life. Paul says categorically, we died. This is neither empty creedalism, nor implicit asceticism. It is an objective reference to Christ’s death and to the reality that in Christ’s death something decisive has happened to believers. When Christ died for sinners, sinners died in God’s sight. “One died for all,” said Paul, “and therefore all died” (2 Cor. 5:14). Christ’s death for us has broken the power of sin over us, as verse 11 attests, “count yourselves dead to sin but alive to God in Christ Jesus.” The strong Son of God has wasted the strong man’s house, to allude to Mark 3:27. Since Christ has broken the claim of sin over our existence, sin no longer determines our existence. Christians are like citizens who have been liberated from a long and oppressive dictatorship. Something has been done to them: the liberator has broken the power of tyranny.

6:3–4 / The believer as the recipient of the benefits of Christ’s death is reinforced by the reference to baptism in verse 3: we were baptized into Christ’s death. Mention of baptism, of course, is an explicit reference to the sacraments and presupposes the reality of the church. Paul knows of no faith that is not attested to publicly via the sacraments and corporately in the church. And neither did the early church, for in prefacing verse 3 with, Or don’t you know, Paul obviously appeals to accepted tradition before him. The phrase, into Christ Jesus, is an abbreviation of the traditional baptismal formula, “into the name of Christ Jesus” (e.g., Matt. 28:19). Like the phrase, “taken into account” (5:13 above), this phrase derives from the language of accounting, wherein believers are “entered upon Christ’s account,” so to speak. Elsewhere Paul says believers were baptized into Christ’s body, thus stressing the corporate nature of faith (1 Cor. 12:13), but here the idea is one of personal union with Christ.

In speaking of union with Christ it is improbable that Paul borrows either thought or language from the various mystery religions of his day. Whereas the mysteries stressed the initiates’ experience, Paul stresses God’s decisive act on behalf of believers that is both signified and assured by baptism. The word “forensic,” which we used earlier of Paul’s understanding of righteousness, also applies here, for Christ’s death and resurrection usher believers into a new condition. With God they stand on the ground of faith instead of wrath, and they are freed from the pull of sin and death. What happened to Jesus on the cross happens to believers in baptism. Baptism is a sign of participating in Christ’s death and resurrection, of “charging our lives to his account.” Neither mechanical (i.e., something which occurs apart from human involvement), nor magical (i.e., the manipulation of supernatural power), baptism is an act of faith wherein God communicates the effects of Christ’s death and resurrection to the receptive heart.

The train of thought continues in verse 4: we were buried with him. The metaphor proceeds from the act of dying to the fact of death. Baptism denotes the state of death in which the power and effects of sin are annulled. In addressing converts baptized as adults, Paul correlates the immersion of baptism to the burial of the dead, in which the old life has ceased and has been committed to a foreign element. This is not the death of Nothingness, however, which awaits the old Adam, but a necessary prelude to resurrection and life. “Unless a kernel of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it remains only a seed. But if it dies, it produces many seeds” (John 12:24; see 1 Cor. 15:36). When Paul speaks of the death of believers in relation to the death of Christ he is not suggesting some kind of cultic identification, but rather the fellowship of Christ with his own, in which Christ’s death and resurrection are made fruitful for the church.

Union with Christ recurs throughout 6:1–8 in waves of repetition. “[We] were baptized into Christ Jesus,” “[we] were baptized into his death” (v. 3), “we were … buried with him” (v. 4), “we have been united with him” (v. 5), “our old self was crucified with him” (v. 6), “we died with Christ,” “we will also live with him” (v. 8). Paul’s cup overflows with syn-compounds (meaning “with” or “together” in Greek). The new existence is never spoken of apart from Christ because the new existence is Christ. He is our life (Col. 3:4). In the Gospel of John Jesus says, “apart from me you can do nothing” (15:5). So too with Paul, the Christian life is not an isolated effort but a corporate existence linked inextricably with Christ.

Believers share Christ’s fate, including his tomb! Only thus can they share his resurrection. Christ’s resurrection is a precursor to our own, so that we too may live a new life. The Greek preserves a more concrete summons to the moral life, “so also let us walk in newness of life.” Christ’s resurrection is thus presented not to indulge the readers in dreams of future glory, but to exhort them to moral resolution here and now. To be sure, Christ’s resurrection is a prelude to believers’ resurrection at the endtime, but it bears fruit today by calling believers to moral regeneration and responsibility. The Christian life is not a new attitude or better philosophy, but the release of righteousness into everyday life in an inexorable movement, step-by-step, toward Christ-likeness.

6:5–7 / Continuing with the theme of death and resurrection, Paul changes the metaphor from baptism to horticulture. The word united comes from the Greek, symphytos, meaning “to grow together,” or perhaps “to graft onto.” The perfect tense, we have been united, encompasses everything from the point of conversion to the present hour. The image of growth implies that believers’ lives merge with Christ’s and take on his characteristics. If the word means, “to graft,” then the bond is closer yet: the ingrafted shoot, severed from its native stock, derives life from the new stock. The NIV renders verse 5 in balanced parallelism, omitting, however, a characteristic Pauline word. The Greek reads, “For if we have been united to the likeness of his death.” Dunn identifies “likeness” as “the form of transcendent reality perceptible to man” (Romans 1–8, pp. 316–17). This means that Christ’s death is not a vague and general reference for believers, but an exact pattern. The resurrection is, of course, an equal pattern, but the future tense of the verb, we will be united in his resurrection, means that its full realization awaits the future.

The same idea reemerges in verse 6 under the image of slavery. For we know suggests that the gospel provides an intellectually meaningful explanation of life. Our old self and the body of sin recall human nature apart from grace (5:12ff.). Noteworthy is the phrase, so that the body of sin might be done away with. In calling sin a body Paul implies that sin is not isolated offenses or aberrations, but a totality capable of sustaining its own existence. This phrase sheds an additional light on sin. In verse 2 the believer “died” to sin, and its power was cancelled and finished. Here, however, the old self must be crucified, which is a slow and agonizing form of death. The body of sin is not instantly wiped out but gradually done away with. Paul envisions a struggle, indeed a battle that confronts the believer throughout life. His metaphors of changing clothes in Colossians 3:9, or of the contest between flesh and spirit in Galatians 5:17ff., imply similar processes in overcoming sin.

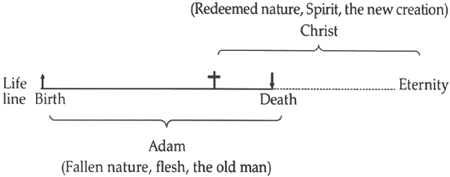

Authentic Christian existence always stands with one foot in the old life and one in the new. The Christian life is one of tension between Adam and Christ, sin and grace, flesh and spirit, death and life. Fallen human nature, which is with us from birth to death, pulls in one direction, and the regenerated life in Christ, which extends from conversion to eternity, pulls even more powerfully in the other. Christian life is hence life between the times and between two worlds: it is not yet free from the old nature, and not fully at home in the new. The following diagram may help to illustrate the dilemma:

The life of faith exists between conversion (†) and physical death (↓). If it is subjected to the fierce jealousy of the old life, it is worked upon even more by the upward pull of the new. In earthly existence the believer cannot escape fully the old Adam or inherit completely the new life in Christ. Paul himself knew this tension. Though the outer person is failing, the inner person is being renewed within us (2 Cor. 4:16). We are handed over to doubts, troubles, and death, but we are not annihilated. In the midst of “birth pangs” (Mark 13:8; 2 Cor. 4:7ff.; Gal. 4:19) we are born to faith, hope, and life eternal in God.

6:8–11 / The focus now shifts to Christ as the pioneer of the Christian experience. Paul endeavors to show that what is true of Christ is equally true for believers. Thus, if we died with Christ, we believe that we will also live with him (v. 8). Christian existence is not mechanical or automatic, like the law of gravity or the germination of a seed in springtime. In otherwise balanced statements Paul inserts, we believe, which means that believers live by the claim of faith, by the conviction of and commitment to God’s redemption of the world in Jesus Christ. For the present, faith believes more than it experiences, and thus it lives in hope, looking inevitably toward the future (we will also live with him) when Christ will be fully revealed. The wonder and reality of Christ’s death and resurrection can be realized only by a faith relationship with him who died and lives, Christ the Lord, the pioneer of salvation.

Faith is neither grounded in an illusion nor hitched to the cart of wishful thinking. We know that since Christ was raised from the dead, he cannot die again. Faith is grounded in the risen Christ who is witnessed to through the apostolic proclamation and who is present in the lives of believers through the indwelling of the Holy Spirit. The resurrection of Jesus Christ is the anchor of faith and the assurance of our future resurrection (1 Cor. 15:12ff.). Many religions believe in nature gods who, in accordance with the rhythm of nature, reappear in the cycles of death and renewal. This, however, is not the meaning of Christ’s resurrection, for his resurrection is unique, for death no longer has mastery over him (v. 9). The death and resurrection of Christ resound like a trumpet blast through the corridors of time—once for all. Not even the raising of Lazarus (John 11) is a prototype of Christ’s resurrection, for Lazarus died again. Jesus lived in perfect obedience to the eternal God. Because he lived for God he did not live for self; because he did not live for self he knew no sin; because he knew no sin death held no mastery over him. The cross swallows up the grave. Death can claim neither Christ again nor those who through faith “charge their lives to his account” and grow into his likeness.

Faith in the resurrected Christ is thus no pipe dream, but the fulcrum of history, the hope of the ages, the clarion truth that in Jesus eternity beams brightly into the dark shed of human history. Such a truth admits of no languid and nominal acceptance; a strain so rich pulls us from our seats to join the dance of life. The gospel is like the last train to freedom: it must be seized at all costs. “So also you,” says the original, “must count yourselves dead to sin but alive for ever more to God in Christ Jesus.”

6:12–14 / We now encounter the first moral exhortation in Romans! The cross and resurrection of Jesus have broken the power of sin, and believers at last stand before a real choice. They now have a fighting chance, for they can choose not to sin. Verses 12–14 hum with energy and urgency as Paul drafts believers into action. He shifts from the indicative to the imperative mood, and also from first person plural to second person plural. What God has done for believers at baptism is the indicative of grace; what God wills from believers as a consequence of grace is the imperative of ethics. The two are inseparable and witness to the unity of justification and sanctification. When a minister unites a couple in Christian marriage he or she enjoins them to make their vows actual, to become what they are. This is Paul’s appeal to the Romans. Christians are dead to sin, so let them henceforth live to God!

Sin is viewed as an armed tyrant who exacts obedience. But Christ has stopped sin’s despotic drive in its tracks. Because of Christ’s resurrection and assurance that God is for them, believers are now free. They are not to return abjectly to their gangster lord. Paul calls them to arms! Christians must not allow sin to reign unopposed in their lives, but, in the words of Cranfield, “revolt in the name of their rightful ruler, God” (Romans, vol. 1, pp. 316–17). These are the marching orders of a militant faith as Paul summons believers not to offer their bodies as “weapons” (instruments) of wickedness, but rather—as inmates on death row whose sentences have been pardoned—“to offer their parts … to God as instruments of righteousness” (v. 13). The Greek tenses of the verb offer are themselves instructive and might be paraphrased, “Do not continue offering yourselves to sin, but offer yourselves up once and for all to God.” The reference to parts (of your body) in verse 13 need not be limited to the physical body, for it surely includes in a figurative sense all human talents and abilities. The Christian life pictured in verse 13 is not an idealized watercolor but a bold (albeit simple) sketch of the rigors facing the faithful. The essence of the new life is not a concept or feeling detached from reality, but a trumpet call to active combat in the cause of righteousness against evil (Gal. 5:16ff.).

For sin shall not be your master, because you are not under law, but under grace, concludes Paul (v. 14). Since believers stand in grace, sin has neither the right nor the power to enslave them. Sin can rule only when it is obeyed, and Christ has broken its power. Sin need no longer be obeyed. Jesus said that no one can serve two masters (Matt. 6:24). Believers are like soldiers who have deserted the ranks of a rebel unit to rejoin their rightful leader: the orders of the rebel captain have no further authority over them. Death can no longer be Christ’s lord, and sin will no longer be the lord of the believer. The Lord of the believer is Christ. This, as we noted earlier, does not mean that sin has no power over believers, but that believers are not helpless in the face of sin’s assaults. They are free to rebel against it. Indeed, they are commanded to do so, empowered by grace, and guaranteed the ultimate triumph (8:37).

To be under grace instead of law is to be led by the Spirit (Gal. 5:18). The law makes sin known (3:20), whets one’s appetite for the forbidden (5:20), and hence leads to condemnation. The law is not thereby the opponent of grace, but its prelude (Gal. 3:24). The law demands righteousness, but cannot produce it, and those who try to fulfill it on their own become oppressed by its demands. To be under grace is to be free from the guilt of knowing the right but falling short of doing it. Grace means “that there is now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus” (8:1). It means that despite ourselves God is for us (8:31), God is faithful (2 Cor. 1:18), and God frees us for himself (Gal. 5:1).