Malibu Is Burning

A 1991 issue of differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies was one of the first major special issues of an academic journal on what guest editor Teresa de Lauretis called “queer theory.” For de Lauretis, queer theory generally emerged from academic studies of the construction of sexuality and of sexual marginalization: How have sexualities been variously conceived and materialized in multiple cultural locations? De Lauretis explains in her introduction to the volume that the conference leading to the special issue of differences (which convened at the University of California, Santa Cruz in February 1990) was also intended “to articulate the terms in which lesbian and gay sexualities may be understood and imaged as forms of resistance to cultural homogenization, counteracting dominant discourses with other constructions of the subject in culture” (iii). De Lauretis cites a few other conferences that had convened around the topic, but she implies in an endnote that queer theory is not much connected to queer activism: queers in the conference hall, at least for de Lauretis in 1991, didn’t have a lot to do with queers in the street.1

Obviously, even if the label “queer theory” itself emerged at a California conference in the early 1990s, this is only one of many origin stories, and one that might be contested in any number of ways by contemporary queer theorists.2 For my purposes in this chapter, I cite the example simply to provide an alternative myth for the birth of crip theory. If there is, or might be soon, something that could go by the name of crip theory, and even if it similarly has something to do with studying (in this case) how bodies and disabilities have been conceived and materialized in multiple cultural locations, and how they might be understood and imaged as forms of resistance to cultural homogenization, it also has a lot to do with self-identified crips in the street—taking sledgehammers to inaccessible curbs, chaining wheelchairs together in circles around buses or subway stations, demanding community-based services and facilities for independent or interdependent living. Although I have no problem with the idea that one path to coming out crip might be going to a conference or reading about it in a book (those are, after all, paths to identification or disidentification), in general the term “crip” and the theorizing as to how that term might function have so far been put forward more by crip artists and activists, in multiple locations outside the academy.3

Carrie Sandahl explains that crip (which, like queer, undeniably has a long history of pejorative use) “is fluid and ever-changing, claimed by those whom it did not originally define.” “The term crip,” Sandahl writes, “has expanded to include not only those with physical impairments but those with sensory or mental impairments as well. Though I have never heard a nondisabled person seriously claim to be crip (as heterosexuals have claimed to be queer), I would not be surprised by this practice. The fluidity of both terms makes it likely that their boundaries will dissolve” (“Queering the Crip” 27). In what follows, I build on Sandahl’s work in an attempt to imagine how crip theory might work, or what it might mean to come out crip.4

After a brief consideration of the term “crip” in the next section, I provide—in the remaining sections of the chapter—four meditations on coming out crip in various locations, including India, the United States, and South Africa. Situating the final meditation in southern California, however, I present it in two parts: the first (located in Malibu) is cautiously critical of a disability studies tendency to focus on the image apart from the space where the image and the (disability) identities associated with it are produced; the second (located in South Central Los Angeles) is attentive to various and local (crip) identities and practices that come into purview when the construction of identity is comprehended as a complex and contradictory process always taking place in specific locations.

Malibu in this chapter is both a literal location and—as the society of the spectacle would have it—a mythical site of arrival; those located in Malibu seemingly have it made and know who they are. South Central Los Angeles, in contrast, is a site of unmaking and dreams deferred. My consideration of South Central Los Angeles, perhaps unexpectedly, focuses on the Crips most famously associated with that location—young, African American men who are members of various Crip street gangs; I am concerned primarily with the ways in which disability functions in relation to their material reality and history. Both seemingly opposed snapshots of coming out crip in Malibu and Los Angeles, as well as the three snapshots that come before, locate human beings variously responding to neoliberalism and the condition of postmodernity. In my conclusion to this chapter, I weave these critical responses together and sketch out what might be understood as five principles of crip theory, before considering briefly a queercrip story that, in several senses, brings the urgency of crip theory home. That queercrip story is at least in part my own. Claiming disability is absolutely necessary for that story, but it is not and cannot be sufficient.

Although crip theory, as I sketch it out here and throughout this book, should be understood as having a similar contestatory relationship to disability studies and identity that queer theory has to LGBT studies and identity, crip theory does not—perhaps paradoxically—seek to dematerialize disability identity. This assertion can also be inverted: without discounting the generative role that identity has played in the disability rights movement, this chapter and book indeed attempt to crip disability studies, which entails taking seriously the critique of identity that has animated other progressive theoretical projects, most notably queer theory. The chunk of concrete dislodged by crip theorists in the street—simultaneously solid and disintegrated, fixed and displaced—might highlight these paradoxes. If from one perspective that chunk of concrete marks a material and seemingly insurmountable barrier, from another it marks the will to remake the material world. The curb cut, in turn, marks a necessary openness to the accessible public cultures we might yet inhabit.5Crip theory questions—or takes a sledgehammer to—that which has been concretized; it might, consequently, be comprehended as a curb cut into disability studies, and into critical theory more generally.

In many ways, the system of compulsory able-bodiedness I analyzed in the introduction militates against crip identifications and practices, even as it inevitably generates them. Certainly, disabled activists, artists, and others who have come out crip have done so in response to systemic able-bodied subordination and oppression. Stigmatized in and by a culture that will not or cannot accommodate their presence, crip performers (in several senses of the word and in many different performance venues, from the stage to the street to the conference hall) have proudly and collectively shaped stigmaphilic alternatives in, through, and around that abjection. At the same time, if the constraints of compulsory able-bodiedness push some politicized activists and artists with disabilities to come out crip, those constraints simultaneously keep many other disabled and nondisabled people from doing so.

Toward accessible public cultures: curb cut dislodged by disability activists. Courtesy of Division of Science and Medicine, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

Compulsory able-bodiedness makes the nondisabled claim to be crip that Sandahl tentatively imagines, in particular, unlikely for several reasons. First, a nondisabled person seriously making such a claim essentially disclaims (or refuses) the privileges that compulsory able-bodiedness grants to those closest to what Audre Lorde calls the “mythical norm” (Sister Outsider 116). This refusal has to be active and ongoing, functioning as more than a disavowal. In other words, nondisabled crips need to acknowledge that able-bodied privileges do not magically disappear simply because they are individually refused; the compulsions of compulsory able-bodiedness and the benefits that accrue to nondisabled people within that system are bigger than any individual’s seemingly voluntary refusal of them. Second, and related, a nondisabled person claiming to be crip dissents from the binary division of the world into able-bodied and disabled—or, rather, affirms the collective crip dissent from that division. Since dissent requires comprehending the able-bodied/disabled binary as nonnatural and hierarchical (or cultural and political) rather than self-evident and universal, and since the vast majority of both nondisabled and disabled people have in effect consented to comprehending that binary as natural, it is in some ways not likely that anyone would claim to be crip, but most especially those who are nondisabled.6 Third, even if nondisabled people engage such refusal and dissent, they risk appropriation, since the space for “tolerance” for people with disabilities that compulsory able-bodiedness and neoliberalism have generated can make nondisabled claims to be crip look like appropriation (and, indeed, nondisabled claims to be crip could quite easily function as appropriation). Attuned to some of the dangers of appropriation, liberal nondisabled allies might well be wary of identifying as crip, even if that wariness inadertently reinforces a patronizing tolerance.

As will become clear, however, in this chapter I argue in favor of unlikely identifications even as I attempt to guard against easy equations or oversimplified appropriations. Not only do I generate a critical space where certain nondisabled claims to be crip are more imaginable, I also read as crip some disabled actions and performances that may not always or explicitly deploy the term. My reasons for taking these risks can be traced, at least in part, to related risks taken in innumerable queer locations over the past few decades. In many ways, the late queer theorist Gloria Anzaldúa serves as a model for me in this risky project—in the context of this chapter she might be identified as the late crip theorist who was always adept at noting both how various progressive movements were congruent and how difficult it could be, nonetheless, to bridge the gaps between them. From one queer historical perspective, it is fortuitous that Anzaldúa writes, in This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, that “we are the queer groups, the people that don’t belong anywhere, not in the dominant world nor completely within our own respective cultures. Combined we cover so many oppressions. But the overwhelming oppression is the collective fact that we do not fit, and because we do not fit we are a threat” (“La Prieta” 209). Anzaldúa’s assertion, initially published in 1981, is fortuitous because her identification with and as “queer” could be said to authorize reading This Bridge Called My Back as an originary text for what would later be called queer theory (although many of the other contributors to the anthology express sentiments similar to Anzaldúa’s, most do so without calling those sentiments queer). Because the contributions of feminists of color are often far from central in the origin stories we construct for queer theory, Anzaldúa’s 1981 assertion is an important and ongoing challengeto the field or movement.7

From another perspective, however, for many readers, even if such passages were not in the anthology, This Bridge Called My Back would still be a queer production, given its timely intervention into a monolithic white feminism and its commitment to fluidity and oppositionality, to coalition and critique of institutionalized power, and (most important) to the generation of new subjectivities. Such interventions and commitments, after all, founded a great deal of queer theory and activism of the late 1980s and 1990s. As José Esteban Muñoz insists:

Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa’s 1981 anthology This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color is too often ignored or underplayed in genealogies of queer theory. Bridge represented a crucial break in gender studies discourse in which any naïve positioning of gender as the primary and singular node of difference within feminist theory and politics was irrevocably challenged. Today, feminists who insist on a unified feminist subject not organized around race, class, and sexuality do so at their own risk, or, more succinctly, do so in opposition to work such as Bridge. (21–22)

Muñoz goes on to place his own openly queer project, Disidentification: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics, in a direct line of descent from Moraga and Anzaldúa’s, as part of “the critical, cultural, and political legacy of This Bridge Called My Back” (22).8 For Muñoz, however, it is the range of identifications and disidentifications that This Bridge Called My Back makes possible, and not simply the volume’s occasional use of the term “queer” that makes it such a foundational text for queer theory. Because of how the text functions, in other words, Muñoz risks reading the volume as queer, even if it is rarely named as such and even if some contributors might have quarreled, in various contexts, with the term (as Anzaldúa later did, even while [re]deploying it).9

As far as I know, Anzaldúa herself never used the term “crip,” though following her death from complications due to diabetes, there have nonetheless been fledgling attempts to link her legacy to crip movements.10 Ultimately, for me, it is less Anzaldúa’s use or nonuse of crip that leads me to position her posthumously as a crip theorist and more her career-long consideration of terms and concepts that might, however contingently, function to bring together, even as they threaten to rip apart, los atravesados: “The squint-eyed, the perverse, the queer, the troublesome, the mongrel, the mulato, the half-breed, the half dead: in short, those who cross over, pass over, or go through the confines of the ‘normal’” (Borderlands/La Frontera 3). Anzaldúa’s famous theory of the borderlands, even as it is grounded in south Texas and centrally concerned with what she calls mestiza consciousness, has proven so generative for feminist, queer, and antiracist work because it simultaneously invites disparate groups to imagine themselves otherwise and to engage purposefully in the difficult work of bridge-building.

Anzaldúa may now be located on the other side of the most inexorable, overdetermined, or naturalized border—the border between the living and the dead—but that location should not preclude consideration of how she might continue to speak with crip theory, or even as a crip theorist.11 Placing Anzaldúa’s assertion that “we are the queer groups.… and because we do not fit we are a threat” next to the work of another poet, Cheryl Marie Wade, helps to illustrate my point. Wade is an award-winning poet, performance artist, and video maker; she is also the former director of the Wry Crips Disabled Women’s Theatre Project. Although some of Wade’s poetry is available in print form, it is also available in forms that link it to her embodied performance, so that her wheelchair, hand gestures, facial expressions, and tone of voice supplement her written text. In a performance included in Disability Culture Rap, an experimental video Wade codirected with Jerry Smith in 2000, Wade asserts:

I am not one of the physically challenged—

I’m a sock in the eye with a gnarled fist

I’m a French kiss with cleft tongue

I’m orthopedic shoes sewn on the last of your fears

I am not one of the differently abled—

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

I’m Eve I’m Kali

I’m The Mountain That Never Moves

I’ve been forever

I’ll be here forever

I’m the Gimp

I’m the Cripple

I’m the Crazy Lady

I’m the Woman With Juice.12

Although Wade clearly rejects certain identifications (what Simi Linton and others have called “nice words” [14]), the impact of her performance depends on multiplying others: gimp, cripple, crazy lady, woman with juice. Talking back to able-bodied terms and containments, or terms of containment, Wade speaks to “the last of your fears” by implying conversely that crips cannot be contained; even the words most intended to keep disability in its place—such as, of course, the derogatory term cripple itself—can and will return as “a sock in the eye with a gnarled fist.” And the punches keep coming: not only Wade’s own performance but also the location of that performance alongside the many others represented in Wade and Jerry Smith’s Disability Culture Rap suggest that both the number of in-your-face ways that women (and men) with juice will identify and the number of unlikely alliances they will shape is finally indeterminable.

This book is called Crip Theory, but imagining or staging an encounter between Anzaldúa and Wade allows me to position that nomenclature as permanently and desirably contingent: in other queer, crip, and queercrip contexts, squint-eyed, half dead, not dead yet, gimp, freak, crazy, mad, or diseased pariah have served, or might serve, similar generative functions.13 Judith Butler, perhaps, makes a similar point calling one of her essays “Critically Queer.” Positioning her own queer project, through this title, in a permanently indecipherable space (Is she critical of queer, cautioning against its use? Is she insisting that queerness is critically necessary, even indispensable?), Butler writes:

As expansive as the term “queer” is meant to be, it is used in ways that enforce a set of overlapping divisions: in some contexts, the term appeals to a younger generation who want to resist the more institutionalized and reformist politics sometimes signified by “lesbian and gay”; in some contexts, sometimes the same, it has marked a predominantly white movement that has not fully addressed the way in which “queer” plays—or fails to play—within non-white communities; and whereas in some instances it has mobilized a lesbian activism, in others the term represents a false unity of women and men. Indeed, it may be that the critique of the term will initiate a resurgence of both feminist and antiracist mobilization within lesbian and gay politics or open up new possibilities for coalitional alliances that do not presume that these constituencies are radically distinct from one another. (20)

Cautious, in this passage, of how queer “plays—or fails to play,” Butler still leaves open the possibility that it might be deployed in new ways. It is not the term itself that is crucial but whether or not, or how, it might affect or effect certain desirable futures—feminist and antiracist mobilization, coalitional alliances.14 These desirable futures mark queer as a critical term, as crip is a critical term, that in various times and places must be displaced by other terms.

Perhaps, however, to displace Butler herself slightly, we might say, following Wade, that such simultaneous articulation and disarticulation of crip identities and identifications has been part of crip theory from the start: “I’ve been forever I’ll be here forever/I’m the Gimp/I’m the Cripple/I’m the Crazy Lady.” Wade’s language in these lines, regardless of whether it is spoken in performance or written, both affirms and defers her own presence. Conjuring up a range of others not in spite of but through her use of “I am,” Wade perhaps mimics the words of any discounted “crazy lady” living on the streets, perhaps the “out and proud” sentiments of disability pride, perhaps neither, perhaps both. At any rate, from the beginning, and in the beginning, “cripple” or “crip” is not the last word for Wade, even as she paradoxically positions it—and gimp, and crazy lady, and herself—as the alpha and omega.

Finally, however, with its clear rejection of nice words, Wade’s performance is also situated, like Butler’s and Anzaldúa’s, in conversation or contestation with a certain kind of liberalism—for Wade, a nondisabled liberalism that can only imagine, tolerate, and indeed materialize people with disabilities as very special people, physically challenged, differently abled, or handicapable (or, increasingly unable to effect such a patronizing materialization, it can only express frustration—not at the system of compulsory able-bodiedness nondisabled liberalism helped to build and sustains but at people with disabilities themselves, as the supposedly well-meaning lament “I just don’t know what the right term these days is” might suggest). Crip theory extends that conversation/contestation, speaking back to both nondisabled and disabled liberalism and, even more important, to nondisabled and disabled neoliberalism. This book, in fact, is founded on the belief that crip experiences and epistemologies should be central to our efforts to counter neoliberalism and access alternative ways of being.

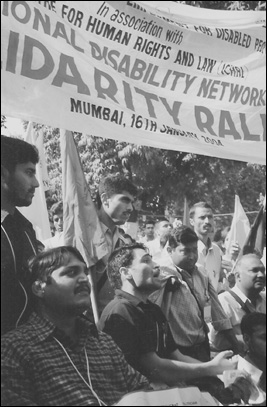

On January 19, 2004, at the Fourth World Social Forum (WSF) in Mumbai, India, a small group of people with disabilities held a press conference. Although the WSF is often understood, and experienced by most participants, as celebrating resistance to the global reach of corporate capitalism, the mood at the press conference was decidedly not celebratory. Some critics have, in the past, charged the WSF with being almost too harmonious, but such a charge could not be leveled at the January 19 event.15 On the contrary, discord—evident in activists’ palpable anger, tension, and disappointment—dominated the press conference as disabled speakers described the ways in which they had been marginalized by the WSF’s organizing committee. The committee, activists contended, had failed to provide access to the forum for people with disabilities and had refused to include a disabled speaker on the WSF’s opening plenary panel. The protest garnered a WSF apology, which was in fact read at the end of the opening session, but activists remained dissatisfied with what they perceived as a merely symbolic or token gesture. Consequently, they came out once again in the evening to hold a candlelight vigil underscoring their critique.

The Mumbai protests demonstrated that disabled people would not be content playing merely a supporting role in what many have called the “Movement of Movements”—that is, the diverse global networks that oppose neoliberalism and imperialism and that collectively compose the most vibrant, fastest-growing forms of progressive activism at the turn of the millennium. In fact, I argue in this section that the protests—and this first example of coming out crip—raise both practical (and local) questions about physical space and theoretical questions about how globalization is currently conceptualized on the left. At the Fourth WSF, these questions were not addressed sufficiently. Disabled activists did make clear, however, that appended apologies would not suffice to redress the ways in which the Movement of Movements was inaccessible; in conversations about alternatives to global capitalism, crips would have to have a seat at the plenary table.

Another world is possible: disability activists in Mumbai, India. Photographs courtesy of Jean Stewart.

From 2001 to 2003, the World Social Forum took place in Porto Alegre, Brazil; the Mumbai conference was the first to be held elsewhere. Initially conceived following a range of important anticapitalist, anticorporate events in the 1990s (including, for instance, the Zapatista uprising against the North American Free Trade Agreement [NAFTA] in 1994 and protests in Seattle that led to the collapse of talks of the World Trade Organization [WTO] in 1999), the WSF was intended at first to shadow the World Economic Forum (WEF), held annually in Davos, Switzerland. At the WEF in Davos, corporate elites, economic ministers from the world’s most powerful countries, and representatives from international financial institutions (IFIs) such as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) met—in private meetings protected by a large cadre of armed guards—to discuss the future of global capitalism. In contrast, at the first anti-WEF, or WSF, in 2001, more than fifteen thousand participants met—in open meetings free from armed guards and apart from IFI or corporate regulation—to generate alternatives to global capitalism and to develop vocabularies and practices of resistance to neoliberalism.

The WSF was not formed to shape global policy but, rather, to ensure democratic spaces where open and forthright discussions of viable and humane futures could take place. The WSF’s organizing committee, following the success of the 2001 meeting, found it “necessary and legitimate” to put together a Charter of Principles to further pursuit of that goal. The first principle of the WSF underscores the importance of access, broadly conceived:

The World Social Forum is an open meeting place for reflective thinking, democratic debate of ideas, formulation of proposals, free exchange of experiences and linking up for effective action, by groups and movements of civil society that are opposed to neoliberalism and to domination of the world by capital and any form of imperialism, and are committed to building a global society of fruitful relationships among human beings and between humans and the Earth. (Fisher and Ponniah 354)

To nurture the kind of openness envisioned by these principles, however, certain exclusions were necessary. In contrast to the WEF exclusions, which were designed to protect the interests of capital and were thus symbolized quite effectively by state-subsidized armed guards, the WSF’s exclusions were designed to protect the interests of voices and communities disenfranchised by the WEF and by neoliberalism more generally. Walden Bello thus explains that “some World Bank officials came and demanded a platform, and were told, ‘No. You can speak elsewhere in the world but this is not your space’” (66). Armed organizations and representatives of political parties were also excluded, although the first three WSFs nonetheless had significant, if unofficial, ties to the Brazilian Worker’s Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores, or PT), which held power at the time in Porto Alegre and the state of Rio Grande do Sul, and which had instituted a range of redistributive economic and social policies in the region. Some have criticized the PT’s central role from 2001 to 2003, suggesting that Brazilian organizers, excluding representatives from political parties elsewhere, had implemented something of a double standard, given their relationship with the PT. Directly or indirectly, the move to Mumbai addressed these concerns and solidified the WSF as an event autonomous from political parties, since Mumbai was (and is) not governed by a progressive political party interested in forging ties with the WSF. The move to Mumbai suggests that, hegemonic discourses of flexibility notwithstanding, the WSF has in many ways, over the course of its history, exhibited a more democratic flexibility as it has moved to respond to various critiques from within the Movement of Movements.

The exclusion of representatives from IFIs, in particular, emphasizes the WSF’s initial role as anti-Davos, whether located in Porto Alegre or Mumbai. The forum evolved away from this role over the years, however. If initially it was largely and directly opposed to the WEF, it increasingly took on an identity in its own right, concerned not just with registering opposition but with generating genuine economic and social alternatives to the policies envisioned by corporate elites in Davos and elsewhere. Hence, from 2002 on, the WSF disseminated the slogan “Another World Is Possible.”

The visionary and unifying idea that another world is possible paradoxically developed at the same time that the forum was being pushed to move beyond harmony and celebration. Emerging from a perceived need to increase the representation and influence of African and Asian participants, Mumbai 2004 both reflected this push beyond celebration and addressed an important critique of the 2001, 2002, and 2003 events. If the exclusion of armed organizations, political parties, and IFIs could be justified, the exclusion of groups (from Africa, Asia, and elsewhere) marginalized by those forces clearly could not. The crip protest can therefore be said to arise directly from the critical ethos founding Mumbai 2004. Related to this, but perhaps even more important, the crip protest can be understood as congruent with the WSF’s first principle (a principle of access), even as it deepens that commitment to access, founding it on an unwavering commitment to literal, local and physical, access.

A more theoretical divide had also been coming to the fore prior to Mumbai and, although the protestors did not speak directly to it, their more integral participation at Mumbai might have done much to further conversation across the divide. As Michael Hardt argues, the Movement of Movements can increasingly be read as addressing divisions between those who

work to reinforce the sovereignty of nation-states as a defensive barrier against the control of foreign and global capital; or [those who] strive towards a non-national alternative to the present form of globalization that is equally global. The first [group] poses neoliberalism as the primary analytical category, viewing the enemy as unrestricted global capitalist activity with weak state controls; the second is more clearly posed against capital itself, whether state-regulated or not. The first might rightly be called an anti-globalization position, in so far as national sovereignties, even if linked by international solidarity, serve to limit and regulate the forces of capitalist globalization. National liberation thus remains for this position the ultimate goal, as it was for the old anticolonial and anti-imperialist struggles. The second, in contrast, opposes any national solutions and seeks instead a democratic globalization. (232–233)

Hardt proposes that the majority of participants in the WSF may well subscribe in some way to the second position, even if, arguably, those most responsible each year for organizing the event subscribe to the first (233).

Hardt’s notion that the forces of democratic globalization are in the majority or ascendancy is promising, but as with other theoretical considerations of globalization, not excluding Hardt and Antonio Negri’s own voluminous Empire and Multitude, it is not always clear how disability figures into the promise. Hardt and Negri repeatedly position the immanent and creative powers of what they term the “multitude” in opposition to the homogenizing, disciplining will to transcendence put forward by “Empire.” The Mumbai protests, however, might complicate this equation. In what ways, if any, can the multitude be comprehended as disabled? How does disability figure into or around the stark yet seductive opposition Hardt and Negri set up, or the stark oppositions put forward by others theorizing alternatives to Empire and corporate globalization? How has disability, in particular, figured into the modern or contemporary nation-state? To what extent, according to the terms of Hardt and Negri’s argument, is the multitude always on the verge of being (necessarily) able-bodied (“what we need is to create a new social body,” they write [ Empire 204]; “we share bodies with two eyes, ten fingers, ten toes … we share dreams of a common future” [Multitude 128])? Must it always, somehow (necessarily, and negatively), guard against association with disability (“the deformed corpse of [the old] society” [ Empire 204])? In other words, as alternative forms of globalization are conceptualized, when and where are able-bodiedness and disability only figures and how might coming out crip, at events like the Mumbai protests, more positively disfigure and rewrite such conceptualizations?

I intend for these to be open questions; a crip reading of Empire is undeniably possible.16 Disabled activists might be well-positioned to negotiate the split Hardt identifies within the Movement of Movements, and perhaps temper the either-or implications contained in his construction of the first (antiglobalization) group’s ultimate (that is, supposedly singular and final) goal of national liberation and the second (counterglobalization) group’s opposition to any national solutions. To access (in all its senses) the other world that is possible, global disability activists may well have committed, at various points, to the state-based limits and regulations advocated by those who, according to Hardt’s schema, directly criticize neoliberalism. Conversely and simultaneously, however, those seeking a democratic (crip) globalization may well recognize that getting many more of their comrades to that democratic space means accessing other solutions that have emerged in transnational or extranational venues.17 If Hardt’s (or Hardt and Negri’s) analysis pinpoints, in short, a divide or even a potential impasse in the Movement of Movements, then crip insights or literacies might help to explode that impasse.18

What is clear from events in Mumbai, however, is that people with disabilities never got the opportunity to play the central part they might have in these debates, at least as they were officially constituted by the WSF in January 2004. Only three hundred of the expected two thousand disabled participants were able to attend the WSF in Mumbai. Hence, beneath banners reading “National Disability Network Solidarity Rally” and “Why Is the World Social Forum Also Marginalising Us?” disabled activists insisted on January 19 that “we do not feel we belong here. We have been struggling since the start of the conference to be recognized but no one seems to care about us and our needs.” Although, for the first time since 2001, a few sessions exploring the ways in which disability and globalization are related did take place (disabled activists had demanded, “if you are coming to India and if you are having the World Social Forum in Bombay, then you can’t have it without disability on the agenda”), it was not easy to secure the panels. Moreover, as Javed Abidi, one of the activists, explained, “they have given us a venue that is extremely shoddy and has a capacity of just 200 people. The venue is near a dump; there are holes in the ground; [they] have made a very shoddy ramp, where my wheelchair cannot go. It is the pits” (S. Kumar).19 The pits, combined with the lack of other basic accommodations (such as no provision for sign language), pushed the group to hold the January 19 press conference and candlelight vigil and to protest outside the opening forum (a panel that included Arundhati Roy and other prominent speakers); “WSF shame, shame,” they shouted.

Along with Abidi, the speakers for one of the official disability panels, “Disability in a Global Perspective: Nothing about Us without Us,” were Anita Ghai, Anne Finger, Jean Parker, and Jean Stewart.20 The other panelists shared the critique put forward by Abidi and the others. Stewart reported that the WSF was exhilarating but stressed that the crip protests were, for her, the highlight. Finger was struck by the organization and leadership of Indian disability activists; clearly, the protests were organized by and for an emerging Third World disability movement. Ghai also spoke at the press conference itself, calling the treatment disabled people had received “embarrassing” and claiming that WSF organizers had initially been reticent about even having official disability panels since they could not perceive how disability might be related to globalization (Mulama). Such a perception will undoubtedly be far less common in the Movement of Movements if (or as) others follow the lead of the group in Mumbai and come out crip.

My second example of coming out crip comes from the directors of the important 1996 film Vital Signs: Crip Culture Talks Back, David Mitchell and Sharon Snyder. In the preface to Narrative Prosthesis: Disability and the Dependencies of Discourse, Mitchell and Snyder explain that their critical negotiation of a range of

institutions and texts brought us to inhabit an increasingly intertwined disability subjectivity. Ironically, the refusal of separate identities along the lines of “patient” and “caregiver” proved to be the monkey’s wrench that brought the gears of many an institution to at least a temporary halt. We jointly plotted strategies of access, interpretation, and survival [and] the experience of disability embedded itself in both of our habits and thoughts to such an extent that we no longer differentiated between who was and who was not disabled in our family. (x–xi)

It sounds rather queer, in some ways, this pleasurable and embodied refusal of a certain kind of compulsory individualism coupled with a rigorous institutional critique, sometimes shutting institutions down and sometimes opening them up. It might be more appropriate at this point to say that queer desires and identifications that resist the commodification and normalization of the past decade (especially the commodification and normalization of gay bodies) sound rather crip.

I do not intend to put forward Mitchell and Snyder’s reinvention of identity politics here for an easy equation of queer and crip experiences; indeed, as I hope my conclusion to this chapter makes clear, crip theory is necessitated at least in part by queer theory’s ongoing inability to imagine such equations. It is no accident, however, that the crip intersubjectivities that Mitchell and Snyder articulate can in some ways be understood as queer. Snyder readily describes how LGBT and HIV/AIDS politics have provided one of the paths to familial and communal identification for her and Mitchell:

I [speak and write] as a child of gay parents who sees queer culture and Castro Street life as a “parent” culture.… It was very early involvement in Project Inform and ACT UP (my dad’s a longterm survivor) that eventually led David and me to work in disability studies as well as serious mentoring by queer theorists … that resulted in [the anthology we edited] The Body and Physical Difference: Discourses of Disability. [We] have often joked that the only film festival that would truly have “gotten” Vital Signs: Crip Culture Talks Back would be the SF gay/lesbian fest. Our other joke title for the video is “Disabled women, gay men, and Harlan talk back.”21

Moreover, Jennie Livingston’s Paris Is Burning—the acclaimed 1992 documentary about African American and Latino/a drag balls in New York City—was one of the direct antecedents for Vital Signs. One of the queerest aspects of Vital Signs, however, may be its refusal to reproduce any “parent culture,” even a queer one, faithfully. If Paris Is Burning allowed for “narration of subcultural attitudes and practices” (Mitchell and Snyder, “Talking about Talking Back” 210), it also at times made use of an exoticizing anthropological gaze that Vital Signs, from its “talking back” subtitle on, more actively and successfully resists.22

Vital Signs was filmed during the opening up—to disability experiences and perspectives—of one institution in particular, the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, which held a conference titled “This/Ability: An Interdisciplinary Conference on Disability and the Arts” in 1995. The conference was organized by Susan Crutchfield, Marcy Epstein, and Joanne Leonard, and—at the time—was only the second such conference dedicated specifically to disability studies in the humanities (the first was “Discourses of Disability in the Humanities,” held at the University of Puerto Rico, Mayaguez, in 1992). The numerous speakers and performers in Vital Signs—including Sandahl, Finger, Robert DeFelice, Kenny Fries, and others—were all participants in “This/Ability.” Crutchfield, Epstein, and Leonard agreed to the filming of some parts of the event; Vital Signs is the documentary resulting from the multiple interviews and performances Mitchell and Snyder collected. As individuals in Vital Signs“talk back” to the camera, a politicized and increasingly intertwined crip subjectivity—not unlike the subjectivity Mitchell and Snyder describe as animating their own family life—materializes. Vital Signs, in fact, extends to and learns from an ever-expanding range of others the crip subjectivity that Mitchell and Snyder discuss elsewhere.

Initially, Mitchell and Snyder intended Vital Signs to document the emergence and evolution of disability studies in the academy; their plan for observing the University of Michigan event was not unlike de Lauretis’s observation of what was taking place academically, in a queer context, at the 1990 Santa Cruz conference. What resulted, however, makes de Lauretis’s earlier, more straightforward academic observation, appear rather staid; Mitchell and Snyder realized that they had “the rough outline of a film about disability culture” (“Talking about Talking Back” 198). Or, as the subtitle of their documentary suggests, a film about crip culture. The evolution of Mitchell and Snyder’s film underscores, as I suggested at the beginning of this chapter, that crip theory has emerged far more readily in activist and artistic venues. It also underscores not that crip theory has no place in the academy—the filming of Vital Signs did occur at the University of Michigan, after all, and many participants had academic affiliations—but that it—and the practices of coming out crip it makes possible—nonetheless will or should exist in productive tension with the more properly academic project of disability studies.

Mitchell and Snyder locate Vital Signs within a “movement of film and video in the mid-1990’s that would seek to narrate the experience of disability from within the disability community itself.… What these visual productions all shared was a commitment to telling stories that avoided turning disability into a metaphor for social collapse, individual overcoming, or innocent suffering” (“Talking about Talking Back” 208–209). Toward that end, included in the video are interviews with activists such as Carol Gill and poetic and literary performances by writers such as Eli Clare (talking about cerebral palsy and “learning the muscle of [the] tongue”) and Finger (reading her story of a fictionalized love affair between Helen Keller and Frida Kahlo). Solo autobiographical performance pieces in Vital Signs include those by Sandahl, who performed in a lab jacket with medical terminology written on it, drawing attention to the ways in which people with disabilities are treated as though diagnoses were literally written on their bodies and thus constantly available for scrutiny; and Mary Duffy, who confronted audiences as a nude Venus de Milo, thereby challenging, through her crip invocation of the highest echelons of Western art and culture, the reduction of her body to “congenital malformation.”

For all of the performances and interviews documented in Vital Signs, Mitchell and Snyder were committed to filming disabled people speaking in their own voices. They filmed each speaker from a low angle, since they wanted their subjects “to tower over the viewer with their images punctuating their political positions and artistic caveats” (“Talking about Talking Back” 201). Looking back on this filmic choice, Mitchell and Snyder note Wade’s performance: “When Cheryl Marie Wade … exclaims, ‘Mine are the hands of your bad dreams—booga, booga—from behind the black curtain,’ we wanted our audience to viscerally feel the challenge as she displays her ‘claw hands’ on screen” (201). The compilation that results from these images, however, ironically suggests again that coming out crip has very little to do with individuality as it is traditionally conceived. If a commitment to filming disabled people speaking in their own voices puts forward a fairly recognizable (and still important) version of identity politics, the resulting film participates in a reinvention of identity politics. Along with the individuality claimed or spoken by all of those in Vital Signs, Wade’s “Mine” in this piece, like the “I am” I analyzed earlier, gains its meaning primarily from the larger and emergent communal (crip) context represented in the film.

Vital signs, in a strictly medicalized context, refer to that which is supposedly most undeniable about the human condition at any given moment: Are the blood pressure and temperature normal? Is the system compromised in any way by infectious agents? Is the patient’s chart upto-date? The film’s supplemental understanding of “vital signs,” however, like the cultural signs of disability and queerness I am tracing throughout this book, refuses the fixation on life as understood in strictly medical terms. And indeed, as the proliferation of crip identifications in the film makes clear, the system has been compromised by infectious agents—or, put differently, by a communicable disability agency. Even when, as in Sandahl’s performance, the seemingly incontrovertible medical sign is invoked, its (singular, originary) life or presence is not guaranteed. Crip vital signs work otherwise and can never be fully or finally fixed.23

Even as Mitchell and Snyder later write about the making of Vital Signs, in an essay titled “Talking about Talking Back,” a nonindividual crip subjectivity comes to the fore: stills from Vital Signs do not, in the essay, always directly gloss or exemplify what the filmmakers are arguing. Instead, these stills are included with captions excerpting part of each speaker’s story, as though the speakers are providing a running (and supportive) commentary on the essay. Harlan Hahn, for instance, is depicted with the caption “Once we begin to realize that disability is in the environment then in order for us to have equal rights, we don’t have to change but the environment has to change” (204). The authors do not comment directly on this observation that instead speaks—but certainly, given the repetition of such a point in many crip contexts, without Hahn as its definitive source—alongside them. If, in other contexts, coming out crip for Mitchell and Snyder made it difficult for able-bodied subjectivities, institutions, and authority to function efficiently, in the context of the film and the cultural efflorescence it represents, coming out crip—inefficiently, contagiously—allows for the emergence of new disabled subjectivities. A reinvented and collective identity politics flourishes in and around Vital Signs; the birth of the crip comes at the expense of the death of the (individualized, able-bodied) author.

Carrie Sandahl in Vital Signs: Crip Culture Talks Back.

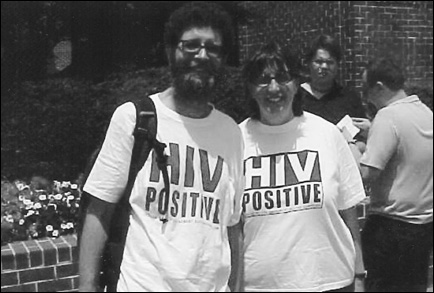

I’m going to use myself to introduce my third example of coming out crip. In January 2004, at a meeting focused on “Interiorities” in Maastricht, Netherlands, I came out as HIV-positive. I’m not, as far as I know, HIV-positive, though like many other gay men of my generation (coming of age sexually at the very beginning of the AIDS crisis), I’ve had lovers who are positive and, actually, I’ve spent not insignificant periods of my adult life unsure of my serostatus. Nonetheless, although literal disability accommodations did get me on the plane to Amsterdam, those accommodations were not related to HIV. I came out as HIV-positive for two reasons. First, the interdisciplinary expert meeting where I was speaking was meant to explore “the experience of the inside of the body,” and as the sole representative of queer theory and disability studies, I wanted to draw attention to the politics of looking into queer and disabled bodies (I wanted to raise questions, in other words, about what exactly people wanted or expected to see inside disabled and queer bodies). Second, the paper was on South Africa’s Treatment Action Campaign, or TAC.

Perhaps five million people or more are living with HIV or AIDS in South Africa (approximately one in nine people). In 1998, after an AIDS activist was murdered by neighbors who were angry that she disclosed her HIV-positive identity, TAC began producing t-shirts like the one I wore at the Maastricht meeting: the front side of the t-shirt simply says “HIV POSITIVE” in block letters; the back can vary, but the version I wore declared “STAND UP FOR OUR LIVES” and “Treat the People,” next to a photograph of Nelson Mandela in a TAC shirt.24 The version I wore announced a February 2003 march for HIV/AIDS treatment, but by 2003–2004, the shirts were worn in many different contexts. The shirts are now worn, in fact, by almost everyone involved with TAC, whether in Africa, Europe, or the United States. At rallies and events, HIV POSITIVE t-shirts can be seen everywhere you look—this was the case, for instance, according to Joe Wright, who was working with TAC in South Africa at the time, at the TAC National Congress in summer 2003, which brought together delegates from around the country. Activists also often wear the shirts in more individual contexts; an HIV-negative friend of mine tells me she was approached on a South African beach by someone who came up to say “you’re very brave to disclose your HIV status like that.” As my friend’s anecdote suggests, and as Wright reports, “the T-shirt practically shouts, ‘I have HIV.’ And so that’s the first question many people ask whoever is wearing the shirt: ‘Do you have HIV?’” Wright explains that activists generally resist or evade this question, thereby implicitly (or explicitly) insisting, “It’s not your HIV status that matters most, but your HIV politics” (“Commentary”).

TAC’s project is not always explicitly queer, though Zackie Achmat, who founded the group, had a history of both anti-apartheid and LGBT/queer activism (his activism, in fact, helped establish the National Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality in 1994). Achmat, who is living with HIV, began a unique kind of “hunger strike” in 1999, refusing to take expensive antiretrovirals until they became more widely available for the many other South Africans with HIV/AIDS. In August 2003, Achmat ended his hunger strike; he now adopts what he calls a “fifty-year perspective” that will “ensure access for all and the development of a public health system.” Achmat’s understanding of access has consistently been both local and global, and he therefore positions himself and TAC as “part of a global movement that sees health as a human right” (Musbach).

Despite the fact that TAC’s project is not always explicitly queer, Achmat’s history as a gay activist certainly energized the group and there are numerous ways in which TAC’s t-shirt campaign, in particular, dovetails with earlier queer projects that likewise contingently universalized HIV-positive identity. In England, the Terrence Higgins Trust at one point, for instance, deployed the campaign “Safer sex—keep it up! Positive or negative, it’s the same for all” (King 214). The point of the campaign was intragroup solidarity in the interests of communal and cultural survival: in contrast to heterosexuals committed to the illusory goal of “finding a safe partner,” gay men at the time committed to safe practices. As Cindy Patton suggests, rather than never talking about sex in public and then endlessly interrogating one’s partner in private (the U.S. heterosexual model), gay men in North America and Europe committed to an “emancipatory model” continually talked and debated safer sex in public and thus did not need to grill our partners, however multiple, in private (indeed, when the private grilling didn’t happen it on some level marked one’s political commitment to communal solidarity) (Fatal Advice 108–111; Inventing AIDS 46–49). These commitments (to safer practices and to textured, public conversations about sex) validated that the variety of life-affirming cultural forms and relations we had generated outside compulsory heterosexuality, and outside the couple form, would remain viable. One (and only one) of the lines of descent for TAC’s t-shirt campaign might be understood as these queer projects of solidarity and contingent universalization of HIV-positive identity—projects of solidarity now largely lost as far as North American and European AIDS activism is concerned.25

Activists in TAC t-shirts outside Bush reelection headquarters in Arlington, Virginia. Global Day of Action on HIV/AIDS, June 24, 2004. Photograph courtesy of Sammie Moshenberg.

Achmat founded TAC on International Human Rights Day, December 9, 1998. The group has three main objectives: “Ensure access to affordable and quality treatment for people with HIV/AIDS; Prevent and eliminate new HIV infections; Improve the affordability and quality of health-care access for all” (TAC: Treatment Action Campaign, “About TAC”). A major victory was scored on December 9, 2003 (the fifth anniversary of TAC’s founding) when an agreement was reached allowing for generic antiretrovirals to be made available in the forty-seven countries of sub-Saharan Africa. This victory was largely attributable to the pressure TAC consistently applied, both to the South African government and to multinational pharmaceuticals such as Boehringer Ingelheim (BI) and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). The agreement determined that (1) producers of generic antiretrovirals would be given licenses to disseminate their compounds across sub-Saharan Africa, subject to royalties, not to exceed 5 percent, to be paid to the pharmaceuticals holding name-brand patents (according to the agreement, the licenses would be “voluntary,” which simply meant that BI and GSK would not be faced with governments bypassing their authority and mandating that licenses be granted to those producing generic medicine); (2) producers of generic antiretrovirals would be allowed to market and distribute their versions across sub-Saharan Africa, which would make treatment available at roughly US$140 per patient per year; and (3) producers of generic antiretrovirals would be allowed to generate new combinations from the various compounds available, which “reduces the risk of resistant virus strains appearing and is therefore an important innovation in treatment” (Rivière). Nathan Geffen of TAC insisted that this agreement was “a further sign that a new internationalism is emerging to fight the parallel globalizations of the epidemic and of intellectual propety rights,” while Ellen ‘t Hoen of Doctors without Borders cautioned that “we need to make sure that GSK and BI do not apply delaying tactics—but the eyes of the world are once again turned on them, and they know that the legal case can be reactivated if they don’t comply” (Rivière).26

In Maastricht, in the context of the January 2004 expert meeting on interiority, I found ‘t Hoen’s insistence on exteriority, on keeping the eyes of the world focused on the ever-shifting machinations of multinational pharmaceuticals, multinational corporations, and neoliberalism, crucial. I called my own paper “On Me, Not in Me” both to invoke another safe sex slogan from the early days of AIDS activism and to raise questions about ways of seeing, questions about when and where looking inside the body works in tandem with the relations of looking shaped by global movements for social and economic justice and when and where looking inside the body works against those relations. Although TAC’s t-shirt promises a glimpse inside, it also defers that glimpse. Ultimately, TAC t-shirts will not satisfy a desire to locate a picture (or an identity) definitively (safely?) within an individual—even as they nonetheless on some level generate that desire (and in staging a Brechtian dissonance it forces viewers of the shirt to think differently).

In my presentation, I withheld the metareflection on my own t-shirt that I am offering in the context of this chapter—a metareflection that now entails, for me personally, coming out as HIV-negative. I knew that I had been in sexual situations where HIV was unquestionably on one side of the condom, a thin layer of latex (spatially, that is, the tiniest barrier) and potentially a split second in time (temporally, again, the tiniest barrier) separating one interior space from the other. But given the ways in which my paper was functioning in that very specific rhetorical context (apparently straight and nondisabled), I declined to say which side of the latex the virus was on. In the very different context of this chapter, I find it more important to raise issues about what it means, for the purposes of solidarity, to come out as something you are—at least in some ways—not.27 To build on the previous section, coming out crip at times involves embracing and at times disidentifying with the most familiar kinds of identity politics. In another context, away from my computer screen and apart from the imagined audience for this chapter, I will undoubtedly put on a TAC HIV POSITIVE t-shirt again. And I continue to recognize (and re-cognize) the disability insight that was not necessarily named as such when it was voiced in the 1980s: if the AIDS crisis is not over, HIV-negative status is never guaranteed. TAC’s work is dedicated to emphasizing that, indeed, the AIDS crisis is not over (another slogan that formerly animated North American and European activism) and to mobilizing identifications against the global structures that sustain the epidemic by capitalizing on those most affected by it.

Finally, I will put forward what might be read—at least initially—as a counterexample of coming out crip, even if it is quite recognizable as a textual disability studies analysis. In February 2004, Fox Television premiered a brief (two-episode) dating reality show called The Littlest Groom. Like other dating shows, The Littlest Groom, set in an enormous and luxurious Malibu mansion, focused on one person’s consideration and elimination of a dozen or so others, so that in the end only one final date remained. Also like most (but not all) such shows, the one doing the choosing and the ones chosen were of the opposite sex; in this case, Glen Foster was put forward as the bachelor choosing from a selection of single women. Monetary prizes are usually awarded in the final episode, and although the prizes in The Littlest Groom were not as valuable as the prizes on other dating reality shows, the female winner, Mika Winkler, did receive a two-carat diamond ring, and Fox Television sent Foster and Winkler on a Mediterranean cruise.28

By 2004, viewers of dating reality shows had come to expect both these standard (even naturalized) components of the genre, as well as something supposedly unexpected—a catch or twist (or both) that seemed to set the show apart from the numerous dating reality shows that had preceded it. In this case, the catch, as the title suggests, was that The Littlest Groom was a short-statured man selecting his date from a group of beautiful and articulate short-statured women. Or, at least, that’s what the participants assumed was taking place. Halfway through the show, Fox introduced the twist—Glen had narrowed his choices to five women when Dani Behr, the host, informed him that three new, average-statured women would be thrown into the mix. “This should be interesting,” one of the average-statured women said as she kissed Glen hello and joined the group of contestants.

Disability studies and the disability rights movement make it extremely easy to critique The Littlest Groom: it can be read as functioning as a latter-day freak show, and Fox’s marketing of it alongside another show centered on bodily (and behavioral) difference (My Big, Fat, Obnoxious Fiancé) only underscores such a reading—it was as though both shows were part of the extraordinary wonders audiences could discover were they to “step right up” to the circus that is Fox Television. In fact, this reading is so readily available that both mainstream discussions of the series and left-oriented critiques, almost universally, took note of The Littlest Groom’s freak show aspects. A commercial website dedicated to the simulacrum “television news” invoked P. T. Barnum directly, accurately explaining that “P. T. Barnum made Charles S. Stratton, better known as General Tom Thumb, a celebrity in the mid-1800s and orchestrated Stratton’s marriage to Lavinia Warren into a huge event breathlessly covered by the day’s press.” Linking Barnum’s efforts to capitalize on Stratton and Warren to Fox’s efforts to capitalize on The Littlest Groom, the article reinvoked Barnum’s famous slogan, “there’s a sucker born every minute” (“FOX Thinks Small”). From another location on the political spectrum, queer theorist Judith Halberstam, writing for the Nation, insisted that “the midget show bombed because it exposed the ‘freak show’ aspect of all marriage shows” (“Pimp My Bride” 45). Although neither the articles boosting or advertising the show nor, as with Halberstam’s, panning or critiquing it, put forward a critically disabled reading (as Halberstam’s unfortunate description of The Littlest Groom as “the midget show” and use of it as only a metaphor for other dating reality shows attest), the fact that it was so readily perceived as a freak show, from so many different political and cultural vantage points, lays the groundwork for a disability studies analysis.29

First, for the producers and for many viewers, the show was only about height or physical difference, and the streamlining of the program to two episodes suggested either that the network didn’t believe viewers would care about getting to know these participants for more than two episodes or that the network consciously or unconsciously perceived the short-statured women as basically indistinguishable from each other (so that, again, more than two episodes would simply not be necessary). Second, a standard defense of many dating shows, including The Littlest Groom—that love looks beyond the exterior; that what is important is personality or what’s on the inside—was belied by the fact that no other dating show had included a short-statured contestant. On The Littlest Groom, average-statured women may have been introduced to drive home the ideological point that what counts is not height or physical difference but the person, but for this thesis to be even partially convincing, short-statured contestants (or Deaf contestants, or contestants using wheelchairs or crutches) would have to be equal participants on The Bachelor, The Bachelorette, Joe Millionaire, Boy Meets Boy, and other popular dating shows. Finally, and most important, The Littlest Groom did almost nothing to displace dominant and gendered conceptions of beauty: all the contestants were, apparently, white and in many ways representative of hegemonic Euro-American standards of beauty. On this last point, in particular, disability studies is particularly apropos for reading not just The Littlest Groom but the entire corpus of reality television, from dating to “extreme make-over” shows.

And yet, if all of this positions The Littlest Groom as a counterexample of coming out crip, a certain disability identity politics of course also makes it possible to read the show against the grain, and I intend for my subheading—“Crip Reality”—to convey that possibility: “crip reality” need not be a substantive entity, as if anything in the genre had much to do with “reality,” as it is conventionally understood, anyway. It can, rather, trace a cultural process, focusing on the myriad ways in which disabled and allied audiences in a sense “crip” culture in order to imagine and forge spaces for themselves within it. The brevity and the structure of the show might work to construct the contestants on The Littlest Groom as indistinguishable, but they themselves consistently foreground difference. The short-statured women in The Littlest Groom, including Mika, discuss age differences, education differences, and family differences (raising the issue, for instance, of growing up in a short-statured family versus growing up apart from a short-statured community). As several disability studies scholars have argued, beneath, through, or around the freak show, disability resistance is discernible. And surely—partly thanks to the short-statured women themselves—some viewers discerned such resistance; for some audience members, the pleasures of The Littlest Groom were undoubtedly disability pleasures, whether those pleasures emerged from the simple fact that short-statured men and women were being represented in the media as intelligent and desirable (however much that representation reinforced other problematic norms) or from subtler aspects of the show, such as the anger legible on the short-statured women’s faces when the twist was introduced—anger that spoke volumes about just how aware these women were about the enfreakment process short-statured women an men are subject to on or off television.

Still, this reading can in turn be cripped, which is my main intention in this section and the next. American Sign Language represents what translates as “visual clutter” with both hands extended as though they were tiger claws—moving these up and down with a repulsed grimace on the face conveys the “noise” generated by images clashing in a visual field. And for me, the visual clutter begins with that Malibu mansion. I’m convinced enough by what Mike Davis calls “the case for letting Malibu burn” to question just how desirable disability integration into that particular corner of the society of the spectacle might be. I recognize that The Littlest Groom was a dating show, not (to pick another possibility from reality television) a survival show, representing its contestants withstanding the forces of nature. But locating dating shows in opulent sites of Western consumption (as though such sites were not also subject to the forces of nature) and survival shows in a non-Western “wilderness” or “wild” locations (like the Australian outback) within the West (as though such sites did not include nearby Hilton or Sheraton hotels capable of supporting television crews) is another mere convention of the genre. Viewers of The Littlest Groom may not have seen Malibu burn, but such a scenario is not unimaginable in this location; it is only unimaginable according to the terms of the genre.

Breaking with those terms, I want to use the scenario of Malibu burning to begin to make a different kind of sense—spatial, regional, crip sense—of the images captured by Fox Television and, in a way, by disability studies. At times, disability studies—like other fields centered on minority experiences—has put forward narrowly textual readings focused on the representation of disability and on texts consumed apart from an identifiable site of production. Crip theory resists such dislocations or, rather, insists that accessing (or making accessible) the “circuit of culture” entails attending to the sites where images and identities are produced (du Gay et al. 3–4). Locating crip identities in this way, far from displacing attention to images of disability, has the potential to generate new and perhaps unexpected images—of disability solidarity and coalition.30

In Ecology of Fear, his study of the politics of so-called natural disasters in Los Angeles, Davis examines the deadly fires that have plagued Malibu for most of the past century. Despite the fact that the Malibu area has an incredibly high propensity to wild brush fires, the location is home to some of the highest-priced real estate in the country. Wealthy homeowners and developers, rather than evacuating the area, have managed to wield their political clout to secure some of the costliest federal disaster assistance and protection available—safeguards against the destruction wrought by the fires that regularly ravage the area, destroying thousands of homes and claiming dozens of lives. Malibu residents, along with others on southern California’s “fire coast” have adopted a policy of “total fire suppression” (99, 102)—that is, a policy that seeks to eliminate the possibility of ignition. This policy has had deadly effects: (1) it ignores the fact that “fuel, not ignitions” (101) feeds California’s wildfires—and in the concrete and car culture of southern California there is plenty of fuel; (2) it disrupts the natural rhythm of relatively contained brush fires, which are now essentially outlawed (Mexico’s Baja California, in contrast, has neither the policy of total fire suppression nor the history of cataclysmic fires); (3) avoiding political and economic causes for Malibu’s fires, it uniformly demonizes those individuals who ignite fires, often homeless people attempting to keep warm; and (4) it ultimately leads to massive cuts in services for the state’s poorest residents (who are, for what it’s worth, disproportionately disabled)—because Malibu’s fires are “natural” disasters rather than disasters of real estate speculation and development, residents are eligible for massive relief funds (basically, state-subsidized insurance) designed to protect the investments capial has made in the area. Whether we can still call The Littlest Groom “reality television,” given that so many spatial realities are effaced by the program, is seriously open to question.

Marta Russell’s “Manifesto of an Uppity Crip” (in Beyond Ramps) similarly crips the spatiality of southern California. Although she is consistently attentive in her work to the ways in which images of disability are deployed to secure or counter able-bodied ideologies of pity, freakery, or revulsion, Russell insists that both dominant and marginalized identities emerge in specific locations and in relation to others and that neoliberalism has made those locations and relations increasingly insecure. In an essay ranging widely over political economy, disability identity politics, and what she and others call “the end of the social contract,” Russell notes:

Several years ago a fire erupted in a canyon in Alta Dena, California [near Malibu, and Malibu did burn during the Altadena fire]. Homes were destroyed, quite unintentionally, by a homeless man who lit a fire to keep warm on a cold night. The fire caught some bushes and spread into the hills, burning everything in its path for miles. The homeowners’ loss was a social issue for the entire city, for if this man had had shelter and warmth there would have been no brush fire to burn out of control. The unheeded lesson of the Alta Dena fire was that we are all linked and until everyone is safe, no one is safe; until everyone has a home, no one’s home is safe. (215–216)

If a certain disability identity politics allows for limited pleasure in the short-statured integration of both Malibu and compulsory heterosexuality, another kind of coalitional and postidentity, politics allows Russell to imagine southern California spaces differently, and to foreground the ways in which images of both disability and political economy should be a central concern to radical uppity crips.

Yet what might an uppity crip politics look like, and how might it function, in this space that (in Malibu and throughout the region) encompasses countless homeless people, as well as the luxuriously housed; that generates more images for global consumption than any space on earth, even if links between those images are obscured or discouraged and even if some images seem perpetually unavailable for re-presentation (in this place that purports to make anything available for representation); that seems to traffic equally in a hypostatization of fantasy (the dream factories of southern California generating what we all should really desire) and reality (the studios generating, and dubbing “reality,” both productions like The Littlest Groom and action news footage of Malibu brush fires); that symbolizes and markets a peculiarly Californian version of “freedom” despite being a virtual and literal fortress, home to one of the largest concentrations in the world of military-industrial institutions; that allows for (and, perhaps, to return to the language of the introduction, tolerates) Los Angeles–based writer Russell identifying defiantly as an uppity crip even as thousands of others just across town, primarily African American young men, likewise identify as “Crip,” with an understanding of identity that would seem to have no connection to what Russell and disability activists are getting at with their use of the term? Is it even possible for “crip reality” to figure coherently here (even temporarily or contingently), either as a substance or a process?

Although the previous section turned from disability work on the image to cultural geography (the field concerned with how meanings, histories, and political economies emerge spatially), an optimistic ambivalence in other directions is equally imaginable.31 Permanently partial, contradictory, and oriented toward affinity (Haraway 154–155), crip reality keeps on turning.32 Or, to adapt the words of Michael Zinzun, who was shot and blinded when he tried to stop a police beating in his L.A. community (Smith xx), crip theory puts bodies and ideas in motion:

I ain’t got no big Cadillac,

I ain’t got no gold …

I ain’t got no

expensive shoes or clothes.

What we do have

is an opportunity to keep struggling

and to do research and to organize. (Qtd. in Smith 20)

The Malibu fires, for Mike Davis, are understood as necessarily connected to other events and specific communities: Davis not only challenges dominant representations of homeless people as the “incendiary Other” (Ecology of Fear 130); he also suggests that the construction of California wildfires as natural disasters for communities like Malibu makes it difficult to analyze (or make newsworthy) cultural disasters like tenement fires in the city of Los Angeles or political struggles like those of the largely immigrant communities who occupy such buildings. In November 1993, a month when Malibu fires were widely publicized on both a local and national scale, three occupants of a residential hotel in downtown Los Angeles died and twelve others were severely burned. The death toll in Malibu was also three, but as Davis argues, because the “property damage differed by several orders of magnitude.… [A] double standard of fire disaster was rubbed in the faces of the poor—in this case, Mexican and Guatemalan garment workers” (130). The immigrant workers in the building had long attempted, in struggles with the building’s owners, to draw attention to landlords’ (or slumlords’) “notorious record of fire, health, and safety code violations” (130). Apparently neither resources nor dominant media representations could be mobilized to draw attention to these disasters. Davis, however, deconstructs the opposition between the natural fires in Malibu and the cultural fires downtown and thereby spotlights the struggles of immigrant communities in Los Angeles. Or, put differently, Davis calls back the disappeared—that is, communities whose struggles must be dematerialized in order for other Los Angeles experiences to be represented and broadcast as “reality.”

The specific struggles of disabled communities, though, are another story altogether. Just as spatial analysis has largely been absent from the work done in disability studies on images (like the images of short-statured women and men in The Littlest Groom), disability has been largely incidental to the work of cultural geographers. In a consideration of the 1992 Los Angeles riots, for instance, Davis draws attention to the crackdown on undocumented immigrants and notes, tellingly, that “even a 14-year-old mentally retarded girl … was deported to Mexico” (“Uprising and Repression” 145). If Davis’s work makes available for analysis the specific struggles of minority or immigrant groups, the same cannot be said about his rhetorical use of people with disabilities. In this passing example, the disabled girl herself basically only functions as what Mitchell and Snyder would call a “narrative prosthesis” for the larger story or political economy that Davis wants to put forward.33 For cultural geography more generally, such uses of disability are not uncommon—disability amplifies theses about the excesses of capitalism or nativism or imperialism, but (and consequently) cannot function on another register, more actively or desirably engaged in the struggles geographers recount.34

I open this section with Zinzun, however, both to transition toward the crip reality that has more often concerned Davis and other Los Angeles writers and to suggest that disability is not, in fact, incidental to that reality. To focus in this section on the Los Angeles–based Crip street gang (actually dozens of different gangs now in existence in many locations across the country) might initially appear to dwell on a mere linguistic accident, the coincidence of the name “Crip.” According to LaMar Murphy, however, gang life leads to one of three outcomes: “You’re gonna be dead, locked up for the rest of your life, or paralyzed in a wheelchair.” Murphy is one of four African American, disabled men interviewed in Patrick Devlieger and Miriam Hertz’s The Disabling Bullet, a Chicago documentary film about life after gang-related gunshot injuries. Gang studies, in general, has focused more often on death and prison; this section thus calls back the (disabled) disappeared. Although I move toward a consideration of literal disability here, toward life after the bullet, I want to stress that disability has nonetheless haunted Crip reality from the beginning, in generative ways that exceed how disability has been imagined and metaphorized by cultural geography.

The origin of the Crips is at this point the stuff of mythology. One origin story has it that the name of the gang was initially an acronym, standing for “Continuing Revolution in Progress” (Hayden 167) or—alternatively—“Continuous Revolution in Progress” (Davis, City of Quartz 299). Whether the acronym was in circulation in the early 1970s or whether it was a later invention that retrospectively gave meaning to the gang name, it in some ways contradicts other stories about the group’s origin, which would position late-1960s and early 1970s gang activity not as a function either of a thriving or continuous civil rights movement or Black Panther revolution but rather as a function of revolution’s demise: “the failure of radicalism,” in Tom Hayden’s assessment, “bred nihilism” (167).