When the New Masses was founded in 1926, there was virtually no Trachtenberg-type “Party supervision”–and scarcely any curiosity exhibited–by the national or international Communist leadership. This loose state of affairs persisted through the first years of the Depression when Walt Carmon (1894–1968) moved to New York City from Chicago. In Chicago, Carmon had once worked for the Labor Defender (the publication of the Party-led International Labor Defense) and also assisted as circulation manager of the Daily Worker. In New York, he served as managing editor of the New Masses from 1929 to 1932.1 By the time he arrived, the $27,000 originally donated by the radical Garland Fund to launch the publication had been depleted, and Carmon was frantic to locate new funding sources. Within a short time he devised a program of fund-raising masquerade balls during the fall and spring at Webster Hall in Manhattan.

Carmon was a Party member but didn’t pay dues or attend Party meetings; his wife Rose recalled that he was a disciplined Communist only when it served his purposes. Carmon saw the New Masses as a literary-art magazine with a Left slant rather than as a political organ. In his view, politics was the province of the Daily Worker, which was why staff salaries there were far more regular than at the New Masses, where contributors received no payments and staff members were lucky if they got $5 a week. Carmon was an anomalous Communist literary functionary for New York City; he was not Jewish (although he loved Yiddish expressions), nor even an Easterner. Midwestern novelist Jack Conroy and other writers from outside New York felt particularly comfortable in dealing with him.2 Moreover, Carmon was priceless in directing non–New York writers toward publishers potentially interested in their work.

The free-wheeling atmosphere of the New Masses office was reflected, perhaps in extravagant fashion, in the recollections of the radical poet Norman MacLeod (1906–1985), who worked with Carmon and became his friend.3 MacLeod’s father was an alcoholic businessman from Scotland who met and married MacLeod’s mother in Utah, then divorced her and disappeared. His mother took graduate studies in London and taught at universities in Montana, Iowa, and southern California, finally becoming head of the speech department of Mount Holyoke College in the 1930s. MacLeod attended high school in Montana and Iowa but was disoriented and unhappy due to the uprootedness of his youth, the ups and downs of his family’s financial situation, and unpleasant memories of both his father and his mother’s second husband. He held a number of jobs and hoboed extensively before attending the University of Iowa for three years and finishing at the University of New Mexico, where he received a B.A. in 1930. His interests included literature and anthropology, and he pursued graduate work at other schools for several more years on and off during the Depression. MacLeod episodically edited poetry magazines and held teaching jobs, but drinking and marital problems pursued him like furies to the end of his life.

MacLeod started writing poetry at the age of thirteen, and his work appeared in the 1920s in several little magazines, including Jackass and Troubador; later on he personally edited certain others, such as Morada and Front.4 His first two books of poetry, Horizons of Death (1934) and Thanksgiving before November (1936), are noteworthy for their blend of imagism and regionalism. He subsequently wrote a novel about the Federal Writers’ Project, You Get What You Ask For (1939), and a semi-autobiographical work covering the years 1917–20, The Bitter Roots (1941). MacLeod envisioned himself as a revolutionary after 1928, and in January 1931 joined the staff of the New Masses on which he served for eight months, solely editing the March 1931 issue that featured Whittaker Chambers’s widely discussed story, “You Can Make Out Their Voices.”5 In late 1931 MacLeod was in southern California, where he briefly held membership in the Party and helped to set up the Hollywood chapter of the John Reed Club. After that he sojourned in Europe, the Soviet Union, and sundry parts of the United States. Although he was distressed by the Moscow Trials, he was determined to keep antifascist work his top priority; this enabled him to uphold the stance of an independent Communist until the 1939 Hitler-Stalin Pact.

MacLeod’s recollection of the semi-bohemian ambience of the New Masses in the early 1930s suggests one of the reasons why Carmon’s managing editorship came under fire. He recalled that Carmon kept a drawer full of poems and selected ones for publication based on the number of lines he had available.6 This drawer was adjacent to another one that housed the scented love letters that poured in for Mike Gold. Gold only came to the office at odd intervals, but he did appear shortly after the novelist Charles Yale Harrison (1898–1954), a pro-Communist writer who authored the successful Generals Die in Bed (1930), had fallen into disfavor for alleged Trotskyist sympathies. Gold noticed a copy of Harrison’s novel on the desk, took one look at the inscription (“For MG, Yours for the Revolution, Charley”), grunted, and tossed it out the office window.7

MacLeod later insisted that “I knew Mike and Wally were members of the CP-USA, but while I was on the New Masses nobody ever suggested that I join the Party and I didn’t.” He recalled three decades after his disaffection from the Party that he “never saw any indication that [Wally] was not his own man, no evidence that he was controlled and dictated to by the CP-USA.”8 MacLeod claimed as well that the formation of the John Reed Clubs was not initiated by the Party leadership; it had been organized after Carmon kicked a bunch of young writers out of the New Masses office. They had been hanging around too much, and to get them out of his hair he told them to “go out and form a club.”9 Rose Carmon confirmed the story and recalled that Carmon added, “I’ve even got a name for you–call it the John Reed Club.”10

The advent of the John Reed Clubs, nonetheless, created a new complication, because among the hundreds of young radicals drawn to it were many Young Turks with ultrarevolutionary opinions.This was especially conspicuous among members of the New York Club, the most consequential one, who soon began aiming their fire at the older generation, pontificating their super-Left, sectarian views. The young members held that the New Masses, even while under the Carmon regime, was too immersed in a project of courting well-known, middle-class writers. From their perspective as outsiders to the literary establishment, even Mike Gold, the major proponent of “proletarian literature” in the United States, was objectionable. They griped that he was not very engaged with the John Reed Clubs and rarely came to a meeting. They thought that he was a prima donna, mainly preoccupied with Mike Gold, and more engrossed in winning big-name writers to Communism than in developing unknown revolutionary writers. Not only did they declare Gold an undisciplined Communist; they also concluded that his writing was ideologically weak. Jews without Money was knocked as petit-bourgeois, not proletarian, literature, and they reasoned that at times Gold seemed to be writing from the standpoint of the lumpen proletariat.11

Only a year after the clubs were formed, a capital donnybrook erupted when the Soviet-led International Union of Revolutionary Writers announced a meeting to be held in Kharkov in 1930. Gold received a personal invitation to attend and arranged for his friends, the novelists Josephine Herbst and John Herrmann, to receive payment for all their expenses so that they could accompany him as observers. The John Reed Clubs did not receive an invitation until later, as if it were an afterthought, and New York members were outraged at the favoritist way that Gold acquired accreditation for Herbst and Herrmann, since the two were at that point supposed to be merely fellow travelers. The previous antagonism the John Reed Club members felt toward Gold was thus exacerbated.

The Party’s point man in the clubs, Alexander Trachtenberg, agreed that the John Reed Clubs should be represented at such a momentous conference. When the clubs decided to send Harry Alan Potamkin (1900–1933) and William Gropper (1897–1977), neither of whom were then Party members, the Party fraction voted to add A. B. Magil to the delegation. The clubs were agreeable to this, and all three traveled together on a ship.12 As it turned out, Gold adhered to the literary views closest to those promoted by the conference. Like Gold, the International Union of Revolutionary Writers saw its project as winning established writers to a proletarian Communist perspective, not driving away middle-class writers and replacing them with self-proclaimed proletarian writers. In his “Notes from Kharkov” published in the New Masses, Gold stressed that the endeavor to activate the writing of proletarians was in no way to be counterpoised to the effort “to enlist all friendly intellectuals into the ranks of the revolution.”13

Further evidence of the erratic nature of the Party’s influence on the early New Masses is revealed in a letter from Carmon to Walter Snow, reacting to Snow’s political dissatisfactions with a New Masses review:

You are absolutely correct....I didn’t read the book of course. The review arrived before I had seen it. It was a mistake....and I can assure you that it is not going to happen again. That we have not been slaughtered by the movement for doing it is simply due to the fact that as yet the Party has not yet created the means by which such a necessary check up is made of its publications. So bloody anarchists like ourselves get away with murder.14

Consequently, in the first years of the Depression, Carmon’s free-wheeling, pragmatic managing of the New Masses, and Trachtenberg’s mechanical, politically motivated approach to decisions on cultural matters, represented both the past and the future of the Communist literary institutions that were pledged to realize “the Great Promise.” The Trachtenberg approach would grow steadfastly more commanding, at least until the political crisis brought on by the Khrushchev revelations in 1956, when for several years afterward there was a rethinking and something closer to an actual laissez-faire policy predominated. Between the contrary approaches of Carmon and Trachtenberg, however, the mediating process was complex and uneven. An investigation of the interplay among New Masses editorial board members–all of whom were pro-Communist, but who often dissented on how to run the magazine–permits some appreciation of the complicated elements that must be factored into any appreciation of the resulting public record.

In 1961 Stanley Burnshaw went to extraordinary lengths in a Sewanee Review essay to provide the historical context in which he had produced his 1935 New Masses commentary about Wallace Stevens, called “Turmoil in the Middle-Ground.”15 The review had elicited Stevens’s famous and much discussed “Mr. Burnshaw and the Statue,” which later became Part II of Stevens’s “Owl’s Clover,” reckoned by some critics to be his finest long poem. Yet Burnshaw noted in a letter to the editor of Sewanee Review that in twenty-five years not a single scholar of Wallace Stevens, or of poetry for that matter, had ever contacted him to request information about the episode, even though Burnshaw had become a highly visible poet, novelist, critic, and publisher after the 1940s.16 Interpretations of Burnshaw’s original argument, necessary to judge Stevens’s perception of it, were in Burnshaw’s estimation deduced from the general premises about Left criticism that emerged in later decades. Even though the participants in the affair were living, the famous exchange was not recreated and reconstituted in the terms appropriate to the writers in their own time. To clarify for the contemporary reader his aims and goals in the review, Burnshaw felt it indispensable to discuss his personal definition of Communism in the 1930s and thereafter, and the specific features of his divided state of mind as a poet and activist. He also provided six paragraph-long glosses on matters of terminology and tone, to allow the reader in the 1960s “to interpret the originating circumstances from within its period context.”17

Burnshaw’s point was that one cannot decipher the critical writings that appeared in the New Masses externally, from outside the elements at work in the system of relationships that produced the writings. At various times, the elements that inspired the Communist cultural movement included general policy turns emanating from Moscow; personal frictions among sensitive, egocentric, and ambitious editors; conflicts and resentments between editors closer to or further from the Party’s Political Bureau; and resentment between those who saw themselves as self-sacrificing and highly disciplined, and others they perceived as self-indulgent and bohemian. Sixty years later one can have little hope of recreating that fractious system of relationships with any completeness or guarantee of utter accuracy; but a look inside the editorial process, using memoirs, correspondence, and interviews as well as published material, may at least detach one from “the absurdity of the unhistorical view” about which Burnshaw was so aggrieved.18

In the 1950s, former New Masses editor Joseph Freeman asked former Communist Party chairman Earl Browder if he could put his finger on the date when pressure from the Party leadership and Moscow began to circumscribe Communist literary policy more directly. Browder “thought a moment and said, ‘After the assassination of Kirov,’” which had occurred in 1934.19 At first Freeman agreed with Browder, but later he found a 1931 memo documenting a major controversy between the New Masses and the John Reed Club of New York City. The strife, however, was not about the Party’s top-down control of the New Masses, but, rather, pertained to a state of affairs in which a group of Party members and their close allies in the club were endeavoring to secure their own hold on the publication. Still, the discord precipitated an intervention by the Party leadership, and Freeman saw this as a forerunner of later developments.

Conflicts at the New Masses, and interventions in the affairs of the magazine by the Party’s Political Bureau, seem to have eventuated about every two years after 1931, although one could retrospectively also include the predicament of the magazine in 1928, occasioned by an increasing irregularity of production and an impending financial collapse that Walt Carmon was asked to stem. Each emergency was linked to earlier ones, and usually several factors joined to create each new upset. The key dates of disruptive controversies prior to the McCarthy era are 1931–32, 1934, 1936, 1938, 1939– 40, 1945–46, and 1948. Through an investigation of the sequence of conflicts involving the New Masses during the 1930s and early 1940s from the point of view of members of the editorial staff, one may gain insight into the practical constraints of publishing a magazine that mediated between a Party organically linked to a Soviet-led global Communist movement, and an indigenous cultural rebellion that spawned its own personalities and concerns.

The first issue of the New Masses appeared in May 1926. Until September of 1933 it was published as a monthly. The issue of 2 January 1934 marked its debut as a weekly. Early sales figures are not accessible, but the magazine’s circulation enlarged from 6,000 as a monthly in late 1933 to 25,000 during its second year as a weekly in January 1935; at that juncture it was outselling the New Republic and had newsstand sales greater than both the New Republic and the Nation combined.20 It endured as a news and cultural weekly until March 1948, when it merged with the Communist Party’s literary publication Mainstream to reappear as Masses & Mainstream under the editorship of Samuel Sillen and Milton Howard.21

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, the New Masses did not really have an authoritative editor. While Mike Gold’s name was recorded in this capacity for several years, he was under siege by his critics in the John Reed Clubs and appeared at the editorial offices with less frequency after the 1920s. An editorial board did exist which appointed whoever was at hand and had time to work in the office to carry out editorial tasks in consultation with the board. The appointment of Whittaker Chambers in an editorial capacity in 1932, which has drawn attention due to his eventual role as a Soviet spy, was no doubt a more purposeful assignment but was still largely based on an assessment that Chambers had some open time as well as editorial ability. If Chambers chose to act like a “commissar” in trying to enforce a more orthodox, less literary, and more political orientation for the New Masses, this was due as much to Chambers’s temperament as Walt Carmon’s “anarchist” reign reflected his more haphazard predisposition.22

At the time of the 1931–32 conflict with John Reed Club members, Joseph Freeman believed that Joseph Pass (1893–1978), whom he saw as an ambitious but frustrated writer, wanted to replace Gold as editor of the New Masses and that illustrator William Gropper wanted to supplant artist Hugo Gellert (1892–1985).23 He also believed that Joseph North (born Joseph Soifer, 1904– 1976, a foremost Communist journalist and editor, and brother of composer Alex North), who would supersede Joseph Freeman as New Masses editor in the late 1930s, was pulling the strings.24 While the backers of the attempted coup were all members of the Party, or were at least pro-Party, the Party leadership, represented by Trachtenberg, had more confidence in Gold and Gellert. The result was a compromise establishing a “Relations Committee” after the fall 1931 blowout, which expanded the editorial board to include one representative each of the dissident writers and artists and held out the possibility that, in the future, the magazine might become the organ of the John Reed Clubs.25

Such was the state of the conflict between members of the John Reed Clubs and the New Masses at the time when Joseph Freeman returned from California in late 1931. Party leaders Earl Browder, Clarence Hathaway, and Alexander Trachtenberg then asked him to join the magazine’s editorial board. Assessing the situation, Freeman prepared a written report to the editorial board and the Party’s Political Bureau, urging a total reorganization of the publication and its staff, in order to “make it a magazine which a trained mind would listen to with respect and intellectual profit.”26

According to Freeman’s notes from the time, he was convinced that under Carmon the New Masses “was rotten with the worst characteristics of dilletantism. It tried to be ‘light,’ ‘humorous’–succeeded in being infantile and dull. While New Republic, Nation, etc., Modern Quarterly were publishing serious articles pretending to be Marxian, the New Masses insisted on running ‘proletarian’ but really bohemian stuff (lousy, crappy, were ‘Marxian’ terms).”27 Freeman’s harsh assessment, although it had some basis, was characteristic of his critique of the New Masses at every point when he had not been one of the leading editors. Throughout the 1930s he considered himself superior to his peer group (that is, those of his colleagues who were younger or less important than Trachtenberg, Jerome, or Browder); he saw himself as the most qualified to give the magazine direction and frequently insisted that most of its problems stemmed from a failure to heed his guidance.

No action was taken on his proposal, and the two-pronged crisis continued over the next year. Several new organizations, separate from the New Masses, emerged to meet the needs of Left-leaning professionals and writers; in particular, the League of Professionals for Foster and Ford, comprised of intellectuals supporting the Communist Party 1932 presidential campaign, and Pen and Hammer, an organization of Marxist academics that had its own publication.28 Meanwhile, the internal situation in the John Reed Club worsened. Thus a second conference between the Political Bureau and New Masses editors was held on 4 November 1932.

This conference set the stage for the removal of Carmon as de facto editor. His official departure in the early spring of 1932 was recalled by his widow as the result of a Party decision, although it was not due to any political disagreements. The Party leadership thought that Carmon “shouldn’t be editing the New Masses because he didn’t have a big enough name.” There were also myriad complaints about the quality of his editing from a professional point of view, and Carmon, whose personal life was additionally complicated by an affair with the magazine’s business manager, Frances Strauss, was close to a breakdown when he took a vacation in Florida in the winter of 1932. Mike Gold apparently opposed the decision to replace Carmon but lacked the will to fight it.29

The situation had still not reached the point where the Party leadership placed a markedly high priority on directing the New Masses editorial policy. The most professional journalist who joined the New Masses editorial board, serving from 1934 to 1938, and making possible its transformation into a weekly, was not a political appointee who enjoyed the designated trust of the Political Bureau. Herman Michelson was asked to join the board because he had a long history of working on newspapers, including the Socialist Call, the New York World, and the Herald Tribune. His skill was not in writing, of which he did little, but in his ability to focus on editing the work of others. Michelson was considered loyal to the Party, and he was the husband of a well-to-do Party stalwart, Clarina Michelson, but he was not regarded by the Party’s Political Bureau as politically shrewd.30

Joseph Freeman, who joined the board before Michelson, following the 1931 crisis, was also more respected for his professional skills than political leadership. His background in journalism included working in Europe in 1920 for the Chicago Tribune and New York Daily News, serving as associate editor of the Liberator during 1922–23, and handling the cables, mailers, analyses, and feature articles for TASS, the Soviet news agency in the United States, on and off from 1925 to 1931. Freeman had spent 1927 in the Soviet Union, where he sometimes worked as a translator for the Comintern. For a period in 1929 he was in Mexico as the TASS correspondent. Just before his assignment to the New Masses editorial board, he had briefly worked on a script in Hollywood. Freeman knew French, German, Spanish, and Russian and had published Dollar Diplomacy: A Study of American Foreign affairs (1925), coauthored with radical economist Scott Nearing, and Voices of October: Art and Literature in Soviet Russia (1930). His book The Soviet Worker: An Account of the Economic, Social and Cultural Status of Labor in the USSR would appear in 1932.31

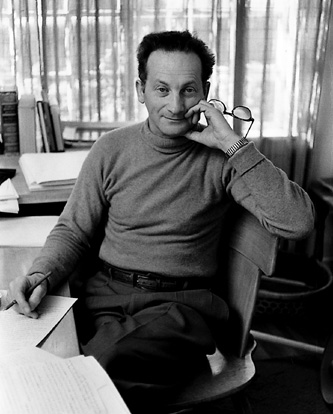

After 1932, the various appointments and assigned responsibilities were made with greater attention paid to an individual’s personal and political reliability. The Party’s leaders desired not so much individuals who would submit every word they wrote or every decision they made for inspection; to the contrary, they sought editors who could be trusted to make appropriate decisions on their own. For example, when the magazine became a weekly in 1934, Joseph North, who increasingly had the faith of the Party leadership, was assigned to the board. Stanley Burnshaw, who served on the New Masses editorial board from 1934 to 1936, thought of North, whom he respected for his knowledge of poetry and his piano playing, as “the political watchdog.” But Burnshaw, who refused to join the Party, and who believed that he held heterodox views on both Communism and literature, always felt that he had North’s full confidence.

In 1967, fifteen years after his total disillusionment with the Soviet Union and the Communist movement, Burnshaw recalled in a letter to New Left Marxist critic Lee Baxandall:

I was never bothered by so-called political pressure when I wrote for the New Masses: none that I can recall, and I have a good memory. Nor do I recall any inward pressures which my political self might have made me feel. I was about as free an agent in the New Masses as I have ever been. I said what I believed and that was that, and I can’t recall anything of mine having been corrected or revised or otherwise altered to suit anyone else.32

While it is always perilous to propose a “representative” figure, Burnshaw’s history in relation to the Communist-led cultural movement is particularly instructive because he never held Party membership, clandestine or otherwise. Yet Burnshaw was unequivocally part of the institutionalized leadership of a “movement” bound together by a common worldview cohering around a set of propositions that were the equivalent of a Communist outlook. To regard Burnshaw, and thousands like him, as not “Communist” because of their failure to pay fifty cent dues, is to miss apprehending the rudimentary glue of this remarkable movement. The bond can be fathomed less fittingly as top-down Party discipline than as elective affinity stemming from common longings, dreads, and experiences. Moreover, Burnshaw’s poetry, during and after his Communist period, resonates with the utopian urge emblematic of the revolutionary romantic inheritance that branded the early 1930s origins of the Left tradition.

Burnshaw was the son of Jewish immigrants from Russia who came to the United States in the late nineteenth century; he would picture their escape from Czarist oppression in his novel The Refusers (1981) and in his poetry published in Caged in an Animal’s Mind (1963).33 His father, who had earned a Ph.D. in philology at Columbia University, inaugurated his career as a teacher of Greek and Latin. His father’s dream, however, was to administer a home for Jewish orphans with a year-round curriculum combining academic and manual labor intended to produce a contemporary “Renaissance Man.” The elder Burnshaw launched his experimental school in New York City, then relocated to the rural setting of Pleasantville, twenty miles north of the city, when his son was six.

Throughout his youth, Burnshaw, who attended the experimental school, idealized his father’s learning and humanitarianism, and reveled in the surrounding pastoral countryside. Starting college at Columbia University, Burnshaw transferred to the University of Pittsburgh when his family moved to the city, graduating in 1925. He then wrote poetry while working for a steel corporation as an apprentice advertising copywriter in a nearby town. In the late 1920s he established a minor literary reputation with verse that appeared in the American Caravan, Midland Voices, Echo, Palms, his own magazine Poetry Folio, and in privately published editions. Simultaneously, he was profoundly aroused by the horrors of industrial life, both human and environmental, that he witnessed in the steel company town of Blawnox, Pennsylvania.

Burnshaw afterward ascertained that he had been transformed into both a communist and conservationist (in the sense of wishing to protect nature from the ravages of industrialism) by his dream that “the whole world would belong to the people.” He grasped this as an emotional rather than an intellectual development, one that became a kind of faith: “I had never had any political ideas in my life. This was an overwhelming apocalyptic conversion, and once I had it there was no question about it.”34

During a year spent in Europe with his first wife, where he studied at the University of Poitiers and the Sorbonne, he fell under the influence of the Jewish socialist French poet André Spire. Burnshaw returned to New York and began working as an advertising manager for the Hecht Company. In his auxiliary time, he pursued graduate work at New York University and later received an M.A. in English from Cornell. He joined V. F. Calverton’s journal Modern Quarterly as a contributing editor, married a second time, and worked on a book, eventually published as André Spire and His Poetry: Two Essays and Forty Translations (1933).35

The very week that Burnshaw returned from Europe he picked up a magazine at a New York newsstand that he had never seen before. It was the New Masses, and in its pages he read with rapture the spellbindingly original prose of a section of Mike Gold’s Jews without Money (1930). Burnshaw began submitting poetry and reviews to the New Masses, and eventually went to the magazine’s office to meet Gold in person.36 Soon he was following the Communist press, and, although he knew that the Party program did not address his fears about industry and technology, “the question disappeared under deepening waves of people victimized by the ever enlarging Depression.”37

In late 1933, Burnshaw first began working part-time and then full-time for the New Masses. As part of this association, he published an open letter breaking off relations with V. F. Calverton as “an enemy of the American working class” because Modern Monthly had published Max Eastman’s charges of repression of the arts in the Soviet Union. Burnshaw, in contrast, held that “all of the facts at my disposal clearly show that there is actually more freedom for artists in the Soviet Union than in any other country.”38

The Australian novelist Christina Stead remembered meeting the short and trim Burnshaw in the New Masses office at 31 East Twenty-Seventh Street in 1935: “a neat, limber young man with clear large appraising eyes. He might have been an Anatolian or other fresh-skinned country visitor from a distant place, considering the city ferment.”39 For Burnshaw, the New Masses years were more productive for his prose than for the kind of meditative poetry he aspired to write. In addition to his industrious editing, he completed a stream of reviews and essays for a number of publications; occasionally, when writing on political topics for the New Masses, he used the pen name “Jeremiah Kelley.”

Burnshaw’s essays and reviews of poetry were consistent in their content with the views of the Kharkov Conference. In “ ‘Middle-Ground’ Writers,” which appeared a few months prior to the advent of the Popular Front, Burnshaw declared that the task of the Marxist critic was to reach out to “every ally who can be enlisted.” While Burnshaw’s critical work promoted orthodox Communist politics (despite his private misgivings about the Party’s adulation of industrialization), he devoted greater attention to more strictly literary issues, and evidenced a commitment to convincing, not merely denouncing, writers who held “confused” or “wavering” positions that he characterized as “middle-ground.”40 During the later part of his tenure on the editorial board, he engaged in discussions with Joseph North about visiting Robert Frost (1874–1963) to discuss the idea of altering one of Frost’s poems that he had seen in manuscript, possibly for publication in the New Masses. Burnshaw felt some sort of rapprochement was conceivable after Frost praised Burnshaw for vanquishing Poetry editor Harriet Monroe (1860– 1936) in his 1934 debate with her about “Art and Propaganda.”41 Sometime later North or perhaps Alfred Kreymborg did approach Frost, but a negative New Masses review of Frost’s A Further Range (1936) by Rolfe Humphries apparently drove Frost away.42

Burnshaw was primarily responsible for selecting the poetry that appeared in the journal. His background was strong in modernism and his book on André Spire emphasized the virtues of free verse experimentalism. Nonetheless Burnshaw was in full agreement with the New Masses’ prioritization of publishing poetry that addressed social conditions, and his book reviews bluntly accused writers of producing escapist content; moreover, he saw no virtue in formal features as such. In a letter rejecting a poem submitted by the young Communist poet Willard Maas,43 Burnshaw criticized the poem for being “too chockful of startling imagery.” By this he meant that “instead of its being realized as a poem, it concentrates on arresting the attention, by its technical feats.”44 Burnshaw later denied that the selection of poems was politically determined by the New Masses editors. His denial, though, was slippery, in that he suggested that political “watch-dogging” simply wasn’t necessary. As the New Masses became increasingly perceived as the cultural arm of the Communist movement, writers who expressed views that differed from the movement, or who employed styles of which the movement seemed not to approve, were less likely to submit their work to the magazine.45

By 1936, Burnshaw was finding it difficult to write his own poised and contemplative poetry while carrying out his editorial responsibilities. He departed at the end of the year, primarily because of his unhappiness with the return of Joseph Freeman to the board, his financial problems, and uncertainty about his own creativity. The skillful anticapitalist poems he had been writing since the late 1920s appeared in the 1936 collection, The Iron Land: A Narrative; they were marked by a structural strategy of rhetorical questions and innovations. One that was selected for inclusion in the 1935 anthology Proletarian Literature in the United States suggests that, while it may be difficult to “play the violin when the house is on fire,” as his professor had warned him, one might perform quite well with alternative, louder instruments, such as trumpet and drum. In “I, Jim Rogers,” Burnshaw declaims his views in the kind of public voice that many on the Left thought necessary to answer the challenge of the “American Jeremiad”; that is, how and in what manner should a poet speak in the face of mass suffering.

Described as a “Mass Recitation for Speaker and Chorus,” the poem enables the diminutive Jewish intellectual Burnshaw to become “Jim Rogers,” the powerful voice of a de-ethnicized, “universal” working class, a personal witness to the devastation of unemployment in the Depression. Rogers, standing in line in a city relief office, watches a woman carrying a dead child–“the thing”–returning each day after being told the building is too crowded, refusing to recognize that her child lives no more. The strategy of the verse invokes the power of individual testimony to span the bridge of differential class experience and affect those who learn of suffering only from a safe distance:

I, Jim Rogers, saw her

and I can believe my eyes

And you had better believe me

Instead of the sugary lies

You read in the papers. I saw her

Slip into our waiting room

Among us thin blank men

And women waiting our turn.

But none of us looked like her

With her starved-in face, dazed eyes,

And the way she clung to the thing

Her arms pressed against her bosom.

When the woman is finally interviewed by the bureaucrats, she refuses to accept the loss of her child and flees into the city streets.

Jim Rogers then roams the passageways and alleys, picking up the fragments of her story. Her husband had lost his mill job in New Jersey after she became pregnant, and he committed suicide by jumping off a ferry. The woman then gave birth and found temporary work in a store basement, only to be fired because she was too weak to keep up the pace. While Rogers relates her tale in verse, he offers a pledge of solidarity as he elevates her as an example to humanity:

And if I

knew where to point my voice to

I’d yell out: Where are you? Answer!

Don’t run away!–Wait, answer!

Whom are you hiding from?

The miserly dog who fired you?

Listen: you’re not alone!

You’re never alone any more:

All of your brother-millions

(Now marking time) will stand by you

Once they have learned your tale!

The public voice by which Burnshaw breaks from the past to challenge the ruling order has completely overwhelmed the intimate inscriptions of his earlier work. In Burnshaw’s conclusion, Rogers, the proletarian surrogate through which the middle-class poet speaks, passionately attempts to galvanize passive observers into active agents; he turns to directly face the reader:

–If any of you who’ve listened,

See some evening walking

A frail caved-in white figure

That looks as if one time

It flowed with warm woman-blood.

See her ghosting the street

With a film of pain on her eyes,

Tell her that I, Jim Rogers,

Hold out whatever I own

A scrap of food, four walls–

Not much to give but enough

For rest and for arming the bones–

And a hard swift fist for defence

Against the dogs of the world

Ready to tear her down....

Tell her I offer this

In these days of marking time,

Tell our numberless scattered millions

In mill and farm and sweatshop

Straining with arms for rebellion,

Tie up our forces together

To salvage this earth from despair

And make it fit for the living.46

Rarely has the moral and political case for Communist solidarity been expressed so cleanly and eloquently.

Shortly after leaving the New Masses, Burnshaw entered the college textbook field. In May 1939, he founded the Dryden Press, where from time to time he hired friends from the Party to work in various capacities, such as translating and editing. Although he was troubled by Marxism’s ability to reveal social truth so well while failing to address crucial issues of human consciousness, emotion, and perception, Burnshaw still was friendly to the Party and to the Soviet Union, even at the time of the Hitler-Stalin Pact.47

In April 1940 Burnshaw’s year-old daughter died, leaving him in a state of deep depression. For five years he published almost nothing until his verse play, The Bridge, appeared in 1945. This was a political allegory reconsidering the role of technology in social progress, suggesting that art might possibly counter technology’s perversion by greed. Burnshaw was pleased when he learned that Mike Gold, whom he had always admired as the personification of socialist idealism, praised the play in the Daily Worker.48 Burnshaw also published a long poem that year, The Revolt of the Cats in Paradise (1945), and three years later a novel, The Sunless Sea (1948), both of which were satires suggesting a further devolution from his explicitly revolutionary position the 1930s.

Burnshaw’s disaffection from the Left was completed when he read about the anti-Semitic charges of a “Doctor’s Plot” against Stalin in the Soviet Union in 1951. When Granville Hicks gave anti-Communist testimony shortly thereafter, naming names before a government committee, Burnshaw sent him a supportive letter.49 He then announced a new, more philosophic poetic direction in Early and Late Testament (1952), which included revisions of his early poems in a way that tended to heighten their obscurity. Burnshaw added further to his reputation with his edition of The Poem Itself: Forty-Five Modern Poets in a New Presentation (1964) and his scholarly The Seamless Web: Language-Thinking, Creature-Knowledge, Art-Experience (1970). More of his novels and poems, increasingly on Jewish themes, appeared regularly through the 1980s.

Yet Burnshaw never repudiated his revolutionary past, which he defended with feistiness when queried in the 1960s and later by scholars who were seeking information about his old literary friends and associates. Moreover, from Burnshaw’s many reworkings of his earlier texts, there emerged a striking instance of utopian socialist verse, crystallizing in allegorical form the view of those who retained their communist dreams while losing hope as to the revolutionary means of realizing them. His poem “The Bridge,” echoing Hart Crane (as did Burnshaw’s 1945 play by that name), had appeared in a less developed form as Section Two of “Fifth Testament: Dialogue of the Heartbeat” in his 1952 collection Early and Late Testament. In the version published twenty years later, Burnshaw depicts in direct and clean free verse stanzas the efforts of an idealistic collective (“We”) to construct “a bridgehead from here and now to tomorrow,” reaching across the water, spanning a veritable sea, leaning “toward the far horizon,” with arms that “Reach out to greet the future.” The builders of Today work industriously in anticipation that from the other direction, Tomorrow, where they discern a “far light flooding,” will come a second bridgehead “with outstretched arms.” Then “the two bridgeheads may meet, the old and the new / Join hands to close the ocean.”

In the last stanza the builders are confronted with a doubter who sees no distant light and who questions that the “outstretched arms” will ever emerge from the other side. To this, the builders of Today reply:

We see it

Whether or not they range the air: half of whatever we see

Glows in cells not signaled by our eyes.

If men only lived by the things they knew

The skin of their hands could not touch, they would soon die

Of starved need. The shapes of sensate truth

Bristle with harshness. Eyeballs would cut the edges

Of naked fact and bleed. The thoughtful vision

Projected by our driving hope creates

A world where truth is possible: without it

The mind would break or die.50

Once he had made the case for Communist action in practical terms; now it is the dream alone that motivates a purposeful life.

As a non-Party member of the New Masses editorial board, Burnshaw was free to do as he pleased–no words of his were ever changed for political reasons–because, as he later recalled, “he would do no wrong.” Through his conversation and behavior, he convinced the other board members that, “like the others around him, he deeply believed in the necessity for promoting the Ultimate Good, whatever the circumstances,” which at that moment in history translated into defending the program of the Party.51

His relations with Party member Joseph North disclose additional aspects of Burnshaw’s political status. North gave books to Burnshaw to read, but he would never issue him orders. Still, it was clear that the Communist Party leadership put its trust in North more than Burnshaw. Not only did North seem to be someone who might serve as a “political watchdog” in case of trouble, but, unlike Burnshaw, he also made himself available to be moved to other assignments when needed. In fact, North soon left the magazine to begin editing the Weekly Section of the Daily Worker when Clarence Hathaway became the editor. After that North went to Spain, returning in 1938, to once again join the New Masses editorial board.

Burnshaw’s tenure at the New Masses essentially coincided with the moment when the old combination of anarchy and sectarianism that dominated the magazine was overthrown, and the views promoted by Mike Gold and the Kharkov Conference prevailed. And yet, not every editor was gratified by the new direction. Just prior to his own departure from the board in 1934, Joseph Freeman wrote in the New Masses that a “sectarian” attitude had dominated the Communist press until 1933. “As recently as last year it was easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a ‘fence-sitter’ to appear in the pages of the Communist press. The ‘line’ was jealousy guarded.” Suddenly, however, “fence-sitters” were happily embraced: “our press is his and he can say anything he likes, however remote it may be from revolutionary thought.”52 The first characterization seems exaggerated in light of the haphazardness of the Walt Carmon era; and the second seems to have been stuck in to give the impression of fairness and balance. Freeman is chiefly out to combat the Left of the movement but makes a preemptive strike to insulate himself from the insinuation that he conciliates fence-sitters.

As was the case with his 1931 report on the New Masses, Freeman’s 1934 statement may have been calculated to bolster his own position as a reliable guardian of orthodoxy, yet one who was open to reason–the perfect shepherd for the entrance of leftward-moving intellectuals into a Communist-led literary movement. In the next few paragraphs Freeman proceeded to denounce a “laissez-faire” attitude in the Party press, demanding that writers with a liberal past must now prove themselves Communists. Yet within this framework, he went on, writers who, during the last decade, were perfecting their craft but were now joining the revolutionary camp (John Howard Lawson and Isidor Schneider are mentioned) can come together with writers who had a decade of Communist loyalty (this seems to be a personal reference) and whose only need is to further perfect their craft.

Freeman, however, was probably not referring to a political laxity in the form or content of poetry or fiction so much as in articles and reviews that offered Marxist judgments; the magazine’s selection of imaginative literature does not appear to have been addressed in the early 1930s on a policy level, nor even subjected to much collective decision making. The testimony of Burnshaw suggests that the decisive factors influencing the publication of poetry and stories principally related to the kind of material submitted (which was already self-selected due to the frankly revolutionary and “proletarian culture” orientation of the “Third Period”) and the tastes of the particular editor who appears to have had free reign and was on occasion called the “poetry Czar.”53 Although a Party cultural leader like Trachtenberg or Jerome might promote the work of a certain writer, the areas in which the Party’s Political Bureau intervened mainly concerned matters such as professionalization of the publication and its distribution, personality conflicts, and the editors’ ability to carry out policy in a broad sense.

Such policy issues were especially acute at the beginning of the Popular Front, starting in mid-1935, and again after the crisis precipitated by the Hitler-Stalin Pact, in September 1939. In the first instance the Party leadership felt it could take another chance on Freeman; in the second, the more trusted Joseph North and A. B. Magil were put in charge. Freeman was already a bit of a political risk in 1936 because of the circumstances under which he had departed from the New Masses in 1934. He claimed in all of his letters to friends and in his public statements that he wanted to spend the next eighteen months working on his autobiographical An American Testament: A Narrative of Rebels and Romantics (1936). Yet in 1937 letter to Earl Browder he states that in 1934, after helping to transform New Masses into a weekly, he was kicked out “in a most uncomradely manner,” and that he was then subjected to gossip that he had abandoned the magazine at a crucial moment. What can be documented for certain is that Freeman had been involved in a major conflict with Herman Michelson, although Freeman claimed that he did not understand the basis of it.54

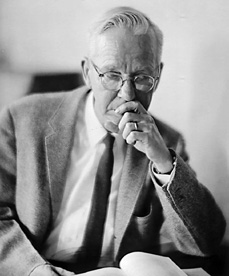

Before leaving the New Masses, however, Freeman asked Granville Hicks (1901–1982) to join the editorial board starting in January 1934. Hicks was a literature professor at Renssalaer Polytechnic Institute who had a year earlier published a Marxist history of literature in the United States, The Great Tradition (1933), and who would join the Communist Party a year later. Among others serving on the editorial board at the time of the Popular Front were Mike Gold, Joshua Kunitz, Herman Michelson, Joseph North, and the African American lawyer and journalist Loren Miller (1903–1967).55

Freeman rejoined the editorial board in March 1936 at the personal request of Browder, who asked him to step in for at least a year to pull the magazine out of crisis. He remained until mid-1937 when he was Officially disciplined by the Party for the first time, on the grounds of irresponsible personal and political behavior (see discussion in Chapter 5). During his tenure on the board throughout 1936 and 1937, numerous conferences about the direction of the New Masses were held between the editors and members of the Party’s Political Bureau.

The immediate problem that had to be addressed was a serious lack of financial resources. Many Left writers were now finding jobs in paid outlets in the publishing houses and magazines that had been closed down in 1932; new houses and magazines were being founded while older ones expanded. This reduced the number of active contributors. At the same time, the Party’s People’s Front orientation attracted many writers and professionals who were looking for a fresh venue to correspond to the changed times, not the same old predictable formulae. Moreover, the latest techniques of “bourgeois journalism”–manifest in Time and Esquire, and marked by innovative formats, layouts, condensed and witty presentations of material, and photographs–made the New Masses seem antiquated. Finally, the New Masses was trying to do too many things at once by publishing news, Marxist editorials, exposés, eye-witness accounts, theory, art, satire, and literature.

The magazine’s editors and the Party’s Political Bureau settled on the idea of publishing a new kind of Popular Front weekly with a Literary Supplement. On 29 December 1936,a staff conference was held at the New Masses office; invited guests included Alex Lehv of Soviet Russia Today and Herbert Kline of New Theater. The conference group concluded that the magazine should be a 64–72-page weekly with a colored cover and numbers of photographs aimed at achieving a circulation of at least 100,000.56

Committed to his own vision of what the magazine should be, Freeman had rejoined the New Masses that spring in a combative mood. In his characteristically hypercritical manner, he later recalled that “I returned to find that certain New Masses staffers were trying to cripple our literature by theories and practices which were sectarian and narrow-minded in middle-class rather than in proletarian cant.”57 Who exactly was to blame for this state of affairs is not specified, although the names of Burnshaw and North were soon missing from the editorial board. Hicks had moved on to an advisory capacity while working on his biography, John Reed (1936), and Isidor Schneider (1896–1977), a poet, novelist and prolific reviewer, joined the board. But since Schneider was to depart for the Soviet Union with a Guggenheim fellowship at the end of the year, he recommended a new young writer and Party member, F. W. Dupee (1904–1979), to temporarily take his place.58

Freeman wrote Granville Hicks that he hoped that, once finished with his book, Hicks might take a permanent position as the magazine’s literary editor. But Dupee’s work pleased Freeman, and Hicks, in the meantime, indicated that he preferred to serve the magazine in an advisory capacity from his home in upstate New York, contributing a “journal of the month.”59 Freeman was fearful that, if New Masses did not undergo a change that reflected the Popular Front orientation, it would be lost to the Communist movement as was Partisan Review (at that time in limbo, before its reappearance four months later with a semi-Trotskyist political inflection) and the recently defunct New Theater. Thus he plunged ahead with his concept of turning the magazine into a weekly like Time that would periodically feature a Literary Supplement. In late 1936, he traveled about the United States raising thousands of dollars to realize this goal.

A few months afterward, in the spring of 1937, Freeman planned, wrote the prospectus, and laid the foundation for the New Masses Literary Supplement which was to be published sometime later that year as an inserted magazine section coming with a New Masses subscription; the Supplement, he believed, would be the authentic heir of the original Masses, Liberator, and the early New Masses. Yet by the summer, with the Supplement still not available, he was in trouble with the Party leadership for other reasons and was asked by the Party’s Central Committee to leave the magazine. The reasons were that Freeman had not returned from a New Masses assignment in Mexico until many weeks after he was due home, and his 1936 autobiography had been criticized by high Soviet officials for gossipy indiscretions and for favorable references to exiled Bolshevik Leon Trotsky.

After the autumn of 1937, Freeman never returned to the New Masses office. The New Masses published a statement in its issue of 7 September 1937, claiming that, due to the dangerous international circumstances, Freeman “will leave shortly for a trip abroad in behalf of this magazine and a publisher who has commissioned him to do a book on the European situation.” The announcement promised that Freeman would continue to appear regularly in its pages through “a series of interviews from key points and with key personalities in Europe.”60 No such interviews ever appeared, although Freeman did publish some book reviews over the following months, one of which was a sectarian attack on critic Edmund Wilson. “Edmund Wilson’s Globe of Glass” explicitly defends the Stalin regime and attributes Wilson’s alleged faults to an attraction to Trotsky; thus the polemic appears to have some features of an effort on Freeman’s part to reestablish his own credentials as a Party loyalist.61 The masthead replaced his name as editor with that of his old antagonist, Herman Michelson, just returned from a long stay in the Soviet Union.

The Literary Supplement itself never lived up to Freeman’s expectations. In the months prior to its advent in December 1937, an altercation broke out between two of the supplement’s editors, Granville Hicks, the publication’s principal literary critic, and Horace Gregory, who was the core of an aggregation of Left-wing modern poets. Gregory had begun his teaching duties at Sarah Lawrence College in the fall of 1934, continuing his arm’s-length literary collaboration with the Party. With a background as a teacher and lecturer for the New York John Reed Club, Gregory had maintained his association with the Party throughout the transition to the Popular Front era; he joined the National Council as well as the Executive Committee of the League of American Writers in 1935, and signed the call for the Second Congress in 1937. Nevertheless, Gregory and his wife, poet Marya Zaturenska (1902–1982), had powerful convictions about their own superior abilities to judge verse, and an obsession bordering on paranoia about literary log-rolling in the establishment as well as in Left publications.

In the fall of 1937, Gregory launched his own book series, New Letters, to be issued twice a year by W. W. Norton and Company. The purpose of the first selection, presenting nearly forty poets and fiction writers from the United States and Western Europe, was primarily to feature “young writers . . . whose work has been deeply affected by a new conception of human consciousness which arose after the World War and began to be assimilated after 1930.”62 In private correspondence Gregory more directly referred to the younger writers in the collection as emerging out of the Communist cultural movement.63 Thus Gregory was taken aback when Granville Hicks launched a full-blown assault on the publication, under the title “Those Who Quibble, Bicker, Nag, and Deny,” in the 28 September 1937 issue of the New Masses.

Was this a personal attack motivated by malice and envy; or did it reflect genuine political differences, perhaps even an orthodoxy sponsored by the Party’s cultural leaders (Jerome and Trachtenberg)? Retrospectively, it seems that Popular Front culture, a product of both changing social conditions and of policies championed by influential Communist critics such as Hicks, operated on the terrain of a fairly precise contradiction. On the one hand, in the search for political and cultural allies against fascism, the yardstick of revolutionary purity no longer applied; the borders between Communism and New Deal liberalism became blurred, and popular writers who might earlier have been regarded as suspect due to their market orientation were embraced if the author and the cultural product seemed compatible with the antifascist crusade. On the other hand, there seemed to be much less tolerance for the atmosphere of despair characteristic of early Depression poetry and fiction, or of techniques and vocabularies that smacked of introspection, uncertainty, and ambivalence.

Granville Hicks, an English professor emerging from a devout Unitarian and Universalist church background, is aptly depicted by his biographers as possessing an “evangelical strain in [his] personality”; he also became a near-pristine example of the fellow traveler who exemplifies Enlightenment faith in rationality and progress.64 After several years of contributing to Communist publications primarily about fiction and criticism, he joined the Party in 1935, becoming a nationally recognized voice in letters for the politics and culture of the Popular Front. In Hicks’s address to the Second American Writers’ Congress, collected in a volume where poetry noticeably took a back seat, he exuded optimism and certainty while extolling the need for a literary leadership to create books that will “march in step with the marching feet of millions.”65 The orientation was accordant with Party general secretary Earl Browder’s call at the same congress for a literature “permeated with faith in the creative powers of the masses” with “one of its greatest themes [as] the dramatic world changes effected by mass creative power when it is organized, disciplined and directed.”66

In spite of the fact that Hicks had given the impression that he wanted to pull back from literary infighting when he refused the magazine’s post of literary editor under Freeman, there was no sign of magnanimity in his assault on fellow New Masses contributing editor Gregory’s volume. Obviously much of the writing anthologized by Gregory was an affront to the Popular Front sensibility championed by Hicks, but he may also have seen Gregory as a potential threat or rival, especially since the collection contained a piece of literary criticism by William Phillips and Philip Rahv that designated Hicks’s work as “more in the sectarian tradition of Upton Sinclair than in the great tradition of Karl Marx.”67 Two-thirds of the seventeen-paragraph-long essay was devoted to expanding on the theme that “Communism is good news,” and the condemnation of numerous writers, mostly already out of political favor (such as James T. Farrell and John Dos Passos), for delineating despair more than hopefulness. When he at last addressed the contents of New Letters, the contributors (many of whom had previously appeared in the New Masses) were arraigned for a Spenglerian bleakness and creating a mood more appropriate to the 1920s than the 1930s. “All this,” he closes, “confirms the impression that it is difficult to render in literature the substance of the Communist hope.”68

The rebuttal by Gregory and two other writers was introduced in a neutral tone by the New Masses editors in the issue of 12 October. Gregory, whose contribution was longest and appeared first, commenced by reminding Hicks that he had heard the call that “Communism is good news” first, as early as 1924. He then turned the tables and insisted that it was Hicks who was lost in the 1920s–the 1920s of H. L. Mencken. The evidence was that Hicks had displayed wild enthusiasm over Sinclair Lewis’s novel It Can’t Happen Here (1935)–which turned out to be a terrible misjudgment because Lewis “is now reported to be writing an anti-Communist play” and heading “straight in the direction of Leon Trotsky’s friends.” The problem was that “the actual center of Mr. Hicks’ review is a defense of a kind of realism that was ably practiced during the 1920s,” but which became “his only scale of measurement.” Searching for a poet “who would be a combination of Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson,” he failed to appreciate that “poetry is reviving under the stimulus of more than one literary tradition.” The issue dividing the two men was not that of enforcing a Communist Party political line–for both he and Hicks “believe that the U.S.S.R. is building an enduring civilization, and that Trotskyism is a disease”–but that Hicks was unable to read poetry.69

Muriel Rukeyser, closely allied with Gregory, more directly accentuated the topic of whether the “application of a rigid standard of the (moral) happy ending” was superior to a “sensitive straight facing of present scenes and values.” The real choice was between what is “inert” and what is “living.” Rukeyser did, in fact, find “hope” in the poems anthologized, but “a steadier, less blatant hope than Mr. Hicks demands–a hope to be worked for continually, not shouted before its time.”70 A third, brief intervention simply observed that the terms and categories of political action are improper for assessing lyric poetry.71

Hicks’s rejoinder acknowledged agreement with Gregory that “Communism is good news,” but exhorted that “most of our writers don’t make me feel that they know that in the very depths of their imagination.” Gregory had evaded the task of explaining whether or not he agrees with such a judgment, while Rukeyser had provided only a few unconvincing examples of a dubious “hope.” The other topics raised in passing–the decline of melody in poetry, alternatives to realism, the unique qualities of the lyric–were treated less dogmatically, and the reply ended with a call to continue the discussion.72

The next stage in the debate came in the form of an exchange between a young disciple of Gregory’s, T. C. Wilson (Theodore Carl Wilson, 1912–1950), a poet and critic equally facile in modernist and proletarian genres, and Samuel Sillen (1911–1973), a young New York University English instructor who had recently joined the New Masses board. Wilson proposed that the central issue in dispute was the “form” in which Communist hope was to be expressed, not the question of whether a particular group of writers was expressing it. Not only was “clear-headedness about the present” a superior criterion for literary judgment than “optimism about the future,” but the division itself was “critically meaningless,” since many outstanding works of art contain both. Hicks’s fixation on his formula led him to a basic error in equating the emotions expressed by writers in New Letters with the despair and bitterness of those of the 1920s: “What he significantly neglects to point out is that whereas the young writers of the twenties were generally content to express those emotions and stop at that, the young writers in Mr. Gregory’s collection, though they may convey a feeling of despair, also attempt to reveal its underlying causes.” Rather than succumb to the state of affairs producing despair, they demand that such conditions be changed.

The most literary-specific aspect of the interchange centered on realism and naturalism. Wilson reasoned that Marxism enabled the artist to command a more complex social vision than other worldviews, thereby requiring an extension of realism “to include perceptions and awareness impossible to convey within the confines of naturalist fiction.” Less consequential than the amassing of data (which Gregory had chastised as a feature of “pragmatic naturalism”) would be the “selection of significant fact”; documentation would remain vital but would be accomplished through “interpretation.” Moreover, in the new push to “render an object, a scene, an event, or character so that it will possess both a factual and symbolic meaning,” techniques such as the fable (already employed by Kafka, Henry James, Thomas Mann, and several Soviet writers) would be employed. The merit of such a technique should be judged by determining whether “the objective fact is made to stand as a symbol of some emotion, ideal, or belief that is larger than itself.”73

Wilson was rejoined by his contemporary, Sillen. Negotiating between what he posed as two extremes, Sillen affirmed that Hicks had neglected the necessity of multiformity, but noted that Wilson had made a more serious misjudgment in his claim that the “battle has now been won” in terms of rallying young writers to a “well-developed political consciousness” and “an intense hatred of fascism.” Wilson was mistaking the status of a minority, and one “on the offensive,” for the larger milieu of cultural workers who had not yet heard the “good news.” This suggested that Wilson was in some cases mistaking claims of Marxist commitment for their actuality–a sloppy procedure that was particularly dangerous in light of the attraction for some intellectuals of Trotskyist pretenses to being pro-socialist or anti-fascist. The task of the literary critic was not to extol political consciousness in a general sense but to separate “the genuine from the spurious.”

Wilson also erred in his promotion of fables, especially those of Kafka, as far surpassing the realist tradition. Realism must be flexible, and certainly not bound to naturalism; but Sillen saw the American tradition of realism in the category of “great historical sources,” while the fables of Kafka and James were at best “enriching streams” to be subsumed into the larger project. To Wilson’s endorsement of Kenneth Burke’s critical work Attitudes Toward History (1937), Sillen counterpoised the volume by the British Spanish Civil War writer Ralph Fox, The Novel and the People (1937).74

On 7 November 1937, the first Literary Supplement appeared. The four editors were Gold, Gregory, Hicks, and Joshua Kunitz (1897–1980). The hindmost was a serious scholar who had traveled around the Soviet Union and had written a Ph.D. dissertation at Columbia University, published as Russian Literature and the Jew.75 Kunitz was among the most highly educated Communist intellectuals and the Party’s undisputed authority on Russian literature. Sometimes Kunitz was called upon to defend controversial Soviet policy, as in the case of the Moscow Trials. Yet he was not thoroughly trusted by the Party leadership.

In the early 1930s Kunitz wrote for the New Masses as “J. Q. Neets,” and was considered a Party member even though for years he never attended a meeting. He was a more active presence in the John Reed Clubs, where he was outspoken in defense of the importance of literary style, and happy to debate comrades such as Mike Gold and Henry George Weiss, who, in his view, failed to appreciate the culture of the past.76 Then Kunitz was spotted talking to the novelist Edward Dahlberg (1900–1977) after Dahlberg had broken with the Party. When reprimanded, Kunitz testily replied, “I’ll talk to whom I please.” He subsequently agreed to leave the Party of his own accord, and, although he habitually contributed to the Party press, he was regarded behind his back by some Party leaders as a “Menshevik.”77 Nevertheless, he continued to write for publications associated with the Communist movement until the late 1970s. In the intervening years he published many books, including Dawn over Samarkand (1930), Russia: The Giant That Came Last (1947), and Russian Literature since the Revolution (1948). He also taught at academic institutions such as the City College of New York, Cornell University, and Middlebury College until he was blacklisted at the beginning of the Cold War.

In line with the special prerogative of each critic, Hicks contributed an essay to the supplement exposing the “Trotskyism” of the Nation magazine’s book-review section, while Gregory extolled the virtues of diverse literary techniques in his review, “Poetry in 1937.” Verse by Rukeyser, British Communist Hugh MacDiarmid (1892–1978), and several others was published, ranging from the moderate difficulty of the former to the more conventional forms and explicit content of the latter.

Within a few weeks, the New Masses editors published an editorial, “Is Poetry Dead?,” referring to a debate held in Toledo, Ohio, between an English professor and a CIO organizer. The former insisted that the public no longer cared for verse; the latter maintained that, while the American people had lost interest in poets “who were obsessed with images of death and decay,” the rebirth of the labor movement had produced a vital interest in poetry “in the tradition of Whitman” that “talks the language of the people.” The editorial called for readers, including poets, to take sides–to explain which writers are “reaching large audiences,” and the reasons.78

The terms in which the issue was posed could hardly do less than elicit the most anti-intellectual sentiments; who, after all, would wish to join the bourgeois professor against the idealistic worker, or stand on the side of “death and decay” against “the language of the people”? In the second Literary Supplement (now retitled “Literary Section” due to a post office requirement), two letters were published in response, both castigating the verse of Rukeyser for its amorphousness and lack of verbs. One of the authors, folk-singer Lee Hays (1914–1981), further indicted James Agee, Richard Eberhart, and other New Masses contributors for “regurgitation of their own lives.” His recommendation was to “let Horace Gregory sell the Daily Worker on the subway for a year if he doesn’t know what I mean.” Hays then concluded, “I sometimes wish Uncle Mike Gold would rise and slay these demons for us, for he is a sensible voice crying in what appears to be a wilderness of ivory towers.”79 Indeed, Gold himself had recently been embroiled in a parallel debate in the New Masses around the legacy of Isadora Duncan (1878–1927) in relation to modern dance in the 1930s. In his depreciation of the latter, Gold used every opportunity to take swipes at the influence of T. S. Eliot and “deliberately unintelligible and overtechnicalized” modern poetry. He concluded with the statement that “in our revolutionary poetry and dance I would like to see more beauty and romanticism–the sort one finds in all folk ballads, for instance. I just don’t like cerebral art, and don’t believe I ever will.”80

The second edition of the Literary Section, itself, noteworthy for the initial appearance of novelist Thomas Wolfe (1900–1938) in a Communist venue, contained little poetry–only a short piece by Party member David Wolfe (a pseudonym for future screenwriter Ben Maddow [1909–1992]), and translations of Federico Garcia Lorca by Langston Hughes. The sole essay addressing poetry was an academic piece by future English scholar Dorothy Van Ghent (1907–1967), then a Ph.D. candidate at Berkeley and the lover of poet Kenneth Rexroth. She surveyed trends in modern poetry and called for a “dialectical materialist” attitude among Marxist poets.81

A few weeks later, Martha Millet (b. 1919), a teenage Communist who identified herself as secretary of the “Poetry Group,” joined the discussion on the side of the CIO activist and against the recent verse publications of the New Masses. Her organization advocated poetry that was not “confusedly ornate, pretentiously intellectual, and ‘cerebrally’ dull.” The essence of poetry was rhythm, “an aspect of power, including political power,” demonstrated by the efficacy of the slogan “workers of the world, unite.” Therefore, “The Popular Front needs rhythms...in order to combat the profit system.” Although high standards were necessary, “the popular front has to become popular,” mandating that “poetry has to become popular.” Moreover, the key to popularity is when verse “attains a rich and accurate simplicity and directness.”82

In the following week the New Masses printed a purported survey of the 389 poems published in the poetry journal Westward, which were simplistically classified as “Descriptive Poetry,” “Poetry of Frustration,” and so forth. The surveyor concluded that 85 percent of the poems were “worthless,” from the viewpoint of subject matter.83 The following page offered yet another letter on the poetry debate, this time endorsing Lee Hays’s call for Mike Gold to take action against cerebral poets, to which he should also add critics such as Dorothy Van Ghent.84 A week later, Robert Forsythe (a pseudonym for Kyle Crichton [1896–1960], a well-known writer for Collier’s magazine) used his column, “Forsythe’s Page,” to enter the fray. Under the rubric “Wanted: Great Songs,” he urged novelists to produce novels that were “simple, eminently readable,” such as those of John O’Hara and James M. Cain. As for poets, the priority should be ballads in the vein of Robert Burns’s “A Man’s a Man for A’ That.” Forsythe urged that Lee Hayes and others should be heeded as nothing less than the voices of “workers [who were] protesting that the poems which appear in the New Masses mean nothing to them.” In his own way, Forsythe was frankly acknowledging that art must be subordinated to the requirements of “living in a state of emergency.” He explained that publishing the work of a “second-rate poet” was of no consequence because “I want the struggling people of this world to have all the help they can get....Perhaps this is a period in history when survival is more important than art.” What was imperative, then, was “a poem that will set me cheering...a new revolutionary song that will set my heart afire.”85

After this, the now one-sided debate subsided. Moreover, with the appearance of the third Literary Section on 8 February 1938 devoted entirely to the translation of a Japanese novelette, the New Masses announced a major financial crisis; the editors appealed for $20,000 partly due to the added expense of the supplement. Urgent appeals continued throughout March. When the fourth supplement appeared on 12 April, the only poetry in it was a forty-stanza long anti-Trotskyist satirical ballad by Granville Hicks called “Revolution in Bohemia.”86 Gregory’s name remained listed as an editor of the Literary Section and contributing editor of the journal, but the voices of himself and those with his perspective had nearly vanished.

A fuller understanding of the public debate can be obtained by examining private correspondence of the same months. In November 1937, Gregory confided to T. C. Wilson in Columbus, Ohio, that he had joined the board of the New Masses Literary Supplement with the idea that, when Wilson returned to Manhattan, the younger man might simply take over Gregory’s position. But now that Wilson was delayed, Gregory felt beleaguered by Hicks, Gold, and Joshua Kunitz; moreover, the future of New Letters was in crisis due to the conversion to Trotskyism of his assistant, fiction writer Eleanor Clark.87 In an earlier letter, Gregory had explained that those opposed to him also included “the bourgeois Left,” by which he meant the New Republic and its literary editor Malcolm Cowley (1898–1989), whom he believed to be a master at planting reviews to reflect his prejudices. Nevertheless, Gregory was convinced that the controversy over New Letters would lead to a whole “new phase” of the cultural movement.88

Over the next few months Gregory’s aspirations were scaled down. He began to write to Wilson that his success had been mainly in keeping Hicks from “taking over full charge of the literary section.”89 Next he announced that he had decided to give up on New Letters, convinced that Clark was sabotaging its promotion in order to force Gregory to turn for help to the newly reorganized, and semi-Trotskyist, Partisan Review. By now he wanted out of New Masses as well: “The whole weary fight...is a fight for power.” Gregory saw himself under attack by the New York literary establishment, the Communists, the Trotskyists, and the conservatives. Some of the resentment, he believed, was simply against “new writing, not a personal resentment but the general feeling of POWER slipping. The old babies on all fronts grow frightened at the large number of new names I have published within the last two years.” Instead of his efforts fomenting a new movement in poetry, Gregory had come to realize that only Wilson and Rukeyser would openly back his position.90

Another angle on the dispute can be seen in the correspondence between Samuel Sillen and Wilson. While Wilson was thoroughly under Gregory’s influence, to the point where he often sent advance copies of his reviews and letters to the older man for coaching before submission, Sillen nonetheless opened the New Masses door wide to Wilson’s participation. To Ohio, Sillen sent letters praising Wilson’s essays in the New Masses and Yale Review, inviting him to New York for discussions of their differences, appealing to Wilson to submit poetry, book reviews, and literary essays.91 As tensions increased and Gregory continued to mail Wilson venomous reports about the allegedly poor quality of the new Literary Section, Sillen continued to answer Wilson’s queries and protests with patience.

Sillen pointed to the concerted effort made by the New Masses editors to give book reviews to individuals thought to be sympathetic to the particular school of literature (such as the assignment of works by the Auden Group in England to Wilson himself). He also emphasized that the opinions of various columnists were theirs alone. He claimed (less convincingly) that the “Is Poetry Dead?” editorial was not an attack on Gregory, but that the contents of the letters that arrived did show an unsympathetic attitude to certain kinds of writing among the readership that could not be neglected. Moreover, he insisted that of the hundreds of poems that arrived every week at the New Masses office, most were of truly poor quality; the few that made it into print were simply the best of what they received, not selected because they were of the “oompah” (cheerleading and optimistic) type. His last communication ended with an unrequited plea:

We want the best that we can get. When gifted writers like yourself refrain from giving it to us, our battle is tougher, no doubt, but we keep on going. You have again and again been invited to write for the magazine. You have been published in it. At no time was your stuff blue-pencilled into vulgarity. If you want a better magazine you’ve got to chip in and help. Nothing else will do.92

Wilson, however, was finished; Gregory remained in name only; Rukeyser, who had other connections to the movement beyond the New Masses, donated an occasional review.