In some cases, it’s easy to start writing tests for a class. But in legacy code, it’s often difficult. Dependencies can be hard to break. When you’ve made a commitment to get classes into test harnesses to make work easier, one of the most infuriating things that you can encounter is a closely scattered change. You need to add a new feature to a system, and you find that you have to modify three or four closely related classes. Each of them would take a couple of hours to get under test. Sure, you know that the code will be better for it at the end, but do you really have to break all of those dependencies individually? Maybe not.

Often it pays to test “one level back,” to find a place where we can write tests for several changes at once. We can write tests at a single public method for changes in a number of private methods, or we can write tests at the interface of one object for a collaboration of several objects that it holds. When we do this, we can test the changes we are making, but we also give ourselves some “cover” for more refactoring in the area. The structure of code below the tests can change radically as long as the tests pin down their behavior.

How do we get these “covering tests” in place? The first thing that we have to figure out is where to write them. If you haven’t already, take a look at Chapter 11, I Need to Make a Change. What Methods Should I Test? That chapter describes effect sketches (155), a powerful tool that you can use to figure out where to write tests. In this chapter, I describe the concept of an interception point and show how to find them. I also describe the best kind of interception points you can find in code, pinch points. I show you how to find them and how they can help you when you want to write tests to cover the code you are going to change.

An interception point is simply a point in your program where you can detect the effects of a particular change. In some applications, finding them is tougher than it is in others. If you have an application whose pieces are glued together without many natural seams, finding a decent interception point can be a big deal. Often it requires some effect reasoning and a lot of dependency breaking. How do we start?

The best way to start is to identify the places where you need to make changes and start tracing effects outward from those change points. Each place where you can detect effects is an interception point, but it might not be the best interception point. You have to make judgment calls throughout the process.

Imagine that we have to modify a Java class called Invoice, to change the way that costs are calculated. The method that calculates all of the costs for Invoice is called getValue.

public class Invoice

{

...

public Money getValue() {

Money total = itemsSum();

if (billingDate.after(Date.yearEnd(openingDate))) {

if (originator.getState().equals("FL") ||

originator.getState().equals("NY"))

total.add(getLocalShipping());

else

total.add(getDefaultShipping());

}

else

total.add(getSpanningShipping());

total.add(getTax());

return total;

}

...

}

We need to change the way that we calculate shipping costs for New York. The legislature just added a tax that affects our shipping operation there, and, unfortunately, we have to pass the cost on to the consumer. In the process, we are going to extract the shipping cost logic into a new class called ShippingPricer. When we’re done, the code should look like this:

public class Invoice

{

public Money getValue() {

Money total = itemsSum();

total.add(shippingPricer.getPrice());

total.add(getTax());

return total;

}

}

All of that work that was done in getValue is done by a ShippingPricer. We’ll have to alter the constructor for Invoice also to create a ShippingPricer that knows about the invoice dates.

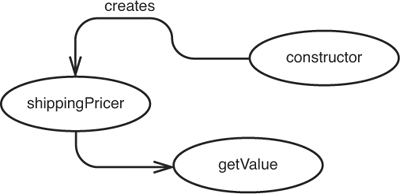

To find our interception points, we have to start tracing effects forward from our change points. The getValue method will have a different result. It turns out that no methods in Invoice use getValue, but getValue is used in another class: The makeStatement method of a class named BillingStatement uses it. This is shown in Figure 12.1.

Figure 12.1 getValue affects BillingStatement.makeStatement.

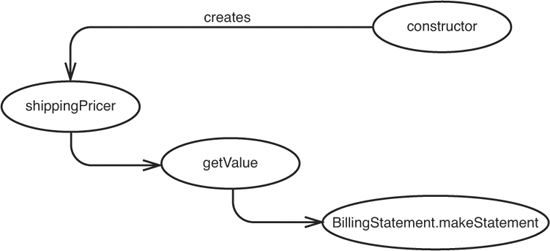

We’re also going to be modifying the constructor, so we have to look at code that depends on that. In this case, we’re going to be creating a new object in the constructor, a ShippingPricer. The pricer won’t affect anything except for the methods that use it, and the only one that will use it is the getValue method. Figure 12.2 shows this effect.

Figure 12.2 Effects on getValue.

We can piece together the sketches as in Figure 12.3.

Figure 12.3 A chain of effects.

So, where are our interception points? Really, we can use any of the bubbles in the diagram as an interception point here, provided that we have access to whatever they represent. We could try to test through the shippingPricer variable, but it is a private variable in the Invoice class, so we don’t have access to it. Even if it were accessible to tests, shippingPricer is a pretty narrow interception point. We can sense what we’ve done to the constructor (create the shippingPricer) and make sure that the shippingPricer does what it is supposed to do, but we can’t use it to make sure that getValue doesn’t change in a bad way.

We could write tests that exercise the makeStatement method of BillingStatement and check its return value to make sure that we’ve made our changes correctly. But better than that, we can write tests that exercise getValue on Invoice and check there. It might even be less work. Sure, it would be nice to get BillingStatement under test, but it just isn’t necessary right now. If we have to make a change to BillingStatement later, we can get it under test then.

In most cases, the best interception point we can have for a change is a public method on the class we’re changing. These interception points are easy to find and easy to use, but sometimes they aren’t the best choice. We can see this if we expand the Invoice example a bit.

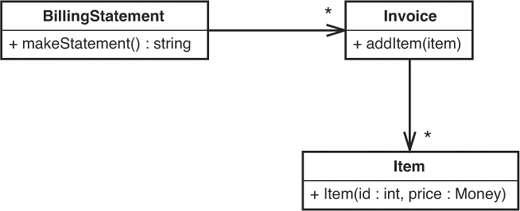

Let’s suppose that, in addition to changing the way that shipping costs are calculated for Invoices, we have to modify a class named Item so that it contains a new field for holding the shipping carrier. We also need a separate per-shipper breakdown in the BillingStatement. Figure 12.4 shows what our current design looks like in UML.

Figure 12.4 Expanded billing system.

If none of these classes have tests, we could start by writing tests for each class individually and making the changes that we need. That would work, but it can be more efficient to start out by trying to find a higher-level interception point that we can use to characterize this area of the code. The benefits of doing this are twofold: We could have less dependency breaking to do, and we’re also holding a bigger chunk in the vise. With tests that characterize this group of classes, we have more cover for refactoring. We can alter the structure of Invoice and Item using the tests we have at BillingStatement as an invariant. Here is a good starter test for characterizing BillingStatement, Invoice, and Item together:

void testSimpleStatement() {

Invoice invoice = new Invoice();

invoice.addItem(new Item(0,new Money(10));

BillingStatement statement = new BillingStatement();

statement.addInvoice(invoice);

assertEquals("", statement.makeStatement());

}

We can find out what BillingStatement creates for an invoice of one item and change the test to use that value. Afterward, we can add more tests to see how statement formatting happens for different combinations of invoices and items. We should be especially careful to write cases that exercise areas of the code where we’ll be introducing seams.

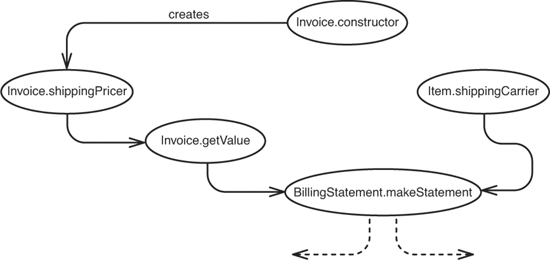

What makes BillingStatement an ideal interception point here? It is a single point that we can use to detect effects from changes in a cluster of classes. Figure 12.5 shows the effect sketch for the changes we are going to make.

Figure 12.5 Billing system effect sketch.

Notice that all effects are detectable through makeStatement. They might not be easy to detect through makeStatement, but, at the very least, this is one place where it is possible to detect them all. The term I use for a place like this in a design is pinch point. A pinch point is a narrowing in an effect sketch (155), a place where it is possible to write tests to cover a wide set of changes. If you can find a pinch point in a design, it can make your work a lot easier.

The key thing to remember about pinch points, though, is that they are determined by change points. A set of changes to a class might have a good pinch point even if the class has multiple clients. To see this, let’s take a wider look at the invoicing system in Figure 12.6.

Figure 12.6 Billing system with inventory.

We didn’t notice it earlier, but Item also has a method named needsReorder. The InventoryControl class calls it whenever it needs to figure out whether it needs to place an order. Does this change our effect sketch for the changes we need to make? Not a bit. Adding a shippingCarrier field to Item doesn’t impact the needsReorder method at all, so BillingStatement is still our pinch point, our narrow place where we can test.

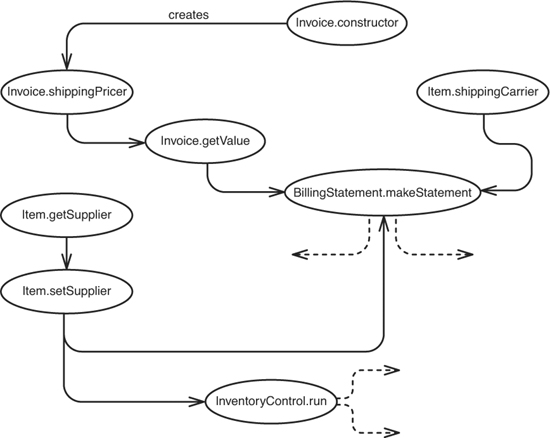

Let’s vary the scenario a bit more. Suppose that we have another change that we need to make. We have to add methods to Item that allow us to get and set the supplier for an Item. The InventoryControl class and the BillingStatement will use the name of the supplier. Figure 12.7 shows what this does to our effect sketch.

Figure 12.7 Full billing system scenario.

Things don’t look as good now. The effects of our changes can be detected through the makeStatement method of BillingStatement and through variables affected by the run method of InventoryControl, but there isn’t a single interception point any longer. However, taken together, the run method and the makeStatement method can be seen as a pinch point; together they are just two methods, and that is a narrower place to detect problems than the eight methods and variables that have to be touched to make the changes. If we get tests in place there, we will have cover for a lot of change work.

In some software, it is pretty easy to find pinch points for sets of changes, but in many cases it is nearly impossible. A single class or method might have dozens of things that it can directly affect, and an effect sketch drawn from it might look like a large tangled tree. What can we do then? One thing that we can do is revisit our change points. Maybe we are trying to do too much at once. Consider finding pinch points for only one or two changes at a time. If you can’t find a pinch point at all, just try to write tests for individual changes as close as you can.

Another way of finding a pinch point is to look for common usage across an effect sketch (155). A method or variable might have three users, but that doesn’t mean that it is being used in three distinct ways. For example, suppose that we need to do some refactoring of the needsReorder method of the Item class in the previous example. I haven’t shown you the code, but if we sketched out effects, we’d see that we can get a pinch point that includes the run method of InventoryControl and the makeStatement method of BillingStatement, but we can’t really get any narrower than that. Would it be okay to write tests at only one of those classes and not the other? The key question to ask is, “If I break this method, will I be able to sense it in this place?” The answer depends on how the method is used. If it is used the same way on objects that have comparable values, it could be okay to test in one place and not the other. Work through the analysis with your coworker.

In the previous section, we talked about how useful pinch points are in testing, but they have other uses, too. If you pay attention to where your pinch points are, they can give you hints about how to make your code better.

What is a pinch point, really? A pinch point is a natural encapsulation boundary. When you find a pinch point, you’ve found a narrow funnel for all of the effects of a large piece of code. If the method BillingStatement.makeStatement is a pinch point for a bunch of invoices and items, we know where to look when the statement isn’t what we expect. The problem then has to be because of the BillingStatement class or the invoices and items. Likewise, we don’t need to know about invoices and items to call makeStatement. This is pretty much the definition of encapsulation: We don’t have to care about the internals, but when we do, we don’t have to look at the externals to understand them. Often when I look for pinch points, I start to notice how responsibilities can be reallocated across classes to give better encapsulation.

Writing tests at pinch points is an ideal way to start some invasive work in part of a program. You make an investment by carving out a set of classes and getting them to the point that you can instantiate them together in a test harness. After you write your characterization tests (186), you can make changes with impunity. You’ve made a little oasis in your application where the work has just gotten easier. But be careful—it could be a trap.

We can get in trouble in a couple of ways when we write unit tests. One way is to let unit tests slowly grow into mini-integration tests. We need to test a class, so we instantiate several of its collaborators and pass them to the class. We check some values, and we can feel confident that the whole cluster of objects works well together. The downside is that, if we do this too often, we’ll end up with a lot of big, bulky unit tests that take forever to run. The trick when we are writing unit tests for new code is to test classes as independently as possible. When you start to notice that your tests are too large, you should break down the class that you are testing, to make smaller independent pieces that can be tested more easily. At times, you will have to fake out collaborators because the job of a unit test isn’t to see how a cluster of objects behaves together, but rather how a single object behaves. We can test that more easily through a fake.

When we are writing tests for existing code, the tables are turned. Sometimes it pays to carve off a piece of an application and build it up with tests. When we have those tests in place, we can more easily write narrower unit tests for each of the classes we are touching as we do our work. Eventually, the tests at the pinch point can go away.

Tests at pinch points are kind of like walking several steps into a forest and drawing a line, saying “I own all of this area.” After you know that you own all of that area, you can develop it by refactoring and writing more tests. Over time, you can delete the tests at the pinch point and let the tests for each class support your development work.