Stepping into unfamiliar code, especially legacy code, can be scary. Over time, some people become relatively immune to the fear. They develop confidence from confronting and slaying monsters in code over and over again, but it is tough not to be afraid. Everyone runs into demons that they can’t slay from time to time. If you dwell on it before you start to look at the code, that makes it worse. You never know whether a change is going to be simple or a weeklong hair-pulling exercise that leaves you cursing the system, your situation, and nearly everything around you. If we understood everything we need to know to make our changes, things would go smoother. How can we get that understanding?

Here’s a typical situation. You find out about a feature that you need to add to the system. You sit down and you start to browse the code. Sometimes you can find out everything you need to know quickly, but in legacy code, it can take some time. All the while, you are making a mental list of the things you have to do, trading off one approach against another. At some point, you might feel like you are making progress and you feel confident enough to start. In other cases, you might start to get dizzy from all of the things that you are trying to assimilate. Your code reading doesn’t seem to be helping, and you just start working on what you know how to do, hoping for the best.

There are other ways of gaining understanding, but many people don’t use them because they are so caught up in trying to understand the code in the most immediate way that they can. After all, spending time trying to understand something looks and feels suspiciously like not working. If we can get through the understanding bit very fast, we can really start to earn our pay. Does that sound silly? It does to me, too, but often people do act that way—and it’s unfortunate because we can do some simple, low-tech things to start work on a more solid footing.

When reading through code gets confusing, it pays to start drawing pictures and making notes. Write down the name of the last important thing that you saw, and then write down the name of the next one. If you see a relationship between them, draw a line. These sketches don’t have to be full-blown UML diagrams or function call graphs using some special notation—although, if things get more confusing, you might want to get more formal or neater to organize your thoughts. Sketching things out often helps us see things in a different way. It’s also a great way of maintaining our mental state when we are trying to understand something particularly complex.

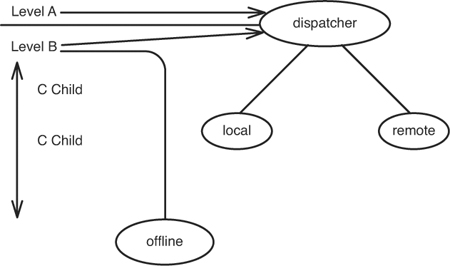

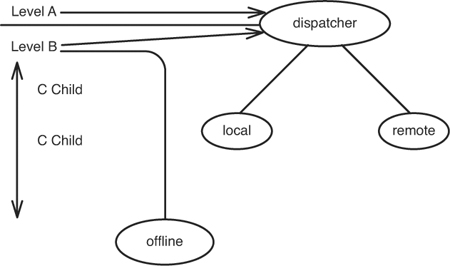

Figure 16.1 is a re-creation of a sketch that I drew with another programmer the other day as we were browsing code. We drew it on the back of a memo (the names in the sketch have been changed to protect the innocent).

The sketch is not very intelligible now, but it was fine for our conversation. We learned a bit and established an approach for our work.

Doesn’t everyone do this? Well, yes and no. Few people use it frequently. I suspect that the reason is because there really isn’t any guidance for this sort of thing, and it’s tempting to think that every time we put pen to paper, we should be writing a snippet of code or using UML syntax. UML is fine, but so are blobs and lines and shapes that would be indecipherable to anyone who wasn’t there when we drew them. The precision doesn’t have to be on paper. The paper is just a tool to make conversation go easier and help us remember the concepts we’re discussing and learning.

The really great thing about sketching parts of a design as you are trying to understand them is that it is informal and infectious. If you find this technique useful, you don’t have to push for your team to make it part of its process. All you have to do is this: Wait until you are working with someone trying to understand some code, and then make a little sketch of what you are looking at as you try to explain it. If your partner is really engaged in learning that part of the system too, he or she will look at the sketch and go back and forth with you as you figure out the code.

When you start to do local sketches of a system, often you are tempted to take some time to understand the big picture. Take a look at Chapter 17, My Application Has No Structure, for a set of techniques that make it easier to understand and tend a large code base.

Sketching isn’t the only thing that aids understanding. Another technique that I often use is listing markup. It is particularly useful with very long methods. The idea is simple and nearly everyone has done it at some time or another, but, frankly, I think it is underused.

The way to mark up a listing depends on what you want to understand. The first step is to print the code that you want to work with. After you have, you can use listing markup as you try to do any of the following activities.

If you want to separate responsibilities, use a marker to group things. If several things belong together, put a special symbol next to each of them so that you can identify them. Use several colors, if you can.

If you want to understand a large method, line up blocks. Often indentation in long methods can make them impossible to read. You can line them up by drawing lines from the beginnings of blocks to the ends, or by commenting the ends of blocks with the text of the loop or condition that started them.

The easiest way to line up blocks is inside out. For instance, when you are working in one of the languages in the C family, just start reading from the top of the listing past each opening brace until you get to the first closing brace. Mark that one and then go back and mark the one that matches it. Keep reading until you get to the next closing brace, and do the same thing. Look backward until you get to the opening brace that matches it.

If you want to break up a large method, circle code that you’d like to extract. Annotate it with its coupling count (see Chapter 22, I Need to Change a Monster Method and I Can’t Write Tests for It).

If you want to understand the effect of some change you are going to make, instead of making an effect sketch (155), put a mark next to the code lines that you are going to change. Then put a mark next to each variable whose value can change as a result of that change and every method call that could be affected. Next, put marks next to the variables and methods that are affected by the things you just marked. Do this as many times as you need to, to see how effects propagate from the change. When you do that, you’ll have a better sense of what you have to test.

One of the best techniques for learning about code is refactoring. Just get in there and start moving things around and making the code clearer. The only problem is, if you don’t have tests, this can be pretty hazardous business. How do you know that you aren’t breaking anything when you do all of this refactoring to understand the code? The fact is, you can work in a way in which you don’t need to care—and it’s pretty easy to do. Check out the code from your version-control system. Forget about writing tests. Extract methods, move variables, refactor it whatever way you want to get a better understanding of it—just don’t check it in again. Throw that code away. This is called Scratch refactoring.

The first time I mentioned this to someone I was working with, he thought it was wasteful, but we learned an incredible amount about the code that we were working on in that half hour of moving things around. After that, he was sold on the idea.

Scratch refactoring is great way of getting down to the essentials and really learning how a piece of code works, but there are a couple of risks. The first risk is that we make some gross mistake when we refactor that leads us to think that the system is doing something that it isn’t. When that happens, we have a false view of the system, and that can cause some anxiety later when we start to really refactor. The second risk is related. We could get so attached to the way that the code turns out that we start to think about it in those terms all the time. It doesn’t sound like that should be so bad, but it can be. There are many reasons why we might not end up with the same structure when we do get around to really refactoring. We might see a better way of structuring the code later. Our code could change between now and then, and we might have different insights. If we are too attached to the end point of a Scratch refactoring, we’ll miss out on those insights.

Scratch refactoring is a good way to convince yourself that you understand the most important things about the code, and that, in itself, can make the work go easier. You feel reasonably confident that there isn’t something scary behind every corner—or, if there is, you’ll at least have some notice before you get there.

If the code you are looking at is confusing and you can determine that some of it isn’t used, delete it. It isn’t doing anything for you except getting in your way.

Sometimes people feel that deleting code is wasteful. After all, someone spent time writing that code—maybe it can be used in the future. Well, that is what version-control systems are for. That code will be in earlier versions. You can always look for if you ever decide that you need it.