The Geometry of Dreams and

the Dimensions of Consciousness

It is never literally true that any form is meaningless and ‘says nothing’.

Every form in the world says something. But its message often fails to reach us,

and, even if it does, full understanding is often withheld from us.1

– Wassily Kandinsky

What does a sphere the size of a marble or hazelnut have in common with the origins of the universe? Perhaps as a child you played with marbles? Like me, you may have had one that you prized above the others. I favoured a large transparent marble with rainbow-coloured swirling strands entwined within it. I used to hold the treasured marble in my hand and roll it around, feeling soothed by its smooth cool surface. Sometimes, I would extend my hand, rest the marble on my open palm, hold it up to the light and wonder admiringly at the colours its form contained. The marble’s inaccessible beauty within spoke to me of different worlds. Imagining it now, I can feel its solidity in the centre of my hand.

Little did I know then that one day a physicist, describing the origins of the universe, known as the ‘Big Bang’, would take every child’s imagination to a new level by using a marble about one inch in diameter to show the size of the universe at 10-34 seconds!2 This theory purports that all the ‘stuff’ in the universe exploded out of ‘nothing’, albeit a particular kind of nothing, namely a quantum void filled with masses of subatomic particles that fluctuate into forms.3

In 1373, a time when Ptolemy’s flat-Earth perception yet prevailed in Europe, an English woman in her thirties had a series of 16 deathbed visions in the early-morning hours, in which she met Jesus. One of these visions prefigures the something-from-nothing cosmology of the Big Bang:

In this Revelation he showed me something else, a tiny thing, no bigger than a hazelnut, lying in the palm of the hand, and as round as a ball. I looked at it, puzzled, and thought, ‘What is this?’

Then the answer came: ‘It is everything that is made.’

I wondered how it could survive. It was so small that I expect it to shrivel up and disappear.

Then I was answered, ‘It exists now and always because God loves it.’ Thus, I understood that everything exists through the love of God.4

Inspired, this woman recovered and wrote down what she called her ‘shewings’. The book she wrote about her visions, Revelations of Divine Love, has become a classic of Christian mysticism. She became known as Mother Julian of Norwich and, inspired by her visions, she withdrew from the world into seclusion in order to contemplate the Divine, living in a small cell that was attached to a church in Norwich, England.5 Through the narrow window facing outwards, she gave spiritual guidance to all who sought it. Paradoxically, within the confines of her narrow cell, the more Julian turned inward, the greater her outreach in the wider world.

We might wonder how someone from the 14th century had a dream-like vision of a ‘little thing the quantity of a hazelnut’ that would contain the seed of a scientific theory yet to be conceived. Six hundred years later, the physicist Louis de Broglie postulated an analogy of structure between our minds and our physical world; otherwise, he argued, humanity could not have survived.6 De Broglie cites Albert Einstein’s visual way of thinking as an example of how the mind can reach conclusions that differ from the everyday sense of perception of space and time.7 According to Einstein’s biographer, Einstein credited his capacity to think visually and intuitively in his thought-experiments as leading to his Theory of Relativity.8

We see a similar principle at work in a dream that inspired the 19th-century chemist Friedrich August Kekulé to conceive of the structure of the benzene molecule. Kekulé, weary from his researches, had turned his chair towards the fireplace and dozed. He later recounted:

.... Again, the atoms were flitting before my eyes. Smaller groups now kept modestly in the background. My mind’s eye, sharpened by repeated visions of a similar sort, now distinguished larger structures of varying forms. Long rows frequently close together, all, in movement, winding and turning like serpents. And see! What was that? One of the serpents seized its own tail and the form whirled mockingly before my eyes. I came awake like a flash of lightning. This time also I spent the remainder of the night working out the consequences of the hypothesis.

He adds: ‘If we learn to dream, gentlemen, then we shall perhaps find truth ... We must take care, however, not to publish our dreams before submitting them to proof by the waking mind.’9

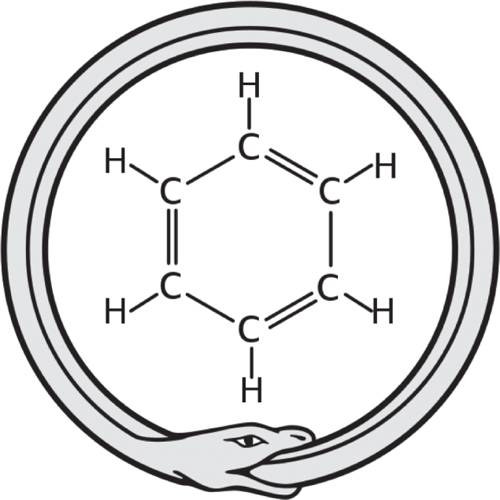

Kekulé serpent shares a lineage with the alchemical image of the ouroboros, a snake eternally eating its own tail – a symbol for life’s constant regeneration (see figure 7-1).

Figure 7-1: The Ouroboros and Carbon Ring

Jung pointed out that Kekulé’s practical application of his inner vision accomplished what the lengthy experiments of the alchemists had striven for in vain.10

Current research into dreams investigates the correspondences between our dream life and how our minds construct waking reality. Allan Hobson, psychiatrist and dream researcher, has argued that the REM dream state lays down the foundations of a ‘protoconsciousness’ upon which waking consciousness depends.11 According to this theory, during sleep, the brain optimises its conceptual model of the world by creating a virtual reality.12

The dreamscape is ‘fictive’ in the sense that it does not correspond exactly to waking life, yet it nonetheless reveals underlying principles of how form and movement evolve in the natural world. One basic principle at work in Nature is symmetry. The word symmetry, made up of the prefix sym, meaning ‘the same’, and the root metre or measure, gives us an insight into a key property of symmetry. Every time we look into a mirror, we see one of the most common forms of symmetry: ‘bilateral symmetry’. An object possessing bilateral symmetry, such as the human face and form, is composed of two ‘mirroring’ halves that form a whole. Butterflies, trees and flowers, for example, share this symmetrical property. In Nature, the arts, sciences and dreams, symmetrical proportions, like those inherent to the circle, convey qualities of beauty, harmony, balance and completeness. Dream researcher and physicist Nigel Hamilton has identified symmetrical development as part of a natural and organic process whereby, through the evolution of symmetrical forms in our dreams, ‘something is actually being constructed in the psyche’.13

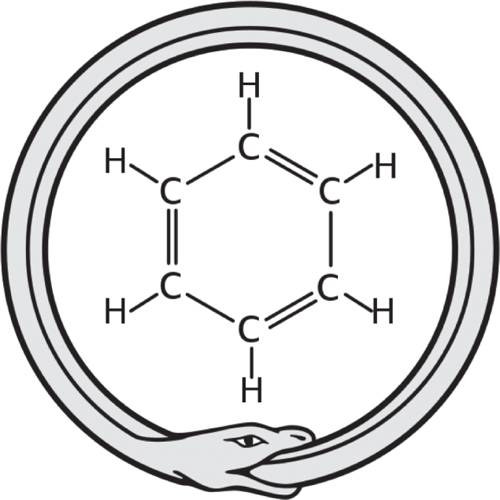

To give an illustrative example of this principle at work, we can visualise the symmetries that form part of a circle’s construction. A circle forms from an infinite series of two-dimensional polygons. as follows (see figure 7-2):

Figure 7-2: Creation of a Circle from Polygons

Starting with the three-sided equilateral triangle, adding a fourth edge to form a square, followed by a pentagon, hexagon and thereby to an infinite series, the straight edges of the polygons eventually round out to create a circle. In this way, a circular shape can be said to contain all the preceding polygons within it, much as the ‘ball’ held in Mother Julian’s hand contained all that exists.

Let us focus on two fundamental geometric forms, the circle and the square, in order to explore how the appearance and evolution of their symmetries can encourage and express a dreamer’s progress towards emotional balance.

First, consider the circle. Carl Jung, through his analysis of dreams, understood a circular or spherical shape to be a numinous archetype of the innermost self; forms such as a round stone, table, full moon or pearl all having the capacity to evoke an inner movement towards wholeness. Jung saw this archetype of the self as expressed in the universal symbol of the mandala, which, as he explains, ‘portrays the self as a concentric structure ... invariably felt as the representation of a central state or of a centre of personality essentially different from the ego’.14 In the 13th century, the mystic Meister Eckhart expressed a similar idea as ‘Being is God’s circle’.15

When we lose our sense of direction, a sense of what centres us in life, we can feel fragmented and lost rather than whole. At such times, the geometry of dreams can provide us with an internal compass, guiding us ‘home’ to our innermost self. For example, a circular shape appears in a dream that I had in my late twenties when teaching at a school in the Swiss Alps. I was feeling rather lonely and unsure about whether to continue teaching or to return to my homeland:

A circle of elders from the church where I grew up appear in an empty white room full of light. One of the dear ladies who had been my Sunday school teacher approaches me and asks what seems wrong. When I tell her of my worries, she takes out a piece of paper with a list on it. Glancing down at the list, she places her finger midway on it and says, ‘But Switzerland is on the list!’

I woke up grateful for the dream and affirmed in my choice to move to Switzerland and in my decision to stay a while longer.

We find a circular form elaborated in a visionary dream had by one of the great holy men of the Oglala Lakota tribe, Heȟáka Sápa, more widely known as Black Elk. As an adult, he recollected the vision he had at the age of nine when severely ill, in which, as he relates,

I understood more than I saw; for I was seeing in a sacred manner the shape of all things in the spirit, and the shape of all shapes they must live together like one being. And I saw that the sacred hoop of my people was like many hoops that made one circle, wide as daylight and starlight, and in the center grew one mighty flowering tree to shelter all the children of one another and one father. And I saw that it was holy.16

In Black Elk’s vision the ‘hoops’ overlap, creating increasingly complex symmetries. The multiple symmetries enhance the powerful unifying effect of his vision.

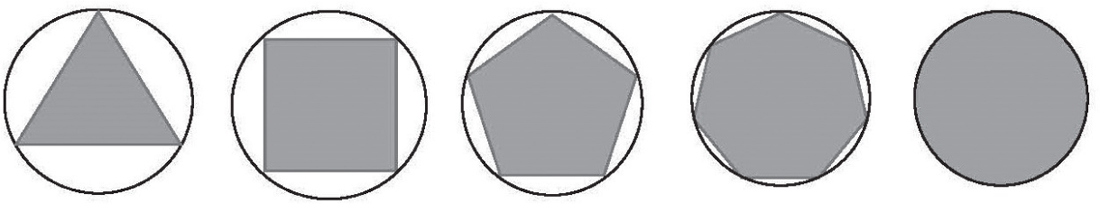

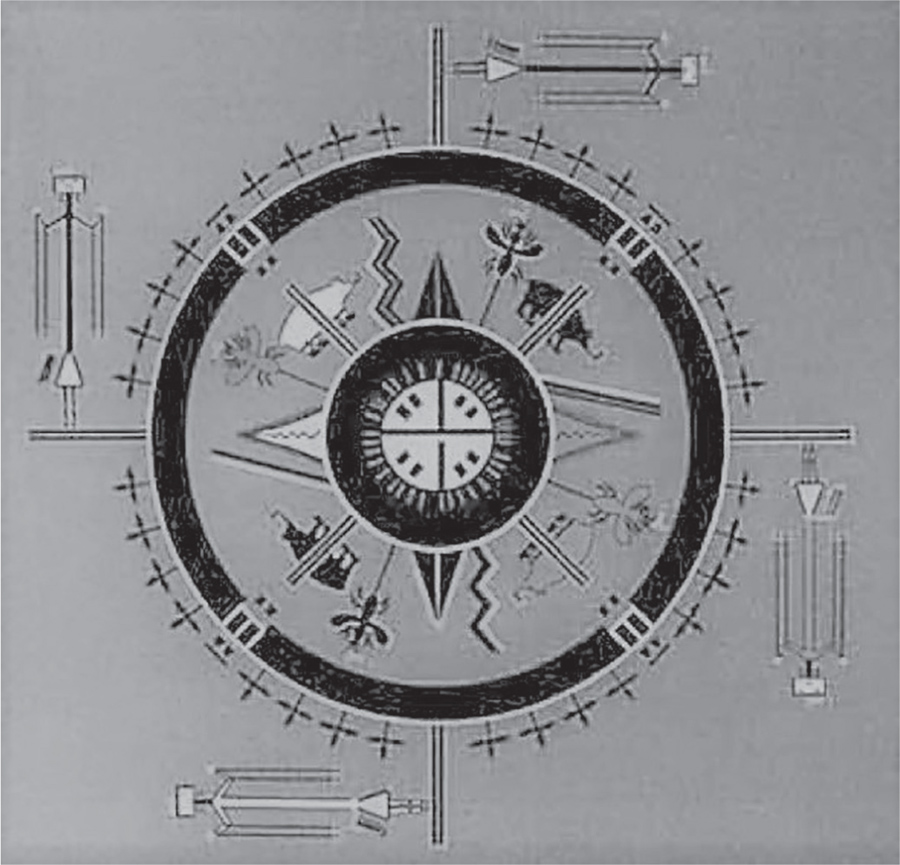

On the medicine wheel of Native American indigenous cultures, the circle is divided into four quadrants, giving the compass of the four directions: north, south, east and west (see figure 7-3).

Figure 7-3: The Four Directions

The quadrants also depict the cyclic movements of life on Earth, from day to night, season to season, year to year – the Wheel of Life. On a cosmic scale, this extends to the orbits of planets and galaxies and, beyond that, to the birth and death of universes.

A dream’s healing movement towards inner balance is embodied in the sandpainting ritual of the Navajo tradition. The medicine man creates a large medicine wheel of coloured sands on the ground. The mandala’s symmetrical imagery portrays the internal balance that the ill person needs in order to achieve physical and psychological wholeness, while the wheel’s centre symbolises a three-dimensional portal to the spirit world. The supplicant sits in the centre, facing east, so that the spirits can bring healing agents while taking away the causes of the illness and imbalance. Singing holy chants, the medicine man paints the sands from the mandala on the participant’s body as a ‘visual prayer’ (see figure 7-4).17

Figure 7-4: Navajo Sandpainting

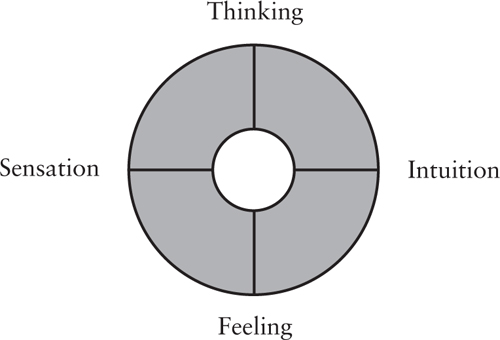

The rebalancing accomplished by the quadrants of the Navajo sand-painting ritual find a parallel in Jung’s four-functions model of the human psyche: thinking, feeling, intuition and sensation (see figure 7-5).18

Figure 7-5: The Four Functions

According to Jung, one function frequently tends to dominate in each of us while another remains undeveloped, the effect being to cause an imbalance in the psyche. For example, if we fail to employ our thinking function to help us make discerning, even-handed judgements, we may become too emotionally unstable and liable to act impulsively. Conversely, relying solely on our thinking function, we may become too driven and lose touch with our humanity. Similarly, someone who relies too heavily on sense perception risks neglecting their inner intuitive guidance, while intuition needs to be ‘grounded’ in everyday life.

A dream had by a man in his forties, Paul, mirrors an imbalance in his feeling function. Paul had lost his parents some years before. He felt his own sense of purpose had died with their deaths, and he had not regained it since. The theme is one I see often in therapeutic dreamwork:

A little boy is lost, and I am looking for him.

The child has no name.

When I asked Paul how he felt when he woke up from the dream, he replied adamantly that he did not know. But, after some time, he suddenly said, ‘I know how I felt when I woke up from the dream: lost!’ I responded by saying that if some-thing was lost, that meant it could be found. This dream marked the point from which Paul began to make a new start in life by re-engaging with the ‘lost child’ in himself. Paul’s dream experience reminds us that when we feel lost in life, it is important for us to acknowledge our own feeling of lostness before we can move forward.

As we work with our dreams, gaining better insights into ourselves and others, this new understanding may be expressed in the shift from two-dimensional to three-dimensional forms, such as from the circle to the sphere. In dreams, this development entails an increasing gravitas, a further centring of the personality that imparts a healing sense of wholeness and balance.

The inner expansion of consciousness is mirrored in the sphere’s flawless internal symmetry – no matter how we cut a sphere in two, both halves remain identical. Nicolaus Copernicus described the sphere as ‘most perfect’ and ‘best able to contain and circumscribe all else’.19 Lacking vertices or edges, the sphere provides the smallest surface area for any given volume.

Gravity produces spherical forms at different orders of magnitude, from water droplets to planets and stars. Nurtured by light, out of Earth’s spherical unity, myriad forms evolve – mineral, plant, animal and human. On a macroscale, some astrophysicists these days propound a sphere-shaped universe.20 What may lie beyond that sphere, we do not know!

The appearance of three-dimensional symmetrical forms in dreams indicates a growing capacity to face life’s challenges with equanimity, creativity and a more expansive consciousness. For instance, a woman named Rachel shared two dreams with me in which sphericity began to evolve. Prior to having met me, she had been working to free herself from a childhood blighted by harsh and punitive religious dogma, but she had yet to create what she beautifully described as her own ‘gospel of the soul’. In the first dream, Rachel watches a female artist who demonstrates a painting technique. She recounts:

I watch in awe as her brush moves with multiple speed over the canvas. Using her imagination, she is creating an image of nature but the brilliance of her stroke and brush techniques is enhanced by a further magical ingredient. So, what’s being produced by her is mingled with an independent force that is co-creating the image on the page. ‘This is God!’ she exclaims to me.

On waking, Rachel aligned the mysterious act of creation with what she called ‘the god-element’ in herself.

Over the ensuing two years, Rachel also underwent training with me in the psychotherapeutic application of dreams, during which she further developed what Jung would describe as her own ‘symbolic life’.21 Towards the end of her training, the theme of painting returned. In this second dream, both the painter and the shape of the painting surface take a different form from the earlier dream:

I’m painting, creating some artwork with rich colours, in a large shallow round bowl. My brush is whizzing at top speed, making spirals and circles that merge. Then I add some water to the bowl – I’m thinking the patterns will be washed away, but I’m on a sort of automatic pilot, so swish the water around. As I tip it out an amazingly beautiful, detailed and complete picture emerges. It’s colourful with reds and yellow and in three parts. The central panel depicts a biblical or alchemical figure who fills the space. On either side are two panels of faces and figures, some serene and holy and others tortured and stressed... There’s an implication that the characters are aspects of Self that I need to integrate to attain the central image. I am filled with a sense of magnitude of what’s magically produced itself to me.

Comparing these two dreams, Rachel observed that in the second she moves from watching the female artist to becoming the woman who creates – in other words, from observing a two-dimensional picture of the artist to participating in a three-dimensional embodiment of her own creativity. As Rachel herself explained: ‘In the first, God produces art; in the second, art produces God. It’s as if two parts of a whole have been joined.’

Importantly, the painting surfaces in the first and second dream differ. In the first dream, the artwork arises on a two-dimensional plane. In the second, it manifests in a three-di-mensional bowl. The appearance of the bowl parallels a sense of growing spaciousness in Rachel’s personality, a balancing of her feeling and intuitive functions in relationships to her previously dominant functions of thinking and sensation. The appearance of three panels indicates an opening to a spiritual dimension within Rachel’s psyche, three being a number traditionally associated with divinity. As Rachel senses, the two dreams fit together as part of an ongoing integration of her spirituality and creativity.

Similar to the evolution of the circle to a sphere, dreams can signal a movement from the square to the three-dimensional cube (see Figure 7-6).

Figure 7-6: Expanding Dimensions

Inwardly, this shift from two to three dimensions represents the realisation of a lived space in which the dreamer is developing the capacity to engage fully with life. Interestingly, the Zen tradition teaches that it is the empty space within a house that makes it habitable, just as the hollow of a cup makes it fillable.

To return to Paul’s ‘lost child’, as Paul continued with his inner work, he had a dream that reflected this same dimensional shift. He found himself standing in an unfamiliar, unfurnished room with three unknown people. He noticed two odd things about the room – there were no windows, and the floor was covered by a few inches of water. Although this dream initially frightened Paul, I could see it as holding promise: the four people (in total) suggested something being ‘squared’ or more fully structured and contained within Paul’s psyche. The as yet unfurnished room, a three-dimensional space, revealed potential for his self-development, while the water implied the healing emergence of life-giving feelings.

Paul said that the windowless room made him feel claustrophobic. ‘What,’ I wondered, ‘does “claustrophobic” mean to you?’ He sat up in his chair: ‘That’s exactly what the man in the dream asked me! It must be important!’ After that, he related the claustrophobic feeling of ‘having no choices’ to how he felt about his life. In this example, reflecting on his dream enabled Paul to ‘see’ how he was feeling and why. He could then explore whether or not it was absolutely true that he had no choices and how he might make choices more possible for himself, opening new windows on his life.

As we focus on the movement from the square to the cube, I will briefly share the significance of a sequence of four dreams from my own life over an 18-year period.

The first dream occurred when I was 27, two years after I had moved from the United States to Poland, where I set up an English department in a teacher-training college for foreign language teachers. At the time of this dream, I was in love!

My partner and I stand on the beach in California looking out at the sea. On the horizon, a large wave rises up, the black immensity of it increasing to skyscraper heights. The surface looks like obsidian, smooth and shiny. As the tidal wave approaches, it sucks up the water in front of it. Taking a hold of my partner’s hand, I say, ‘We can survive this if we run out to meet the wave and dive low under it.’ We run out into the water to meet the wave. Then I shout, ‘Dive!’ I am aware of the wave’s awesome power and pressure as it passes endlessly over us. Finally, we float up to the surface. The water floods the shore for miles. On the surface of the black seawater float photographs from our childhoods, in the old Kodak style – square with a white border. Strangely, a wooden pier sticks out of the water, and we swim for it.

In this dream, two-dimensional squares appear in the form of photographs from my childhood. But at the time of dream, my focus was externalised, so I was not aware of how the emotions of my past were shaping my life choices.

Between this dream and the next in this series, some 16 years passed. Over those years, although I had any number of life experiences, living, studying, writing and working in different countries, my conditioned responses and unconscious patterns had not changed much. Longing for real change in myself and my life, I undertook trainings in psychotherapy and yoga, gaining both theory and practice as I learned ways to work with the psyche and body, and entering a more introspective phase in my life. These new ways of thinking and being gave me deepening insight into myself and others. My dreams became increasingly lucid, with imagery indicative of a movement towards a more conscious understanding of my own conditioned worldview.

One night, I had a dream in which the imagery reminded me of the earlier dream of photographs floating on the sea, but with a difference:

... I notice a wall on which hundreds of key chains hang on hooks. Squares of glass, half an inch in thickness, dangle from each key chain. Small photographs from my childhood have been embedded in each. Fingering one of the key chains, I see that the glass gives a life-like dimensionality to the photo within, making it look as if I could step into the scene. The glass key chains reflect the light, bringing out the vitality in each image. I suddenly realise that I am looking upon key moments from my childhood and the early events that had shaped my life. I feel tenderness towards my child self. Then I awake.

The dream reflected my growing awareness of the conditioning of thought and behaviour that I had learned as I child, but rather than judging myself dismissively or critically, I could now look upon the child in me with understanding and compassion.

After completing the training in psychotherapy, I became the director of a charitable counselling centre – a very demanding job, particularly as the main funding source for the charity was soon to be withdrawn! The task ahead felt daunting, and only my belief in the value of the service outweighed my fears. I decided I would take each day one step at a time. Then I had this dream:

I am at the centre where I work, which has three counselling rooms in a row. Entering the middle room, I am surprised it opens into a kind of massive airplane hangar. There, many workers carry large shining black cylinders, each with gold writing on the top. They go about their tasks reverently and silently. I now see that cubic receptacles line the hangar’s left wall – at least 6 million, I think to myself! It strikes me as odd that white ash covers everything. I suddenly realise that these workers have a sacred task: they are sorting out all the ashes from the Jewish victims of the Holocaust and placing the ashes of each individual into a cylinder, the writing in gold leaf on the top recording the person’s name in Hebrew. The workers have nearly completed their work. I feel profoundly moved by the preciousness of every individual life lost, the weight of their suffering, and the terrible price that has been paid. I fall to my knees with the power of this awareness. Then I awake, deeply moved.

On a universal level, the dream addresses a collective awareness of what the tragedy of the Holocaust has meant for humanity. On a personal level, the three-dimensional cubical boxes both foretell and prepare me for the capacities that I will need for the work ahead. The many workers who appeared in the dream suggest to me that I will have help from many others in supporting the centre, which, thankfully, I did. The dream also heralded the transformative work of the counselling centre, where so many people would undertake the life-changing task of sifting through the ashes of their lives to reconstitute a new sense of self.

The final dream came at the end of a challenging first year as director of the charity:

I am walking with my mentor. He cups his hands saying, ‘This is how it can always be.’ I am swept into the interior of an immense cube composed of luminous blackness. The winds in that space carry me across the various diagonal, vertical and horizontal axes that meet at the cube’s mid-point. The winds refresh and invigorate me, and my consciousness feels light and full of spirit, like a child on a swing. Then I awake feeling refreshed.

In this lucid dream, the abstract shape of the cube becomes the primary structure. In the event, I went on to direct the centre for another seven years. Throughout my time there, I had a number of dreams such as this one, supporting me and giving me inspiration and strength.22

Our efforts to realise the truths our dreams hold can be likened to the endeavour to solve the problem posed by geometers of antiquity to square the circle. The challenge was to find a way to show how the surface area of a circle could be made equal to the surface area of a square. This mathematical conundrum has no perfect solution – the result is always an approximation, no matter how the size of circle and square are adjusted. There is, however, a symbolic solution for the alchemists’ attempts to square the circle which, although not mathematically precise, created what Jung viewed as a profound image of the inner self,23 one that can be illustrated as follows (see Figure 7-7):

Figure 7-7: The Squaring of the Circle

In a dream, the squaring of the circle may appear in imagery such as the full moon reflected in a square mirror.

By envisioning the squaring of the circle as a sphere contained within a cube, there comes a further enhanced sense of expanding possibilities, a widening and deepening of consciousness. This could be revealed by the presence of a round table within the four walls of a room.

When we understand the ways in which a dream’s internal geometry gives form to our state of being, we grasp more fully how each dream, like a sphere no bigger than a marble, or the hazelnut-sized ball remarked upon by Julian of Norwich, holds ‘everything that is made’.