AFTER THE PLEASURE OF spending the holidays at home in Red Cloud while being celebrated for the triumph of Death Comes for the Archbishop, 1928 started poorly for Cather. Her father, with whom she always had a tender relationship, died rather suddenly from heart problems. Her mother took temporary refuge in California with Cather’s second younger brother, Douglass, but while there suffered a debilitating stroke and had to be moved to a care facility. Nearing fifty-five, Cather was becoming part of the older generation. Her home at 5 Bank Street in New York had also been lost; she and Edith Lewis had moved into a hotel, the Grosvenor, intending only a brief stay there until more suitable arrangements could be found. But for the next five years Cather would have no permanent address aside from the Grosvenor, and most of her things stayed packed away in storage. She traveled constantly—to Nebraska, to California, to Canada, to France—to attend to family and professional matters. During this time of loss, however, she did have some solace. The cottage she shared with Lewis on Grand Manan Island was a refuge. More important, she continued to write. In 1928, while on their way to Grand Manan, she and Lewis stopped in Quebec City, and when Lewis fell ill Cather had unexpected time to wander around the old French settlement. What she saw stirred her, and she set to work on a new novel. Shadows on the Rock, concerned with the day-to-day life of a handful of citizens in 1697 Quebec, was published by Knopf in 1931 and became one of the top-selling books of the year.

February 10 [1928]

Red Cloud

Dear Alfred;

I have not written you, as I expected to be in New York at this date. My father has been very ill for the last two weeks, his second attack of angina, and that has kept me here. The things I want to discuss with you are hard to take up by letter.

The demand for the Archbishop seems a mixed blessing, as even now there seems to be no very adequate method of satisfying it. As I telegraphed you last night, the dealers here and in all the little towns about have been trying [to] get books from McClurg, Chicago, to fill the orders of a few patient friends who were not able to get the book for Christmas. Finally McClurg wrote the dealers here that they have ordered the books to be sent direct from the publisher to Grice & Grimes, Red Cloud. So far, they have not come. If all these little town dealers in Nebraska, Kansas, Colorado, Iowa, who always order from McClurg, can’t get books, isn’t there something wrong with the method of distribution? They tell me all their orders for “Antonia” are filled quickly and without trouble.

I have been here nearly three months, and in all that time the book has not had a fair chance in this little town, or in this part of the state. I don’t know about Omaha, but it has been impossible to get the book in Lincoln part of the time. I’ve had so many complaints from Catholics all over the country that I’m afraid there has been the same difficulty in getting books, East and West.

When you decided not to give the “Archbishop” any individual advertising, then I understood that it was up to the book to sell itself if it could. But how can it sell itself if it is not printed, and if the jobbers don’t carry it? It was out of print for a week or ten days at the most critical part of the selling season. Only ten days, but they were the ten days before Christmas. However, that’s over. The point I raise is, why is it still so hard to get books?

I shall start east in a week or ten days, as soon as I feel that it’s quite safe to leave my father. I’m your personal friend and admirer, now and always, but I don’t think you’ve given the Archbishop a flattering share of your interest and attention. With any personal enthusiasm behind it, I feel sure the book would have done much better. But we can talk of these things much better than we can write of them. I write a devilish hand at best and I’ve been under a considerable strain since father fell ill.

Faithfully

The Knopf offices, upon getting this letter, responded quickly with a promise to investigate. Internally, they suspected that Cather was exaggerating the problem.

![]()

In February, Cather returned to New York, since her father seemed to be recovering. On March 3, however, Charles F. Cather had a heart attack and died. She immediately took a train back to Nebraska, arriving very early in the morning the day after his death.

April 3 [1928]

Red Cloud

My Dearest Dorothy:

My father died on March 3d, just seven days after I had left home for New York. He was ill only a few hours—angina. He was happy and gay to the very end. I’d like to show you his picture sometime, he kept such an extraordinarily youthful color and young eyes and figure. He was very handsome, in a boyish Southern way. I have lost people I loved terribly, young people, but this is the first death there has ever been in our family—never a child or grandchild. I did not know death could be so beautiful. I got home to him a little after five, just as the dawn was breaking over him. He lay on a little stretcher in the big bay window of his own room, in one of his long silk shirts, and all the rest of the tired family were asleep. He looked so happy, so contented, so at home—his smooth fair face shaved—everything as it always was. He was such a sweet southern boy and he never hurt anybody’s feelings, not even in death.

Think of it, my dear, this winter of all winters, I had here with them, simply because I felt we could never be so happy again. I stayed because they were both so well, not because they were ailing. Having had those three months as by a miracle, I’ll stand a good deal of punishment at the hands of fate.

Dear, I never knew any Preston in Pittsburgh. I knew a Preston Cooke Farrar but no Preston.

Mother went to California with my bachelor brother two weeks ago. I’ve been staying on alone to have a lot of papering and repairing done. Such a nice wise, kind Bohemian paper-hanger to do everything. And just silence in the old house and in father’s room has done so much for me. I feel so rested and strong it is as if father himself had restored my soul.

I suppose after Easter I must go back to the world—but not for long.

Lovingly

Willa

![]()

Though Cather and her parents had been lifelong Baptists, they were confirmed as Episcopalian in 1922. Charles Cather’s memorial service was held in Red Cloud’s Grace Episcopal Church.

Monday after Easter [April 9, 1928]

Red Cloud

My Dearest Mother;

After two weeks of spring we had a bitter cold Easter. Elsie and I decorated the altar in memory of father. The church was nearly full of people. After the service I gave one of the Easter Lily plants to Molly [Ferris], and one to Hazel Powell, and the daffodils I took down to father’s grave—you know he loved the “Easter flowers” as we used to call them, and they are the very first flowers I can remember in Virginia.

I had dinner with Will [Auld] and Charles [Auld] at the hotel. Later I made a call on Mrs. [Alta] Turmore and Clifford—she had asked me to dinner, but I could not go. Then I went over to Molly’s and had a delicious little supper with her. It was lucky Elsie did not try to come down, as the weather turned so bitter.

Isn’t it funny for me to be getting a card from the Peggs? When that bashful blond boy in the butcher shop lost his wife and baby I went down to Carolina and ordered a lot of those beautiful snapdragons such as were sent to father. Everyone felt so sorry. She had a tumor inside her which grew along with the baby and strangled it. A proper examination and operation would have saved her. She had been carrying a dead baby for several days. Dr. [James W.] Stockman only called [Dr. E. A.] Creighton when she was dying. Poor Albert walks about like a dead man.

Lizzie [Huffmann] has been at the Macs [McNenys’] for a week now, but she still dashes in in the morning to make the kitchen fire for me, and I dine over there occasionally. Helen [McNeny] is home sick with grippe.

I’ve got such lovely silk curtains up in the big dining room. My little old bed is painted primrose color like the washstand,—I mean the wooden bed that was in the west room. And the table in [the] downstairs back hall, which proved to be not walnut at all, I had mended and painted and it’s very pretty.

Molly had dinner with me here on Good Friday and Saturday nights, and says I’m a good cook. She helped me wash the dishes.

I had all father’s oak furniture gone over with furniture polish for you and it looks so much better. If ever you want it painted I’ll have it done.

Please write to me, dear mother.

With much love,

Willie

April 11 [1928]

Dear Roscoe;

Yes, indeed, I’ve been staying on in the old house and finding it such a comfort. I’ve had all the downstairs re-papered, except the parlor—thought mother might like one room just the same. They had to scrape off four layers of paper so it was a mess for days. Then I had father’s room papered in a lovely gray English chintz paper for mother. I’ve had the yard cleaned and new shrubs set out, and lovely drapery curtains put up in the front dining room. The back dining room really looks lovely. Ondrals, the nice old Bohemian painter will do the bath room over after I go. We had to do a good deal of plastering, as most of the sitting room ceiling fell down. These messy repairs could never have been made with mother here—it would have fretted her to death. I’m awfully pleased with the results, and I’ve seldom spent money that I’ve enjoyed so much.

Your draft I’ve registered in the one account book I carry about with me—a complete list of checks received,—and I’ll credit it on your note when I reach New York. I’ll stay on here a few days, then go to the Mayo’s for awhile, and on to New York. Edith’s poor mother is still dying—it is surely a long, hard way.

My love to you, dear brother and to all the ladies of your house. They are all grown up now!

Yours,

Willie

Sunday [April 1928?]

The Kahler Hotel, Rochester, Minnesota

My Dearest Mother;

I got here this morning, and will register at the clinic in the morning. This hotel has been made over and is now better than the Zumbro.

I spent about four hours with Elsie in Lincoln, and we had a long talk about you and your future. We are agreed that whenever you want to go home one of us will be there with you and we will do everything we can to make you happy there. We will put our whole heart into it. Elsie can get a year’s leave of absence next winter, she says. If she can’t, I will be there, I promise you.

I bought a sprinkler for the lawn at last, and before I left Mac [Bernard McNeny] and I were rivals in getting the grass green. The new shrubs Will and Amos set out are coming on well. I am paying Amos five dollars a month regularly to water and cut the lawn, and May 1st he and Floyd Turner [?] will set out big red zenias in the bare patch where father used to have various little flowers. I chose zenias because they are so hardy and will make their way alone.

There will be nothing desolate inside or outside the house if you want to come back to it, and everyone wants you to come. Elsie’s school is out the first day of June, so if you want to come back with Will Auld the first of June, Elsie can meet you there. The last word Lizzie said to me was, “Oh just let me know a few days before your mother comes, and I’ll make the house look like a palace for her.” You have your own house—the Bishop [George Allen Beecher] and Mrs. [Florence George] Beecher think it a very attractive one, and I’ll make it more and more so. And you have your own friends, and they miss you terribly and you will enjoy them more than you ever did before. Indeed, I love them so much for their loyalty to you that I feel I can never keep away from Red Cloud long again. That’s true!

So don’t be blue, Mother. You seem to me almost the most fortunate old person I know. You have Doug to travel with, and several of us to hang about you when you want to be at home. Of course if Elsie is with you next winter you will keep Lizzie, and I think we ought to pay Elsie, too.

Now cheer up; you are getting older, and that’s hard luck—but your children and all our old, faithful friends, and the young friends, too, are determined to make you happy.

With a heart very full of love for you

Willie

![]()

Characteristically, she fended off attempted inroads on her time, including a suggestion by Ferris Greenslet in late April that she write a biography of the poet Amy Lowell.

May 9, 1928

Grosvenor Hotel, New York City

My dear Mrs. Austin:

I wish the suggestion made by Mr. Greenslet and Dr. [Henry Goddard] Leach had come a year ago, when I had a good deal more time and energy than I have now. Just because I never write biographical or critical studies, editors bother me to death trying to make me do them. They simply want them because I resist their persuasions. Greenslet has just been trying to crowd on me a biography of Amy Lowell—I would be as likely to undertake a history of the Chinese Empire! I wouldn’t do it for the whole amount of the Lowell Estate,—simply because that sort of writing is an agony to me. I need very little money, and my life and liberty are very precious to me.

One of the pleasures of having an absolute rule is that once or twice in a lifetime one may break it, and if things were at all well with me, I would be tempted to break it on your account! [B]ut this has been a very bad winter for me, and I’m not going to do any writing at all for at least six months. My father died in March, and I have just come back to New York after several weeks at the Mayo Clinic. This is the first time in my life that I have ever felt absolutely tired, through and through, and I am simply going to rest for a while. I don’t know where yet, but I may go on to my mother, who is in California with my brother. For this year, my family concerns, father’s death and mother’s consequent breakdown have simply wiped out everything else. I know you will understand that I speak to you with a frank and open heart. Sometimes the difficulties of life are just too much for one, and then it is best to keep away from the desk.

Faithfully yours,

Willa Cather

![]()

In early June, after weeks battling influenza, Cather received an honorary degree at Columbia University.

TO MARY VIRGINIA BOAK CATHER

June 7 [1928]

New York City

My Darling Mother;

No, no, no, I’m not cross! But I’m still very wobbly from that influenza, and people have been unusually merciless in pursuit of me. I am not accepting any invitations, but even writing notes of polite refusal becomes a heavy task.

The Commencement at Columbia was really quite thrilling and splendid; I wish some of you could have seen it. I was the only woman among the seven recipients of honorary degrees, the rest were all old men, as you will see by their pictures. I sat between the French Ambassador [Paul Claudel] and the President of the University of California [William Wallace Campbell]. We were all in caps and gowns, of course. I really got a great deal more applause than any one else; Edith was there and she says the roar for me lasted twice as long. I rose when my name was called, walked up to the President [Nicholas Murray Butler] and stood there until the applause was over; then he made a speech at me and gave me a diploma, two Deans of the University put a gorgeous collar about my neck and fastened it on my shoulders, and conducted me back to my seat on the platform. The other six were applauded only after the degree was bestowed, but I was applauded like a ball game, both before and after.

The great old Cuban patriot, [Antonio Sánchez] du Bustamante [y Sirvén], seemed to be second in popularity, and he is a wonder. I was never so patted and embraced by so many old men at once.

After the exercise I went straight to the President’s supper party, not a dinner, as no one had time to put on evening clothes. I had to meet and talk to all the Trustees and their wives, and the Professors and their wives, and a lot of Cubans and Spaniards and attachées of the French embassy and their wives. They are many of them wonderful people, and it’s all very delightful, and exciting,–––and exhausting. I was a tired creature when I came home in President Butler’s car. If I’d realized it would be such [a] spectacular affair, I’d have sent for Mary Virginia to come down.

I am sending the silk-and-velvet collar of Columbia and the one I got at Michigan, home to Carrie Sherwood to keep for me. They are very large, I’ve no room for them now, and she has made a special place in her spare room to keep such things for me. You can see them, if you wish, when you go home.

I hope and pray you will like your beads, and do not say they are too young, for they are not. Everybody trusts my taste but my family!

In a few days I will send you some envelopes addressed to Grand Manan, where I think we shall go from here. All mail sent to this hotel will be forwarded, however.

With a heart-ful of love to you.

Willie

TO COLONEL BUTLER

June 14, 1928

New York City

My dear Colonel Butler:

I have to admit that I am a woman, and I must also admit that I can make no reasonable explanation of my name. I was born in Virginia, however, and in those southern states it used to be, and still is, very common for a girl to be given the first name of one of her male relatives; sometimes the parents tried feebly to give the name a feminine ending, as in my own case. If I had to be William, I would have preferred to be William without modification. This is a rather long explanation, but you seemed really curious on this point.

Thank you for your appreciative words about the book. It follows very closely the real story of the first Archbishop of Santa Fé and his vicar, and the scene, of course, is laid in a country that I know very well.

Very cordially yours,

Willa Cather

October 13, 1928

Grosvenor Hotel, New York City

Dear Prof. Goodman:

One of my friends who did hear your radio talk tells me that she liked it very much, but that she was a good deal distressed at hearing my name mispronounced throughout. My name should be pronounced so as to exactly rhyme with “gather” and “rather”. I think the name “Kayther” about the ugliest on earth, and I do consider it a hardship that people so often attach it to me. My friend Mr. Mather’s name is always pronounced correctly. Nobody ever thinks of calling him Mayther.

I hope you will pardon my calling your attention to this, but next to being called dishonest, I think I would rather be called anything than Kayther!

Very cordially yours,

Willa Cather

![]()

It was in June, on their way to Grand Manan, that Cather and Lewis first visited Quebec City. Lewis writes in her memoir that when Cather saw the city, she was struck by “the sense of its extraordinarily French character, isolated and kept intact through hundreds of years, as if by a miracle, on this great un-French continent.” In November, Cather went back to Quebec, this time alone. She was at work on Shadows on the Rock. During this same period she also wrote “Double Birthday,” a short story set in Pittsburgh. Fritz Westermann, mentioned below, was a friend from Cather’s university days and a nephew of Julius Tyndale.

Tuesday [November or December 1928]

Dear Elsie:

Just back from Quebec. I long-distanced M.V. [Mary Virginia] last night to find when her father would be here, and invited the Auld family to dine with me Sunday night.

I enclose letter from Fritz Westermann. You see I took no chances this time! The story “Double-Birthday” has a sketch of Dr. Tyndale in it, so I simply sent it to Fritz and asked him whether I should publish it or not—told him I wouldn’t think of doing it if it would annoy him or the Doctor.

It will be out in the February Forum [then written out more clearly:] (Forum). Dr. Leach says it is the best short story he ever published, but it’s really not much. I can’t work without a house to work in, and I can’t work where I hate my surroundings. I’ve always felt in my bones that Long Beach [California] would be just as you say it is. One has only to reason it out from the people who go there!

With love to you

W.

I think Fritz is real nice and un-grudging, don’t you?

Dr. Tyndale wrote Cather a note saying he was flattered to find any of his characteristics in one of her stories.

December 5, 1928

Grosvenor Hotel, New York City

My dear Mr. Barr:

I get, of course, a great many invitations to lecture, but very few of them are as tempting as the one you wrote some weeks ago when I was in Quebec. All my letters were held for me here, as I went away to escape from interruptions. My answer, therefore, is very tardy, and I apologize.

I always feel very deeply that I am a Virginian. My mother and father, though they went West long ago, were always Winchester people—not Nebraskans. Nothing would give me more pleasure than to talk for an hour or so to your students, and I hope that at some future time you will renew this invitation when I can accept it. This winter I can not make any engagements of that nature. The last year has been very much broken up, and I have got behind in my work and my life. My father died last spring, and since then my mother’s health has been uncertain. She is now in California with my brother, but I may have to go to her at any time. I always find lecturing tiring, and indulge in it but seldom. At some more fortunate time, however, I assure you I would like to go to Charlottesville and spend an hour with your young men [at the University of Virginia].

Very cordially yours,

Willa Cather

![]()

Early in 1929, Cather broke away from her work on Shadows on the Rock to go to her mother in California.

TO GEORGE AND HARRIET FOX WHICHER

New Year’s Day [January 1, 1929]

New York City

Dear Friends:

I meant to go up to the Lord Jeffrey to work for a few weeks soon after the Holidays. But now my mother has had a stroke in California, where she is staying with my bachelor brother [Douglass]. I shall have to go out there now in a few weeks and give up working altogether for the present. I’d made a pleasant start and hate to leave it. If only mother were in San Francisco! But Long Beach, near Los Angeles, is the most hideous and vulgar place in the whole world. Well, this last year was a bad one, and this doesn’t promise much better. But only a part of last year was bad—all the winter in Red Cloud, where your fruit cake found me, was lovely, lovely,—like a winter flower garden, opening more and more–––It was the sort of thing one has to pay for, and pay dear. I suppose I mustn’t squirm now.

Virginia and Tom [Auld] gave me good word of you all at Thanksgiving time, and I send you all the good wishes in the world for 1929. I got a shopful of handkerchiefs last week, and have given them all away but yours and two others—the only one’s I liked. I’m fussy about handkerchiefs.

With love to you all.

Willa Cather

[Probably April or May 1929]

Long Beach, California

My Dear Dorothy:

About Christmas time mother had a stroke here where she was spending the winter with my bachelor brother. At that time I was ill with bronchitis in the Grosvenor hotel, New York and could not come. I got away in February and have been here ever since, first hunting a little home with a porch and yard to move mother to, then moving her, then spending days and days shopping for hardware, linen, furniture, dishes, mattresses—everything a home requires. Mother is completely paralyzed on the right side, and speechless. Yet behind the wrenched machinery her mind and strong will, her whole personality is just the same. She can moan[?] some times—oh so seldom!—we can understand. My sister Elsie has been here from the first. We have excellent nurses, thank God, but a tall, strong woman paralyzed is the most helpless thing in the world. She has to be fed with a spoon like a baby. Constant changes of position give her the only ease she can have. My brother carries her from bed to bed to rest her, and takes her out on the porch in a wheel chair for a couple of hours. Your letter came while I was rubbing her yesterday. I read part of it to her and she remembered you perfectly, and the time she met you at the door. She made me understand that she had seen you much oftener than that once.

This is the most horrible, unreal place in the world, on a dreary curve of the coast, I have rheumatism dreadfully here, and never felt so down-and-out anywhere. My mail is a horror—all the greedy, grasping, intrusive people who want things from writers have never been so merciless. I live at a hotel and taxi-cab out to see mother in the afternoon at the above address. The mornings I spend shopping—the thing that was always the hardest of all things for me to do. Elsie stays at the house to regulate the nurses and the servant.

Oh if only this dreadful thing had happened at home, in a human land, where mother would have had her lovely grandchildren to watch and work[?], where there were dear old friends, kind neighbors, memories, God. There is no God in California, no real life. Hollywood is the flower of all the flowers, the complete expression of it.

I stayed at home two months last spring, after mother came to California, having the old home made more comfortable for her—worked awfully hard, took as much out of me as a book—now she will never see it. Well, there is nothing to write, nothing to say or do, my dear, except to stand until one breaks, and the quicker that happens the better, if only one can break clear in two, and not just half-way. This is why I’ve not written, because I’ve lost my bearings and can’t write except as bitterly and desperately as I feel. Father’s death was swift and gay—he was laughing two hours before he died. Goodbye, God bless you, and don’t remember this letter after you read it. There are enough people crushed under this poor sick woman who defied time so long. Goodbye, dear—nothing to say.

Willa

![]()

By late May, the family had moved Virginia Cather to Las Encinas Sanitarium in Pasadena, California.

[June 1929]

Dear Brother;

I am on my way East—will be at the Grosvenor Hotel 35 Fifth Ave. for the next ten days, then go to New Haven, at Hotel Taft. On June 19 I receive a doctorate degree from Yale—the second they have ever given a woman writer. The first was given to Mrs. Wharton eight years ago. She came over from Paris and stayed in New York one week to take it.

I hope you can skip out to see mother for a week this summer, and soon. Better come alone—its bad for her to have several about, she tries even in her feeble state to arrange, direct. I went North when Will Auld was here. Better come now than to her funeral—she will know you now and her mind is still unclouded, though often tired. She is losing ground a little all the time: now up, now down, but on the whole a good deal weaker and lower than when I first came three months ago. She tries, poor dear, but the odds are so terribly against her that I hope it won’t be very long, for her sake. Will Auld felt the same way. She is still herself, and can understand what you say to her. The trip would not be a very long one for you if you came by train. I had a round-trip ticket over this road, or I would have gone back by way of Rawlins. The Sanitarium is a really beautiful place—you could have quiet hours there alone with mother, the nurse in the other room within call. She may live like this a long while—several years, but is almost sure to deteriorate mentally and be less herself. It’s a cruel and pitiful thing, but you’ll be glad to have seen her, as I am. I’m wondering whether I will ever feel much enthusiasm for things again, though. I guess I will—for young people,—and young Art.

I had lovely visits with Jim Yeiser and Marguerite [Richardson] in San Francisco.

Willa

![]()

In the fall of 1929, Knopf was preparing to release a special edition of Death Comes for the Archbishop with illustrations by Harold Von Schmidt. Though Cather at first balked at the idea of an illustrated version, she was so pleased with the results that she later asked Knopf if they could print the illustrated version exclusively.

On the outside of the following letter was written:

Dear Miss [Manley] Aaron:

Please get all this to Mr. Stimson, as I have telegraphed him about it.

W.S.C.

TO GEORGE L. STIMSON, ALFRED A. KNOPF, INC.

October 17, 1929

Dear Mr. Stimson;

You are a violinist, put the mute on the biography—no the extinguisher! Anything more deadly dull than this jacket text, I can’t imagine. It’s all too foolish, and I really don’t think it’s up to the office to hand out these dull facts. They tell absolutely nothing about the book, or about me, nothing that the public wants to know.

Now, I want you to let me decide on this jacket text. Tell the public something they do want [to] know, something they write me letters about until my hand is fairly crippled with answering them; tell them something about how and why the book was written! That is what they want to know. Instead of this wooden stuff about my grandfathers and Von Schmidt’s (who in thunder cares about our grandfathers?) use this condensation I enclose of my letter to the Commonweal about the book. The English publisher had that letter printed in pamphlet form and gave it wide circulation—wrote me it was singularly effective as advertising. I have cut the article to just about the number of words in the two dreary sketches of Von Schmidt and me now on the jacket.

Please telegraph me that you will use the copy I’m sending you, and not that which is now in the proof of the jacket; and please write me the name of the person who wrote the copy, as I want to talk with her—or him—when I get back to town.

Now as to the copy I send you—very ragged, but I’m lucky to have even that with me.

1. Use quotes before every paragraph

2. When the long cuts occur, please end the paragraphs with asterisks.

3. Please read the proofs yourself and telephone me if you’re in doubt about anything.

Hastily, to catch the mail,

Yours

Willa Cather

Please note the change in the newspaper comment quoted. I beg you to use this one from the New Republic instead of that from the Baltimore Sun.

TO BLANCHE KNOPF

October 17 [1929]

My Dear Blanche;

Unless there is some very important reason why you must see me before you sail, I would like to stay up here about three weeks longer. This poor book has been jumped about so much—all it needs is sitting still. It’s going along smoothly now, and I don’t want to interrupt it just at this point. The working conditions are good, the country lovely, I am out of doors a great deal and feel awfully well—sprint up the mountain with a crowd of boys and don’t get used up. When I go back to New York I shall probably have bronchitis at once! Besides I can’t get my old quiet room at the Grosvenor for several weeks. So I really think I better stay on here for the present. When you come back I hope to be pretty well on my way with this book. It’s no world-beater, but I want it to be good of its kind—very quaint and dry, as I told you; mostly Quebec weather and Quebec legends. But of course the subject matter is a secret between us.

I hope you will have a splendid trip, and that you’ll see the Hambourgs. They’ve both been ill, and I’m very much worried about Isabelle, and I’d like to hear from you how she seems.

Of course as soon as I do get to New York I’ll report at the office.

With love and good wishes for a good journey

Yours

Willa Cather

Please send me Zona Gale’s new book [Borgia], and a book on Greek Domestic Life, or Greek Family Life in the time of the early church, that you published long ago. I remember an excellent sketch of the Empress Theodora in it, but have forgotten the title [probably The Byzantine Achievement, by Robert Byron].

W. S. C.

![]()

Yale French professor Albert G. Feuillerat apparently wrote Cather with questions as part of his work on an article about her books. On May 16, 1930, he published “Romancières américaines: Miss Willa Cather” in Figaro.

TO ALBERT G. FEUILLERAT

November 6, 1929

My dear Mr. Feuillerat:

I am sending you a pamphlet which my publisher sends to colleges and clubs that write to him for information about my books. At the back of this pamphlet there is a list of books which give such information, and I have marked the two which I think might be most helpful to you. The book “Spokesmen” by Professor [T. K.] Whipple, contains the latest and most comprehensive study of my books. The biographical sketch at the beginning of this pamphlet will answer one of your questions at least.

Your inquiry regarding a possible French influence is hard to answer. I began to read French when I was fifteen or sixteen, and for a great many years enjoyed the French prose writers from Victor Hugo down to [Guy de] Maupassant much more than I did English writers of the same periods. I never cared so much for French poetry as for English poetry; but almost any French prose seemed to me a little better than English prose, quite apart from the quality of the writer. Before I was twenty I had read all of the novels of Balzac a good many times. Now I do not read him very often. I don’t think I ever longed to “imitate” one French writer more than another, but in all the great French writers I have felt a greater freedom than in English writers of the same period; they experimented more often and had a wider range of variety—usually seemed a little more direct and sincere. About nearly all the fine old English novelists (before Thomas Hardy) there is a curiously professional tone toward the reader, a joviality a good deal like that of the landlord welcoming guests at an inn. When I was much younger this tone irritated me, I remember. I do not mind it so much now; it seems a manner like other manners, but perhaps the absence of this conventional geniality in French novelists pleased me, beside their range of interest was so much wider—their theme was not always the same story of how some one got settled in life.

I have written a long letter and yet I have told you very little of what I mean. I think I must always have cared for something nervous and direct and supple in French prose itself, when I was too young to think about it or reason about it. It excited me more than English prose, just as the air in high altitudes always makes me feel better and stronger than the air at sea level.

I may say that of all the French writers I have cared so much for at one time and another, I think I now enjoy Prosper Merimée perhaps more than any of the others. I feel as if the qualities which give me so much pleasure in other French prose are particularly present in him. I believe he is not fashionable in France at present, but he has almost everything I like in a writer—along with a proud reserve that makes me respect him.

Very sincerely yours,

Willa Cather

P.S. I think an essay I once wrote, called “The Novel Démeublé” will give you exactly the information you want. You will find a convenient edition of it listed on the last page of the pamphlet I am enclosing with this letter.

Sincerely

Willa Cather

![]()

Cather had reached the point in her career where honors began to pile up. In addition to the growing number of honorary degrees, she was notified in November 1929 of her election to the National Institute of Arts and Letters.

November 25, 1929

My dear Miss Gale:

As I feared, I won’t be able to accept the invitation from you [to come to Gale’s home town of Portage, Wisconsin] which pleased and tempted me so much. I shall have to go to my mother in Pasadena just as soon as possible after Christmas—which means that work is pretty much out of the question for this winter. But it is a lovely thing for me to remember that you did want to have me there, and I am not going to give up hoping for a sojourn near you at some future time. Things have been hitting me pretty hard of late, you know. You remember when Kent is in the stocks waiting for Lear, and says “Fortune turn thy wheel.”

On the long, slow train ride down from New Hampshire I read your new book [Borgia] with such delight and amusement—amusement that was rather grim. Of course we are all Borgias—especially when we really get interested in other people and have kind intentions. I nearly ruined the life of a young brother by bringing him off the farm and giving him what I thought were “advantages”. But one cannot live isolated in a test tube—and most contacts are pernicious.

If you come to New York before Christmas, or soon afterward, please let me know. I want very much to tell you about something that I wished to speak of when I saw you last fall, and didn’t. And I want to hear how things have turned out for the nice daughter you had with you—I did like that girl so much.

Always faithfully yours,

Willa Cather

![]()

Warner Brothers had produced a silent film of A Lost Lady in 1924, starring Irene Rich and George Fawcett, and now, with the emergence of sound films, sought to remake the movie. Talking actors introduced new considerations for Cather.

TO MANLEY AARON, ALFRED A. KNOPF, INC.

November 29, 1929

My dear Miss Aaron:

My hesitation about letting Warner Brothers have the sound rights of “A Lost Lady” has been due partly to the fact that they offered me a very low price and partly to the fact that I do not want my name attached to dialogue written by some person whose name and ability I do not know.

Of course, if they would agree to make no further use of my name than to say at the beginning of the film “Adapted from the novel of that name by Willa Cather,” I believe I would feel no further hesitation in the matter and would let them have it at the price they offer. I would however want a signed statement from them that they would, in all the advertising, use that phrase—“Adapted from the novel of that name by Willa Cather” or “Adapted from Willa Cather’s novel.” In case they are not willing to confine themselves to this limited use of my name, I would certainly want to have something to say about the person who should write the dialogue for a sound picture. I am writing you this letter because I have just heard that an old friend of mine, Zoë Akins, who writes for the movies is still in Hollywood. She is under contract at the Fox studio, I think; but the Warners might be able to make some arrangement to get her for the job, if they wished to take the trouble. Zoe Akins knows the period in which my story is laid, the part of the country in which it occurs and the kind of people who appear in it. Moreover, I feel pretty sure that she would do the best she could for me. You might send Warner Brothers a copy of this letter or extracts from it, and they could give you an answer. What they do not seem to realize is that I am absolutely unwilling to have the dialogue of the sound production written by some one I don’t know, and then have my own name used in connection with it.

Very sincerely yours,

Willa Cather

December 20 [1929]

Grosvenor Hotel, New York City

Dear Dorothy:

I feel as if I must manage to reach you at Christmas time, though I’ve no idea where you are. Forgive this dreary letter-paper—could anything be a better index of the dreary way in which I now live? I can’t take an apartment, you see, when I have to make two trips a year to California. I’m going there again in January.

Dear Dorothy, I can’t thank you enough for the letter you wrote me from Spain this summer. I still have it by me. It reached me in my little house at Grand Manan, an island about thirty-five miles out from the New Brunswick shore. I went up there immediately after the Yale Commencement and stayed until late in September—really got rested and began to like life again. Then I went to a place I often stay in New Hampshire and came back to town in November, because I had to see my dentist, oculist, lawyer, etc. One does have to come back to cities for some things, and it’s easiest where one has connections all ready made (I mean all ready, not already.) But as soon as I get back here, I get rather used up. The old New York of ten years ago wouldn’t tire me, but the present New York—words fail me!

Yes, that actress in Pittsburgh was Lizzie Hudson Collier, cousin of Willie Collier. I wonder where she is now? She was as kind and good as new milk, or fresh bread. The worst of living fast and hard is that one can’t keep in touch with all the people one cared for. But the first little circle, I’ve always kept close to them. I yesterday sent off eight Christmas boxes, (very carefully chosen and bought, the contents) to as many old women on farms within 25 miles of Red Cloud. There used to be fourteen of them (not so old, then) Swedish, Danish, German, Bohemian, Irish. In all these years, since the early Pittsburgh days, I’ve never been too poor or too busy or too sick to send them something at Christmas time. I’ve had some true lovers among them.—You see, I’d loved them first. “In her last illness she talked of you so often,” the daughters write me afterward. I live only to get back to those old friends again—as I have kept going back, winter and summer, whenever I could, for half a life-time. But you see I can’t go now, with mother so ill. She’s terribly jealous—it will hurt her if I even stop there.

Mother’s condition changes little—has improved a trifle, they tell me. Please give my love to your mother if you are with her. If you and I have to become the older generation, why in mercy’s name can’t it be done without so much pain? It’s like dying twice.

Well, I honestly set out to write you a cheerful letter—things are not so bad with me; I’m quite well, for instance. Instead of a chatty letter, it’s turned out a homesick wail. I suppose my heart is always out there at Christmas time (it is so bleak, you know; and if one can love the bleak and bare at all—why one loves it more than other things. If I take up a pen at all, I’m very apt to write what I’m thinking hardest about, so you get this queer letter, my poor Dorothy!

However, I do wish you a Merry Christmas, and a Happy New Year, God knows! If you are in town before the end of January, won’t you please let me know at this hotel?

Lovingly

Willa

December 31 [1929]

My Dearest Zoë;

Your wonderful crucifix has made me so homesick for the Southwest! What a touching and powerful thing it is—just the color of the poor believers in their little tawny houses. It’s a precious thing to have in New York. Thank you, with all my heart. I’ll be in California in February. Tonight I am leaving for Quebec to spend the New Year week. It will be lovely up there now—Miss Lewis goes with me and we’re taking a trunk full of coats and sweaters. There are mountains of snow over all this country now. I’ll drink your health in very good champagne tomorrow night, dear Zoë.

With love

Willa

[January 1930]

Hotel Grosvenor, New York City

Dear Mr. Greenslet:

Will you please ask your business office to send me a statement of all royalties paid me in 1929. I must leave for Pasadena in a few weeks and must make my income tax report early.

Hastily

Willa Cather

TO FERRIS GREENSLET

February 6, 1930

Hotel Grosvenor, New York City

Dear Mr. Greenslet:

You have emptied a pretty kettle of fish upon my head! Wasn’t it faithless of you (and, incidently, most illegal) to use my name, without my permission, in your ad. for Laughing Boy? Two old and intimate friends of mine published new books this fall, and their respective publishers asked me to let them use my name in exactly the way you used it. I refused in both cases, because if one begins that sort of thing there is simply no end to it. Sometimes the best possible friends write the worst possible books, and if they come to you and say, “you allowed your name to be used for this book or that book,” what is one going to say in reply? The only way to keep out of embarrassing situations is consistently, and in every case, to keep one’s name out of blurbs and advertisements. It’s quite right that reviewers and people who write professionally about books should be quoted, that is their job and their judgment ought to count for something, but a friendly expression of interest in a book surely ought not to be used in print without one’s consent.

Now that I have got this off my chest, please have someone send me a copy of the new edition of Antonia. Living thus in a hotel, I have none of my own books, and I want to make some corrections in Antonia for the English edition (and for you, if you will make the corrections.)

Also, since I am leaving for California about the 20th, would it be convenient for you to send me my royalty check sometime next week instead of March 1st? I want to get my business affairs all straightened up before I go, if possible.

Very sincerely yours,

Willa Cather

March 10 [1930]

Las Encinas Sanitarium, Pasadena, California

My Dear Dorothy;

Mother had a little chuckle over the Mark Twain dinner picture you sent me. She is a little stronger than last spring but just as helpless,—and her state is just as hopeless.

Sometimes I wonder why they build up a little more strength for people to suffer with. My sister is off for a few days rest and I am kept pretty busy trying to divert mother a little. We have a charming English nurse who has been with her a year now and never fails us. I have a nice little cottage of my own near mother’s cottage, the food here is excellent and I am very comfortable in body. The trouble is one can’t think of much but the general futility of existence.

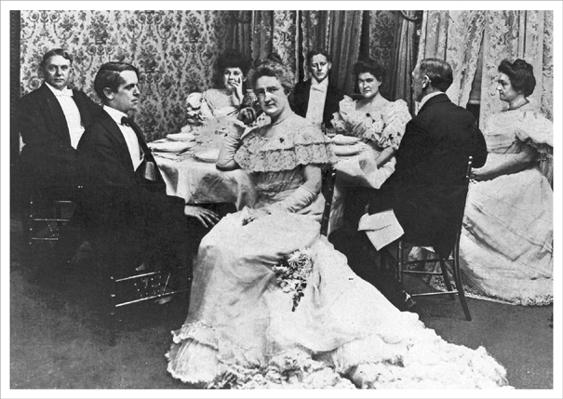

Willa Cather at the celebration of Mark Twain’s seventieth-birthday dinner. Cather is third from the right.

My love to you and your mother. I envy you a New England spring.

Yours always

Willa

The picture was of Cather wearing an uncharacteristically frilly dress when she attended a lavish dinner at Delmonico’s in celebration of Mark Twain’s seventieth birthday in 1905. Harper’s magazine devoted its December 23, 1905, issue to Twain, the dinner, and photographs of the guests in their finery.

![]()

In the spring of 1930, Woman’s Home Companion published Cather’s short story “Neighbor Rosicky.”

TO MARGARET AND ELIZABETH CATHER

March 19 [1930]

Las Encinas Sanitarium, Pasadena, California

Dear Twinnies;

Perhaps you’ve seen the first part of “Neighbor Rosicky” in the [“]Woman’s Home Companion”—but I am sending you the first and second parts in another envelope, in case you have not seen it. Your daddy will read it aloud very well, as he knows the characters.

Your grandmother is about the same,—comfortable, and most of the time cheerful. I am hoping to see you in a couple weeks, my dears. I will try to make my stay in Rawlins [Wyoming] on April 12th and 13th. I will let your father know later.

With love from all of us

Aunt Willie

![]()

In May, Cather and Lewis sailed for France. Cather needed to make this trip in order to complete Shadows on the Rock, but she also wanted to see her old friends Isabelle and Jan Hambourg.

May 24 [1930]

My Darling mother;

Yesterday Isabelle and I were walking in a park full of grandmothers and children and she, paying attention to the children, turned her ankle and fell forward and cut a deep gash in her knee on a stone. It bled a good deal. We took a taxi home, where I washed it with iodine and bound it up, but I found the flesh was badly torn, and as soon as Jan came home I sent him for a doctor. He said she must stay in bed for several days, as a tear is worse than a cut and may suppurate. Isabelle had a very serious illness in the winter and will have to be an invalid for a long while. It is very sad for me that the two people I love best in the world get sick thousands of miles apart, and I such a poor traveller! I have seen very little of the gay side of Paris as yet, we have been here only a week today, and for the first three days Edith was sick and had to stay in bed, and now Isabelle is laid low with this cut on her knee, and for part of the time I have had a rather queer “tummy” from strange water and worry and being tired. Tell Doctor [Stephen] Smith for me that living-conditions are much pleasanter at Las Encinas than in any Paris hotel I have yet found—even the food there is more to my taste, though French food is always good. In spite of every-one’s being below par physically, I have made two trips over to the queer old part of Paris where part of my new story lies, and have been well rewarded. That part of the city has changed very little, many of the same houses were there when my story-people lived there two hundred and fifty years ago. I went to church at the church they always attended. Many, many things are still the same.

Now I am going over to see Isabelle and be there when the Doctor comes to dress her knee—we will talk of you as we always do. She always wants to hear every little thing about you and the place you are in.

Lovingly

Willa

![]()

The next three notes were written on postcards of the Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris. Around the picture on the front of the first, Cather wrote, with an arrow to the bell tower, “The bells are in here,—still the same ones,” and, with another arrow and a reference to Victor Hugo’s Notre-Dame de Paris, “This is the parapet from which Quasimodo threw the wicked priest.” The second and third postcards feature images of Notre Dame gargoyles.

TO MARGARET AND ELIZABETH CATHER

May 28 [1930]

Paris

Dear Twinnies:

This is the glorious church of which you have read so much. It always looks to me much bigger than any New York sky-scraper. I have often walked about the high parapet from which Quasimodo threw the priest.

TO MARGARET CATHER

May 30 [1930]

Isn’t she a dreadful old bird? Awful to think she has been so full of spite for seven hundred years! I am sure all the figures were Quasimodo’s playfellows, and that he had special friends among them.

W.S.C.

TO MARGARET AND ELIZABETH CATHER

[June 1930]

Dear Margaret & Elizabeth;

There are countless figures like these perched all over the many roofs of Notre Dame. You have to climb all over the roofs and tower to see them all. They have been there since the year 1200, some before.

W.S.C.

June 30 [1930]

My Dear Blanche,

I have been very busy doing nothing for five weeks now and am beginning to get a little bored with it. I may go on to Vienna in a few weeks, or I may go home and up to Grand Manan, which seems to be the quietest spot in the world for work. It has been lovely to be so near Isabelle and Jan, we have done lots of nice things together, but I hate to be in a city in summer, even when the city is Paris, and if there is any really wild country in Europe I have never found it. The automobile has spoiled all that. When I first arrived everyone was having influenza, and I had it, too, for a week. I am very well now but I begin to long for green, quiet country. I’ve seen the Hambourgs and checked up on all my historical background, and I came over for those two things. If I decide to go home in August I’ll let you know.

With love to you and greetings to everyone in the office.

Yours

Willa Cather

TO MABEL DODGE LUHAN

July 1 [1930]

Paris

Dear Mabel:

I’ve been wanting this long while to write you that your article on [D. H.] Lawrence is the only thing I’ve seen which has any of him in it. Everyone else who put in an oar wrote about themselves, as people usually do, but you really wrote about Lawrence, and I got a thrill out of it.

Awfully nice of you to tell me that [Robinson] Jeffers liked the “Archbishop.” “Roan Stallion” is such a glorious poem. I read it in San Francisco and about went to see the man. The short one called “Night” seems to me one of the finest things done in English in many years.

Paris is almost as noisy and crowded as New York. It has changed woefully in seven years. I came only to see a dear friend who has been very ill. Both Edith and I are often homesick for New Mexico, in spite of the many gay things we are doing. I’m darned tired of being gay, to tell the truth. I’d like just to be a vegetable for a few months.

With heartiest love from us both

Willa

![]()

Through Jan Hambourg, Cather met the Menuhin family in Paris. The Menuhins—parents Marutha and Moshe, children Yehudi, Hephzibah, and Yaltah—were a gifted musical family who would become some of the most treasured companions of Cather’s later years. Yehudi, considered one of the greatest violinists of the twentieth century, began playing publicly at age seven. When Cather met him, he was fourteen years old.

TO MARGARET AND ELIZABETH CATHER

July 14 [1930]

My Dear Twinnies;

Naughty Elizabeth, who has not written to me! Nice Margaret who did! Yesterday I climbed up to the tower of Notre Dame again and spent the morning among my old friends, the gargoyles. The stairway is a circular one of white stone, and winds round and round a central column of white stone. It is very dark, lit only here and there by a slit in walls, and only then can one realize the great strength and thickness of the walls of Notre Dame and the huge blocks of cut stone of which they are built, stone fitted into stone with no cement.

Today is the anniversary of the taking of the Bastille in the Revolution, the greatest holiday of the year, and the people are dancing in the street before every little cafe. Late last night Jan and Isabelle drove us about in a taxi to see the dancers in all the little streets in the poor part of the city. Tonight we are all going to dine together at a gay restaurant—a lovely place where I went to lunch three days ago with Yehudi Menuhin the wonderful boy-violinist from San Francisco, and his family. He has two little sisters aged nine and seven who are almost as gifted and quite as handsome as he. They were in Paris only one day and we had a very exciting [time]. The one aged 7½ last winter wrote me a dear little letter about the “Archbishop”! All three have golden hair and skin like cream and roses—simply fairy-tale children. Their parents are nice, too, especially the mother.

I am enclosing a check for Virginia, to help with her college expenses, and I’m awfully pleased that she got the scholarship.

With my dearest love to you all

Willa Cather

How awful that they translate “Notre Dame de Paris” the Hunchback of Notre Dame!

TO BLANCHE KNOPF

August 21 [1930]

Grand Hôtel d’Aix, Aix-les-Bains, France

My Dear Blanche;

I have been gloriously doing nothing here for three weeks, after very interesting but rather tiring travelling in Provençe. I love Aix, and this year it is not at all crowded. I’ve always thought the cooking and pastry of Savoie the best in France, and, alas, I have picked up a couple pounds! I expect to sail on the Empress of Scotland, September 20, landing at Quebec and going straight down to Jaffrey, New Hampshire, to the old hotel where I always work in comfort and quiet. I dont want to go to New York until I have finished the last part of the book. I’ve been too lazy to work over here, and seeing too many old friends. I had two thrilling weeks motoring through the wild coast and mountains about Marseille—I’ve wanted for years to explore it.

The Hambourgs are now in Salzburg, at the Mozart festival, but they will meet me in Paris September 4th.

My love to you and Alfred and best wishes to everyone in the office.

Yours

Willa Cather

September 30 [1930]

aboard the Canadian Pacific S. S. Empress of France

My Dearest Dorothy:

Your letter, telling me of your mother’s death, reached me in Paris on the day before I sailed for home. Isabelle and I happened to have been talking of her the night before. I am sorry on your account, but almost glad on your dear mother’s. She was too keen and alert to linger in a clouded state—when she had a good day she must have felt that something had broken or given way, and that would have distressed her. When I last saw her, after her trip ’round the world, she was entirely and vigorously herself, all her colors flying. I thought she had not changed in the least. I am glad I can remember her like that. But these vanishings, that come one after another, have such an impoverishing effect upon those of us who are left—our world suddenly becomes so diminished—the landmarks disappear and all the splendid distances behind us close up. These losses, one after another, make one feel as if one were going on in a play after most of the principal characters are dead.

I have been in France since the middle of May and am now on my way to Quebec. From the middle of October I shall be in Jaffrey N.H. for some weeks and perhaps I can run up to see you some day.

My mother’s condition is unchanged. The doctors tell me she is so strong that she may live for five or six years in this state. Goodbye, dear Dorothy. I’m so sorry that you’ve had this break to face, but oh I’m glad for your mother and for you too that she was not punished by a long and helpless and utterly hopeless illness.

My love to you, from a full heart.

Willa

Sunday [October 5, 1930]

Chateau Frontenac, Quebec City

Dear Blanche and Alfred;

I was so glad to get your message at sea, and your good wishes for me were fully realized. I had a fine crossing, and anything more lovely than the approach to this continent by way of the St. Lawrence, when all the wild forests of its shores and islands are blazing with autumn color, I have never seen. I meant to go on immediately to Boston and Jaffrey, but I got rather a thrill out of journeying straight from Paris to Quebec, and as the weather is glorious I shall stay on here until Tuesday. My story comes to life as soon as I get back here and I get a good deal of pleasure out of playing with it. Books, alas, are like children,—never so much fun after they grow up and are finished as they are when they are merely things to play with and all your own. I’ve learned to get my fun before publication. I’ll write you soon from Jaffrey.

Affectionately

Willa Cather

![]()

In 1930, the American Academy of Arts and Letters awarded Cather the William Dean Howells Medal for Death Comes for the Archbishop. The medal is given every five years to honor the best book by an American writer published during the previous half decade. That same year, Sinclair Lewis became the first American to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Upon receiving her letter of congratulation, Lewis responded that he thought Cather ought to have been the recipient, and said that he considered A Lost Lady one of the very best books in American literary history.

TO ROSCOE CATHER

November 6 [1930]

Grosvenor Hotel, New York City

Dear Roscoe;

Gold medal very large and handsome—weighs several pounds—gold with no alloy at all—handy for a paperweight. I’m going to take it to [the] bank to have it weighed and valued. It’s one thing you can turn into money—one flattering phrase that’s worth something!

I send you a very good editorial from the N.Y. Times, and I think that is just why Lewis got the Nobel award. We look like that to Europe, and all those Swedish chore boys we kicked around are telling us what they think of us. I expect we really are like that. Anyhow, I like Lewis and I wrote him that though I couldn’t honestly say I’d rather he got the award than I, I’d rather he had it than anyone else. The newspaper discussed the award so much that thousands of good people think I did get it, and my mail is full of dozens of begging letters from preachers and widows and orphans; “please help me with just a little of that $47,000”!

I send you a copy of Judge [Robert] Grant’s speech made in conferring the medal. You might send it and the newspaper clippings to Elsie. She might be interested to see them and I have over two hundred letters to dictate before I can begin to work, or even have my tooth filled, so I’ve not much time for family correspondence.

Mr. [George] Whicher of Amherst was to bring Virginia and Tom up to dine with me in Jaffrey on the first Sunday in December, but this medal affair called me away before my appointed time, and now I won’t get back. I’m going to Philadelphia for Thanksgiving, to some old friends who will give me some dinner and a bedroom and study—and let me alone.

With much love to you and yours

Willie

Send the checks to me at this address, please

![]()

At the ceremony where she received her Howells medal, Cather met the American sculptor and writer Lorado Taft.

TO LORADO TAFT

November 17, 1930

New York City

My dear Mr. Taft:

As I had to leave the platform before the exercises were over last Friday, in order to catch a train, I did not have an opportunity for a short conversation with you. Though I was alone with you for a few moments before the program began, you were then occupied with the address you were soon to deliver. I simply wanted to tell you how much pleasure your fountain near the Art Institute in Chicago has given me for many years. I have to go West two or three times every year and I never go through Chicago, even when the interval between trains in short, without taking a cab and driving over to the Art Institute for another glimpse at that fountain. It always delights me. There is in it everything that I feel about the Great Lakes, and it always puts me in a hopeful, holiday mood. I do not know whether you yourself think it an especially fine thing, but I do. I do not know why I like it so much, because I know very little about sculpture. But it seems to me that the pleasure one feels in a work of art is just one thing that one does not have to explain.

Very cordially yours,

Willa Cather

January 14, 1931

My dear Mr. Bain:

Yes, of course I get a great many “fan” letters as you call them—but most of them are pretty thin wind, I assure you. It is very easy to pick out the real ones. Of course, as you intimate, it is a very distinct disadvantage to be a Lady Author—anybody who says it isn’t, is foolish. Virginia Woolf makes a pretty fair statement of the disadvantages [in A Room of One’s Own]. But young children are neither very male nor very female, and I find that the impressions and memories that hang on from those early days of having no particular sex, are the safest ones to trust to—and the pleasantest ones to play with. I am glad you liked the two particular books you mention—but myself I always feel that “A Lost Lady” is, artistically, more successful than either of them.

Cordially yours,

Willa Cather

January 14, 1931

Dear Norman Foerster:

No, I cannot accept your kind invitation. I simply never give lectures or talks of the kind you suggest. I used to, very occasionally, but since my mother has been an invalid I have had no time for these things.

I have not written you before because I have wanted to write you a long letter about your book [Toward Standards: A Study of the Present Critical Movement in American Letters], and Heaven only knows when I will have time to do so. I am just finishing a new book of my own and will soon go to my mother in California. I read your book very carefully and with great interest. I am awfully glad you wrote it, and I agree with you in the main—in your opinions on the history of criticism and the critical mind, but I do feel that you take a little group of American critics, I might say of New York critics, too seriously. This of course is entirely confidential, but I think of the men you mention, Randolph Bourne and, in a less degree, [Henry Seidel] Canby, were the only ones who had that instantaneous perception and absolute conviction about quality which a good critic must have. You understand me; it is a thing like an ear for music. You can tell when a singer flats, or you cannot tell. You cannot be taught to distinguish that error.

Take, for example, an intelligent and serious man like Stuart Sherman. (And please don’t think there is anything personal in this—he always treated me very generously indeed.) I knew him quite well. He was absolutely lacking in the quality I speak of. He could take a writer as a subject; talk about him and read about him and worry his brain over the matter, and say a great many interesting things about this writer—many of them true. But it was all from the outside. It was a thing worked up, studied out.

What I mean is this: suppose that Sherman had read all the novels of Joseph Conrad except the “Nigger of the Narcissus”, that he had written about them and read what other critics had to say about them until he knew a great deal about these books and their quality. If all this were true, and I had taken a dozen pages from the “Nigger of the Narcissus” and mixed them up with a dozen pages written by Conrad’s fairly intelligent imitators (people like Francis Brett Young for example), it would have been utterly impossible for Stuart Sherman to pick out the Conrad pages from the second rate stuff.

A fine critic must have something more than a studious nature and high ideals, and the very best criticism I happen to know was not written by professional critics at all. Henry James was a very fine critic I think; and so was Walter Pater. And so was Prosper Mérimée (Do you know his essay on Gogol? That’s what I call criticism!).

I don’t mean that all fine artists in prose have been good critics. Of course Turgenev was a very poor critic.

But on the whole, composers are the best judges of new musical compositions and writers are the best judges of new kinds of writing. I mean they are better judges than either musical scholars or literary scholars. But this is only a little of a great deal that I would like to say to you about your book, which does exactly what a book of that sort ought to do—makes me want to come back at you and have it out with you, both where I agree and where I disagree.

Always cordially yours,

Willa Cather

January 20

P.S. This letter was written some days ago—but my secretary [Sarah Bloom] begged me not to send it. “Just the sort of indiscreet letter that falls into the wrong hands and makes you a lot of enemies for nothing,” says she. However, as she has gone to Cuba for her vacation, I think I’ll send it anyhow. I feel that it won’t fall into the wrong hands, and that you won’t quote me—even to your publisher, who is rather a chatter-box.

Yours,

Willa Cather

January 14, 1931

The Grosvenor Hotel, New York City

Dear Mrs. Grippen:

Excuse delay in replying to your letter. I have been travelling. I think I can enlighten your perplexity. Myra Henshaw [in My Mortal Enemy] before her death came to consider Oswald as her “mortal enemy”;—she came to believe that anything loved selfishly and fiercely and extravagantly became the enemy of one’s soul’s peace. Please tell your ladies that that simple fact is the subject of the story.

Very cordially yours,

Willa Cather

![]()

Knopf published Mabel Dodge Luhan’s memoir of D. H. Lawrence, Lorenzo in Taos, in 1932. Cather read the book before it was published, the same way she read Luhan’s personal memoir, Intimate Memories.

TO MABEL DODGE LUHAN

January 17 [1931]

35 Fifth Avenue, New York City

Dear Mabel;

I’ve just finished “Lorenzo in Taos” with great admiration. It’s as good as the Buffalo part of “Intimate Memories”. It’s like a big canvas full of gorgeous color and thrilling people—and motion. It’s the constant changes in the personal equations and in the emotional climate that make the book so exciting. Everything that goes on between the people is unexpected and unforeseen, as things usually are in life and so seldom are in the pages of a novelist. I don’t always agree with you in your interpretation of your people and their motives, but I always agree with the way it’s done—with your presentation of your own interpretation, I mean. Everybody in the story is alive and full of behaviour—except a few colorless people whom you have the good sense to let alone. Perhaps you’re a little hard on Frieda [Lawrence], a little hard on [Dorothy] Brett—but you’ve made ’em as you saw ’em and they and all the rest keep the ball rolling. You’ve done Tony [Luhan] magnificently! I wouldn’t have thought anybody could do him so well. It’s splendid, and not over-done. And you’ve done yourself better than anywhere except in the early Buffalo volumes. In the Italian part of the memories I always felt that a stream of interesting people went across the page but that you as a person disappeared. Here you re-appear with a bang! I imagine that it’s because your eye is fixed on Lawrence and you do yourself rather incidentally that you succeed so well. It’s amazingly spontaneous and amazingly true. I’m sure it’s the best portrait there ever will be of Lawrence himself. I’m amused at your struggle with his giggle. Was it a giggle? Wasn’t it more like a snicker? Not snigger, but snicker? To me giggle is always fat and jolly.

I simply love the way you do the Taos country and the weather. When I was writing about it in a very formal and severe manner, as befits the eye of a priest and the pen of a stranger, I kept thinking that I would love to see it done intimately, as part and parcel of somebody’s personal life—not a background! (about once a week I get a letter from some puppy who tells me he has done a story of sophisticated easterners in a New Mexican background, or some other kind of simper with a New Mexican background.) I wish to God I could have put the Archbishop in Kansas or Nebraska—not many sensitive artistic natures have the grit to follow you there. It’s a great advantage to work in a part of the country that is distinctly déclassé—it rids you [of] superficial writers and superficial readers. But this is a long departure. When a country like the Taos country is really a part of your life, and when your life is a form of living and not a little camera,—well, then it all works up very stunningly together. Few things have ever given me more joy than the night you all spent chasing about in [the] alfalfa field. Why Tony’s car becomes a positive god of vengeance, a frightful threat to the foolishness of all of you, and to a whole school of thinking that has upset the old balance of things, where personal desires and emotions were masked under a National consciousness or a tribe will, or the particular false-front of any ones social period.

Edith is in Boston for a week, or she would probably be writing you at the same time. She read Lorenzo through before she left.

I’ll be leaving for California in a few weeks, to join my mother. Her condition is about the same. The doctors tell me it may go on five or six years like this. She seems to get pleasure out of being with us, even in such a wretchedly helpless state. I have to stop off in San Francisco, so I’ll probably go over the northern route. But my next long trip will be to Mexico City. I’m envious that you’ve beat me to it.

With heartiest congratulations

Willa Cather

February 19 [1931]

The Parkside, New York City

My dearest mother:

Just a word to you from this hotel where I am waiting for Mary Virginia to come to dinner with me. Thank Douglass for his reassuring telegrams. Indeed I will get to you just as soon as possible—that will be very soon now.

My book is done! My publisher went to Paris soon after Christmas when the book was only about two thirds done. We rushed copies of the manuscript on to him some weeks ago, and he read it in Paris and sent me this cable for a Valentine. Everyone at the office likes it better than “The Archbishop.” I do not like it better, but I think it as good a piece of work.

I am now reading the proofs—Douglass will explain to you what that means, and I am correcting many mistakes—some are the fault of the printers, and some are my own fault. It is so easy to make a little slip in a book so full of dates and historical happenings. One simply has to get them right.

But it won’t be long now until you get a telegram telling you by what train I am coming. I expect to leave New York on the fourth of March, and will go straight through, stopping one night in Chicago to rest.

Here comes M.V. so goodbye with much love from us both

[Unsigned]

TO JOSEPHINE GOLDMARK

March 3, 1931

My dear Miss Goldmark:

I had so counted upon having a long evening’s talk with you about your book [Pilgrims of ’48: One Man’s Part in the Austrian Revolution of 1848, and a Family Migration to America], but the serious illness of two of my friends has cut my winter all to pieces, and now I am hurrying off to California because my mother’s condition has changed for the worse.

It is very difficult to tell you in a letter about the things which delighted me in your book—not this chapter or that, but the whole thing, moving along with such a refreshing calm and such an absence of that nervous tendency to force things up. I read it slowly evening after evening, and it was like taking a long voyage with a group of people who have become one’s friends by the time one reaches port. I enjoyed the Brandeis family as much as the Goldmarks, and Frederika is surely charming enough to give a perfume to any book. What a charm and distinction there is about the personality of your mother as she appears in this book—I wish I could have met her. I am so interested in the daguerreotype picture of her—I think your sister Pauline looks very much like her.

You see, I have known a great many of those German and Bohemian families myself, in the West, three generations of them living together in little towns. I have watched the original pioneers growing old and the third generation growing up, all getting rooted into the soil and interweaving and becoming a part of the very ground. I began to watch it as a young child—it delighted me even then, and keeping in touch with those communities and watching the slow flowering of life has been one of my greatest pleasures. Your book brought it all back to me; the slow working out of fate in people of allied sentiments and allied blood. These many characters influencing each other by chance give a book a greater unity than any plan you could have made. As I have already said, reading it was like taking a long voyage with a group of people whom one likes so well that one is sorry to come into port. They have everything that was nicest about the old world and the old time, and I put your book down with a sense that even if I do not like the present very well, we have had a beautiful past.

With very deep gratitude for the happy evenings I spent with your Pilgrims of ’48, for the memories they awoke and for the hope they give me for the future, I am

Your very true friend,

Willa Cather

[March 12, 1931]

Crossing Kansas

Dearest Irene;

This morning I wakened wondering if you were awake—I had been dreaming that you and I were on the Burlington, going out to the Golden Wedding together! At first I felt sad—then very happy. I did not really deserve that happy time. I had never been a very thoughtful daughter. My mind and heart were always too full of my one all-absorbing passion. I took my parents for granted. But, deserving or not, I had it, and there is no one in the round world whom I would have chosen before you to share it with me. You were just the right one, and I shall always be thankful for that trip we had together back to our own little town. I’m glad nobody met us at Hastings. I remember every mile of the way home, don’t you? And the bitter cold in which we left Chicago? You see you are the only person who reaches back into the very beginning who has kept on being a part of my life in the world where, for some reason I have to go on and on, from one change to another. The other friends, Isabelle and Edith and Mr. McClure and many others, don’t go so far back. And the dear Red Cloud friends (Carrie and Mary dearest of all) have not been so much in my later life as you have. With you I can speak both my languages; you know the names of all the people dear to me in childhood, and the names of most of those who have grown into my life as I go along. I suppose that is why I crowd so much information about the MENUHINS and the new friends on you. I want somebody from Sandy Point to go along with me to the end. My brothers are loyal and kind but they are not interested in these things. I feel so grateful to you for having kept your interest. Carrie and Mary are so loyal to our old ideals, but they have not been in my later life so much as you, geography, long distances have been against us. I am always so glad Mary and Doctor [E. A. Creighton] were in New York that winter, and of course came to tea and met my friends.

When I go back to Red Cloud to stay for a few months sometime, you must come; Mr. Weisz must surely spare you to me for a little while.

So lovingly

Willie

This train jumps about so—I’m afraid you won’t be able to read this scrawl at all.

March 17 [1931]

Las Encinas Sanitarium, Pasadena, California

Dear Sister;

I won’t write you a letter until I return from San Francisco and am more settled in mind. Mother has failed so much since I last saw her, but she does have some hours of restful quiet each day, I think. She is not in pain—just the weariness and discomfort of every physical act growing harder and harder. Sometimes she is quite cheerful for an hour, and she goes out in her chair every day and wants to go.

I am going up to San Francisco to take a Doctor of Laws at Berkeley, and devoutly hope that someone here will move out of a cottage while I am away. I am in the main building, next the dining room, and don’t get much rest.

I don’t think you could help much if you were here, dear. Mother is conscious, but her perceptions are so dim—with occasional hours when she seems to understand.

Mrs. Bates is so good to her, and so consciencious, and Douglass I think does more for her than any man ever did for any woman since the world began.

With love

Willa