When a wild creature comes close because it chooses to, we can see more clearly into its world; a world unclouded by fear is more transparent, more easily understood.

MARK AND DELIA OWENS, Secrets of the Savanna

Late one balmy July afternoon aboard ship in The Bahamas, we saw a very active group of dolphins. They were leaping and splashing and rolling all over each other in the distance, and they were headed our way. We were here to videotape them underwater. . . so we jumped in and waited for them to arrive. First our ears were assaulted by a loud and disparate “parade” of harsh sounds: squawks, intense whines, and shrill whistles. Within seconds, more than thirty dolphins zoomed toward us, twisting and curling around one another—torpedoes with minds of their own! They stopped abruptly, within an arm’s length in front of us. With their jaws clapping, they separated and faced off from one another, head to head. Then, as pairs and triplets, like underwater street gangs, these dolphins tail kicked, rammed, charged at, and bit one another: the ensuing mêlée seemed a confusing jumble. The vast array of vocalizations continued intensely. Adrenaline was most certainly running high, and not just in the dolphins! Yet just as swiftly as they had darted into view, the fighting stopped. The dolphins simultaneously became almost silent and, within their little gangs, began caressing and rubbing one another. Without exception, all the members of these little groups were placing their flippers on each other’s sides. And then, almost as abruptly as it ceased, the “fighting” resumed about two minutes later. This alternating pattern of fight and caress, fight and caress continued for the fifteen minutes they were in our view. In this context, it seemed as if the dolphins’ gentle touch and pectoral fin placement to one another’s side was reaffirming their friendship and fighting allegiance.— Kathleen

Listening to dolphins vocalize underwater is like being submerged within a highly orchestrated, yet flowing cacophony of sound. Fluid, high-pitched whistles seem to explode and then evaporate on the current. Abrupt chirps and squeaks, along with staccato squawks and creaking-door clicks, cause your eyebrows to rise and make you chuckle (which can leak water into your underwater mask if you’re not careful). When a dolphin turns toward you and explores you acoustically with echolocation, you may even feel the buzz of sound waves in your bones and muscles, as you reveal more detailed aspects of your physiology to the dolphin by sound waves: more information than the eyes can see. While vocalizing, dolphins may be motionless or may coordinate their sounds with a plethora of movements ranging from subtle postures to dramatic aerial leaps. Despite the sometimes-dramatic differences between the senses of dolphins and humans, eavesdropping on dolphins gives us a window through which we can imagine what their communication is really like.

When we ordinarily think of eavesdropping, we usually think of someone listening to a conversation without being observed—from behind a closed door, around a corner, or on a telephone extension. Remaining undetected allows us to learn much information from, and about, others. But snooping on dolphins is a whole different story than eavesdropping on a sister’s phone conversation. Eavesdropping on another species is not always easy, especially when dolphins can usually detect us well before we detect them. Furthermore, dolphins live a graceful, mobile existence in a fluid world in which we are—at best—capable but relatively clumsy. Fortunately, we can eavesdrop on dolphins even when our presence is known simply by establishing ourselves as discreet, noninvasive, predictable, and—frankly— boring. In this sense, dolphins learn to habituate, acclimate, or at least tolerate human presence. Eavesdropping is one of the best ways for us to learn more about dolphin communication and social life.

Since the early 1960s, many scientists have pursued the systematic study of communication in animals. A researcher’s ability to eavesdrop on his or her subjects has become an invaluable skill. The most famous researcher in this regard is Jane Goodall, who pioneered scientific eavesdropping of another species by gaining the tolerance, trust, and acceptance of a group of chimpanzees in Tanzania in the 1960s.1 Katy Payne discovered elephant infrasonic (frequencies below human audible sound) communication literally by feel.2 Before Payne and her colleagues made this discovery, no one knew how, or if, elephants coordinated and met up with one another over long distances. Now researchers can record these infrasonic elephant conversations using sophisticated microphones without even being near their subjects—the ultimate in eavesdropping.

As much as we try to be discreet dolphin voyeurs, we must remember not to become overzealous paparazzi in our quest to learn more about them. It is sometimes hard not to feel like a well-intentioned stalker with video or still camera (sometimes both) in hand while in the water with dolphins. This situation, however, is not nearly as surprising as finding oneself surrounded by the same dolphins we are trying to observe unobtrusively.

Sometimes curious and playful, possibly lonely, and even mischievous dolphins are not always content with researchers simply being subdued passive observers, which presents both challenges and opportunities. As was told in the days of Greek myth, dolphins are unique among wild animals in that individuals will from time to time approach humans socially, even without being offered food. Interacting with dolphins can at times teach us about how they communicate with one another, which we detail later.

People have been interested in communication between nonhuman animals for centuries for more than scientific purposes. By recognizing alarm calls used by, for example, vervet monkeys to alert one another to the presence of predators, indigenous peoples learned to avoid shared predators. Familiarity with the behavior of potential predators also helped humans avoid becoming a menu item. For example, becoming more aware of the signals that domestic dogs exchange can be helpful in detecting the more subtle indications of a dog alerted to an intruder (before the dog barks) and of a dog intending to bite you (even before the dog growls).

A dolphin looks so graceful that it is hard to imagine that its body has been shaped for life in water rather than beauty.3 The aquatic environment has extensively sculpted how dolphins communicate with one another. As we discussed in chapters 1 and 2, they have an impressive variety of signals and a remarkable range of hearing and sound production capabilities. These abilities seem to have been adapted to each species’ habitat. River dolphins often live in murky waters and are known to have relatively poor eyesight but exceptional echolocation aptitude. It is unlikely that river dolphins would rely on visual communication as much as the use of hearing and sound production, although this hypothesis remains to be tested. Conversely, Atlantic spotted dolphins in The Bahamas usually swim through water with visibility at least ninety feet (about thirty meters) in depth; Kathleen’s studies show that they produce only about a third the number of whistles as the Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins found around Mikura Island, where visibility is generally not as clear underwater. Thus, at distances where they can see one another, dolphins seem to rely more heavily on visual, behavioral, and postural cues than on auditory cues to exchange information.

Postures or gestures are distinct visual displays and are useful for close-range communication among dolphins. Visual signals provide an alternative to or work in synergy with acoustic signaling. Coloration and other physical characteristics of the dolphin body can modify and expand how they share information, as well as what specifically they might be trying to convey to peers. Body coloration, body size, fin shape, and other physical features can reveal age, gender, reproductive status, and species or be a component of communicative signaling. Although the length and shape of their limbs have been modified for swimming, dolphins are adept at using subtle shifts in posture or slight body movements to convey information in their three-dimensional world. For instance, aggressive threats in dolphins are often expressed through a direct horizontal approach that can be coupled with jaw claps, head shakes, body hits or slams, or the emission of a bubble cloud.

During fights, dolphins may orient themselves head to head and flare out both flippers in an exaggerated way. This makes the dolphin look bigger and may work to scare off an opponent.4 The group of fighting spotted dolphins described above featured many types of flipper use: they were flared, used in affectionate contact between “gang” members, and guided their swiftly moving bodies as each dolphin careened around the others while delivering swift tail kicks to opponents. For most dolphin groups, when fights are observed, the gangs are actually pairs or triplets of males vying for access to a female for mating. This group of spotted dolphins, however, has defied complete classification because juvenile, subadult, and adult males as well as females were involved. Maybe they were irritated over some other aspect of social life. . . Could they just have been ornery? Or was there a disagreement over a foraging site? Additional observations of similar activity in other dolphins or watching this video for more hours might shed more light. Still, this fight and caress sequence illustrates how one action can have different meanings depending on the context or ensuing activity of the individuals as a whole. Flipper flaring by dolphins seems to function similarly to ear flapping by elephants.5 Flaring out one flipper (or one elephant ear) during nonaggressive or nonthreatening interactions sends a very different message. Perhaps the flare signifies affection, as compared to the increased size that the double-pectoral flare is likely to convey.6 When a dolphin swims, the flippers give the dolphin a more refined directional control. A slight shift in the angle held by a dolphin’s flipper might signify a change in swimming direction to others in the group. Thus, the similar action of the flipper used in a different situation may send a different message to receivers.

Even though she refuses to set foot on a boat or to swim in the sea, Umi the mighty sea beagle has guided Kathleen many times as she reviews whistle data from the dolphins around Mikura Island, Japan.

Have you ever felt as if you were going around in circles? Dolphins must share that feeling. At least, dolphins often seem to circle people swimming near them. We have both witnessed these acrobatic spinning sessions. A typical spinning scenario usually involves a single, relatively young dolphin swimming in increasingly tighter circles around a person who awkwardly spins around with the dolphin. In this way, we have found ourselves becoming our own “subjects.” Although this circling behavior is not uncommon among dolphins, especially during play, it seems more common during interactions with swimmers. Perhaps this is because humans are simply less agile in the water, which makes us prime targets for amusement by dolphins in need of cheap entertainment.

Conversely, perhaps this circling behavior manifests differently when it occurs with a dolphin partner. We imagine the ballet between two spinning dolphins to be like a pas-de-deux in Swan Lake, as opposed to a George Carlin show, which could characterize the human-dolphin spinning pair. Still, we have a sneaking suspicion that there is a bit of mischief on the part of the dolphins who engage in circle swimming—especially since juvenile dolphins are so frequently the perpetrators. Or could the circling behavior be an attempt to communicate something visually to peers or maybe to the humans involved? We have tried to analyze this behavior from videotape rigorously—counting how many times it happens and even attempting to find meaning in whether the dolphins circle clockwise or counterclockwise. In one study, Toni found that these “circle the human” bouts occurred 7 percent of the time that spotted dolphins in The Bahamas accompanied human swimmers—but the meaning of which direction they circled was not apparent (perhaps it is a matter of left- or right-handedness?).7 Clearly, the dolphins have had us “going in circles” out of the water as well as in it.

From their blowhole, dolphins blow a variety of bubbles ranging in size from thin streams of tiny bubbles to trails of larger, more oddly shaped bubbles to the largest bubble clouds, produced when dolphins are fighting. The function of these bubble emissions is only recently being better understood.

There are certainly other times when the observer becomes the participant. In an episode that could easily be called “who’s watching who?” I (Toni) fondly remember an afternoon with other people on a boat trip in The Bahamas when one male passenger posed as Poseidon with a boat pole as his trident and a handcrafted seaweed crown on his head. We didn’t know that a spotted dolphin was lurking below the water surface watching us. After several minutes, the seaweed crown was inadvertently tossed into the sea. And soon we saw the dolphin wearing the crown in a parody of sorts of our behavior.

Visual signals often become tactile signals, especially in cases where underwater visibility is limited. Dolphins are exceptionally tactile; where and how dolphins are touched conveys different levels of information, or signal content, to their peers. Extensive contact and rubbing occur in both captive and wild dolphins during play, sexual and social activity, between mothers and their calves, and among juveniles. Dolphins use their rostrum, pectoral fins (flippers), dorsal fin, flukes (tail), belly, and even the entire body when touching one another.

I (Kathleen) am particularly fascinated with the exchange of touch between dolphins and, for several years, have been investigating how dolphins might use flipper contact (touches and rubs) to communicate on different topics with peers. I have collected data on wild Atlantic spotted dolphins in The Bahamas, wild Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins around Mikura Island, and captive bottlenose dolphins at the Roatan Institute for Marine Sciences (RIMS) in Honduras. While swimming among dolphins and applying the same protocol for observations of both captive and wild dolphins, I use a mobile video/acoustic system to gather behavioral and audio data. Where on the body, with whom, and during what context a touch or rub occurs significantly affects the meaning of a flipper contact exchanged between dolphins. An excited calf can be calmed by a mother’s pectoral fin, but that same flipper can also discipline a more rambunctious youngster when needed.

A subadult spotted dolphin delighted in the discarded seaweed wreathe that humans had been playing with aboard ship just a few minutes before. The dolphin frolicked and enjoyed her seaweed crown and seemed to imitate the human antics she had stealthily observed.

In my study of flipper contact, I needed to create behavioral definitions so that other scientists could follow my procedures or replicate my methods, if needed. And referring to the “dolphin whose pec fin touched the second dolphin’s body” was wordy and growing tiresome. So, in my new behavioral vocabulary, the rubber is the dolphin whose pectoral fin touched a second dolphin’s body, while the rubbee is the dolphin whose body was touched by another dolphin’s pectoral fin. (These terms have produced plenty of chuckles during scientific presentations!) Either the rubber or rubbee can initiate or receive flipper contact. As I collected data and observed how dolphins touched or rubbed one another with their pectoral fins, I began to see patterns in the data and subtle differences between the two wild dolphin groups. Older bottlenose dolphins at Mikura Island shared more pectoral fin contact, whereas younger spotted dolphins in The Bahamas engaged in more flipper touches and rubs. In fact, dolphins from both groups seemed to choose their contact partners; same-age, same-sex pairs shared more rubs and touches than other pairings. In addition, the rubbee seemed to initiate more contact among the dolphins at Mikura Island, whereas the rubber engaged in more contact among spotted dolphins in The Bahamas. I’m still not sure about the age difference between both dolphin groups, but I think that the rubber-rubbee differences might be explained by environmental factors. Rubbees may solicit more contact from rubbers at Mikura Island because these dolphins do not rub against the rocky boulder bottom as much as the spotted dolphins rub on the sandy sea floor in The Bahamas. I remember that for every entry to swim with and observe spotted dolphins, there was at least one dolphin rubbing its body into the soft sand.

Dolphins often share pectoral fin rubs where the flipper contacts have a specific meaning. The dolphin rubbing her pectoral fin along the side of another dolphin between the flukes and dorsal fin is asking for something. That something depends on the ensuing activity but might be continued rubbing behavior or maybe even for help in a fight.

With these unexpected, subtle differences observed among two wild dolphin groups, I was intrigued to see what I would find when I began my studies of the captive dolphins at the Roatan Institute for Marine Sciences. Besides looking at how dolphins share pectoral fin contacts, I made “blind” observations of each dolphin trainer with each dolphin at RIMS. I was curious to see whether any patterns in behavior that I observed among the dolphins might be affected by their interaction with the trainers; if a dolphin did not use much pectoral fin contact with other dolphins, did that dolphin use more or less or the same amount with a person? The trainers did not know that I was occasionally documenting, or eavesdropping on, their contact with dolphins during training sessions. It turns out that the trends in behavior that I documented among the dolphins held true in their associations with their trainers. If a dolphin engaged in frequent tactile contact with other dolphins, that individual was also likely to solicit more touch from their trainer, and vice versa.

Somewhat surprisingly, I also found many more similarities in touches and rubs between the dolphins at RIMS and both wild dolphin study groups. This is the most fascinating part of behavioral science—just when you think you have the answer, an alternative explanation pops up for consideration.

Body rubs and other contact are also important: whether traveling, resting, socializing, or playing, dolphins are often seen in physical contact with other dolphins. Contact between dolphins can be modified to increase the information content: who, where, and how animals touch, as well as the intensity of a touch, factor into a signal’s meaning. Going back to the play-versus-fight scenarios illustrates this point. During play, hits, harsh sounds, bites, and other aggressive actions are modified by oblique angles of approach and frequent affectionate rubbing to indicate that the ongoing activity is playful and not seriously aggressive.

Dolphins often travel in contact with one another. They are very tactile and will rub each other’s bodies as they swim through the water.

Dolphins leap for a variety of reasons. They spin, somersault, perform back and front flips, and more as they glide through the air. Dusky dolphins are known for three types of leaps, while spinner dolphins are named for their high spinning leaps.

When a dolphin leaps from and then reenters the water, its body hitting the sea surface creates a sound that can carry for several miles. This breaching or leaping behavior often indicates general excitement deriving from any of several causes, including sexual stimulation, location of food, a response to injury or irritation, or the need to remove parasites. Dusky dolphins are well known for three types of leaps they exhibit in association with three stages of cooperative feeding: headfirst reentry leaps, noisy leaps, and social, acrobatic leaps.8 The last two create sounds that probably signal the state of activity to peers. Since these leaps occur nearer to the end of feeding, they may signal the shift from “dinnertime” to “dancing.” Noisy leaps could also act as a sound barrier to disorient prey and keep them tightly schooled—a signal that is to the dolphin’s benefit, if not to the fish. Spinner dolphins, on reentering water after a spin, a breach, a back slap or a head or tail slap, generate omnidirectional noise that travels over short distances. The leaps and spins of spinner dolphins seem designed to produce this noise, because these actions commonly occur at night, when visual contact is limited.9

When conveying a sense of threat or frustration, dolphins will tail slap the water dozens of times, creating loud, low-frequency underwater and aerial sounds.10 Just as you would not approach a growling dog, it is best not to approach a tail-slapping dolphin. The same goes for dolphins exhibiting an “S-shaped” posture, which can be followed by aggressive behavior.11 But both of us have witnessed S-postures and tail slaps used in nonaggressive contexts, too. For instance, juvenile spotted and spinner dolphins practice S-postures and tail slaps when playing, and dusky dolphins use tail slaps to corral fish for group feeding.12 As we saw in chapter 2, the percussive sound of a jaw clap accompanied with a direct approach or an aggressive posture is also a threat or warning signal. The social functions of nonvocal acoustic dolphin signals appear to be limited mainly to long-range communication to regroup with peers or as expressions of excitement, annoyance, and aggression.

Dolphins often couple nonvocal acoustic cues with other behaviors to exaggerate a signal and its message. Sometimes two or more male bottlenose dolphins will herd or corral a female to mate with her.13 Not only do the males create loud jaw pops, but they tail slap near the female, push and hit at her body, and approach her aggressively. A female pursued with these signals is unlikely to misunderstand her suitors’ intent.

The emission of bubbles from the blowhole may serve more as a visual signal than an acoustic one. Some researchers use a bubble stream that occurs with a whistle as a cue to identify a vocalizing dolphin from within a group.14 Unfortunately, no study has examined how dolphins might use bubble streams in relation to sounds. We do know that juvenile dolphins often emit bubble streams from the blowhole when they appear excited. When we are studying dolphins underwater, juveniles seem more interested than older animals in us. Young dolphins are inquisitive and often emit streams of bubbles while whistling. Could these bubble emissions be related to age—that is, are excited youngsters “leaky”?

Dolphins assume an S-posture as adults when they are fighting. Juvenile dolphins practice the S-posture when playing with other young dolphins. The rostrum is pointed up, the back is down, the peduncle is up, and the flukes are down, creating an “S” shape.

As we saw in chapter 2, dolphins produce all their vocal sounds by passing air back and forth between four sets of air sacs behind their melon. Maybe refined control of the air sacs, and thus bubble production, comes with age? Alternately, maybe the bubbles have a behavioral role. Dolphins produce many types of bubbles: bubble streams, bubble trails (slightly larger bubbles than streams), and bubble clouds. It is possible that bubbles sometimes function as a tool. Dolphin vocalizations can be powerful and painful: dolphins may use sound to injure the fish on which they prey.15 They might do the same to one another. Bubble clouds may form a shield that deflects an opponent’s aggressive, percussive sounds. The sounds are reflected off the air pocket created by each bubble cloud and away from the defending dolphin.

Bubbles likely have an array of functions depending on the activity and relations of the dolphins involved. We have both seen dolphins emit large underwater bubbles (befitting a cartoon caption) immediately after experiencing a novel or attractive sight or sound. Toni saw this often with dolphins who accompanied certain boats and swimmers. The dolphins sometimes emitted a bubble burst immediately after hearing a sound such as the splash made by someone jumping into the water or a boat engine revving. These bubble bursts happened so predictably with one gregarious and curious dolphin that we dubbed him the “cartoon character” dolphin.

Dolphins do not use their vocal cords to make sounds, yet they make an incredible variety of sounds that emanate from their head (see chapter 2 for details regarding dolphin sound production). These sounds are broadly divided into clicks, which include “pulse” sounds, and whistles. The sounds can be powerful, and dolphins are capable of fine control of the intensity of their vocalizations. All toothed whales make click (pulsed) sounds. High-frequency click trains constitute dolphins’ echolocation or sonar, which they use to investigate their environment and locate food. Because not all dolphins whistle, the use of clicks or echolocation for communication cannot be ruled out. Other mammals also have the ability to communicate using pulsed sounds or clicks: bats are specialized to use echolocation in air and have evolved specialized ear and nose leaves to help focus, direct, and collect sounds.16

Click trains with high repetition rates are called burst-pulses. In burst-pulses, the clicks are emitted so quickly that to the human ear they resemble continuous sound rather than a series of clicks. Squawks, whines, barks, and moans are examples of these sounds. It seems that burst-pulses are used to communicate among individuals rather than to discern information about the environment. We have seen dolphins emit squawks, whines, and barks when playing and fighting.17 These harsh sounds probably indicate excitement or frustration. The directional characteristics of many pulsed sounds, the relative ease with which they can be localized, their variability, and perhaps the power (that is, not only the intensity of the sound but the tactile effects of a loud, powerful sound) with which they can be produced enhance their value and usefulness as communication signals.

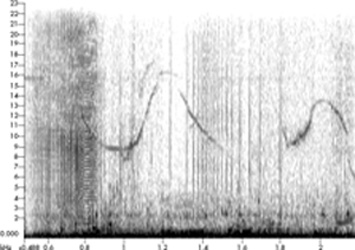

Echolocation clicks and squawks are shown on this spectro gram. Dolphins squawk when they play or are fighting.

Another possibility for dolphins to exchange information via pulsed sounds may be through passive communication—that is, eavesdropping on other dolphins. This term is perhaps misleading; we are referring not to what people know as eavesdropping but rather to “echoic eavesdropping,” which dolphins might use to share information. One individual might listen to a nearby dolphin’s clicks and associated echoes toward an object rather than produce its own click train. After all, it takes less energy to listen than to click. Alternatively, dolphins might listen rather than produce clicks to avoid potential signal jamming: confusion might occur if all dolphins traveling together in a group were actively echolocating on a particular target. This suggests that eavesdropping might be something dolphins actively practice. We know that dolphins can listen to other dolphin echoes. Researchers at The Living Seas, Epcot Center, showed that a bottlenose dolphin trained to listen only to the clicks of an actively echolocating dolphin could discriminate targets.18 This observation provides evidence that dolphins can detect and interpret the echoes of another dolphin’s sonar. But we still do not definitely know if wild dolphins have these abilities.

These results raise an interesting question about the etiquette of echolocation use and how individual dolphins within a group know when it is proper to echo-locate and when it is not. One of Kathleen’s doctoral students, Justin Gregg, from Trinity College Dublin, Ireland, is investigating this topic in his research of the bottlenose dolphins at Mikura Island. Justin is using data collected with Kathleen’s mobile video/acoustic system and echolocation click detector (more about these instruments later) to see whether these wild dolphins echoically eavesdrop on one another; he has created a three-dimensional method for measuring the angle between the heads of two dolphins as they appear on video, swimming next to each other and toward the mobile video/acoustic system.19 As we learn more about dolphin social behavior and communication, we are able to answer research questions and refine them in order to direct future study. We are beginning to see that wild dolphins do indeed use their clicks for social reasons and not just for foraging or short-range navigation. Each nugget of information that we glean from our data and results gives us a better understanding of the many ways dolphins communicate, as well as how these methods might be used alone or in concert.

Many dolphin whistles are within our hearing range of about 2 kHz to 20 kHz and last from milliseconds to a few seconds. These sounds can have a rich harmonic content (think of a symphony) that extends into the ultrasonic range of frequencies—three to four times higher than the range of human hearing. Musicians refer to the perceived whistle frequency as the pitch; the duration is the length the whistle occurs. Graphing these two bits of information provides the picture, or contour pattern, of the whistle on a spectrogram. When we examine these whistles as spectrograms, we see that they vary greatly in contour and shape, representing changes in pitch over time from simple up or down sweeps to warbles, U-loops, and inverted U-loops. Whistles with harmonics sound more “full” to the human ear, and perhaps to the dolphin ear, and are represented by multiple lines above the main whistle contour. Conversely, clicks on a spectrogram are represented more by vertical parallel lines. The main reason for this picture difference is how they are modulated: whistles are frequency-modulated pure tones, whereas clicks are amplitude-modulated and express energy across multiple frequencies. Click or pulsed sounds with high repetition rates such as burst-pulse whines or squawks can resemble whistle contour patterns on a spectrogram. Burst-pulses consist of hundreds, even thousands, of clicks per second, and the resulting contour can appear blended. The spectrogram is the best method for visual representation of dolphin sounds that we study.

Whistles function for communication, but as we have discussed, not all dolphin species whistle. A few species, such as Hector’s dolphin and Commerson’s dolphin, do not. We do not know why some whistle and others don’t. The characteristic of whistling seems to appear in species with specific ecological or social conditions, though this assertion is not all-inclusive. For instance, all whistling species are highly gregarious. Most nonwhistling species share a characteristic of low gregariousness, but Hector’s dolphins live in very social groups and do not whistle.20

Because whistles have a relatively lower frequency than pulsed sounds, they travel farther in water. Low-frequency sounds have a longer wavelength than higher-pitched sounds, which allows them to travel farther—their wave shapes can move around objects rather than get blocked or bounced back by these obstacles. Think of a length of rope: two people hold the ends and move their ends slowly up and down. This would create long wavelengths. Conversely, if they moved their arms up and down swiftly, they would create short wavelengths. The rope and waves represent the sounds that we hear: long versus short and the continuum between these extremes.

For further illustration, consider these nonaquatic examples: elephants and birds. Elephants, as we have seen, use low-frequency sounds well below human hearing to communicate over long distances. Atmospheric conditions certainly affect sound transmission, generally speaking, low frequency equals longer wavelength, which equals greater range over which to communicate. Most birds, in contrast, produce high-pitched sounds. Think of the bird songs you hear each morning and note how their songs do not carry very far because of their high frequency.

Dolphins produce a variety of sounds, all represented on this spectrogram.

Dolphins that whistle can produce whistles and clicks simultaneously. Whistles might provide a potential vehicle for maintaining contact and coordination among group members while searching for food with echolocation. Whistles and sonar do not overlap in fundamental frequency, thus minimizing potential masking effects or miscommunication. Species, regional, or individual specificity in whistles facilitates identification of schoolmates or familiar associates, aids in the assembly of dispersed animals, and helps maintain coordination, spacing, and movements of individuals in rapidly swimming, communally foraging herds.

A wealth of data has been gathered on dolphin vocalizations and their concurrent nonvocal behavior. Hawaiian spinner dolphins, bottlenose dolphins, and pilot whales make a variety of sounds that change in type and rate with behavioral activities.21 For these species, the highest number and variety of sounds, including whistles, screams, and barks, are created during social activities. In contrast, when resting, dolphins can be nearly silent. Toni has found that captive bottlenose dolphins whistle more when swimmers are in the water than when they are not.22 These observations seem intuitively correct—specifically that signal exchange is higher and more complex when dolphins are more interactive, just as a room full of socializing teenagers sometimes threatens to break the decibel barrier with whooping and hollering.

Although data on rates and occurrences of vocalizations are valuable, we must identify the individuals making specific sounds as well as examine the behavior that accompanies the sounds to develop a complete picture of dolphin communication. When observing how dolphins behave at close range, identifying which individual initiates contact behavior (touching) and which receives it is relatively straightforward. The same can be said of postures or other visual cues. As we have seen, however, dolphins do not have to be within sight of one another to communicate. This, coupled with the facts that sound travels four and a half times faster underwater than in air, that dolphins usually exhibit no external sign that they are producing sounds, and that humans are designed to localize sounds in air but not water, makes it hard for humans to assign initiator and receiver roles in dolphins in the wild. Belugas are unusual in this regard because we can often see who is vocalizing —the undulations of the melon are almost as visual as a person’s moving lips. Belugas are also the only odontocetes that can move their neck to orient their head in different directions, which might aid in determining who is vocalizing. Other odontocetes cannot move their necks freely.

The mobile video /acoustic system (MVA) is the tool that Kathleen uses to record and document dolphin signal exchange. The MVA captures stereo audio with a video record of the behaviors.

The advent of new technologies and a melding of talents among biologists and engineers have paved the way for novel methods for recording dolphin behavior and sounds simultaneously underwater. In 1992, with advice from my dad, Pete (an electrical engineer), and graduate adviser, Bernd Würsig, I (Kathleen) designed and built a mobile video/acoustic system (MVA) to record dolphin behavior and their sounds concurrently, which I have been using ever since as a tool to study dolphin communication. The MVA, or “array,” as I affectionately call it, has two underwater microphones (hydrophones) spaced at roughly four and a half times the distance between my ears. The hydrophones are located at the ends of a bar attached to the housing, where they are plugged into a stereo video camera.23 In 1997, after several years of underwater observations and much already learned about dolphin behavior and interaction, I added a third hydrophone, a digital audio recorder, and a circuit board to capture and record echolocation from wild dolphins as they approached the MVA.24 This unit was nicknamed the ECD, or echolocation click detector, because it allowed us to record click trains from individual free-ranging dolphins that we were observing as they swam toward the camera. These two devices were, and still are, innovative even with only two or three hydrophones. It was not until 2005 that modifications to this original design were proposed and made possible because of more recent technological advances, such as the creation of really tiny hard drives and even smaller cameras and batteries.25

My array is one of the few tools available to us to study free-ranging dolphin communication from underwater. Individuals in a group may consistently surface to breathe in a reliable pattern, but when socializing underwater they zigzag around one another in what appears to human eyes as aquatic “tag.” Each season and every new recording and observation provide fresh insights into what and how dolphins are signaling to one another. Observing dolphins that are habituated to swimmers in relatively clear water facilitates the study of dolphin communication: more often than not, we can identify the signals used, the sender, and the receiver by using the MVA.

Another tool of our trade is in our methodology for recognizing and identifying individual dolphins. We use naturally occurring scars and marks to recognize each dolphin or beluga reliably in each group that we study. Most dolphins are easily identified by the notches and scars in their dorsal fins. When studying them underwater, we gain access to views of the entire dolphin body and can document marks, pigment differences, and scars anywhere on their form. We assign each dolphin a name and/or number. Standard convention in the scientific study of animals dictates that we maintain objective and impersonal views of our subjects to prevent us from anthropomorphizing them. In contrast to this system, Jane Goodall named the chimpanzees at Gombe, Tanzania, as an acknowledgment that the chimps were individuals with character traits and “personalities”—this helped people (scientists included) to traverse the chimp-human border. Since Goodall’s studies, the assignment of names to nonhuman subjects has become more accepted.

Several attempts have been made to inventory the whistle repertoire of wild and captive dolphins. The size of a repertoire, for a species or an individual, including both whistles and pulsed sounds, is probably limited to fewer than forty discrete types.26 It is possible that whistles are graded, rather than discrete, signals—that is, these signals sort of fade into one another, having subtle differences in meaning rather than being distinct sounds. Although this is not a vocabulary like we would find in a dictionary, we are beginning to understand how some dolphin sounds might correlate to certain behaviors. We are learning about the “how” and the “what” behind dolphin communication. Consider again the importance of touch for communication. For instance, placement of the pectoral fin by one dolphin to the side between the dorsal fin and the flukes of a second dolphin is termed contact position.27 Researchers in Australia have described this behavior as “bonding.”28 In most reported cases, the action is a request made by the first dolphin. In another example, pairs and triplets of dolphins engage in ganglike fights, “squaring off” with loud sounds, bubble emissions, and lots of posturing. After about five to six minutes, the fighting stops, and members of each pair or trio swim quietly in parallel in layered contact position.29 While exchanging pectoral fin touches, the dolphins are nearly silent or whistling mildly. During the fight episode, between flipper touches and affiliative exchanges, the dolphins are noisy and overt in their actions. Therefore, “contact position” likely sends two messages— depending on the receiver. To partners: “We’re still on the same team, right?” To opponents: “You still have to take on our team as a whole.” These tactile messages are reinforced or solidified by the accompanying acoustics, postures, and gestures.

Dolphins place a pectoral fin on the side of another dolphin when asking for assistance or other action. We see this often between dolphins when they fight in groups. During breaks in fighting, dolphins within each gang place their flippers to the sides of their peers. This signal lets their partners know they are still a team and advertises to their opponents that their team is still tight.

A clearer concept of the message behind the behavior of contact position as a request was strongly emphasized during my (Kathleen’s) fieldwork in July 1994. It was dusk, with light too low for good video recordings and the sea just shy of turbulent (think of a washing machine on the gentle cycle). I was in the water with another woman and two juvenile female dolphins, Topnotch (ID#3) and Doubledot (ID#39). A glance at the boat, which was a good hundred yards (about 100 m) away against the current, told me it was time to say good night to our friends and battle the waves back to the boat. I signaled to my friend. We watched the dolphins swim out of view and then started our swim to the boat. After about a minute, both Topnotch and Doubledot swam back to us: Topnotch paralleled me, Doubledot my friend. As we swam, Topnotch let me place the back of my hand against her right flank—contact position. After we reached the boat, both dolphins swam back toward other swimmers finishing their last swim of the day. Topnotch then swam back to me, pressed her entire right side into my body, rubbed her belly into my belly, and then moved off to Doubledot! Had I asked her for the rub and contact? Or had I asked for some other signal? In that instant, more than any other in my life, I wished I had Dr. Doolittle’s ability to talk to the animals. Maybe, with more observations of behavior, we will eventually be able to understand and converse, in some form, with the animals.

Occasionally the observer becomes the participant, particularly when blinds (used to conceal the observer from land animals) are not an option for underwater dolphin research. When the animals being observed detect the researcher, challenges (or opportunities) arise. If the animals do not flee, the researcher, instead of being ignored, may become the target of attention. The observer may become an active participant in interspecies communication or may choose to be an unresponsive observer. Because dolphins are often so gregarious toward people, it is not uncommon for this to happen.

I (Toni) observed a free-ranging “friendly” beluga whale in Nova Scotia that had been interacting with swimmers and boaters in the area for several years. It was my first time in the water with this whale, and my intention was to make myself as uninteresting as possible to her so that I could study her underwater behavior as an objective observer. The whale, however, had a different agenda. It seemed that the less responsive I was to her solicitations for attention, the more persistent she became in engaging me to interact with her. After repeatedly rubbing her body along my hands, which I kept relaxed at my sides despite the temptation to stroke her, she reoriented her body at the surface so that we were both floating, head to head. She pressed her bulbous melon into my forehead ever so gently and just held it there, almost motionless.

Toni and Wilma share a quiet moment together.

Although I did not understand the specific meaning of this behavior, it seemed clear that she wanted me to interact with her rather than simply observe her. . . so much that she took matters into her own hands. I saw this behavior again with a different “friendly” beluga when he gently pressed and held his melon against a diver’s head. I have been unable to find anyone who has observed this behavior occurring between belugas. Perhaps the rare opportunities for close, in-water interaction with these animals reveal aspects of their communication that we would be unlikely to witness by observing them from afar. In this way, and when conducted responsibly, close observation may provide an invaluable window into the rich communicative expressions of dolphins.

Individuals within species direct behaviors to one another that are generally understood and interpreted correctly by other members of their species (or culture, when applicable)—and the responses they receive are somewhat predictable, too.30 As a result, members of a species typically know what they can expect from one another. Effective communication can certainly be more challenging between individuals of different species, however. Signals that have become specialized through evolutionary processes to communicate with peers are unlikely to be highly effective for communication across species.31 And yet, because members of different taxonomic groups are often in contact, communication does occur between individuals of different species.32

Over time, individuals, whether dolphins or other animals, may learn the meanings of signals exhibited by members of another species, and the two species may even develop mutually understood signs.33 Examples of this are replete in human interactions with domestic animals and in animal training. Naturalists and researchers also attempt to learn and exhibit the signals of other species in efforts to interact with them. This strategy has been used with dolphins by the pioneering cetologist Kenneth Norris and others, with chimpanzees by Jane Goodall, and with captive and free-ranging gorillas by Brenda Patterson and Diane Fossey, respectively, among others.34

Cetaceans of different species interact with one another more often than do many other taxonomic groups. Spotted dolphins in The Bahamas frequently intermingle with bottlenose dolphins.35 Common and dusky dolphins travel together off Argentina as well as in New Zealand waters.36 Mixed species aggregations are also regularly seen in the eastern tropical Pacific.

Dolphins that frequently interact with humans may have learned how to communicate on some level with people, especially individuals they interact with repeatedly. One example of this communication may be the dolphins’ mimicry of human postures and vocalizations, as exhibited by free-ranging Atlantic spotted dolphins, lone sociable bottlenose dolphins, solitary free-ranging beluga whales, and captive dolphins.37 Dolphins who are around people in swim programs often circle or somersault around and in copy of human actions. Interspecies communication may also occur on a different level between captive dolphins and their trainers during reinforcement training.38 Dolphins learn the meaning of their trainers’ signals and behave according to the information inherent in the signal. Conversely, trainers often learn the significance of “intra-specific social signals” that dolphins may direct toward the trainer.39

Communication may also occur through play behavior, which can serve as an important mechanism in the development of communicative skills.40 For this reason, play between dolphins and humans may provide the motivation and basis for the development of mutually understood signals necessary for interspecies communication. Although play between species is not common, this may be due primarily to the relative infrequency of prolonged social interaction across species.41 Of those species that do interact socially with others (think of domestic dogs and humans), play is common. Researchers suggest that play is a component of social interactions between free-ranging dolphins and swimmers who frequently engage with one another.42 Dolphin behaviors such as allowing humans to ride or be towed and playing keep-away with seaweed and other objects are often documented.

So why study communicative behavior in dolphins? Obviously, it’s a fascinating subject with many implications. But is there a greater purpose? Absolutely. Increased public education about dolphin communication and behavior may contribute to greater public protection of dolphins and their habitats. More directly, dolphin communication and expression convey important information about their internal states and subjective experiences. Knowledge of their behavior allows us to glimpse into their psychological and physiological condition.43 And this information in turn enables people (including scientists, fishers, boaters, swimmers, veterinarians, and natural resource managers) to better manage and care for individuals as well as populations. For instance, what we have learned about dolphin behaviors associated with stress has been instrumental in setting policies for the tuna fishing industry, which has an incidental impact on dolphins.

By eavesdropping on dolphins, we find that the ways in which dolphins communicate with each other—and even with us—are incredibly sophisticated and complex, even by human standards. Even with vast differences between humans and dolphins in physiology, sensory systems, and habitat, the language of dolphins is unfolding before us as we spend more time beneath the surface.