Chapter 16

Leading in Times of Change

IN THIS CHAPTER

Seeing how your brain processes change

Understanding how to lead when change is the norm

Checking out different models of change leadership

Discovering mindful strategies for leading change

Change is nothing new – in fact, it’s the only constant in life. What is new is the pace of change. Long-established leadership models for leading change are based on the assumption that each change has a clearly defined start and end point. What companies are facing now is ongoing ‘bumpy change’ with little or no time to adjust and adapt before the next wave of change hits them.

This chapter explores new ways of leading in a more mindful manner in times of change that will equip you to manage this constant ongoing change.

Understanding Change from Your Brain’s Perspective

Every second of the day, your brain is hard at work keeping you alive and repairing and maintaining your body. Setting this aside, your brain’s primary function is to maximise reward while minimising threat. To do this, your brain pays more attention to things it decides are potentially harmful. This stems back to ancient times when humans faced regular life-and-death situations. If we failed to see the ‘tiger’ in the bushes we would be dead.

The good things in life (shelter, food, friendship, and a sense of achievement) are good, and in most cases, they’re unlikely to harm or kill you, so the brain tends not to linger on them. Instead, the brain focuses on the next goal, such as delivering a project on time and on budget, buying a new car, or getting a promotion. The brain initially treats anything that might get in the way of you achieving this goal or reward as a threat and pays it a lot of attention in an attempt to help remain safe and stay on track to achieve your goal.

Under normal circumstances when you’re working in a calm and level-headed way, your brain learns by experience not to panic or activate your threat system when you encounter challenges along the way to achieving your goals. You engage your higher brain circuitry to plan, prioritise, make decisions and think of new and innovative ways of working. Your primitive brain makes good use of tried and tested ways of working that have served you well in the past for the more routine tasks at work.

Change creates uncertainty. The human brain hates uncertainty. In an effort to reduce uncertainty, your brain seeks information. The problem is that often this information is unavailable until later on in the change process. In a bid to create certainty where none exists, your brain starts to construct stories about what’s happening and what’s likely to happen. Due to the negativity bias, these are often catastrophic stories as the brain fills the information gap with the worst scenarios possible. It then treats these stories as facts and uses them as the basis for decisions and actions.

Think of a sudden or unexpected change that you encountered at home or work and answer these questions:

- What happened initially?

- How did you respond initially?

- Were you aware of any initial thoughts or emotions in response to the change?

- Did you make any assumptions of what was happening or was going to happen? If so, what were they?

- What happened in the end?

When faced with a sudden or unexpected change, you can easily jump to conclusions or think the worst. You may initially experience what psychologist Daniel Goleman calls an ‘amygdala hijack’ – an immediate, overwhelming emotional response followed later by a recognition that the response was inappropriate. This is because strong emotional information travels directly from the thalamus to the amygdala without engaging the higher ‘thinking brain’ regions. This causes a strong emotional response that precedes more rational thought.

Mindful leaders can recognise and then accept this human response to threatening stimulus. Doing so helps them to bring conscious awareness to what’s going on and reduces the likelihood of being sucked into negative thought spirals that trigger strong emotions and can result in inappropriate behaviours.

Being a mindful leader won’t stop you from experiencing the pain and suffering that change can bring, but it will help you to reduce its impact and put your higher thinking brain back in the driving seat more quickly. It will also help you to take better care of yourself so you can be the best leader you can be even when under immense pressure.

Mindful leaders are more aware of what’s going on inside themselves and around them moment by moment. This enables them to observe the impact of the change on their peers and team, helping them to decide what’s most needed at any moment in time.

Becoming a more mindful leader doesn’t suddenly turn you into a superhero. As a leader, you’re still a human and are still likely to experience the same human responses to change as others around you. Mindful leadership is about being human, honest and authentic. At times, sharing with your colleagues or team that you feel scared or insecure may be appropriate. At other times, you may need to be a statesman, saying and doing the right thing to create some forward momentum. In this instance, it’s still important to acknowledge and accept your own fears and insecurities and cut yourself some slack. Doing so is a sign of strength, not weakness, as it helps you to maintain an optimum state of mind that enables you to be the best you can be (see the model in Chapter 1).

Becoming a more mindful leader doesn’t suddenly turn you into a superhero. As a leader, you’re still a human and are still likely to experience the same human responses to change as others around you. Mindful leadership is about being human, honest and authentic. At times, sharing with your colleagues or team that you feel scared or insecure may be appropriate. At other times, you may need to be a statesman, saying and doing the right thing to create some forward momentum. In this instance, it’s still important to acknowledge and accept your own fears and insecurities and cut yourself some slack. Doing so is a sign of strength, not weakness, as it helps you to maintain an optimum state of mind that enables you to be the best you can be (see the model in Chapter 1).

Leading When Change Is the Norm

Change is no longer a short break from ‘business as usual’ – it’s now the norm. We live and work in a world that’s volatile, uncertain, complex and often ambiguous (VUCA). In a VUCA world, leaders need to adapt to and stimulate continuous organisational change.

Older models of change leadership are often top-down strategies for gaining buy-in and overcoming resistance to discrete initiatives. These models are designed with the aim to control change. They often fail to create shared, long-term ownership and engagement. Neither do they lead to a heightened readiness and flexibility in the face of continuous, emergent change – a symptom of the VUCA world. Traditional change models often result in employee cynicism and fear, reducing productivity and creativity and making an organisation even less resilient.

Learning is a process of change, and change is a process of learning. In order to manage change, you need apply a structured process and set of tools for leading the human aspects of change in order to achieve a desired goal. The next few pages explore your role in leading change, suggesting some new ways to consider, plan and lead the process.

Managing change or leading change?

Although you may hold a leadership role, it’s important to ask yourself whether you’re really leading change or simply trying to manage it. Change management is facilitating the change process, whereas change leadership empowers action that allows change to take off.

Change leaders work collaboratively and seek to inspire. Being a change leader isn’t simply a case of making change initiatives efficient; change leaders need to be able to take risks to find new ways of working instead of merely seeking to control and contain the change. Change leadership initiates change on a large scale instead of making small changes or adopting a silo mentality

Good change leaders recognise the need for change and respond to it quickly, leaving their managers to create order, set timelines and manage budgets. They innovate and set engaging visions, leaving managers to integrate the visions so they become ‘the way we do things round here’. Change leaders empower those around them to create change for themselves instead of simply encouraging them to adapt.

Change leadership isn’t about working through a defined change process by using some tools and techniques while remaining organised and reporting on your project plan. Change leadership requires leadership skills. Leaders need to have an in-depth knowledge of their company and its customers and competitors, communicate effectively, taking into account individual and collective responses to change, and encourage creativity and innovation.

Observing the change continuum

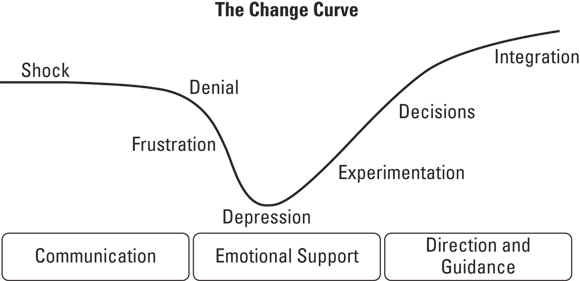

Are you familiar with the change curve? The change curve, shown in Figure 16-1, is based on a model originally developed in the 1960s by Elisabeth Kubler-Ross to explain the grieving process.

The change curve model explains the emotional roller-coaster that people go through when experiencing a sudden or unexpected change. People pass through the different stages on the curve at different speeds. At the early stages, people need you to communicate with them as much as possible. In the middle stages, you need to be especially mindfully aware of people’s need for emotional support, creating an environment that allows them to get this from their workmates, family or you. At the later stages, try to get your team as involved as possible in creating their new future, being there to direct and guide them towards it.

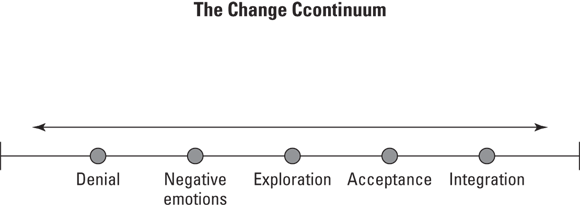

With today’s bumpy change, I like to think of the change curve as more of a change continuum (see Figure 16-2). As each change ‘bump’ is encountered, people may remain static, move backwards or forwards on the continuum, with no distinct start or end point, as one change may ‘hit’ before another change is fully embedded.

Using this model, mindful leaders need to constantly assess at what point on the continuum individuals and the majority of the team are, and flex their leadership style to help them to progress more rapidly towards a productive working state. Instead of thinking of each change as an individual entity, by accepting and embracing the fact that change is the norm, mindful leaders suffer less change fatigue, and their team becomes more accepting of the constantly changing nature of their work.

Exploring Models of Change Leadership

Although many companies claim to actively manage change, a recent poll indicated that 60 per cent of all companies use no specific change model to manage change. Of those who did, 20 per cent used Kotter’s model and 17 per cent used the Prosci model. In the next few pages, we explore a few approaches to leading change, some well known, others less known, but worthy of consideration. You can then mindfully select the right approach for your organisation, or design one yourself.

Kotter’s model of change leadership

In 1996, John Kotter introduced an eight-step transformation model based on analysis from 100 different organisations going through change, as outlined here:

- Step 1: Establish a sense of urgency.

- Step 2: Form a powerful guiding coalition.

- Step 3: Develop a vision and strategy.

- Step 4: Communicate the vision.

- Step 5: Remove obstacles and empower action.

- Step 6: Plan and create short-term wins.

- Step 7: Consolidate gains.

- Step 8: Anchor in the culture.

Although the model appears linear, it’s best to think of it as a continuous cycle that maintains momentum for the desired change.

Prochaska and DiClemente’s stages of change model

Unlike other change models, this model focuses on the human dimension of change. Change is a process that unfolds over time. It is a process that involves you passing through a number of stages, which may result in a change in your behaviour. The model defines these as precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action and maintenance

Applied to organisational change it involves the leaders making a number of covert and overt moves to help employees adapt their behaviour and mindsets in the face of change.

The process starts with the leader making it clear to employees the things that need to done differently in the future – for example, using new technology appropriately, working collaboratively in a team, performing with total quality improvement guidelines.

At the precontemplation stage, individuals are not ready to act. They may feel demoralised from having failed to make changes in the past. They may not even be considering change. At this stage, leaders need to raise consciousness as to why it is important to make the behavioural changes and to raise the pros of doing so. They should acknowledge their lack of readiness but find subtle ways to encourage them to re-evaluation of current behaviour. A good strategy might be explaining and personalising the risk they face by not changing.

At the contemplation stage, individuals begin to think about or get ready to act or do things differently. They may still be ambivalent about the change or ‘sitting on the fence’. At this stage, leaders need to reduce the ‘cons’ of doing the new behaviour and inspire the employee to work towards what the organisation can become with the move to action. They might consider getting the teams together to re-evaluate their group image through group activities, or identify and promote new, positive outcome expectations

At the preparation stage, individuals are ready to act. Some start to test the water and try to start changing their behaviour. At this stage, leaders need to prepare and encourage employees to make a commitment to perform the new behaviour, to take small steps, and to learn the behaviours that are needed to be in action. The leader needs to identify and promote new, positive outcome expectations in the individual and encourage taking small initial steps.

At the action stage, employees are performing the new behaviours, but the change is not yet embedded. Stimulus control is important, as well as rewards, helping guiding relationships, and using substitutes (substituting the new behaviour for the old behaviour). At this stage, people start to make deliberate actions moving towards the new desired behaviours. Leaders need to be cautious at this stage as it’s easy for staff to slip back to old ways of doing things. They need to help the team to establish new social and cultural norms, overcome barriers and obstacles and deal effectively with feelings of loss and frustration.

Maintanance is gained after six months of repeating the new behaviour. At the maintenance stage, it’s important to stay on track. Ongoing, active work is needed to maintain changes in behaviour and prevent a slip back to old ways of working or thinking. Stimulus control, rewards and helping relationships continue to be important. As the individual’s confidence increases, the danger of returning back to old ways of working diminishes. At this stage, the leader needs to plan in follow-up support, and provide rewards (praise, recognition or financial) to continue with the new behaviour.

Prosci's ADKAR Model

Prosci developed the ADKAR model in 1998 based on research gathered from more than 300 companies who were undergoing major change projects. ADKAR is a goals-oriented change management model that encourages change managers and their teams to focus their activities around specific desired business results. The benefits and limitations of this model are as follows:

- Benefits: It focuses on the business process element of change in addition to the individuals involved in the change process.

- Limitations: It misses out the role of leadership in the process, which may lead to a lack of clarity and sense of direction.

Although many change management projects focus on the steps necessary for organisational change, the Prosci ADKAR model focuses on five actions and outcomes necessary for successful individual change and therefore successful organisational change. For change to be effective, individuals need the following:

- Awareness of the need for change

- Desire to participate and support the change

- Knowledge on how to change

- Ability to implement required skills and behaviours

- Reinforcement to sustain the change

Knowledge and practice of mindfulness, together with some basic knowledge of how the brain works on the part of both the leader and employees, make this model even more effective. In the words of Jon Kabat-Zinn, founder of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), ‘You can’t stop the waves, but you can learn to surf’.

Practicing Mindful Strategies for Leading Change

When leading change, it’s easy to focus on numbers and statistics. This sometimes overshadows the human aspects of change. The human need for safety, certainty and control is more likely to derail a carefully planned change project than a failure to accurately predict budgets or future profits.

Here are three mindful strategies for leading change:

- Letting go of the illusion of control

- Becoming more emotionally intelligent

- Remaining rooted in the present moment

We discuss these strategies in detail in the following sections.

Letting go of the illusion of control

Irrespective of the position, power and influence you may hold, you never really have true control over your life, no matter how wealthy or educated you may become. Leaders commonly overestimate their ability to control or influence what’s happening around them.

Instead of seeking to have more control in your life, it’s often better to strive for more resilience. Merriam-Webster defines resilience as ‘an ability to recover from or adjust easily to misfortune or change’. Times are always changing, and you can make yourself miserable by trying to cling to the past or reject your current circumstances. Mindful leaders learn to quickly identify the things they can’t influence or change and then actively choose to accept them instead. This is particularly useful in times of change. Doing so allows you to focus your energy, time and attention on things that you can control or influence for the better.

Mindful leaders assess all the information at hand and make the decision about what to do now that will have the best likelihood of a desired outcome in the future. After you make the decision, you can use feedback to adjust and adapt as needs dictate. As to what you may do in the future or unpleasant outcomes that can happen, those are only relevant to the extent that it influences what you need to do now. If you can do nothing now to change potential future outcomes, then there is no point in thinking about them.

Becoming more emotionally intelligent

When leading through change, managing your physical assets is never the issue – the human response to change is. Leading change is about leading people, and change can be an emotive subject, so emotional intelligence (EQ) is key. A number of researchers have identified a positive relationship between EQ and mindfulness. Practicing mindfulness helps you to develop your emotional intelligence in three ways:

-

Mindfulness helps you to identify and understand your emotions better. Practicing mindfulness helps you to observe your emotions, moment by moment. This conscious awareness creates a small gap between the stimulus and your response. This gap or brief ‘thinking space’ allows you to choose how to respond, based on an assessment of facts as opposed to emotions like fear or anger.

People who practice mindfulness tend to have a higher awareness of their emotional state, noticing as emotions come, go and change. Other research concludes that the more mindful you become, the clearer your awareness is of feelings, resulting in lower distraction.

- Mindfulness helps you to develop the ability to detect and understand the emotions of others. A research study concluded that being mindful allows you to focus your attention better on how other people around you are feeling and helps you to notice and decipher emotional cues of others more accurately. It can also improve your empathy. Another study demonstrated that those who attend mindfulness training have more empathy for themselves and others.

- Mindfulness helps you to enhance the ability of individuals to regulate and control their emotions. Researchers discovered that people with a higher level of mindfulness tended to recover more quickly from emotional distress compared with those with a lower level of mindfulness – something that could give you the edge in times of change.

Mindfulness can help you to use your emotions more effectively. Mindfully observing your emotions while suspending judgment allows you to adopt an emotional state, which helps you to focus on and perform a task better and avoid performing a task that you can’t perform well when certain emotions are present.

Mindful leaders are aware of their emotional state and over time develop sufficient EQ to select the optimum emotional state to get a task done well. Being in a positive mood is important for tasks that require creativity, integrative thinking, and deductive reasoning, but being in a negative mood tends to make people become more effective in tasks that require attention to detail, detection of errors and problems, and careful information processing.

Emotions aren’t necessarily a bad thing, but they can have a major impact at inappropriate moments. When emotions become overwhelming, try the RAIN model developed by mindfulness teacher Tara Brach. You can use this model at work or home to help manage your feelings in a more mindful way.

Stop and focus on the present moment sensations of breathing.

Stop and focus on the present moment sensations of breathing.

- R – Recognize the emotion you’re feeling.

- A – Accept the experience you’re having.

- I – Investigate. Become curious about your experience.

- N – Non-identification. See the emotion as passing events, without the need for further response.

Remaining rooted in the present moment

Practicing mindfulness helps you to develop the ability to remain rooted in the present moment when you need to. This helps you avoid getting caught up with overanalysis of past mistakes and wild predictions of the future. It allows you to assess things as they are in the moment with clarity and decisiveness.

As a mindful leader, you can do a number of things to help encourage others to remain rooted in the present, including the following:

- Ban laptops, mobile phones and other devices during meetings. Many Silicon Valley workplaces already do this.

- Encourage single tasking. Stanford researcher Clifford Nass discovered that multitaskers get much less done because they use their brains less effectively.

- Encourage others to apply the 20-minute rule. Instead of switching tasks from minute to minute, dedicate a 20-minute chunk of time to a single task, and then switch to the next one.

- Encourage others to take breaks. Productivity diminishes if you work all the time. Taking breaks is good for you, not to mention essential to rebuilding your attention span.

Becoming a more mindful leader doesn’t suddenly turn you into a superhero. As a leader, you’re still a human and are still likely to experience the same human responses to change as others around you. Mindful leadership is about being human, honest and authentic. At times, sharing with your colleagues or team that you feel scared or insecure may be appropriate. At other times, you may need to be a statesman, saying and doing the right thing to create some forward momentum. In this instance, it’s still important to acknowledge and accept your own fears and insecurities and cut yourself some slack. Doing so is a sign of strength, not weakness, as it helps you to maintain an optimum state of mind that enables you to be the best you can be (see the model in

Becoming a more mindful leader doesn’t suddenly turn you into a superhero. As a leader, you’re still a human and are still likely to experience the same human responses to change as others around you. Mindful leadership is about being human, honest and authentic. At times, sharing with your colleagues or team that you feel scared or insecure may be appropriate. At other times, you may need to be a statesman, saying and doing the right thing to create some forward momentum. In this instance, it’s still important to acknowledge and accept your own fears and insecurities and cut yourself some slack. Doing so is a sign of strength, not weakness, as it helps you to maintain an optimum state of mind that enables you to be the best you can be (see the model in