The Road from the Ends of the Earth

For many centuries, the Celts were a mystery to their neighbours. In the sixth century BC, the Greeks had heard from intrepid merchants following the tin routes or from sailors blown off course of a people called the Keltoi, who lived somewhere along the northern shores of the Mediterranean. In the early fifth century, when the historian Herodotus tried to shine a light on this distant world, he was like a traveller on a starless night holding up a candle to the landscape. Of the Celts, he had been told the following: they live in the land where the Danube has its source near a city called Pyrene, and their country lies to the west of the Pillars of Hercules, on the borders of the Cynesians, ‘who dwell at the extreme west of Europe’. This was either fantastically inaccurate (the supposed homelands are nearly two thousand kilometres apart) or an over-condensed version of an amazingly accurate source. Celtic tribes are known to have existed at that time both in the Upper Danube region and in south-western Iberia.

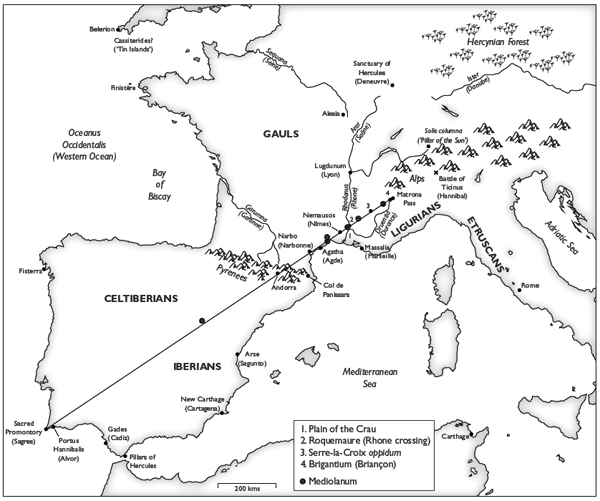

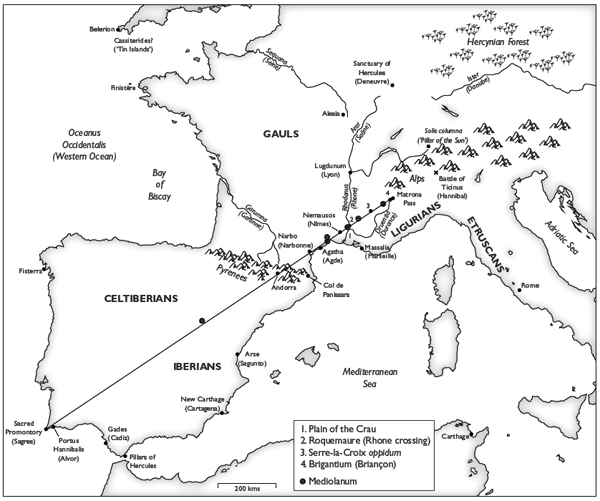

The Pyrenees – confused by Herodotus with a fictitious city called Pyrene – lie almost exactly halfway between the two. They form a great barrier across the western European isthmus, from the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea, dividing France from Spain. Most of the trans-Pyrenean traffic crossed at either end, where the mountains tumble down to the sea, but the central range was surprisingly porous. In the early Middle Ages, the road that leads to the principality of Andorra was used by smugglers, migrant labourers and pilgrims bound for the shrine at Santiago de Compostela. The snowy passes of the Andorran Pyrenees lie on the watershed line, from which the rivers flow either west to the Atlantic or east to the Mediterranean. In the days of the ancient Celts, this was the home of a tribe called the Andosini, who entered history when they were defeated by Hannibal in 218 BC during his long march from Spain to Italy. No one knows for certain how the Carthaginian general came to encounter such a remote tribe, but ancient history sometimes hinges on a place that seems desolate beyond significance.

1. The Road from the Ends of the Earth

The Celts’ own stories of their origins were told over an area so vast that the sun spent an hour and a half each day bringing the dawn to it. Because the Celts were a group of cultures, not a race, they spread rapidly from central Europe, by influence and intermarriage as much as by invasion, until the Celtic world stretched from the islands of the Pritani in the northern sea to the great plains east of the Hercynian Forest, which even the speediest merchant did not expect to cross in under sixty days. As a result, although the tales were told in dialects of the same language, they took many different forms, like trees of the same species rooted in different soils and climates.

One tale in particular was considered pre-eminent and true, since it described what appeared to be a real journey made by a founding father of the Celts. It survived in various fragmented forms; some of the incidents became detached from their original context or were too strange to be part of a coherent narrative; yet they were held together by the geography of half a continent. The journey began at the extreme western tip of Europe – the Sacred Promontory, where a temple to Hercules stood above the roaring sea in a place so holy that no one was allowed to spend the night there. But it was in the mountains between the two seas that the hero entered the country known as Gaul. And since Gaul is the heartland of the first part of this adventure, this is where the story of Middle Earth begins.*

With the mists of the Western Ocean draped over the pine forests, it would have been easy to imagine the scene: the smoke climbing up through the trees, the crackle of branches, and the fire, as red as a lion’s mouth. Cattle were stumbling down the riverbeds to the hot plains below. The man knew the route they would take. From the ends of the earth, where the sun and the souls of the dead plunge into the sea, he had followed rather than driven them, so that it was not entirely true to say that he had stolen the herd. He acted out of desires that were foreign to his mind but not his body. It was in the country of the Bebruces, at the time of year when the sun rises and sets in the northern sky. The daughter of King Bebryx had served him bread, meat and beer in the great wooden hall, and when the sun had returned to the lower world she had taken him to her bed, and he had filled her with the seed of a god’s son until the great hall shook and the walls of her chamber were beyond repair.

He had left the hall like a god or a thief. But the part of him that was human was stung by his act of abandonment. He thought of the creature like a snake that was growing inside her; he thought of her shame and of a father’s rage. He had stopped where the cork oaks and the olives begin. He strode back up into the green, dark mountains, towards the ridge he had dented and levelled with his feet. Her white limbs lay scattered on the ground as though they had lain together on the pine needles and she had been dismembered by the force of his love. He gathered up the remains of the wolves’ feast. Her blood, and the blood of a god’s strange grandchild, burned his hands. He thundered her name to the skies that he had once held aloft – the Greek-named daughter of a Celtic king. Her name meant ‘fire’, ‘a gem’, or the gold ‘grain’ of the harvest. He felled a forest, then another. Rivers that had yet to be named began to flow from the bare mountain tops. He built a pyre that the midday sun would light. The smoke would be seen from the Ocean, where sailors hugged the coast in boats of skin; then the wind would carry it across the isthmus to the safe, thronged harbours of the Middle Sea, and even that blazing range of peaks would be unworthy of his Pyrenea.

He caught up with the cattle in the salty plain. He walked behind them in a straight line, carrying his club, the lion skin slung over his shoulder. In his other hand, he carried a wheel, divided into eight sections by its spokes. He paused where the cattle stopped to drink, at a ford or a spring at the foot of a hill. There were rough stones at his feet, shaped only by torrents and volcanoes, but behind them, on the path the man and the animals were trampling out, along with the rich gift of dung, there were sherds of brick and pot, cut stones flushed with cinnabar, ingots of tin and even gold. Keeping the land to his left, he walked beside the lagoons of the Middle Sea. Sometimes, there was a stone watchtower and a sail on the grey horizon. At dawn, by the shivering inlets, the sun rose again in the northern sky and burned a beacon onto his eye. In the warm nights, he angled his stride by the blurry trail of stars where the sun had passed or where his stepmother, tricked while she slept into giving the misbegotten mortal her breast, had wasted her milk in angry ostentation.

Near the mouths of the Rhodanus, birds and merchants came down from the other ocean: this was the region where the midsummer wind was called Buccacircius because it blew so hard that it puffed out a man’s cheeks when he tried to speak. The tribes of the region were Ligurians, who belonged to such an ancient time that no one could understand their language. To those wild inhabitants of the hinterland, the road that the man and the animals were creating was something terrible and new. He reached the dry plain called the Crau, which is a desert of silt brought down from the distant Alps to the Rhodanus by the river Druentia. His enemies lurked in the low hills, clutching their quivers; they saw him sleep and watched the cattle that had come from the ends of the earth. The Ligurians had no towns, but if anything had stood on that plain, it would have been smashed like a boat that is splintered and wrecked by the storm. While he dreamt of the circling stars, thunderheads darkened the Crau, the skies cracked, and blazing boulders slashed through the air like a thousand gale-blasts all at once. When he woke, his enemies were gone, and the plain was strewn with stones as far as the horizon. In the dawn’s slow light, the cattle were munching the tough green shoots that pushed up between the stones. He had no memory of the battle, but he knew that his prayer had been answered.

For the third time, the sun rose in the same place, as though a god’s strong arm were holding its chariot to the same course until the journey was done.

They crossed the Rhodanus where an island divides it into two rushing streams. Beyond the valley, there were blue hills, each one higher than the last, with crests of yellow limestone: they might have been the backs of giants who had been stranded there when he pulled two continents together to prevent the monsters of the Ocean from entering the Middle Sea. He climbed until the air grew thin and the Druentia was just a torrent. At last, he reached a place from where the rivers flow and the Alps formed an impassable wall. Pausing only to shift the snow of countless centuries, he piled a forest against the mountain, set fire to it and waited for the crack of thunder. Then he cleared away the rubble.

No sooner had the gateway opened in the mountains than people and animals were passing through it in both directions: soldiers in bird-crested helmets returning from the east; brides whose braided hair might have been worked by goldsmiths, travelling in procession to a new home; merchants with small, stubborn horses carrying salt and iron, or red wine in leather bags, each one of which was worth a slave.

From then on, guided by the sun, he crossed the land in eight directions. His club was a feather compared to the weight of Pyrenea’s unbearable generosity, and so he paid his way by performing acts of public good. He created more roads, set their distances and tolls, and killed the savage bands who robbed travellers. He diverted rivers, drained and irrigated fields; he built towns and supplied not only the building materials – the squared stones, the pointed staves, the mounds of earth – but also their populations. For wherever he went, he found fathers more grateful than King Bebryx and virgins curiously skilled in the art of love.

One town above all received his favour. It lay on a levelled hill in the fertile land of the northern watershed. This was Alesia, which became the mother-city of the Celts. The princess of Alesia was a tall and beautiful girl called Celtine. She served the traveller salted fish from the distant sea and sides of venison as large as herself; she poured out the strong wine spiced with cumin. In the mornings, she brought him strawberries from the woods and the water that was used to cleanse the honeycombs. She did this out of love and the desire for a son. But the traveller had grown tired and his head ached with memories. And so Celtine stole his cattle and – this is the only unbelievable part of the tale – hid them and refused to tell him where they were until he agreed to rest his heavy limbs on the soft skins of her bedchamber. Somehow, in that land of tidy fields and gentle hills, a girl concealed from the son of a god a herd of road-hardened cattle that had eaten the sharp grass that grows by the Western Ocean . . . It was the kind of trickery a man of his years could easily excuse. He accepted his defeat, paid generous tribute to his conqueror, and a son was born, named Celtus or Galates.

At last, he grew so old that he was recognizable only by his club, his lion skin and his wheel. There was nothing left for him but to tell stories. He never wanted for an audience: as soon as he opened his mouth, the children and grandchildren of Celtine felt his eloquence tug at their ears, and they gathered round like the herd when the shepherd brings the hay. And they knew that everything he said had really happened, because he himself had made the roads on which he travelled, and the roads were as true as the sun that wheels overhead and underneath the earth, dividing up the heavens and the world below, so that souls are never lost when they journey to the Ocean and the lower world, and from there to the gateway in the east where the sun is reborn.

It is an uncanny characteristic of Celtic myths – including those that recount the adventures of a demi-god – that they often turn out to be true. The bards who preserved tribal memory in verse were not rambling improvisers: they were archivist-poets who knew the dates of battles and migrations. The story that Massalia (Marseille) was founded by Greeks from Phocaea in about 600 BC has been confirmed by archaeological excavations. The legend of a mass resettlement of Gaulish tribes in northern Italy is more accurate than histories written by erudite Romans, who were never sure whether the Celts had come from the east or from the west. In Irish mythology, the great mound called Emain Macha (Navan Fort) was said to have been founded by a certain Queen Macha (identified with a goddess of that name) in 668 BC. This was considered impossibly early until archaeologists dated the oldest features of Emain Macha to c. 680 BC.

The historical truth of Celtic myths was far from obvious to the Greeks and Romans who recorded them. By the time these stories were written down, they no longer made much sense either as legend or as history. Some of them were skewed by Roman propaganda and prejudice; others had become entangled with local myths from an age before the Celts existed. Cluttered with incomprehensible names and impossible events, they spoke of stones hurled down from the heavens and a race of serpents born of human beings. The gods themselves became confused. When the peripatetic writer and raconteur Lucian of Samosata was travelling through Gaul in the second century AD, he was shocked to see a piece of ornamented sculpture which he took to be an insulting depiction of the deified Herakles: the god had the appearance of a grizzled old man with the sun-baked face of a sailor. Lucian was looking at something too exotic to be comprehended: the tongue of the Celtic Herakles was pierced with delicate chains of gold and amber attached to the ears of a happily captive audience. Some of his listeners were so enthralled that the chains had slackened as they surged towards the storyteller. A Greek-speaking Gaul had to explain to Lucian that this was the Gaulish Herakles: his name was Ogmios, and his eloquence was such that his audience literally hung on his every word.

The ear-tugging tales of the Gaulish Herakles were not just a metaphorical expression of the scope and fertility of the Celtic world. They belong to that tantalizing, protohistoric zone between legend and myth. There probably was a tribal chief, some time in the late Bronze Age, who grew rich through cattle rustling, or a warrior-king who pacified the prehistoric tribes that lived along the Mediterranean trade routes. Centuries before the Romans imposed their genocidal peace, the roads had been made safe enough for herders and traders to travel up from Iberia, bringing livestock, salt, amber, iron, tin and gold. The civilizing feats of a heroic figure were celebrated in an Odyssey that was like a storytellers’ warehouse of domestic and imported produce. Greeks who founded trading-posts along the Mediterranean recounted the tenth labour of Herakles (the theft of a giant’s cattle from Erytheia, the ‘red’ sunset island on the edge of the world); Phoenician sailors brought tales of the god Melqart, whom the Greeks recognized as their own Herakles. The serpent creature in the womb of Pyrenea was probably the vestige of a snake-god worshipped in the forested foothills long before the Celtic Bebruces occupied the region later known as Gallia Narbonensis. But the passionate gift that she made of herself to a wandering hero from the ends of the earth would have had the sound of recent history to tribes who formed commercial and matrimonial alliances with the Greeks.

The Heraklean Way – the path that adhered wherever possible to the diagonal of the solstice sun – may have required a god-assisted reconfiguration of the landscape in the form of mountain passes, but it was, on the whole, a practical route. It followed the prehistoric trails of transhumant animals which, as Pliny the Elder noted in the first century AD, ‘come from remote regions to feed on the thyme that covers the stony plains of Gallia Narbonensis’. It avoided the impossibly rugged coastal route into Italy, which Roman legionaries dreaded and which is an obstacle course even today; instead, it climbed up to the grassy plains of Provence and from there to the only Alpine col that remained passable in winter – the Matrona or Montgenèvre, near the source of the Durance. Beyond the Matrona, a trader or an army could descend to the plains of Etruscan Italy or continue towards the land of the dawn and the salt mines of the eastern Alps.

The people who heard these tales knew that these places existed: the Sacred Promontory, where the journey began; the mist-covered mountains of Pyrenea; the holy spring at Nemausos (Nîmes), which was said to have been founded by a son of Herakles; the rock-strewn desert of the Crau and the Matrona Pass. These tales would have been told in the oppida – the Roman name for Celtic hill forts – from which the arrow-straight line of the Heraklean Way can still be seen bisecting the landscape in the form of tracks and field boundaries. The inhabitants of these oppida knew that all these sites were joined by a line that had been blessed and ratified by the gods, because it also existed in the upper world.

Now that the sky is just the unreliable backdrop of the daily human drama, and the sky gods’ only priests are weathermen, knowledge of celestial trajectories seems almost esoteric. Most people are aware of cardinal points only because of a prevailing wind, a sunny breakfast-room or a damp north-facing wall. Ancient Celts always knew exactly where they stood in relation to the universe. A cognitive psychologist has discovered that speakers of languages in which the same words are used for immediate directions (‘right’, ‘left’, ‘behind’, etc.) and for points of the compass tend to be aware of their orientation, even indoors and in unfamiliar surroundings. Gaulish was one of those languages. ‘Are’ meant ‘in front of’; it also meant ‘in the east’. ‘Dexsuo’ was ‘behind’ and ‘in the west’. To head north, one turned to the left (‘teuto’), and, to head south, to the right (‘dheas’).* In English, ‘right’ and ‘left’ are relative to the speaker’s position; in Gaulish, directions were absolute and universal. If a Celtic hostess told her guest that the imported Falernian wine was in the krater behind him, she meant that it lay in the same direction as the setting sun. If he went out hunting, he would have known immediately where to point his spear when his host said, ‘the boar is coming at you from the south’. And when he left the oppidum and rejoined the Heraklean Way, he would have known that he was travelling towards the rising sun of the summer solstice.

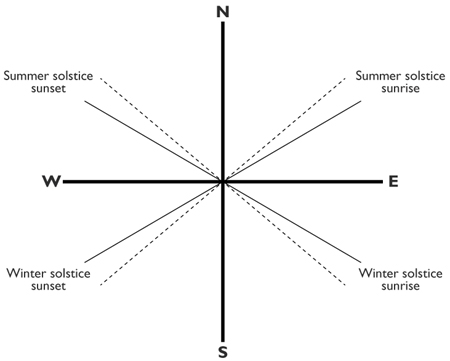

The summer and winter solstices were crucial points of reference for ancient civilizations. The complexities of measuring solstice angles will be mentioned later on;* the principle itself is simple. In the course of a year, because of the tilt of the earth’s axis, the sun rises and sets in different parts of the sky. Around 21 June, it rises on the north-eastern horizon at what appears to be the same point for several days in a row – hence the term ‘solstice’ (the ‘stand-still of the sun’). The summer solstice itself occurs on the longest day of the year. From then on, the sun rises progressively further south, until the winter solstice, which occurs on the shortest day of the year. Halfway between the two solstices, the sun rises due east and sets due west. These two days are the equinoxes, when the night (‘nox’) is roughly equal (‘aequus’) in length to the day.

According to popular wisdom, the solstice was the object of an absurd superstition. Ancient people are supposed to have seen the sun rising and setting ever further to the north or south and to have concluded that without a good deal of prayer, procession and bloody sacrifice, it would either get stuck in the same place – with disastrous consequences for agriculture – or, worse, continue in the same direction until it disappeared for ever. This would mean that there was once a civilization that was capable of building enormous, astronomically aligned stone temples and yet was otherwise so impervious to experience that it had to renew its knowledge of the universe every six months. The solstice may have been a time of ritual celebration or mourning, but it was also an obvious and useful reality. More accurate bearings can be taken during the solstice than at other times of the year, and since the sun rises and sets at almost exactly the same point for over a week (within a range of 0.04°), a day of cloud and mist is less likely to spoil the operation.

The purpose of those measurements was both scientific and religious. The paths of heavenly bodies revealed the workings of the universe and the designs of the gods. The Celts’ trading partners, the Etruscans, used solstice measurements to align their towns on the cardinal points. In this way, the whole town became a template of the upper world. ‘Superstition’ lay in the fact that the town’s skyscape, too, was divided into quadrants for the interpretation of celestial signs (stars, bolts of lightning and flocks of birds): north-east – the approximate trajectory of the Heraklean Way and the summer solstice dawn – was the most auspicious quadrant; south-east was less auspicious; south-west was unlucky, and north-west extremely ominous. Since north lay to the ‘sinister’ left, and since the sun’s light dies in the west, the system had a certain psychogeographical logic.

2. Solstice angles

The angles shown here are the solar azimuth angles (see note on p. 14) in 1600 BC at Stonehenge, latitude 51.18° north (dotted lines) and the Pillars of Hercules, latitude 36.00° north (unbroken lines).

These alignments were part of the common fund of knowledge throughout the ancient world. The Celts often built their sanctuaries so that the summer solstice sun would shine through the eastern entrance onto the altar. Though the Romans sneered at superstitious barbarians, their own surveyors used the solstice as a point of reference. No surviving Roman text mentions the astronomical significance of the Heraklean Way, and the secret seems to have been lost for almost two thousand years. But to the ancient Celts, the meaning of its alignment would have been as obvious as though it was explained on a roadside information panel.

The name itself was explanatory. To Celts and Carthaginians, ‘Via Heraklea’ would have meant, in effect, ‘Path of the Sun’. Like his Carthaginian equivalent, Melqart, Herakles was also a sun god. His twelve labours were equated with the twelve constellations of the zodiac through which the sun passes in the course of a year. The face of his Celtic equivalent, Ogmios, had been scorched by the blazing vehicle that carried him across the sky, and the wheel he held in his hand – like the thousands of pocket-sized votive wheels that are still being found in Celtic sanctuaries – was a symbol of the sun. The eight spokes are thought to represent the cardinal points and the rising and setting of the sun at the summer and winter solstices. And because the sun was the ultimate authority in matters of measurement, Melqart or Herakles was also the divine geometer: ‘in his devotion to wisdom’, said Philostratus the Athenian, ‘he measured the whole earth from end to end’.

Herakles’ solar wheel evidently served him well as a global positioning device. The solstice line of the Heraklean Way is astonishingly accurate. From Andorra (the cols of Muntaner and Ordino) to the Matrona Pass (almost five hundred kilometres), it has a bearing of 57.53° east of north. This is the angle of the rising sun of the summer solstice at a point roughly halfway from the Sacred Promontory to the Matrona Pass.* Holding to this bearing, it runs through or close to eight tribal centres, including Andorra, Narbonne, Nîmes and Briançon; it also passes by six of the mysterious places once called Mediolanum, of which much more will be said. Over its entire length (almost 1600 kilometres from the Sacred Promontory to the Matrona Pass), the bearing is 56.28°, which, at that enormous distance, is so precise as to be incredible.

Even more surprising, in view of its accuracy, is its great age. One of the earliest surviving references to the Heraklean Way dates from the third century BC. It was mentioned by the anonymous author – known as ‘the Pseudo-Aristotle’ – of De mirabilibus auscultationibus (‘Wonderful Things I Have Heard’):

From Italy as far as the country of the Celts, Celtoligurians and Iberians, they say there is a road called the ‘Road of Herakles’, and on this road, the traveller, whether native or Greek, is watched by the neighbouring tribes so that he may receive no injury; for those amongst whom the injury has been done must pay a penalty.

By the time the Pseudo-Aristotle heard of it, the wonderful road had already seen several generations of travellers. Tracks are hard to date, but filtering techniques applied to aerial photography have made the landscapes of ancient Gaul bloom with historical clues. When Greek traders first sailed towards the setting sun and reached lands that even Odysseus had never seen, they set up trading posts called emporia along the coasts of the Gaulish and Iberian Mediterranean. To supply the new ports, they purchased land from local tribes, and then divided up the territory into squares of equal size. The process and its result are known as centuriation. Some of the early Greek centuriations have been plotted in great detail: on a map, they look like the gridlines of American cities covering many hundreds of square kilometres. One of the oldest is the centuriation of Agatha (Agde), which was a colony of the Greek port of Massalia (Marseille), founded in the fifth century BC. For a distance of twenty-five kilometres, the Heraklean Way follows the diagonal line that marks the northern limit of the Agde centuriation. Since centuriations invariably adopted the trajectories of existing roads, this section of the Heraklean Way at least must date back to the very earliest days of Graeco-Celtic cooperation.

These abstract measurements and trajectories are the comprehensible whisperings of a vanished civilization. For a modern traveller, the physical inconvenience itself is a sign of ancient mathematical expertise. The old trail keeps to its cosmic bearing whenever it can. Later tracks and roads, including some stretches of the Roman Via Domitia that replaced parts of the Heraklean Way,* are more obsequious to the landscape – they curve conveniently around the slopes and sidle up to villages along the valleys – but the dust-blown Heraklean Way strides over the hills like a heedless athlete. This is the material form of history, the tangible proof that ancient truths are still recoverable. The accuracy of the Heraklean Way is directly related to the accuracy of Celtic legends. Astronomical observations, spanning many years, made it possible not only to project a straight line across the landscape but also (for example, by recording solar eclipses) to attain the kind of chronological accuracy that could date the foundation of an Irish hill fort to 668 BC or the foundation of Massalia to the beginning of the sixth century BC.

Perhaps it was then, in the early 500s, that the tribes of the hinterland encountered the skills and technology that enabled them to trace the sun god’s path on earth. Or perhaps a human Herakles from Greece had journeyed to the west as a sailor in search of land and a foreign princess. Even at this great distance in time, myths begin to resolve themselves into legends, and in those legends, historical figures can be glimpsed. The two surviving versions of the story of Massalia’s foundation place the day in question – for the convenience of Roman readers – during the reign of the Roman king Tarquinius Priscus (c. 616–579 BC). The original Celtic versions were almost certainly more precise.

On the afternoon in question, a trading fleet from the distant Greek city of Phocaea dropped anchor in what became the harbour of Massalia, the first city in Gaul. The chief of the local tribe, the Segobriges, was about to hold a banquet at which his daughter was to choose a husband. According to tradition, she was to indicate her choice by offering the future bridegroom a cup of pure water. The Greek captains were invited to the ceremony. Seeing the dark-eyed adventurers who had braved the trackless sea, and having perhaps previously inspected their treasures – the painted vases, the bronze flagons and tasting spoons, and the ships like a god’s chariots resting in the harbour – she offered the cup of water to one of the fearless navigators.

The couple were married, and, like Herakles and Celtine, a Greek hero and a Celtic princess embodied the happy truth that the origins of a powerful and stable confederation lay, not on the battlefield, but on a long-distance trading route that led unerringly to a woman’s bed. A colony was founded at what is now the Vieux Port of Marseille. Not long after, Greek wares and locally produced Greek wine were being carried up into remote parts of Gaul from the mouth of the Rhone – where a city called Heraklea once stood – and along the Heraklean Way, where Greek pottery of that period is still being dug out of the rubble of hill forts and cemeteries.

The road from the ends of the earth was the beginning of one of the great adventures and inventions of the ancient world. So much about it is improbable – its length, its accuracy, its antiquity: it might all be attributed to the god of chance were it not for the records of a journey made along that trajectory by a real, mortal human being. One of the two accounts – by the Greek historian Polybius – was based on research trips and interviews with people who had witnessed Hannibal’s expedition fifty years before; the other, by the Roman historian Livy, used some of the same reports, including a lost account in seven volumes by one of the traveller’s companions. Neither historian recognized the transcendent significance of the route.

The journey took place in 218 BC, when the Heraklean Way was already steeped in four centuries of myth and legend – which is partly why it was chosen as the route of the expedition. In the late spring, ninety thousand foot soldiers, twelve thousand cavalry and thirty-seven elephants set off from New Carthage (Cartagena, on the south-east coast of Spain). The Carthaginians’ empire had spread from the coasts of North Africa into Iberia, and their only rivals in the Mediterranean were the Romans. The young Carthaginian general, Hannibal, was to march from Iberia, across the Pyrenees and then the Alps, to attack the Romans from the north. Alliances had been formed with Gaulish tribes who had colonized the plains on the Italian side of the Alps; other tribes had been wooed with promises of gold; many of the soldiers on the expedition were Celts from Iberia or Gaul. The city of Rome, according to Livy, was ‘on tiptoe in expectation of war’.

At some point, Hannibal – or part of his army – joined the line of the Heraklean Way. It was an obvious route: the origins of Iberian place names suggest an ancient frontier running diagonally between Celtic or Celtiberian tribes to the north-west and the indigenous inhabitants to the south-east. This frontier closely matches the Heraklean line, and it leads to what must have seemed an unnecessarily arduous crossing of the Pyrenees. The four tribes that were said by Polybius to have been defeated by Hannibal lived, not on the coast, where a Roman customs post still marks the relatively easy crossing at the Col de Panissars, but in the central Pyrenees, in the region of Andorra, where the Heraklean line crosses the watershed (fig. 1). In warm spring weather, the ascent is not as difficult as it appears on a map, and its remoteness would have had the advantage of delaying news of the Carthaginian invasion.

3. Place names and tribal names of Celtic origin in Iberia

In the context of the entire expedition, the diagonal route was logical and, more importantly, auspicious. Hannibal had already proved himself a brilliant tactician, and part of his brilliance lay in his ability to assume the role of a god. Before leaving Iberia, he had visited the temple of Melqart-Herakles at Gades (Cadiz), to consult the oracle and to ask for the god’s protection. He had wintered part of his army in the harbour of Portus Hannibalis near the Sacred Promontory, where another famous temple of Melqart-Herakles stood on the edge of the inhabited world. Ancient writers who described the Carthaginian invasion knew that Hannibal saw himself and wanted to be seen as the successor of Herakles. He would march across the mountains in the footsteps of the sun god, shining with the aura of divine approval.

Like most of his contemporaries, Polybius had only the vaguest notions of European geography beyond the Mediterranean. He knew about Hannibal’s Herculean ambitions but not about the Heraklean Way. According to his source, ‘a hero [Herakles] showed Hannibal the way’. Polybius – and Hannibal’s later historians – took this to be a rhetorical flourish rather than an indication of the route. Similarly, Livy mistook the key to the whole expedition for a picturesque embellishment and used it in a speech that Hannibal was supposed to have made to his troops when they were quailing at the thought of crossing the Alps: he reminded them that, earlier in the expedition, ‘the way had seemed long to no one, though they were pursuing it from the setting to the rising of the sun’. This was not a figure of speech but the cosmological truth.

There were no maps or atlases on which Polybius could have traced a plausible route, and he thought that foreign place names would only confuse his readers with ‘unintelligible and meaningless sounds’. Fortunately, the distances that he copied from his source make it possible to calculate the point at which Hannibal and his elephants crossed the Rhone – ‘four days’ march from the sea’, then a further ‘two hundred stadia’ (about thirty-five kilometres) north, to a place where ‘the stream is divided by a small island’. Most historians now identify this as Roquemaure, near Châteauneuf-du-Pape, which is certainly correct, since it also happens to be the point at which the line of the Heraklean Way crosses the Rhone.

The next part of the journey is confused and nonsensical in both accounts. The geographical explanations given in the lost source seem to have been treated by Polybius and Livy as a description of Hannibal’s actual route. All we know is that the itinerary was somehow related to the distant source of the Rhone. After crossing the river, Hannibal ‘marched up the bank away from the sea in an easterly direction [in fact, at this point, the Rhone flows north to south], as though making for the central district of Europe’. Polybius went on to explain, more accurately, that ‘the Rhone rises to the north-west of the Adriatic Gulf on the northern slopes of the Alps’.

The details that Polybius and Livy preserved in a muddled form are like barely decipherable remnants of an ancient map. The allusion to the source of the Rhone and ‘the central district of Europe’ may be the trace of an ancient system of orientation that enabled an army or a merchant to plot a course across half a continent. Parts of this ‘map’ will be pieced together in the first part of this book. The crucial point is that only a god could have walked in a straight line all the way to the Matrona; even transhumant herds were forced to take a more winding route towards the Alpine pastures and to skirt the north side of Mont Ventoux. But after bypassing the mountainous terrain, it was vital to be able to continue on the same auspicious bearing as before. Whichever route he chose after crossing the Rhone (Livy suggests that Hannibal followed the river Druentia or Durance), he would have rejoined the Heraklean Way as soon as he could – perhaps near the oppidum at Serre-la-Croix, where the road once again follows the solstice line for twelve kilometres – and then, climbing towards the source of the Durance, to Brigantium (Briançon) and the final approach to the Matrona Pass.

Since the days of Polybius, historians have wondered where Hannibal and his elephants managed to cross the Alps in early November. Etymologists have analysed place names in search of Carthaginian roots, which are no more likely to be found than the petrified elephant droppings that an archaeologist recently hoped to detect along the presumed route of Hannibal. Several expeditions, seeking a suitably heroic crossing, have struggled pointlessly over impossibly high passes, in one case misled by the old ‘Elephant’ inn on the road to the vertiginous Col Agnel, which, even in the days of motorized snow ploughs, is closed from October to May. In July 1959, a Cambridge engineer drove an Italian circus elephant, which refused to answer to the name Hannibella, over the 2081-metre Mont-Cenis Pass. (The elephant, not having received Carthaginian military training, lost 230 kilograms.) In fact, given a choice of routes, an elephant – or, for that matter, a hiker or a cyclist – would head for Italy over the Col de Montgenèvre, which the Celts called Matrona. Not only is this the lowest crossing of the French Alps (1850 metres), it also marks the Gaulish end of the Heraklean Way. The Matrona had everything a military commander could desire: there was a tribal capital – Brigantium – only eight kilometres away, and a broad plain on which crops ripened and which now supports the lush green lawns of an eighteen-hole golf course.

Twenty-three centuries after the Carthaginian invasion, Montgenèvre is a defiantly expanding leisure zone of concrete ‘chalets’ where the Iron Age seems never to have existed. Perhaps its unheroic demeanour explains why it has almost never been identified as the crossing-point. The col itself is now said to lie on the main road through the town, but at the original, unsignposted col, higher up on the narrow road to the Village du Soleil holiday centre, there is something of the electrifying clarity of the high Alpine passes, where distances contract and whole regions suddenly come into view when a bank of cloud disintegrates. At the Matrona Pass, an extraordinary historical vista opens up, though it takes the digital equivalent of a solar wheel to reveal it. If Herakles had stood where the temple of the Mother Goddesses once stood, and turned precisely ninety degrees to the west of the Heraklean trajectory, he would have been looking towards one of the towns he was said to have founded: Semur-en-Auxois, the neighbour of Alesia. If he had followed the setting sun, he would have reached the hill at Lugdunum (Lyon), from where he was said to have looked down on the confluence of the Rhone and the Saône. A bearing of 0° – due north – would have taken him straight to the vast Herculean sanctuary of Deneuvre, where a hundred statues of Hercules (over one-third of all the statues of Hercules ever found in Gaul) were unearthed in 1974. Only a god or a migrating bird returning to its nesting-site could have attained such accuracy.

These hypothetical lines reach far into the depths of ancient tribal Gaul, over ice-bound mountains that had still not been accurately mapped two hundred years ago. Even on a sunny day, it is hard to believe that the precise array of terrestrial solar paths that the Celts would develop is anything other than a beautiful Heraklean coincidence, or some intoxicating piece of false wisdom dispensed by the oracle of the temple, giddy with altitude or Greek wine, conjuring cosmic hallucinations out of the thin air.

When Hannibal stood at the Matrona in the early winter of 218 BC, watching his elephants stumble down to the plains of northern Italy, he knew that he was standing in the rocky footprints of Herakles. His strategists and astrologers, and their Celtic allies and informers, were certain that the sun god had shown them the way. They seem to have known, too, that the source of the Rhone lay in a ‘central district of Europe’ and that it was somehow related to the Heraklean itinerary.

The computerized oracle agrees: a line projected for two hundred and twenty kilometres from the Matrona at right angles to the summer solstice sunset leads to the region of glaciers where the Rhone rises. At the river’s source there was a mountain which, despite its remoteness, was known to the early Iron Age inhabitants of the Mediterranean coast. It was mentioned in a poem of the fourth century AD called Ora Maritima (‘Sea Coasts’). Using what must have been an excellent scroll-finding service, the Roman proconsul, Rufus Festus Avienus, assembled a collection of ancient periploi (descriptions of maritime routes) with the aim of turning them into an unusable but entertaining guide for armchair navigators. One of those ancient texts – of which no other trace remains – was a nine-hundred-year-old handbook for merchants sailing from Massalia to the Sacred Promontory, ‘which some people call the Path of Hercules’. In a passage on the Rhone, the author had mentioned the fact that the mountain at the river’s source was known to the natives of the region as ‘Solis columna’ or ‘the Pillar of the Sun’.

When this name was recorded in the sixth century BC, valuable geographical intelligence was already flowing into the busy harbour of Massalia from distant parts, along with works of art from the eastern Mediterranean and precious metals from the enigmatic Cassiterides or ‘Tin Islands’ – perhaps the islands later known as Britannia – that lay beyond the Carthaginian blockade at the Pillars of Hercules. It might have been common knowledge among the Celts: somewhere in the heart of Europe, many days from the sea routes that were bringing the first trappings of Greek civilization to the barbarous Keltoi, there was a named point of reference, a solar coordinate. The Heraklean Way itself was a wonder of the world, and perhaps there were other wonders, too: Herakles had journeyed throughout Gaul, and his heavenly grasp of the immeasurable earth might have been reflected in other branches and articulations of the Heraklean Way . . . But even four centuries later, in the winter of 218 BC, there was nothing to suggest any such sophistication in the Celtic foot soldiers of Hannibal’s army, trudging over the snow-clogged pass in their rough plaid cloaks and hare’s-wool boots – nothing, that is, except the glint of an arm-ring or a neck torc, the meticulously coordinated orbits of a compass-drawn brooch, or the geometric spirals of a bronze disc attached to a chariot wheel, performing its mysterious circumvolutions like a microcosm of the turning sky.

* The places mentioned in this chapter are shown on the map on p. 4.

* This is the Irish word; the ancient Gaulish equivalent has yet to be rediscovered.

* See pp. 125 and 227, and ‘A Traveller’s Guide to Middle Earth’, pp. 294–6.

* Since the angle changes with latitude, a local standard would have been chosen in order to produce a straight rather than a curved line. (See p. 227.) Even on a short stretch, standardization would have been necessary since the exact point of sunrise or sunset cannot be observed directly: the sun’s light is refracted by the earth’s atmosphere, and the horizon is almost never flat and unobstructed. In 600 BC, the angle was 0.5° less than it is today. The angle in question is the solar azimuth angle (the number of degrees, measured clockwise from north, to the point on the horizon where the sun rises).

* The course of the Via Domitia is shown in fig. 46.