The guide in the horreum was lost in admiration for the Romans. She traced the elegant curve of the vault with a loving gesture, and we peered along a dim passageway at slanting shafts and limestone arches that had braced themselves for centuries against the forum and the market of Roman Narbonne. The buildings above ground had long since crumbled away to form the foundations of later buildings that had disappeared in their turn, but the horreum – if it was indeed a warehouse – had survived until it was the only Roman structure in Narbonne.

‘You’ve got to admire those Roman engineers,’ said the guide, caressing a nicely pointed section of wall that had required only the lightest of repairs.

The Romans had occasionally copied the beautiful stone-and-timber walls of the natives; they had even built some of their own forts using muri gallici; and so it seemed appropriate to put in a word for the guide’s Celtic ancestors.

‘Or,’ I suggested, ‘the Gaulish engineers . . .’

The deathly dungeons suddenly came to life with the sound of laughter. Evidently, this was one of the saving graces of a job in the sunless underworld of sunny Narbonne: tourists sometimes said the most amazing things.

‘Oui!’ she almost shrieked. ‘Les ingénieurs gaulois!’

Stepping out of the horreum into the light of a first-century-BC afternoon, she might have shared the joke with an ancient Roman. To most Greeks and Romans – especially those who had never left home – the typical Celt was a rampaging drunkard who blundered into battle at the side of his brawny, blue-eyed wife, wearing either animal skins or nothing. At home, the Celts festooned themselves with gold jewellery and drank undiluted wine – to which the entire nation was addicted. Their table manners were atrocious: they wore woollen cloaks and trousers instead of togas, and sat on the hides of wolves and dogs instead of reclining on couches. This was in the part of Gaul known as Gallia Bracata (‘Trousered Gaul’). Further north, in Gallia Comata (‘Hairy Gaul’), things were even more exotic. Gaulish aristocrats shaved their cheeks but not their upper lips, so that their pendulous moustaches trailed in the soup and served as strainers when they drank. Sometimes, they showed their appreciation of the meal by fighting to the death over the best cut of meat.

Ever since the sixth century BC, Greek travellers had been returning from Gaul with tales of ludicrous and disgusting practices. Celts who lived by the Rhine tested the legitimacy of their new-born sons by throwing them into the river. Other Celts waded into the sea, brandishing their swords until they were swallowed by the waves. At war councils, punctuality was encouraged by the custom of torturing the last man to arrive and then putting him to death in sight of the whole assembly. In their dealings with strangers, the Gauls were hospitable to the point of insanity: Gaulish men rolled about in bed with other men, ‘raging with outlandish lust’, and it was considered highly offensive if a guest declined to sodomize his host.

It does not take an anthropologist to suspect that what these travellers saw or heard about were baptismal rites, the ceremonial dedication of weapons to gods of the lower world, and the friendly custom of sharing one’s bed with a stranger. The summary execution of late-comers was presumably a ritualized form of punishment like those that were meted out to flabby Celtic youths whose bellies had engulfed their belts, or to people who interrupted a speaker (on the third offence, the heckler’s clothes were slashed to ribbons with a sword). Some practices that were upsetting to outsiders seemed entirely acceptable in context. The Greek philosopher Posidonius, who toured Gaul in the early first century BC, became quite accustomed to seeing human heads preserved in cedar oil nailed to a doorway or stored in a wooden box. The severed head of an enemy killed in battle was considered a priceless trophy and was proudly shown to guests.

These tales from the fringes of the empire are not just a sign of imperial hauteur. The Celts’ unfathomable riddles, the faces that appear and disappear in their complex designs, and the geomantic mysteries of the Druids were forms of sophistication to which the Romans were blind. Educated Celts clearly enjoyed bamboozling foreigners. When Caesar was collecting material on the Hercynian Forest for his book on the Gallic War, a native informant told him of a creature called the ‘alces’ (elk) which, having no joints in its legs, was forced to spend its entire life standing up. Caesar recorded the information as he heard it: to sleep, the alces leant on a tree, so that hunters simply sawed through most of a tree-trunk in a glade where the animal was known to rest, and then returned to collect their prostrate prey.

To the mirthless conqueror of the Gauls, the Celtic mind was a closed book. He knew that the Gauls made fun of the Romans ‘because of our short stature compared to their great size’, but his attempt to explain the taunts of the Aduatuci tribe when they saw the legionaries building a siege-tower is so clumsy that it takes a while to realize that what the Gauls were shouting from the ramparts was, ‘You’re so short, you need a tower to see over the wall!’ If practical jokes are a sign of civilization, the Celts were one of the most advanced societies of the ancient world. Many years after visiting Gaul in his youth, St Jerome still shuddered to recall the Celts from northern Britain who had assured him that the favourite delicacy of their tribe was shepherd’s buttock and breast of shepherd’s wife.

It is a shame that so much of what remains of ancient Gaulish is the linguistic equivalent of a spoil heap. Even the dozen words that entered English by various routes seem to confirm the Roman view of a downwardly mobile race of simpletons and trouble-makers: ‘bucket’, ‘car’, ‘crock’, ‘crockery’, ‘dad’, ‘flannel’, ‘gaol’, ‘gob’, ‘noggin’, ‘peat’, ‘slogan’ and ‘truant’. The only complete sentences of Gaulish to have survived are inscriptions on lead curse-tablets (‘May the magic of the infernal gods pursue them!’), phrases in a medical textbook (‘Let Marcos take this thing out of my eye!’), graffiti on plates and bottles (‘Drink this and you’ll be good company!’), and words of endearment etched on spindle-whorls. These circular discs, which were used to weight spindles, were given to girls as love-tokens. The suitor expressed his desire by identifying his principal attribute with the spindle. Some of the phrases are cunningly suggestive, but, as the largest surviving corpus of Gaulish literature, it hardly evokes a civilization to rival Greece or Rome:

moni gnatha gabi – buđđuton imon (‘Come, my girl, take my spindle!’)

impleme sicuersame (in Latin) (‘Cover me up and spin me round!’)

marcosior – maternia (‘Ride me like a horse, Materna!’)

matta dagomota baline enata (‘A girl can get a good fuck from this penis.’)

nata uimpi – curmi da (‘Pretty girl, give me some beer!’)

Even a dispassionate observer might have asked: what evidence is there that the trousered savages were capable of organizing any sort of infrastructure? The only Iron Age road surfaces to have been identified so far are causeways preserved by the bogs they traversed, a rubbish-strewn shopping street in a hill fort and a few sections of rutted limestone. The Gauls are presumed to have transported their precious wine on tracks that wandered about like barbarians returning from a feast. Schoolchildren and museum-visitors are told that the Romans brought with them, not only Latin, bureaucracy and underfloor heating, but also roads, which they rolled out ahead of the invading armies with the speed of a modern paving machine. Since the Roman builders obliterated the traces of earlier carriageways, the Celtic world appears to have been practically roadless. In the view of one archaeologist, the late-Bronze Age wheelwright of Blair Drummond in Perthshire who made a remarkably narrow-rimmed wheel of ash wood for a cart that would have weighed several hundred kilograms might as well have been manufacturing rolling stock for a railway: the vehicles ‘would all too easily have become bogged down in mud, and it is unlikely that they travelled very far or very fast’ . . .

It might have happened on almost any day in the late Iron Age. A shepherd of the Sequani tribe stands on one of the routes that connect Italy and the Alps to the Oceanus Britannicus. Looking to the south, he sees a billowing cloud of dust, hears the targeted crescendo of hooves and wheels, and hurries his flock to one side as a missile of oak and iron speeds past, piloted by a man with his mind on something distant. Long before the age of steam, Gaulish charioteers had seen the landscape change into a reeling panorama as they travelled far enough north in a short enough space of time to notice the days grow longer, the morning mists thicken and the sky turn a more delicate shade of blue. Before the advent of the Romans, carters employed by Greek merchants were racing by land from Marseille to Boulogne in thirty days. Two thousand years later, in the reign of Louis XV, modern coaches pulled by teams of horses twice the size of Gaulish nags completed the same journey in just a few days less.

Along those trans-Gallic trade routes, in Burgundy, Champagne and the Rhineland, chariots have been found in graves, dismantled and displayed like exploded diagrams. They were delicately sprung and showed an inventor’s love of intricate devices: axle-pins with coral discs and enamel inlays, rein-guides and mountings that looked like foliage or the faces of gods. These vehicles assembled by teams of specialists were not designed to be run on rubbly, winding tracks. When the Gauls settled in northern Italy in the fourth century BC, their technology amazed the Romans, whose cumbrous conveyances seemed to belong to an earlier stage of history. Faced with the new machines, the Romans borrowed a whole vocabulary of vehicular transport: carros (wagon); cission (cabriolet); couinnos and essedon (two-wheeled chariots); petruroton (four-wheeled carriage); carbanton (covered carriage); reda (four-wheeled coach). Nearly all the Latin words for wheeled vehicles came from Gaulish.

One of those modern chariots was found in the region of Alesia, where Celtine met Herakles. Since the chariot dates from the late sixth century BC, Celtine herself might have owned a similar model. She had a neighbour who lived forty kilometres to the north in a vaulted palace overlooking a valley where the Sequana begins to broaden into a navigable river. The archaeologists who discovered her called her ‘la Dame de Vix’, which is the name of the local village, near Châtillon-sur-Seine. Her real name might have been Uxouna, Excinga, Rosmerta or, more likely, Elvissa, which means ‘very rich’. She had beads of blue glass and amber, bracelets of bronze for her ankles and arms, and a microscopically detailed, twenty-four-carat gold torc that would have been almost too heavy to wear. Objects from all over the known world had been delivered safely to her home: the beads came from the Baltic and the Mediterranean, the torc from the Black Sea; her tableware was Etruscan and Greek, and she owned a comprehensive range of imported wine paraphernalia.

The largest vessel ever found in the ancient world is her beautiful bronze krater (a wine-mixing urn) from southern Italy: it held eleven hundred litres – enough for a week-long banquet or a god’s aperitif. When she died in her early thirties, she was laid out on her state-of-the-art chariot. It had wide-angle steering, and the wooden coachwork was suspended above the chassis by tiny, twisted metal colonnettes that seemed to flaunt their gravity-defying frailty. This was a vehicle fit for a journey to another world. It may never have run on the open roads of Middle Earth, but it proves that the technology existed, and that the beauties of mechanical efficiency were appreciated, four hundred years before the Romans brought their civilization to Gaul.

Like a detective story with an unreliable narrator, Caesar’s Gallic War contains the clues that disprove its self-serving theories. Caesar knew that, in the comfort of their heated villas, his readers would imagine impenetrable, rain-soaked realms ravaged by mudslides and torrents, obstructed by swamps and trackless swathes of tangled oak forest. (Northern oak-woods always looked wild to a Mediterranean eye.) He knew that, as they blessed him for bringing gold and slaves from Gaul, they would marvel at his bridge-building exploits and his lightning marches from one end of the wild land to the other.

Yet Caesar found roads and bridges already in place wherever he went. Otherwise, one would have to believe that the Gauls gave the name ‘briva’ to about thirty different towns (Brienne, Brioude, Brive, etc.) and then waited for the Romans to come and build the eponymous bridges. In Gaul, the marching speed of the legions was always well above the average for the Roman empire. An army of several thousand Roman soldiers marched from Sens to Orléans in four days, arriving in time to pitch camp and set fire to the city (twenty Roman miles a day). Caesar himself reached Belgic Gaul from somewhere south of the Alps ‘in about fifteen days’ (at least twenty-six miles a day). The Gauls were even faster: a battle-weary army of a hundred and thirty thousand marched from Bibracte to the territory of the Lingones in just four days (thirty miles a day), which gives some idea of the resilience of the road surface.

In the Astérix cartoons, road-signs indicating a certain number of leagues to the nearest town are supposed to be humorous anachronisms, yet they certainly existed. In seven years of campaigning, Caesar always knew when he was entering or leaving a tribal territory, and – most telling of all – he always knew the exact distances to be covered. Distances in Gaul were so accurately measured and so comprehensively plotted that even after the conquest, the Romans continued to use a standardized Gaulish league instead of the Roman mile.

There is something almost magically revealing about these simple calculations – something akin to discovering a two-thousand-year-old Gaulish road-atlas in a second-hand bookshop, which is, in effect, what the following operation conjures up.

A pleasant way to while away an afternoon and to make a major contribution to the history of the Western world is to find a perfectly straight section of Roman road on a map, and then to project the line in both directions on exactly the same bearing. Roman roads can usually be distinguished from other straight roads by their medieval names: in Britain, any road in open country called ‘Street’ is almost certainly Roman, or an ancient road whose alignment was adopted by the Romans; in France, many are conveniently ascribed to ‘Jules César’ or to a semi-mythical Queen Brunehaut. If the road itself is unnamed, there are always place names such as ‘Chaussée’, ‘Estrées’, ‘Stone’, ‘Stratford’, ‘Stretton’ and so on, which indicate settlements that grew up along a Roman road.

Most of these roads take the shortest route between two Roman towns or camps. But sometimes, a ‘Roman’ road shows a curious attraction to a Celtic site. The road from Amiens to Saint-Quentin heads straight for the Gaulish oppidum of Vermand, fifty-eight kilometres to the east. There, in order to reach the Roman town of Saint-Quentin, it turns abruptly nineteen degrees to the south-east. The line to Vermand is so impressively undeviating that this dog-leg at the far end of the road can hardly have been the result of a surveying error.

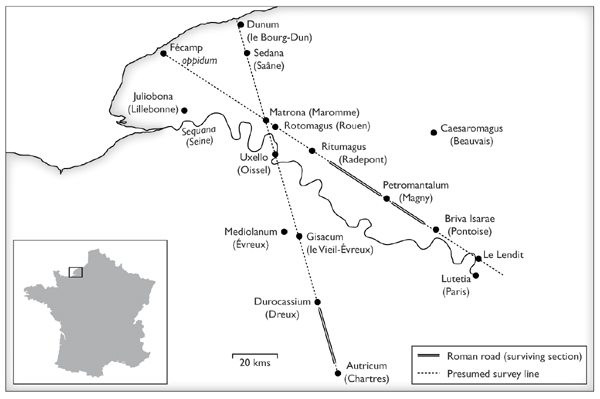

It may be that the road was built at an early stage of the Roman conquest, before Saint-Quentin existed, and that the Vermand oppidum was used by the Romans as a marching camp. But many other realignments are harder to explain. The main road to Lutetia (Paris) from the Norman coast, part of which survives as the N14 autoroute, is aimed, not at the Roman centre of Paris on the Left Bank, but at the tribal meeting-place of Le Lendit in the northern suburbs. There, it crosses the Col de la Chapelle, which lay on the prehistoric tin route. In the other direction, it passes through a series of important Celtic sites, including Rotomagus (Rouen), which means ‘Wheel-market’, and Matrona (Maromme), which shares a name with the pass created by Herakles. After Matrona, the Roman road turns to the west to reach the Roman port of Harfleur, but if the projected line is followed to its logical conclusion, it arrives with what appears to be perfectly engineered precision at the monumental entrance of one of the most important hill fort towns in northern France, the oppidum of Fécamp.

4. ‘Roman’ roads oriented on pre-Roman sites

A visitor arriving in the Celtic past is bound to wonder sometimes whether the time machine’s chronometer has malfunctioned. The trajectories of these ‘Roman’ roads are a closer match for Celtic Gaul than they are for the Roman province. The line of the road from Chartres to Dreux misses out the Roman town of Évreux and passes instead through the Gaulish sanctuary of Gisacum, before meeting the Paris line at Matrona. The more the puzzle is examined, the less Roman it looks, and the less surprising Caesar’s rapid conquest of all the lands between the Alps and Brittany. Either the Gauls already had a coordinated infrastructure worthy of their sleek chariots, or they thoughtfully arranged their settlements and sanctuaries so that once the country had been conquered, the Roman engineers could easily join them all together with straight roads.

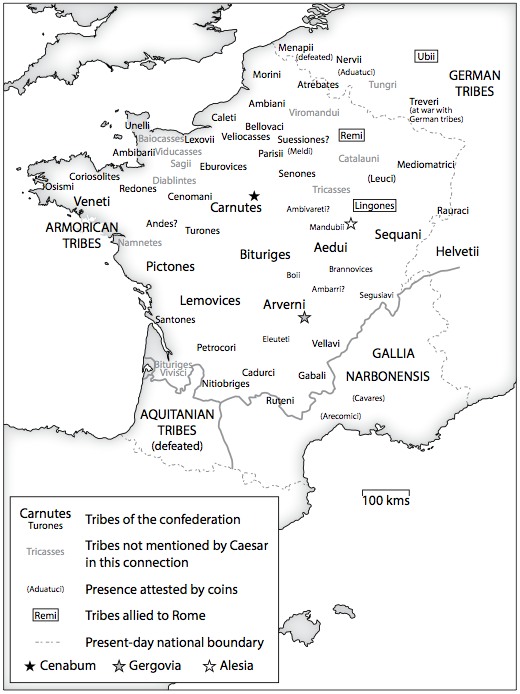

At the end of the winter of 53–52 BC, the Romans were given a memorable lesson in Gaulish ingenuity. A victorious Caesar had returned to Italy, secure in the belief that ‘the country having been devastated . . . Gaul was now at peace’. Meanwhile, the Gauls were planning one of the biggest allied offensives in European history. The insurrection began at Cenabum (Orléans) when warriors of the Carnutes tribe rose with the sun and massacred the Roman merchants who had settled in the town. At that moment, far to the south, the leader of the Arverni was waiting to hear from Cenabum before coordinating the general revolt that would culminate in the battle of Alesia. Caesar describes the means by which news of the massacre reached the territory of the Arverni:

The report was conveyed to all the states of Gaul with great speed. For whenever anything especially important or remarkable occurs, they transmit the news by shouting across the fields and regions; others then take it up and pass the news on to the next in line, and this is what happened on this occasion. For the things that were done in Cenabum at sunrise were heard in the lands of the Arverni before the end of the first watch [between 6 pm and 9 pm] – a distance of approximately one hundred and sixty miles.

Caesar was often amazed – not just on this occasion – by the ‘incredible speed’ at which news travelled in Gaul. The Gaulish message system did not rely on the unpredictable spread of rumour: it had to be in a constant state of readiness so that news could be transmitted at any moment. The human transmitters must have been lodged and fed at carefully chosen locations, and relieved at regular intervals. By Caesar’s account, which gives almost the exact distance as the crow flies to the chief Arvernian fortress of Gergovia south of Clermont-Ferrand (160 Roman miles or 237 kilometres), it transmitted news at about 24 kph. This is not much slower than the world’s first telecommunications system, the Chappe telegraph, which, in 1794, was sending semaphore messages from Paris to Lille at 36 kph.

Anyone who has ever tried to shout across a field will know that transmitting messages in this way is not as simple as it might sound. A long-distance vocal telegraph implies at least as much surveying skill as the pre-Roman road network. If the message follows a straight line over hill and dale, hundreds of transmitters are required. Shouting anything comprehensible from a hilltop, even a few metres downhill, is practically impossible: sound travels far more efficiently along valleys and quiet rivers. But if the line meanders too much around the hills and woodlands, this, too, requires a small army of operators.

Like the road system, the vocal telegraph would have evolved over a long period. At an early stage, perhaps in the sixth century BC, a sound-map of Gaul began to take shape. In areas where settlements were small and isolated, and where shepherds moved their animals over great distances, the acoustic peculiarities of a landscape would have been as familiar as the sounds of neighbours to a modern city-dweller. Using this local knowledge, each tribe would have pieced together a network that joined one hill fort to the next and then, as trade, administration and war demanded, one tribal capital to all its neighbours.

A similar situation arose again in rural France after the end of the Middle Ages. The limits of the tribal or sub-tribal territories that survived as pays (from the Latin, pagus) were marked by church bells, the size and power of which were directly related to the extent of the pays. When news of a threat had to be broadcast more quickly than a messenger could carry it – a foreign invasion or the arrival of a recruiting sergeant, a tax-collector or a pack of ravening wolves – the overlapping circles of sound acted as a crude telegraph system. But this was a system that grew by accident; the Gaulish telegraph was deliberately devised and maintained. Apart from its official purposes, it served what was perceived as a social need. By all accounts, the Gauls had an enormous appetite for news of any sort: they waylaid travellers, mobbed them in market squares and, after feeding them copiously, pumped them for whatever information they might have of distant parts. With the logistical support of the allied tribes of Gaul, such a system could easily have performed the miracles recorded by Caesar.

The whistling language of Pyrenean shepherds, which became extinct in the 1950s, could transmit the contents of the local newspaper up to a distance of three and a half kilometres. The Gauls probably used a monosyllabic code, with repetitions and set phrases to avoid misinterpretations, and the trained lungs of warriors, male and female. Celtic armies famously intimidated their foes by shouting, ululating and blowing their war-trumpets: ‘For there were among them such innumerable horns and trumpets, which were being blown simultaneously in all parts of their army, and their cries were so loud and piercing, that the noise seemed to come not merely from trumpets and human voices, but from the whole countryside at once’ (Polybius). A bellowing Gaul could certainly have matched the range of a whistling shepherd, in which case fewer than eighty sound transmitters would have been required to send the message all the way from Orléans to Gergovia.

In his deceptively brisk style, Caesar was describing one of the wonders of the ancient world. The message to Gergovia used only one line of the network. While the news from Orléans was racing across the swamps of the Sologne towards the Massif Central, the same message was being ‘conveyed to all the states [or tribes] of Gaul’ (‘ad omnes Galliae civitates’). This simultaneous, mass communication is a significant event in the early history of information technology. To judge by the rapidly assembled confederation of Gaulish tribes in 52 BC, the vocal telegraph served an area of over half a million square kilometres.

It may yet be possible to recover something of this masterpiece of acoustic engineering. New sounds have joined the orchestra of winds, running water and birdsong, but the aural configurations of most landscapes have changed very little in two thousand years. The whisper of Clermont-Ferrand, punctuated by a police siren or a clanging girder, drifts up to the plateau of Gergovia. The metallic glissando of trains speeding along the ancient route from Paris to the Mediterranean can be heard from the hill fort of Alesia. Sometimes, in the Pyrenean foothills or the mountains of Provence, where walls and rock faces act as sounding-boards, a conversation in a village square can be followed in perfect detail far beyond the village itself.

5. The Gaulish confederation at the battle of Alesia

A hypothetical telegraph line drawn from Orléans to Gergovia and projected in the other direction passes through several tribal centres and the road junction called Matrona. Two-thirds of the way to Gergovia, it crosses a farm on a low ridge above the winding valley of the river Aumance. One kilometre south-east of the farm, on slightly higher ground, are the remains of a small oppidum. The farm has become a holiday home with (according to the owners’ advertisement) ‘long and wide’ horizons: ‘the only night-time sounds are those of an owl or nightingale’. In the daytime, several other sounds can be heard at a distance of four kilometres, including traffic on the road to Clermont-Ferrand and the lowing of a herd of cattle.

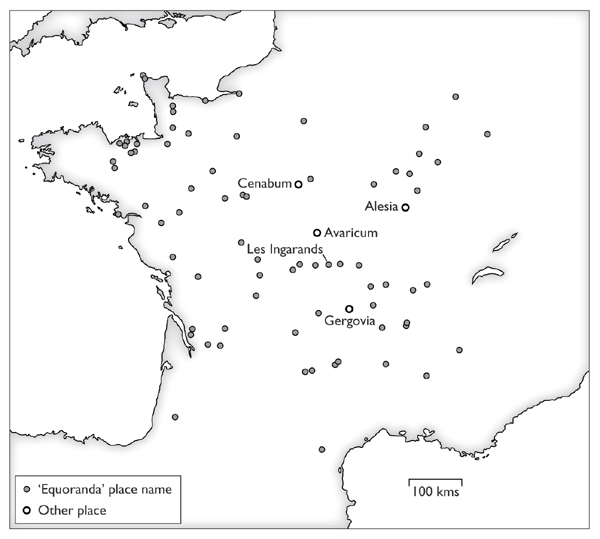

The name of the farm, Les Ingarands, is known to a handful of etymologists as one of the seventy-five place names that can be traced back to a Gaulish word, ‘equoranda’ or ‘icoranda’: Aigurande, la Délivrande, les Équilandes, Guérande, Ingrandes, Yvrandes, etc.* The randa part of the name means ‘limit’ or ‘boundary’. Despite their great antiquity, many of these sites lie on or close to the boundaries of medieval dioceses and modern départements, which makes them probably the oldest examples in Europe of the surprising longevity of administrative divisions. The first part of the name – ‘equo’ or ‘ico’ – is still a mystery. It used to be interpreted as ‘water’ or ‘horse’, neither of which is morphologically possible. The ‘kw’ sound suggests a word that was already archaic in Caesar’s day since, in the Celtic languages that were spoken in Italy, Gaul and Britain, ‘kw’ turned into ‘p’ at a very early stage, perhaps around 900 BC. Equally mysterious is the distribution of Equorandas: most Celtic place names occur all over the Celtic-speaking world, but, for some reason, Equorandas are found only within the confines of Gaul.

The mystery is not necessarily unsolvable. ‘Equo’ or ‘ico’ could be related to the Greek ‘êchô’ (‘sound’, ‘noise’ or ‘loud cry’) or to the Gaulish verb eiğ(h)ō’ (‘I implore’, ‘I call’), in which case, an equoranda would be a ‘sound-line’ or a ‘call-line’. Most of them are on low ridges or in shallow valleys, and all the Equorandas that were visited during the writing of this book would have made excellent listening-posts. Practical considerations ruled out the use of a Celtic war-trumpet, and neither member of the expedition was loud or brazen enough to project the message ‘Agro Cenabo!’ (‘Massacre at Orléans!’) very far, but there was usually a convenient sheep, child or car-alarm to give some measure of the location’s acoustic potential.

6. Place names derived from ‘equoranda’

If the places called Equoranda were stations on the vocal telegraph network, this would explain why the name is found only in Gaul, which is the only part of the Celtic world known to have possessed a vocal telegraph network. Though the clue has been erased by mistranslation, the name itself is curiously reminiscent of Caesar’s description. The slightly peculiar phrase ‘per agros regionesque’ appears to mean ‘through fields and regions’. Some translators smooth away the oddness of the expression by turning ‘regiones’ into ‘villages’. But ‘regio’ was also a term used in augury and surveying: a ‘regio’ was the line of sight that served as a boundary, either on the earth or in the sky. When Caesar’s interpreters were collecting information, ‘regio’ would have been the obvious Latin equivalent of the Gaulish ‘randa’: ‘they transmit the news by shouting across the fields and along boundary lines’.

When the Celts first arrived in Gaul, this may have been the technique that was used to establish frontiers. Until the early nineteenth century, in the French Jura, when a forest was being divided up before felling, two men would stand a certain distance apart and call to one another. A third man would try to position himself in the middle by listening to the shouts and answering them. All three would then call out at regular intervals while a fourth man walked along the path of sound, marking the trees, and when that section of the forest was felled, the result was an astonishingly straight line. The same acoustic surveying technique was used by Persian road-builders, and it was this that gave the prophet Isaiah the image of a voice crying out in the wilderness, ‘Make straight in the desert a highway’.

The seventy-five Equorandas that survive as modern place names could only be the scattered remnants of this magnificent network. There are no precise equations for determining the rate at which place names disappear, and so it would be hard to estimate the original number of transmitting stations. The fact that they survive at all suggests that they remained in use for several centuries and that their purpose was generally known and understood.

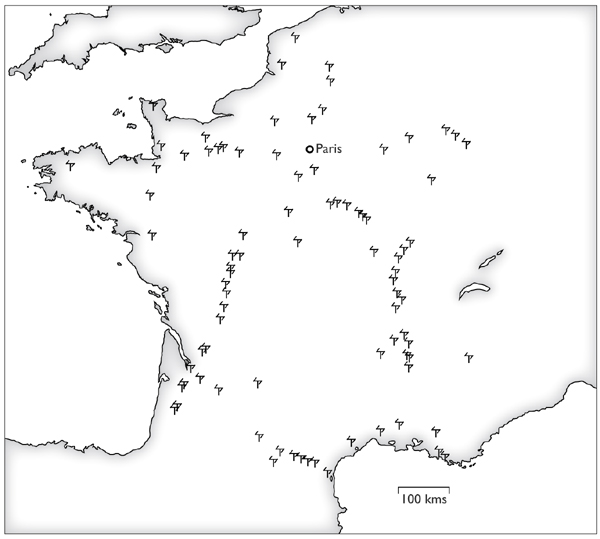

Two thousand years from now, faced with the near-total erasure of digitized information, an archaeologist working on the late-second millennium AD may notice a recurrence of peculiar place names, attached to moderately high places which appear never to have been inhabited. Their mysterious syllables might eventually be traced back to two Greek words: tele and graphein. If enough of these names survive, the archaeologist might suggest that once, within the confines of France, there was a ‘distance writing’ network which involved the use of optical signals. Today, almost one hundred and sixty years after the last message was transmitted to the whole country, announcing the Fall of Sebastopol in the Crimea, there are still enough names on the map, attached to fields, hilltops, mountain passes and some small, inscrutable ruins, to make it possible to trace the skeletal outline of the Chappe telegraph system. But only eighty-six of the original five hundred and thirty-four stations have left their name on the landscape. Many of the names are no longer commonly used; some are known only to farmers and cartographers. The gaps are growing bigger all the time. Without the zeal of local historical societies, at the current rate of disappearance (about ten per cent of the original total every twenty years), the name ‘Télégraphe’ would be practically extinct within a generation.

7. ‘Télégraphe’ place names in 2013

Technological sophistication is no guarantee of survival. Apart from the comparatively gargantuan livestock, the view beyond the computer screen on which these words are appearing is practically unchanged since the Iron Age. A few hundred metres away, at the top of a wooded slope, trains once carried passengers and timber through the borderlands from one former tribal capital (Carlisle) to another (Edinburgh). Although the line was closed less than fifty years ago, practically all that remains in the vicinity is an embankment eroded by cattle, some bricks and lead conduits washed down by the torrents, and a name attached to a pair of cottages. In another two thousand years, the idea that the nineteenth century was an age of empire-spanning transport and communication systems might seem as far-fetched as the concept of a Gaulish engineer.

* The complete list, with coordinates, can be found at http://books.wwnorton.com/books/the-discovery-of-middle-earth/.