With the benefit of a Druidic education, something wonderful appears on the face of Europe, something that has not been seen since the late Iron Age – a map more than two thousand years old and in an almost perfect state of repair. In its fullest form, it shows a comprehension of the earth without precedent in the ancient world. This was the heavenly vision that would help to determine the patterns of settlement and movements of population that created modern Europe.

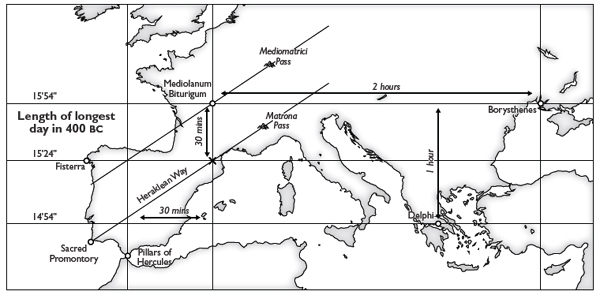

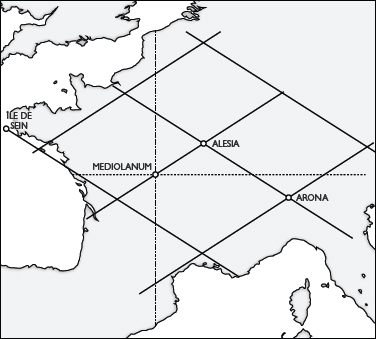

Mediolanum Biturigum – the unlikely hub of the Gaulish wine trade, now called Châteaumeillant – was the sacred centre of Gaul in the time of the Bituriges. It stood on the longest possible meridian and on an equinoctial line running from the Atlantic to the Alps (p. 62). A Druid versed in Greek science would have known that it had been chosen for other reasons too. Mediolanum Biturigum lies two hours due west of one of the key intersections of latitude and longitude in the Greek oikoumene: the mouth of the Borysthenes. It also lies thirty longitudinal minutes east of another key intersection – the Pillars of Hercules, where the Mediterranean meets the Atlantic. And on the line of latitude that runs one hour to the south of Mediolanum stands Delphi, the centre of the ancient world.

The system of Mediolana had been a patchy organization of local territories. Now, perhaps as early as the fourth century BC, the system was developed with such scientific rectitude that a magnificent pattern began to spread across the Continent like the roots and vessels of a great living tree. The Druids could hardly have chosen a better omphalos. Taking their bearings from the Greeks, they created a new, Celtic centre far to the west of Delphi. This siting of a prime Mediolanum is one of the earliest perceptible events in the gradual shift of power from the Aegean and the Mediterranean to the North Sea that would continue for the next two thousand years. It affirmed the place of Gaul in the wider world, and, for the first time, joined the lands of the barbarian Celts to the civilized homeland of Herakles.

35. Mediolanum Biturigum and the Greek oikoumene

The exploration of this tree begins with a simple calculation. The commonest division of klimata or lines of latitude based on the length of the longest day was thirty minutes. The line of latitude that runs exactly thirty minutes to the south of Mediolanum reaches the Atlantic near one of the ‘ends of the earth’ called Fisterra or Finisterre. But the point of intersection that lies due south of Mediolanum (marked ‘X’ on the map) seems utterly devoid of historical significance. In the foothills of the Pyrenees, in a convoluted region of limestone gullies where the medieval Cathars hid from their persecutors, the river Aude crashes through the Gorges de la Pierre-Lys. The jagged escarpment that seems to block the northern entrance is called ‘la Muraille du Diable’ (‘the Devil’s Wall’). Until the eighteenth century, when a local priest persuaded his parishioners to cut a road through the canyon, the hamlet of Belvianes was a cul-de-sac. Yet Celtiberian coins have been found there: Balbianas, as it was known in the eleventh century, was probably the estate of a Romanized Celt called Balbius. The inhabitant of this Pyrenean ‘bag-end’ lived just four kilometres from the small town of Axat beyond the southern entrance to the canyon. Axat owes its name to the Atacini tribe and was probably their tribal capital.

The former territory of the Atacini now knows little of its protohistoric past, but it could plausibly trace its history back to a certain day in 218 BC when a Carthaginian army crossed the Pyrenees, because the point marked ‘X’, half an hour of daylight south of Mediolanum, stands precisely on the Heraklean Way.

The idea presents itself like a gold coin glinting on the ridge of a freshly ploughed field. The location of the prime Mediolanum matches not only the Greek lines of latitude and longitude, but also, with even greater precision, the solstice line of the Heraklean Way. This impeccable geographical coincidence suggests a radiant invention that would otherwise appear to have existed only in the abstract form of philosophers’ diagrams – a system of klimata based not only on equinoctial lines running west to east, but also on the diagonal lines of the solstice. Logically, if the latitudinal position of Mediolanum Biturigum was determined by the Heraklean Way half an hour to the south, the route created by the mythical founder of the Celts should be mirrored by another solstice line half an hour to the north.

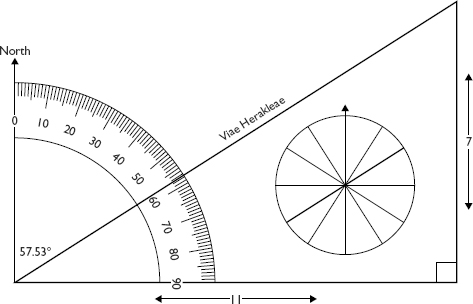

As though by divine decree, a line projected from Mediolanum Biturigum on the same standardized solstice bearing as the Via Heraklea (p. 14) leads directly to the foot of the oppidum on an oval hill in Burgundy where a Celtic princess, the sister-in-love of Pyrenea, took Herakles to her bed. This was Alesia, ‘the hearth and metropolis [literally, ‘mother-city’] of all Keltika’ (fig. 37): ‘It has always been held in honour by the Celts . . . and for the entire period from the days of Herakles, this city remained free and was never sacked.’ This cosmopolitan place, whose citizens came ‘from every tribe’, is the likeliest site of the ‘locus consecratus’ where, according to Caesar, the Druids assembled ‘at a fixed time of the year’ to settle legal disputes.* The territory was administered by a small tribe called the Mandubii (‘The People of the Horse’). As the tribe that occupied the region of the watershed and guarded the routes that joined the Mediterranean to the British Ocean, the Horse Folk enjoyed the protection of their powerful neighbours. The fabled impregnability of their oppidum was presumably a result of the tribe’s internationally recognized neutrality, and it was partly for this reason that Alesia would be chosen by Vercingetorix, leader of the Gauls, as the site of their final battle with the Romans.

From his elliptical path above Middle Earth, the sun god who had loved the princess of Alesia enjoyed a glorious view. Mirroring its southerly counterpart, the northerly line running parallel to the Heraklean Way passes through the tribal capitals of the Agesinates, the Mandubii (Alesia) and the Lingones, through the ‘oak’ sanctuary of Derventio (Drevant), and the towns that are now Nevers and Semur-en-Auxois (another place said to have been founded by Herakles). Finally, twenty longitudinal minutes to the east of Mediolanum, the solstice line arrives with the accuracy of a Gaulish spear at the main gate of one of the most important Celtic sites in Europe.*

The Fossé des Pandours in the Vosges massif, where the route nationale snakes down towards Strasbourg, was once a vast oppidum covering a hundred and seventy hectares. It was the capital of the Mediomatrici tribe – the ‘Mothers of Middle Earth’ – and it guarded the pass now called the Col de Saverne. This is the main gateway from France to Germany and from the Lorraine plateau to the valley of the Rhine. Its Gaulish name is unknown, but, as the pass of the Mediomatrici, it may have had the same maternal connotations as the Matrona. Both passes were portals through which the sun was reborn and poured its light over the lands of the western Celts.

This northerly counterpart of the Matrona Pass, providentially positioned on the northern equivalent of the Heraklean Way, was the physical confirmation of a cherished legend: after completing his journey from the Sacred Promontory to the Alps, Herakles had wandered all over Keltika, bestowing his protection and prestige on the tribes that lived along the great rivers of northern Gaul. And this geo-political symmetry was just one feature of a celestial design that was drawn on the lands that stretched from the Alps to the Atlantic and from the ‘outermost islands’ to the Pillars of Hercules.

This mapping of a great land mass by solstice lines has a peculiarly Celtic appearance. It adopts the Aristotelian or Pythagorean system of twelve wind directions, but instead of dividing the circle of the earth into twelve equal segments, the solstice lines follow the bearing of the Via Heraklea. The original path of Herakles hugs the curve of the Mediterranean coast and heads for the rising sun of the summer solstice, following the longest possible line through Keltika from the end of the world at the Sacred Promontory. This was the baseline of the Druidic system, just as a section of its successor, the Via Domitia, was used as a baseline by the makers of the eighteenth-century Cassini map. The tangent of the real and legendary route creates a more subtle harmony than the equal divisions of the Pythagorean compass rose (p. 133), a geometric petalling of the circle which contains a beautiful truth. Just as the arcs and tangents of Celtic art obey the coded laws of nature, the pattern of meridians, parallels and solstice lines expresses one of the fundamental secrets of the sun god.

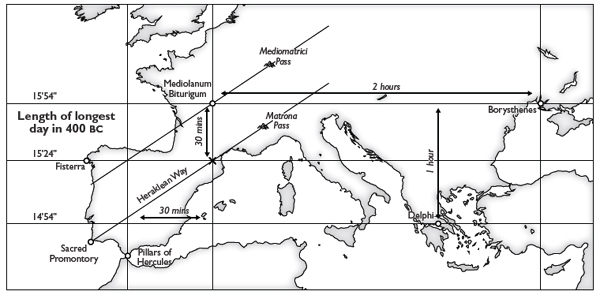

The standardized tangent of the original Via Heraklea is identical to the tangent of its northerly sister. In modern terms, the angle is 57.53° east of north. Even in short-distance ancient measurements, accuracy to within any fraction of a degree is considered significant, and a survey tolerance of at least one degree is usually applied. The extreme precision of the Celtic lines seems at first impossible in the absence of theodolites and compasses, but to Druids versed in Pythagorean geometry, the solution would have been obvious, and it must often have been applied when they were settling boundary disputes.

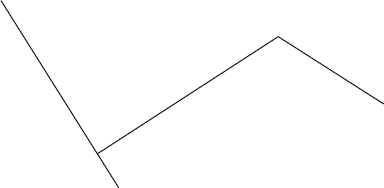

Eleven steps to the east and seven steps to the north – or the same number of knots in an Egyptian rope-stretcher’s rope – make two sides of a right-angled triangle whose tangent angle is 57.53°. This whole-number ratio – 11:7 – is the simple formula that produces a Heraklean line.

Though it appeared to be a figment of legend, geography and the motion of the sun, there is something almost miraculously convenient about the path of Herakles. For a Druid mathematician, seeking correlations between the ideal world of numbers and the random arrangements of material reality, this ratio of two prime numbers, 7 and 11, would have had a particular significance.

The value of pi (π) – the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter – was a Holy Grail of ancient mathematics. The elusive, irrational number required for a precise calculation of the circumference and area of a circle was one of the most mysterious and powerful utterances of the gods. The actual value of pi, to four decimal places, is 3.1416. The Egyptian Rhind Papyrus (c. sixteenth century BC) records a calculation that gives a value of 3.1605. The Babylonians and, later, the Roman army used a ratio of 25/8 (3.125) but were often content with a rough-and-ready 3. Some time before 212 BC, using regular 96-sided polygons inscribed inside and outside a circle, Archimedes proved that the value of pi lay between 223/71 and 22/7 (or 3.1408 and 3.1428). This was an impressively close approximation and a notable event in the history of mathematics.

36. The Heraklean ratio

Yet it now appears that the latter figure had been inscribed on the face of the earth more than a century before Archimedes. One of the treasures left behind by Herakles was a pathway based on pi divided by 2, the ratio of half a circle’s circumference to its diameter (11/7 equals 1.5714, which is half of 3.1428). As though by the purest chance, the Druidic system contained the closest approximation to pi in the ancient world. Herakles had supplied his Celtic sons and daughters with the geometrical secret of his solar wheel, and once that wheel had been reinvented and set in motion on the earth, there was no end to the wonders it might create.

With the formula in hand, the first obvious question is this: was a third Heraklean diagonal created half an hour of daylight to the north, in Belgic Gaul?* Once again, when the formula is applied, a sequence of significant places appears. A solstice line projected from the point that lies half an hour due north of Châteaumeillant passes through or close by several major oppida. Most of these were probably tribal capitals before the Romans: Vannes, which owes its name to the Veneti tribe and which commanded Quiberon Bay; the city of Rennes, which became the Roman capital of the Rediones and was probably the pre-Roman capital, too, since it was there that they minted their coins; le Haut du Château near Argentan, the largest oppidum of the Arvii; Pîtres, the likely capital of the Veliocasses, surrounded by a complex of necropolises; and a ‘Camp de César’ on the banks of the river Samara, in the lands of the Viromandui or whichever tribe inhabited that part of Gaul in the fourth century BC.

Within Gaul, the coincidences are far more striking than any pattern produced by lines drawn at random. At the north-eastern end of the line, near the modern Belgian border, the coherence is less marked: the line passes within one and two thousand metres respectively of Cambrai and Famars, which were towns of the Nervii, before arriving exactly in the centre of the town of Mons, currently thought to have started life as a Roman castrum. (See the large map on p. 154.)

At this stage of the reconstruction, there are three Heraklean lines traversing Gaul, with a centre at Mediolanum Biturigum (Châteaumeillant) and another possible focal point at Alesia.

In the Aristotelian or Pythagorean system, the summer solstice lines are mirrored by winter solstice lines (see the diagrams on pp. 132–3). Taking Alesia – the ‘hearth and mother-city of all Keltika’ – as the point of intersection, the corresponding winter solstice line runs north-west to the chief oppidum of the Senones (the Camp du Château near Villeneuve-sur-Yonne), to the Mediolanum that became the capital of the Aulerci Eburovices (Évreux) and to the cape beyond the port of Le Havre that was known as Caput Caleti (the headland of the Caleti tribe). In the other direction, it runs by the foot of the greatest of the Helvetii’s sanctuaries, on the Mormont hill, and meets the original Heraklean Way at Arona on the banks of Lake Maggiore.

37. Summer solstice lines

38. Summer and winter solstice lines

There is a thrilling sense of hidden mechanisms in seeing an abstract design function so efficiently as a guide to early Celtic history. Arona, where two solstice lines intersect, is known to archaeologists as one of the great cultural crossroads of protohistoric Europe. Beyond Arona and the fortress above the lake, the line passes through the village of Golasecca, which has given its name to the Golaseccan culture of the early Iron Age. It served as a bridge between the Etruscans of Italy, the Hallstatt civilization beyond the Alps and the rich tribes of the Marne and the Moselle famed for their chariot-burials. This was the cultural equivalent of Alesia to the north-west, and so it appears on the Heraklean grid. Continuing to the south-east, the line arrives in the centre of the Mediolanum which is now Milan.

To complete the pattern, two further winter solstice lines should run to the north and south of the Alesia line. But even allowing greater margins of error (up to one degree and one minute of daylight), there are few signs of the same coherence. The contrast is revealing: both lines lie outside Celtic and Belgic Gaul. The northerly line, beyond the Rhine, passes close to some of the biggest oppida in Europe – Magdalensberg, Biberg and Donnersberg – but with nothing like the same precision. Although the Romans exaggerated the cultural differences of ‘Germanic’ tribes, many of whom were clearly Celtic, their history is different from that of the Gaulish tribes, and they may never have accepted the jurisdiction of the Druids. (Caesar was told that there were no Druids in Germany.)

The southerly winter solstice line leads to the lands of pre-Celtic, Ligurian tribes and, in the opposite direction, through Aquitanian Gaul to the Armorican Peninsula. It would have crossed at least sixty kilometres of open sea, to the consternation of a long-distance surveyor. In those Atlantic waters sprinkled with islands and charted mentally by generations of sailors, an accurate survey line would not have been impossible. Even without precise measurements, it would have been obvious that the sun of the summer solstice set over the headlands of Brittany and the lands of the Osismi, ‘the People at the End of the World’. And perhaps, after all, the measurements were precise: a line projected from the point due south of Alesia on the Via Heraklea reaches the tiny Île de Sein, which, in Breton folklore, was the island to which the souls of the dead processed at low tide. In the days of the ancient Celts, it was the home of nine female Druids. The geographer Pomponius Mela described their peculiar convent in the mid-first century AD. Since they lived at the end of a solstice line, it was only fitting that they demanded of those who sought their wisdom a degree of navigational skill:

Sena, in the British sea, facing the coast of the Osismi, is famous for a Gaulish oracle, tended by nine priestesses who take a vow of perpetual virginity. They are called Gallizenas [probably ‘Galli genas’, ‘Gaulish maidens’] and are said to possess the singular power of unleashing the fury of the winds and the seas by incantations, of turning themselves into any animal they choose, of curing what is elsewhere considered incurable, and of knowing and predicting the future. But they reveal the future only to navigators, and only if they deliberately set out to consult them.*

The probability that the solstice lines of Gaul would pass through so many important Celtic places by chance is exceedingly remote. (Just for the record: within Gaul, even allowing one thousand metres on either side of each line, the likelihood of only five tribal centres occurring on the lines by chance is 1 in 87 million; the probability for the sites that are bisected by the lines is approximately 0.4324, which is effectively zero.) But probabilities are often false prophets. The reality of historical research is that, if a coincidence is amazing, it probably is a coincidence, and when two thousand years have elapsed, material proof is thin on the ground.

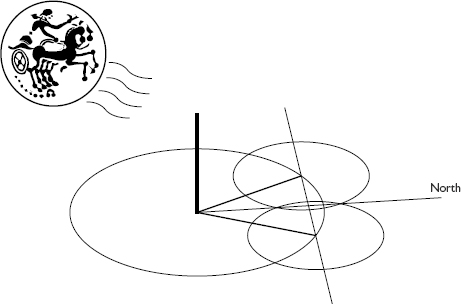

The feasibility of the system is not in doubt. Most of the problems confronting long-distance land surveyors who wanted to draw a straight line between two mutually invisible points could be solved by trigonometry. Devices for measuring angles, such as the dioptra-and-protractor, developed in the third century BC, were used primarily by astronomers. Terrestrial surveyors rarely bothered with such refinements. The protohistoric positioning unit was the groma – a vertical stick with horizontal cross-bars and plumb lines which made it possible to draw straight lines and right angles. Little else was needed – just a right-angled triangle with two sides whose lengths were measured in whole numbers. One of the two sides was aligned on the local meridian. Due north could be found by marking the point at which the shadow of the gnomon was shortest, or, more accurately, because of the fuzziness of the shadow, by finding the middle of a line drawn between the shadow points at two symmetrical hours of the day (for example, 10 am and 2 pm). The operation could be repeated ad libitum as the survey progressed. Over long distances, errors would be averaged out and cancelled.

Inaccuracies resulting from the application of flat, Euclidean geometry to the spherical earth are inconsequential over a few degrees of latitude. Within the zones occupied by Gaul, Iberia or Britain, the curvature of the earth can be ignored. From Mediolanum Biturigum to the pass of the Mediomatrici – a distance of over four hundred and fifty kilometres – the deviation would be approximately 2.5 metres or the length of three Celtic swords. This is partly why some of the medieval sailors’ maps known as portolan charts were so remarkably accurate within areas similar in size to those covered by the Druidic survey.*

There are some spectacular examples of the effectiveness of these ancient measuring tools. In the second and third centuries AD, Roman surveyors laid out the fortified frontier called the Limes Germanicus. For eighty kilometres, it follows a perfectly straight line through the hills of the Swabian-Franconian forest; on a twenty-nine-kilometre stretch south of Walldürn, the directional error is less than two metres. In the early eighth century AD, using practically the same technology, but with the help of an astronomer, a Buddhist monk, I-Hsing, surveyed a meridian of two thousand five hundred kilometres from the southern border of Mongolia to the South China Sea, which is the distance that separates the northern tip of the British mainland from the Pillars of Hercules. Some qanats (ancient underground aqueducts) in China and on the Iranian plateau stretched for tens of kilometres and were accurate to within a few centimetres, despite requiring a three-dimensional survey. The Celtic pathways had the advantage of existing only as imaginary lines in two dimensions. Astronomical observations would have made them even more accurate, and perhaps, like medieval determinations of the qibla (the direction in which Muslims face when praying), they inspired further trigonometrical refinements.

39. Determining true north

Of course, the fact that the Celts were theoretically capable of plotting long-distance lines does not prove that the lines existed. The forms that proof might take can easily be imagined but not obtained. A Druid of the late Roman empire, seeing his store of knowledge depleted by age, might have inscribed the pattern on a piece of parchment, disguising it as a decorative illumination. The design might have been effaced as the work of a pagan or left to moulder in a monastery, its meaning lost for ever – unless some details of the system had been preserved in a verbal map, like the triads that record the origins of the Gauls, the legends that allow the course of the Via Heraklea to be plotted, or the Irish poem in which Cú Chulainn, son of Lugh, recounts his route to the maiden Emer: ‘[I came] from the Cover of the Sea, over the Great Secret of the Peoples of the Goddess Danu, and the Foam of the Two Steeds of Emain Macha; over the Garden of the Great Queen and the Back of the Great Sow; over the Glen of the Great Dam, between the God and his Druid’ . . . But to place most of those sites on a map is a practical impossibility.

Expeditions into the bleary realms of speculation sometimes return empty-handed only to find the answer waiting at home. I had seen the ‘map’ several times without realizing what it was. It takes the form of written texts that describe one of the great migrations of the Celtic tribes, condensing the events of two centuries into brief but detailed narratives. The basic elements of the tale are known to be true. Between the fourth and second centuries BC, Celtic tribes settled in northern Italy, the Danube Basin, the Balkans and Turkey. It was a long, complex process, and yet, as historians have often observed, it seems to show a common purpose and the hand of a coordinating power.

The historical reality of mass Celtic migrations is well established. In 58 BC, a confederation of Swiss tribes headed by the Helvetii gathered at Genava (Geneva). Their intention was to walk across Gaul and to settle in the lands of the Santones, whose western border was the Atlantic Ocean.* Preparations began two years before the departure. Every acre of arable land was sown with corn, and when the harvests had been gathered in, the migrants’ resolve was strengthened by the simple expedient of setting fire to every town, village and private dwelling (twelve towns and four hundred villages, according to Caesar’s information).

Even Caesar was impressed by the Helvetii’s logistical competence: ‘Writing tablets were found in the Helvetian camp on which lists had been drawn up in Greek characters. They contained the names of all the migrants, divided into separate categories: those able to bear arms, boys, old men and women.’ He quoted the tablets in the first book of his Commentaries on the Gallic War:

| Tribe | Heads |

| Helvetii | 263,000 |

| Tulingi | 36,000 |

| Latobrigi | 14,000 |

| Rauraci | 23,000 |

| Boii | 32,000 |

| Total | 368,000 |

| of whom 92,000 are able to bear arms | |

Whatever the reason for the transplantation of 368,000 people from the Swiss plateau to the Atlantic coast – depleted farmland, a sense of stagnation in the military elite or a reversion to the old nomadic ways – these mass-migrations are a cultural trait of Celtic societies. Belgic tribes, who had come from the east, settled in southern Britain at a time when they were prospering in Gaul. Some of the Parisii left the Seine for the Humber and founded a colony in Yorkshire. Many centuries later, most of the Scots who left their homeland for the New World were not victims of the Highland Clearances; they were Lowlanders who had made enough money in the booming industrial economy to become mobile and ambitious.

The greatest of these migrations was the Gaulish diaspora instigated by the Bituriges. Six ancient authors mention it – Livy, Polybius, Diodorus, Pliny, Plutarch and Justinus. Livy’s is the most detailed account. His source was certainly Celtic, and he must have recognized the legend as a verbal map, but without perceiving its underlying logic.

We have received the following account concerning the Gauls’ passage into Italy. It was in the days when Tarquinius Priscus was king of Rome. The Bituriges were the supreme power among the Celts, who form one third of Gaul, and it was always they who gave the Celts their king.

At the time in question (the early fourth century BC),* the king of the Celts was a ‘brave and wealthy’ man called Ambigatus. The name appears to mean ‘he who fights on both sides’ or ‘the two-handed warrior’. Under his rule, Gaul had prospered. The harvests had been copious, the tribes had multiplied, and, now that his hair was turning white, King Ambigatus had to face the consequences of his success: Gaul was bursting at the seams. ‘It seemed scarcely possible to govern such a multitude of people.’

Following Celtic tradition, in which property passed through the female line, Ambigatus sent for his sister’s two sons, both energetic and enterprising young men. One was Bellovesus (‘worthy of power’), the other Segovesus (‘worthy of victory’). To each prince, the Druids were to indicate a direction, and the tribes, accompanied by an army large enough to ensure their safety, would follow the paths assigned to them by the gods. Where the augural ceremony took place, Livy does not say. The most likely site of a Biturigan palace is Avaricum (Bourges), but in the solemn circumstances, Mediolanum Biturigum (Châteaumeillant) would have been the most appropriate location: just as the Greeks mapped the home country onto the colonized territory, the first city founded by Bellovesus in the new land would be called ‘Mediolanum’.

The Druids obtained the judgement of the gods. Segovesus was pointed in the direction of the Hercynian Forest, beyond which lay the windy plains of central Europe. His brother Bellovesus was given ‘a considerably more pleasant route’: he was to lead his people into Italy. If Plutarch’s version can be believed, the followers of Bellovesus could hardly wait to expatriate themselves: they had tasted Italian wine, ‘and were so enchanted with this new pleasure that they snatched up their arms, and, taking their families along with them, marched to the Alps’.

At this point, Segovesus disappears from the tale. His contingent of men, women and children set off for the boundless forest of oak in which we shall try to find them later on. Meanwhile, the more fortunate Bellovesus gathered together the surplus population of seven tribes in what was evidently an expedition on the scale of the Helvetian migration witnessed by Caesar.

The first group was made up of migrants from the following tribes: the Bituriges, the Arverni, the Senones, the Aedui, the Ambarri, the Carnutes and the Aulerci. They headed off in the auspicious direction and came to the lands of the Tricastini. The Tricastini lived in the Rhone Valley to the north of Arausio (Orange), in a region where, a few centuries later, the migrants would have been able to satisfy their wine-lust to their hearts’ content. The letters ‘TRIC RED’,* etched in the stone of the Roman cadastral map of Orange, show that the Tricastini’s territory once extended from the Rhone to the limestone bluffs of the Dentelles de Montmirail.

There, the followers of Bellovesus looked to the east and beheld a daunting obstacle: ‘Beyond stretched the barrier of the Alps.’ In those days, according to the tale, only Herakles had found a way through the Alps, and so they stood, ‘fenced in, as it were, by high mountains, looking everywhere for a path by which to transcend those peaks that were joined to the sky and so to enter a different sphere of the earth’ (‘in alium orbem terrarum’).

Described in these cosmic terms, the migration was a pilgrimage with no return, a mass enactment of the human journey from this world to the next. The Alps were to the Celts what the Red Sea was to the tribes of Israel. The answer came in the form of what the legend calls a sacred duty. Word reached the migrants that Greeks from Phocaea had landed at Massalia and were being attacked by local tribes called the Salyi. Seeing this as a sign of their own destiny, they went to the aid of the colonists and ‘enabled them to fortify the site where they had first landed’.

Having fulfilled their religious obligation, and reaffirmed their affinity with the Hellenic world, the Bituriges and their allies crossed the Alps by the pass of the Taurini (the Matrona) and the valley of the river Duria. Near the river Ticinus, they defeated the Tuscans and then settled in a country that belonged to a people called the Insubres. According to Livy, ‘Insubria’ was the name of a territory in the lands of the Aedui, which seemed a good omen, ‘and so the city they founded there was called Mediolanum’ (Milan).*

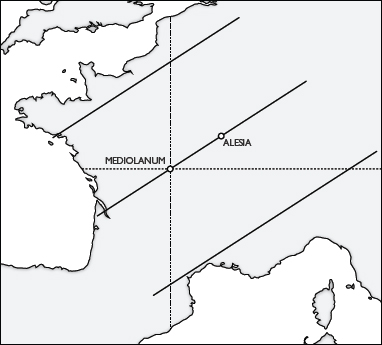

40. The pattern of migration

Livy goes on to describe the colonization of northern Italy by all the other Gaulish tribes that followed in the wheel-tracks of the Bituriges and their compatriots. First, by the same Alpine pass, came the Cenomani, then the Libui and the Saluvii. The next group, composed of Boii and Lingones, took a slightly different route, crossing the Alps by the Poenina (the Great St Bernard). Last of all came the Senones – presumably another contingent of the tribe that had joined the initial migration. Polybius gives a similar list, but he describes the Insubres as settlers rather than as the original inhabitants of Milan.

Most of this is historically true. North-eastern Italy was Celtic from the early fourth century until the Roman victory of 191 BC. Many settlements that became Roman towns were founded by Celts. Senigallia, on the Adriatic coast, preserves the name of the Senones, who also gave their name to Sens. Mezzomerico was once Mediomadrigo (from the Mothers of Middle Earth). Bologna, Brescia, Ivrea, Milan and Turin are all Celtic names. The Massalian episode probably dates from the same period. A century or so after the foundation of Massalia, when new trade routes were opening up along the Rhone, Massalian merchants would have sought the protection of tribes to the north. The most powerful trading port on the Gaulish Mediterranean would certainly have had to reckon with ‘the supreme power in Gaul’.

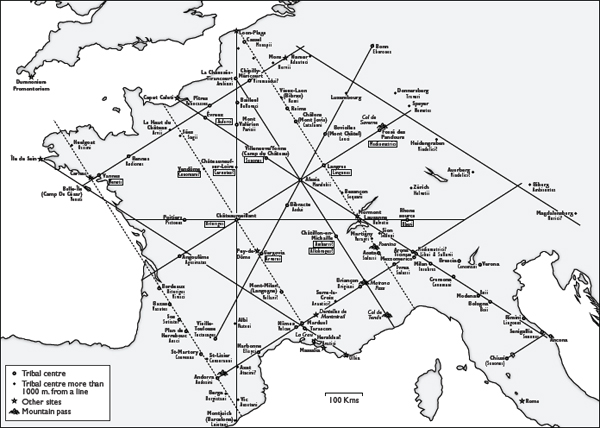

41. Tribal centres and the migration to Italy

The names in boxes are those of tribes who migrated to Italy. A solar line – sometimes more than one – passes directly through a Gaulish tribal centre in twenty-five cases and within 1000 metres of the site’s perimeter in twelve further cases (on average, 750 metres). In Italy, beyond Milan, the system suggests a general direction of migration rather than an exact trajectory.

Several minor oppida on the lines have been omitted (e.g. Les Baux-de-Provence, Mondeville by Caen, Malaucène, Vézénobres, etc.), as have tribes whose names or capitals are unknown (e.g. the Budenicenses and the inhabitants of Marduel and Tarusco). Some tribes or tribal names may differ from those of the fourth century BC.

Speculative journeys along the lines will reveal many other likely sites for which there is, at the time of writing, insufficient archaeological evidence (e.g. Dôle, Jouarre, Luxembourg, Montpellier, Najac, Treviso).

Bearings – taken where possible from the nodal points of Mediolanum Biturigum and Alesia – are those provided by the tangent ratio of 11:7 (57.53°, 122.47°, etc.), with the exception of the Alesia–Bibracte–Gergovia line, which, for geographical reasons, is 28.2° from north rather than 28.8° (see pp. 197–8).

The creation of a settlement obviously depended in part on topography, and so some leeway was presumably allowed. With a slightly broader margin, several more tribes could join the total of thirty-seven. Major oppida occurring more than 1000 metres from a line are indicated on the map: Arvii (1.5 km), Cenomani (1.5), Remi (at Bibrax) (1.7), Bergistani (2.4), Laietani (2.4), Atacini (3.1), Seduni (3.5), Ruteni (3.6), Consoranni (4.0), Atrebates (4.1), Morini (4.1), Nervii (4.1), Sagii (4.4), Ausetani (4.8), Osismi (4.8), Sequani (5.0), Veragri (5.0), Aduatuci (5.3). In retracing ancient surveys, especially over such long distances, common sense calls for certain adjustments. Future explorers of the system should feel free to experiment.

The legend is entirely plausible, except in one respect: the god-given itinerary looks very odd indeed. Unless Bellovesus and his followers mistook the lacy ridge of the Dentelles de Montmirail for a range of mountains, the territory of the Tricastini is a strange place from which to contemplate the distant Alps. Either they ignored the direction assigned to them by the Druids, or the gods’ instructions were exceedingly complicated: south-south-east, a deviation towards Massalia, then north-east, and finally south-east to New Mediolanum (fig. 40).

This all sounds like a post facto justification of military conquest, a boastful bardic tale designed to make the events fit a spurious divine plan. Yet Livy, like most ancient historians, accepted the divinatory basis of the expedition. Justinus, too, in describing the Celtic colonization of Italy and later migrations to the east, said – presuming that Druids used the same method as Roman augurs – that the Celts ‘penetrated into the remotest parts of Illyricum under the direction of a flight of birds, for the Gauls are skilled in augury beyond other nations’.

To a Druid, this hieroglyphic would have had the luminous logic of a work of art. What Livy and the other historians were unwittingly describing was a solar expedition reminiscent of Hannibal’s march through Iberia and Gaul. With the Druidic map as a guide, we can now retrace the exact route of the Celtic migration led by Bellovesus. The bisecting solstice line from Mediolanum Biturigum (the dotted line on fig. 41) leads past the great temple of Lugh on the Puy de Dôme (pp. 208–9) and across the stony plain of the Crau, where the enemies of Herakles were pelted with boulders from the sky. It ends at the bay of Massalia and the oppida by the inland sea of Mastromela which is now the Étang de Berre. (One of those oppida, Saint-Blaise, is considered the likeliest location of the lost city of Heraklea near the mouth of the Rhone, which had disappeared by the time Pliny heard of it in the first century AD.) (See the map on p. 154.)

The Mediolanum line meets the Aquitanian–Armorican line (p. 146) at a point marked on ancient itineraries as ‘Trajectus Rhodani’. Here, at the meeting of roads from Mastromela and the Matrona, was one of the major crossings of the Rhone, where Tarusco (Tarascon) looks over to the oppidum of Ugernum (Beaucaire). In the Middle Ages, Beaucaire was the site of the biggest international fair in Europe, and it was already a trading hub in the fifth century BC, when wine amphorae were arriving from Massalia and Greece. Herakles himself had been there: ‘Tarusco’ recalls the name of the monster Tauriscus who, according to the Druids’ account of Gaulish origins, was defeated by Herakles on his march through Keltika. The line then continues to the bay of Olbia (Hyères), a trading port founded by Massaliots in the fourth century BC.

Here again, we pick up the trail of the migrants. Olbia is mentioned in a different context by Strabo as one of four Massaliot cities that were ‘fortified against the tribe of the Sallyes and the Ligures who live in the Alps’. The Sallyes are the same as the Salyi, the troublesome tribe that was defeated by the followers of Bellovesus when they came to the aid of the Greek colonists. Olbia was closely linked with a native oppidum on the neighbouring hill, and the excavator of Olbia suggests that in defending themselves against the attacks of Ligurians, the Massaliots cooperated with Celtic tribes who had settled on the coast.

It now appears that when the Bituriges and their compatriots contemplated the distant Alps from the territory of the Tricastini, they were looking through the eyes of the sun god. On their solar path to the lands of the Salyi and the Massaliots, they would have crossed the river Gard just downstream of the ford where the Roman aqueduct, the Pont-du-Gard, still stands. At that exact spot, they found themselves for the first time on the Via Heraklea. The point of intersection is marked by the oppidum of an unknown tribe. Its crumbling masonry, on the Marduel hill opposite Remoulins, is the oldest known urban enclosure in eastern Languedoc (c. 525 BC). This was one of the three most important towns of the region. It stood at the meeting of two major roads and guarded the ford.

Fording the river, the travellers turned onto the Via Heraklea and climbed towards the limestone hills. The Heraklean line passes three small oppida* and then the Dentelles de Montmirail as it heads for the Alps. Since the only way through the mountains was the col forged by Herakles, the migrants would naturally have taken his solstice route across ‘the pass of the Taurini’. This is the pass more commonly known as the Matrona or Montgenèvre. After entering Italy through this Heraklean gateway, they would have followed the river Duria (the Dora), which flows from the Matrona and alongside the Heraklean line to Arona, the cultural crossroads of Iron Age Gaul, Switzerland and Italy (p. 145).

Picking up the winter solstice line from Alesia, they then travelled south-east to the point at which the river Ticinus (the Ticino) leaves Lake Maggiore. Somewhere near that river (the site is unspecified), the migrants defeated the Tuscans. The battle is thought to have taken place in the river basin between Castelletto sopra Ticino and Golasecca. Both places stand on the solstice line.

The journey of the first contingent of pioneers is almost over: the Alesia line – a long cord attached to the mother-city of the Celts – at last leads directly to the Mediolanum which is now the city of Milan.

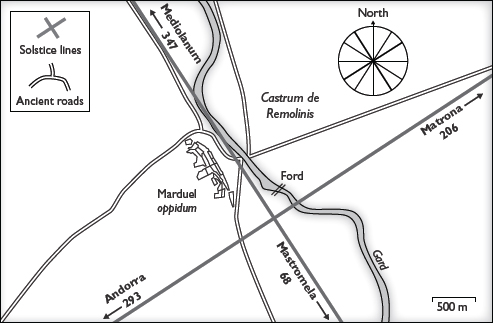

42. Solstice lines at the Marduel oppidum

Distances from the intersection are given in kilometres.

A few weeks or several years later, the reliability of the system having been tested and proved, other tribes follow the same Druidic route-map, pushing further into north-eastern Italy and founding Celtic towns along the route of what became the Via Aemilia. ‘South of the Padus, in the Apennine district, beginning from the west, the Ananes [an unknown tribe] and then the Boii settled. Next to them, on the coast of the Adriatic, the Lingones, and south of them, still on the sea-coast, the Senones’ (Polybius). The Libui and the Saluvii settle in the vicinity of the Ticinus near the site of the battle (Livy).

The Lingones, whose Gaulish capital stands on the line from Alesia, seem to have been offered a shortcut by the Druid augurs. The account recorded by Livy says that the Lingones crossed the Alps by the Poenina, which is now the Great St Bernard. Since the Poenina was impassable for wheeled vehicles (according to Strabo), one of Livy’s editors suggests that this was a mistake for the Matrona, but the map of Middle Earth shows that a crossing by the Great St Bernard, though arduous for humans, would have been perfectly acceptable to the gods: for the Lingones, as for the Remi and the Catalauni, the most direct solar route to the Heraklean Way passes over the Great St Bernard.

The final episode of the great migration, reported by Diodorus, involved the Senones, who came from the area of Sens, a hundred kilometres south of Paris. For some reason, the Senones had been assigned the territory furthest from the Alps. Coming as they did from the chillier part of Burgundy, they found the Adriatic intolerable: ‘Because the region was scorching hot, they were distressed and eager to move, and so they armed their younger men and sent them out to seek a land where they might settle.’ Several thousand young Senonians then marched off to Clusium (Chiusi).

Meteorologically, it was a bizarre choice by the sweltering Senones: Clusium lies more than half a degree of latitude to the south, but it also lies on a solstice line that reaches the coast directly between the two Senonian settlements of Ancona and Senigallia. From Clusium, the young Senones set off for Rome.

This took place in 387 BC, about ten years after the likely date of departure from Mediolanum Biturigum. Perhaps the silent procession of Celtic warriors into Rome, along the streets lined with old bearded noblemen, had been part of the original plan, just as Delphi was the target of one of the later groups (pp. 171–3). For the Romans, the invasion was a punitive raid provoked by the killing of a Gaulish chieftain at Clusium by a Roman ambassador. But from the vantage-point of the Druids and the sun god, Rome was a logical terminus of the labyrinthine route. Diviciacus may have known this when he stayed there with Cicero in 63 BC: the winter solstice line from Mediolanum Biturigum, with an imperceptible variation of eight-hundredths of a degree or 1/4500 of a circle, leads to the Palatine Hill. To be absolutely precise, it leads to the site of the future Vatican City.

The precision of the Druidic system is quite amazing. The capitals of the tribes that took part in the great migration appear as though by magic on the grid of solstice lines: the Aedui, the Arverni, the Aulerci, the Bituriges (represented by Mediolanum Biturigum), the Lingones and the Senones. Not all the pre-Roman capitals are known, but the oppidum of Vindocinum (Vendôme) on the Mediolanum Biturigum line and the oppidum-like site of Châteauneuf-sur-Loire on the meridian might now be considered possible early tribal centres of the Cenomani and the Carnutes.*

The weirdly accurate projection of the upper world onto Middle Earth confirms what several historians have suspected: that many tribes other than those mentioned by Livy and Polybius took part in the migration. No fewer than thirty-seven tribal centres occur on the lines, which implies a coordination of the population on a huge scale. Some of those tribes may have joined their neighbours or assisted the migrants who passed through their territories. The Ambiani or their fourth-century predecessors, for instance – whom Livy may have confused with the Ambarri – clearly belong to the same network: the bisecting solstice line from Alesia passes within a few metres of the thatched Gaulish house at Parc Samara and leads exactly to the western entrance of the oppidum.

This beautifully choreographed diaspora is a stunning example of the Druids’ belief in ‘the power and majesty of the immortal gods’ (p. 131). First came the myth, and then, by a deliberate process of religious and scientific observance, the reality. It proves that the migration legend was not a retrospective fantasy, a heroic tale told after the event. The legend was a faithful record of the original plan. This is not such an unusual pattern of collective behaviour: wars and migrations are often inspired by myths and national legends. But the sheer scope and accuracy of the Celtic enterprise are unparalleled.

Until now, it has been impossible to show exactly how divinatory calculations determined historical events. The Druids who directed the tribes were not fraudulent conjurers who made a nation’s destiny depend on the twitch of an entrail or the parabola of a bird’s flight. They were the coordinators of an immense work of art that was one of the most ingenious and effective federal systems ever devised. It gave the tribes a view of Middle Earth that had once been the prerogative of the gods and that would not be seen again by earth-bound mortals until the cartographic marvels of the Renaissance.

The standing stones of ‘Celtic’ Brittany, which belong to a much earlier civilization, represent a more localized form of organization. At Carnac, prehistoric menhirs march towards the solstice sun in approximately aligned avenues hundreds of metres long. But the Druidic alignments were something quite different from those lumbering, labour-intensive sun-paths. Though some sections of the lines, like parts of the Via Heraklea, would eventually be materialized as roads (p. 205), they existed primarily as intellectual abstractions, created by mind instead of muscle. They were the avenues and henges of a new age in which science and technology were the means of discovering the designs of the living gods.

‘Hi terrae mundique magnitudinem et formam, motus caeli ac siderum et quid dii velint, scire profitentur.’* Under the scientific direction of the Druids, history became the visible expression of the gods’ will. But the will of the gods is not identical with the desires of human beings. The coordinated colonization of northern Italy and the capture of Rome – the city that lay at the end of the winter solstice line from Mediolanum Biturigum – were the catalysts that stimulated the expansion of a Roman empire. Perhaps the Druid augurs knew that, some time in the distant future, Alesia the mother-city would be the site of a great battle. They believed that one day, the sky would fall and the earth be destroyed by fire and water. When they brought the heavens down to earth, they made the Celts the servants of the gods and the agents of their own destruction.

* On the location of this ‘consecrated place’ mentioned by Caesar, see pp. 316–17.

* These and other lines are illustrated on the large map on p. 154.

* If so, the line would be slightly closer to Châteaumeillant than Châteaumeillant is to Belvianes: since klimata or lines of latitude are based on length of day rather than distance on the ground, the lines become increasingly crowded as they approach the poles, which is one reason why the theory of equidistant Mediolana would never have revealed a pattern.

Except where stated, the assumed tolerance is less than ten seconds of day length (even measuring the length of day to the nearest minute would have been a remarkable achievement). The bearings are precisely accurate. Far less rigorous criteria are normally applied to the tangents of Roman roads and to the orientation of towns and temples.

* Two further coincidences on this Aquitanian and Armorican line, apart from those mentioned later (p. 156): 1. The point south of Alesia from which the line is projected lies just outside the village of Bezouce (Gard), which is thought to have been the capital of a tribe, the Budenicenses, whose existence is attested only by two inscriptions. 2. The point of intersection with the Alesia line lies a few hundred metres from the castle of La Rochefoucauld – a possible oppidum site and the home, in the tenth century AD, of a man said to be a son of the Fairy Mélusine, who was also present at Châteaumeillant. (But Mélusine was an exceptionally well-travelled fairy.)

* See the note on portolan charts, p. 303.

* The date set by the Helvetii for their migration was around the time of the spring equinox, when the sun sets due west – the direction in which they intended to travel. Heading west from their assembly point, Geneva, they would indeed have reached the lands of the Santones, just to the north of La Rochelle.

* Tarquinius Priscus was on the throne at the time when Massalia was founded (c. 600 BC), but the legend conflates different periods. The Etruscan city of Melpum, on the site of the future Mediolanum (Milan), was destroyed in 396 BC, and the Celts entered Rome in 387 BC. The Biturigan hegemony probably dates from the fourth century BC.

* ‘Tricastinis redditi’: (lands) restored to the Tricastini.

* For these and the following sites, see the large map on p. 154.

* Les Courens (Beaumes-de-Venise), Saint-Christophe (Lafare), le Clairier (Malaucène).

* Five other tribes can be added to the partial lists supplied by Livy. The Salassi from Aosta settled at Eporedia (Ivrea). The Insubres or Insubri are named as settlers by Polybius: the first part of ‘Insubri’ means ‘path’ or ‘direction’; the second suggests an offshoot of the Uberi who lived at the source of the Rhone and the Pillar of the Sun on the equinoctial line from Mediolanum Biturigum. The Mediomatrici gave their name to Mezzomerico. The Allobroges are mentioned in this connection by Geoffrey of Monmouth. The Veneti were said by Claudius to have invaded Rome with the Insubres.

* ‘They profess to know the size and shape of the earth and the universe, the motion of the sky and the stars, and what the gods want’ (p. 131).