We left Segovesus and his band of migrants marching glumly towards the enormous Hercynian Forest. While the tribes led by his brother Bellovesus were basking in the vineyards of northern Italy, a more obscure but even grander odyssey was under way. It covered such a vast area that the Druidic calculations were inevitably less precise. Yet the trajectories of this other mass migration show the same adherence to the sun’s course, even two hours of daylight east of Mediolanum Biturigum, to the centre of the classical world and the shores of another continent.

The name of the Hercynian Forest, first recorded by Aristotle in 350 BC, is Celtic – ‘Ercunia’, or, in the very old days, before the language had changed, ‘Perkwunia’, meaning ‘oak’. The other word for ‘oak’ was ‘dru-’, as in ‘Druid’. Ancient Celtic seems not to have distinguished different species of quercus, and so the two words must have referred to the tree in different guises. The Ercunian was the wild, uncultivated oak, the centenarian giant that had never spread its lattice shade in a Druid’s grove and whose acorns fed animals that had never seen a human being. Its domain was larger than an empire. The breadth of the forest, Caesar learned, was nine days for someone travelling without baggage, but its length was a matter of conjecture – sixty days, according to Pomponius Mela, more if Caesar’s information was correct. The forest began in the lands of the Nemetes, the Helvetii and the Rauraci who lived along the Rhine. Some people from that part of Germania had trekked through the tangled gloom for sixty days but had never reached the other side, nor even found a creature who could tell them where it ended.

‘Impervious to the passage of time’, the Hercynian Forest was thought to be as old as the world itself. Remnants of what was once the largest natural feature in Europe survive in patches of woodland and forest. The town of Pforzheim, which is now the northern gateway to the Black Forest, was once Porta Hercyniae. Some of the migrants led by Segovesus would have passed through the Bavarian or Bohemian Forest which marks the borders of Germany, Austria and the Czech Republic. The names, ‘Bavaria’ and ‘Bohemia’, are mementos of the restless Boii tribe, who took part in so many Celtic migrations that no one knew for sure – perhaps not even the Boii themselves – where their homeland had been.

The forest followed the north bank of the Danube, and then, in the lands of the Dacians, near the western edge of the Carpathian mountains, it ‘turned left’, according to Caesar’s information, away from the river. It stretched so far that it ‘[touched] the fines [‘territories’ or ‘borders’] of a great many nations’. (The word ‘fines’ suggests that, like other forests, it served as a buffer between tribal groups.) There is only one other shred of evidence: a tribe that settled near the bend of the Danube in the Roman province of Pannonia (western Hungary) was called the Hercuniates. The ‘Folk of the Hercynian Forest’ are described by Pliny and Ptolemy as a ‘civitas peregrina’, a wandering tribe that had come from foreign parts. Three sites have been identified as oppida of the Hercuniates in the region of Lake Balaton, but it would be as hard to retrace their footsteps through the forest as it is for an archaeologist to distinguish an Iron Age settlement from mounds raised by fallen trees and rocks assembled by their clawing roots.

Into this sunless expanse the Druids sent Segovesus and his followers, condemning them and their descendants to a diet of berries and beer. Sailors adrift on the ocean are surrounded by clues to their whereabouts; a traveller in a forest the size of half a world is confined to small dark spaces that endlessly recur like the scene of a nightmare. The guiding stars are eclipsed by branches and blurred by the breath of the forest. A stranger in Hercynia could navigate only by the soft cloak of mosses on the north face of oak trunks and by the diffuse glow of the dawn. Sometimes, there was a hill from which to take a sighting, or a moonlit clearing where sawn trunks showed where hunters had tried to catch the jointless elk. According to Caesar, there were ‘vague and secret paths’ through the forest, but Pomponius Mela described it as ‘invia’ (‘trackless’). Beyond the Rhine, the solar route-map seems to be of little help, though it is hard to believe that the Biturigan Druids sent a royal prince and thousands of migrants blundering off into totally uncharted territory.

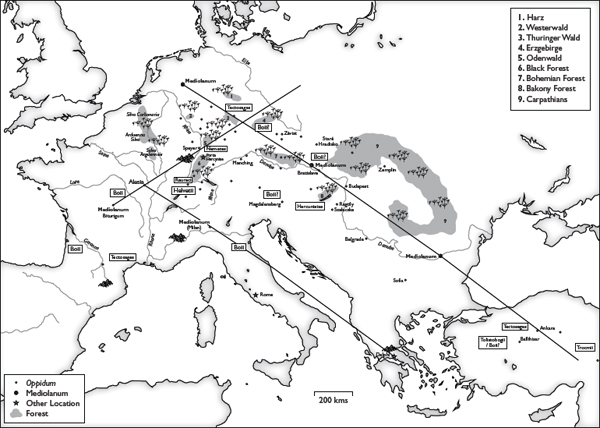

From Mediolanum Biturigum, the solar direction assigned to Segovesus would have taken him to the east-north-east. Recounting the same legend, Plutarch says that a group consisting of ‘many myriads of warriors and a still greater number of women and children’ ‘crossed the Rhipaean mountains, streamed off towards the Northern Ocean, and occupied the remotest parts of Europe’. The mythical Rhipaean range lay somewhere to the north in whichever inhospitable clime ancient writers chose to place it. The crucial detail is that Segovesus, like his brother, crossed a range of mountains. The east-north-easterly solstice line from Mediolanum would have taken him to Alesia and across the Vosges by the pass of the Mediomatrici, mirroring Bellovesus’s crossing of the Matrona. From there, it was a short distance to the land of the Nemetes (‘The People of the Sky Sanctuary’), who, in Caesar’s day, lived on the western edge of the forest. (These routes are shown in fig. 43.)

The Mediolanum–Alesia solstice line passes within five kilometres of Speyer (the Roman Noviomagus Nemetum). Crossing the Rhine, the migrants would then have entered the Odenwald south of Heidelberg. Unless they journeyed on to the north and vanished into parts of Europe that were never Celtic, they would have turned to face the rising sun of the winter solstice: the line that runs exactly one hour of daylight to the north of the Alesia line passes through the Bohemian Forest. After an age that was only a short time in legend and the life of the forest, a group of migrants led by a descendant of Segovesus arrived at the place which is now the capital of Slovakia. In the second century BC, on the hill where Bratislava Castle looks down on the Danube, an oppidum was built by the wandering tribe of Boii who had already colonized part of northern Italy.

This far to the east, where the Danube begins to leave the trackless forest for the Great Hungarian Plain, there is only the faintest hope of finding any solar evidence of tribal movements. The earlier system of Mediolana, from which the Druidic system evolved, was almost exclusively Gaulish. Before the period of expansion, ‘Middle Earth’ may have been conceived of as the part of the European isthmus bounded by the Alps, the Pyrenees, the Mediterranean and the Atlantic. This was the Gaulish homeland of well-ordered rivers and mountains which Strabo described in a passage that seems to echo a lost Celtic legend: ‘The harmonious arrangement of the country appears to offer evidence of the workings of Providence, since the regions are laid out, not haphazardly, but as though in accordance with some calculated plan.’ Beyond Gaul, there are just a few outlying Mediolana, some separated from the others by hundreds of kilometres. The northernmost of these latter-day Mediolana is Metelen near the Dutch-German border. In all of Europe east of Switzerland, only two Mediolana are known: the town of Wolkersdorf north of Vienna, and a staging post near Ruse in Bulgaria on the Romanian border. To find traces of the Celtic network of ‘sacred centres’ in the Hercynian Forest and beyond is surprising. To find three of those rare sites on the same Hercynian trajectory is entirely unexpected.*

The forest tribes, Caesar learned, ‘know nothing of road measurements’. But measurement on the ground would have been useless in a trackless forest, and even if someone had spent sixty days walking through Hercynia, journey times over natural terrain were a crude gauge of distance. The only practical way for Celtic tribes who lived on either side of the forest to obtain some measure of its expanse was geodetic. Bratislava lies sixty longitudinal minutes east of Mediolanum Biturigum; nine latitudinal minutes is about one hundred kilometres, which might have been the breadth of the forest at its narrowest point. (It seems astonishingly appropriate that the reported dimensions of the forest – nine days wide and sixty days long – correspond so closely to the geodetic measurements: Roman writers may have understood these numbers to refer to days of human travel rather than to the timetable of a sun-chariot.) By whichever paths they reached their destination, the Celts who settled on the hill which is now a part of Budapest had the means of knowing that the length of their longest day was practically the same as at Alesia, and that their oppidum lay on a solstice line from Bratislava and the Bohemian Forest.

43. Oppida east of Gaul and remnants of the Hercynian Forest

The Hercuniates might have reached their new home (the oppida around Lake Balaton) by travelling due east along the equinoctial line from Mediolanum Biturigum, via the capital of the Helvetii and the sources of the Rhone and the Rhine.

The leaves and branches that fall in a broadleaf wood quickly form a thick blanket under which forest creatures sleep through the winter and which gradually turns into the heavy earth of a sepulture from which nothing will awake. A few isolated coordinates are of little more value than coins that have worn smooth. Almost everything to do with the Hercynian Forest is either impenetrable or implausible – the giant oaks engaged in wrestling contests that lasted centuries; the bovine urus, slightly smaller than an elephant, that raced through the trees at tremendous speed; the Hercynian bird whose feathers glowed in the night like fires. The Mediolana that seem to mark a migration route through the forest may each have been part of a local system, or they may simply have been named after places in tales that were told about the homeland in the west. The names of the trans-sylvanian Celtic tribes were eventually recorded when the lands they had colonized became the Roman provinces of Noricum, Pannonia, Dacia, Moesia and Galatia, but the tribes had moved so frequently and so far, intermarrying, dying out and re-emigrating, that sometimes even the direction of the original migration is in doubt.

The history of the Celtic diaspora of the fourth to second centuries BC is a long and twisted tale of invasions and expulsions, settlements and extinctions. It should make even the most ardent Celtic supremacist despair of ever identifying any fundamental ethnic trait of Homo celticus. Some tribes adopted local customs so completely that by the time they became known to the Romans, their only clearly Celtic feature was their name. Mercenaries went to work in distant lands accompanied by their wives and children. The Galatians of Asia Minor – the ‘foolish’ recreants of St Paul’s epistle – owed their name to Celtic immigrants from Gaul. Several hundred of their finest warriors served as Cleopatra’s bodyguard. Later, the same elite troops were employed by Herod the Great. The infant who was to become King of the Jews might have been beheaded in Bethlehem by a Celtic sword.

Woven in amongst these grand and ragged tales of tribes ranging over a continent are all the microscopic mysteries of trade, the interminable journeys of trinkets and treasures carried by merchants or passed from hand to hand, stolen, sold or copied. Every museum that has a Celtic collection is a trove of insoluble enigmas. How the silver Gundestrup Cauldron ended up in a Danish peat bog somewhere near the northern Pillars of Hercules, no one knows. (The metalwork suggests that it was manufactured in the region of Bulgaria, but was it commissioned by natives of the ‘outermost islands’ or brought back from the east by the ‘Germanic’ tribes, the Cimbri and Teutones, whose kings had Celtic names?) Whole chapters of a civilization’s history lie undeciphered in cabinets and coin drawers. As they moved across the Continent like a herd of sacred transhumant animals, the sun-horses of Celtic coins morphed and evolved. If a historian of ancient art could devise an equation of shapes and curves and zoomorphic astronomy, it might be possible to retrace the movements and filiations of the tribes, and to recover some of the myths that are encoded in those quaint and lovely creatures.

44. Horses depicted on Celtic coins and their approximate geographical origins

Most of these coins date from the first century BC.

Just as the flocks of birds passing over the ocean of trees followed their own unvarying solar routes, a general trend is perceptible in the wanderings of Celtic migrants. Young men went east in search of treasure and adventure – some to the north-east, many more to the south-east. With the late exception of the Helvetii’s foiled migration (pp. 149–50), westward movements were either a return to the homeland or the result of disaster: the Celts who had come to Gaul from beyond the Rhine, according to the Druids, had been ‘driven from their homes by frequent wars and inundations of the fiery seas’. Only the defeated and the exiled walked towards the dying sun with their shadows tarrying behind. There is no good evidence that the westernmost regions by the Atlantic were invaded and settled by Gaulish tribes in this period, and the question to be asked about the Celtic inhabitants of Ireland and the Iberian Peninsula is not, ‘Where did they come from?’, but ‘When did they become Celtic?’

The ‘vague and secret paths’ along which even Caesar refused to send his legions when ‘the woods closed over the fleeing enemy’ will never be known, but sometimes, in the chronicles of classical writers, there are signposts and even pieces of map. One journey in particular is sufficiently well documented to show where the migrants entered the forest and where they left it. Along with the capture of Rome in 387 BC, it was the most daring of all the Gaulish odysseys. The tribes would talk about it for centuries to come, and when the bards sang their long tales of the great adventure, the descendants of Bellovesus and Segovesus would have seen, as though from one of the great hill forts of Bohemia towering over the forest, a comprehensive vision of the wide world beyond the tidy shires of Gaulish Middle Earth.

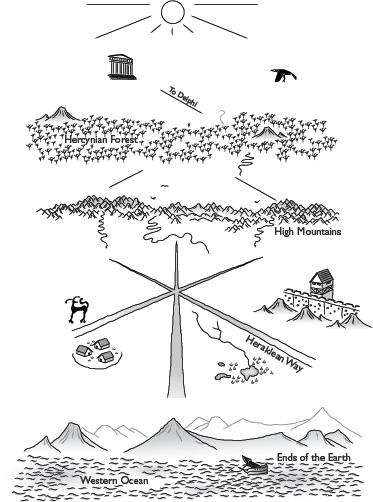

45. The expedition to Delphi. (East is at the top.)

‘In days gone by’, said Caesar, a sub-tribe of the Volcae called the Tectosages (‘Wealth-Seekers’), ‘because of the great number of their population and the insufficiency of their farmland, had sent colonies across the Rhine. They took possession of the most fertile parts of Germany around the Hercynian Forest and there they settled.’ This is almost certainly a fragment of the Biturigan migration legend: the Tectosages had come from the region of Toulouse in south-western Gaul. It had been a long trek from Aquitania to the Rhine, but soon the tribe was stirred again by the old restlessness. In the early third century BC, another contingent of ‘Wealth-Seekers’ left for the east with two other tribes: the Trocmii, whose origins are unknown, and the Tolistobo(g)ii, who were probably a branch of the ubiquitous Boii.

Following the winter solstice trajectory through the Hercynian Forest, they would have reached its eastern edge near the shores of the Black Sea. Here, they entered a world in which historical events were recorded in writing, and so they can be seen, as it were, in the open, no longer hidden by the trees, crossing the Hellespont in 278 BC and colonizing the land that came to be known as Galatia. The Tectosages eventually settled at Ancyra (Ankara). Each of the three tribes was divided into four sub-tribes, and the twelve tetrarchs held their annual council at a place called Drunemeton (‘Sanctuary of the Oak’). Coins of the Tectosages from the region of Toulouse, almost three thousand kilometres to the west, seem to represent the same political system – a cross, with a symbol of wealth or authority in each of its quadrants: a crescent moon, a nest of stars, an ellipse, sometimes a sheaf of wheat and almost always an axe.

To the people whose lands they ravaged, the itinerant Celts were an appalling horde of semi-human drunkards. Some of the Tectosages butchered their way down the eastern Adriatic. According to the Greek geographer Pausanias, they raped the dead and the dying, and selected the plumpest babies for their feasts. Pushing on through Macedonia, they crossed the river Spercheios. Some used their shields as rafts; others simply waded across – because, said Pausanias, the Celts are ‘far taller than any other people’. As the Greek cities assembled their armies, it was becoming apparent that this chaotic rampage had a goal. The horde reached Heraclea, but instead of attacking the town, it battled on towards the pass of Thermopylae.

Beyond Thermopylae lay the fabled land of wine and wisdom where the sun god returned to the earth. The horde knew exactly where it was and why it had come there. The leader of the expedition to Rome in 387 BC had been a warrior called Brennos; the leader of the Greek expedition in 279 BC was another Brennos – from ‘branos’, the Celtic word for ‘crow’. The two expeditions, a century apart, were astronomically symmetrical. Rome lay on the solstice line from Mediolanum Biturigum; the goal of the later expedition – Delphi – lay on the solstice line from Alesia.* A day’s march from Thermopylae, white temples stood on the slopes of Mount Parnassus. There, the Massaliots, along with many other Greek cities, had their treasury, filled with statues and other offerings to the gods, because it was in the place called Delphi (‘womb’) that the two eagles or crows released by Zeus had met and defined the centre of the world.

The battle tactics of the Celts seemed so ridiculously suicidal to Pausanias that he assumed that they had no seers or priests to advise them. At Thermopylae, the sun rose and the barbarians rushed into the pass. A heavy fog was rolling down the mountains, and the Greeks were waiting. Thousands of Celts were massacred in the gullies or trampled into the marshes of the floodplain, yet the survivors struggled on ‘without even begging leave to recover their comrades’ bodies, caring not whether they were buried in the earth or devoured by wild animals and birds of prey’. The original source used by Pausanias evidently had some knowledge of Celtic religion: at Thermopylae, the souls of the Celtic dead would travel to the upper world or to the lower. Perhaps they knew that the hot springs of Thermopylae had been created by Herakles when he had tried to quench the fire of the Hydra’s poison, and that its sulphurous caverns led directly to the underworld.

For the Greeks, what happened at Delphi in 279 BC was an inconceivable calamity: the hinged wings of an iron crow flapping on his helmet, a Celtic chieftain rummaged through Apollo’s sanctuary. The Cyrenean poet Callimachus wrote of the invasion only a few years after the event in his Hymn to Delos:

Latter-day Titans shall raise up against the Hellenes

A barbarian sword and the Celtic god of war,

Rushing from the extreme west like snowflakes,

Or as numerous as stars when their flocks are thickest in the air.

In Greek accounts, the disaster at Delphi has two different endings. Some say that the Celts looted the sanctuary and stole its treasures. Others softened the blow to Greek pride by imagining a miraculous intervention: the gods overwhelmed the barbarians with thunder and lightning, an earthquake, a snowstorm that caused a landslide, and a mass hallucination that made them think that their comrades were speaking Greek. They stabbed one another to death and their leader Brennos committed suicide by drinking undiluted wine.

No material evidence has been found of any destruction at Delphi in 279 BC, either by Celts or by earthquake. A raid of some sort took place, but it is unlikely that Delphi had been chosen for its treasures: there were far more lucrative and accessible places to plunder. This cruel and costly expedition to the centre of the world had a symbolic, religious aspect: it was a heroic episode in a national epic acted out by an army of belligerent, wine-drinking pilgrims. Both Callimachus and Pausanias significantly describe ‘the mindless tribe of Galatians’, not as eastern neighbours of the Greeks, but as people from the other end of the earth – ‘the barbarians who came from the Ocean’ or ‘from the extreme west’. The logic of Celtic geography is unmistakable: the Tectosages had journeyed from the sunset to the sunrise on the paths of the sun god. Their leader, Brennos, personified the crow, which in Irish mythology is associated with the god Lugh. When he stood at the omphalos of the world, taking into his body the concentrated nectar of the sun, this was not the mortification of a drunken soldier, but a ceremony of sacrifice and communion.

For the Celts, Delphi was not the end of the story, but the rest of the world found out what had happened to the Delphic treasure only many years after the expedition, when the Tectosages of Gaul had become vassals of Rome. The crow had sailed back over the forest to its home near the Ocean, as though the odyssey would reach its conclusion only when the circle or ellipse was complete. A sanctuary that became the chief oppidum of the Tectosages stood above the river Garonne to the south of Tolosa (Toulouse). There, the survivors of the expedition told tales of the endless forest and the sunny lands beyond. Some may have proudly displayed a Greek helmet, a Carpathian bride or the severed head of a German preserved in cedar oil.

As for the treasure, it was considered the property of the gods, and disposed of accordingly. Posidonius, who travelled in southern Gaul in the early first century BC, learned that it was worth about fifteen thousand talents and consisted of unwrought gold and silver bullion. Bars of solid silver had been melted and hammered into the size and shape of mill-stones, and placed where the ‘frugal, god-fearing’ Celts traditionally stowed their riches:

It was the lakes, above all, that gave the treasures their inviolability, and into them, the people let down heavy masses of silver or even gold. . . . In Tolosa, the temple, too, was hallowed, since it was much revered by the inhabitants of the region, and for this reason, the treasures there were excessive, for many people had dedicated them to the gods and no one dared lay hands on them.

Posidonius was describing the practice known as ritual deposition. Such enormous quantities of precious metals were consecrated to gods of the underworld and deposited in wells, pits, rivers and lakes that the archaeological record shows a scarcity of Gaulish gold towards the end of the Iron Age. Though the Tectosages all knew where the treasure was hidden, it remained untouched until the Roman conquest of southern Gaul: in 106 BC, a Roman proconsul, Quintus Servilius Caepio, drained the lakes and made off with the bullion. Terrible punishments had traditionally been meted out to anyone who tampered with public treasure. Since Caepio was a powerful Roman, his punishment had to be left to the gods. According to a legend reported by Timagenes, Caepio was sent into exile and all his daughters became prostitutes.

It is unlikely that the cursed Caepio discovered the true Delphic treasure: the shrines of Delphi were not repositories of gold and silver bullion; most precious metal in the region of the Tectosages came from their mines in the foothills of the Pyrenees. Whatever its form and origin, the true value of the treasure was symbolic. The Tectosages had travelled to the centre of the world, taken the gold of the sun from its place of birth, and buried it in their homeland in the extreme west. The ritual of deposition may have resembled Egyptian burials of the mummified sun god. The details escape us completely. But we do know that the expedition forged a geographical and sacred link between the centre of the Greek world and the Western Ocean.

‘Many large rivers flow through Gaul, and their streams cut this way and that through the level plain, some of them flowing from bottomless lakes and others having their sources and affluents in the mountains, and some of them empty into the ocean and others into our sea.’ Diodorus, like Strabo, seems to have acquired some accidental knowledge of the complicated three-dimensional geometry of the Celtic universe. Perhaps there was a mythical underground river that encircled the earth and allowed the sun god to travel back to his place of birth; perhaps the river was the Ocean itself, which, as Pytheas the Massaliot had discovered, eventually merged with the sky. But beyond the landscaped symmetries of Middle Earth, the universe of the ancient Celts is as mysterious as the Hercynian Forest.

The physical treasure itself may be easier to recover than the lost Celtic myths. The word used by Posidonius in describing its hiding places is limnai, the plural of limne, meaning a marsh, a pond or a shallow lake, ‘a pool of standing water left by the sea or a river’. Some elderly Toulousains, interviewed in the 1950s, remembered swimming in shallow ponds which appeared along the ancient course of the river in the Pont des Demoiselles quartier in the south-east of Toulouse. Nothing of value was ever found there, and although gold, jewels, torcs and armbands from the Lower Danube have been discovered in the former lands of the Tectosages, none of them can be traced as far as Greece.

No doubt these were the ponds that were drained by the greedy proconsul. Posidonius says that the limnai were ‘in Tolosa’, but there were other marshy places, outside the Roman city, closer to the pre-Roman home of the Tectosages. The oppidum above the river at Vieille-Toulouse has wide views to the south-west, over the ponds of what is now the Parc du Confluent. Here, the Garonne, which flows to the Atlantic, is joined by the Ariège, which rushes down from the mountain pass where the Heraklean Way crosses the Pyrenees. River confluences are classic sites of ritual deposition. The quiet little patch of woodland by the confluence, criss-crossed by signposted paths, may once have been a holy place. A treasure might have been unknowingly extracted from the gravel pits and dumped on a driveway or a path, but since even a heavy object, rolling on a bed of pebbles, urged by the conjoined force of two rivers, will travel many metres in a year, a sacred relic from the centre of the earth may at last have completed its long journey to the Ocean at the end of the world.

* The bearing from Metelen to Wolkersdorf is within 0.15° of the Gaulish standard (122.32°). The bearing from Wolkersdorf to Ruse, despite the great distance, is accurate to within one point of a 128-point compass (124.74°). Medieval portolan charts used a 32-point compass.

* Within one point of a 128-point compass (124.62°). See p. 165n.