In the autumn of 57 BC, fifty-three thousand men, women and children, comprising the entire surviving population of the Aduatuci tribe, were crammed into a small oppidum in what is now southern Belgium. The exact site is unknown – it might have been the citadel of Namur – but the number is certainly accurate since it was given to Caesar by the traders who bought the Aduatuci as slaves. The Gallic War was nearing the end of its second year, and it was already proving astonishingly lucrative. In only a few months of campaigning, the Romans had driven the Helvetii and their allies back to their homelands – reducing their population by about two-thirds – and conquered practically every northern tribe between the Rhine and the Atlantic. That autumn, Caesar reported to the Senate that ‘all of Gaul has been pacified’. When he came to write up his annual reports for his Commentaries on the Gallic War, he would be able to add a triumphant postscript to Book Two: ‘Upon receipt of Caesar’s letters, fifteen days of thanksgiving were decreed, which had never happened before.’

Roman businessmen might have feared that Gaul would be a logistical nightmare, but they had every reason to be delighted with the Gaulish infrastructure. The land of the Druids had been turned into an enormous emporium and distribution centre. Huge quantities of booty and endless caravans of human merchandise headed for Rome, while horses, provisions, naval armaments and other military equipment flooded into northern Gaul from Italy, Spain and the province of Gallia Transalpina. Compared to the intense activity of the private companies with contracts to supply the Roman army, fighting took up only a small part of the war: between 58 and 51 BC, there were fewer than four battles a year. On a map, the itineraries of the legions look like a tangle, but through the eyes of an import-export manager, the commercial rationale of the Roman campaigns is obvious. In the more prosaic passages of his Commentaries, Caesar himself sometimes makes the business plan explicit. While the fifty-three thousand Aduatuci were being marched off towards Italy, the Twelfth Legion was sent to guard the Upper Rhone in order to liberate Roman traders from ‘the very great dangers and very great customs duties’ that had hampered them in the past.

By the end of 57 BC, the Gallic War was practically over. Most of the remaining six years were devoted to mopping-up operations, the quelling of revolts and the installation of puppet kings and tribal governments friendly to the Romans. In 55 and 54 BC, Gaul was still sufficiently ‘pacified’ to allow Caesar to burnish his reputation with an abbreviated ‘conquest’ of the land at the end of the earth. Eight hundred ships made the trip from Portus Itius (near or at Boulogne) to somewhere north of Portus Dubris (Dover). The flotilla included several private vessels chartered by merchants who were eager to prospect the new market.

The expeditionary force to Britannia travelled eighty miles inland and crossed a river called the Tamesis, ‘which can be forded – with some difficulty – in only one place’. Roman dignitas usually demanded a bridge, but with British shock troops suddenly appearing along the roads on their high-speed chariots, the soldiers, according to Caesar, waded across the river with only their heads above water. A poet called Varro Atacinus, who was a native of Gallia Transalpina, had already written an epic poem about the first year of the war.* The amphibious crossing of the Thames was exactly the kind of material that would enable poets to celebrate Caesar’s exploits. (A popular historian was unlikely to wonder why the roads of the Britons ended when they came to a river.) Cicero himself had written to request some colourful details that he could use to describe the conquest of Britannia, and Caesar had obliged with ‘a copious letter’: ‘the approaches to the island are known to be guarded with wondrous walls of massive rock’. Unfortunately, the pickings were poor, Cicero reported to a friend:

It is also now ascertained that there isn’t a speck of silver on the island, nor any prospect of booty apart from captives, and I fancy you won’t expect any of them to be highly qualified in literature or music!

Shortly after the defeat of Cassivellaunus, the warlord who had been chosen to lead the British resistance, Caesar was sitting in a room paved with mosaics and marble somewhere in southern Britain near Verlamion (St Albans). A soldier with a drawn sword stood behind him while he dictated letters to a slave. Caesar was said to be capable of composing several letters at the same time, even on horseback. The previous spring (55 BC), while crossing the Alps to rejoin the army in Gaul, he had written a grammatical treatise on the subject of analogy. The room in which he sat had not been furnished for his personal comfort. His baggage train always included a supply of mosaic squares and marble veneer so that important guests such as Roman merchants and foreign kings could be properly entertained. He wrote to Cicero: Britain had been ‘dealt with’ (which was to say, the four kings of Cantium and the warlord Cassivellaunus had surrendered): ‘Hostages taken, but no booty. Tribute, however, exacted.’

The letter was dated ‘Shores of Nearer Britain, 26 September’. The wooden tablets were tied with string and sealed with wax. They would reach Cicero in Rome on 24 October, two days after a letter from Cicero’s brother Quintus, who had joined Caesar as legatus. The adventure had been largely fruitless though not on the whole unpleasant. Quintus had written five plays in his spare time. The fact seems to have slipped between the floorboards of history: the first literary works known to have been composed in the British Isles were four Greek tragedies and a play called Erigone (lost in the post between Britain and Rome). In the fabled land beyond the edge of the known world, Roman soldiers had staged a theatrical performance – probably of Erigone: the mythical subject would have provided light relief and a chance to laugh at the barbarians. Erigone’s father introduces his compatriots to wine. Mistaking their intoxication for a fatal illness, they stone him to death. It was a joke among the Romans that the Celts had started adding water to their wine because they thought it might be poisoned.

That September, just before the equinox, the army and all the travelling negotiatores set sail after dark with a cargo of British prisoners and reached Gaul at daybreak. From Portus Itius, Caesar returned to Samarobriva. After the summer droughts, there was a shortage of grain, exacerbated by the Roman policy of destroying the enemy’s wheat fields. A population already weakened by war would have to suffer the horrors of famine. The minimum daily requirement of the Roman army in Gaul – without counting fodder – has been estimated at one hundred tons of wheat. In assigning their winter quarters to the legions, Caesar spread them over a wider area than before ‘in order to remedy the lack of corn’. In the autumn, tribes from Armorica (Brittany) and the Rhineland rose up against the Romans, and ‘throughout that winter, there was barely a moment when Caesar was not receiving intelligence of the councils and commotions of the Gauls’. But the disciplined legions prevailed, and ‘not long after those events, Caesar had a more peaceful time of it in Gaul’.

The sun god of the Celts is practically invisible until the end of the Gallic War, which is hardly surprising since the only accounts of the war are the seven books of Caesar’s Commentaries, the eighth book, written by his lieutenant Aulus Hirtius, and various historical fragments and anecdotes, none of which is Celtic. Apart from conventional references to ‘Fortuna’, Caesar says nothing of the actions of gods and never mentions the divinatory powers of his friend, Diviciacus the Druid. Yet the Druid augurs, who ‘settle nearly all disputes, whether public or private’, and who frequently used their influence to stop battles, certainly played a major role in coordinating Gaulish military strategy.

Hirtius mentions a certain ‘Gutuater’ or ‘Gutuatrus’ who was accused of masterminding the great uprising of 52 BC. The word ‘gutuater’ has been found on several inscriptions: it was not, as Hirtius supposed, a man’s name, but a title – ‘master of invocations’. Later, when the Druids had been outlawed, the word was used as a generic term for ‘priest’. The gutuater who instigated the rebellion in 52 BC was a predecessor of Sacrovir (‘holy man’), who led the revolt of AD 21 in the university town of Augustodunum (Autun), and of the Druids of Anglesey, who were ‘the power that fed the rebellion’.

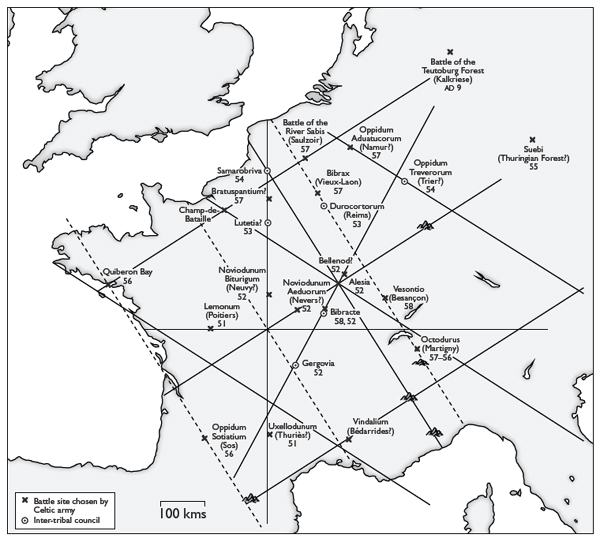

These powerful, priestly figures – Gutuater, Sacrovir and the Anglesey Druids – remained undetected until their final defeat. Many more must have fled after the Gallic War and vanished into Britannia. They are little more than ghosts in the historical record. Yet evidence can be found of their conduct of the war. A consistent strategy bears the marks of Druidic computation. Whenever the site of a battle was chosen by the Celts, it lay somewhere on the solar network. Bituitos of the Arverni, like Hannibal before him, had fought the Romans where the Via Heraklea crosses the Rhone. Sixty years later, the Gauls placed themselves whenever possible in auspicious solar locations. Caesar himself diplomatically followed ‘the custom of the Gauls’ when convening general councils of the pro-Roman tribes, though he certainly had no idea how those places of assembly had been chosen, and just as he had been unable to discover even the most basic facts about Britain, he had only the faintest inkling of Druidic warcraft. The closest he came to a perception of Celtic strategy was in his dealings with the Suebi.

The Suebi, according to their custom, had called a council and given orders . . . that all who could bear arms should assemble in one place. The place thus selected was near the centre [‘medium fere’] of their territories, and they resolved to await there the arrival of the Romans and to do battle on that spot.*

From a modern military point of view, the stubbornness of the Celtic armies seems tragically self-defeating. In eight years, their tactics barely changed. When the Gaulish leader Vercingetorix urged the adoption of Roman practices (scorched earth and fortifications), he was treated as a young upstart by the Gaulish nobles. But he, too, would follow the directions of the Druids. To expect the Celts to have learned practical lessons from the Romans would be to misunderstand the nature of religious thought. In fighting their battles where the gods decreed, they were fulfilling a divine purpose. The earth that the Romans were devastating was not the only world.

50. The Gallic War and Gaulish strategy

The thousands who died on the paths of the sun god would be reincarnated. At a certain moment in his battle with the Nervii, Caesar came very close to seeing this mysterious process with his own eyes:*

But the enemy, even in the last hope of salvation, showed such great courage that, when those in the front rank fell, the men behind stepped onto their prostrate forms and fought on from their corpses.

Almost every one of those battles was won by the Romans. Not all were military triumphs. Some were not even battles, unless fleeing children can be counted as enemy combatants:

The rest of the multitude, consisting of boys and women (for they had left their homes and crossed the Rhine with all their families), began to flee in all directions, and Caesar sent the cavalry in pursuit. Hearing the noise in their rear, the Germans saw their families being slain; they threw away their arms and abandoned their standards.

Caesar’s report to the Senate on the German massacre appalled Cato, who thought that it brought shame on the Roman people. Pliny later described Caesar’s career total of ‘one million one hundred and ninety-two thousand men’ killed as a ‘crime against the human race’ (‘humani generis iniuria’), but he acknowledged that circumstances had forced Caesar’s hand: to the imperial mind, Caesar was avenging ‘insults’ to Rome and consolidating the frontiers of the empire, and if the buffer zone eventually stretched to the ends of the earth, that was all to the good.

Within eight years, a large percentage of the population of Gaul was wiped out. The pre-war population can be roughly estimated at eight million. Caesar’s figures suggest a total military force of two million: the Helvetian census (p. 150) implies that combatants, who included women, made up a quarter of the total population. Eight million people could easily have been supported by Gaulish agriculture in its pre-Roman state. The death count is obviously hard to establish. ‘A great number’ is Caesar’s usual indication of the tally – he uses the phrase ‘magnus numerus’ twelve times, coupled with verbs meaning ‘to kill’ – but there are enough statistical details to give a sense of scale:

Helvetii and allies: reduced from 368,000 to 110,000.

Nervii: reduced from 60,000 men to fewer than 500; of 600 senators, only 3 survived.

Aduatuci: about 4000 killed; 53,000 sold into slavery.

Seduni: over 10,000 killed.

Veneti: most of the tribe killed in battle, the remainder sold into slavery, and the entire senate put to death.

Aquitanian and Cantabrian tribes: ‘barely a quarter’ of 50,000 left alive.

Bituriges (at Avaricum): reduced from 40,000 to 800.

These figures refer to civilian as well as military casualties. The 39,200 killed at Avaricum (Bourges) included ‘women, children and those weakened by age’. People who died later on as a result of famine and disease are, of course, missing from the figures. Taking only the war years into account, an average death toll applied to all the tribes that were slaughtered ‘in great numbers’ suggests total figures in the region of one million dead and one million enslaved, which is the estimate given by Plutarch in his Life of Caesar. The number of Gauls and Germans sold into slavery probably exceeds the number of slaves shipped to the American colonies in the eighteenth century.

The wholesale massacre of Celts was not just a result of the fortunes of war and the circumstances of particular battles. On three occasions, Caesar applies the verb ‘depopulari’ to Roman operations. This is usually translated as ‘ravage’ or ‘plunder’, but at least once, it has its literal sense: ‘depopulate’. The comprehensive extermination of tribes was a deliberate strategy, made possible, in part, by the Gauls’ mobilization of entire populations. (Celtic soldiers went to war with their families in tow.) After the battle with the Nervii in 57 BC, Caesar noted that ‘the race and name of the Nervii were nearly annihilated’. Four years later, it was the turn of the Eburones to have ‘their name and stirps [current generations and all future descendants] obliterated’.

Even ignoring the loss of income and labour, these quasi-military operations were often counter-productive. Tactical genocide had at least two serious drawbacks. First, as Caesar had observed when the Helvetian migrants left their homeland, large parts of the country were left defenceless against potentially less tractable enemies from across the Rhine, though the danger could be mitigated in the short term by the destruction of buildings and crops. Second, what remained of society in the zones of annihilation was catastrophically destabilized. As the war went on, far beyond the months when Caesar had first reported that ‘all of Gaul was pacified’, the Celtic armies took on a different appearance. For the remainder of the war, the legions would be harried by bands of ‘desperadoes’, ‘robbers’ and ‘runaway slaves’. In the lands of the Unelli (the Cotentin Peninsula), ‘a great multitude of wreckers and thieves came together from all parts of Gaul, called away from their farming and daily chores by the hope of plunder and a passion for war’.

It was something of a miracle that the greatest military coalition of Celtic tribes in history emerged from this disaster zone that stretched from the Ocean to the Rhine.

One day at the end of the winter of 53–52 BC, the sun rose at Cenabum (Orléans), and the Roman merchants who had been living in the town since before the war were massacred. The Gaulish message system transmitted the news to the Massif Central and the plateau of Gergovia. There, in the chief oppidum of the Arverni, ‘a young man of the highest ability and authority’ called Vercingetorix (‘Great Warrior King’) put the next stage of the plan into action.

Ambassadors were sent throughout the western half of Gaul, from the Parisii to the Ruteni and along the Atlantic seaboard. Their mission was to assemble a pan-Gallic army. Cowards and appeasers were to be tortured and burned to death; less serious offenders would have both ears cut off or one eye gouged out. There seems to have been little need of such encouragements: almost all the tribes of Independent Gaul declared their support for Vercingetorix – even the Aedui, who until then had remained loyal to Rome. When Caesar learned of the rebellion, he returned from Italy, placed the province in a state of emergency, and marched his soldiers over the snowy Cévennes. This time, when he reached the Loire and the heart of Gaul, he would be confronting a nation determined to recover its freedom.

As far as one can tell from Caesar’s account, Vercingetorix was a ruthless and effective general. His father, Celtillus, had been elected supreme leader of the Gauls. But Celtillus had tried to turn the republic into an absolute monarchy and had been executed by the state. Vercingetorix was suspected of harbouring the same design, but the political institutions of the Gauls were remarkably flexible. (Caesar twice refers to their propensity for taking a vote as ‘fickleness’ and ‘eagerness for political change’.) In Britain, Cassivellaunus, who had tyrannized his neighbours the Trinovantes, had been asked to organize resistance to the Romans. Now, the son of an executed dictator was entrusted with the salvation of Gaul. Even after several defeats and his destruction of twenty Biturigan oppida in a vain attempt to starve the Roman army, Vercingetorix was hailed as ‘the finest of leaders’.

At Gergovia, the young Arvernian general seems to have won a great victory against the Romans. A century later, Plutarch reported that the Arverni ‘still show visitors a small sword hanging in a temple, which they say was taken from Caesar’. According to Caesar himself, Roman discipline broke down at Gergovia: ‘The soldiers thought that they knew more about victory and its means than their commander-in-chief.’ (In the Commentaries, successes are attributed to a singular ‘Caesar’, whereas setbacks are usually described with a generalized plural.) With the province of Gallia Transalpina already trembling at the thought of a barbarian horde less than three days’ march to the north, Caesar would not have wanted to inform the Senate that disaster had stared him in the face at Gergovia, but so many soldiers, merchants and slaves were arriving in Italy with tales of the war in Gaul that he was forced to make concessions to the truth. ‘Having achieved what he intended [at Gergovia], Caesar ordered the retreat to be sounded . . .’ He admitted to the loss of forty-six centurions and ‘somewhat fewer than seven hundred soldiers’.

If the war had ended at Gergovia, Vercingetorix might have become the leader of a unified Gaul. A nation would have existed on the north-western frontiers of the Roman empire in which the benefits of Roman civilization were enjoyed without the humiliation of military defeat. At Alesia, a gigantic bronze statue commissioned by Napoleon III shows Vercingetorix as a moustachioed Viking. This is not the barbarian general who spent the last five years of his life in prison on the Capitoline Hill before being paraded in Caesar’s triumph and then strangled in his cell. This is the military genius who told his army that ‘not even the whole earth could withstand the union of Gaul’. Since almost fifty tribes with proud traditions of belligerence elected him as leader and followed him to the end, he deserves his place in history as the first French national hero. The problem is that having defeated Caesar at Gergovia, this Napoleon of the Iron Age now did something so ‘unusual and extraordinary’ that, as Montaigne and countless other disappointed patriots have pointed out, ‘it appears to defy military custom and logic’.

Gergovia lies on the solar path that joins the burial place of the Delphic treasure to the mother-city of the Celts (Alesia). One hundred Roman miles from Gergovia, on the same solar trajectory, stands the Aeduan capital of Bibracte. This is where Vercingetorix next appeared, at a general council of all the tribes. He was again proclaimed commander-in-chief ‘by popular vote’. From Bibracte, following the same line, he marched to the north-north-east. At the same time, Caesar was skirting the edge of the Lingones’ territory and heading for the lands of the Sequani in the hope of finding a safe route south to the province.

Caesar’s itinerary was the ancient ‘tin route’ along the upper Seine: it would have taken him past the hilltop ruins of a yellow palace where the Lady of Vix had lived over four centuries before. A few hours’ march from Alesia, he met the Gaulish army. Following the line from Gergovia and Bibracte, Vercingetorix would have intercepted Caesar near the Celtic settlement of Bellenod. The river mentioned by Caesar in his account of the battle would be the infant Seine, and the hill that the Gauls defended the place once called ‘les Châtelots’, which indicates a fortified enclosure.

The German cavalry recruited by Caesar charged up the hill and routed the Gauls. Several important prisoners were taken, including the man whom the Druids had elected chief magistrate of the Aedui. It was then that Vercingetorix seemed to relinquish command to a higher authority. He retreated to Alesia and immured himself and all his army inside the oppidum. On that elliptical hill at the heart of Heraklean Gaul, an army of eighty thousand settled in and waited for the attack. ‘Why’, asked Montaigne, ‘did the leader of all the Gauls decide to shut himself up in Alesia? A man who commands a whole nation must never back himself into a corner unless he has no other fortress to defend.’

The Gaulish army, according to Caesar, occupied ‘the part of the hill that looks towards the rising sun’. A sanctuary has been found there, near a healing spring, dedicated to a Celtic equivalent of Apollo. The Romans immediately began to surround the hill with turreted ramparts, fields of pits and sharpened stakes, trenches twenty feet deep and a moat filled with water diverted from the river Ozerain. Caesar was as busy as a spider when it feels the first twitch of the fly. His lovingly detailed description of the siege works translates his glee at Vercingetorix’s blunder. Before the oppidum was completely encircled, Vercingetorix ordered a levy of all the tribes: ‘12,000 each from the Sequani, Senones, Bituriges, Santones, Ruteni and Carnutes; 8000 each from the Pictones, Turoni, Parisii and Helvetii’, etc. The total number of soldiers requisitioned was 282,000.*

About three weeks later, the pan-Gallic relief force assembled in the lands of the Aedui. Since Celtic armies marched and fought in tribal regiments, the horde would have been an ethnographic map of Gaul. Some were dressed in chainmail (a Celtic invention), others in leather cuirasses. All of them carried brightly painted shields and cloaks fastened at the shoulder with a brooch. Their cloaks and trousers were striped, with checks of many different colours. Some of the warriors wore iron helmets crested with wings or a solar wheel. Those from the poorer regions wore sheepskin skull-caps and stuffed woollen bonnets. Their hair was blanched and stiffened with lime-water so that it looked like the mane of a horse. Others were clean-shaven and had feathered, wreath-like hairstyles. They might almost have passed as Romans.

A census was taken (this was the source that Caesar would use when he wrote up his account): 258,000 soldiers had answered the call. Accordingly, the Roman fortifications formed two lines of defence – one facing the oppidum, the other facing the plain from where the relief army would arrive.

By entombing his warriors in the sacred town of Herakles and Celtine, and by summoning a quarter of a million soldiers to the same place, Vercingetorix or the Druid augurs had presented Caesar with a general’s dream – the chance to inflict total defeat on the combined forces of the enemy. The siege began in late August or early September and lasted long enough for the jaws of famine to tighten on the eighty thousand. The population density of the beleaguered oppidum would have been four times that of modern Paris. After about thirty days, the civilian population was evacuated, but their exit was blocked by the Romans and they died of starvation under the eyes of the besieged. When the relief army arrived, it was massacred by the legions within sight of the ramparts.

Inside the mother-city, another council was convened: it was decided that Vercingetorix should surrender. He donned his finest armour and trotted out of Alesia – according to Plutarch – on a beautifully caparisoned horse. He rode in a circle around Caesar, dismounted, dropped his armour on the ground, and sat at the conqueror’s feet. The survivors were divided up among the Roman soldiers. In place of booty, each man received a slave, and since, by that stage of the war, the legions were labouring under the weight of plundered treasure, even a half-starved porter was a boon.

The Alesia that can be seen today on the hill above the village of Alise-Sainte-Reine is the Roman town that replaced the oppidum. The oldest part is the temple to Ucuetis, a god of metalworkers. Its stone footings, next to the table d’orientation, trace the ground-plan of an earlier temple. The museum of Alesia is unaware of the fact, but unlike the other buildings, the Celtic temple is oriented by its major axis on the solstice line from Châteaumeillant. There are few other signs of Druidic calculations – the army that faced the rising sun, two sorties launched by the Gauls when the sun was highest in the sky, and Vercingetorix’s final circumambulation of Caesar. These are the only hints that Alesia had once been the focal point of a solar sanctuary as large as Gaul itself.

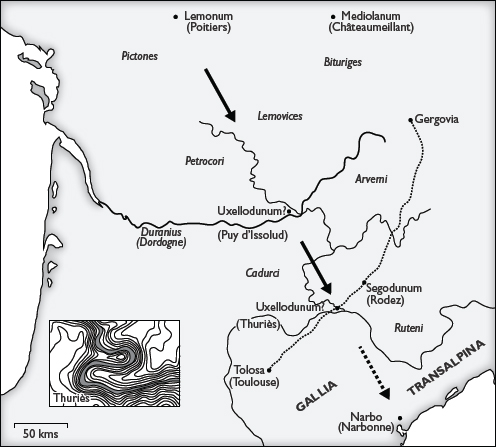

At Alesia, the Gaulish cause was lost. But there was to be one other ‘last stand’. Throughout that winter and the following spring (51 BC), the legions were busy stamping out the fires of rebellion that still burned in other parts of Gaul. In early summer, a Gaulish army was defeated at the siege of Lemonum (Poitiers), which lies on the same latitude as Châteaumeillant. Vercingetorix’s most trusted general – a leader of the Cadurci tribe named Lucterius – escaped from Lemonum and joined forces with a leader of the Senones called Drappes. They assembled a ragged army of two thousand warriors. Lucterius was already known to Caesar as ‘a man of the utmost audacity’, but the Cadurcan’s plan was more than audacious, it was suicidal. Abandoning the ruins of central Gaul to the Romans, Lucterius and Drappes would march south to attack the Roman province.

The direct route from Lemonum to Narbo, the capital of the province, led through the lands of the Cadurci, where Lucterius had his power-base. He and his army passed the Duranius (the Dordogne) and struck out across the region of limestone plateaux where the rivers run through deep gorges. Here, where the warmth of the south begins to prevail over the moist winds of the Atlantic, Lucterius was in his home territory. Word reached him that two Roman legions had set off in pursuit. He realized, says Hirtius, that ‘to enter the province with an army in the rear would mean certain destruction’. But the region later called the Quercy (from ‘Cadurci’) was the natural habitat of fugitives. Long before the Celts, a primitive race had lurked in the tortuous caverns that led to the lower world. In the valleys of the Lot, the Aveyron and the Viaur, the crags that jut out of the woodland at river-bends look like citadels, and the citadels look like crags.

Lucterius chose what appeared to be an impregnable oppidum. Its name was Uxellodunum, from uxellos (‘high’) and dunum (‘hill fort’). Before the war, Uxellodunum had been a protectorate of his tribe. It was a natural fortress: a river almost surrounded it, ‘very steep and rugged cliffs defended it on all sides’, and on the narrow strip of land that connected the oppidum to the outside world, ‘the waters of a copious well burst forth’. Its only obvious weakness was a large area of high ground facing the oppidum from which anyone trying to enter or leave could be seen.

Despite the meticulous topographic description by Hirtius, no one knows where the last major battle of the Gallic War was fought. ‘Uxellodunum’ was a common Celtic place name, and several oppida in the same region may have shared it,* but since the final resting-place of Independent Gaul is a matter of national historical importance, the French Ministry of Culture, in 2001, following the lead of Napoleon III, declared the plateau of the Puy d’Issolud in the Lot département to be ‘the official site’ of Uxellodunum. Six hundred and thirty-four arrow-heads, sixty-nine catapult darts and other Roman weaponry prove that a battle took place there in the mid-first century BC. Unfortunately, not a single detail of Hirtius’s description corresponds to anything at Puy d’Issolud, and a war of words still rages between the three towns that claim to have been Uxellodunum.

Three kilometres to the east of the Gaulish meridian, on the borders of the Cadurci and the Ruteni, there is a place that no one has ever suspected of being Uxellodunum. It matches Hirtius’s description exactly. The village is now called Pampelonne. The steep-sided promontory on its eastern edge, in a tight bend of the river Viaur, bears the old name of the town, Thuriès. A hamlet, first recorded in 1275, once clung to the cliffs; its last remnants disappeared when the hydroelectric dam was built in the 1920s, but the impressive ruins of a medieval castle still bear witness to its strategic importance.

Thuriès castle stood on the Iron Age route that connected Aquitania to the lands of the Arverni. It was the stoutest fortress in the region; its lords grew rich on tolls exacted at the river crossing – which is why, one day in the 1360s, a small band of Gascon mercenaries led by the Bastard of Mauléon, wearing handkerchiefs on their heads and talking in high-pitched voices, gathered at ‘the magnificent spring’ on the edge of Thuriès. After filling their pitchers at the fountain, the six ‘women’ strolled into town, then summoned their companions with a horn-blast from the ramparts – ‘and that’, as the Bastard explained to the chronicler Jean Froissart, ‘is how I captured the town and castle of Thurie [sic], which have brought me more profit and revenue every year . . . than I could ever make from selling the castle and all its dependencies.’

Some places are predestined to be battle-sites. Many centuries before Thuriès fell to the Bastard of Mauléon and his band of bogus women, the last Gaulish army, following the direct route from Lemonum to Narbo, would have come to what is now the Puy d’Issolud, the ‘official’ Uxellodunum. Near the bridge over the Dordogne, a battle was fought with arrows and catapults. Continuing along the same direct line to Narbo, the survivors would then have reached the Thuriès oppidum above the river Viaur. Knowing, as Hirtius says, that it would have been madness ‘to enter the province with an army in the rear’, the fugitives decided to make a stand.

Thuriès, which Hirtius may have conflated with the other uxellodunum or ‘high hill fort’ on the route, does in fact lie on or close to the borders of Gallia Transalpina. It also lies on the borders of the Cadurci and the Ruteni, which is what Hirtius’s description implies. Thuriès was a frontier town with a major river crossing on the long-distance route to Aquitania. This might explain why Caesar decided to leave central Gaul to help out at the siege of Uxellodunum: ‘He reflected that, though he had conquered part of Aquitania through [his lieutenant] Publius Crassus, he had never been there in person.’ The oppidum lay conveniently on the route to Aquitania, which is where Caesar, after supervising the siege, would decide ‘to spend the latter part of the summer’.

51. The route to Uxellodunum

The dotted line represents the ancient route from the Auvergne to Aquitania.

The key to Uxellodunum was the ‘copious well’ below the oppidum walls. The Romans eventually succeeded in drawing off its water by ‘cutting the veins of the spring’ with mineshafts. The inhabitants of Uxellodunum surrendered, but not because they were dying of thirst. A prisoner explained the logic of their decision to Caesar: ‘They attributed the drying-up of the well, not to the devices of men, but to the will of the gods.’ To the Romans, this was a mark of primitive superstition, but the Celts were at least as advanced as the Romans in mining techniques, and the digging of mineshafts can hardly have passed unnoticed. From the Celtic point of view, the Romans were acting as agents of a higher authority. The course of the siege – and of the entire war – had been governed all along by the upper world.

At Uxellodunum, within an arrow’s range of the Gaulish meridian, Independent Gaul came to an end. Before he left for Aquitania, Caesar wanted to ensure that this would be the last sputtering of rebellion. The solution was made possible by what he saw as his reputation for ‘lenitas’ (‘mildness’ or ‘softness’). No one would accuse him of acting out of ‘natural cruelty’ if he inflicted an ‘exemplary punishment’ on the people who had borne arms against the Romans. He would allow them to stay alive so that they could serve as advertisements of Roman justice: ‘Itaque omnibus qui arma tulerant manus praecidit’. ‘Praecidit’ means ‘cut off’; the noun, ‘manus’, is sometimes translated as ‘the right hand’, perhaps because the fourth-declension accusative plural looks like a singular. The correct translation is ‘the hands’. The legions once again gave proof of their tireless efficiency, perhaps, too, of their frustration at ‘the oppidum-dwellers’ stubborn resistance’. The deliberate spoiling of human merchandise would show that Caesar was in earnest . . . The operation was performed, and, that autumn, the men and women of Uxellodunum saw the sun of southern Gaul ripen what remained of their crops but were unable to reap the harvest, having no hands with which to hold their tools.

A winter in Gaul, described by Diodorus Siculus in the first century BC:

And the land, lying as it does for the most part under the Bears, has a frigid climate and is exceedingly cold. For during the winter, on cloudy days, snow falls on the earth instead of rain, and in clear weather, ice and heavy frost are so abundant that the rivers freeze over and are bridged by their own waters. For not only can small bands of travellers who happen to pass that way continue their journey on the ice, but even huge armies with all their beasts of burden and heavily-laden vehicles are able to reach the other side quite safely. . . . And since the natural smoothness of the ice makes the crossing slippery, the Celts scatter chaff on it to make the going more secure.

In the historical record, the years following the conquest of Gaul are covered with a blanket of snow. We know only that, between 46 and 27 BC, local rebellions broke out among the Bellovaci, the Treveri and the Morini, but a generation of warriors had died, and the legions who camped in the oppida watched over hungry populations of grandparents and children. The archaeological record shows that, with a few exceptions, the old oppida were gradually abandoned for more practical settlements on lower ground. These became the Roman towns whose imperious remains still dominate the muddy scrapings of Iron Age excavations.

The siting of the new towns was determined, not by the paths of the sun, but by the motions of men. By the mid-first century AD, many of the oppida had fallen into disrepair. Some shrines were still tended; columns of smoke could be seen rising from charcoal-burners’ fires and metalworkers’ forges; but beyond the building-sites and streets of Augustonemeton (Clermont-Ferrand) and Augustodunum (Autun), Gergovia and Bibracte stood on the horizon like memorials to a lost world.

The short journeys of the oppidum-dwellers from hilltop to plain were the last migrations in the heroic age of the Continental Celts. The tide had been going out since the expedition to Delphi, and it would continue to ebb until Celtic societies lingered only on the shores of the Ocean in countries that the legions would have been happy to leave to the savages. From the siege and destruction of the Celtiberian oppidum of Numantia in 133 BC to the massacre of the Caledonian tribes at the battle of Mons Graupius in AD 83 (p. 265), the history of the Celts in their westward retreat seems to call for the plangent, piped tones of national self-pity that never fail to accompany their filmed adventures.

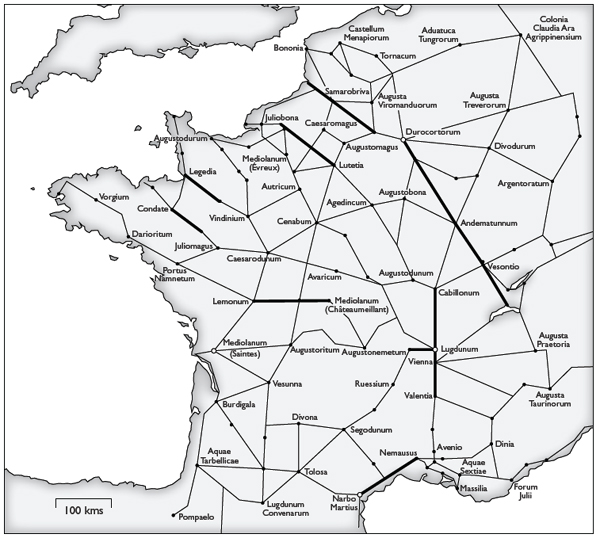

The Druidic network seemed to fade like a shadow when a cloud covers the sun. Their teachings had never been inscribed on paper or stone, and the system of solar paths left few material traces on the landscape. Some sections of road followed the paths – the tin route from the north of Paris to the oppidum at Fécamp, or the route from the Alps to the British Ocean through the lands of the Lingones and the Remi. Just as parts of the old Heraklean Way had become sections of the Via Domitia, these routes were incorporated into the Roman road network. They still exist – their solstice alignments unrecognized – like the foundations of pagan temples buried under churches. But apart from these sparse strands of tartan weave, the surveys that produced the Roman network show no evidence of solar orientation.

The roads of the Romans were centred on the town of Colonia Copia Felix Munatia, later renamed Lugdunum (Lyon). Like the three Gaulish Mediolana that became important junctions in the network (Châteaumeillant, Évreux and Saintes), ‘Lugh’s hill fort’ might have been chosen as a place of religious significance to the natives: it lay ten minutes to the east of the Gaulish meridian and one quarter of a klima to the south of Châteaumeillant. But its location at the confluence of the Rhone and the Saône was above all a matter of commercial and administrative expediency.

52. Principal Roman roads of Gaul

The thicker lines indicate sections of road on Celtic orientations.

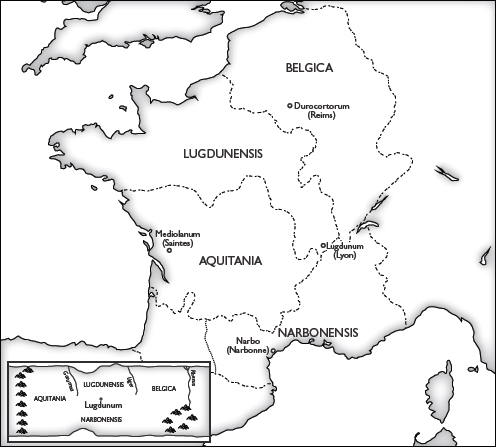

With Lugdunum as its capital, Gaul was divided into provinces in 27 BC. The gods played no part in this reorganization. A single province encompassed the foothills of the Alps and the ports that faced Britannia, while the chilly coasts of Armorica came under the same jurisdiction as the sunny vineyards of Lugdunum. The shape of early Roman Gaul has become so familiar that its bizarre configuration is never questioned or explained. To the Romans, no explanation would have been necessary. The new boundaries accurately reflected Gaul as seen by a Roman geographer. This was the shapeless earth of mortals, charted without the guidance of a sun god.

53. The provinces of Gaul

The provinces of Gaul after the Augustan Settlement of 27 BC, and the Roman logic of their borders. The dotted line represents the earlier western border of Gallia Narbonensis.

In the Roman capital that is now Lyon, the magnificent though slightly outdated Musée de la Civilisation Gallo-Romaine appears to have been taken over by Celtophile exponents of counterfactual history. If Vercingetorix had defeated Caesar at Alesia, and if Lucterius had crossed the borders of the province and reclaimed the Heraklean Way, this is what one might expect to see: the monumental plinths of marble statues carved in the first century AD with the names of important Gauls, publicly declaring their pride in their Celtic heritage:

To Lucius Lentulius Censorinus of the PICTAVI,* amongst whom he has held every post of honour, commissioner of the BITURIGES VIVISCI . . .

To Quintus Julius Severinus of the SEQUANI . . . patron of the most splendid corporation of boatmen of the Rhone and the Saône, twice honoured by the Council of decurions of his city with statues bearing witness to his integrity.

To Caius Servilius Martianus, ARVERNIAN, son of Caius Servilius Domitus, priest of the temple of Roma and Augustus, the three provinces of Gaul.

The names of warlike tribes whose homelands had been ravaged by Caesar are displayed with all the pomp of a victorious nation. Elsewhere in the museum, a bronze tablet discovered in Lyon reproduces Emperor Claudius’s speech to the Senate in AD 48. Claudius proposed that loyal and wealthy citizens of Gallia Comata be allowed to sit in the Senate. ‘Hairy Gaul’ was no longer beyond the pale. Soon, the tribes of Gaul would rename their principal towns, replacing the Roman name with that of the tribe, which is why metropolitan France is one of the most visibly Celtic countries in Europe. The Remi live in Reims, the Bellovaci in Beauvais, and the Turones in Tours; Auvergne is the province of the Arverni; the Bituriges, who were nearly exterminated by Caesar, still inhabit Bourges, and the Parisii still have a capital on the Seine.

Gaul recovered from the war, psychologically and materially, within two or three generations. Unlike other vanquished civilizations, the Gaulish Celts did not punish or deny their gods. They continued to worship them under the Romans. A year or so after Claudius’s speech, the Arverni commissioned a colossal statue of Mercury (the avatar of Lugh) from a famous sculptor for their temple on the Puy de Dôme. It cost forty million sesterces and was the largest statue in the world until the same sculptor was ordered to produce an even larger statue of Nero.

Though it was built of stone instead of wood, the temple of Mercury on the summit of the Puy de Dôme has the traditional, deceptive shape of Celtic shrines. Its corners look like right angles, but one axis is oriented on the local summer solstice, the other on the solar path from Châteaumeillant. Like so much else in Celtic Gaul, these details have slipped into oblivion, but they show that Lugh was still a living presence in the Roman empire. His power was acknowledged by the Romans when it was decided that the birthday of Emperor Claudius, who was born in Lugdunum, should fall on the feast day of Lugh (1 August).

At Alesia and Uxellodunum, the gods’ will had been done. According to Caesar, the Druids sacrificed large numbers of people ‘for state purposes’. They preferred to use convicted criminals, but ‘when there [was] a shortage of such people’, they sacrificed the innocent. The eight-year-long war in which so many warriors and civilians had passed into the other world had been a heavy harvest. Usually, the sacrificial victims were packed into gigantic dolls in the image of gods with wicker limbs, which were then set on fire. The besieged oppida, crammed with thousands of people, had performed the same religious function. This holocaust can hardly have been the original objective of the Gauls, but it was not the final disaster that it would have been for other nations. The gods had been propitiated, and the Druids were vindicated by the subsequent prosperity of Gaul.

Defeat and subjugation are supposed to be defining characteristics of the Celts. Archaeology has muddled that simple, romantic tale. The exodus from the oppida was not necessarily a trail of tears. The process had begun before the war and it continued long after the conquest. Little is known about the early stages of Roman urbanization in Gaul. In the oppida that became Roman towns, the thatched huts of the natives were swept away and replaced with stone buildings. Architects and engineers imposed a simple street-plan based on two axes – the cardo maximus, which ran approximately north–south, and a bisecting decumanus maximus. These axes frequently followed the alignment of the main roads that led to the town, but the overriding criterion was convenience. Solar orientation in Roman towns and forts is extremely rare. The road that enters Amiens from the south-east on a Celtic solstice bearing was ignored by the Roman town-planners, who matched their street-grid to the course of the river Somme.

There is, however, some compelling evidence that the Druidic system was not immediately abandoned. It may even have been adapted to the new world. The streets of Reims are aligned on the solstice line that joins the Great St Bernard Pass to the British Ocean. The same phenomenon can be seen in the Roman towns of Autun, Metz and Limoges. These alignments, which have kept their secret until now, may reflect the special favour that was shown to certain tribes: the Remi had always been allies of the Romans; the Mediomatrici of Metz and the Lemovices of Limoges sent soldiers to Alesia but were involved in no other battles; the Aedui had rebelled only at the very end of the war, and soon regained their status as ‘Friends of the Roman People’.

Unbeknownst to their modern inhabitants, the streets of these Gallo-Roman towns are the aisles of a temple dedicated to an ancient sun god. Perhaps this materialization of solar paths was to have been the next stage in the development of the system. If Gaul had remained independent, the upper world might have been more comprehensively mapped onto Middle Earth, but many of the priestly planners who would have masterminded the operation had left the country after the Gallic War.

‘Non interire, sed transire . . .’: ‘Souls do not perish but pass after death from one body into another, and this they see as an inducement to valour, for the dread of death is thereby negated’ (p. 116). At the end of the war, many living souls had passed over from Gaul to Britannia, where, as Caesar was told, Druidism had been ‘discovered’. In earlier days, Belgic tribes had migrated to the island that Pytheas had known as Prettanike. Perhaps older traditions of Druidism had been preserved there: ‘Those who wish to make a more assiduous study of the matter generally go to Britain in order to learn’, said Caesar. Some of the Druids who crossed the Channel in the autumn of 51 BC would have been revisiting places and people they had known as students.

Merchants and fishermen putting out from Portus Itius or one of the smaller Channel ports might have carried fare-paying passengers fleeing from the Romans. Even after the battle of Uxellodunum, there had been cavalry skirmishes in the north of Gaul. A leader of the Atrebates called Commios, whom Caesar had used as an ambassador to Britain in 55 BC, having turned against the Romans, had been ‘infesting the roads and intercepting convoys’. But even if the Channel ports were placed under surveillance, no one would have paid much attention, for instance, to an elderly Druid boarding a slave ship or a fishing vessel. It was only much later that the Romans learned to fear the political power of the Druids and outlawed their order.

The Romans would hear of Commios again. Twenty years on, he was installed as king of the British Atrebates: coins bearing his name were issued from a town called Calleva (Silchester). Precisely when and where he escaped from the Romans, no one knows. In the late 70s AD, the Roman governor of Britain, Frontinus, heard a cheerful tale of a Gaulish refugee outwitting his Roman pursuers:

Defeated by the deified Caesar, Commius the Atrebatan was fleeing from Gaul to Britannia. He happened to reach the Ocean when the wind was fair but the tide was out. Though his ships were stranded on the shore, he nonetheless ordered the sails to be unfurled. Caesar, who was pursuing, saw the billowing of the sails in a full breeze. Imagining Commius to be making good his escape, he abandoned the pursuit.

The port of Leuconaus (Saint-Valéry-sur-Somme) lies at the end of the solstice-oriented route from Samarobriva (fig. 16). At low tide, the ocean recedes by as much as fourteen kilometres. On the open horizon of the Bay of the Somme, a sail can be seen at a great distance, out as far as the point where the sand-flats merge with the sea. It might have been from there that Commios sailed for Britain. The legend credits him with the glorious deception, but there is something unmistakably Druidic in that beautiful and magical illusion serving a vital purpose.

When the tide came in, a fair wind would have carried the refugees across the Channel in a single night. At dawn, along the coast that was ‘guarded with wondrous walls of massive rock’, as Caesar had told Cicero, there were many safe harbours; some of them were busy international ports. The hinterland of Britannia was beginning to prosper, and it would be left in peace by the Romans for the next ninety-four years.

The home of Druidism was not quite as uncivilized as Cicero had supposed. The British king who was defeated by Caesar spoke Latin, and despite what Roman historians believed, Herakles himself had set foot on the island. One version of the legend of Celtic origins identifies the father of Celtine as a certain Bretannos. The name is otherwise unrecorded and resembles no word other than Prettanike or Britannia. Somewhere in that cold and foggy land, perhaps along its southern coast, there had once lived a princess sufficiently well endowed, in person and in larder, to seduce a sun god from the Mediterranean.

* Only one line survives of Varro’s Bellum Sequanicum: ‘Deinde ubi pellicuit dulcis levis unda saporis . . . ’ (‘Then, when the smooth swell of a sweet taste enticed . . . ’). This may be an allusion to the wine-inspired migrations of the Celts.

* The unnamed place may have been somewhere in the Thuringian Forest (no. 3 in fig. 43) between the Elbe and the Rhine.

* This was the so-called battle of the Sambre. Pierre Turquin showed conclusively in 1955 that the river ‘Sabis’ of Caesar’s text is not the Sambre but the Selle, and that the battle took place on the site of the village of Saulzoir (Nord). This is now corroborated by the Druidic system: Saulzoir lies precisely on the northern solstice line (fig. 50).

* See the map of the Gaulish confederation on p. 34.

* ‘Uxellodunum’ survives in Exoudun, Issudel, Issoudun and a few other place names. Most have probably vanished. The Uxelodunum (sic) on Hadrian’s Wall above Carlisle is now Stanwix (‘Stone Way’).

* The Pictavi or Pictones of Lemonum (Poitiers).