Between the conquest of Gaul (58–51 BC) and the Claudian invasion of Britain (AD 43), the Druidic system was not just extended across the Channel, it also reached a new level of sophistication. Its evolution in Gaul had been brutally arrested; in Britain, the influx of Druids and stronger trade links with the Continent allowed it to flourish. The Whitchurch meridian, two ten-minute increments west of the Châteaumeillant meridian, was a Continental import. The intermediate line through London – a town that Lludd was said to have rebuilt – may have remained significant as a meridian, but the new, British solstice angle produced new lines of longitude at roughly five-minute intervals: through Pendinas (Aberystwyth), Whitchurch, Oxford, and a fourth line to the east whose importance will shortly become apparent.

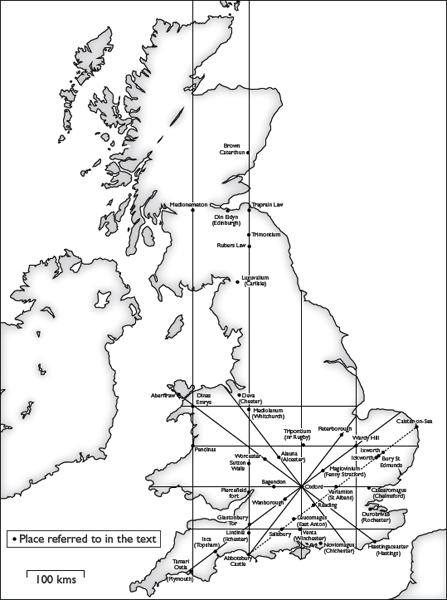

The solstice ratios (11:7 in Gaul, 4:3 in Britain) were equations that could be applied in different circumstances and adapted to political and commercial necessity, but they were also used to fashion lasting features of the inhabited land. The lines that radiated from the Oxford omphalos to Dinas Emrys and other points of the Druidic compass produced a graceful coordination of Iron Age sites. Three or more tribal centres lie on the Oxford parallel, and at least a further five on the Whitchurch meridian. The Pendinas / Aberystwyth parallel, after passing through two county tripoints and the place that became the Roman town of Tripontium near Rugby, reaches its intersection with the easternmost line of longitude at a fortified settlement of the Iceni tribe called Wardy Hill. (See the large map on p. 240.)

At first, some of these places seem devoid of significance, but as the older landscape comes into view, they turn out to have been busy and important. The fenland fortress of the Iceni at Wardy Hill lies at a latitude–longitude intersection and on a solstice line from Oxford. In the other direction, the same line appears to go astray: it misses the capital of the Dumnonii (Exeter) by three kilometres. But this is a line that exists in the Iron Age, not in Roman Britain, and so, logically, it ends at the Exeter suburb of Topsham. This former river port, where the river Exe becomes navigable, is now known to have been the original tribal centre.

The Dumnonian settlement at Topsham was excavated only recently. Many other places on the solstice lines may one day prove to have pre-Roman roots. Some are already seen as probable tribal centres. The Dinas Emrys line continues north-west across the sands of Abermenai Point to the Druid stronghold of Anglesey and Holy Island. It passes through Aberffraw, which became the capital of Gwynedd – one of the Welsh kingdoms that were formed from the old tribal territories after the departure of the Romans. In the other direction, it passes within five hundred metres of a suspected Iron Age settlement near Worcester Cathedral – perhaps the home of an obscure tribe called the Weogora – and, after the tripoint of Kent, Surrey and Sussex, it arrives on the south coast at Fairlight Cove, near the scene of a more recent invasion – Hastings (p. 262).

The size of the canvas on which the sun-paths sketch a lost landscape is hard to estimate. The towns of the Iceni and the Dumnonii are separated by more than three hundred kilometres. On the Whitchurch meridian, the Durotrigan town of Lindinis (Ilchester) lies almost five hundred kilometres south of the Votadini’s capital at Traprain Law (also known by its older name, Dunpelder). Due west of Traprain Law and the oppidum site of Edinburgh, the Pendinas–Dinas Emrys meridian arrives with the precision of a god-transported dragon at the place on the Antonine Wall called Medionemeton. If the Druid surveyors operated at this level of accuracy, there is no reason why the entire island should not have been charted by Belinus and Lludd.

At this distance in time, it seems incredible that two partial maps of the British Druidic system should still exist. The first can be seen in the British Library, which happens to stand on the London meridian. The second is embedded in another map which is familiar, in one form or another, to most British schoolchildren because it depicts the Roman road system.

61. The Four Royal Roads, drawn by Matthew Paris

Some time between 1217 and 1259, a Benedictine monk called Matthew Paris was working in the scriptorium of the abbey of St Albans. St Albans had once been Verlamion, the capital of the pagan Catuvellauni; the Romans called it Verulamium and turned it into one of the most important towns of southern Britain. The first British Christian martyr had died there. Now, in the thirteenth century, it was a centre of learning, a rival of Oxford, which – though knowledge of the fact had long since been lost – lay on the same Druidic line of latitude.

The monk drew what appears to be a crude map consisting of a black oval and four red lines. He described it as a ‘schema Britanniae’ – an outline of Britain. Compared to his other, more flowery maps of the British Isles and the Holy Land, Matthew Paris’s Schema Britanniae is a dull, geometrical doodle. This obviously inaccurate document was once considered to be ‘of extremely slight interest to most scholars of this period’.

The monk had no atlas, no encyclopedia, and no gazetteer other than the old Roman itineraries. He had read Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae: his own copy, containing his marginal notes, has survived. He also knew Henry of Huntingdon’s Historia Anglorum (‘History of the English’, c. 1129). There were probably other, older manuscripts, brown and blotched with damp, their half-legible words like the whispers of a dying saint. There may even have been a map, copied from an ancient design or a mappa mundi like the one that had been displayed at the school of Autun in Gaul (p. 111). The monastery library of St Albans contained treasures that could be found nowhere else.

The subject of the drawing was the marvellous pattern of highways known as the Four Royal Roads. These roads were not some fantastic fable: they existed and were still in use. Three of them were Roman, though the legend claimed that they had been built before the Romans; they were called by the names they had acquired in Saxon times: the Fosse Way, Watling Street and Ermine Street. The fourth road, the Icknield Way, was prehistoric. Historians warn that these Four Royal Roads were primarily a rhetorical trope or figure of speech, not to be taken too seriously.

Eager to discover the literal reality of these fabulous ways, Matthew Paris had read that the southern and northern ends of Britain were ‘Totnes in Cornwall and Caithness in Scotland’, and so he drew a wobbly oval to encompass both places, joining them with an S-shaped line, unaware that Caithness does indeed lie due north of Totnes. Then he drew a neat red line joining Salisbury in the west (at the top of the map) to Bury St Edmunds in the east, and a bisecting line along the major axis of the oval. To these he added two diagonal lines to represent the roads mentioned by Geoffrey of Monmouth as part of the network ordered by Belinus: ‘Two others he also made obliquely through the island for passage to the rest of the towns.’

Like any scholar who wanted to preserve and elucidate an ancient text, the monk now contributed his own interpretation. He knew that half a day’s journey to the north of St Albans, the Icknield Way crossed Watling Street at the priory of Dunstable. This, he assumed, must be the crux of all four roads, and so he wrote the name ‘Dunestaple’ in the centre and drew a box around it. The devil who peered over the shoulder of medieval monks as they copied out their sacred texts must have grinned horribly when he saw the mistake. If the monk of St Albans had possessed the knowledge of a Druid, the truth would have struck him like a revelation. But no shaft of light fell across the scriptorium floor to trace the pagan path of the solstice sun and to show that the line he had drawn between Salisbury and Bury St Edmunds passed, not through Dunstable, but through the very centre of St Albans where he sat, unwittingly drawing a map of Druidic Britain (fig. 62).

This line, like some magically created pilgrim route to the pre-Roman past, is exactly oriented on the British solstice. It has no correspondence in the Roman road system. No Roman road or prehistoric pathway links the places on the line, and yet they all appear along it as precisely as though the original cartographer in the days of legend had acquired a map of Britain on the Mercator projection. Unbeknownst to Matthew Paris, the solstice line which he labelled ‘Ykenild Strete’ connects the ancient abbeys of Saffron Walden, Ixworth, Bury St Edmunds, St Albans, Reading and Salisbury,* as well as several other places whose Iron Age significance is suggested by a name or by archaeological finds: Ashdon, Welwyn, Abbots Langley, Abbotts Ann, Winterbourne Abbas and Abbotsbury Castle. It passes through a suburb of Andover called East Anton, which was once a major road junction: its Celtic name was Leucomagus, the ‘shining’ or ‘bright’ ‘market’. Beyond Salisbury, as if to appose a Druidic seal to the itinerary, the line reaches the Dorset coast near the southern end of the Whitchurch meridian.

If anyone ever doubted that Christian sites replaced earlier pagan sanctuaries, here is the astronomical proof. The name ‘Ykenild’ or ‘Icknield’ was applied in the Middle Ages to various segments of prehistoric pathway and drove road running roughly west to east. The origin of the word is unknown. Two places that preserve the name – Ickworth and Ixworth – are exactly bisected by the St Albans line. Two others that were associated with an ‘Icenhilde weg’ in the tenth century (Wanborough and Hardwell in Uffington) are on the Oxford line from Wardy Hill to Topsham which precisely parallels the St Albans line. They lie just below White Horse Hill and the chalk escarpment on which the prehistoric Ridgeway crosses the Chilterns. Perhaps the mysterious word at the root of ‘Icknield’ was once the collective name of these solar paths.

62. The British network

The network so far. All bearings are exact (tan ratio 4:3).

Matthew Paris’s Schema Britanniae can now be seen for what it is – a remnant of the oldest map in British history. For all its errors and approximations, it preserves the accurate coordinates of an oral tradition that predates the Roman conquest. Beyond this solstice line, in all directions, stretches the great network of Belinus and Lludd, which no single map, legend or book could encompass.

The three other Royal Roads of British legend – the Fosse Way, Watling Street and Ermine Street – were, understandably, conflated by the medieval scholars with the roads of the Roman conquerors. They were among the earliest to be built after the invasion of AD 43, and they seem at first to have no connection with pre-Roman Britain. Considering the apparently undeveloped state of the British hinterland, these great arteries are so impressively precocious, probably completed for the most part within a generation of the Roman invasion, that archaeologists sometimes wonder whether the Romans based their roads on a native network. But since the Britanni are assumed to have been content with meandering tracks and muddy causeways, this is considered unlikely.

The truly peculiar feature of the first long-distance Roman roads in Britain is their extreme accuracy. The angular alignments are so precise that when the road-builders set out from their starting point, they must have known to within a few paces where they were heading, even when the terminus lay far to the north or west. No Roman text describes the building of these roads, and their Latin names are unknown, but the roads themselves are long sentences whose structure and grammar remain quite comprehensible.

Modern surveyors who have studied the Roman network insist that before these roads could be made, an extensive survey must have been carried out. The explanation only makes the achievement more remarkable. Roads of conquest, as today in Afghanistan, are often constructed in advance of a front line, but without air support and satellite positioning, it would have been practically impossible to survey a target area that had yet to be conquered – unless, that is, the foundations of a road system had already been laid . . .

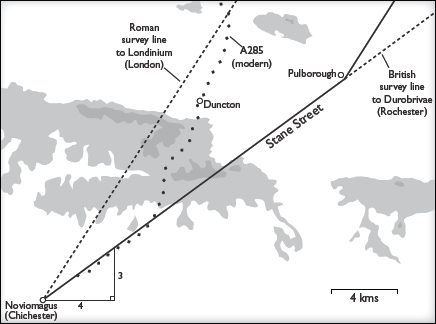

The London to Chichester road, or Stane Street, as it came to be known, seems to be a typical example of Roman expertise. It can be followed from London Bridge along Clapham Road and Tooting High Street, and, if the historical pedestrian manages to keep to the same straight line for sixty Roman miles, the inevitable end-point will be the Eastgate in Chichester. Stane Street is not one of the legendary Four Royal Roads, but it shares with them a curious, Celtic property. The ruler-straight road sets off from the Eastgate in Chichester in what appears to be the wrong direction: instead of heading north-north-east to London, it runs east-north-east to the village of Pulborough. Only there, after twenty-two kilometres, does it correct itself and turn towards the metropolis (fig. 63). Perhaps the surveyors’ intention was to avoid a hillier route across the Sussex Downs – not that Roman road-builders shied away from ferociously steep gradients – but the trajectory of Stane Street is hardly an improvement on the direct line. An easier and faster route would have been the course of the present A285 through Duncton, which keeps to lower ground and follows the projected London line more closely.

The inescapable conclusion is that the road from Noviomagus (Chichester) was originally aimed, not at Londinium, but at the Celtic port of Durobrivae (Rochester) on the river Medway. Noviomagus was the capital of the Regni tribe; Durobrivae was one of the two chief oppida of the Cantiaci tribe. Both tribes had strong trading ties with Gaul, both had reasons to build roads before the advent of the Romans, and since the god Lugh was ‘the guide of their paths and journeys’ (p. 72), the original surveyors angled their road in accordance with his eternal laws. This ‘Roman’ road, which seems to change its mind at Pulborough, runs exactly parallel to Matthew Paris’s Icknield Way, towards the sun that rises over the North Sea at the time of the summer solstice, on a Pythagorean ratio of four and three.

Here, in the network that is supposed to be the great and lasting contribution of Rome to the future prosperity of Britain, the Pythagorean harmonies of the Celts are clearer than ever. During the last century of Britain’s independence, something vast and magnificent was evolving, of which the Chichester road is just one example. Although the Druids’ wisdom was later contaminated by misinterpretations and coloured by the theology of the medieval scholars who recorded its remnants, the truth survived in a recoverable form. None of the medieval scribes could possibly have known this, but the four roads identified in legend as the work of a king or god called Belinus have something quite precise and distinctive in common: these are longest surviving roads in the ‘Roman’ network to be aligned on the British solstice angle.

63. Stane Street

Stane Street: from Chichester to London or to Rochester? The Roman survey line on the left represents the direct route between Chichester and London Bridge. It can be followed on the ground along certain stretches of former Roman road such as Clapham Road and Tooting High Street. The puzzle is this: why does the actual Roman road (the continuous line on the map) deviate so far from the survey line, instead of, for example, following the shorter route of the current A285? A possible answer is that a convenient stretch of British road or path already existed, oriented on the summer solstice and connecting the British towns of Noviomagus and Durobrivae.

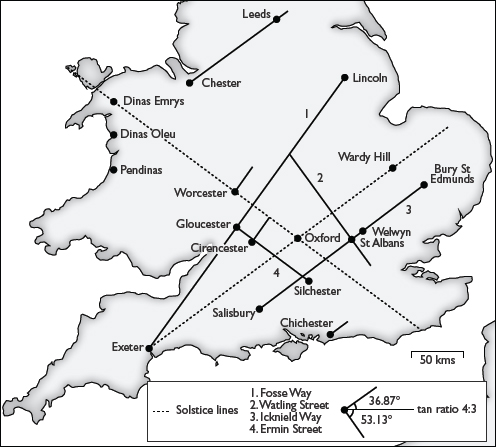

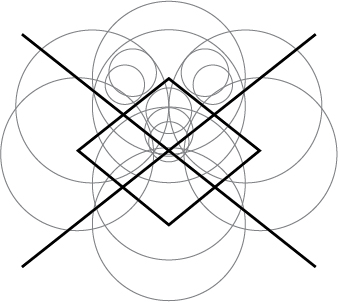

It now appears that these Royal Roads were indeed, as the legend claimed, older than the Romans. They were singled out in the legend from other lines in the network as prime examples of the Celtic system. Each road represents one of the four British solstice bearings (36.87° and 53.13°, and the bisecting lines, 126.87° and 143.13°). The fabled configuration of roads thus produces a complete Druidic blueprint: the Icknield Way is the summer solstice line, bisected by Watling Street; Ermin Street is the winter solstice line, bisected by the Fosse Way.*

64. The Four Royal Roads and the Roman road system

All these survey lines have a tan ratio of 4:3. The Exeter–Lincoln line (the Fosse Way) implies a survey tolerance (acceptable deviation from the survey line) of 0.59°. The southern terminus of the Roman Fosse Way was probably Ilchester, which lies on the Whitchurch meridian: this Roman road has a tan ratio of 3:5 (bearing 30.96°, with a survey tolerance of 0.44°.)

As for the towns that lie along these lines, some, as one might expect, are Roman, but others date back to the pre-Roman Iron Age. In several cases, the ‘Roman’ survey lines are actually a closer match for Iron Age than for Roman Britain. The solstice line from Silchester runs, not to Roman Cirencester and Gloucester, but – via the foot of White Horse Hill – to their nearby Iron Age predecessors, Bagendon and Churchdown Hill. If the same line is extended to the Welsh coast, it arrives at the hill fort of Dinas Oleu (‘the hill fort of Lleu’ or ‘Lugh’) at Barmouth – halfway between Dinas Emrys and Pendinas on the Medionemeton meridian.

The Roman towns themselves may turn out to have existed before the conquest. The evidence is scarcer than it is in Gaul, and at this point in the book there was to have been a speculative passage on the possible solar alignment of late Iron Age towns in Britain. Then, in August 2011, archaeologists from the University of Reading announced that they had uncovered definite evidence of the grid pattern of a native settlement beneath the Roman town of Calleva Atrebatum (Silchester). The Romans could no longer take the credit for the first planned towns in Britain. There was one further detail, about which the official report was understandably discreet, since such things are associated with neo-Druids, ley-line hunters and other muddiers of material evidence: the original British grid of Calleva, unlike the Roman north–south, east–west grid, was aligned on the summer solstice.

The Romans were always surprised by the interregional alliances formed by British tribes. It is just as surprising to see a coordinated British nation emerging before the Romans first landed on the south coast. The British ratio of four and three can be detected on a microcosmic level in certain objects of British Celtic art such as the Aylesford Bucket or the Battersea Shield (figs. 66 and 67); it is also visible on a larger scale, in the temple at Camulodunum (Colchester), whose alignments can now be connected to the history of Iron Age Britain (p. 259). An intriguing passage in Ranulf Higden’s version of the Four Royal Roads legend (c. 1342) suggests that the geometrical formula permeated British Iron Age society on every level and at every scale:

65. The pattern of the Four Royal Roads

Each road is aligned on one of the four British solstice bearings.

Molmutius, King of the Britons [father of Belinus], the twenty-third, but the first to give them laws, ordained that the immunity of fugitives should be enjoyed by the ploughs of the tillers of the soil, by the temples of gods and by the ways that lead to the cities.

The ‘ploughs’ (‘aratra’) were ploughland considered as a unit of land measurement. The exciting implication is that the solar equation was applied, not just to roads and temples, but also to the organization of the countryside. Just as the streets of British Calleva were oriented on the summer solstice, the field systems of Iron Age Britain may have been patterned by the solstice sun. There is a similar echo of a grand Druidic plan in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae. According to his unknown source, the Royal Roads were created when the civitates (states or cities) of Britain were unable to agree on their boundaries. This was certainly a reference to the days when national policy was decided by the Druids, one of whose functions was to settle boundary disputes. The new alignments were devised to settle the matter once and for all, and to ‘leave no loophole for quibbles in the law’. In Britain, as in Gaul, the sun supplied the formula with which no tribe or individual could disagree.

From this formula, fragments of a tribal map of ancient Britain might be pieced together, and the countryside that still exists will begin to shimmer with an unanticipated harvest. Many of the solar paths bisect the points where three or more shires and parishes meet. Some of those places still bear names that consecrate their ancient significance – Three Shire Oak, Four Shire Stone, No Man’s Heath, etc. (p. 297). Unlike diocesan boundaries, which tend to follow natural features, the historic county boundaries often pass through almost featureless landscapes, as though some earlier world has vanished along with the visible logic of its configuration. These territorial divisions are thought to date from the Saxon kingdoms which emerged from the ruins of Roman Britain. The theory that the Saxon kingdoms in turn were based on Iron Age tribal territories now looks entirely plausible.

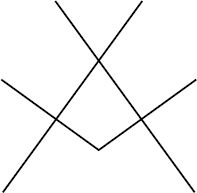

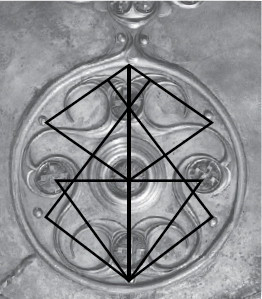

66. British solstice bearings applied to a roundel of the Battersea Shield

67. British solstice bearings applied to the face on the Aylesford Bucket

These protohistoric alignments would be overwritten and obscured by all the later Roman roads that covered the province of Britannia. The Celtic alignments were like cryptic designs on an old parchment that an artist incorporated into new, less geometrical patterns. The medieval scholars who recorded the legends nevertheless communicated the outline of the earlier Druidic network. With the information that remains, and the formula of the Druidic system, the feats of the first Roman road-builders no longer seem so incredible. Celtic Britain appears as on a cloudless day, when there can never be enough time for all the expeditions the sun will allow.

The virtual atlas of these solar paths is so voluminous that if the whole system were described in detail, the preceding two hundred pages would be a brief introduction by comparison. A few possible journeys are described in the epilogue, but since one of the aims of this book has been to show how an apparently abstract, mystical system is corroborated by archaeological evidence and historical events, the more urgent task is to use the map of Celtic Britain to follow the warriors and scholars of the Poetic Isles as they enter the lists of recorded history in AD 43.

* On the transferral of Salisbury Cathedral from Sorviodunum (Old Sarum) to its current site in 1220, see p. 286.

* Ermine Street, which ran approximately north from London, shows no obviously significant bearing, whereas Ermin Street (north-west from Silchester) follows the British solstice bearing. Medieval scholars chose what they believed to be the more important ‘Ermyngestrete’, though in some versions of the legend (e.g. Robert of Gloucester’s thirteenth-century Chronicle), ‘Eningestret’ is paired with ‘Ikenildestrete’, as it is on the map above: ‘Lyne me clepeth eke thulke wey, he goth thorgh Glouceter, / And thorgh Circetre [Cirencester] euene also’.