Of all the books that were never written or that disappeared in the ruins of a library, one of the greatest losses to history must be the autobiography of Caratacus. When the Roman invasion force landed on the coast of Cantium (Kent) in AD 43, Caratacus, son of Cunobelinus, was the ruler of a large part of southern Britain. He became the leader of the British resistance, and held out against the Romans for eight years. By the time he was captured in AD 51, his fame had spread as far as Italy. He was taken to Rome, along with his brothers, wife and daughter, to be displayed in a triumphal ceremony. Normally, the ceremony would have ended with his execution, but when Caratacus was brought before Emperor Claudius, he delivered such an impressive speech in Latin, and then another speech to Claudius’s wife Agrippina, that he was spared the punishment that had been meted out to Vercingetorix a century before. ‘I had horses, men, arms and wealth,’ he is supposed to have said. ‘Is it any wonder that I was reluctant to part with them? Just because you Romans want to lord it over everyone, does it follow that everyone should willingly become a slave?’

The wife and brothers of Caratacus then delivered speeches of their own, expressing ‘praise and gratitude’. Claudius granted them their freedom, and the Caratacus family settled down to live in Rome. ‘After his release’, according to the Roman historian, Cassius Dio, ‘Caratacus toured the city, and, having seen how big and shiny everything was, he said, “When you have these and other such things, why do you covet our little tents?”’

With the Roman legions still laying waste to his native land, Caratacus had to be careful. ‘Little tents’ was a flattering understatement. Wealthy Britons of the first century AD lived in large and comfortable houses stocked with expensive imports. Their diets were more interesting than those of many British people until the mid-twentieth century. They drank wine from wine glasses and flavoured their food with coriander, dill and poppy seeds. A small charred stone excavated from a pre-Roman well in Calleva (Silchester) in 2012 suggests that when she dined out in Rome, the daughter of Caratacus would not have been amazed to taste an olive. If Britain had nothing to compare with the marbled magnificence of Rome, it was probably because, like their Gaulish counterparts, the kings of Britain felt no need of monumental architecture. The Roman invasion was unlikely to change their minds: the imperious Temple to the Divine Claudius that the Romans built in Camulodunum (Colchester) would be seen by the Britons as a blot on the landscape and ‘a citadel of perpetual tyranny’.

Nothing else is known about the life of Caratacus in Rome. The story that he and his daughter became Christians and brought the new religion back to Britain is entirely spurious. If he had any dealings with devotees of a proscribed religion, they would not have been Christians, whom Claudius had just expelled from Rome, but Druids, whose ‘cruel and horrible rites’ the same emperor had banned. The Druids were popularly imagined to be soothsayers and healers with a propensity for human sacrifice and political agitation, but an earlier decree, which forbade Roman citizens from becoming Druids, shows that a Druid could also be an educated speaker of Latin. Since Claudius had recently persuaded the Senate to admit citizens of ‘Hairy Gaul’ to the senatorial class, it would not have been extraordinary if there were Druids living in Rome. Somewhere in that city of shiny monuments, a meeting might have taken place. With the solar map of Britannia unfolded in his listeners’ minds, this is the tale Caratacus might have told.

The invasion of AD 43 caught Caratacus unprepared. He lost a battle somewhere in the south-east, and then another on the river Medway – probably near Durobrivae (Rochester) at the end of the solstice line from Noviomagus (Chichester). In one of those battles, his brother Togodumnus was killed. When the Romans crossed the Thames and marched on Camulodunum (Colchester), Caratacus shifted his campaign to the west. He retreated through the Cotswolds and across the Severn Estuary. Eventually, in about AD 49, he reached the lands of the Silures of South Wales.

Even at this early stage in the conquest of Britain, the conventional view of disciplined Romans and chaotic Celts is untenable. Caratacus had ruled a small empire in the Thames Valley. Now, a child of the civilized south-east, he became the undisputed leader of the ‘swarthy, curly-haired’ Silures – ‘a particularly ferocious’ people, said Tacitus, whose cunning was matched by the ‘deceptiveness’ of their terrain. For a supposedly anarchic group of clans, the Silures were an effective political entity, able to form alliances over wide areas, ‘luring’ other tribes ‘into defection’, as Tacitus snidely puts it, ‘by bribing them with booty and prisoners’.

Along the ridges and valleys of South Wales, a guerrilla war was fought that has left no visible trace. From there, Caratacus moved the theatre of war again, to the north, into the lands of the Ordovices, a week’s march from Roman-occupied Britain. His forces were now augmented, says Tacitus, by ‘those who dreaded the thought of a Roman peace’. His aim was presumably, in part, to open supply routes to the large tribal federations in the east – the Cornovii and the Brigantes – but there was another reason for his gradual retreat to the north-west. Behind the windy bulwarks of Snowdonia lay the holy island of Mona (Anglesey), where the Druids had their stronghold.

Like Finistère, Fisterra and the Sacred Promontory, Mona was one of the ends of the earth. As an island, it belonged to this world and the next. Its connection with the lower world is well attested: between the second century BC and the period when Mona finally fell to the Romans (AD 78), hundreds of bronze and iron artefacts were cast into a lake in the north-west of the island. (The lake, Llyn Cerrig Bach, is now a marshy lagoon on the edge of a military airfield.) The artefacts included swords, slave chains, blacksmiths’ tools and cauldrons. Some of them came from Hibernia, others from Belgic Gaul. They might have been brought as votive offerings by the students who travelled to Britannia to study Druidism.

Now, perhaps, for the first time in their long war against the Celts, the Romans had an inkling of the sacred geography that determined the movements of the enemy. The strategic value of Mona was obvious: the sea was its moat but also its highway. From the harbours of Mona, a troop ship could sail to northern Britain, to Hibernia or to the lands of the Dumnonii in the south-west. While the Romans consolidated their conquest of the south and east, the island fortress of the Druids became ‘the haven of fugitives’ and ‘the power that fed the rebellion’ (Tacitus).

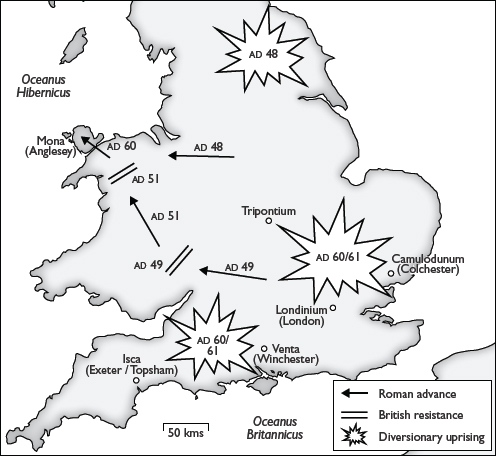

68. The role of Mona in British resistance

Charted chronologically, the movements of the British forces form a pattern of which Mona is the oblique focus. In AD 48, governor Ostorius Scapula marched against the Deceangli of North Wales but was prevented from attacking Mona and its ‘powerful population’ by a sudden uprising among the Brigantes to the east. Soon after that, Caratacus took command of the Silures of South Wales. His strategy, too, seems to have been governed by the need to defend the sacred island: as Caratacus moved north, his lines of resistance always protected Mona. Later, the revolt of the Iceni and their allies would coincide with Suetonius Paulinus’s attack on the island and force him to call off his destruction of the Druids’ shrines (p. 257).

Some historians argue that Druid priests and their island base played a negligible role in the British resistance. This was not the view of the Roman commanders. Agricola considered the invasion of Mona an ‘arduous and dangerous’ undertaking. When Suetonius Paulinus launched his attack, he was hoping to outdo a rival general, Corbulo. In his mind, the conquest of that small island in the Oceanus Hibernicus would be an achievement equal to Corbulo’s recent subjugation of Armenia.

The common soldiers, who included large numbers of Germans and Celts, agreed with their commanders. As they advanced through the hallucinatory landscapes of highland central Wales, they were conscious of approaching a place from which an occult power radiated. They had been reluctant even to cross the Oceanus Britannicus. ‘Indignant at the thought of campaigning beyond the known world’, according to Cassius Dio, they had cheered up only when a flash of light had shot across the sky from east to west – sunwards – in the direction of Britannia. Now, as they chased Caratacus to the north, they saw the clouds gather into a dark thunderhead. It loomed over the mountains of Snowdonia, beyond which the world came to an end. When Roman troops stood at last on the shores of Mona in AD 60, they would be ‘paralysed by fear’ at the sight of ‘women dressed like Furies in funereal attire, their hair dishevelled, rushing about amongst the warriors, waving torches, and a circle of Druids raising their arms to the sky and pouring forth dreadful curses’.

Only the Druids and the British commanders could see the whole panorama. The dragons’ solstice line from Oxford to Dinas Emrys crosses the Menai Strait at Abermenai Point, where the earliest recorded ferry connected Mona with the Dinlle Peninsula, whose name means ‘fort of Lleu’ or ‘Lugh’. It was there, no doubt, at the narrowest crossing, that the Roman legions would push their flat-bottomed boats through the sandbanks and the shallows to find themselves confronting the weird army of Druids. Beyond the strait, the line reaches Holy Island off the north-west coast of Mona and the white mountain of Holyhead which guided sailors on the Hibernian Ocean (fig. 69).

In AD 51, the sun god who had mustered the Gaulish tribes at Alesia a century before induced Caratacus to make what a recent historian has called ‘a crucial error’: like Vercingetorix, ‘Caratacus consolidated his forces for a last stand, giving the Romans exactly what they wanted: a set-piece battle’. The site of this final battle has never been discovered,* but on the map of Middle Earth, the solar signposts point to a place which corresponds in every detail to Tacitus’s description.

The road connecting the two mountain passes that lead to Mona is guarded by the fort of Dinas Emrys, known in older days as Dinas Ffaraon Dandde (‘Hill Fort of the Fiery Pharaoh’). Here, as we saw (p. 230), three solar paths converge: the dragons’ solstice line from the omphalos of Oxford is intersected by lines of latitude and longitude. The hill was once an Iron Age settlement. Now, the only noticeable remains are those of a thirteenth-century tower. Nearby, a ‘lapis fatalis’ (‘Stone of Destiny’) called the Carreg yr Eryr (‘Eagle Stone’) marked the meeting-point of three cantrefi – the medieval districts that are thought to have been based on Celtic tribal kingdoms.

For Caratacus, the fabled hill fort at the intersection of three solar paths was a British equivalent of Alesia. It also happened to satisfy his strategic requirements. The battle was fought, according to Tacitus, ‘in the lands of the Ordovices’ and in a place where ‘advance and retreat would be difficult for the enemy but easy for the defenders’. In front of the fortress ran ‘a river of uncertain ford’ or ‘of varying depth’ (‘amnis vado incerto’): this would be the lake-fed river Glaslyn, which swells rapidly with the rain but which is fordable at other times. Downstream of the lake called Llyn Dinas, the valley is almost blocked by the hill of Dinas Emrys. All around, an ‘impending’ or ‘menacing’ ‘ridge’ or ‘range of mountains’ (‘imminentia iuga’) daunted the Roman commander. This can hardly refer to the modest hills of Shropshire where the battle is often assumed to have taken place.

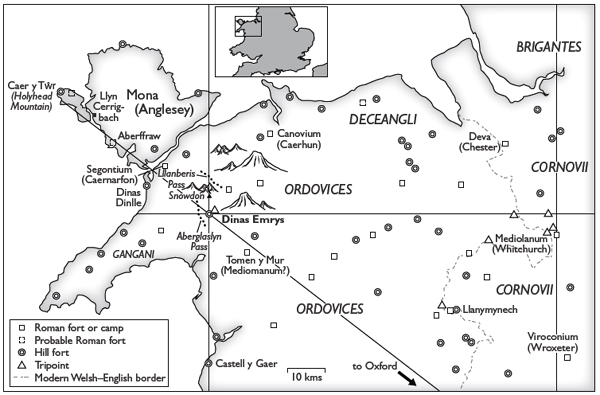

69. North Wales and Dinas Emrys

North Wales and the strategic significance of Dinas Emrys. Most of the Roman forts were probably constructed in the 70s or 80s AD, after the defeat of Caratacus.

The stories that cling to Dinas Emrys like the river-mists are as confused as the archaeological remains. After Caratacus’ death, a memory of his great battle with the Romans may have survived in bardic records or local legends, which then became entangled with the original myth. Centuries later, when the Romans had abandoned Britain to the Celts and the Saxon invaders, the tales of other warriors were woven into the text. By then, the faces of the old Celtic gods and heroes were little more than abstract patterns in the weave. And yet, in certain lights, they can still be recognized.

In early medieval legends, the beleaguered king who chooses Dinas Emrys as his fortress is not Caratacus but the British warlord Vortigern, forced by the Saxons to flee to the remote west. This would have happened four hundred years after the time of Caratacus. Vortigern’s ‘magi’ – a common medieval Latin translation of ‘Druids’ – instruct him to build a citadel. The masons start work, but, every night, the towers mysteriously collapse. The magi then advise Vortigern to ‘find a fatherless boy, kill him, and sprinkle the citadel with his blood’. The sacrificial boy turns out to be the orphaned son of a Roman nobleman. His name is Ambrosius (in its native form, Emrys) or Ambrosius Aurelianus.* The boy escapes death by revealing the true cause of the towers’ collapse: underneath the fort, inside the hill, there is a pool in which two dragons lie buried.

The legend of the Roman boy whose blood was to protect the citadel is reminiscent of one of the ‘cruel and horrible rites’ of the Druids (p. 250). During their nine-year campaign, the forces of Caratacus would have acquired prisoners and hostages, and the son of an important Roman may well have served as a blood offering before the battle. His name preserves the religious significance of the sacrifice: ‘Ambrosius’ means ‘immortal’, and ‘Aurelianus’ comes from ‘aureus’ (the adjective means ‘golden’ and was commonly applied to the sun).

On the eve of the battle at the sacred hill fort where Lludd had buried the dragons and where three solar paths converge, the ‘Immortal Sun’ was symbolically interred. A treasure, later said to be the Throne of Britain or the gold of Merlin, was entombed beneath the hill or in the nearby lake, just as the gold of Delphi had been deposited in the pools of Tolosa (p. 174). The belief in reincarnation was one of the principal tenets of the Druids; it was subsequently expressed in the legend of King Arthur and his sleeping knights, and in the stories of a saviour crucified by the Romans who descended into hell and ascended into heaven. One day, the warriors of Caratacus who died in battle would rise again like the sun in the eastern sky.

On the gentler slopes of the hill, Caratacus ‘piled up stones to serve as a rampart’, but, says Tacitus, ‘the rude and shapeless stone construction’ was swiftly demolished by the Romans. Perhaps this is the historical origin of Vortigern’s crumbling citadel. The Britons, caught between the legionaries and the auxiliaries, were overwhelmed. The wife and daughter of Caratacus were captured; his brothers surrendered. Caratacus himself escaped to the north-east, where the queen of the Brigantes, Cartimandua, hoping to tighten her delicate hold on power, handed him over to the Romans. From northern Britain, Caratacus crossed the conquered land in chains. It would have taken over a month to reach Rome, and on that long journey through Britain, Gaul and Italy, there would have been plenty of time to compose the speeches that would save him and his family from execution.

The tribes of South Wales fought on, inflamed by a report that governor Ostorius Scapula had called for the very name of the Silures to be ‘utterly extinguished’. The island of Mona was left to its own devices for another nine years. It was not until AD 60 that the soldiers of Suetonius Paulinus crossed the Menai Strait, massacred the Druids, and set about the unsoldierly task of extirpating groves of oak. But even then, their victory was incomplete. While they desecrated the Druids’ groves in the far west of Britain, where the dying sun turned the ocean red, news reached them from the mainland that a great fire was rising in the east. The whole province of Britannia was in revolt. This time, the military application of Druidic science would have devastating consequences for the Romans.

While Suetonius Paulinus was rushing from Mona towards Londinium ‘amidst a hostile population’, a messenger arrived with an order for the camp prefect of the Second Augustan Legion, based at the fortress of Isca Dumnoniorum (Exeter). The prefect would normally have been third in command, but the Mona campaign had left the fortresses undermanned, and Poenius Postumus found himself in sole charge of the legion. He was ordered to proceed immediately to the province and to join forces with Suetonius Paulinus.

For some reason, the camp prefect disobeyed the order. Between Isca Dumnoniorum in the far south-west and the Roman province in the east lay the hill forts of the Durotriges, the most impressive of which was Maiden Castle near Dorchester. Seen from the air, its mazy earthworks resemble the knotted oak-wood swirls of Celtic art, which suggests that they served an apotropaic as well as a practical, strategic purpose. Traces have been found at Maiden Castle and other forts in the region of hand-to-hand fighting and ballistic assault. While the evidence is often associated with the invasion of AD 43, many of the signs of destruction are more consistent with a date of AD 60–61. If Poenius Postumus failed to join his commander, it was probably because he, too, had a rebellion on his hands.

The attack on Mona had sparked off two simultaneous revolts – one in the south-west, extending perhaps as far as Noviomagus (Chichester) and Venta Belgarum (Winchester), the other in the south-east, affecting an area of about ten thousand square kilometres. Seventeen years after the Roman invasion, the British tribes must have retained a message system as efficient as that of the Gauls. ‘Secret conspiracies’ had been hatched by the Iceni, the Trinovantes and their allies. Now, the gods themselves appeared to be taking a hand.

The Roman merchants and administrators who had settled in Camulodunum (Colchester) were unnerved by strange occurrences. A statue of Victory was found flat on its face, as though it had been fleeing from the enemy. ‘Frenzied women’ screamed prophecies of destruction in the streets. As though in confirmation, a ruined city was seen in the waters of the Thames Estuary. In the English Channel, the flood tide ran blood-red, and the ebb tide revealed ‘effigies of human corpses’. The witches of Camulodunum, like the torch-waving Druidesses of Mona, could strike fear into a Roman heart, and the most disturbing news of all was that the rebel leader was a woman.

Boudica, queen of the Iceni, whose name means ‘Victorious’, is the first heroine of British history. Every modern retelling of her tale mentions the rape of her daughters and the whipping she received at the hands of the Roman administrators who were bleeding the province dry. The only evidence for these outrages is Boudica’s rabble-rousing speech to her troops, reported (or invented) by Tacitus. The sexual humiliation of the Icenian royal family was supposed to explain how a woman – albeit one ‘possessed of greater intelligence than often belongs to women’ (Cassius Dio) – came close to reconquering a Roman province. Boudica’s bloody rampage through southern Britain showed what could happen when a Celtic woman’s righteous passion was unleashed. It hardly needs saying that to wreak comprehensive destruction on several major settlements within a short period is impossible without a well-coordinated and well-supplied military campaign. Boudica was a soldier and a politician. The rape of the princesses and the scourging of the queen may well have taken place, but they also belong to the rhetoric of rebellion, and they provided the Celtic troops with a casus belli more inspiring than the financial malpractice of Roman officials.

The most obviously Druidic detail is missing from many popular accounts of Boudica’s meteoric career, either because it seems too weird to be true, or because it sits awkwardly with the image of Boudica as a mother and a victim of Roman male aggression. Boudica addressed her troops, according to Cassius Dio, in a ‘harsh voice’, from ‘a tribunal made out of marshy [or ‘fenny’] earth’. She wore a tartan tunic and a thick cloak. A mass of auburn hair fell to her hips. In her lap, a throbbing creature waited to be released from its prison. The queen opened her arms, and a hare bounded off in a direction which the Druids proclaimed to be auspicious.

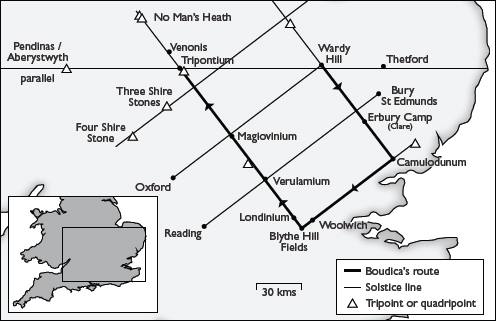

The brown hare (Lepus europaeus) will flee in a straight line for a kilometre or more, and usually in the same direction as the wind, which made it the ideal choice of animal for a Celtic commander who wanted to convince her troops that the gods agreed with her plan. The likeliest location for this ceremony of divination is the fortified settlement of Wardy Hill in the Isle of Ely, where the easterly line of longitude meets the Pendinas line of latitude and the solstice line from Oxford (fig. 62). The ‘hill’ rises no more than ten metres above sea level, but in the Cambridgeshire fens it occupies a commanding position. Excavations in the early 1990s showed that Wardy Hill was an important defensive site long before a pillbox was erected on its summit in World War Two. It was a major settlement of the Iceni tribe: ‘a resident élite persisted here’, even during the Roman occupation.

Traced on the map of Middle Earth, Boudica’s ‘rampage’ is a perfectly coordinated dance of destruction. The solstice line from Wardy Hill runs as straight as a brown hare to Erbury (or Clare) Camp, which was one of the largest fortresses of the Iceni’s allies, the Trinovantes. It then arrives at the ceremonial centre of Camulodunum. This was the capital of the Roman province and the first town to be destroyed by Boudica’s army. The Romano-Celtic temple is thought to have pre-Roman origins. This now seems all the more likely since the temple is aligned on the British solstice angles: one axis coincides with the solstice line from Wardy Hill; the other points directly at the next place on Boudica’s itinerary: Londinium.

A layer of burnt debris from the time of Boudica’s revolt has been found at several sites in London. It extends south of the Thames to Southwark, where Boudica is assumed to have crossed the river. At this point, when this book was in rehearsal, the map of Middle Earth appeared to be in error: if Boudica followed the solstice line south-west from Camulodunum, she would in fact have crossed the Thames several kilometres downstream, at a site of no apparent interest, where the Woolwich Power Station once stood. Then a bulletin arrived from the archaeological front line. Because of ‘the constant threat from treasure-hunters’, the discovery had been kept secret since 1986. Now, in 2010, with the completion of the Waterfront Leisure Centre car park, the Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit could reveal that ‘a major fortified Iron Age settlement’ had been discovered on the Woolwich Power Station site:

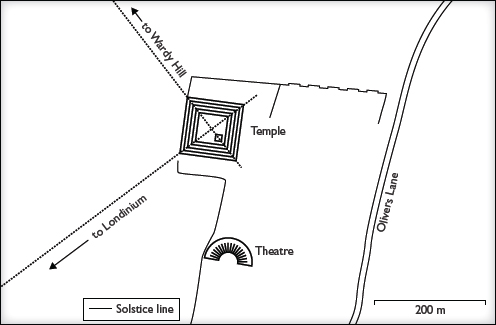

70. Camulodunum

The religious centre of Camulodunum, near Gosbeck’s Farm, Colchester. (After Dunnett and Reece.) The alignments are accurate to within less than one degree.

Constructed about 250 BC, centuries before the foundation of the City of Londinium by the Romans, this major site on the south bank of the River Thames controlled the river for over 200 years. [Its inhabitants] lived surrounded by massive earth ramparts and deep defensive ditches. . . . The complete defensive circuit would have enclosed an area of at least 15–17 acres. . . . This major riverside fort . . . also dominated a wide area and was effectively the capital of the London Basin for part of the Iron Age.

71. The pattern of Boudica’s revolt

The solstice line from Camulodunum exactly bisects this ‘capital of the London Basin’. Passing to the south of Greenwich Park, the line continues to a solar intersection and a Roman road junction at the foot of Blythe Hill Fields in Lewisham. From the top of the hill, the scouts of Boudica’s army would have looked down towards the merchant ships and barges, and the new Roman houses on the north bank of the Thames. They now turned to follow the trajectory of one of the Four Royal Roads of Britain – the road later known as Watling Street.

Along that ancient path protected by the gods, they slaughtered their way into Londinium, perhaps re-crossing the Thames at Southwark – or, if they followed the solstice line exactly, between Blackfriars Bridge and Waterloo Bridge, where a rare Celtic parade helmet with two bronze horns was dredged from the river in 1868. Their route would have taken them by Russell Square and Euston Station (not the neighbouring King’s Cross, where a local legend places the grave of Boudica), then over Hampstead Heath and along the Great North Way to the next Roman town to be destroyed – the former capital of the Catuvellauni, Verulamium (St Albans).

72. Watling Street

The presumed survey line and actual route of Watling Street. The course of the road through London is unknown. Beyond London, this line would have reached the south coast near Hastings. It matches the survey zone of the eighteenth-century London-to-Hastings road via Lewisham, Bromley, Farnborough, Sevenoaks, Tonbridge, Lamberhurst and Robertsbridge. This road is not currently identified as Roman.

With the smoking ruins of three centres of Roman power behind her, Boudica may have been intending to complete the pattern of destruction by returning to Icenian territory along the solstice line from Oxford (fig. 71). Meanwhile, after abandoning Londinium to its fate, the troops of Suetonius Paulinus had regrouped somewhere to the north of Verulamium. The camp prefect having failed to arrive from Isca Dumnoniorum with the Second Augustan Legion, the Romans were outnumbered, but a battle had become inevitable. They faced the Britons from a narrow pass with woodland in the rear and a plain in front. (These are the only topographical details given by Tacitus.) The soldiers who had recently been scared witless by the Druids of Mona had to be encouraged by Suetonius to ignore the appalling din of war-trumpets and ‘empty threats’ (Druids’ curses). ‘You see before you more women than warriors,’ he told them in an ill-advised attempt to steady their nerves.

Since Watling Street was the main artery between Wales and London, the battle is plausibly referred to as the battle of Watling Street. The exact site is unknown. The archaeologist who excavated the settlement of Tripontium on Watling Street near Rugby suggested in 1997 that the battle took place on the nearby Dunsmore Plain. This happens to be one of the battlefields recently identified by ‘terrain analysis techniques’, and the even more recent Druidic analysis agrees.

The Pendinas / Aberystwyth line of latitude bisects Watling Street at Tripontium and the meeting point of three counties, just to the east of the Oxford meridian (figs. 71 and 72). Until 2007, the site was occupied by the giant masts of radio transmitters, which made excavation impossible. A vast housing estate is about to bury whatever evidence remains. Perhaps, one day, a Celtic sword or a Roman lance will be forked out of a garden in Boudica Avenue or Suetonius Close. Any human remains may well be female. The Roman soldiers surged out of the pass in a wedge formation. Hampered by their wagons and baggage, the Britons were unable to retreat, and ‘our soldiers’, says Tacitus, ‘did not refrain from slaying even the women’.

According to Tacitus, who liked to present his pampered Roman readers with the spectacle of barbarian stoicism, Boudica committed suicide by taking poison. In the mopping-up operation, the Romans ‘laid waste to’ the lands of ‘tribes that were hostile or unreliable’.* In Cassius Dio’s less heroic account, Boudica survived the battle but fell ill and died. Her soldiers had been ready to fight on, but the death of their queen struck them as the final defeat. They gave her ‘a costly burial’, and then ‘scattered to their homes’.

No mention of this is made in the historical accounts, but a painstaking excavation has shown that at about that time the great ceremonial enclosure of the Iceni at Thetford in Norfolk disappeared. It lay on the same line of latitude as Pendinas, Tripontium and Wardy Hill. The entire complex – its grand circular buildings and nine concentric palisades – was systematically dismantled by Roman soldiers. The oaks were extracted from their postholes by digging or by pushing and pulling. The Thetford complex was neither a military nor a residential site, but the Romans had learned to fear the Druids and their oaks, and it was safer to remove them altogether than to consign the sacred place to flames from which the trees might rise again.

Ten years after the death of Boudica, most of what is now England was under Roman domination. Wales hung on to its independence until the mid-70s, and, despite the earlier massacre of Druids, the island of Mona held out even longer. In AD 78, a new governor, Gnaeus Julius Agricola, finally completed the cleansing operation from which Suetonius had been recalled by Boudica’s revolt. The Britons ‘sued for peace and surrendered the island’. With the Druids’ threat annihilated, Agricola was free to move north, to encounter ‘new peoples’, and to ‘lay waste to their lands as far as the Tay’. By AD 83, only the tribes of northern Caledonia were unsubdued.

One night, somewhere beyond the Firth of Forth, while the soldiers of the Ninth Legion slept in their camp, the sentries were butchered by ‘Caledonian natives’ and the camp was overrun. Agricola arrived during the night with the cavalry. By dawn, the Britons were fleeing through ‘the marshes and the woods’. Nothing further is reported until the following summer, when Agricola learned of the death of his baby son in Rome, and decided to seek ‘a remedy for his grief in war’. He sent the fleet ahead with orders ‘to plunder several places and to spread terror and uncertainty’.

‘Still buoyant despite their earlier defeat’, the Caledonian tribes demonstrated the characteristic Celtic ability to swarm like honey bees when the hive is attacked: ‘By embassies and treaties, they called forth the whole strength of all their states.’ More than thirty thousand warriors began to mass at a place whose name, in its Latin form, was Mons Graupius.

This is the first occasion on which a proto-Scottish nation appears in history. Unfortunately, the first named event in the annals of Scotland has been condemned to wander homelessly about the map: the location of ‘Mons Graupius’ is a mystery. There are currently about thirty contenders, but since the human geography of Iron Age Scotland is largely conjectural, and since most ancient battles leave few physical traces, no single place has emerged as the favourite.*

The name ‘Graupius’ is always said to be obscure, despite the fact that the Celtic word ‘graua’ is found in dozens of place names. It meant ‘gravel’, and the second part of the name is probably its frequent companion: ‘hill’ or ‘summit’, from the Celtic ‘penno’, the Latin forms of which are ‘pennius’ or ‘pen(n)is’. Gravelly hills are not exactly rare, but with Tacitus’s description of the battle site, a map of contemporary Roman forts, and, crucially, the Druidic map of Britain, the last stand of the British Celts can at last find a home and perhaps a monument more fitting than the planned seventeen wind turbines on the nearby Nathro Hill.

Lines of latitude divided the ancient world into klimata. One line passed through Delphi, another through Châteaumeillant, and another through Pendinas above Aberystwyth. The next line in the sequence, one hour of daylight north of Pendinas, crosses Scotland from Ardnamurchan Point in the west, by Rannoch Moor and the north shore of Loch Tummel, to Montrose Basin in the east.† The harbour of Montrose lies a day’s sail north of the probable site of the Roman naval headquarters, Horrea Classis (‘granaries of the fleet’) in the Firth of Tay. A few kilometres inland, the great meridian that runs almost the entire length of Britain intersects the Montrose parallel on the river plain below one of the most spectacular and least-known sites of Iron Age Scotland.

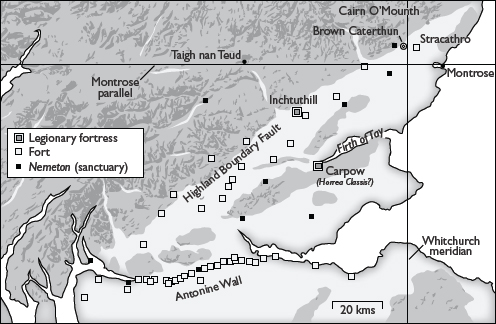

73. Central Caledonia

Central Caledonia at the time of the battle of Mons Graupius.

The twin hills called White Caterthun and Brown Caterthun were major Iron Age forts. Both were ‘multivallate’ (with several concentric ditches and ramparts). Brown Caterthun is the closer of the two to the meridian and the meeting point of two counties and two parishes. The track to the summit leaves the rich farmland of Strathmore and rises gently through the springy heather, cutting through the mounds that were once the footings of ramparts. The water that gushes from a spring at the top of the hill has carved a thin gulley through the black loam, exposing the sandstone gravel that lies just beneath the surface.

Even on a hazy day, the luminous logic of the site appears as on a relief model in a museum. In the plain below, two battles were fought in the Middle Ages. In 1130, an invading army of five thousand was defeated by David I of Scotland. In 1452, the rebel Earl of Crawford was defeated by a royalist coalition of clans from the north-east. More than a thousand years before, the intimidating sails of Agricola’s fleet might have been seen on the sparkling horizon. Between Brown Caterthun and the harbour, the buildings of Stracathro Hospital mark the site of the legionary fortress that was once the most northerly permanent outpost of the Roman empire.

It is easy to see why the Romans felt that they had come to what Tacitus calls the ‘terminus Britanniae’. The line of Roman forts runs diagonally along the Highland Boundary Fault until it reaches Stracathro. Looking north from the summit of Brown Caterthun, when the cloud-battalions part and the sun rushes over the moorland, there is a magnificent panorama of another country. This is where the Highlands and a military commander’s nightmare begin. As Tacitus has the British leader Calgacus say in his pre-battle speech: ‘There are no nations beyond us – nothing but waves and rocks.’

The Caledonians arranged themselves with their front line on the plain and the other ranks rising up the slope of the hill in tight formation. Eight thousand Roman foot soldiers and three thousand cavalry took up position in front of the camp. ‘The flat country between was filled with the noise of the [British] charioteers racing about.’ Until the very last minute, young men and old warriors had been arriving from regions unknown to the Romans. Since the valley sloping down towards the Firth of Clyde in the west was occupied by Roman forts, the warriors would have reached the battleground by the high roads from the north and by the Cairn O’Mounth pass, which had been a portal to the Highlands since prehistory.

The battle at the end of Middle Earth was a triumph for the tactical brilliance of Agricola. His grief found a powerful remedy: ten thousand Britons fell; ‘equipment, bodies and mangled limbs bestrewed the bloody earth’. The remaining twenty thousand turned and ran ‘in disarray, without regard for one another, scattering far into the trackless waste’. After the battle, a strange custom of the vanquished was observed: many of the fighters set fire to their homes and slaughtered their own wives and children. That night, beyond the camp where the Romans celebrated the victory and their plunder, the wind brought the sound of men and women wailing ‘as they dragged away the wounded or called to the survivors’. At daybreak, victory showed its true face:

An enormous silence reigned on every side. The hills were desolate, smoke rose from distant roofs, and the scouts who were sent out in all directions encountered not a soul.

The survivors had vanished as though the battle were already a legend. Agricola returned to winter quarters and received the report of his naval commanders, who had sailed around the north of Caledonia, thereby contributing valuable information to the Romans’ knowledge of the world. The tribes of remotest Britannia were left in peace to fight among themselves, while, a long way to the south, in their shiny new towns, the Romanized British enjoyed luxuries such as couches and chairs, red Samian ware, colourful rings and trinkets in the fashionable Celtic style, and oil-lamps made in Italy and Gaul.

The olive oil that was used as lamp fuel was expensive to import, but for the few who could afford it, the oil was worth its weight in gold. That gleaming nectar of the warm Mediterranean made it possible to cheat the sun and to stay up far into the night, drinking wine and telling tales of Caratacus and Boudica, and of the days when the sun god had come to earth and made it safe for mortal beings.

* Few of the other traditional candidates fit Tacitus’s description: Caer Caradoc near Church Stretton (a negligible river, and in Cornovian rather than Ordovican territory; the name ‘Caradoc’ is a corruption of ‘Cordokes’); Caer Caradoc near Clun (a negligible river); Llanymynech (where advance and retreat would have been relatively easy); the Herefordshire Beacon or British Camp (no river). The most likely sites, apart from Dinas Emrys, are Breidden Hill and Cefn Carnedd, both above the river Severn.

* This was the name of a Romano-British chieftain. The later version, by Geoffrey of Monmouth, identifies the boy as the mathematician, astronomer, bard and prophet, Myrddin or Merlin.

* The participle, ‘vastatum’ (‘ravaged’), may indicate a deliberate depopulation of tribal territories.

* The battle may have been fought somewhere in the Grampian Mountains, but the name ‘Grampian’ is a false clue: it was first applied to the mountains of the southern Highlands by a sixteenth-century Scottish historian whose Latin text misspelled ‘Graupius’ with an ‘m’.

† By an inscrutable coincidence, this line of latitude passes close to a small white house on the outskirts of Pitlochry at the foot of the Pass of Killiecrankie called Tigh na Geat (formerly, Taigh nan Teud, or ‘House of the Harpstring’). The house was once said to mark the southerly limit of the Lords of the Isles’ influence and the exact centre of Scotland.