The twenty thousand who fled from Mons Graupius vanished into a land of which very little is known. A century after Agricola, the Romans had pulled back behind Hadrian’s Wall, and Caledonia was once again a land of myth. In the early third century, Cassius Dio described a hardy race of Caledonians living off roots and bark, and capable of surviving for days on end in swamps with only their heads above water. The only reliable sighting of the northern Caledonians is in Tacitus’s account of a renegade cohort of German auxiliaries in Agricola’s army. After killing a centurion and some soldiers, they hijacked three galleys and set off on ‘a grand and memorable exploit’. They, rather than Agricola’s admiral, are the first people known for certain to have sailed around the north of Britain. Provisions exhausted, they went inland in search of water and food, and ‘encountered many Britons who fought to defend their property’. Some of the Germans eventually returned, as slaves, to the Rhineland, where ‘their tales of the extraordinary adventure made them famous’.

The Caledonians themselves, having ‘red hair and long limbs’, were considered by Tacitus to be Germanic in origin. Since the German tribes had no Druids, this might explain why, in vivid contrast to southern Britain, there are few signs of a solar network in Caledonia. Even if the angles are adjusted to more northerly climes, any hypothetical solstice lines are as indistinct as shadows on a sunless day.

The map of Middle Earth reflects a cultural divide: it suggests a sphere of Druidic influence in the parts of Britain closest to the Continent which had been colonized by Belgic tribes. In the early Middle Ages, Britain was conventionally divided into north and south by an imaginary line running west from the Humber Estuary, following what would have been the old southern borders of the Brigantes. North of the line, in the kingdom of North-Humbria, the pan-tribal authority of the Druids may never have been recognized. When Caratacus the Catuvellaunian had thrown himself on the mercy of the Brigantian queen, Cartimandua, no Druidic council had prevented her from handing him over to the Romans.

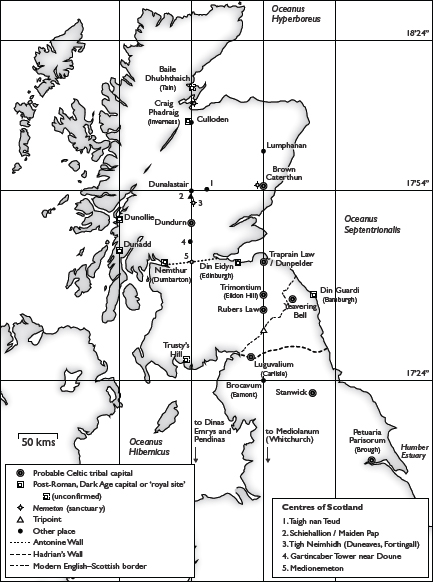

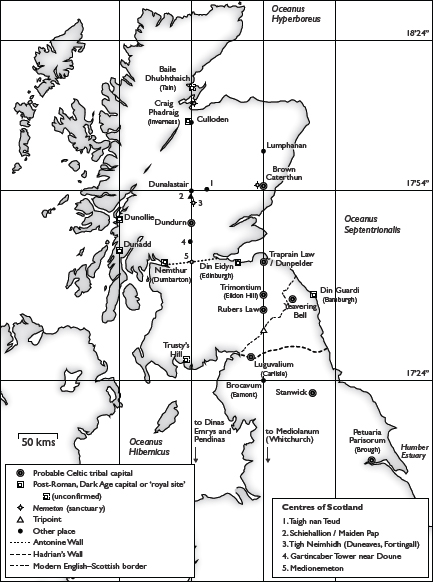

The territory that is now Scotland had no perceptible Heraklean Way or Royal Road, and yet the Caledonian tribes seem to have known where they were in relation to the rest of the world. Some of their capitals lie on the Whitchurch meridian (p. 240), others on the meridian that passes through Dinas Emrys and Medionemeton, and still others on a third line of longitude that runs through the western Highlands. Whatever their ethnic origins, the names of these tribes are clearly Celtic,* and so is this alignment of centres of power on the meridians.

There are no equivalents of the myth of Lludd and the dragons to provide a clue to a Caledonian omphalos, only untraceable local traditions which purport to identify the centre of Scotland. Each of these traditions identifies a different centre, but when the various sites are plotted on the map, they suddenly seem to be in harmony. One ‘centre of Scotland’ is the little white house on the Montrose parallel (p. 265n). Four others line up on the meridian which passes through Dinas Emrys. The first is the ‘middle sanctuary’ of Medionemeton. The second is Gartincaber Tower near Doune (a folly built in 1799 on a site believed to be the geographical centre of Scotland). The third is the village of Fortingall, where a two-thousand-year-old yew tree twists on its crutches in the middle of an ancient monastic site. (On the edge of the village, which is also the fabled birthplace of Pontius Pilate, a stone circle stands at a place, Duneaves, whose name comes from ‘nemeton’.) The fourth ‘centre’ on the same meridian rises behind Fortingall to the north: this is the great granite cone of the mountain called Schiehallion. Its Gaelic name – Sìdh Chailleann – means ‘Fairy-hill of the Caledonians’. In the language of lowlanders, its name was Maiden Pap, which means ‘Middle Mountain’.†

74. Centres of Scotland and the Caledonian meridians

Some capitals of Dark Age kingdoms founded after the departure of the Romans were probably the successors of Iron Age capitals. The only plausible solstice diagonal in Caledonia is the trajectory of the ‘Royal Road’ along which Boudica marched from Wardy Hill to Camulodunum. This is the longest diagonal that can be drawn through Britain. It passes to the west of the tribal capital of the Carvetii tribe, Luguvalium (Carlisle), through Brocavum (Eamont), Blatobulgium and several other Roman forts, and along the route of the A74 via Gretna Green to the site of the Glasgow Necropolis. It is shown as a dotted line in figure 79.

In the historical silence of the Highlands, it is hard to distinguish human messages from stray sounds carried by the wind. This striking alignment of ‘centres’ does all the same have a compellingly Celtic air. It suggests that Caledonia was connected to the rest of Britain and the Celtic world almost two millennia before Scotland and England were joined by the Acts of Union.

Did some memory of pagan meridians survive in bardic tales and witches’ lore? When Macbeth of Scotland made his last stand at the village of Lumphanan in 1057, he or his geomancers might have known that the battleground lay directly on the Whitchurch meridian. Successive developments over many centuries of prehistoric sites such as Stonehenge show that when tribal memory was preserved in astronomical alignments and visible features of the landscape, it could have a very long life. In 1746, the Caledonian tribes suffered a defeat even more catastrophic than the battle of Mons Graupius. Despite the marshy terrain, the Jacobite rebels chose a moor to the east of Inverness for their decisive engagement with the government army. But only a Highlander for whom a thousand years were a short spell in the collective memory of his clan would have known that Culloden Moor is bisected by the line that runs through the middle of Scotland.

From Caledonia, the sun of the winter solstice appeared to return to the Ocean beyond an island that was the last outpost of the inhabited world. The Massalian explorer Pytheas had been told that its name was ‘Ierne’. The origin of the word is unknown, though it survives in the modern name of Ireland: Eire. The Romans, having heard that ‘complete savages lead a miserable existence there because of the cold’, called it ‘Hibernia’ (‘the wintry land’). It was also said that despite the wretched climate, the grass of Hibernia was so lush and plentiful that ‘the livestock eat their fill in a short space of time and, if no one prevents them from grazing, they explode’.

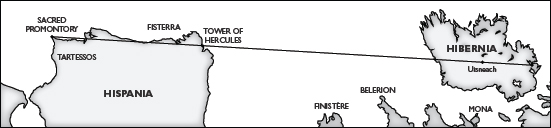

Because Ireland was never conquered by the Romans, its pastures are prolific in tales dating back to the days of the ancient Celts. They were first recorded in the early Middle Ages, but echoes of the founding myths had reached the outside world long before. In the early fifth century AD, in his History Against the Pagans, Orosius reported that ‘a very tall lighthouse’ had been erected in the city of Brigantia (A Coruña) in north-western Spain ‘for the purpose of looking out towards Britannia’.

The implicit notion that the British Isles might be visible from Spain probably reflects a tale passed on by a trader, a slave or a refugee like the deposed Irish chieftain who sought asylum with Agricola. The eleventh-century compilation of legends known as The Book of Invasions (Lebor Gabála Érenn) tells the story of Breogán, a Celtic king of Galicia, who built a gigantic tower in Brigantia. (Hearing this, a Roman would have recognized the lighthouse called the Tower of Hercules.) ‘On a clear winter’s evening’, Breogán’s son climbed to the top of the tower and saw a distant green shore. He promptly set sail with ‘thrice thirty warriors’. ‘They landed on the “Fetid Shore” of the Headland of Corcu Duibne’ in the south-west of Ireland.

These pre-Christian legends embrace so many diverse and specific details that the saga of Irish origins defies summary but not belief. If Breogán’s son sailed due north from Brigantia, he would have come to the hill of Ard Nemid in what is now Cork Harbour. This, according to Ptolemy’s Geography, was the part of Hibernia inhabited by a tribe called the Brigantes.* Perhaps the Irish Brigantes had heard of the city of Brigantia in Spain and imagined their Iberian forefathers crossing the Ocean with the stiff breeze of destiny in their sails. It is impossible to know how much historical truth the legend conveys. Some promontory forts in south-western Ireland have Iberian-style defences, and the lives of the early Irish saints contain many allusions to Iberia and Lusitania (Portugal). Archaeology suggests that Hibernia’s ties with the rest of Keltika were tenuous, but this may simply reflect the fact that so many Irish Iron Age sites have yet to be excavated. Many have been destroyed – and still are being destroyed – by road building and peat extraction. At the time of writing, the chief material proof of Ireland’s Mediterranean connections is the skull of a Barbary macaque – the species of monkey that still scampers over the Rock of Gibraltar – which crossed the Ocean, dead or alive, some time between 390 and 20 BC.

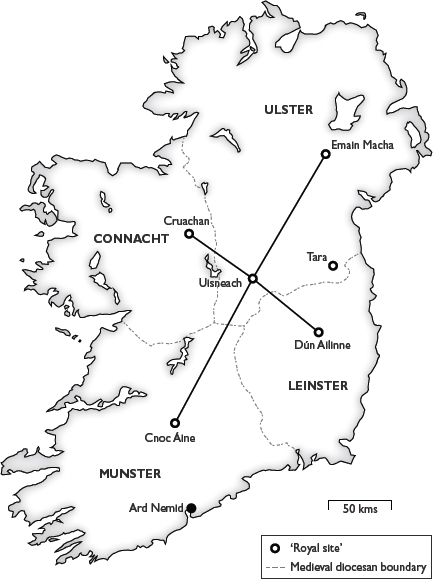

The monkey’s skull was discovered under the great burial mound at Navan Fort in Northern Ireland. Navan Fort is the Emain Macha of Irish legend, one of the ‘royal sites’ at which the early medieval kings of Ireland held assemblies and ceremonies of inauguration. The intricate earthworks and timber circles of these royal sites show that they were already the religious centres of Ireland in the Iron Age. They were chosen, like many of the oppida of Gaul, because they were known to be places that had been sacred to the pre-Celtic inhabitants of the island. One of the royal sites – the complex of barrows and enclosures on the Hill of Uisneach – is identified in legend as the omphalos of Ireland. Uisneach was the sacred centre, the burial place of Lugh, where a Druid lit the first fire in Ireland. It stood in a territory called ‘Mide’ (the Middle Land). The rest of the island was divided into four kingdoms, which became the medieval provinces of Ulster, Connacht, Leinster and Munster.

Celtic society survived for so long in Ireland that these places of legend can be seen emerging into recorded history with their identities intact. In gloating over the demise of the great pagan shrines, the ninth-century Christian author of The Martyrology of Óengus (Félire Óengusso) unintentionally produced a miniature gazetteer of Iron Age Ireland:

The mighty burgh of Temra [Tara] perished at the death of her princes: with a multitude of venerable champions the Ard mór [great height] of Machae [Armagh] abides.

Ráth Chrúachan [Rathcroghan, the ring-fort of Cruachan] has vanished . . . fair is the sovranty over princes in the monastery of Clonmacnoise.

The proud burgh of Aillinne [Dún Ailinne] has perished with its warlike host: great is victorious Brigit; fair is her multitudinous cemetery [Kildare].

Emain’s burgh [Emain Macha] has vanished, save only its stones: the Rome of the western world is multitudinous Glendalough.

The old cities of the pagans, wherein ownership was acquired by long use, they are waste without worship, like Lugaid’s House-site.

These pagan centres can be plotted on a map, and any solar patterns hidden in Iron Age Hibernia should appear. The most obviously Druidic feature is this: the omphalos of Uisneach is connected by a solstice line to the royal sites of Cruachan and Dún Ailinne. The bearings are close but not identical to the British standard (within 1.4° and 1.6° respectively). Two other royal sites – Cnoc Áine and Emain Macha – are also roughly aligned on the Uisneach omphalos, within a range of 2.2°.

75. ‘Royal sites’ of Ireland

‘Royal sites’ of Iron Age Ireland. The Hill of Tara, the seat of the kings of early medieval Ireland, plays no part in this pattern. It may have been used only sporadically, or acquired its eminence only later.

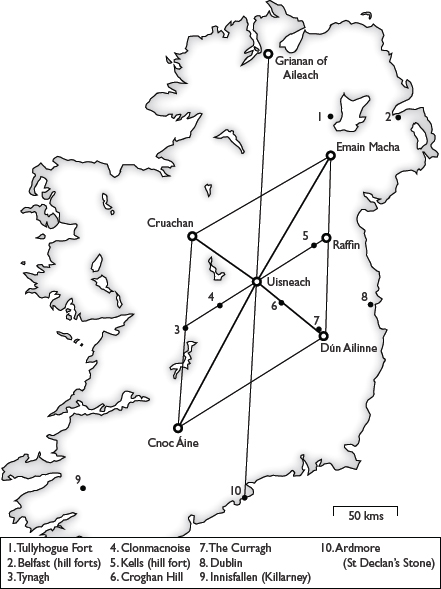

76. The Irish network

The range of bearings of the three west–east diagonals is 57.96°–59.94°. Assuming perfect alignments, the system would have been based on a tan ratio of 9:5. The line joining Uisneach to Dún Ailinne is a winter solstice line; the corresponding line to Cruachan points to sunset on 1 August (the feast of Lughnasadh).

Despite the slight inaccuracies, a pattern materializes like a piece of jewellery in an archaeologist’s trench. The fortress and ‘royal site’ of the Grianan of Aileach was one of the key coordinates used in an early division of Ireland. It lies north of Uisneach on a bearing of 2.9°. This skewed meridian is mirrored by two similarly tilted north–south lines which link the other four royal sites (fig. 76).

This peculiarly Hibernian variation on the solar network is remarkably coherent. The Uisneach meridian bisects the two diagonal lines, forming two parallelograms. Logically, a corresponding site should exist to the south of Uisneach on the line from the Grianan of Aileach. This would be Ardmore, which predates St Patrick and is probably the oldest monastic settlement in Ireland. In the nineteenth century, thousands of pilgrims were still paying their pagan devotions to a miraculous stone and a holy well at Ardmore, enacting an ‘annual scene of disgusting superstition’ involving the not-entirely-ritual consumption of whiskey.

One other ‘royal site’ remains to be accounted for: Raffin Fort in County Meath is not mentioned in the medieval texts, but it, too, ‘displays all the features typical of a royal site and is considered to belong to this group’. The solstice lines now begin to trace out a lost history of Ireland. On the same bearing as the other two diagonals – within less than one quarter of a degree – the line from Raffin Fort passes through the hill fort that became the monastery of Kells, then through the Uisneach omphalos, to the monastery of Clonmacnoise, which was one of the great centres of learning in early medieval Ireland. The westerly point of intersection lies just outside the village of Tynagh. The missionary who Christianized Tynagh was said to be a son of Lugh, which suggests that the site was once a cult centre of the Celtic god.

This elegant pattern may be further evidence of the spread of Celtic culture to Ireland by trade, migration or even deliberate inculcation. A possible sequence of events can be pieced together from legend and by analogy with other Celtic lands. The earliest partition of Ireland described in The Book of Invasions used a natural frontier, the Esker Riada. This ‘road’, formed of glacial ridges of sand and gravel, splits the island roughly into north and south. At this point in the history of Hibernia, there was no omphalos or sacred centre: the division was purely terrestrial.

Then a people called the Fir Bolg arrived after an odyssey of several generations which had taken them through Greece and Spain. It was the Fir Bolg who chose Uisneach as the centre, presumably using celestial rather than geographical measurements. The Book of Invasions describes their partition of Ireland as a ‘tóraind’ (a ‘marking-out’ or ‘delimiting’). As in Gaul, certain prehistoric sites were chosen and then redeveloped – equipped with banks, ditches, towers and palisades. If the architects of these royal sites retained some of the crude solstitial alignments of the Neolithic monuments, this would account for the inaccuracies of the Hibernian system. When the first Christian missionaries landed in Ireland, they followed in the footsteps of the Druid ‘missionaries’, and their monastic houses were the direct descendants of Druid schools.

The solar map of Ireland is as rich in virtual expeditions as a railway timetable. It no longer seems a merely picturesque coincidence, for example, that the sun of the winter solstice, seen from Uisneach, rises over Croghan Hill (no. 6 in fig. 76), where St Brigit founded the first convent in Ireland. Other places on the lines may turn out to have been centres of pagan worship, and perhaps the idiosyncrasies of the system will prove to be consequential. The strangely tilted meridian which runs three degrees west of south from the Uisneach omphalos could be the result of careful calculation. If the line is projected as it would have been on a medieval portolan chart, it arrives with eerie precision at the exact point from which Breogán’s son and his armada sailed for Ireland. When he climbed the tower in Brigantia later known as the Tower of Hercules and saw the distant green shore, his mind’s eye did not deceive him.

Like the Britons and the Gauls, the Irish developed a system which reflected their fabled origins. Archaeologists have shown that the chronology of the Irish legends is astonishingly accurate. The same precision may be encoded in the solar network. Recently, scholars have begun to talk of Celtic culture spreading, not from central Europe, but from the far west. It would have travelled along the Atlantic sea lanes from one ‘end of the earth’ to the next – from the Sacred Promontory to Fisterra and Brigantia, and from there to Finistère, Belerion and the other ‘Sacred Promontory’, on the south-eastern tip of Ireland.

The earliest written records in Europe beyond the Aegean are inscriptions made in a language called Tartessian. The oldest inscriptions use the Phoenician alphabet and date from the eighth century BC. Tartessian was spoken in south-western Iberia. If the partial decipherments are correct, this language belongs to the same sub-group as the Celtic languages of Gaul and Britain. Like the Irish legends and the lives of Irish saints, these inscriptions may be the distant echoes of an ancient maritime trading empire based on slaves and luxury goods. The rhumb line that connects the Tower of Hercules to Uisneach would represent one of the oldest trade routes in Europe. If the line is projected further still, it arrives with the same uncanny accuracy at the Sacred Promontory on the extreme south-western tip of Iberia, where the sun of the winter solstice returned to the lower world (fig. 77), and where the road from the ends of the earth began its long journey to the Alps.

Here, on the shores of the Western Ocean, another book begins. It is tempting to believe that the story of Celtic Middle Earth had a sequel, and that the Druids continued to practise and teach in the early Christian era. The fifth-century saint referred to in the Martyrology of Óengus as the ‘victorious Brigit’ (one of the patron saints of Ireland) was the daughter or foster-daughter of a star-gazing Druid who predicted that she would ‘shine in the world like the sun in the vault of heaven’. According to one account, Brigit’s father had come, like Breogán’s son, from Lusitania. Her feast day is the day of Imbolc (the first of February), one of the four Celtic festivals, and her name – ‘the Shining One’ – is that of a Celtic goddess. The woman herself, who tended a fire surrounded by a circular hedge that no man could cross, might have been raised as a priestess of her divine namesake.

The word ‘Druid’ was applied to Christian saints and hermits, and even to the Son of God. But a word is not proof of continuity. The ‘draoidhe’ who were defeated by St Patrick lived five hundred years after Julius Caesar described the Druids of Gaul as a scientific intelligentsia. The diplomat and scholar Diviciacus would have had little in common with the fifth-century Irish Druid Lucatmael, who, in a miracle-contest with St Patrick, induced ‘demons’ to cover the land in a waist-high blanket of snow.

In Continental Europe, the body of knowledge that had once demanded a twenty-year-long education was either lost or subsumed into the classical curriculum. The fourth-century Gaulish poet Ausonius claimed that ‘professores’ teaching in Bordeaux were scions of ancient Druid families, but the implication was that Druidism belonged to the past. Some of the Druids’ religious functions – consecrating temples, measuring boundaries, counselling kings – survived in pagan cults, which were absorbed rather than abolished by the Church. Their temples – according to the instructions of Pope Gregory I in c. 600 – were converted (‘if they be well built’) rather than destroyed, ‘for surely it is impossible to efface all at once everything from their strong minds’.

77. From Hispania to Hibernia

While Druidism persisted in popular religion, the art that had been the geometrical form of its wisdom went beautifully to seed. The ‘Ultimate La Tène’ style of illuminated manuscripts such as the Book of Kells (c. 800) is decorative rather than mathematical; ‘Celtic’ Christian crosses may resemble pagan sun-wheels and evoke the pattern of solstice lines radiating from an omphalos, but their geometry is inconsistent and contains no secret messages from a Druid underworld.

The intellectual decline of Celtic art is especially evident in the enigmatic carved stones of the Picts of Dark Age Scotland. Most of the carvings were made in the eighth and ninth centuries, more than a thousand years after Celtic art first appeared in Europe. One of the commonest figures in the Pictish repertoire combines the crescent-shaped ‘pelta’ of Celtic art with two ‘compass lines’, which could be the solstice bearings of a solar grid, or the finger and thumb of a measuring hand. But these, too, are inconsistent. Even after decades of scholarly study, the Pictish symbols are still mysterious, and it now looks as though they were mysterious to the Picts themselves. The intriguing designs they saw on antique pieces of equipment and jewellery were a code they were never able to crack. They copied the curiously truncated shapes, unaware that each one had once been the visible part of an invisible whole.

78. A Pictish carving

From a Pictish stone found in the Orkney Islands. (After Murray, p. 230)

When the first Christian chapels were built in Britain and Gaul, the creator of the Heraklean Way had long since ascended into the heavens. ‘Meanwhile, stiff with cold and frost, and in a remote region of the earth, far from the visible sun, these islands received the light of the true Sun – which is to say the precepts of Christ – showing to the whole world his splendour, not only from the temporal firmament, but from the height of heaven, which surpasses all things temporal.’

In Gaul, the ‘true Sun’ shone brightest where the Romans had founded their towns and where the great cathedrals would be built. But it also shone on obscure and half-abandoned places that had been sacred to the Celts. On the mountain where the oppidum of Bibracte had stood, a chapel replaced the temple. Nemetons turned into Christian shrines, and sites named after the god Lugh acquired chapels dedicated to a ‘St Luc’. At least one Mediolanum changed its name to ‘Madeleine’. In Alesia, the mother-city of the Gauls, a Christian girl was said to have been martyred in 252. St Regina (Sainte Reine) had been decapitated, and where her severed head had struck the ground, a miraculous healing spring gushed out.

The story of the saint of Alesia is typical of the early process of Christianization. The pagan gods of Alesia’s healing spring were officially obliterated in the ninth century, when a ‘Life of St Regina’ was concocted from the hagiography of another saint. Nothing was said of the battle that had been fought at Alesia in September 52 BC, though the day on which the saint is still remembered (7 September) may be the exact anniversary of Vercingetorix’s defeat. Thousands of other sites were ideologically cleared to make way for the new religion. Monasteries and hermitages were founded in places said to be so wild and barren – ‘in terra deserta, in loco horroris et vastae solitudinis’* – that only demons had been able to live there until the grace of God had made them fertile.

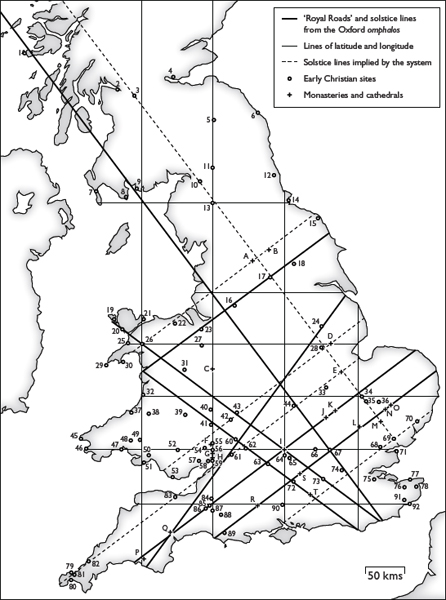

79. Christianity and the solar network

The early Christian sites (first foundation, up to the mid-seventh century) are plotted without prior reference to solstice lines. For exact coordinates, see www.panmacmillan.com/theancientpaths. In Wales, pre-eighth-century monasteries are shown. Hoards containing Christian artefacts are omitted because provenances are uncertain (Mildenhall, Traprain Law, Water Newton, etc.), as are Christian embellishments and private chapels in Roman villas. Later monasteries and cathedrals (c. 974–1248) are selected for their association with the system (e.g. those on the ‘Royal Road’ between Salisbury and Bury St Edmunds: p. 239).

Key:

Early Christian sites (list of coordinates at www.panmacmillan.com/theancientpaths): 1. Iona. 2. Dumbarton. 3. Glasgow (Govan). 4. Dunfermline. 5. Mailros (Melrose). 6. Lindisfarne. 7. Kirkmadrine. 8. Whithorn. 9. Ardwall Isle. 10. Carlisle. 11. Bewcastle. 12. Jarrow. 13. Eamont. 14. Hartlepool. 15. Whitby. 16. Manchester. 17. Leeds. 18. York. 19. Caergybi. 20. Aberffraw. 21. Penmon. 22. St Asaph. 23. Chester. 24. Lincoln (St Paul in the Bail). 25. Clynnog Fawr. 26. Dinas Emrys. 27. Bangor on Dee. 28. Ancaster. 29. Bardsey. 30. St Tudwal’s Island East. 31. Meifod. 32. Llanbadarn Fawr. 33. Ashton. 34. Ely. 35. Soham. 36. Icklingham. 37. Llanarth. 38. Llanddewi Brefi. 39. Glascwm. 40. Leominster. 41. Hereford. 42. Malvern (St Ann’s Well). 43. Worcester. 44. Bannaventa. 45. St Davids. 46. St Brides. 47. Coygan Camp. 48. Carmarthen. 49. Llanarthney. 50. Llangyfelach. 51. Bishopston. 52. Merthyr Tydfil. 53. Llantwit Major. 54. Raglan. 55. Dixton. 56. Llandogo. 57. Caerleon. 58. Caerwent. 59. Mathern (St Tewdric’s Well). 60. Gloucester (Churchdown Hill). 61. Uley. 62. Bagendon (church in oppidum). 63. Dragon Hill, Uffington (chapel). 64. Abingdon. 65. Dorchester-on-Thames. 66. Cholesbury. 67. St Albans. 68. Witham. 69. Colchester. 70. Sutton Hoo (?). 71. Bradwell (Othona). 72. Silchester. 73. Chertsey. 74. Westminster. 75. Rochester. 76. Canterbury. 77. Reculver. 78. Richborough. 79. St Ives (St Ia’s). 80. St Michael’s Mount. 81. Phillack. 82. Perranporth (St Piran’s Oratory). 83. Carhampton. 84. Glastonbury Tor (St Michael’s). 85. Bradley Hill. 86. Muchelney. 87. Ilchester. 88. Sherborne. 89. Poundbury (Dorchester). 90. Winchester. 91. Lyminge. 92. Folkestone (St Eanswythe).

Monasteries and cathedrals (selected): A. Bolton Priory. B. Fountains Abbey. C. Haughmond Abbey. D. Haverholme Priory. E. Croyland Abbey. F. Monmouth Priory. G. Tintern Abbey. H. Chepstow Priory. I. Osney Abbey. J. Newnham Priory (Bedford). K. St Neots Priory. L. Walden Abbey (Saffron Walden). M. Clare Priory. N. Bury St Edmunds Abbey. O. Ixworth Priory. P. Plympton Priory. Q. Exeter Abbey. R. Salisbury Cathedral. S. Reading Abbey. T. Waverley Abbey.

In the long dawn of western Christianity, older landscapes sometimes deepen the view like anachronisms in a dream. When St Columba and St Patrick processed ‘sunwise’ around chapels and holy wells, they were performing a Druidic ritual in the name of a new god. (As the native of a nemeton,† Patrick may well have been familiar with Druidic rites.) In the curved ambulatories of their churches, monks paced out the invisible ellipses of Celtic temples. Pope Gregory had instructed that animal sacrifice should be allowed to continue, provided that the animal be eaten afterwards in a holy feast and ‘no longer sacrificed as an offering to the devil’. Many other ceremonies must have been retained, even as their meanings were erased.

Traces of this merging of two religions are surprisingly evident in the British solar network. Several major Christian sites are strung along the Whitchurch meridian like beads on a rosary: Mailros Abbey, Lanercost Priory, Tintern Abbey, Chepstow Priory, the monasteries of Llandogo and Dixton near Monmouth, the church on Glastonbury Tor, and the ancient chapel at Eamont near Penrith, where the kings of Dark Age Britain accepted Christianity as the official religion of the Isles in 927.

Apart from the lonely church on the Bewcastle Waste in Cumbria, which the Romans knew as ‘Fanum Cocidi’, the shrine of a Celtic god, these holy places seem to have been created ex nihilo. Yet they and many others adhere to the British solstice lines as though, along with some of the Iron Age tribal boundaries, knowledge of the system had somehow been preserved.

Evidence of the first Christian sites in Britain is sparse and not always easy to interpret. It consists of saints’ lives and chronicles, inscriptions, lead fonts and other ecclesiastical remains, and cemeteries in which the skeletons are oriented on the sunrise. Far more is known about the great abbeys and priories of the monastic revival of the tenth to twelfth centuries, but there are no documents to explain why they, too, often match the solar paths. Monastic histories were stitched together from fictional accounts of the abbey’s patron saint, forged charters and snippets of folklore, suitably Christianized. No ambitious institution would have advertised its pagan roots. When Osney Abbey was founded as a priory in 1129 on sodden meadows beneath Oxford Castle, no reference was made to the site’s legendary status as the omphalos of Celtic Britain. The unpromising location was selected because the founder’s wife liked to walk along the riverbank and often stopped by a tree in which – miraculously, it seemed to her – magpies used to gather ‘and ther to chattre, and as it wer to speke onto her’. The garrulous birds, her confessor explained, were souls in purgatory seeking rest. Accordingly, the priory was built on that very spot.

Abbeys, priories and even hermitages were founded where they would be fed by the flow of pilgrims’ money. They stood where people had passed or congregated in pagan times. Travellers’ tales and local legends were incorporated into the founding myth. Monks and abbots, too, believed in witches and demons; they knew and feared the names of the pagan gods. Their mental maps of the abbey’s environs included magic wells and trees, and the mounds where fairies went to and from the lower world. Some of the medieval abbeys were joined to other holy sites by straight tracks called ‘fairy paths’, ‘trods’ or ‘corpse roads’. These tracks were said to have been made by the feet of saints or angels. Some were remnants of longer routes such as the Icknield Way, and although the paths were prehistoric, Christian pilgrims walked along them towards a new life with the sun’s light in their eyes or their shadows rushing ahead to the horizon.

This is the mystery glimpsed in the scriptorium at St Albans: the solstice line labelled ‘Icknield Way’ on the map of the Four Royal Roads passes through five abbeys and one cathedral (Salisbury), despite the fact that most of those institutions had existed for less than a century. How did a new cathedral come to find itself on an ancient solar path? The mystery would be impenetrable without a legend which explains how the site was chosen. From the top of the old cathedral inside the circular earthworks of the Iron Age oppidum three kilometres to the north, the Bishop of Old Sarum or his bowman shot an arrow. Where the arrow landed, the new cathedral would be built. Instead of falling to the ground, the arrow pierced a deer, which ran to the banks of the river Avon. It died, somewhat inconveniently, on a marshy floodplain, on the site of the future Salisbury Cathedral.

The deer’s sense of direction in the throes of death was as keen as that of Boudica’s hare. It died on a piece of land called Myrfield or ‘boundary field’ at which three ancient territories met. This zoomantic divination practised or sanctioned by a medieval bishop is one of the rare clues to an actual process of transmission. Druids, too, deciphered messages in the struggles of slain animals. Whether or not they grasped the whole picture, hermits, seers and pagan worshippers ensured that the sacred places of the new religion would be aligned, like its altars and graves, on the paths of the old sun. Hermits colonized Druidic sites, and on those sites, abbeys were founded – which is why, when St Patroclus of Bourges made his cell ‘in the deep solitudes of the forest’ in the early sixth century, his secluded retreat already had a Celtic name: Mediocantus or ‘Middle of the Wheel’. In churches standing on the foundations of temples, and in basilicas built from the rubble of oppida, half-converted congregations heard words of wisdom very similar to those they had learned from the Druids:

‘Honour the gods, do no evil, and exercise courage.’

‘Death is but the middle of a long life.’

‘Souls do not perish but pass after death from one body into another.’

More than a thousand years after the advent of the Celtic gods, their sun was still shining on the mortal earth. All over Europe, pilgrims followed the roads that could be concealed but not destroyed. The new religion was spreading its own map over the world, and although the sacred centre was now Jerusalem and many of the coordinates of the Celtic earth had been erased, certain places that had fallen into obscurity recovered some of their ancient glory. Every year, hordes of Christians passed through Châteaumeillant, the omphalos of Gaul, heading south-west to the Pyrenees and the shrine of the apostle James at Compostela. They imagined themselves to be guided by the blur of the Milky Way, which is still known in some parts as ‘the Way of St James’. The white road in the heavens had once been associated with Herakles and his mother’s milk, and with the glowing trail that was left by the dying sun as it descended towards the Ocean.

Half an hour of daylight south of Châteaumeillant, beyond the mountain forests that Herakles had turned into the world’s biggest funeral pyre, the latitude line of the northern Mediterranean leads to Santiago de Compostela and, from there, to the End of the Earth called Fisterra. The ‘Altar of the Sun’ vanished long ago. It may have stood on the hill above the lighthouse or on the site of the twelfth-century church of Santa María das Areas, where pilgrims still pray to a miracle-working Christ of the Golden Beard.

Centuries before, Carthaginian vessels had passed the Altar of the Sun as they sailed north on the tin route to Finistère and Belerion. The rocky headland on the Costa da Morte was the scene of many shipwrecks, and treasures may still be awaiting rediscovery beneath the Atlantic storms. According to the legend of the Fisterran Christ, a statue with a golden beard was cast into the waves from a ship in distress, to lighten the load or to calm the raging winds by propitiation. For an unknown length of time, it was lost in the Ocean. Then, one day, it was caught in a fisherman’s net. Like many other images of ancient gods, it was interpreted as a miraculous image of Christ. But a golden beard had been one of the attributes of the Carthaginian Herakles. He could still be seen in all his splendour in the fifth century, on the African shores of the Mediterranean, before Christians removed his beard and felled his mighty trunk. His ritual death, in an ancient storm at the end of the earth, was the god’s salvation. He plunged, like the sun and the souls of the dead, into the roaring sea, and the ship that had carried him sailed on in the certain knowledge that light would soon be spreading from the east.

* Caereni, ‘Shepherds’; Caledones, ‘People of the Rugged Fortress’; Carnonacae, ‘Hornèd Ones’; Cornavii, ‘Sailors’; Damnonii, ‘People of the Lower World’ or ‘Keepers’ or ‘Magistrates’; etc. The tribes are listed in Ptolemy’s Geography (second century AD), probably from information supplied by Agricola’s officers.

† ‘Pap’, meaning ‘nipple’ or ‘breast’, was a common name for a hill. ‘Maiden’ is incorrectly assumed to refer to the mountain’s fancied resemblance to a virgin’s breast.

* Names derived from ‘briga’ (‘high place’) are common in the Celtic world, especially in Iberia. There is no known connection between this tribe and the Brigantes of Britain.

* Deuteronomy, 32:10 (the phrase was usually quoted from the Vulgate). King James version: ‘In a desert land, and in the waste howling wilderness’.

† Nemthor or Nemthur, which is probably Dumbarton (one of several possible birthplaces).