FOUR

There’s a record, so you put it on

—“45”

When I was a boy, I liked television adventure programs like Highway Patrol, Whirlybirds, and especially the medieval exploits of William Tell and Robin Hood. The latter’s program was announced by a stirring anthem of hunting horns and a vocalist singing the refrain:

Robin Hood, Robin Hood, riding through the glen

Robin Hood, Robin Hood, with his band of men

Feared by the bad, loved by the good

Robin Hood, Robin Hood, Robin Hood

I met him once. Not Robin Hood, of course, but the man who sang that song. His name was Dick James. I was eight years old and he was chucking my cheek, and I didn’t much care for it. My Dad had taken me with him to an address on Denmark Street, London’s Tin Pan Alley. I don’t know what business he had in a publisher’s office, but my father did write a few songs. Perhaps he was trying to get one of his own compositions placed.

Now this man was pinching my face and making a theatrical show of it. My guess is that he was deflecting the parent by flattering the child.

Every week, my Dad would bring home a stack of sheet music to learn, some of it printed with pictures of the artist on the front, the rest of it beautifully transcribed with an italic pen. Along with the song sheets came advance vinyl copies of the new singles, most of them overprinted with a big A on the label so that you didn’t play the wrong side of the record.

Most urgent of all were the acetate discs that didn’t even come from the record company but were dubbed and dispatched directly by music publishers looking to generate performance royalties on those songs. These discs played just enough times to learn the tunes before they would wear out, like when a secret agent in a spy movie is instructed to his swallow orders after reading them.

One of the curiosities of the British music scene in the early ’60s was the “needletime agreement” that had been struck between the BBC and the Performing Rights societies and the Musicians’ Union. Only five hours of recorded music could be played per day. Everything else had to be performed live by a BBC ensemble or a band hired to play on the radio. It generated work for the musicians but also fed all the songs of the day through a strange filter of orchestras on the BBC Light Programme, the musical frequency that ran adjacent to the Home Service.

You could turn on the wireless in 1961 and believe that it was still 1935. You might hear the strings of Semprini playing light classics, or the polite dance music of Victor Silvester and His Ballroom Orchestra, or even a broadcast of someone playing happy tunes on a cinema organ for an entire hour.

It seemed the BBC would do anything to fill up the broadcast schedule, and it was on the air only from early morning, with the “Shipping Forecast,” to just before midnight, when it closed with some improving thoughts from a vicar.

I’d wait all week for Saturday Club, a two-hour show that featured live appearances by pop groups in between the records. Beat groups, as they were now being called, would turn up on variety shows and have jokes made about their hair by comedians who might have only been five years older than them.

The Joe Loss Orchestra may have seemed square to some ears—one famous beat group member once told me, “We used to call him ‘Dead Loss’”—but they made a better job of playing the hits of the day than some of their contemporaries, due to their ingenious arrangements and having at least one very versatile singer. This was often the only way to hear your favorite songs, if not the original artists.

I’d never paid attention to what became of all the records my Dad brought home, until January 1963, when he was asked to learn “Please Please Me” by The Beatles. My folks had registered the novelty of a group of local lads with a funny name when “Love Me Do” had entered the charts, but everything about this record was more startling.

I was used to my father’s voice coming from the front room when he was practicing new songs. It rattled the pane of frosted glass in the door to the hallway.

From my room, I heard my Dad playing this record over and over again, memorizing the descending cadence of the melody, which was made all the more startling by the vocal harmony line in which Paul McCartney seemed to be singing the same note again and again against John Lennon’s lead vocal. When it got to the call-and-response section, I knew that my Dad’s colleagues, Rose and Larry, would be answering his “C’mon” and probably find the whole thing a bit daft, but I couldn’t hear enough of that crescendo, especially when it broke into the title line, with a little falsetto jump on the first “Please.”

I didn’t know any of these words to describe the music back then, but to say that it was thrilling and confusing doesn’t do it justice. I went into the living room and sat quietly on the couch.

My Dad usually didn’t like to be disturbed when he was working, but I suppose he could see that my interest in this song was a little stronger than anything I’d registered before. He bent over the Decca Deccalian record player and fiddled with an arrangement of rubber bands that he’d added to the spindle to trick the arm into landing repeatedly on the groove at the top of the disc while he was working.

“Please Please Me” spun again, and my Dad read down the song copy for the last time, singing along sotto voce. After the record ended, he lifted it off the turntable, put it back in the paper Parlophone sleeve, and dropped it on a pile of sheet music that he’d already memorized. He picked up the next record he had to learn, and started to work on a melodramatic song by actor John Leyton. It was called “The Folk Singer.”

I don’t know how I formed the words exactly, but I asked if he needed “Please Please Me” anymore.

He laughed and handed the record to me.

I don’t know what became of all the records that had passed through his hands prior to this moment. I know a few favorites went onto the family shelf. Perhaps the others were given to friends or even to the women who I now know he was seeing on the side. From that moment on, though, I had the pick of the new releases my Dad was obliged to learn. Those records were going nowhere. I suddenly had ten times the records that my pocket money would have bought me.

As The Beatles’ success grew and grew during 1963, I waited for each new single with the increasing certainty that my Dad would bring it home to learn it and that it would eventually become mine. “From Me to You” arrived next on a white Parlophone label with a big orange A printed on it.

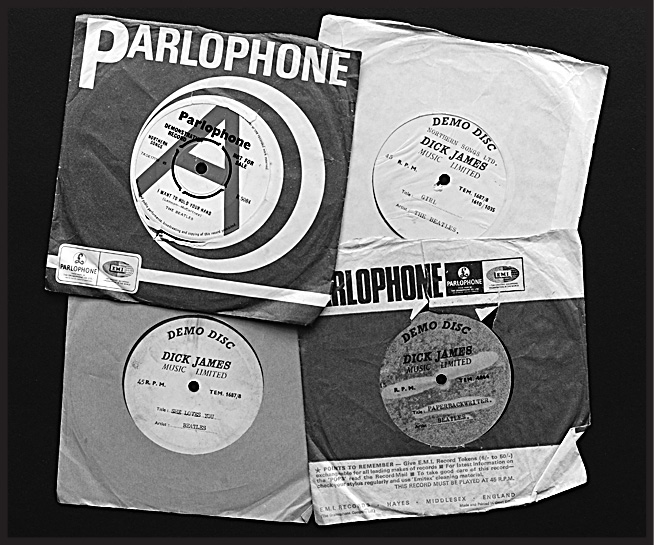

Many of the songs that my Dad was given to learn were so hot off the presses that they arrived on an acetate dub that came with a label reading DEMO DISC and DICK JAMES MUSIC LIMITED printed in bold red type.

In the case of one particular record, someone had typed in the words Northern Songs in a slanted line of black ink. In the space left after the word “Artist,” someone had simply typed “Beatles,” but then had taken the time to type “45” next to a printed “R.P.M.,” before presumably gluing the label to the disc.

The song was “She Loves You.”

Even though these songs were already on the radio, the presence of the records in the house felt special, as if the copies had come from The Beatles themselves, along some inside track.

• • •

ABOUT THREE WEEKS BEFORE the release of “I Want to Hold Your Hand”—another orange A label—The Beatles appeared at the Royal Command Performance. It was then the biggest variety show of the year and starred popular singers, comedians, dancers, novelty acts, and stars of the stage and screen, all for the amusement of the Queen or one of her royal family, and broadcast to her subjects at home with some pomp by Associated Television.

The TV Times went so far as to print a double-page insert, mocked up to look like a formal program with a serrated edge, printed in a typeface chosen to resemble handwritten calligraphy. Everything about it was designed to make the viewer at home feel as if they were sharing an evening at the theater with the Queen Mother and her rather racy daughter, Princess Margaret.

On this occasion, the show featured Max Bygraves, the slapstick comedian Charlie Drake, the South American folk group Los Paraguayos, the North American singer Buddy Greco, and the young English singing star Susan Maughan, who had just enjoyed a hit with “Bobby’s Girl.” Nadia Nerina led a corps of dancers from the Royal Ballet in an excerpt from The Sleeping Beauty, and there were to be sketches from the comedy show Steptoe and Son, though, sadly, not at the same time. Michael Flanders and Donald Swann, who resembled an admiral and a vicar, respectively, would be expected to sing their collegiate favorites—“The Hippopotamus Song” or “The Gnu Song”—while the casts of the musicals Half a Sixpence and Pickwick were to be led in excerpts from the hit West End shows starring Tommy Steele and Harry Secombe.

There was usually a special cameo by a big Hollywood star who might just walk on, wave, and take the ovation, but this year it was a musical performance by Marlene Dietrich, accompanied by her musical director, Burt Bacharach.

Somewhere in the middle of the order came the Joe Loss Orchestra, featuring the vocalists Rose Brennan, Larry Gretton, and Ross MacManus.

Needless to say, the idea that my Dad would be sharing the bill with The Beatles was a lot more exciting than the fact that he was to perform for royalty.

That show is now mostly remembered because John Lennon introduced “Twist and Shout” by saying:

“For our last number, I’d like to ask your help. Would the people in the cheaper seats clap your hands. And the rest of you, if you’ll just rattle your jewelry.”

It was this quip that grabbed all the headlines the next day. There was no mention that my Dad had sung “If I Had a Hammer” for the Queen Mother, who was very fond of work songs, never having had a job of her own.

My memory is that my mother and I watched the show as it happened, but the history books tell me that it had been recorded for later broadcast. Either way, this was long before home video recorders, and such shows were never re-aired, so it might as well have been live, for if you looked away, you missed it. I had to memorize every second of my Dad’s performance as it happened.

Early in 1964, the Joe Loss Orchestra starred in a short cinema release called The Mood Man, in which my Dad reprised the number that he had sung by Royal Command. My mother and I went to see it as a second feature at the local Odeon.

The television appearance had been broadcast in 405 lines of fuzzy black-and-white, but this was in vivid Technicolor. Unlike the Royal Command Performance, it was lip-synched, but what it lacked in musical veracity it more than compensated for with energy and surrealism.

The number opens with a tight shot of hands playing a pair of conga drums and pulls back to reveal a man I recognize to be baritone saxophonist Bill Brown, who I had not previously associated with the playing of Latin percussion. Ross’s feature was the reprise of “If I Had a Hammer,” arranged after the Trini Lopez version, featuring only a rhythm section and massed percussion.

The filmmakers had to do something with the rest of the band, so the members were arranged around a set, playing various bongos, maracas, guiros, and shakers rather than their usual trumpets, trombones, and saxophones. Three hapless souls revolved on a small circular yellow podium for the duration of the entire number, although the camera failed to register what must have been the eventual green of their complexion.

My Dad was dressed in the same off-white suit that he’d worn at the Prince of Wales Theatre and under which he’d been obliged to wear long underwear after the television director claimed that his flesh could be detected through the thin material once my Dad stepped under the television lights, which would be bound to scandalize the royal party.

In the movie, he lip-synchs the hell out of the number, miming “hammer of justice” for all he is worth, while the drummer, Kenny Hollick, beats time on a gold-sparkled drum kit. The close-ups that come on the repeated line “It’s a song about love between my brothers and my sisters” are eerie to behold for the similarity of our facial expression at about this age and especially when singing particular words.

Where my Dad holds the advantage over me is in his dance moves.

Those are steps that I am yet to master.

It is a terrific curio of a lost time and a way for me to recapture the thrill of that night in November ’63.

The morning after the Royal show, there was all the excitement of hearing about the backstage scene. Over breakfast, I tried to play it cool.

“Did you meet Steptoe and Son?” I asked casually.

After all, Joe Loss had a novelty number named after the comedy rag-and-bone men.

“And Dickie Valentine?”

Eventually, I couldn’t pretend that I really cared whether he’d stood next to Charlie Drake in the presentation line or had shaken hands with the Queen Mum. I blurted out:

“Did you actually meet The Beatles?”

It had obviously been a long night or an early morning, as my Dad wasn’t that talkative. He mumbled something about them being very nice lads. Then he reached into a jacket slung over the back of his chair and pulled out a sheet of thin airmail paper and handed it to me.

I unfolded it, and there were the signatures of all four of The Beatles on one page. I’d seen reproductions of their signatures in enough magazines and fan club literature to know that these appeared to be the real thing.

The ink seemed barely dry.

What I did next will bring tears to the eyes of those who make a fetish of such objects, but I had only a small autograph book and the paper was too large to be mounted in it.

I carefully, if not so very carefully, cut around each of the signatures, lopping off the e of the “The” in “The Beatles” and pasting the four irregular scraps of paper into my album.

You might say that it was me who broke up The Beatles, and it only took a pair of scissors.