2

A FATHER AND HIS DAUGHTER

Giuseppe Verdi was a rather withdrawn, isolated boy, lost in his own world. We know this because many of his contemporaries were keen to offer their assessment of him once he achieved fame. Consider this description:

[He was] quiet, all closed within himself, sober of face and gesture, a boy who kept apart from happy, loud gangs of companions, preferring to stay near his mother or alone in the house. There lingered about him an air of authority; and even when he was a boy, the other children pointed him out as someone different from the rest of them; and they admired him in a certain way.

This description came from boys who knew him as a schoolmate, offering their opinions many decades later, when the man they had known as a child was universally admired. Their opinions obviously benefited from hindsight. But such a vivid description offers a real insight into the character of this young musical prodigy.

We can clearly picture a boy who kept himself apart, who did not join in with other youths of his age in schoolboy pranks and games. While the others were letting off steam, Giuseppe no doubt preferred to go to San Michele and practise the organ. There was a separateness there, a seriousness that set him apart.

No doubt the boy was joshed by his schoolmates, until they attended Sunday Mass and witnessed for themselves what he was capable of on the organ. Small wonder they ‘admired’ him. One can imagine them giving him something of a wide berth. ‘Different from us,’ they might well have said. Giuseppe must have been aware of this, and so the apartness would have grown still more marked.

We can imagine a shy, reticent boy, at the age of ten – at the time his life was about to change – blessed with an extraordinary talent that marked him out as different but that at the same time confined him to his own world.

If Giuseppe felt any trepidation at being about to leave his family, and the village he had been born in, perhaps he also felt some relief that he could now indulge his ‘differentness’. He knew he was unlike those he had grown up with. Time to spread those musical wings.

The town of Busseto lies just three miles from Le Roncole but it seems a world away, now as it did in Verdi’s time. Situated between the bustling cultural centres of Milan and Parma, it might easily have been squashed into insignificance. But since the Middle Ages it has boasted a tradition of art, music, literature, philosophy and architecture.

When Carlo Verdi decided his son needed to further his education away from Le Roncole, no discussion was necessary as to where that should be. Busseto was the obvious choice. Apart from its tradition of culture and learning, it lies less than an hour’s walk from Le Roncole.

Shortly before Giuseppe left Le Roncole, his early teacher and benefactor Baistrocchi had died. Giuseppe was his natural successor as organist at San Michele. This necessitated playing at Sunday Mass, and he would be able to make the journey home to Le Roncole easily each weekend without the cost of transport.

Later in life Verdi would complain about this. Pleased though he may have been to get away from the confines of Le Roncole, he nevertheless was having to study away from home, lonely enough in itself, but added to this was the fact that when he should have been concentrating on his studies he had to make the arduous trek to Le Roncole every weekend to perform his church duties.

He told an interviewer many years later that on one occasion, on a winter’s day in frost and snow, he fell into a deep ditch, ‘where I would probably have drowned if a peasant woman on the path had not heard my cries and pulled me out’.6 There could well be some truth in this, though I suspect those twinkling eyes might have betrayed a certain embellishment in the telling.

Giuseppe moved into lodgings with a few worldly goods and his beloved spinet. He enrolled in the local school for boys, the ginnasio, and there encountered the first of three men in Busseto who were to have the most profound effect on him.

The school was run by Don Pietro Seletti, who ensured Giuseppe received instruction in Italian grammar, Latin, humanities and rhetoric. Seletti was something of a polymath. He had written academic works on Greek and Hebrew, was a historian and astronomer, ran the well-stocked local library, and would go on to found an academy of Greek language and literature.

But of more relevance is the fact that Don Seletti was an amateur musician who played the viola in the local church orchestra. His initial inclination was to steer Giuseppe towards the priesthood. It was not long, though, before the boy demonstrated where his talent lay, and Seletti had the good judgement to realise the nature of his true vocation.

Through Seletti, Giuseppe was brought to the attention of Ferdinando Provesi, organist at the Church of San Bartolomeo, and director of Busseto’s music school. Provesi was a highly talented musician, a composer of operas, Masses, symphonies, songs and cantatas. Young Giuseppe Verdi could not have fallen more firmly on his feet.

It was not long before Giuseppe was actually teaching his fellow pupils. If there were any lingering doubt as to just how talented the boy was, it was dramatically dispelled when an elderly gentleman engaged to play at a special church service withdrew.

Seletti, clearly confident of the boy’s abilities, asked Giuseppe to take his place. He played with such virtuosity that all those present were stunned. Afterwards Seletti asked Giuseppe whose music he had played. Giuseppe, blushing, replied, ‘My own, Signor Maestro. I just played it as it came to me.’7

It was Giuseppe Verdi’s first public performance in Busseto. He was no more than thirteen years of age.

He also began to compose around this time, and compose prolifically. In a letter written many decades later, he stated that:

From my thirteenth to my eighteenth year … I wrote a wide variety of music, marches by the hundred for the band, perhaps hundreds of little works to be played in church, in the theatre, and in private concerts; many serenades, cantatas (arias, duets, many trios), and several religious compositions, of which I remember only a Stabat Mater.8

Given that few of these ‘hundreds’ of pieces have survived, we can assume a degree of exaggeration on Giuseppe’s part. But the fact remains: in his teenage years he was not only performing music, he was writing it as well.

A year or so after that first public performance, he made his debut as a composer. He wrote an overture for Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia, which was performed by an opera company visiting Busseto. The audience was enraptured. Applause and ovations were ‘long and extremely noisy’.9

Small wonder that before he reached the age of twenty, he was renowned in all quarters of the highly cultured and sophisticated town of Busseto as a young man of quite exceptional musical talent. He was no longer Peppino; he was Verdi the musician, keyboard virtuoso and composer.

Busseto boasted its own Philharmonic Society, in which Provesi was a leading light. Through Provesi, Giuseppe Verdi became involved with the Society. One of the venues in which the Society’s orchestra performed was the salon of a handsome town house owned by one of the leading citizens of Busseto, Antonio Barezzi.

We do not know exactly when and how Verdi met Barezzi, though we can safely assume it was at a musical performance in Barezzi’s house. The relationship he would develop with the older man would alter the course of his life.

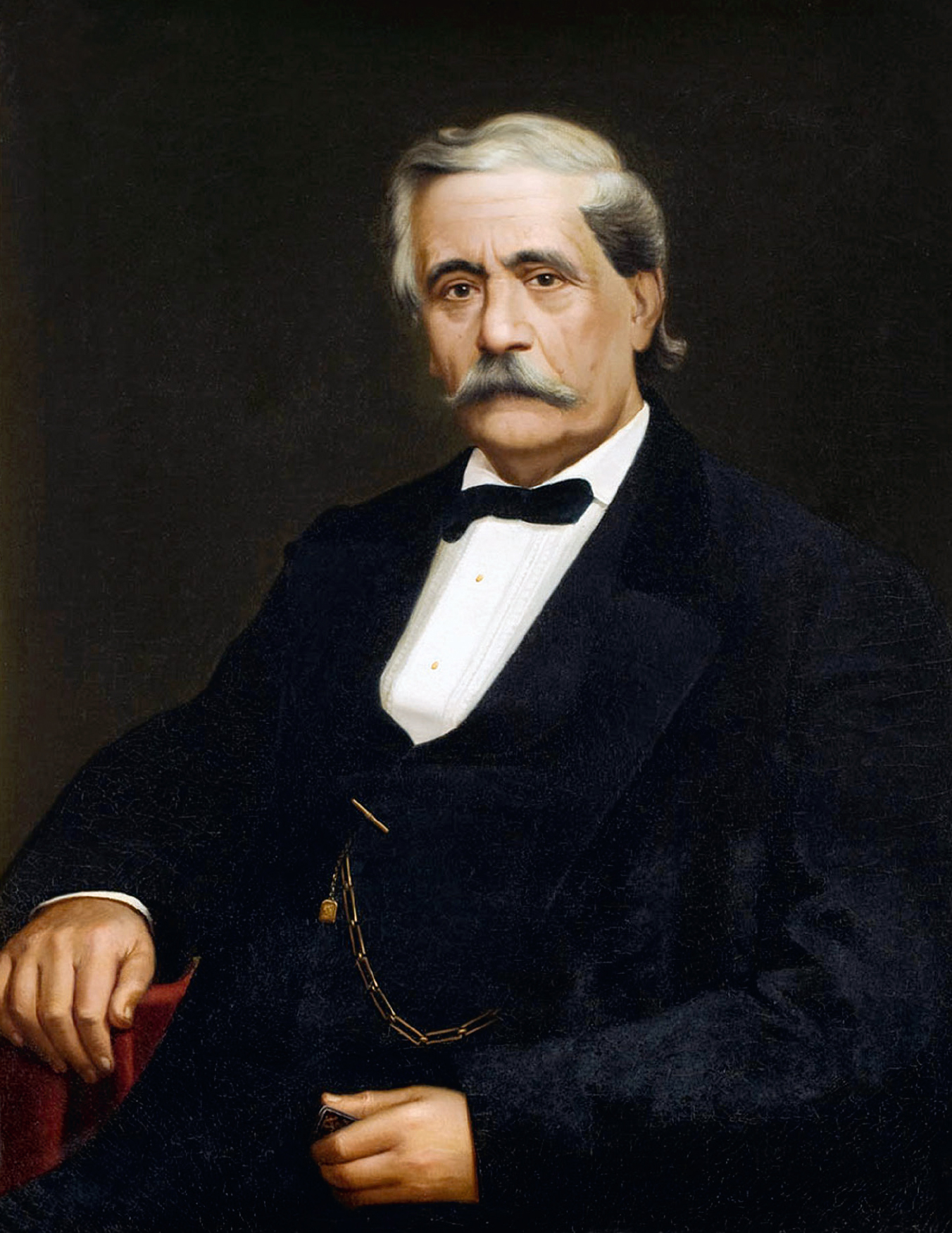

A portrait of Antonio Barezzi painted ten years after his death shows a formally dressed man in old age, wearing a black bow-tie, a starched white dress shirt with studs, a low-cut waistcoat sporting a gold watch chain, and a black evening suit. He has immaculately combed grey hair, parted on the left, an elaborate and perfectly coiffed moustache, heavy eyebrows, dark eyes and a serious unsmiling expression.

Barezzi was a wholesale grocer and distiller, and had grown wealthy on the success of his business. Of the utmost significance to the young Verdi, he was also dedicated to music. He was competent on several instruments, among them the flute, clarinet and ophicleide (a forerunner of the tuba). Demaldè described him as a ‘manic dilettante’ of music.

Barezzi played in the orchestra of the Philharmonic Society, as well as making his salon available for rehearsals and performances. It was inevitable that he would sooner or later meet the young musician who was making such a name for himself in Busseto. Inevitable, too, that Verdi would meet Barezzi’s eldest daughter, Margherita, a fine singer who was seven months younger than him. It was not long before he began to teach her, accompanying her on the piano.

Nor was it long before a mutual attraction developed. His friend Demaldè wrote later that such was Verdi’s shyness in front of other people that no one realised he and Margherita had fallen in love. It would be some time, though, before the romance was allowed to flourish, and a number of setbacks would have to be overcome first.

Verdi’s natural shyness was compounded by a fierce independence of spirit, something that would mark him out throughout his life. In Busseto he was the country boy, the outsider. Beyond his talent for music, there was little about him to attract attention. He moved in a very small circle of boys of his own age, and with the exception of Demaldè, who would be the first to write an (unfinished) biography, his ‘apartness’ prevented any really close friendships from developing.

One quality Verdi most certainly did not lack: confidence in his own musical ability. Perhaps to distance himself from the people of Busseto, perhaps to prove to them his worth, he applied for the post of organist at a church in a small town close to Le Roncole. He was sixteen years of age. He was turned down. It must have been a huge blow to his self-esteem, but it was nothing compared to what lay ahead.

Just a few months later he received the devastating news that his father, who had failed to keep up the rent on the family home and lands in Le Roncole, was to be forcibly evicted with his wife and daughter. Carlo Verdi had overstretched himself, and was already in arrears when he renewed the lease.

His petition to remain, and his promises to clear the debt, fell on deaf ears – the deaf ears of the local bishop to be precise, who prevailed on the court to issue an eviction order. On 11 November 1830 the Verdi family moved out of the house they had lived in for nearly forty years – the probable birthplace of their son – and took up a tenancy in the tavern that today claims that distinction.

At this point Antonio Barezzi became more than just an admirer of the young musician; he became Verdi’s protector and benefactor. He took Giuseppe Verdi into his own house and gave him a room. This marked the beginning of a relationship that both individuals would treasure, Verdi expressing his gratitude to the older man until his dying day.

Barezzi gave Verdi a comfortable and spacious bedroom-cum-sitting room off the landing on the first floor of the house, with a bed at one end, and a sofa, two armchairs and several upright chairs at the other. The window was hung with heavy curtains, and the walls covered with French paper. On the plaster over the door Verdi himself wrote, ‘G. Verdi’.*

I have seen it written that neither Barezzi nor his wife were aware of the mutual attraction that had developed between their daughter and the young musician, but that is surely not credible. It is more likely that not only were they aware of it but that they did little to discourage the two young people. Barezzi, with his passion for music, might even then have been eyeing up Verdi as a potential son-in-law.

For the immediate future, though, Barezzi had other plans. He could see better than most that Verdi, now eighteen years of age, had outgrown Busseto. There was nothing in the town for the young man to aspire to. Barezzi knew that there was only one path for this remarkably talented musician to take. He needed to go to the cultural capital of northern Italy, Milan, and study at the Milan Conservatory.

No doubt encouraged by Barezzi, Verdi’s father applied to a charitable institution in Busseto for a four-year scholarship for his son to study music in Milan. When it seemed as if the application would fail, it was Barezzi’s agreement to subsidise the first year that probably did the trick. Once again Verdi had reason to be grateful to his benefactor. All that lay between Verdi and the conservatory was the entrance exam; with his innate musical talent that would be a formality.

Giuseppe Verdi, approaching his nineteenth birthday, was about to leave the town where he had lived for almost ten years. The big city awaited him. This, surely, was where his extraordinary musical talent would be discovered, encouraged and nurtured; where he could attend opera at La Scala and meet those with influence in the world of music. He would fit into the milieu there with far more ease than he ever had done in Busseto.

But that was not how it was to be. Things were to go wrong for him from the start.

* The room was preserved in its original state well into the 1960s.