6

‘LITTLE BY LITTLE THE OPERA WAS COMPOSED’

What happened next in the life of the young composer is enshrined in legend – several legends, in fact. There are four different accounts of how he came to write the opera that changed his life – all originated from Verdi himself, three of them related at different times and to different friends and colleagues, who then wrote their own version of what he had said. They are all dramatic to a greater or lesser degree; Verdi’s own account, unsurprisingly, is the most dramatic of them all.

His version comes, once again, in conversation with his French biographer Pougin many years after the event. With all the necessary cautions previously expressed – his predilection for exaggeration, a desire to enhance the drama, genuine mistakes of memory, or dubious details so enticing he has come to believe them himself – it is worth giving Verdi’s account at length. It reveals as much about the man as it does the creation of his new opera.

The rerun of Oberto had done little to lift his spirits. Merelli told him that seventeen performances was a good run. Verdi quoted back at him a newspaper review that said the music, especially in the first act, seemed less thrilling this year than it was the year before.

He could not shake the depression that hung over him. He was still contemplating abandoning a musical career altogether. He remained under contract to Merelli but was earning nothing and was continually short of money.

He decided to move out of the apartment he had shared with his wife and son, and rented a single furnished room. He shipped all his furniture back to Busseto. He stayed in the darkened room for most of the day reading cheap novels. He saw practically no one. Verdi was consciously distancing himself from music and its world.

And then, as heavy snowflakes fell one winter evening in 1840, just a couple of months or so after the failure of Il giorno, Verdi was walking through the galleria that ran from La Scala down towards the cathedral, when who should he bump into but the impresario Merelli himself, walking from his home to the theatre.

Merelli took young Verdi by the arm and suggested he come with him to his office at La Scala. Verdi had nothing better to do, so allowed himself to be persuaded. As the two walked along, Merelli bemoaned the fact that he was once again in deep trouble. He had given a new libretto by Solera to the composer Otto Nicolai, who had had the gall to profess himself dissatisfied with it.

‘Imagine,’ said Merelli, ‘a libretto by Solera, stupendous, magnificent! Extraordinary! Effective dramatic situations! Grand beautiful lines! But that crank of a composer refuses even to look at it. He says it is an impossible libretto! I don’t know where to look. I need to find him another one right away.’24

Giuseppe Verdi to the rescue, at least in his own version of what transpired. He reminded Merelli that he had given him a libretto to work on, as the third opera he was under contract to write. It was called Il proscritto. He told Merelli he had not written a note of it. Would he like it back? He could give it to Nicolai.

‘Oh bravo! That is a stroke of good luck!’ Verdi quoted Merelli as saying.

Once in his office, Merelli sent an underling off in search of a second copy of Il proscritto. At the same time he reached into a drawer and out came the libretto by Solera that Nicolai had rejected.

‘See, here is Solera’s libretto! Such a beautiful plot! Imagine turning it down!’ And then, tossing it across the desk to Verdi, the crucial words: ‘Take it. Read it.’

‘What in the devil do you want me to do with it?’ Verdi retorted. ‘No! No! I have no desire to read librettos.’

‘Well, it’s not going to hurt you. Take it home, read it, then bring it back to me.’25

That is Verdi’s account of the single most momentous conversation of his life. It would be unwise to dismiss it. It is Verdi dramatising a meeting that we can be certain took place. And it becomes much more credible if we see it from Merelli’s point of view.

He was genuinely in trouble over the new opera, given Nicolai’s rejection of it. Nicolai was a composer who had had no great success with his operas to date.* Oberto had shown Merelli what Verdi was capable of, and who had been librettist of that? The same Solera whose libretto Nicolai had dismissed. Verdi and Solera had worked well on Oberto. What if Merelli could persuade Verdi to have a look at this new libretto?

Verdi got up to leave and Merelli handed him a huge sheaf of papers, which Verdi rolled up. He left for the short walk home. Is it too fanciful to imagine Merelli punching the air in a small gesture of triumph, or allowing himself a smile of satisfaction that he had persuaded Verdi at least to take a look at Solera’s libretto?

As he walked home through the snow, Verdi described how he felt ‘a kind of indefinable, sick feeling, all over, an immense sadness, an agitation that made my heart swell!’26 This is a prelude to the best-known part of this legendary tale, better known perhaps than any other single moment in the creative process in Verdi’s long and productive life.

I shall let Verdi tell it himself, in words noted down by Pougin:

I went to my place and, with an almost violent gesture, I threw the manuscript on the table, and stood straight in front of it. The bundle of pages, falling on the table, opened by itself. Without knowing why, I stared at the page before me and saw the line ‘Va, pensiero sull’ali dorate’ [‘Fly, thoughts, on golden wings’]. I ran through the lines that followed and got a tremendous impression from them, all the more moving because they were almost a paraphrase of the Bible, which I always loved to read.

I read one section; I read another. Then, firm in my decision not to compose again, I forced myself to close the manuscript and go to bed. But YES! Nabucco was racing through my head! I could not sleep. I got up and read the libretto, not once, not twice, but three times, so that in the morning, you might say, I knew Solera’s whole libretto from memory.27

Credible? That he tossed the rolled-up pages onto the table and they fell open at the words that would become the most famous lines of music he would write in his entire career? A sleepless night, at the end of which he could recite practically the whole libretto?

In fact Verdi himself unwittingly casts doubt on his own version by telling a rather different story to another friend. According to that version, when he got home with the rolled-up libretto, he threw it in a corner, where it stayed untouched for a full five months, while he spent his time devouring trashy novels.

Only then did he begrudgingly pick it up, go to the piano, and set the scene in which the main female character dies. But it was enough:

The ice was broken. Like a man emerging from a dark, dank jail to breathe the pure country air, Verdi again found himself in the atmosphere he adored. Three months from then, Nabucco was finished, composed, and exactly as it is today.28

Well, not entirely. That scene was later dropped, and Verdi would be making changes right up to the first performance, and after.

But a legend is a legend, and no legend exists without some truth at the base of it. The story of the pages falling open at what became ‘The Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves’ has most certainly stuck. Go to any performance of Nabucco in any opera house in the world, and you will surely read it in the programme.

In fact Verdi’s own account, as told to Pougin, does not end there. After the almost certainly inflated claim that by morning he knew Solera’s whole libretto from memory, Verdi said he was still resolved not to compose again, and the next day duly returned to La Scala and gave the manuscript back to Merelli.

But Merelli was not taking no for an answer.

‘Beautiful, eh?’ [Merelli] said to me.

‘Very. Very beautiful.’

‘All right, then, set it to music!’

‘Not a chance! I would not even dream of it. I don’t want anything to do with it.’

‘Set it to music! Set it to music!’

And, saying this, Merelli took the libretto, stuck it in the pocket of my overcoat, took me by the shoulders, and, with a big shove, rushed me out of his office. – Not just that; he closed the door in my face and locked it!

What was I to do?

I went back home with Nabucco in my pocket. One day, one line; one day, another; now one note, then a phrase … little by little the opera was composed.29

It is a beguiling account. The reluctant young composer, the former composer, resolved to compose no more, being forcibly talked into it by Europe’s most powerful theatrical impresario. Perhaps he did protest too much. Perhaps he protested only a little.

It does not matter. The final sentences are without doubt entirely true. It was a slow process, but little by little Verdi composed his Nabucco.

It is at this point that Giuseppina Strepponi re-enters Verdi’s life. She had been away from Milan for some time. Whether this was as a direct result of the latest development in her life is not clear. She was pregnant again, for the third or possibly fourth time, and as with her previous pregnancies it was not entirely clear by whom.

Nor is it clear whether Verdi was aware of this. What is certain is that he wrote the part of the main female protagonist, Abigaille, with Giuseppina in mind. He wanted her in his opera, and he made this clear to Merelli. Merelli did not refuse him. La Strepponcina, even if her voice was not what it once was, remained box-office gold.

The opening night of Nabucco was scheduled for 9 March 1842. Just four months before this Giuseppina gave birth to a girl, who was baptised Adelina Rosa Maria Theresia Carolina. As with her previous children, Giuseppina gave her baby away, this time to a married couple who she paid to take the child, and she had no further contact with her. There is no evidence of how she reacted – if indeed she knew – when Adelina died of dysentery eleven months later.

Despite the fact that Giuseppina’s voice had deteriorated significantly, Verdi was still determined she would sing the role of Abigaille. Before each full rehearsal, he rehearsed her separately at the piano. He had written an enormously complex part, with some death-defying leaps of two octaves in one of the arias.

Given what was at stake – a brand new opera by a young composer whose last effort had resulted in a fiasco, being staged at La Scala in front of the most discerning audience in Italy – it is hardly surprising that there was plenty of tension in the air.

Things did not go entirely smoothly even between Verdi and his librettist, though he was able to make light of it when recounting it years later to Pougin.

Solera had written a love duet in Act Three, which Verdi thought slowed the pace of the action too much. Instead he wanted the High Priest Zaccaria to prophesy that God would destroy Babylon. ‘Here,’ said Verdi, handing Solera a Bible, ‘you already have the words. They are in here.’

The two men argued, then Verdi – as he recounted it – locked the door of his apartment, put the key in his pocket, and told Solera he was not leaving until he had written it. There was an ‘ugly’ moment, said Verdi, as he saw ‘a fire of rage’ burning in Solera’s eyes, ‘for the poet was a large man who could quickly have done away with that obstinate composer’.

But all ended well. ‘After a moment [Solera] sat down at the writing table, and fifteen minutes later the Prophecy was written.’30 To this day Zaccaria’s Prophecy, following ‘The Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves’, remains one of the most dramatic passages in the entire opera.

Only twelve days were available for rehearsals before opening night on 9 March – far too few for such a complex production. As rehearsals progressed, problems multiplied without being solved.

The biggest concern was Giuseppina’s voice. Verdi was by this point genuinely worried that it was in such a poor state that the whole opera might have to be postponed; it was too late for another singer to step in. Rumours began to fly. Verdi had not wanted her to sing in the first place, but Merelli insisted; Merelli had not wanted her to sing in the first place, but Verdi insisted. Blame for inevitable failure was already being apportioned, even before the opening night.

There was confusion over the entrance of the onstage band. Verdi seemed unable to convince its leader of the right cue. Costumes had been rather haphazardly made and were hardly likely to impress the audience. The stage scenery had been borrowed from a ballet production and hurriedly repainted.

Verdi himself was making changes right up to the dress rehearsal, and at the very last minute – after the dress rehearsal and before the first performance – composed an overture. One can imagine the orchestral players’ consternation. For those of a superstitious disposition, perhaps the most worrying omen was that the dress rehearsal went superbly. Everything came together. Giuseppina proved she could still sing; even the band entered on cue. At the final curtain, stagehands roared their approval and beat the floor with their tools.

Everything was in place for a disastrous opening night. Verdi took his customary place in the orchestra, between cellos and harpsichord. He reported later that one of the cellists, anticipating success, leaned forward to him and said, ‘Maestrino, I wish I were in your place this evening.’

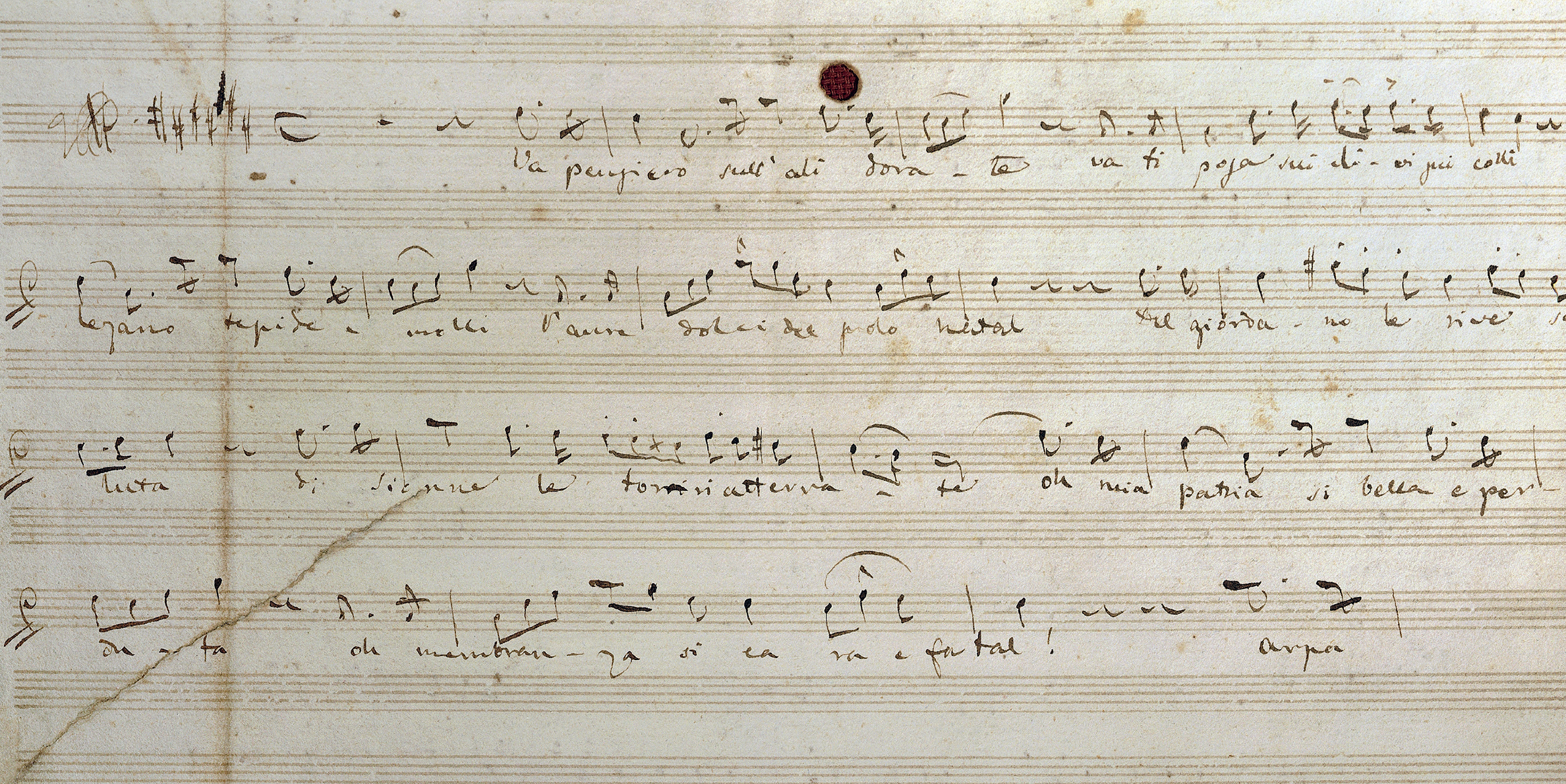

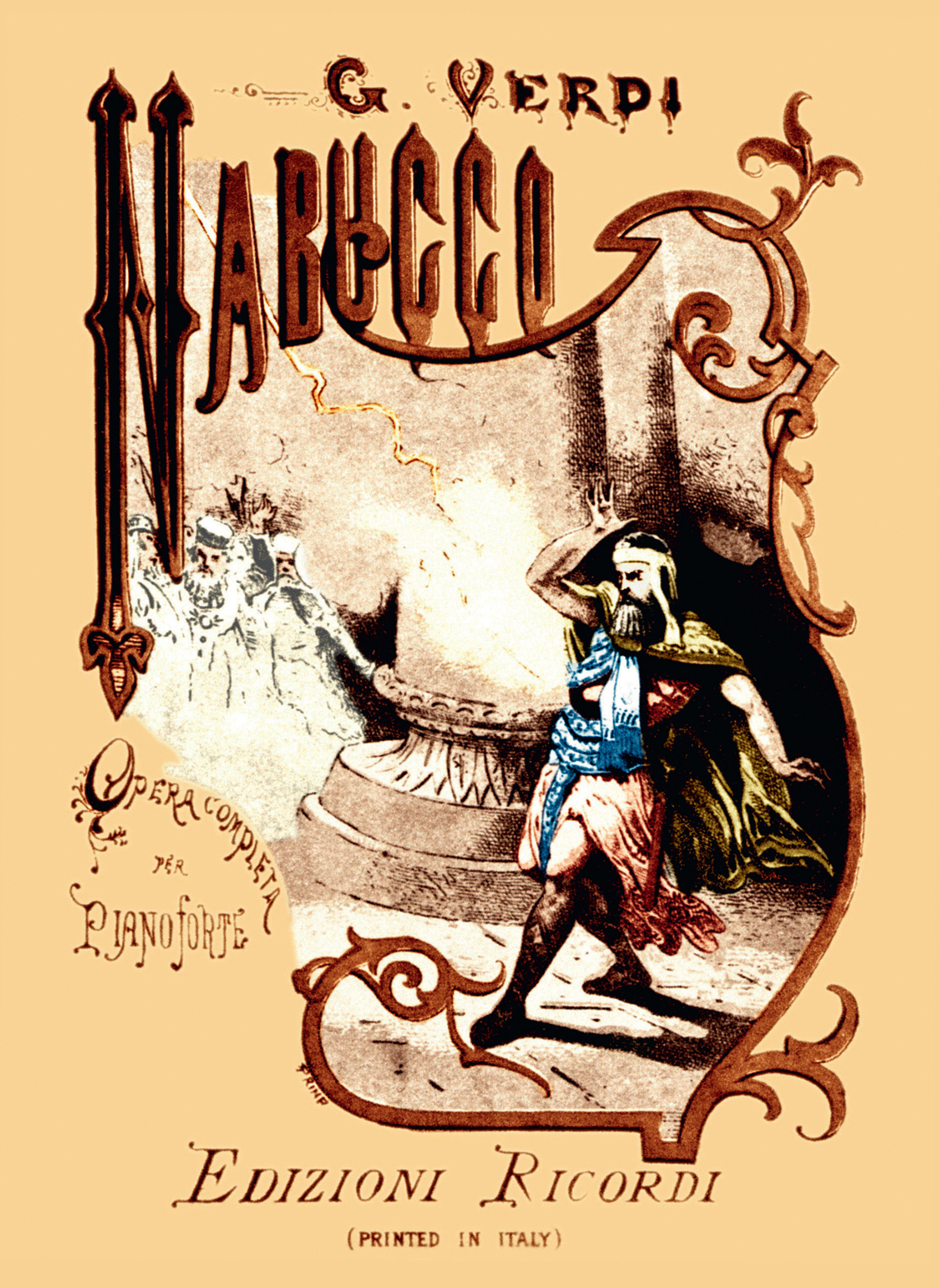

We have only Verdi’s account of the first performance of Nabucco, as told to his publisher and friend Tito Ricordi many years later, quoted in Pougin. If there is any element of exaggeration in it, he can surely be forgiven.

The overture began with portentous chords, followed by a clashing of cymbals and runs on the strings, then the chords again, before a hushed passage full of tension, punctuated by fortissimo chords. Verdi then quotes ‘The Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves’, before any other tune from the opera. He knows what he has created. This was music on an altogether different level – not just from anything Verdi had composed but from anything that had ever been heard at La Scala. And he had written the overture in an hour or so on the day of the first performance.

There was furious applause even as the curtain went up. It barely stopped. Each dramatic moment was greeted with applause and cheers. We have to smile as Verdi told Ricordi he was so nervous that when everyone stood up, shouting and screaming, at the end of Act One, he thought they were protesting: ‘At first, I believed that they were making fun of the poor composer, and that they were about to jump on me and do me harm.’31

I wonder if he genuinely thought that. I can see those twinkling eyes and turned-up lips as he played the poor put-upon composer.

The reviews were unanimous: ‘noisy and enormously well received’; ‘the universal agreement of the audience was beyond dispute’; ‘a surprising effect that moves listeners and causes them to applaud and shout with enthusiasm’.32

Several critics reported that Verdi and the singers were called out onto the stage again and again. Verdi, sometimes alone, sometimes with singers, received ‘loud, endless applause offered by an ecstatic audience’.

There was relief all round that Giuseppina’s voice had held up to the end; the other singers rose to the occasion, and the orchestra was on top form. It was the success that had so far eluded Verdi, that had been so long in coming. From fiasco to triumph in a single night.

After the premiere Verdi walked home with the one man who had stood by him through thick and thin, professionally and in the darkest hours of his young life. Antonio Barezzi had been in the audience at La Scala when Verdi was booed off stage for Un giorno. He was there too for the triumph of Nabucco.

As they walked, Verdi confessed to his father-in-law he had not expected such a triumph, even though the dress rehearsal had shown him how good it could be. Barezzi must have smiled quietly to himself, his early judgement of Verdi’s musical prowess thoroughly vindicated. It is conjecture, but surely Ghita’s name must have passed the men’s lips, and how she would have relished her husband’s success.

Overnight Verdi was the toast of Milan. As Italian opera aficionados do, when they accept one of their own, they applauded and celebrated every aspect of the man:

The night [after the premiere] no one in Milan slept; the next day the masterpiece was the sole topic of conversation. Everyone was talking about Verdi; and even fashion and cuisine borrowed his name, making hats alla Verdi, shawls alla Verdi, and sauces alla Verdi. From every city in Italy impresarios hurried to beg the new maestro to write something just for them, and made him the biggest possible offers.33

Nabucco ran for the scheduled eight performances, and then a further fifty-seven between August and September. That was a record for La Scala, unmatched by either Donizetti or Rossini.

Verdi was finally able to put his in-built scepticism, his natural cynicism, behind him. He told Ricordi years later he knew that night that his career as operatic composer was assured:

With this opera you can truly say that my artistic career began. And although I had to fight against many obstacles, it is certain all the same that Nabucco was born under a lucky star, so lucky that even all the things that could have gone wrong [did not do so, but] helped to make it a success.34

Verdi the operatic composer was on his way, but what of Verdi the man? Nabucco, and indeed what came before, changed Verdi both professionally and personally. Giuseppina gives a fascinating insight into the sort of man the young composer was now.

During those fraught rehearsals leading up to opening night, with Giuseppina struggling to master the role of Abigaille, she described Verdi as cold, deeply mistrustful of men and God, a man who seemed to have turned into stone.

That is understandable, given the tension he was under. But it is also easy to see how his experiences, at home and at work, had changed him for ever. He had lost his wife and two infant children; he had composed two operas, one achieving a modicum of success, the other an outright disaster. He felt he had been manipulated by the musical world – impresarios and singers – ignored by God, used by anyone who thought he could be useful to them.

That had now changed. This was a new Verdi. This was a Verdi who knew his own mind, who knew what he wanted. From now on nothing would stand between him and his aims. That would be the hallmark of the man Giuseppe Verdi had become.

* His best-known opera, Die lustigen Weiber von Windsor (‘The Merry Wives of Windsor’), was still some years off.