12

VERDI SETS TONGUES WAGGING

Verdi was not fond of big cities. He expressed dislike for both London and Paris, and tolerated Milan only because he had no choice. The most famous composer in Italy, internationally renowned, still hankered for a rural life. In mid-1848, between those two most recent operas, neither of which did much to enhance his career, he decided to do something about it.

In April, he returned home for a short visit. It had been a while since he had been to Le Roncole to see his parents; he also caught up with his father-in-law Antonio Barezzi and close friends such as Demaldè in Busseto.

But that was not the prime motive for his return to that small corner of the Po valley, the land where he had grown up and where he always felt most at home. By this point Verdi had earned a substantial amount of money. Financial problems from his property purchases were in the past. It has been suggested that he could have retired completely at this point in his life, had he wanted to do so. Given how many times he had hinted at this in letters to friends, along with withering comments about his profession, it is perhaps surprising he did not do so. (We can at least be grateful for that.)

It was now that he made a major decision about how to spend the surplus money he had accrued. First, he sold the property he had earlier acquired at Il Pulgaro. On 8 May 1848 he signed the deeds on a substantial property, the Villa Sant’Agata. It comprised a farmhouse, outbuildings and several acres of arable land.

It might well have been Verdi’s intention at some point soon to realise – finally – his dream of giving up music and becoming a farmer. At the very least it would provide him with a retreat from the world for which he had developed such distaste. It was secluded, private, and he must have known – even if only subconsciously – that to have a home like that as his base could only nurture and encourage his creativity.

Sant’Agata could not have been better situated, for a number of reasons. Its north-east corner bordered the mighty Po river, whose waters irrigated the soil. Its south-eastern corner touched the smaller Ongina river, its south-western corner the Arda river. With such natural irrigation, the soil was wonderfully fertile.

The estate was just a stone’s throw from Le Roncole, and even closer to Busseto. Its location had one other aspect that appealed to Verdi. The Ongina river, which runs roughly north–south, formed the border between Piacenza province to the west and Parma province to the east.

It soon became local legend that the deciding factor in Verdi’s decision to purchase the estate was the fact that it lay on the western bank of the Ongina, thus falling within Piacenza province. Verdi, it will be recalled, had long since fallen out with the Teatro Regio di Parma (see page 30). Why would he therefore want to live within Parma province? Verdi was a man who did not forgive a slight.

The main farmhouse at Sant’Agata needed substantial work, and from the time he bought the property Verdi began renovations. He would continue them for the best part of the half-century that he lived there.

A year after completing his purchase, Verdi moved his parents into the Villa Sant’Agata, and began making preparations to return to Busseto. He now owned two substantial properties – the Palazzo Cavalli in the centre of Busseto, and the Villa Sant’Agata just a short distance away in the heart of the countryside.

There was no need any more for Verdi to rent apartments in Paris or Milan, or anywhere else he happened to be working. It was a miserable existence, in any case, having to live in towns or cities he disliked. From now on, he decided, people could come to him, rather than the other way round. And he could now choose whether to live in the town or the countryside.

There was another reason for the return to Busseto. He had decided to make a very substantial change in the way he lived. He knew it would not be totally straightforward, that there would be bumps along the way. But even he could not have imagined just how difficult life would become.

In the intervening year between purchasing Sant’Agata and returning to Busseto, Verdi had lived with Giuseppina in Paris as man and wife. It was a state of affairs he wanted to continue. In Paris it had been the perfectly natural thing to do, arousing no comment at all. That was how Verdi wanted it to be in Busseto.

Verdi decided to make the move first on his own, left Paris and Giuseppina, and moved into the Palazzo Cavalli on 29 July 1849. It is easy to imagine the excitement in the town at the return of its most famous son. For twenty years, the talk in cafés, on the street, in salons, had been of how the boy who had played on the organ at Sunday service had gone on to conquer the world of opera, feted in the great opera houses of Europe.

The excitement, however, was not mutual. In those intervening twenty years Verdi had become a stranger to the Bussetans. They might have thought they knew him, but he was no longer the ambitious young man, inexperienced in worldly affairs. Now, with his return, they wanted to rekindle the intimacy, but he did not.

What Verdi wanted was peace and quiet, as he confided in a letter to his publisher; to be left alone to get on with his life. That might be as a composer of more operas, or it might be as a landowner and farmer at Sant’Agata. Either way, his plans did not include an involvement in local affairs.

It has to be said that if Verdi hankered after the quiet life, he did not necessarily go about achieving it in the right way. It was soon local gossip that within days of arriving back in Busseto, he had taken a carriage ride to a villa just outside Busseto, which was the summer residence of a certain baroness he was rumoured to have had an affair with many years earlier. He arrived, the wagging tongues said, to find her ensconced with her lover. It was Barezzi himself, closer than anyone to Verdi, who apparently told his friends Verdi was shocked and disappointed and the relationship was definitively over.

We find the same ambivalence in his relationship to the woman he had decided to share his life with. There was no doubting his intention to bring Giuseppina to Busseto – with all the risks that that entailed – yet, judging by the letters that passed between them, he was hardly playing the part of the ardent suitor.

Giuseppina was in Florence, where she was making financial arrangements for the education of her illegitimate son Camillo.* From there she intended to go to Parma, and from there to Busseto to join Verdi.

Verdi wrote to her in Florence, and as well as habitual moans about most things, he had clearly suggested in his letter that it would be best if he sent someone to meet her in Parma and escort her to Busseto. She replies with horror – mock, maybe, but she is clearly upset that he does not say he will come personally to Parma to meet her.

You tell me about the ugly countryside, the bad service, and on top of that you tell me: ‘If you don’t like it, I’ll have you accompanied (N.B. I’ll have you accompanied!) wherever you like.’ But what the devil! Do people forget how to love in Busseto, and to write with a little bit of affection?’56

Just in case he hasn’t got the message, she adds an unambiguous P.S.: ‘Don’t send anybody else, but come yourself to fetch me from Parma, for I should be very embarrassed to be presented at your house by anyone other than yourself.’ Endearingly, and clearly in jest, she calls him an ‘ugly, wretched monster!’

In that single additional sentence, Giuseppina articulates the fears the two of them must have discussed in Paris, when Verdi made it clear he wanted her to live with him in Busseto.

It is worth pausing for a moment to see this state of affairs through Giuseppina’s eyes. That letter was written days before her thirty-fourth birthday. In probably lengthy, possibly fraught, conversations with Verdi in Paris, she had agreed to come to Busseto to live with him.

In so doing, she was effectively giving up the life she had worked so hard to build up. She was leaving Paris, which she had made her home, where she had established a career for herself as a singing teacher, having accepted her life on the operatic stage was over, where she had friends and an active social life. She was, in her biographer’s words, ‘burning her only bridge’.57

What was she leaving all this for? As that single sentence in her letter shows, it was an uncertain future. She was – and she knew this would be general knowledge in Busseto – Verdi’s mistress, and also the mother of several illegitimate children. As well as this, she had, in effect, replaced a much-loved young woman, a Bussetan born and bred, daughter of one of the town’s most prominent and respected citizens, who had died tragically young, along with the two children she had borne Verdi.

Verdi himself must have reassured her in Paris that he would be able to control events. With his reputation, with his fame, he would make sure her life was a good one, accepted by everyone as the woman who shared his life. She, clearly, still had her doubts.

Verdi at least did the noble thing and went to Parma to fetch his Peppina. In an open carriage, on 14 September 1849, the two of them rode into the main street of Busseto, the Via Roma.

The Via Roma (then, as now) is a colonnaded street, its elegant arcades separated by decorated pillars. Were there many pairs of eyes blinking behind shutters, straining for a first glimpse of the woman their most famous son had brought home?

Palazzo Cavalli was built round an internal courtyard, its frontage overlooking the Via Roma. The couple was thus able to enter the building unseen, but the windows of the main rooms on the first floor gave out over the Via Roma. One can imagine Verdi fastening the shutters as soon as he and Giuseppina entered their new home.

If the people of Busseto were looking forward to involving Verdi in local life, they were soon to be disappointed. He deliberately sought out solitude, as he made clear in a letter to Piave:

We eat here, we sleep, we work. I have two young horses to take us for a drive – and that is all. The life that I lead is an extremely solitary one. I do not visit anyone’s house, and I receive no one excepting my father-in-law and my brother-in-law.† You, however, can do whatever you want!!! You can go to the café, to the bar, wherever the devil you like.

If Verdi seemed envious of the lifestyle Piave was able to enjoy, he had it in his power to correct matters. Invitations poured in for Verdi from the moment of his arrival back in Busseto – for him, at least, not Giuseppina. He turned them all down.

In another letter, written slightly later, he wrote:

I have lived all this time [since leaving Paris] in a country place, far from every human contact, without news, without reading any newspapers, etc. It is a life that turns men into animals, but at least it is quiet.

One is tempted to say he had only himself to blame. This was the life he had chosen for himself and his Peppina.

For some days, maybe even for the first few weeks, Giuseppina stayed cloistered in the Palazzo Cavalli. When, finally, she ventured out, she found herself ignored by the locals. Her greetings went unanswered. She was left in no doubt that she was unwelcome.

In the evening, with alcohol flowing in the cafés and bars of the Via Roma, insults were shouted beneath the Palazzo Cavalli. It is a local legend, repeated to this day, that on one or more occasions, stones were thrown up at the first-floor windows.‡

It was a difficult state of affairs, made worse by the loyalty of even such a friend and admirer of Verdi as his father-in-law being sorely tested. To have seen and met Giuseppina in Paris was one thing. Here, in his home town, it was entirely different.

Worst of all for Verdi, his own parents left him in no doubt that they thoroughly disapproved of his living arrangements. His mother had even had a bed moved from the Palazzo Cavalli to Sant’Agata in the hope that her son would abandon his mistress and come and live with his parents in the country.

It was the beginning of a period of tension between Verdi and his parents, which would worsen as time passed.

Meanwhile, there was work to be done. Verdi, to his chagrin and despite all his earlier intentions to give up composition, had an opera to write. In the event it would involve almost as much drama offstage as on.

The opera house at Naples, the Teatro San Carlo, reminded Verdi he was under contract to write an opera for them, which had been delayed due to the upheavals of the 1848 uprisings. The librettist they had contracted was the same Salvatore Cammarano with whom Verdi had worked on La battaglia di Legnano, the official librettist at the Teatro San Carlo.

Verdi had previously found Cammarano congenial to work with, and had approved of the libretto he had provided. But the librettist was now in something of a state. Knowing Verdi was reluctant to fulfil his obligation, Cammarano wrote pleadingly to him.

The opera house had informed him that if the opera was not ready to stage by the end of the year 1849, they would slap a fine on him. If he was unable to pay it, they would put him in prison. With a wife and six children to support, he wrote to Verdi, begging him to agree to write the opera.

Verdi acquiesced, but with ill grace: ‘I will write the opera for Naples next year for your sake alone. It will rob me of two hours peace every day and of my health.’58

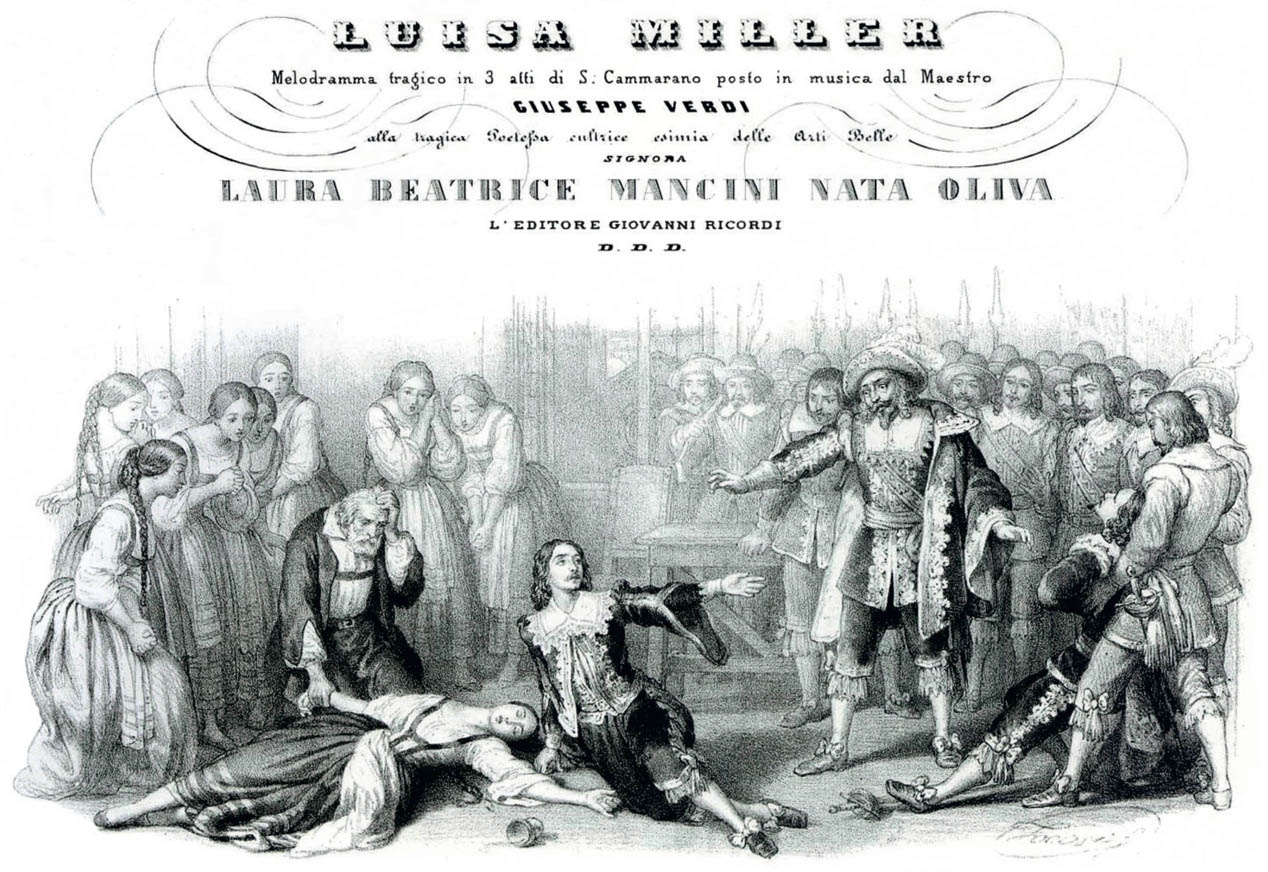

After initial problems with the censor, Verdi and Cammarano agreed they would adapt a Schiller play, stripping it of all political overtones, and concentrating on domesticity and relationships. They retitled it Luisa Miller.

Verdi took a keen interest – as he always did – in the writing of the libretto, making a raft of suggestions to Cammarano, but clearly evident in his correspondence is a respect for the librettist, which he was no doubt pleased to see was reciprocated.

Cammarano wrote to him: ‘[It is] my firm opinion that when [an opera] has two authors they must at least be like brothers, and that if Poetry should not be the servant of Music, still less should it tyrannise over her.’59 Verdi probably could not have put it better himself.

If Cammarano had at least avoided a fine and possible imprisonment, things were not looking good in any other respect. Verdi arrived in Naples to supervise rehearsals to find a letter from Cammarano warning him that the Teatro San Carlo was in serious financial trouble. Cammarano advised Verdi that as yet he had received no payment, and that Verdi would do well to demand the advance due to him – one third of his fee – as soon as he set foot in Naples.

This the composer did. The theatre refused to pay. Verdi countered by threatening to suspend rehearsals. The theatre went on the attack. If Verdi did that, they would invoke a law whereby he would be detained and prevented from leaving the city. Verdi escalated the dispute by saying that, in that case, he would seek asylum aboard a French warship anchored in the Bay of Naples, and take his score with him.

Perhaps both sides realised the absurdity of the level to which matters had escalated. The theatre assured Verdi he would be paid in full, if not entirely on the date due, and Verdi allowed himself to be mollified.

There was the usual trouble with singers, but Luisa Miller opened on schedule just before the turn of the year, on 8 December 1849. It was well received, and productions of it were staged over the next two years in Venice, Florence and Milan. It was seen in Philadelphia in 1852 and London in 1858.

Verdi was pleased to be done with Naples. As he returned home he caught a heavy cold, perhaps the final unwelcome gift from a city he had no desire to see ever again.

Verdi had now fallen out with the managements of three of Italy’s major opera houses – La Scala in Milan, the Teatro Regio di Parma and the Teatro San Carlo in Naples. For a lesser operatic composer this would have been fatal. But Verdi knew these opera houses needed him more than he needed them, and he would make them pay for their intransigence.

Neither Parma nor Naples would ever see the premiere of another Verdi opera, and Milan would have to wait another thirty-five years before it did so.

It was, once again, a changed Giuseppe Verdi who returned to Busseto after just three performances of Luisa Miller. The euphoria of 1848 had dissipated. The cities liberated from the Austrians had all been retaken and reoccupied. An independent Italy remained a dream. Verdi was disillusioned with politics. Not for him any longer heady discussions and arguments in salons of the nobility.

In a sense Verdi was withdrawing into himself. It would not last for ever; before too long he would re-emerge onto the political scene. But for now the isolated life he was leading in Busseto with Giuseppina suited him, even if it meant deprivations for her and tensions in relationships that had once meant so much to him.

This change in mood found its way into Verdi’s music too. Luisa Miller was unlike any of his fourteen previous operas. Gone are the big set-piece scenes. This is an altogether more intimate work, but no less dramatic for that. It is drama on a smaller scale.

Two families from different social strata, one in a middle-class home, the other in a castle; two fathers, with different aspirations for their children; these are as close to ‘ordinary’ people as Verdi ever portrayed in an opera. There are no political overtones; it is a drama of individuals, set in scenes of domesticity. There is love, thwarted love, duplicity and death, and for these themes Verdi had found a new style of music.

Rather than simply accompanying the singers, the orchestra plays an independent role, as if it, too, were a character. But he uses fewer musicians, or rather deploys them in a different way. There is a ‘symphonic’ feel to the music, evident from the opening notes of the overture.

It is unlike any overture Verdi had written to date. There is no hint of any of the themes or melodies to come. Instead it is based on rhythms that modulate and intensify. The clarinet has a soaring phrase near the start, and re-emerges at key points in the work, as if it were another singer.

This is a Verdi who has, consciously or subconsciously, moved on. He has entered a new phase, both musically and as a human being. The operas he would embark on next would prove to be his greatest and best loved, and they would owe little, or nothing, to his past works.

Similarly, as a man, Verdi was about to enter a new phase of his life. From now on, he determined to be less beholden to theatre managements. He would be his own man; he would choose his own subjects. This applied to censorship too. I believe Verdi had an innate belief, an understanding even, that censorship would one day end, or at least become so diluted as to be ineffective. If the events of 1848 could take place, who could tell what else might one day follow?

And so for his next opera, almost in defiance, he chose a story that he asked his long-standing librettist Piave to adapt from a French play entitled Le pasteur.

Under the new title, Stiffelio, it included practically everything that could be guaranteed to offend the censor, politics aside. A Protestant pastor, verses from the Bible sung on stage, the depiction of a religious rite, an adulteress portrayed sympathetically by her husband who actually speaks of forgiveness, an altar, pulpit and church benches – and to cap it all, singers dressed in normal everyday clothes. Verdi even included elements of sacred music in his score.

He could not have set his opera up for more of a mauling by the censor if he had tried. And that was what it got. When it had its premiere in Trieste, where it was certainly better received than the last work he had staged there, it had been purged of all religious references and bore little relation to what Verdi had written.

Verdi, giving it up for lost – ‘castrated’ he called it – wrote a new version called Aroldo, and ordered the original Stiffelio to be destroyed. Fortunately for posterity Aroldo swiftly vanished, and Stiffelio – as Verdi wrote it – survived, to be regarded today as a major achievement. It was to prove to be the forerunner of some of his greatest works, containing dramatic elements and contrasting characters that would come to fruition in later works such as Otello and Don Carlos.

For now, though, Verdi retreated once more to the quiet cloistered life in Busseto with Giuseppina. It would not remain quiet for long. He was about to enter a truly turbulent period in his private life. In his professional life, however, his most productive and successful period was about to begin. The galley years were over.

* It is not known whether she saw the boy, now aged eleven, or maintained any personal contact with him.

† Margherita Barezzi’s brother Giovannino, who had always enjoyed a close relationship with Verdi.

‡ When my wife Nula and I visited Busseto in October 2016, we heard this from several people, who were eager to show us those first-oor windows, the shutters still firmly closed.