13

THE OPERA IS ‘REPUGNANT, IMMORAL, OBSCENE’

Even before Stiffelio, Verdi had read a play by Victor Hugo called Le roi s’amuse and thought it might make a strong plot for an opera. In fact, writing to Piave, he described it as ‘the greatest drama of modern times’,60 and urged him to start work on a libretto.

Verdi had been approached by La Fenice, the Venice opera house (with which he was still on good terms) to provide a new opera for the forthcoming season. Verdi had accepted, and decided to work once again with Piave, who was chief librettist at La Fenice. That way, Verdi calculated, the path to opening night should be made somewhat smoother. He could not have known how wrong he was.

It is easy to see why Hugo’s story so captivated Verdi. It is packed with drama, difficult relationships, ambiguous characters, a love affair, a curse that hangs over the whole story, and ultimately murder. The most dissolute character, a relentless womaniser and rapist, is a monarch, King Francis I of France. The man who mocks him and comes to despise him is not only a court jester – there is barely a rung on the social ladder low enough for him – but a hunchback too. In other words, Hugo completely subverts convention. Unfortunately for Verdi, what had been accepted in print was deemed scandalous on stage.

When Le roi s’amuse was first staged, it caused outrage in Paris, was banned after just one performance and was not staged again for another fifty years. If Verdi thought that the Austrian censors in control of Italian theatre would be any more lenient, he was to be sorely disabused of the notion.

In fact, he was aware of the potential problem of securing approval for his opera, but considered it easily dealt with. The solution lay with Piave. He was chief librettist at La Fenice; he was on good terms with the management. Verdi instructed him to speak to them and get clearance from them first, which would make the censors’ approval all the easier to obtain. Piave, ever obedient, said he would, and reassured Verdi that from an informal conversation he had already had with one of the management, he did not expect any difficulty.

Piave submitted his libretto to the board of La Fenice. The new title was La maledizione (‘The Curse’), which Piave – perhaps to mollify the board – confessed he did not like, suggesting it could be changed.

Then he settled in to wait for the board’s response, aware that back in Busseto Verdi was waiting somewhat anxiously too. He must have been shocked rigid when the board came back to him, objecting to the libretto on a raft of grounds: the King of France was falsely portrayed, his immoral actions would never have been committed by a divinely appointed monarch, and all in all the story was cruel, violent and immoral.

It was a devastating ruling, appearing to shut the door on the new opera; it was beyond saving. Piave objected as strongly as he was able, to no avail. He passed the bad news on to Verdi.

In a stinging letter to the board of La Fenice, Verdi put the blame entirely on the hapless Piave, stating that on the librettist’s assurance that there would be no problems, he had already done a substantial amount of work on the opera, in fact most of it was already completed. And his letter contained a clear threat: ‘If I now were forced to take on another subject, I would not have enough time to undertake such a study, and I could not write an opera which would satisfy my conscience.’

The board realised they would have to compromise, or they would have no opera. They took a similar step to Piave, misguidedly assuring Verdi that the censor would raise no objections.

The Public Order Office, the censors, reacted even more strongly than the board of La Fenice. The plot of the proposed opera was ‘repugnant’ and ‘immoral’, replete with ‘obscene triviality’. It was so far from being acceptable, wrote the Director of the Public Order Office, that it was not only banned absolutely, but changes of any kind were prohibited.

La maledizione, Verdi’s new opera, was dead in the water. But this time he was not going to take it lying down. He was no longer the Verdi who could be pushed around, who agreed to adapt his creations to satisfy the whim of petty officials with no idea of what constituted art.

He went on the attack. He refused the theatre’s entreaties to rework the opera in the hope that that might make it acceptable to the censors. He wrote to the secretary of the theatre’s board: ‘I tell you particularly, and in a friendly way, that even if they shower me with gold, or throw me in prison, I absolutely cannot set a new libretto.’

Verdi’s frustration is understandable. As is the fact that his usual psychosomatic problems were rearing up to torment him: throat problems, chest problems, stomach problems. ‘Whatever did I do when I accepted that contract?’ he wrote to a friend.

There was deadlock. The censors stood firm. Verdi would not attempt any sort of rewrite. La Fenice was in danger of losing the opening production of its new season. With just two weeks to go, posters and programmes about to be printed, Verdi tore up his contract and La Fenice had no opera.

Fortunately for the history of music, the story was not yet over. Remarkably, of the three protagonists (Verdi, the theatre, the censors) it appears it was the censors who ultimately backed down – one in particular, albeit ever so slightly.

Piave, along with a board member from La Fenice, went to see the most senior of the censors, the Director of Public Order. Between them, a compromise was hammered out. The chief censor allowed the plot to stand in its original form, but the main character could no longer be a monarch. He allowed the jester to remain deformed, but the kidnapping of his daughter would have to be handled in a way that ‘conforms to the demands for [decency] on stage’.

That last demand was suitably vague, the other stipulations not so severe, and Piave thought Verdi might just possibly agree to the changes. He immediately left for Busseto to see Verdi. We can only imagine how relieved Piave must have been to find the composer in a mood that suggested a satisfactory outcome might not be beyond the bounds of possibility.

Better than that, at their very first meeting Verdi agreed that the setting of the story should be changed from the royal court in France to a small independent duchy; the king should now be an anonymous duke whose name would not be revealed; certain other names would change; decency would prevail; and – perhaps most importantly for Verdi – the opera would now be the last of the season, giving him more time to complete it.

In a move obviously calculated to appease Verdi, he alone was allowed to decide on the handling of the crucial denouement, when the jester discovers that the body in the sack is that of his daughter.

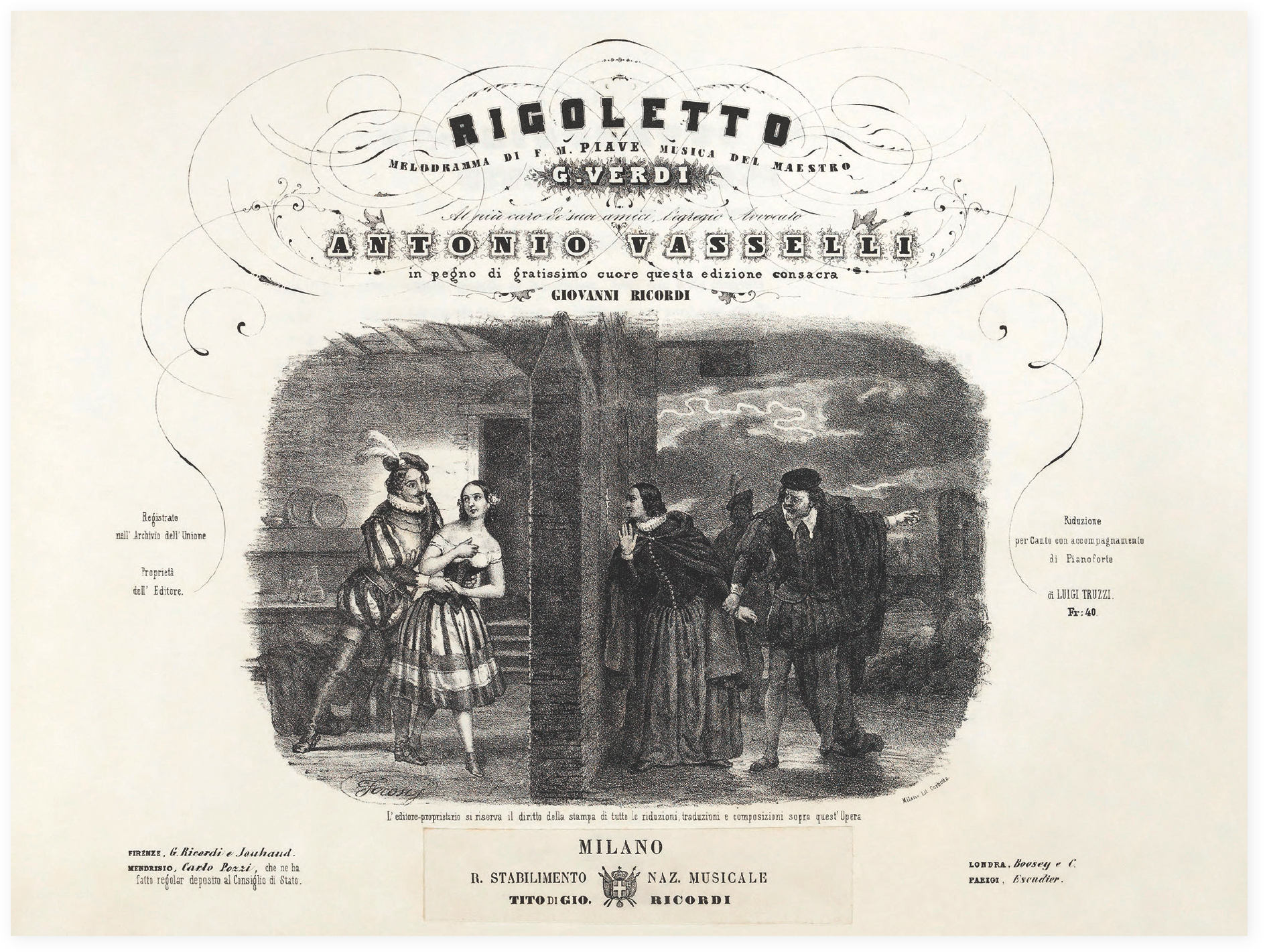

One other change in particular was also made. It is not clear exactly when this was decided, how it came about, or who suggested it. The opera adapted from Le roi s’amuse began life as La maledizione, then became Il duca di Vendôme, and then in a letter to Piave on 14 January 1851 Verdi first used the name of the jester, the name that would prevail, that would secure its place in operatic history as Verdi’s greatest creation to date, one of the best loved he would ever write, and a firm fixture in opera houses around the world to this day and beyond: Rigoletto.

Despite stomach problems, despite a private life that was threatening to spiral out of control (of which more in the next chapter), Verdi worked long and hard hours, setting the words provided by Piave as soon as he received them – words that had been passed by the censor.

On 26 January Piave wrote to Verdi in colourful and excited language:

Dear Verdi, Te Deum laudamus! Gloria in excelsis Deo! Allelujah! Allelujah! At last yesterday at three in the afternoon our Rigoletto reached the directors safe and sound, with no broken bones and no amputations.

Verdi still had the last act to complete and orchestrate. Ten days later, he wrote to Piave: ‘Today I finished the opera.’ It had taken its toll though. Ever suspicious, Verdi feared that the management of La Fenice might now try to bring the performance forward, but he wanted enough time for the singers to learn their parts, and for there to be sufficient rehearsal.

He might have been exaggerating, but probably not by much, when he wrote to the management stating that the sheer effort of completing the opera had left him really ill, and that if they tried to make any scheduling changes whatsoever he would send them doctors’ certificates.

Interestingly, at the same time his business sense did not leave him. He sent a letter to his publisher Ricordi confirming that La Fenice had the right to stage the opera, but only in Venice. The score would be Ricordi’s ‘own, absolute property’, but only on payment of:

… fourteen thousand francs in 700 gold napoleons of 20 francs each … You will have to pay me 300 of the 700 gold napoleons (and not 400) immediately after [Rigoletto] is staged, and you will make this amount available to me at the Poste Restante in Cremona as I return from Venice. You will pay me the rest in monthly payments of 50 napoleons beginning on the first of next April and continuing in the same way on the first of each month until it is paid.

In an era before agents came on the scene, Verdi was more than capable of negotiating for himself!

Verdi arrived in Venice to supervise rehearsals, well aware that after weeks of fraught negotiations, setbacks, unreasonable demands, he was now very much in the driving seat. The season at La Fenice was not going well; audiences were disappointed, and this was reflected in low ticket sales. Piave wrote to Verdi that Rigoletto was awaited as the ‘salvation’ of the season.

Now it was Verdi’s turn to make demands. He got the singers he wanted and the rehearsal time he demanded. Still, with just three weeks until opening night, there was a lot of work to do.

Piave had secured for Verdi the two warmest and sunniest rooms in the city’s finest hotel, the Hotel Europa, and had had a piano installed for Verdi’s use. Now it was down to the hard work of getting the new opera ready for opening night on 11 March 1851.

Verdi himself was in no doubt about the worth of this new opera – why else would he have fought so hard to bring it to fruition in the form he wanted? He was aware that in the original play Victor Hugo had turned convention on its head. Verdi himself, in a letter to Piave, used fine understatement when he described his opera as ‘somewhat revolutionary … and therefore newer, both in its form and style’.

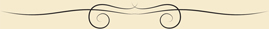

A ruler (even if now a duke rather a king) was the villain, a hunchback jester the hero. The word ‘hero’, though, is too simplistic a description for Rigoletto. He is a father full of love for his daughter, and yet with a thirst for revenge so strong he is prepared to plot murder. Verdi himself said of him, ‘I thought it would be beautiful to portray this extremely deformed and ridiculous character who is inwardly passionate and full of love.’61

The duke, handsome and with an unquenchable desire for seduction – at whatever cost to the woman or her family, or indeed her husband – is portrayed as shallow and immoral. To him Verdi gives the aria that runs through the whole work, and is possibly the most instantly memorable he was ever to write. He banned his singers from whistling it in the street before opening night, because he did not want to spoil the surprise of it. But those (from his day to this) who consider it a fine example of Verdi’s tunefulness, should remember he composed ‘La donna è mobile’ as a pastiche, a piece deliberately designed to be shallow and trivial, to reflect the character of the duke.

Even Sparafucile, the murderer, has a certain dignity. As for the main female part, Gilda, Rigoletto’s daughter, she is torn between love and virtue, allowing herself to be seduced even though she knows the pain it will cause her father. She is thus caught in a dilemma. She must either lie to him, or hurt him beyond measure.

At every point in the opera, the music perfectly captures the sentiment, the conflicts of emotion, duplicity, duality, and moments of utmost tenderness. Gilda’s aria, ‘Caro nome’, is almost as well known as ‘La donna è mobile’; and the duet in which father and daughter remember her mother, now in heaven, is one of the most moving moments in all Verdi opera. And over everything hangs the curse, uttered by Monterone – another father whose daughter has been seduced by the duke.

This was an opera unlike any Verdi had written before. He knew it; so did the audience. The opening night was a total triumph. Some critics, as always, found fault, perhaps unsurprisingly, with the ‘violence’ and ‘licentiousness’, one reporting that the audience left the theatre ‘empty and disgusted at such a horrendous and nauseating spectacle’.

One wonders if he was at the same opera as another critic, who wrote that the

composer was hailed, called out, acclaimed after almost every piece, and two numbers even had to be repeated … it is stupendous, admirable … it cries out to you, it instils passion in you … it strikes you with sweet, ingenious passages. There was never such powerful eloquence in sound.

A plaudit came from an unlikely quarter. The author of the original, Victor Hugo, who had castigated an earlier adaptation by Verdi and Piave of his play Hernani as Ernani in 1844 as ‘a clumsy counterfeit’, now wrote that he regretted his earlier reaction. For particular praise he singled out the Quartet near the start of Act Three of Rigoletto, in which four voices blend with vastly different emotions. It caused Hugo to remark, perspicaciously, that he could only wish there was a way of making four characters express different sentiments simultaneously in spoken drama.*

The opening night presaged an extraordinarily successful early life for Rigoletto. In the same year, it was produced in Rome, Trieste, Verona, Bergamo and Treviso. The following year saw productions in Turin, Florence, Padua, Genoa, Bologna, Parma and its first showing outside Italy at the prestigious Kärtnertortheater in Vienna. Many other Italian cities followed, and it soon began to travel further afield.

By the end of 1853 it had been seen in Corfu and Budapest, as well as in Austria (again), Malta, Germany, Russia, Portugal, Spain, England, Scotland and Poland. It went on to Gibraltar, Alexandria, Bucharest and Constantinople. Rigoletto crossed the Atlantic in 1854, to be seen in New York and San Francisco, as well as in Havana and Montevideo.

Giuseppe Verdi was now world famous, an achievement not lost on his fellow countrymen. If, in the past, he had aroused mixed emotions both professionally and personally, that was now forgotten – at least for the time being. Almost all Italians with even a modicum of interest in the arts were proud of their musical son.

It was well over a decade since Verdi had had an unqualified success on home soil; that had been Macbeth in 1847. But this was on an altogether different scale. Verdi the composer had grown and matured, entering now not just his most productive years, but composing operas of a kind neither Italy nor the world had ever heard or seen before.

With Rigoletto, Verdi eclipsed all who had gone before him. Names such as Bellini, Donizetti, and especially Rossini, were still revered, but Verdi had now unquestionably surpassed them. At the age of just thirty-seven, who could tell what masterpieces might lie in the future?

It was a valid question, and one that Verdi would answer again and again in his long life. Yet with the benefit of hindsight, we can see now that Verdi’s achievement with Rigoletto was all the more remarkable, given the turmoil that beset other aspects of his life.

While he was writing it, while he was castigating Piave with letter after letter, while he was fighting the management of La Fenice and then the censors, his private life – away from all the tensions of trying to create an opera and get it to the stage – was in turmoil.

Amid all the excitement and publicity surrounding the opening night of Rigoletto, the presence of local and regional dignitaries, Verdi’s legion of supporters determined to ensure the opera’s success, one man was missing.

Verdi’s most loyal supporter, the man who was the first to recognise his genius, who nurtured and supported him from the very start, who loved him like a son, Antonio Barezzi, refused to go to Venice to attend the opening night.

Verdi was hurt and confused. But really he should not have been. Barezzi was not alone in distancing himself from Verdi; in fact there were many who now openly shunned him. He might have been hurt and confused, but he could not plead ignorance. He knew exactly what he had done to offend them.

* This remarkable piece of writing was undoubtedly inspired by the Quartet in Act One of Beethoven’s Fidelio, and remains a source of inspiration to this day. A performance of it by four retired operatic singers, and their conflicting emotions, formed the plot of the 1999 play Quartet by Ronald Harwood, and the subsequent film.